ListofFigures

1.1 ‘TheFayumFragments’,fromH.T.Wharton, Sappho:Memoir,Text, SelectedRenderings,andaLiteralTranslation,3rdedn(London:JohnLane, 1895),p.180.©TheBritishLibraryBoard,11340.aaa.11.24

1.2PhotographofP.Oxy.I7in TheOxyrhynchusPapyri,PartI(1898),Plate II.TheBodleianLibraries,UniversityofOxford,R.TextGR.1-1,facingp.11.32

1.3Sappho,P.Oxy.III424,containingpartofFragment3Lobel-Page,from TheOxyrhynchusPapyri,PartIII(1903),p.71.TheBodleianLibraries, UniversityofOxford,R.TextGr.1-3,p.71.33

2.1ExtractfromHermannDiels, DieFragmentederVorsokratiker (Berlin: Weidmann.,1912),I.77.TheBodleianLibraries,UniversityofOxford, shelfmark,N.i.499a,p.89.61

3.1PlanoftheBritishMuseum,ground floor, c.1905.AntiquaPrint Gallery/AlamyStockPhoto.82

3.2MarblestelefoundatSigeum.2.28m.BritishMuseum(1816,0610.107). ©TheTrusteesoftheBritishMuseum.84

3.3InscribedRomanburialchestintheformofanaltar,dedicatedtoAtimetus. BritishMuseum(1817,0208.2).©TheTrusteesoftheBritishMuseum.88

4.1TheoldElginRoom, c.1920,includingthe ‘Poseidon’ torsowithadjusted plastercast.©TheTrusteesoftheBritishMuseum.121

4.2Torsoofamale figureM(‘Poseidon’),fromtheWestPedimentofthe Parthenon.BritishMuseum(1816,0610.103).©TheTrusteesofthe BritishMuseum.122

4.3TheDuveenGallery,1980s:WikimediaCommons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Duveen_Gallery_(1980s).jpg.123

4.4BernardAshmole’ s ‘HighandOver’:Blackandwhitephotograph.Historic EnglandArchive.125

4.5RodinwithhiscollectionofantiquitiesinMeudon, c.1910.Blackand whitePhotograph.GettyImages/HultonArchive.131

4.6AugusteRodin, Iris,MessengeroftheGods (c.1895).Bronze,82.7cm. MuséeRodin,(S.1068):akg-images/ErichLessing.132

4.7MarblestatuefromtheWestPedimentoftheParthenon, figureN(‘Iris’). 135cm.BritishMuseum(1816,0610.96).©TheTrusteesofthe BritishMuseum.133

4.8Gaudier-Brzeska’ssketchofFiguresLandMfromtheEastPedimentofthe Parthenon.Graphiteonpaper,23 14cm.MuséeNationald’ArtModerne, Paris(AM3376D(23)).Photograph©CentrePompidou,MNAM-CCI, Dist.RMN-GrandPalais/HélèneMauri.137

4.9HeadofahorseinSelene’schariotfromtheeastpedimentanddetail fromsouthmetope.Graphiteonpaper,23 14cm.MuséeNational138 d’ArtModerne,Paris(AM3376D(22)).Photograph©Centre Pompidou,MNAM-CCI,Dist.RMN-GrandPalais/HélèneMauri.

4.10HeadandlegofahorsefromtheParthenonfrieze.Graphiteonpaper, 23 14cm.MuséeNationald’ArtModerne,Paris(AM3376D(41asup)). Photograph©CentrePompidou,MNAM-CCI,Dist.RMN-Grand Palais/HélèneMauri.139

4.11GaudierBrzeska, TorsoI 1914.Marbleonstonebase,252 98 77mm. TateGallery,London,transferredfromtheVictoria&AlbertMuseumin 1983.Photograph:Tate.141

4.12 TorsoIII (c.1913–14),SeravezzaandSicilianmarble,27.3 8.9 8.9cm. ImagecourtesyoftheRuthandElmerWellinMuseumofArt,Hamilton College,ClintonNY(2005.6.1).GiftofElizabethPound,wifeof OmarS.Pound,Classof1951.Photograph:JohnBentham.142

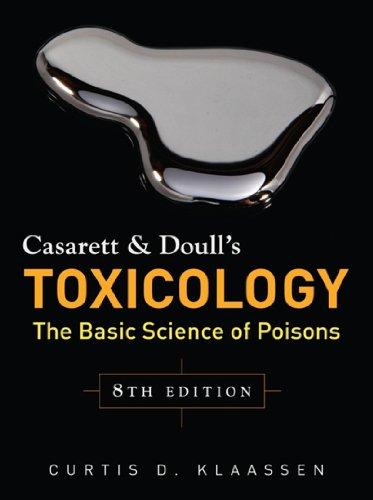

4.13JacobEpstein, MarbleArms (1923).Marble,94cm.Blackandwhite photograph:HansWild,TheNewArtGallery,Walsall.©Theestateof SirJacobEpstein/Tate.147

4.14FromA.H.Smith, AGuidetotheSculpturesoftheParthenoninthe BritishMuseum,revisedbyC.H.Smith(London:TrusteesoftheBritish Museum,1908),p.117.148

5.1ConstantinBrâncuși Torso (Coapsă),1909–10.Whitemarble,24.4cm. MuzeuldeArtă dinCraiova/TheArtMuseumofCraiova. ©SuccessionBrancusi – Allrightsreserved.ADAGP,ParisandDACS, London2023.155

5.2Fromthe ‘H.D.Scrapbook’.H.D.Papers.AmericanLiteratureCollection, BeineckeRareBookandManuscriptLibrary,YaleUniversity,YCALMSS24; usedbypermissionofPollingerLimitedonbehalfoftheEstateof HildaDoolittle.160

5.3TheCalf-Bearer(Moschophoros)andtheKritiosBoyshortlyafter exhumationontheAcropolis, c.1865.Albumensilverprintfromglass negative.MetropolitanMuseumofArt,GilmanCollection,Giftof TheHowardGilmanFoundation,2005.162

5.4The ‘PeplosKore’ , c.530 ,discoveredinfourpiecesin1886.Parian marble,1.2m.AcropolisMuseum(679).©AcropolisMuseum.Photograph: YiannisKoulelis,2018.163

5.5Twomale kouroi (‘KleobisandBiton’).DelphiMuseum(467,1524(statues); 980,4672(plinths)).GettyImages/EducationImages.165

5.6JacobEpstein, GirlwithaDove (1906–7).Pencildrawing.TheNewArt Gallery,Walsall,Garman-RyanCollection(1973.065.GR).©Theestateof SirJacobEpstein/Tate.166

5.7 ‘TheHornsofConsecration’,Knossos.Photograph: Anterovium/Shutterstock.com.CopyrightHellenicMinistryof CultureandSports(N.3028/2002).178

5.8Stairsfromthe ‘PianoNobile’ toanimaginarythirdstorey.Photograph: LouiseA.Hitchcock.CopyrightHellenicMinistryofCultureandSports (N.3028/2002).179

5.9NorthEntrancebefore ‘reconstitution’,fromEvans,ThePalaceofMinos, Vol.III,p.159.©AshmoleanMuseum/MaryEvans.180

5.10TheWestPorticooftheNorthEntranceafterreconstruction.Photograph: AntonStarikov/AlamyStockPhoto.CopyrightHellenicMinistryof CultureandSports(N.3028/2002).180

AbbreviationsandNoteontheText

APAnthologiaPalatina

CantosEzraPound, TheCantos,London:Faber&Faber,1986; referencestothiseditionaregivenintheformofCanto number/pagenumber.

CILCorpusInscriptionumLatinarum,Berlin1863–.

CPH.D.:CollectedPoems, 1912–1944,L.L.Martz,ed.,NewYork: NewDirections,1983.

Eliot, CPTheCompleteProseofT.S.Eliot:TheCriticalEdition, R.Schuchard,gen.ed.,BaltimoreMD:JohnsHopkins UniversityPress,2021,8vols.

EPHPEzraPoundtoHisParents:Letters1895–1929,M.deRachewiltz, A.D.MoodyandJ.Moody,eds,Oxford:OxfordUniversity Press,2010.

IMH

T.S.Eliot, InventionsoftheMarchHare: Poems1909–1917, C.Ricks,ed.,London:Faber&Faber,1996.

InstigationsInstigationsofEzraPound:TogetherwithanEssayonthe ChineseWrittenCharacterbyErnestFenollosa,NewYork:Boni &Liveright,1920.

LSJ

Liddell,H.G.,R.ScottandH.S.Jones, AGreek-EnglishLexicon, 9threvisededn,Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress.

Paige TheLettersofEzraPound:1907–41,D.D.Paige,ed.,London: Faber&Faber,1951.

Pound, Gaudier-Brzeska EzraPound, Gaudier-Brzeska:AMemoir,LondonandNew York:JohnLane,1916.

Pound, LETheLiteraryEssaysofEzraPound,editedwithaninstructionby T.S.Eliot,NewYork:NewDirections,1954.

Pound, SPSelectedPoems:EzraPound,editedwithanintroductionby T.S.Eliot,London:Faber&Faber1928,reprinted1948.

Pound, SPrEzraPound:SelectedProse,1906–1965,W.Cookson,ed., London:Faber&Faber,1973.

PTSEThePoemsofT.S.Eliot,C.RicksandJ.McCue,eds,London: Faber&Faber,2015,2vols.

Lobel-PageLobel,E.andD.Page,eds. PoetarumLesbiorumFragmenta, Oxford:ClarendonPress.

P.Oxy. TheOxyrhynchusPapyri.

TranslationsfromAncientGreek,Latin,andGermanaremyownunlessotherwisestated.

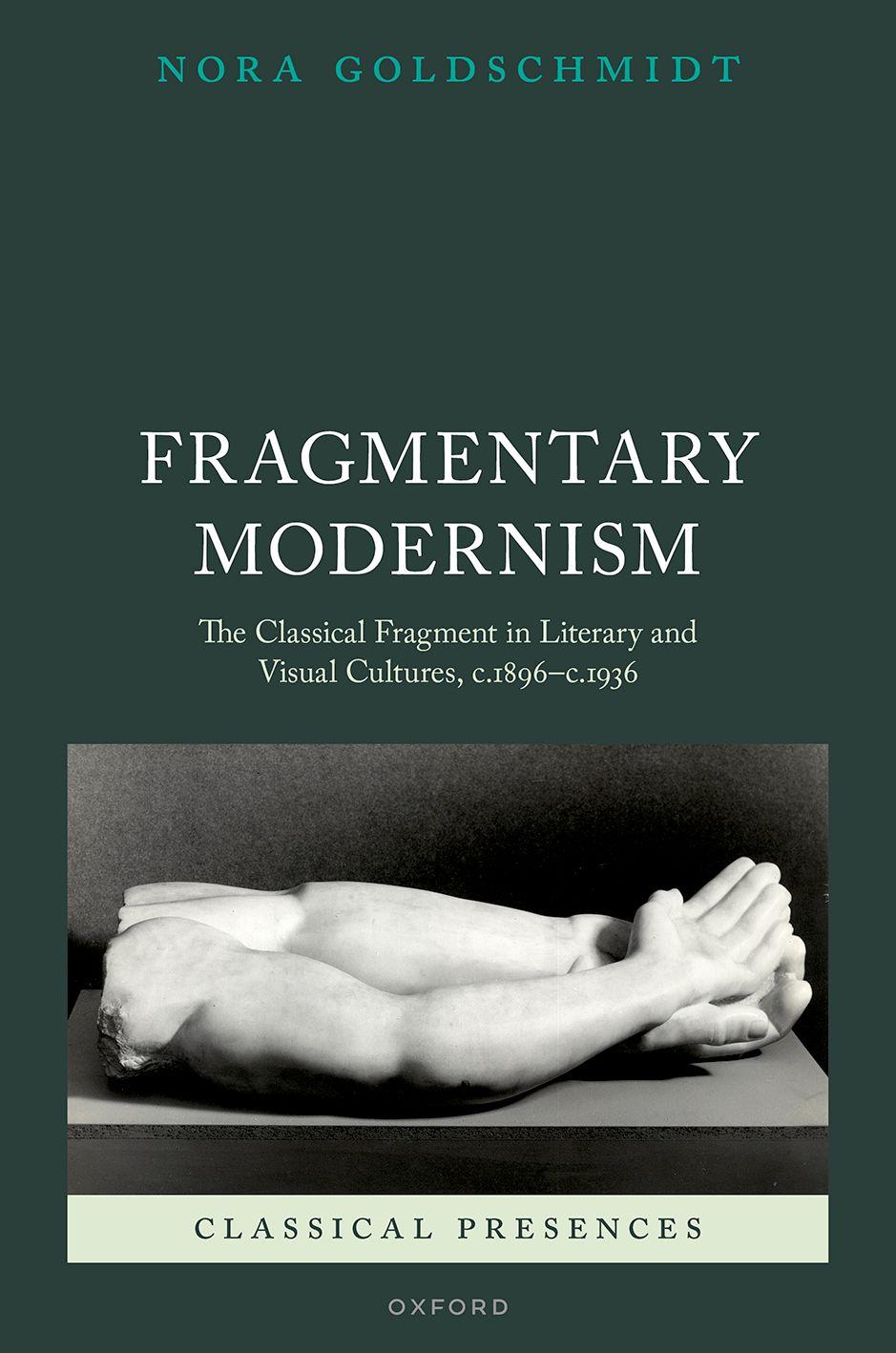

Introduction

ItallbeganwiththeGreekfragments

H.D., EndtoTorment

Half-formedstatues,lacunosepoetry,novelswithnoclearbeginningorend:the fragmentissointegraltotheliteraryandvisualculturesofmodernismthatit bordersoncliché.Scholarsofmodernismtendtoexplaintheturntofragmentary modesintheperiodroughlycoveringthe firsthalfofthetwentiethcenturyasa directresponsetothepressuresofmodernity.InJohnTytell’swords,thefragment became ‘oneofthecallingcardsofmodernism’,largelybecauseitcorrespondedto ‘anewsenseoftheuniversethatbegantoemergeasthenineteenthcentury ended ’.¹Theeconomiesofindustrializationmadeanonymouscrowdsafactof dailylife.Newtechnologies – fromthetypewritertothemachinegun – meantthat themodernistfragmentwas ‘symptomatic’,asMarjoriePerloffputsit, ‘ofwhatwe mightcallthenewtechnopoeticsofthetwentiethcentury’.²When,inthefall-out oftheFirstWorldWar, ‘abotchedcivilization’ seemedtoseveranyreliable continuitieswiththevaluesofthepast,thefragmentedexperienceofmodernity foundastarkcorrelationinthebrokenorabsentbodiesthatbecameavisceral partofeverydayexperience.³

Thefragmentisclearlyentangledinthe modernity ofmodernism,then.Butfor thewidecircleofmodernistswhospenttheirtime ‘pawingovertheancientsand semi-ancients ’,asEzraPoundputit,thefragmentwasnotonlyamarkerof presentexperience:itwasastarkfactoftheremainsofthepast.⁴ Asthe PostclassicismsCollectivehasemphasized,ourrelationshiptoantiquityispredicatedon ‘aconstitutiverelationshiptoloss’ . ⁵ Recentstudieshaveestimatedthatas littleas1–5%oftheliteratureofGreeceandRomebefore200 hassurvived,and the figureformaterialcultureislikelytobeevensmaller.⁶ Fromthevantagepoint ofmodernity,theclassicalpast – despiteitslong-standingconnectionswithan

¹Tytell(1981),3.²Perloff(1986),115.

³Frisby(1985);Childs(1986),chapter3;Perloff(1986);Schwartz(1988);Haslam(2002);Mellor (2011);Weinstein(2014);Kern(2017);Bruns(2018);Varley-Winter(2018).Poundlamentedthe ‘botchedcivilization’ whichledtothewarin HughSelwynMauberley V.4=Pound(1920),13.

⁴‘ARetrospect’:Pound, LE 11.

⁵ PostclassicismsCollective(2020),129.Forthepracticeoffragmenthuntingasessentialtoclassical scholarship,seeMost(1997)withMost(1998),(2011);Derda,Hilder,andKwapisz(2017);Lamari, Montanari,andNovokhato(2020);Mastellari(2021);GinelliandLupi(2021).

⁶ Netz(2020),550–1,557–9;GibsonandWhitton(2023).

FragmentaryModernism:TheClassicalFragmentinLiteraryandVisualCultures,c.1896–c.1936.NoraGoldschmidt, OxfordUniversityPress.©NoraGoldschmidt2023.DOI:10.1093/oso/9780192863409.003.0001

aestheticperfectiondependent ‘onthepropertiesofharmoniouspartscoheringin acontinuouswhole’⁷– ispermanentlydamagedanddislocated,extractedin piecesfromaliencontextsordugupfromthegroundindisjointedshards.

FragmentaryModernism beginsfromthecrucialobservationthattheperiod whichsawsomeofthemostradicalexperimentsinfragmentationinmodernist artandwritingalsowitnessedaseriesofbreakthroughsinthediscoveryand disseminationofGraeco-Romanartandliteratureinfragments.Aroundtheturn ofthecentury,arevolutionintheunderstandingoftheGreekandRomanpast broughtunprecedentedquantitiesofnewfragmentstolightbeyondtheclosed boundariesofclassicalscholarship.AstreamofancientGreektextsondamaged papyrus – includingfragmentsofthelyricpoetSapphowhichhadlainunreadfor thousandsofyears – wereunleashedontopublicconsciousnessinwhathistorians ofpapyrologyhavecalleda ‘mediacircus’ . ⁸ Meanwhile,thenewarchaeology, madewidelyaccessiblethroughrapiddevelopmentsinphotography,wasunearthingfragmentsofmaterialculturefromArchaicandpre-Hellenicperiodsofakind previouslyunseen. ⁹ TeamsofphilologistsfromGermany,France,Britain,andthe USAweremakingcollectionsoftextualfragmentsavailableinaccessibleformats, andinthemodernmuseum – increasinglythesiteofconsumptionofancientart andartefacts – afundamentalshiftinhistoricpracticesofrestorationputthe fragmentonopendisplayasthekeyvisualmarkerofantiquity.

Developmentslikethesewerefoundationalforthemodernistfragment. ApapyrusscrapofSappho,oranArchaictorsorecentlyunearthedfromthe ground,providedstartingpointsfornewartisticproduction.Butthedirectionof receptionalsoworkedtheotherway.Newformsofartandwriting – andthe prominencetheygavetothefragment – startedtomodifythewaysinwhichthe ancientmaterialitselfwasperceivedandpresented.Asphilologists,papyrologists, archaeologists,andmuseumcuratorsabsorbedthenewmodernistaestheticofthe fragment,theytooincreasinglyemphasizedthefragmentarystatusoftheirmaterial,suggesting,liketheirmodernistcontemporaries,thatwithantiquityaswith modernitycompletionwasnotalwayspossibleorevendesired.Recentlydiscoveredtextsandobjectsinfragmentsweretherebynotonlyendowedwiththe thrillofthenewbecausetheyhadbeenfreshlydugupfromtheirlongslumbers underground;theywerealso ‘ new ’ byassociationwiththemodernaestheticofthe fragmentthatwasfastbecomingthecharacteristicmarkeroftheavant-garde. Co-optedintonewdevelopmentsinartandwriting,thefragmentsofthepast wereinvestedwithaborrowedmodernity,asthemodernistfragmentcameto shapetheverymaterialonwhichitwasbased.

OneofthethingsIhopetoshowinthisbookisthatwhathasbeencalledthe ‘apotheosisofthefragment’ inthe firsthalfofthetwentiethcenturywasnot

⁷ Tytell(1981),4;cf.Fitzgerald(2022). ⁸ Montserrat(2007),28. ⁹ Barber(1990).

peculiartomodernism:itwasajointculturalproductionsharedbetweenmodernists andclassicalscholarsengagedinbringingthefragmentsofantiquitytolightin modernity.¹⁰ Theresulthasimportantimplicationsbothfortheunderstandingof modernismandforthestudyofantiquity.Ontheonehand,itallowsusto acknowledgethat,forallitsmodernity,theappearanceofthefragmentinthe literaryandvisualculturesofmodernismwasnotonlyahyper-modernphenomenon;itwas,inimportantways,afunctionofclassicalreception,predicatedona networkofinteractionswithancienttextsandobjectsandtheworkofthescholars whodecipheredanddisseminatedthem.Atthesametime,itisimportanttoface headontheextenttowhichmodernism’sinterventioninclassicalscholarshiphas shapedthereceptionofthefragmentbythosewhocontinuetostudyandcirculate theremainsofantiquity.Surroundedbywhitespaceonthepageordenudedof supplementaryrestorationinthecontemporarymuseum,thefragmenthas becometheprivilegedforminwhichweconsumeantiquityinmodernity.

Acknowledgingthemediatingroleofmodernisminthatconstructioniscrucial notjusttounderstandingthemodernistfragment,butthewaysinwhichwestill engagewithanddisseminatethefragmentsofthepast.

Thegenerativedialoguesbetweenmodernismandclassicalscholarshipthat Iargueforheremightseemcounter-intuitive,notleastbecausethetwoarenas areoftenseenasirreparablyseparatedbywhatStevenYaohascalleda ‘traumatic breach ’.¹¹Ononesideofthedivide,modernistsviolentlydenouncedthe ‘pedagogues,philologistsandprofessors’ whopromotedthestifling ‘cake-icing’ ofclassicalsculpture,andobscuredthevitalityofancientpoetrybyrenderingit ‘ so safeandsodead’.¹²Fortheirpart,classicalscholarsbristledatwhattheysawasthe amateureffortstoencroachontheirprofessionalterritory.AstheChicago classicistWilliamGardnerHalenotoriouslyputitinresponsetoEzraPound’ s HomagetoSextusPropertius (1919): ‘IfMr.PoundwereaProfessorofLatinthere wouldbenothingleftforhimbutsuicide.’¹³

Yetasagroundswellofrecentscholarshiphasbeguntoemphasize,despitethe rhetoricofmutualrejection,modernistartistsandwritersturnedtotheremainsof Graeco-Romanantiquitywithanalmostobsessiveattraction.JamesJoyce’sclassicisms,¹⁴ H.D.’sHellenism,¹ ⁵ PoundandJoyce’sengagementwithHomer,¹⁶ VirginiaWoolf ’sreceptionofGreece,¹⁷ andthedynamicsofmodernisttranslationall – wenowknowindetail – formedactivevectorsinthedevelopmentof

¹⁰ Fortheexpression ‘apotheosisofthefragment’ asappliedtomodernistliterature,seeCollecott (1999),15(citingPatMoyer)andCambria,Gregorio,andRes(2018),29.

¹¹Yao(2019),xv.

¹²Aldington(1915);EzraPound, ‘TheNewSculpture’ , TheEgoist I.4,1914,p.68;Aldington(1915).

¹³ ‘PegasusImpounded’,LettertotheEditor, Poetry:AMagazineofVerse (1919),April,14.1, pp.52–5(55)=Hale(1919),citedin(e.g.)Scroggins(2015),59;CulliganFlack(2015),20,andYao (2019),xv–xvi.

¹⁴ CulliganFlack(2020).¹⁵ Gregory(1997);Collecott(1999).

¹⁶ CulliganFlack(2015).¹⁷ Koulouris(2011);Mills(2014);Worman(2018).

anglophonemodernismandbeyond.¹⁸ Atthesametime,whatElizabethCowling andJenniferMundyhaveidentifiedasthe ‘classicground’ onwhichthevisual cultureoftheperiodwasbasedhasbeenuncoveredtorevealanengagementwith classicalantiquitythatbeliestheviolentrepudiationoftheclassicalpastwhich characterizedtheartwritingofthe firsthalfofthetwentiethcentury.¹⁹

Likerecentstudies,thisbookrecognizestheneedtoreachacrosstheperceived breachbetweenmodernismandclassicalscholarshipbyattendingindetailto modernism’sclassicalpreoccupations.Itbuildsupaninterconnectedpicture –beyondtheindividualcasestudy – ofthewaysinwhichGraeco-Romanmaterial informedmodernistfragment-makingacrossliteraryandvisualcultures.More specifically,itaimstoshowhowmodernistexperimentsinfragmentationwere notpredicatedonantiquity inspiteof the ‘safeanddead’ obfuscationsofclassical scholars;theywereenabledbyavitalcreativeengagementwiththeveryscholarshipthatwassovolublyrejectedintheavant-garderhetoricoftheperiod.The fragmentaryreceptionsofmodernism,Iargue,wouldhavebeenimpossible withouttheworkofthepapyrologistsandphilologists,epigraphists,archaeologists,andmuseumcuratorsengagedindiscovering,deciphering,anddisseminatingthefragmentsofantiquityformodernity.²⁰

Inmappingthenetworksofinfluencebetweenmodernism,Graeco-Roman textsandobjects,andclassicalscholarship,however, FragmentaryModernism also trailsthespotlighttotheothersideofthebreach.Justasmodernistrejectionsof theworkofclassicalscholarswereoftenonlysurfacedeep,classicists’ denunciationofmodernismwererarelyashard-and-fastastheytendtobeportrayed.

J.P.Sullivan,whopublishedareceptivestudyofPound’ s HomagetoSextus Propertius in1964,isoftenseenasthe firstprofessionalclassicistwhowastruly sympathetictotheaimsofAnglo-Americanliterarymodernism.Buttheapparent rupturebetweenscholarshipandartisticproductionwasoftenbridgedandcrisscrossedmuchearlier,andinmorenuancedandlessimmediatelyobviousways.

WilliamGardnerHale’sfatalverdictonPound’ s Propertius isregularlyheldupas anemblemoftheriftbetweenmodernistsandclassicalscholars.Butwhattendsto

¹⁸ Imentiononlythemostextensiveandrecentstudieshere,thoughthepracticeofexplicatingthe classicalreferencesinmodernisttextshasbeenpartofthecriticalhistoryoftheirreceptionfromthe outset.Translationhasbeenaparticularlyfruitfullensforstudiesofmodernismandclassicalreception: seerecentlyLiebregts(2019)(onEzraPoundandGreektragedy),andHickmanandKozak(2019). KaterinaStergiopoulou’sforthcomingworkonmodernistHellenismandthetranslationofGreece, whichfocusesparticularlyonthelaterworkofPound,H.D.,andT.S.Eliot,alsopromiseskeyinsights. Cf.alsoTaxidou(2021)onHellenisminmodernisttheatreandtheatricality.

¹⁹ CowlingandMundy(1990);GreenandDaehner(2011);Prettejohn(2012);Martin(2016).

²⁰ DetailsabouthowsomefragmentaryGreektexts(especiallySappho)orarchaeologicaldiscoveriesinfluencedtheculturalproductionoftheperiodhavebeenhighlightedbefore,butthereremainsno comprehensivestudyofthemodernistfragmentandthedisseminationofantiquityinfragments.See esp.Kenner(1969);Kenner(1971),54–9;Gregory(1997),149–50andCollecott(1999)onSapphoand H.D.;Gere(2009)onKnossos,andKocziszky(2015)andColby(2009)onthegeneral ‘archaeological imagination’ inmodernwriting. 4

gounnoticedisthefactthateven ‘thatfoolinChicago’,asPoundcalledhim,²¹was engagingwithoneofthemajoravant-gardeliteraryoutletsintheperiod.Halewas aspecialistinLatingrammar,whohadspenttimestudyingat ‘theuniversitiesof Deutschland’ whichformedthecradleofrigorousnineteenth-centuryclassical learning.²²Yet,strikingly,hismuch-citedcommentsonPound’sdefectivephilologywerenotpublishedinawell-respectedprofessionaljournalinthe fieldlike TheJournalofRomanStudies or TheClassicalReview.²³Theyweremadeinthe formofalettertotheeditorpublishedin Poetry:AMagazineofVerse: ‘thebiggest littlemagazine ’ andapowerhouseofcutting-edgemodernism,whichhostedsome oftheperiod’sbiggesthits,includingthe firstoutingofPound’ s Cantos (Three Cantos),T.S.Eliot’ s ‘TheLoveSongofJ.AlfredPrufrock’ andpoemsbyJames Joyce,W.B.Yeats,MarianneMoore,D.H.Lawrence,WallaceStevens,Amy Lowell,andWilliamCarlosWilliams.²⁴ Hale,inotherwords,wasactively engagingwithoneoftheforemostoutletsofliterarymodernism.Hiscasual readingof Poetry mighthavefailedtopenetratehistextbookonLatingrammar, whicharguablytypifiestheworkofthe ‘pedagogues,philologistsandprofessors’ thatmanymodernistswereostensiblytryingtoescape.Butinseveralothercases thelinesbetweenwhatHalecalledmodernism’ s ‘maskoferudition’²⁵ andthe academicprofessionalswhodealtwiththeclassicalmaterialbeingprocessedby writersandartistsintheperiodwereoftenfarmoreblurred.Artistsandwritersin the firstdecadesofthetwentiethcenturyclearlywadedintothephilologicaland archaeologicalterritoryofthosewho(inW.B.Yeats’ terms) ‘coughinink’ and ‘wearoutthecarpetwiththeirshoes’,²⁶ butprofessionalclassicists,too,were responsivetotheradicalchangesincontemporaryartisticproduction.

Oneoftheaimsofthisbook,therefore,istoremediatetheperceivedbreach betweenmodernismandclassicalscholarship,notsimplybytakingtheclassical presencesofmodernismseriouslyhereandnow(asStevenYaocounsels),butby showinghowthoseinterdisciplinarynetworkswerealreadyactivefromthe beginning.²⁷ Classicalreceptionstudiesisoftentheorizedasamodeofinvestigationwhichaimstoexposethefactthatthereisnoaccesstoantiquity ‘ proper ’ , sincenothingcomestousunmediatedbythelayersofreceptionthatinevitably distortourunderstandingofthepast.²⁸ Theartisticproductionofthe firsthalfof

²¹LettertoFelixE.Schelling,8July1922= L 245.

²²EzraPound, ‘ProvincialismtheEnemy III’ inPound, SPr,289.

²³Itischaracteristicofthefeedbackloopbetweenmodernismandclassicalscholarshipthat The ClassicalReview playedakeypartinthereadingcultureofmodernistpoets:seeChapter1,pp.17–18.

²⁴ Carr(2012);Hale’sletterwaspublishedintheissueimmediatelyfollowingthepublicationof HomagetoSextusPropertius (sowithinamonthofitspublication).ForHarrietMonroeand Poetry,see Williams(1977);Carr(2012),andBen-Mere (n.d.).Poundhimselfwasthemagazine’sforeign correspondentuntil1917.

²⁵ Hale(1919),55.²⁶ W.B.Yeats, ‘TheScholars’,(1919),ll.7–8.

²⁷ Yao(2019),xvi: ‘Yetwitheveryestrangementcomesanopportunityforreconciliation.And now...thatinitiallytraumaticbreachhasatlastbeguntoheal.’

²⁸ The locusclassicus isMartindale(1993).

thetwentiethcenturyeffectedarangeoflarge-scaleparadigmshiftswhoselegacies arestillpowerfullyactivetoday.Modernismhaschangedhowwethinkabout literatureandhowwethinkaboutart,andthosechangesnecessarilycolourour interpretationsoftheartandliteratureoftheGreekandRomanpast.Forthat reasonalone,modernism’sroleinourperceptionsofantiquitycallsforurgent attention.Morethanjustalensthatmediateshowwelookbackatancienttexts andobjectsfromwherewestandnow,themediationsofmodernismwerealways entangledwiththeworkofclassicalscholarsandthefragmentarymaterialthey broughttolight.Understandingthefullextentofthoseinterdisciplinaryentanglementsnotonlyexposesacrucialdriverintheemergenceofthemodernist fragment;itforcesustore-evaluatetheextenttowhichmodernismisbaked intohowweperceive,construct,andpresentthefragmentarytextsandobjects thatconstituteouraccesstothepast.

Modernism

‘Modernism ’ hasrecentlybeenexpandedonthegeographicalandtemporalaxes totakeinaneverincreasingsetoftextsandobjects.Thetermhasmovedoutwards onaglobalscaletoencompassmodernismsinlocationsasdiverseasTurkeyand sub-SaharanAfrica,andithasshiftedbeyondthe firsthalfofthetwentieth centurytoothermomentsofrupturewiththepaststimulatedbysocietaland technologicalchange,rangingaswidelyastheporcelainofTangDynastyChinato themusicofcontemporaryAfghanistan.² ⁹ The ‘modernism’ coveredinthisbook ismorespecifictothegroupofartistsandwritersassociatedwithwhatEzra Poundcalledthe ‘grrrreatlitttttteraryperiod’ ofmodernismthatsprungup, primarilyinLondon,inthe firstdecadesofthetwentiethcentury:thepoetryof EzraPound,T.S.Eliot,H.D.,andRichardAldington,andthesculptureofJacob EpsteinandHenriGaudier-Brzeska.³⁰

Onereasonforthatchoiceisthattheversionofmodernismrepresentedby EliotandPound,inparticular,hasbecomewhatSeanLathamandGayleRogers callan ‘obsession’ inthestudyoftheperiodroughlycovering1890–1930inBritish andAmericanacademia.³¹Closelyassociatedwiththeterm ‘modernism’,their workwasquicklyabsorbedintotheacademicstudyofEnglish,providing

²⁹ FortheNewModernistStudies,seeesp.Mao(2021)andLathamandRogers(2021),withMao andWalkowitz(2008),738–42andJailantandMartin(2018).Forglobalmodernisms,seeesp.Moody andRoss(2020).Similartranshistoricalandtransborderperspectivesarebeingdeployedinthe discussionof ‘globalClassics’:seeesp.Bromberg(2021).

³⁰ LettertoT.S.Eliot,24December1921=Paige235.

³¹LathamandRogers(2015),4.Astheauthorspointout,itispartlyasaconsequencethattheterm ‘modernism’ iscentraltoEnglish-languagescholarship,whereasit ‘barelysignifies ’ (4)inrelationto otheravant-gardemovements.

paradigmsforPracticalandNewCriticism(‘thetheoryofwhichthemodernist movementsprovidedthepractice’)thatshapedthewaysinwhichliterarycriticism hasbeenconductedinEnglish-speakinguniversities.³²Scholarsofmoderniststudieshaveunravelledsomeofthoselong-standingobsessionsandunpickedtheir implications,butwhenitcomestomodernism’scross-overintootherdisciplines theimplicationsofthatlasting fixationhaveyettobefullyexamined.Themodernist ‘obsession’ hasshapedthestudyofclassicsinunacknowledgedways.Itunderlies practicesofclosereadingthatareusedintheliterarycriticismofancienttexts;itis entangledinmanyofthetheoreticalmodelsimportedtostudythem,andit underwritesourtheorizationofclassicalreceptionstudiesitself.³³Aboveall,the versionofmodernismstudiedhereistightlyimbricatedintheinterpretationand presentationofthefragmentarymaterialonwhichouraccesstothepastisbased. Asthecasestudiesinthisbookhighlight,thewaysinwhichwepresentancient fragmentsonthepageordisplaytheminthemodernmuseumarenotintrinsicto thematerialitself.Theyhavebeen,andinmanywaysstillare,shapedbythe modernistaestheticofthefragment.Understandingthatdominantintervention intheclassicalfragment – andtheinterventionoftheclassicalfragmentinthe obsessionsofmodernism – iscentraltotheprojectofthisbook.³⁴ Thatisnottosaythatthenucleusofthestorytoldherecouldnotbeextended inseveralways.Thefragmentaryimperativeinthe firsthalfofthetwentieth centuryisatransculturalandtransdisciplinaryphenomenonthatinteractswith, butisinnowayrestrictedto,cognatedevelopmentsinclassicalreception.The fragmentworkofPoundandhiscirclewasitselfmarkedbyanoutward-looking ‘transnationalturn’,³⁵ andawiderangeofavant-gardecultureswerealsosimultaneouslyturningtofragmentsinvariousformsandmodes.Interestinthe fragmentcanbeseeninglobalmodernismsfromtheKoreanpoetryofKim KirimtotheUrdu qit’ah ofN.M.Rashed.³ ⁶ Itisthereintheseveredbodiesof Surrealism,thebrokenplanesofCubism,thetechno-aestheticsofFuturism;³⁷ it underliesItalian frammentismo ,³⁸ montagetechniquesin film,³⁹ andArnold

³²Baldick(1996),11withMao(2021),39.Thoughtheyreferredtotheir ‘modern “movement”’,the writersandartistsinthisbookneverquitecalledthemselves ‘modernist’:LathamandRogers(2015),1 (theterm ‘modernism’ was ‘christened’,asStanSmithputsit(Smith(1994),1)in1927withRobert GravesandLauraRiding’ s ASurveyofModernistPoetry).ForthelastinglegacyofNewCriticismsee, e.g.,HickmanandMcIntyre(2012),PartII ‘LegacyandFutureDirections’,andforitslinkswith modernism,seeLathamandRogers(2015),42–52.

³³Eliot,inparticular,isfrequentlyquotedintheorizationsofclassicalreceptionstudies:Hiscock (2020).

³⁴ Forthepressingimportanceoftheinterrogationof ‘interveningmomentsorevents’ thatcan ‘shapethedisciplineinunnoticedways’,seePostclassicismsCollective(2020),4.

³⁵ Park(2019);seealsoGoldwyn(2016)ontheclassicsasworldliteratureinPound’ s Cantos.

³⁶ MoodyandRoss(2020),e.g.,347–51;253.ForthefragmentascharacteristicofJorgeLuisBorges’ ‘globalclassics’,seeJansen(2018),esp.30–51;101–7;122–3.

³⁷ Orban(1997).³⁸ Sorrentino(1950).

³⁹ See,e.g.,McCabe(2005)on ‘cinematicmodernism’ inpoetryandonscreen.

Schoenberg’ s ‘liquidation’ andotherformsoffragmentationinmusic.⁴⁰ The fragmentisacentralpreoccupationofclassicalscholarship,butitalsocharacterizesothermodesofinvestigationwhichwerealsoimportantvectorsinthe emergenceofmodernism,includingdevelopmentsinphysics,anthropology, andpsychoanalysis – disciplineswhich,inEliot ’sterms, ‘madethemodern worldpossibleforart’ . ⁴¹

Thestorycouldalsobeextendedonthetemporalaxis.Modernismisfounded ontheassumptionofaradicalbreakwiththeproximatepast, ‘arebellionagainst theRomantictradition’ (asEliotdescribedPound’sproject)andthemoraland aestheticconventionsofthenineteenthcentury.⁴²Butitwasnotthe firstorthe onlypointatwhichclassicalreceptionandmodernfragment-makingcame together.Fragmentsandruinswerealreadyactiveconceptsandpracticesin antiquity,⁴³andthefragmenthassurfacedandre-surfacedasafeatureofclassical receptionatvariouspointsinitshistory,fromMichelangelo’ s non finito to moderntranslationsofSappho.⁴⁴ Inparticular,the ‘Romantictradition’ against whichmodernismostensiblyrebelledhasbeencreditedwithengenderingan apotheosisofthefragmentlongbeforemodernism.⁴⁵ OnSusanStanford Friedman’sanalysisofthemoveabilityof ‘planetarymodernism’,theRomantic fragmentcouldevenbeseenasa ‘modernistfragment’ beforetwentieth-century modernismeverexisted.⁴⁶ It,too,wassituatedatthe ‘“avantgarde” ofthe “avant garde”’ , ⁴⁷ emergingatatimeofseismicculturalchange,whentheFrench RevolutionputwhatLindaNochlincalls ‘thebodyinpieces’ atthecentreofthe visualimagination.⁴⁸

Yet,asmultiplestudiesofRomanticfragmentationemphasize,themodernist fragmentwasputtoworkverydifferentlyfromitsRomanticpredecessors. ⁴⁹ Romanticfragmentswereofapiecewiththeeighteenth-centuryruinindustry andpopularaestheticdiscoursesofthesublimeandthepicturesque.⁵⁰ Theywere ‘[n]otnecessarily[a]sign ...ofa brokenreality’ (34).⁵¹Theydidnotbring ‘the

⁴⁰ Schoenberg(1967),58.Forfragmentationinmusicalmodernism,seeesp.Guldbrandsenand Johnson(2015)withBernhartandEnglund(2021)onfragmentationinwordsandmusic,includingthe modernistperiod.

⁴¹ ‘Ulysses,OrderandMyth’ (1922),Eliot, CP II,479. ⁴²Pound, SP 17=Eliot, CP III,526.

⁴³Levene(1992);Azzarà(2002);Edwards(2011);Kahane(2011);MartinandLangin-Hooper (2018);Hughes(2018).

⁴⁴ Fortheculturalhistoryofthefragment,seeesp.KritzmanandPlottel(1981);Dällenbachand HartNibbrig(1984);Pingeot(1990);Ostermann(1991);Tronzo(2009);Most(2010);Pachet(2011); Harbison(2015).

⁴⁵ Mcfarland(1981),22. ⁴⁶ Friedman(2015);Mao(2021),74–6.

⁴⁷ Lacoue-LabartheandNancy(1988),133n.2.

⁴⁸ Nochlin(1994).Cf.Lichtenstein(2009),125ontheRomanticconceptofthefragmentas ‘paradigmaticofwhatweusedtocall modern’ .

⁴⁹ Mcfarland(1981);Janowitz(1990);WanningHarries(1994);Janowitz(1999);Thomas(2008); Strathman(2006).SeealsoRegier(2010)onRomanticfragmentationandcf.Lichtenstein(2009), 124–5ontheromanticfragment ‘asawholeinitself ’

⁵⁰ Thomas(2008),21. ⁵¹WanningHarries(1994),34.

dispersionortheshatteringoftheworkintoplay’ , ⁵²andtheytendedtobefuture orientedandhopeful:whatSchlegelcalled ‘fragmentsofthefuture’ (‘Fragmente ausderZukunft’ , Athenäums-Fragmente 22).⁵³Inpractice,thereislittleconnectingKeats’ Hyperion andColeridge’ s KublaiKahn tothefragmentaryrealitiesof TheWasteLand orPound’ s ‘Papyrus’.Still,therearecontinuitiesaswellas rupturestobefound.Romantictheoriesandpracticesofthefragmentfrom Shelley ’ s Ozymandias totheSchlegelbrotherssetimportantprecedentsforthe productionandconsumptionoffragments,notjustforthemodernistwritersand artistsofthetwentiethcenturywhocanbeseeninsomewaysastheheirsof Romanticism,⁵⁴ butforthedisciplineofclassicalscholarship,whichmediatedthe textsofantiquityfornewgenerationsofreadersinincreasinglyprofessional, institutional,andscientificcontexts.⁵⁵ TheRomanticcultofthefragmentestablishedtheformasamarketablecommodityinscholarshipandinartisticproductionintothenineteenthcentury,anditsexpressionandevolutioncanbeseenat variouspressurepointstowardstheendofthenineteenthcenturyatwhatJonah Siegelcalls ‘thethresholdofModernism ’,fromtheaphorismsofNietzscheto HenryThorntonWharton’spopulareditionofthefragmentsofSappho,which werecrucialtotheemergenceofthemodernistfragment.⁵⁶

Ultimately,thestorypiecedtogetherinthisbookoffersjustonewayof repairingthebreach.ItlooksoutwardsbeyondthemajorexponentsofAngloAmericanmodernismtootheravant-gardepractitionersandotherkindsof culturalproduction,anditdigsdowntosomeoftheliterary,artistic,philological, andarchaeologicaldevelopmentsbeforethetwentiethcenturythatcametoshape thereceptionoftheclassicalfragmentintheperiod.Butitsmainfocusremainsa specificmomentofexchange ‘onorabout1910’,asVirginiaWoolffamouslyput it,whenthemodernistculturesthatcametoconstituteafundamentalinterventioninthemodernreceptionoftheclassicalfragmentcametogetherwith developmentsinclassicalscholarshipinintenselygenerativeways.⁵⁷ Theimpact ofanewmodernityseemedtochange ‘humancharacter’,asWoolfcoylyputit, andthemodernistfragmentwasclearlyasymptomofthatchange.Butitwasalso implicatedinafundamentalreconfigurationofthepossibilitiesavailableforthe receptionofantiquity.Itwasultimatelyatthejuncturesandinteractionsoftwo

⁵²Lacoue-LabartheandNancy(1988),48.

⁵³InStrackandEicheldinger(2011),24.Seeesp.Janowitz(1999)onthedistinction.

⁵⁴ Varley-Winter(2018),15.

⁵⁵ Sometimesthecross-overbetweenscholarshipandartwasveryclear:seeesp.Chapter2,p.47n.11 forcollaborationsbetweenFriedrichSchleiermacherandtheRomanticfragment-makerFriedrich SchlegelwithGüthenke(2020),72–95.

⁵⁶ Siegel(2015),237,tracingaspectsof ‘thepoeticsofthefragment’ (208)totheperiod1790–1880.

⁵⁷‘[O]noraboutDecember1910humancharacterchanged’ : MrBennettandMrsBrown (1924). Woolf ’sdatingcorelateswithRogerFry’ s firstPost-ImpressionistexhibitionheldinLondonin NovemberandDecemberof1910,butthedate(andtheplace: ‘inLondonabout1910’),becameiconic, asEliotlaterreflected,forthe ‘pointderepère’ ofAnglo-Americanmodernism(Eliot(1966),18).For thesignificanceoftheyear,seeStansky(1996).