AWARFULLOFWONDER

‘ Whohasnotpaidhistributetothesuperstitionsoftrenchlife?’

(BenitoMussolini,November )1

Violentcollectivecrisesgeneratemanyextraordinarypersonaland nationalexperiencesthattranscendbothoursenseofreasonand ourunderstandingoftheboundariesofthepossible.TheFirstWorld Warwasnoexception.Itwasconsideredatthetimeasauniqueportal intotheoccultorhiddenaspectofthehumancondition,amoment whenthespiritualandthepsychicalfateofhumanitywasinthe balance.Supernaturalvisions,suchasthenotoriousappearancesof ghostlymedievalarchersattheBattleofMonsin ,werereported anddebatedinawayneverbeforeexperiencedinnationalpubliclife. Churches,occultists,andpsychicalresearchersacrossthewarringcountriessawopportunitiestoextendtheirhorizonsandinfluence,whilethe publicreachedfortraditionalandnovelwaysofcopingwiththerealities ofwarfare.Pursuingthesupernaturalthreadsacrossthecombatant countriesrevealsthatmagic,religion,andsciencewerecomfortable companionsinthecrucibleofmodernitythatwastheFirstWorldWar.

TheFirstWorldWarhasbeendescribedasthe firstscienti ficconflict intermsofboththeinnovative,technologicaldevelopmentsthatwere embracedbythemilitaryandthenewadvancesinmedicine,engineering,physics,andchemistrythatwereinspiredbythewareffortacross thecombatantcountries.ButtheemergentsocialsciencesinAmerica andcontinentalEuropealsosawthewarasauniqueopportunityto furtherscholarlyunderstandingofbehaviouraltraitsandbeliefs,and, ultimately,torevealtheessenceofwhatitmeanttobehuman.The battlefieldsofFranceandBelgiumwereconsideredauniquelaboratory forsociological,psychological,andanthropologicalresearch.Whatbetter environmenttostudytheextremesofphysicalandmentalendurance,to

testtheeffectsofstressandthesymptomsoftraumaaspeoplefaced mechanizedmasswarfareforthe firsttime?Theworkonshellshock isthemostwell-knownoutcomeofthisacademicinterest.Butthere wereotherareasofsocialscienceresearchthathavereceivedmuch lessattention.

PsychologywasestablishedasanacademicsubjectinGermanyin the s.TheFirstWorldWarpresentedtheyouthfuldisciplinewith unprecedentedopportunitiestofurthercementitselfinuniversities, toproveitsvaluetonationalinterests,and,morespeci fically,tothe military-industrialcomplex.Germanpsychologistswereactive,for example,indevisingandemployingaptitudetestsforemployeesand themilitary,andforassessingcombatmotivation.Appliedpsychologist andfrontlineof fi cerPaulPlautusedhisobservationsinthe fi eld,as wellasaquestionnairedisseminatedatthebeginningofthewar,to constructatheoryofpsychiccrisis,whichhesawasmanifestingitself inavarietyofways,including ‘ superstitious ’ observancesandrituals. 2 But,duringthewar,andinpartthankstoit,Americaovertook Germanyasthepowerhouseofpsychologicalresearch.Duringthe s,onethirdofallpsychologypapersintheworldwerewrittenby Americanscholarsandprofessionals. 3 UntilAmericaenteredthewar inApril ,Americanpsychologistscouldclaimtobeperfectly placedtomakeadispassionate,unbiasedassessmentofthemental consequencesofthecon fl ictamongstmilitarypersonnelandonthe homefronts.In ,forinstance,GeorgeWashingtonCrilewroteof howhejumpedatthechancetotakechargeofaunitoftheAmerican AmbulanceinFrance.Hediditforcompassionatereasons,butalsoto furtherhisresearchonthephysicalconsequencesofcombat ‘when underthein fl uenceofthestrongestemotionalandphysicalstress ’ , andspeci fi callytostudytheeffectsofinsomniaandextremefatigue insoldiers.4

Americanpsychologistshadalsopioneeredthescienti ficstudyof contemporarysuperstitionasanestablishedacademic field.In ,the educationalpsychologistFletcherBascomDresslarpublishedahuge surveyofsuperstitiousbeliefsamong schoolstudents,withthe purposeofpeeping ‘intothatdarklyveiledbutinterestingmental realmwhichholdsthebestpreservedremnantsofourpsychicevolution,aswellasthoseethnicimpulseswhichareresponsibleformuchof ourpresentbehaviour’ . 5 Othersconductedsimilarstudiesduringthe

waryears,includingafour-yearsurveyofthesuperstitiousbeliefsof first-yearpsychologystudentsattheUniversityofOregonbetween and . 6 Althoughsuchresearchwasnotextendedtothemilitary inthisperiod,Americanpsychologistswerealivetothestoriesof visionsandspiritualistseancesemanatingfromBritainandFrance, andtheywereintriguedbytheirsigni ficance.In ,thepioneering Americanchildpsychologist,eugenicist,and firstpresidentofthe AmericanPsychologicalAssociation,GranvilleStanleyHall,wrotein his ‘PsychologicalNotesontheWar’ that,asastrikinginstanceofcredulity,theAngelsofMonsreportswereofgreatinteresttothepsychologist asanexpressionofstressandanxietyinwartime. ‘Nowarwaseverso hardonthenerves,’ heobserved.7 AneditorialintheAmerican Journalof EducationalPsychology inMay opinedthatduetotheheightened religiousfeeling,generalgloom,andbereavement, ‘Aparticularlysinister formoftheweaknessofcredulityseemstobeontheincreaseamongthe intellectualsofEnglandandFranceintheacceptanceofevidenceof spiritisticmanifestations.’ Itsuggestedthatthe floodofliteratureon spiritualismandpsychicphenomenawouldhaveapernicious,lasting psychologicaleffectonthe ‘uncriticalmasses’ inbothcountries.8

Thepublicbuild-uptowar,andlifeunderwarconditions,were exploredasanaspectofcrowdbehaviourbytheBritishsocialpsychologistWilfredTrotterandothers.Inhissuccessfulbook, Instinctsofthe HerdinPeaceandWar ( ),hedescribedGermanyasa ‘perfectaggressiveherd’ characterizedbythewolf,andBritainasa ‘socialised’ herd modelledonbeebehaviour.9 Psychologistsandsociologistswerealso interestedinthenatureandinfluenceofrumoursandfalsenewsthat disseminatedacrossthecombatantpopulations,andwhichexposed, likesuperstition,thesameveinofwhattheyconsideredmasscredulityin wartime.Whatwecallfakeandviralnewstodaywereissuesacentury ago.Therewerenumerousspypanics,falsereportsofGermanatrocities inBelgium,andrumoursofZeppelinraidsalongtheAmericancoast,to namebutafewexamples.Russiansweresaidtohavedisembarkedin theirtensofthousandsinScottishports.NewsoftheKaiser’sdeathor suicidecirculatedperiodically.GermansevenheardstoriesofanearthquakeinLondon.10 Fromearlyoninthewar,LucienGraux,whoserved asamedicaldoctoratthefrontandbehindthelines,decidedtocompile alltherumoursandfalsenewshecould find,somedirectlyfromsoldiers, butmostcollectedsecond-handfromnewspapersandotherprinted

literature.Hismotivationwastoexplorethepsychologyofoptimismand pessimisminwartime.Thisresultedinahugemultivolumepublication ofmaterialpublishedin . 11 Thesamestoriesalsofascinatedfellow FrenchmanMarcBloch,whowouldgoontopioneerthehistoryof mentalities.Heenlistedasasergeantintheinfantry,risingtocaptain, andreceivedthe Légiond’honneur forhisbraveryinaction.Hehadamore perceptiveandsophisticatedintellectualperspectivethanGraux,dismissinghisvolumesas ‘alonganthologyofbitsandpieces,borrowedfrom thisorthatsource’.ForBloch,therumoursheheardat firsthandinthe trencheswereafascinatinginsightintothepsychologyofeyewitness accountsandhowlegends,gossip,andrumourwerebornandhow theypropagatedthemselves. ‘Noquestionshouldfascinateanyonewho lovestoreflectonhistorymorethanthese’,hewrotein . 12 Hewas convincedthatmilitarycensorshipandpoorpostalconnectionsledto ‘awonderfulrenewaloforaltradition’ inthetrenches.Blochfelthislife atthefrontwaslikelivingthehistoryofapreliterateage,and,assuch, providedauniqueopportunitytolearnhistoricallessonsaboutan otherwiselostworldofpopularculture.Inreality,andwithhindsight, theroleofprintwasessentialtothespreadofrumourandtraditioninthe trenches,withsoldiers’ home-madenewspapersactingasonemedium forthespreadofgossip,songs,legends,andhumour.13

‘Thesuperstitiousritesthatcameoutofthewarorwererevivedbyit deserveaseparatestudy,’ saidBloch. ‘Mr.Dauzatgivesthemanimportant place.’ HewasreferringtotheFrenchlinguistandfolkloristAlbert Dauzat,who,in ,publishedasocial-psychologicalstudyofrumours, legends,prophecies,andsuperstitionsgeneratedbythewar.14 Itwasthe firstand,untilrecently,onlycomprehensivestudyofFirstWorldWar supernaturalbeliefs,primarilyamongtheFrenchbutalsowithreference torelatedmaterialfromBritish,Swiss,andGermannewspapersand research.ForDauzat,likethepsychologists,visions,apparitions,prophecies,andthewearingofamuletswereallonthesamespectrumof credulity,andrepresentedancientfearsandsuperstitionsthatwere exhibitedtoagreaterorlesserdegreebystressonweakoremotivebrains. Butbeyondthephysiologicalandpsychological,folkloristslikeDauzat werealsointrinsicallyinterestedinthebeliefsexpressedandtheirdeeper culturalmeaning.

SomeEuropeananthropologistsandfolklorists(thetwodisciplines intertwinedattimes)alsosawthewarasauniquelaboratory.Fromthe

beginningofthefolkloremovement,whichemergedacrossEurope inthemid-nineteenthcentury,thecollectionofsuperstitiousideas amongsttheruralpopulationhadbeenoneofthekeyactivitiesof itspractitioners.By ,therewasnoshortageofevidenceforthe continuedwidespreadbeliefinmagic,witchcraft,omens,andghosts. Whiletheirinterestsinfolklore,or Volkskunde inGerman,overlapped withthepsychologists,andtheycouldbenolesscondescendingintheir referencestothesupernaturalattimes,folkloristsconsideredsuperstitionsindifferentwaysandcontexts,andstudiedthemfordifferent purposes.OttoMauser,theGermandirectoroftheBavariandictionary archive,wroteenthusiasticallyin , ‘Amongallthehumanities,however,thetaskofpersonallyobservingandcollectingthemanifold manifestationsofthewarfallsto Volkskunde. ’15 Superstitionswerecollectedalongwithfolksongs,legends,religiousobservances,slang,and materialculturetoexplorethetransmissionandcommunicationof ideas,beliefs,andexpressionsamongstmenthrowntogetherbywar andforcedtoliveinunusualintimacyunderextraordinaryconditions. Italianfolklorists,forinstance,wereparticularlyinterestedintheculturalexchangesbetweensoldiersfromverydifferentregionsofItaly. Prisonerofwarcampsprovidedanotherlaboratoryforfolkloristsand physicalanthropologiststoexamineEuropeanethnictraits(littleinterest waspaid,however,tothemillionsofnon-Europeancolonialsoldiers).

Atthetime,therewasastrongimpulseinfolkloreandanthropologicalstudiestorecoverandcollect likearchaeologistsofthe intangible beliefs,practices,andtraditionsthatwereconsideredsurvivalsfromtheearlystagesofhumansociety,mentalfossilsfroma prehistoricage.Tribesacrosstheglobewerethoughttobestillstuckin thisearlyphaseof ‘primitive’ magicandtotemicreligiousworship, whileinEuropeonlyfragmentsofthisdistantworldremainedamong theuneducatedpoor,orlaylongdormantinthewiderpopulation.The conditionscreatedbythewarwerethoughttohavereawakenedthese ‘primitive’ tendenciesortohaveshakenthemtothesurface.Armchair scholarsscouredthepressforevidence,butsomewereoutinthe field apparentlyglimpsingthetraitsofthiselementarypastat firsthand.The AmericananthropologistRalphLinton,forinstance,drewuponhis ownfront-lineexperienceinFrance, fightingwiththe nd ‘Rainbow’ DivisionoftheAmericanExpeditionaryForce(AEF),inexploringthe creationofprimitive,totemisticbehaviourin ‘modern’ societies.He

noticedthewaygroupsofsoldiersgeneratedtheirownunofficial insigniaandsetofobservances,andalsoadoptedmascots.Inone instance,a ‘subnormalhysteric’ wasconsideredtobegiftedwithprescience,andtheenlistedmeninhisgrouprelievedhimofregular dutiessolongasheforecasttheoutcomeofexpectedattacks.He comparedthisobservedbehaviourwithrecentstudiesofthetotemism ofAustralianaborigines,Melanesians,andnativeNorthAmericantribal groups,concludingthattheAEFcomplexesand ‘primitive’ totemism bothresultedfrom ‘thesamesocialandsupernaturalisttendencies’ . 16

Swissfolkloristswerethepioneersindevelopinganew fieldof Kriegsvolkskunde orwarfolklore.Althoughthecountrywasneutral,it mobilizeditsarmyatthetimeandsetupPOWcamps.Itwasfarfrom beingdetachedfromtheconcernsandimperativesofthewarring French,Italians,Austrians,andGermansonitsborders.In the SwissSocietyfor Volkskunde,foundedin byEduardHoffmannKrayer,gainedthesupportoftheSwissmilitarytodistributeaGerman questionnaireviathevenerablejournalofmilitarystrategyandpolitics, the RevueMilitaireSuisse,aswellasinSwissmagazines.Itwasalso disseminatedinFrenchperiodicalsandtranslatedintoItalian.ItconsistedofthirteenthemesorquestionsaddressedtoSwisssoldierswho camefromamixoflinguisticandethnicbackgrounds.Thesurvey includedquestionsaboutthewaysinwhichtheyprotectedtheirlives. Didtheypossessmedals,blesseditems,amulets,magicalobjects, andthelike?Whatpopularremedieswereemployedbysoldiers? Whatomenspredictedwar? 17 Theprojectwasdevisedprincipally byHoffmann-KrayerandGerman-Sw issfolkloristHannsBächtoldStäubli,whowasemployedasamilitarycensorduringthewar.The datagatheredresultedinaseries ofsmallpublicationsandfedinto themonumental HandwörterbuchdesdeutschenAberglaubens (Handbook ofGermanSuperstitions),whichwaseditedbyHoffmann-Krayerand Bächtold-Stäubli,andpublishedafterthewar.18

TheSwissprojectactedasaresearchnexusacrossthewarring countries.Bächtold-Stäublikeptupapersonalcorrespondencewith Dauzatabouttheir findings,andtheSwissinitiativemotivatedthelatter tolaunchhisownquestionnaireonFrenchsoldiers’ jargon.Italsogave impetustoGermanandAustro-Hungarianfolklorists,inspiringboth individualsandthecreationofnumerousnewlocalfolkloreclubsand associations.Mostfocusedonfolksong,music,folkart,andtrench

slang,ratherthansuperstition.19 Thesewerepopulartopicsforthe enthusiasticItalianresearchersof folklorediguerra,butseveralItalian folkloristsalsocreatedimportantcollectionsofloreandmaterialcultureregardingtrenchreligionandpopularmagic.20 Themostinfluential wasthepsychologistandarmychaplainAgostinoGemelli(–), whowasasmuchmotivatedbyclericalconcernsasscholarlyinsight. Forhim,thesuperstitionsandsongsofthefrontprovidedthefreshest insightinto ‘thesimplesoulofoursoldier’.Buthisresearchexposed whatheconsideredprimitiveandinferiorbeliefsthatneededtobe counteredby ‘true’ faith.Tothisend,heinstigatedareligiousrevival campaignamongstthetroopsinhospitalsandinthecombatzone, distributingtriangularpiecesofclothtobewornonthechestbearing themotto Inhocsignovinces (‘Inthissignyouwillconquer’)andthe words protezionedelsoldato (‘protectionofthesoldier’).21

OneofGemelli’sarch-criticsatthetimewasRaffaeleCorso(–), whoattackedbothGemelli’sandDauzat’ssocial-psychologicalapproaches,and,mostsignificantly,theprevalentviewthatthetheatreofwarhad createdauniquestagefornewandrecrudescentsuperstitions.Corso ’ s viewwasthatthepopularmagicandprotectivetraditionspractised bythesoldiersweremerelyanexpressionofthewider,pervasive superstitionsoftheItalianpeasantryatthetime, ‘ transportedbythe wartimeair,spreadfromlifeinthe fi eldstothatinthebattle fi elds, whereitseemedtoseedand fl ower,almostasarebirth’ . 22 Therewas nouniquelaboratory.Corsosawpopularmagicalbeliefsaspervasive amongstthepooranduneducated,andanexpressionofprimitive prejudice.Thisderogatoryviewofpopularbeliefaside,Corsowasone ofthefewscholarswhoputtwoandtwotogether,weighinguptherich evidenceforthepervasivepopularadherencetopopularmagicacrossthe countrywiththeevidencebeingrecordedinthetrenches,andconcluded, basically,that ‘warfolklore’ wassimplyfolklore.

Fromplentifulwellsofwartimefolklorewemovetodroughtconditions.WhenDauzat,writingin ,surveyedthecontemporaryscholarlyliteratureonwartimebeliefs,legends,andfolklore,hereferenced theItalians,Swiss,French,andGermans,butwhenitcametoBritainall hehadtosaywas, ‘nothingtoreport’ . 23 Hewasright.Scourthepagesof thejournaloftheFolkloreSocietyforthewaryearsandtherearevery fewreferencestotheconflict.Theannualaddressesbyitspresident, RobertRanulphMarett,whohadestablishedaDepartmentofSocial

AnthropologyatOxfordin ,includedwarthemeswithoutexploringthefolkloristicaspectsofwartimebehaviourorbelief.Inhis address ‘WarandSavagery’ ,publishedinMarch ,hetoldhis audiencethattheywere ‘hardlyinamoodforanyscienti ficoccupation. Ourthoughtsare fixedupontheWar,’ beforeprovidingaglobalcrossculturaloverviewofthemeaningofsavagery. 24 Subsequentaddresses onlytouchedtangentiallyonwarmattersordidsoinabstractphilosophicalterms.Inhis fi naladdressbeforetheendofthewarhereferred brie fl ytothosecollecting ‘thesuperstitionsresuscitatedamongall classesbythewar’,beforesuggestingintriguinglythat ‘ thenationcan affordtorecapturesomethingofitsprimitiveinnocence’ . 25 Turntothe mainorgansofacademicanthropologyatthetime,suchastheBritish AssociationfortheAdvancementofScience,andtheRoyalAnthropologicalInstituteanditsjournals,andthewarlikewiseappearsadistant interest,withlittlescholarlypotential.Afewphysicalanthropologists appliedtheirdisciplinetowarmattersinordertoassesstheethnicbasis forthecon fl ict,andtheracialdifferencesbetweentheBritishandthe Teutonicfoe. 26

TheonlysubstantivewarfolkloregoingoninBritainwasconducted byaCityofLondonbankcashier,amuletcollector,andamateur folklorist,EdwardLovett( –).Hisnumerouscollectingtripsto thedocks,markets,andbackstreetsofeastLondonduringthewar provedjustasrichashisfolklorecollectinginthecountrysidearound hishomeinCroydonandthesoutherncounties.InDecember ,he gavealectureattheHornimanMuseuminsouthLondonentitled ‘The InfluenceoftheWaronSuperstition’,inwhichhetalkedaboutsomeof thecharmsandmascotshehadcollected,describingtheirpopularity inwartimeas ‘aretrogrademovementoftwohundredyears’ 27 Later,in theonlybookdedicatedtourbanfolkloreatthetime, MagicinModern London (),Lovettwroteofhisnumerouscasualencounterswith soldiersonthehomefrontduringthewar,whichprovidednewinsights andinformation.Onavisittothesouthcoast,forinstance, ‘therewere twoconvalescentsoldierssittingdown,soImadeanexcusebyaskinga questionandthensatdownnearthemofferingeachacigarette’.Hethen begantoaskthemaboutcharmsandtalismans.Onanotheroccasion, hewaswaitingforatrainatEastCroydonstationwhenhespotteda friendwhohadbeenatthefrontandinvalidedhome.Theybeganto chat,andinhisusualfashion,Lovettsaid, ‘Oh,bytheway,Iamcollecting

notesontheamuletsandmascotscarriedbyourchaps.Iwishyou wouldgivemeoneortwoscrapsofinformationifyoucan.’ Then,one day,whenhewasontheLondonUndergroundgoingfromMonument toFarringdon,hestruckupaconversationwitha ‘Colonialsoldier’ who seemedlost.Anotheropportunityarose.Lovetthelpedhimwithdirections,andthen,seeingashewasgoingtothefront,askedwhetherhe carriedacharmormascotwithhim.28 Therewerenosystematicsurveys, questionnaires,orpsychologicaltheorizing.ButLovett’scasualand humanapproachtofolklorecollectingproducedsomeofthemost valuableglimpsesintothepersonalmeaningofmascotsandcharms thatwehave.

InBritain,theSocietyforPsychicalResearch(SPR)wastheonly organizationofscholarsandresearchersconductingresearchintothe supernaturalaspectsofthewar.SimilarbodiesinFranceandGermany didlikewise.Foundedin ,theSPRmembersweredescribedin The Times in as ‘allsortsofscholarlymen somephilosophers,some clergymen,somepoliticians,andmenofscience’ . 29 Whilesomeofits high-pro filemembers,suchasthephysicistOliverLodge,whowasits presidentbetween and ,andArthurConanDoyle,became ardentadvocatesofspiritualism,otherleading figuresinthesociety,like FrankPodmore( – ),remaineddeeplyscepticalandconsidered mostmediumstobedownrightfrauds.Podmoreandothers,including ConanDoyle,expendedmuchtimeandenergyinsteadoninvestigating hauntingsandpeople’stelepathichallucinationsofthedead.Both agreedfromtheirinvestigationsthattherewassolidevidencethat telepathyexisted,and,asweshallsee,furtherevidencewassought fromsoldiersandtheirrelativesduring –.Otheraspectsofthe occultandthewarwerealsoexaminedbymembersofthesociety.In ,havingjustsurveyedarangeofpropheciespublishedsincethe outbreakofthewar,German-bornOxfordUniversityphilosopher FerdinandCanningSchillerobserved, ‘ourSocietyexistsfortheexpress purposeofrakingovertherubbish-heapsoforthodoxscience,and mustnotshrinkfromthesearchfortruthinunlikelyplaces’.He concludedtherewasnonetobefoundinthewarprophecies,though. ‘Asamatteroffact,itmustbeconfessedthattheevidencewassobad thatitdidnotseemtowarrantfurtherinvestigation.Thebulkofitisjust irresponsible,unauthenticated,unveri fiable,andoftenanonymous, hearsay.’30 Wewillrevisitthisconclusionshortly.

In thecelebratedFrenchfounderofsociology,ÉmileDurkheim (– ),wroteacheaptractanalysingtheGermanmentalattitude towardstheconflict.Itwascleartohimthatthewarwasaresultof Germansocialpathology,anational ‘willmania’ . ‘ Tojustifyherlustfor sovereignty,shenaturallyclaimedeverykindofsuperiority;andthen, toexplainthisuniversalsuperiorityshesoughtforitscausesinrace,in history,andinlegend.’‘Thus’,heconcluded, ‘wasbornthatmultiform Pan-Germanmythology,nowpoeticalandnowscientific. ’31 Durkheim wasoneofnumeroushigh-profileacademicsandwriterswhowillingly turnedtheirhandtowritingsuchanti-Germanpropaganda,solicited andendorsedbytheirrespectivegovernments.Thenewsocialsciences werewellplacedtoprovidesuch ‘authoritative’ opinionontheracial inferiorityandthepathologicalegotismoftheenemy,andtheaccusationofbeing ‘superstitious’ wasbandiedaboutbybothsidesinthe conflictasausefulshorthandtocharacterizethenationalweaknessand moralregressionoftheirpopulations.

Thenewspaperssometimestooktheirleadfromtheacademics,and theacademicssometimestooktheirleadfromthenewspapers.The latterwerefullofstoriesaboutthefoolishsuperstitionsoftheenemy. NumerousreportsappearedintheAlliedpressearlyoninthewar regalingreaderswithexamplesofthecredulousnatureoftheKaiser. So,inNovember ,aBelgiannewspaperstatedthattheKaiser ‘believesintheevileye,intheillluckattachedtothenumberthirteen, &c.Personswhohavevisitedhisstudyknowthatitcontainsacomplete collectionofworksonchiromancyandtheoccultsciences.Allthe propheciestroublehim.’32 The SunderlandDailyEcho reportedinOctober

: ‘Superstitionsakintothosewhichhavebeenobsoleteamong theBritishpeasantryfornearlyacenturyareatthisdayrifeamong theuniformedsonsof “Kultur”.ThereishardlyaGermansoldierinthe rankswhodoesnotcarrysomesortofcharm.’ Theexamplesitrelated includedTyroleanAustriansoldierswhoworebats’ wingssewninto theirunderclothing.33 TheGermanandAustro-Hungarianpresscontainedsimilarpropagandistreports.

Whilenotinghowthepsychologicalstrainofthewarwasboundto leadtoarecrudescenceofprimitivebeliefs,FerdinandSchillerobserved thatitwas ‘justasnaturalthatthealliesshouldcirculatestoriesof supernaturalinterventionsonbehalfoftheirjustcauseasthatthe Germansshouldreverttothemagicalpracticeofhammeringnails

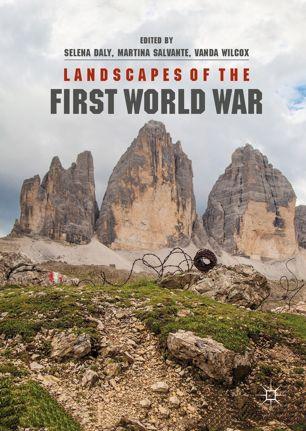

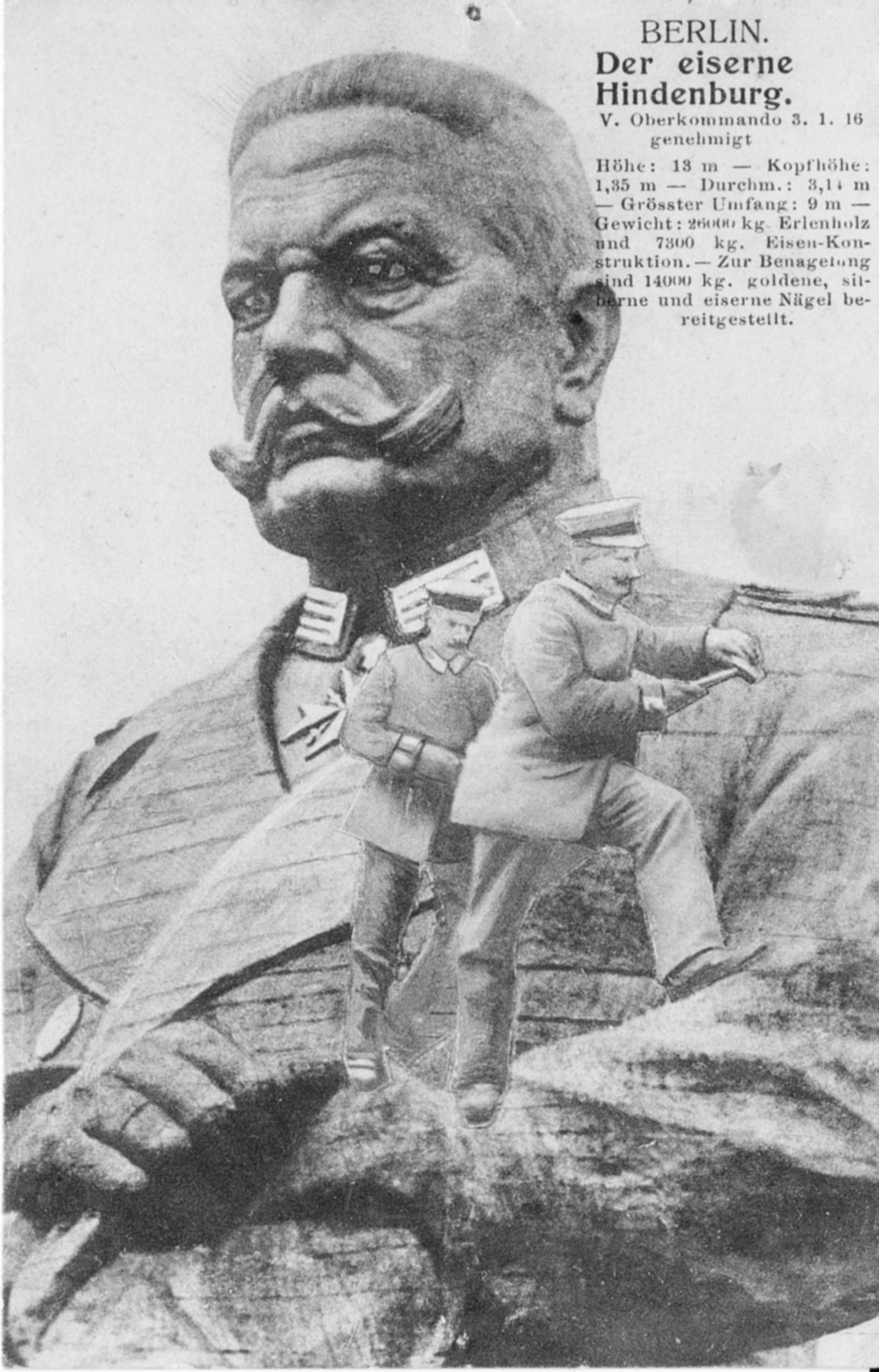

intoimages’ . 34 Theword ‘revert’ wasallimportantinthisstatement.He wasreferringtotheevocativeandprovocativeacademicaccusationthat theGermanauthoritieswereinspiringre-emergentheathenism,and promotingsuperstition,bycreating Nagelfiguren ornailstatues.Between and ,hundredsofwoodenmonumentsrepresentinggreat Germanheroes,suchasCharlemagne,aswellaseagles,lions,crosses, submarines,andthelike,appearedinpublicplacesintownsandvillages acrossthecountry.Citizensandsoldierswereinvitedtopurchasenails ofiron,silver,andgold,eachattractingadifferentprice,whichthey hammeredintothewoodenobjects.Thepracticewasapublicritualof patriotic,collectivesupportforthewar,withthefundsraisedgoingto goodcausessuchaswarwidows,orphans,disabledsoldiers,andthe RedCross.Themostspectacularofthese Nagelfigur wasa -metre-high woodenstatueofGeneralPaulvonHindenburg(–).Itwas erectedinBerlinwithaplatformarounditsothatthepubliccould hammernailsupthetorso.35

InOctober theFrenchnewspaper LeTemps printedanarticleon theoriginofthewoodenHindenburg,basedontheviewsofSwedish ethnographerNilsEdvardHammarstedt.Heconsideredthisvoguefor nailstatuesacontemporarymanifestationofthebasichumanurgeto propitiatethegodsbymakingofferings.Orperhapsitwasaprimalact ofmagic,thepeoplepurchasingandhammeringthenailssecretly wishingtogainsupernaturalfavours.Thenewspaperbelievedthat Hammarstedthadnottrulygraspedthesinisterimportanceandgravity oftheGerman Nagelfiguren,though: ‘Theerectionofthewoodenstatue, the fixingofthenails,constitutesstrangesurvivalsofidolatry,’ thought thepaper.36 Theissuewastakenupinthepagesofthehighlyrespected journal L’Anthropologie in .Inonearticle,theleadingFrenchanthropologistRenéVerneau(

)comparedthewoodenHindenburg withthefetishpracticesoftheLoangoofwhatisnowwesternGabon. Whileitwaseasytopushthecomparisontoofar,heacknowledged,he believedtherewerefundamentalsimilaritieswiththeAfricanreligious practiceofdrivingnailsintowoodenfetish figurines.TheGermanstate wasaccusedofcynicallyreinstitutingancientculticpracticesamongst itspopulation.Herecognizedthatsomeofthosewhostucknailsinthe fetishessawtheiractionsasnothingmorethanapatrioticamusement. Buthewasconcernedthatthe ‘naïve’ whomadepilgrimagetothe statuesweremotivedbymoretroublingappealstosupernaturalaidas

Fig. .. The -metrehigh Nagelfigur orwoodennailstatueofGeneralPaulvon Hindenburg,erectedinBerlin.Thepublicpurchasednailstohammerintoitfor charity.

theyhammeredintheirnails,foolishlyprayingtotheGermanidolin thehopeofachievingtheirdesires. ‘Ourenemiesimpedethetriumphof civilization,’ heconcluded.37 SwissarchaeologistandfolkloristWaldemarDeonnarespondedwithamorenuancedperspectiveonthenailing ofeffigiesandtrees,notingsimilarrecentfolkritualsinthepopular religiouspracticesofallthewarringcountries.Heconcluded,nevertheless,thatthe Nagelfiguren of and wereanechoofancienttree worship,andwere ‘thecontinuationinthetwentiethcenturyofveryold superstitions,therenewalofwhichhasbeenpromotedbythewar, reinforcingthemysticalandcredulousaspectsofthewarringparties’ . 38

Thisoverviewofhowthewarstimulatedintellectualinterestinthe ‘superstitious’ highlightsthechallengesfacingthehistorianinuncoveringandinterpretingthesupernaturalaspectsoftheconflict.Howdowe cutthroughtheearlyacademicassumptions,thepropaganda,themythmaking,andthecondescensiontowardstheuneducated?Tobeginwith, fromthispointonward,Iwillavoidtheterm ‘superstition’,which pervadestheliteratureoftheperiod,andcontinuestobeuseduncriticallybypsychologists.Whencited,itwillbeplacedbetweeninverted commastomarkthatitisusedinrelationtotheopinionofothers. Historiansofwitchcraftandmagichavebeensensitivetothisfora while,awareofhow,inboththepastandthepresent, ‘superstition’ has beenwidelyappliedtodenoteirrational,ignorant,orfallaciousbeliefs andpractices.FollowingtheReformation,itwasusedbyProtestant theologianstodenounceCatholicritualsandtheology.39 Becauseitis suchaloadedterm,weneedtoplaceitincontext,andbeawareofhow itwasunderstoodandusedinthepast.Idonotholdtheviewthatthe beliefsandpracticesexploredinthisbookareinanywaysymptomatic ofbackwardnessorcredulity.Indeed,asweshallsee,thosewhocarried charmsforprotection,performedritualsforgoodluck,wenttofortune tellers,orclaimedtoseeghostswereoftenwell-educated,thoughtful peoplewhowereself-analyticalaboutwhattheydidandexperienced: theywereanythingbut ‘superstitious’ .

Therearearangeofvaluablesources,otherthanthescholarlystudies oftheera,thatilluminatethewiderculturesofbeliefinwartime.The newspaperswerefarfromsupinetoolsofpropaganda,andtheyoften castareflectiveandcriticaleyeontheunorthodoxbeliefsandpractices oftheirowncountries,reportingapparentsupernaturalinstancesor

thepopularresorttomagicwhichdidnotcastapatrioticlighton nationalfortitudeandconfidence.Personalletterstoandfromthe frontcanprovideuniqueinsightsaswell.ButashistoriansoftheFirst WorldWarhavelongdebated,theybringtheirownchallenges,suchas thein fluenceofthemilitarycensorsonwhatsoldiersandsailorschose towriteandhowtheyexpressedthemselves.Whatdidtheyconceal fromtheirlovedonesabouttheirfears,imaginings,andrituals?Thereis alsothematteroflettersdestroyedduringandafterthewarforpersonal orfamilyreasons.40 Battlefieldmemoirsalsocameintotheirownasa literarygenre.Somewerewrittenduringtheconflict,andmanyinthe decadesafter.Theywererichinpersonalreflection,andthevisceral experienceoftrenchandaerialwarfare,andtheirauthorsweresometimesremarkablyopenabouttheiremotionallives.Someevenpurportedtobethememoirsofthespiritsofthewardeadcommunicated fromtheotherworldviaspiritualistseances.Butsuchpersonalsources thatsurviveconcernonlyaminusculepercentageofFirstWorldWar combatants,ofcourse,andweshouldnotforgetthatmanysoldiers wereunabletowrite.InItaly,literacyrateswerearound percent nationallyin ,butsigni ficantlylowerinruralsouthernpartsofthe country.InRussia,onethirdoftheworkforcelackedbasicliteracy. WhileliteracyrateswerehighinBritain,theyweremuchloweramongst theBritishArmy’smanycolonialtroops.41 Althoughthetrenchesmay nothavebeenthesealedworldoforaltraditiondepictedbyMarcBloch, itisimportanttobeawarethatwhatsurvivesonthewrittenorprinted pagedoesnotnecessarilycapturetherichnessorcomplexityofbattlefieldfolkloreortheintensityofsupernaturalexperiences.

Thousandsoforalhistoryinterviewswithveteranswererecorded onbothsideshalfacenturyormoreaftertheendoftheFirstWorldWar. Whilesomeinterviewersaskedquestionsregardingsoldiers’ religious views,byandlargetheyfocusedoncombatandthephysicalsideof battlefieldlife.Thehumour,boredom,andmundanitiesoftrenchexistenceoftencomethrough,andunbiddenbutbriefreminiscencesabout beliefsandtraditionsoccasionallycropup.JamesGoughCooperofthe RoyalFusiliers,whowasinterviewedin abouthisexperienceofthe WesternFront,recalled,forinstance,sittingonapatchofgrassoneday inalulland findingaspideronhisshoulder.Hewasabouttoswatit awaywhenanothersoldiershoutedathimgruffly, ‘Don’tknockthat spideroffyou****.That’slucky.’ Goughbrushedawaythespider

anyway,and,shortlyafter,ashelllandedkillingallthemenaroundhim, andthemanwhowarnedaboutthespiderwasamongthecasualties.42 But,aswithalloralhistories,weneedtobeconsciousofselective memoryandwhatwasconsideredmoreorlessimportanttodiscuss somanydecadesaftertheevent.Othersourcesbearsilentwitnessto popularwartimementalities.Thematerialculture,intheformof charms,talismans,mascots,andluckypostcards,remindsusofthe valueof ‘things’,andhowthesentimentalattachmenttopersonal itemselidedfeelingsofloveandprotection.Cheap,mass-produced trinketswereforgedintotalismansofgreatpotency,whileholyitems accruedsecularpowerinthefurnaceofbattle.

Piecingtogetherthemyriadfragmentsofthoughts,experiences, reports,reminiscences,images,andobjectsgivesusanimpressionistic butilluminatingpictureofawarredolentwithsupernaturalassociations. Thetasknowistodisentanglewhattheyallmean,andwhytheyare importanttoourunderstandingoflifeduringtheFirstWorldWar.

PROPHETICTIMES

Acriticalstudyoftheprophecieswhichhaveeithercomeintobeing orhavetakenupanewleaseofinterestandimportanceowingtothe GreatWarisnoimprobableundertakingwhenthewaritselfshallbe over,anditmightprovideacuriouskindofinstructionaswellas someentertainment.

(OccultistArthurEdwardWaite,writingin )1

TheadventoftheFirstWorldWarwashardlyasurprise.Asthe BelgianpoetandessayistMauriceMaeterlinckobservedin , ‘True,itwasmoreorlessforeseenbyourreason;butourreasonhardly believedinit.’2 NumerousbooksandarticleswerewritteninBritainand Franceduringthelatenineteenthandearlytwentiethcenturiesdebating theinevitabilityofagreatwarinEurope.Therehadalsobeenperiodic spyandinvasionscaresinBritainwithregardtorumoursofFrench, Russian,andGermanattacks.Popularfearswerefedbytheburgeoning genresof ‘invasionlit’ andfuturist fiction,and,bytheearlyyearsofthe twentiethcentury,Germanyhadbecomethepredominantthreatin suchstories,asthe firsttremorsofthecomingwarwerebeginningto befelt.3 Somehadclearpoliticalundercurrents.ErskineChilders’sspy novel RiddleoftheSands ( ),concerningthediscoveryandfoilingof GermanplansforinvadingBritain,wascreditedwithhighlighting Britain’spoormilitarypresenceintheNorthSea,incontrastwith Germany’sgrowingnavalpower.WilliamLeQueux’sscaremongering novel TheInvasionof wascommissionedforserializationinthe Daily Mail in forthepurposeofboostingthepaper ’scampaignfor greatermilitaryspending.WithitsaccountofGermanoutragesin townsalongtheeastcoast,itwentontoselloveramillioncopies.4 Suchwar fictionalsoprovedpopularinFrance.Inthelate s,the FrenchofficerandnovelistÉmile-CyprienDriant( –)wrote La Guerrededemain (TheWarofTomorrow),whichdescribedatlengththe

bravederring-doadventuresofFrenchsoldiersinafuturewaragainst Germany,includingastoryofballoonwarfare.Driantwaskilledin actionattheBattleofVerdun.Similar Zukunftskrieg (future-war fiction) provedpopularinGermanyaswell.AugustNiemann’s DerWeltkrieg: DeutscheTräume (TheWorldWar:GermanDreams)( )wasastoryof highpoliticalintrigueandmilitaryprowessasanallianceofGermany, Russia,andFrancewageswaragainstBritain.TheBritishnavyiscrushed attheBattleofFlushing,andtheinvasionbeginsinScotland.

Suchnationalisticstorytellingfosteredareceptivepublicenvironmentforthewaveofpropheticliteraturethatsurgedoverthecombatantcountriesduringtheearlymonthsofthewar,inspiredbyrumour, evangelicaloptimism,astrologicalcalculations,occultzealotry,andthe utterancesofrogues.When,inFebruary ,CharlesOman,whofor the firsttwoyearsofthewarworkedasacensorinWhitehall,gavehis presidentialaddresstotheRoyalHistoricalSocietyonthesubjectof ‘RumourinTimeofWar’,hedescribedthepropheticliteratureofthe warasacuriousrelic,thelastsurvivorof ‘averyancientandprolific race ’.Assuch,henotedthatadozenorsopropheticwarpamphlets fromdifferentcountrieshadbeencollectedbytheNationalWar Museum(latertheImperialWarMuseum),whichhadbeenfounded thepreviousyear.5 Butasweshallnowsee,thedarkyearsofthewar werefarfromtheendtimesforthisvenerable,divinatorytradition. Indeed,theywereseenbysomeastheheraldofaprofoundspiritual enlightenment,apropheticintimationofagloriousnewworldorder. Still,asthenineteenth-centuryAmericanhumouristJamesRussellLowell advised, ‘Don’tneverprophesy unlessyouknow.’

PropheciesOldandNew

ThecompendiouslistofFrenchwarliterature LaLittératuredelaguerre, publishedin ,listedelevenprincipalbookletsofwarprophecies publishedbetween and ,someofwhichcontaineddozensof differentexamples.Theeditoralsoreferredtothethousandsofhandbills containingpropheciesthatcirculatedaroundthecountry.6 Maurice Maeterlinckcountednofewerthaneighty-threepredictionsandprophecies concerningthecomingofthewar.7 InItaly,GiuseppeCiuffacompileda bookofoverahundredwarpropheciesin ,manyofwhichwerethe sameasthoseintheFrenchliterature, buttherewerealsosomedistinctly

Italianones.8 Oldprophecieswererecycledandgivennewmeaning andpopularityinGermanyaswell,particularlyvariationsofaprophetic folktalethathad firstbeenrecordedin ,knownas dieSchlachtam Birkenbaum or ‘theBattleoftheBirchTree’.Itconcernedatimewhenthe worldwouldbegodless.AfrightfulwarwouldbreakoutwithRussia andtheNorthononeside,andFrance,Spain,andItalyontheother.Aprince dressedallinwhitewouldemergeasasaviourafteraterriblebloody battlenearabirchtreeontheborderofWestphalia.WashetheKaiser?9

PropheciesalsoswirledaroundtheconflictintheNearEast.InNovember ,thespiritualistWellesleyTudorPole(– ),whoserved duringthewarasamajorintheRoyalMarineLightInfantry,andthenin theDirectorateofMilitaryIntelligenceintheMiddleEast,surveyedwhat heknewofrelevantpropheciescirculatinginrelationtotheOttoman Empire.OnewasthatwhenaEuropeankingcalledConstantinemarrieda Sophie,thenanewdawnofChristianitywouldbegininConstantinople.

ConstantineIascendedtothethroneofGreecein ,andhiswifewas calledSophie.ThePersianprophetBaha’ u ’llah(–),thefounderofthe Baha’imovementwhobelievedhewaschosenasthe ‘promisedone’ ofauniversalfaith,wasreportedtohavepredictedtheriseofGerman hegemonyandthedownfalloftheFrenchandOttomanempires.The RhinewouldultimatelyrunredwithGermanblood,heapparently foretold,andthentherewouldcome ‘TheMostGreatPeace’.Tudor PolewasapromoteroftheBaha’imovementinBritain,andbelievedthe warwouldrunasBaha’ u ’llahprophesied.10 When,inSeptember , theOttomanarmywasdefeatedattheancientcityofMegiddo,the leaderoftheBaha’imovementatthetime,Abdu’l-Bahá,declaredthat thiswastheArmageddonoftheNewTestamentandwelcomedthe beginningoftheendtimes.11 Suchbiblicalprophecieswillbediscussed inmoredetaillater,butforthemomentletussurveythegalleryofFirst WorldWarprophets,ancientandrecent,realandlegendary,beginning withthemostfamousnon-biblicalprophetofthemall,Nostradamus. ThepropheciesoftheFrenchphysician-astrologerNostradamus ( –)werepublishedinhisownlifetime,andhavebeenreprinted manytimessince.Consistingofhundredsofquatrainswithoddword combinations,strangejargon,andobscurereferencestobattles,disasters,andplagues,thereisnothingobviouslyapplicabletotheFirst WorldWar.Butthatdidnotstopwhathasbeendescribedasthe ‘NostradamianbattlesofWorldWar ’ . 12 Littleattentionwaspaidto

NostradamusinBritain,thoughtheBritishoccultistFredericThurstan turnedtothequatrainstoseewhethertheyprophesiedanythingabout theDardanellescampaignandthefutureruleofConstantinople.The resultswerelessthanclear.TheNostradamianbattleswereprimarily betweenseveralFrenchandGermanesotericistsseekingto findpatriotic causeintheabstrusephrasesofthequatrains.

ThemainproponentontheFrenchsidewasA.Demar-Latour, whosebooklet Nostradamusetlesévenémentsde –,soldfor franc

centimesin .Demar-Latourtranslatedthequatrainsintomodern Frenchandthensetaboutunlockingtheirsecretmeaningwithregardto thewar.Onequatrainranasfollows:

Sousl’oppositeclimatBabilonique, Grandeseradesangeffusion; Queterreetmer,air,cielserainique Sectes,faim,regnes,pestes,confusions.

UndertheoppositeclimateofBabylon, Therewillbeagreateffusionofblood; Sogreatindeedthattheearthandthesea,theairandtheskywillseemtobe inrevolt

Therewillbedisorders,famine,diseases,andoverthrowofkingdoms.

AccordingtoDemar-Latour,thedisorderwasthoughttoreferto GermanyandIreland,andthefaminealsoconcernedGermany.His otherrevelationsincludedapparentreferencestotheGermanatrocities inBelgium,theoutcomeoftheBattleoftheMarne,theadventof Germanheavyartillery,thefateofSerbia,andtheinventionofthe submarine thelatterwasdivinedfromareferenceto ‘the fishliving underandabovewater’.AstotheKaiser’sultimatedefeat,Demar-Latour foundsigni ficanceinthisquatrain:

ThegreatcamelwilldrinkthewatersoftheDanubeandoftheRhine, Andhewillnotrepent. ButthesoldiersoftheRhôneandstillmoresothoseoftheLoirewill makehimtremble.

AndneartheAlps,thecock[France]willruinhim.13

OntheGermanside,theastrologerAlbertKniepfunsurprisinglycame tosomeverydifferentconclusions.Hedecipheredonequatrainas