12 minute read

IN FOCUS Vladimir Yatsenko

Art, War & Politics

Vladimir Yatsenko has produced multiple fi lms in recent years, showing a country ravaged by war on its Eastern borders. With the Russian invasion in 2022, guns have replaced cameras for many Ukrainian fi lmmakers. Yatsenko is one of them.

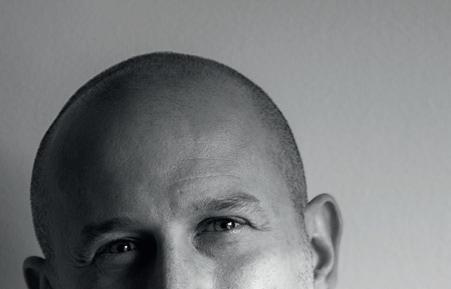

By Andrei Liimets Photo by Aleksandra York

I’m going to have to start with a rather stupid question. How are you and how have you been for the past two months? It’s been a strange time with diff erent universes mashed into one somehow. Right before the Russian invasion I was discussing with my friends if it would happen or not. Everything hinted at it, but it was almost impossible to believe because it’s so crazy. I said to my wife that we have to leave so we jumped into the car, grabbed our grandfathers, grandmothers, cats, dogs, kids – everyone – and moved to Western Ukraine. They started the invasion 4 or 5 hours later so we were very lucky.

We were also lucky to fi nd a small wooden house which was like a Noah’s ark. The next day I had a long conversation with my wife who is pregnant, and we are expecting a boy in the middle of September. We have two other kids, so it was quite a complicated conversation, but the next day I moved back to Kyiv with some of my friends and we started discussing what we could do. We started shooting material about what’s going on around us, just to be witnesses. We decided whatever we would shoot would be free of copyright to everyone just to spread it as much as we can. We started shooting short videos on the frontlines, and one of our videos from Irpin was taken by CNN, and people all around the world saw it.

Since then, working with the press corps has become complicated because Russians started searching and shooting everyone with the press signs, and the Ukrainian soldiers don’t want to allow you to be on the frontline and to get in trouble. After Butcha, we felt it would be impossible to only be witnesses, so we decided to join the mobilisation. Now we are part of the military intelligence service, but we are not trained like special forces, so we do not join all the missions.

You had a couple of fi lms in post-production before the war, so everything is on pause? It’s crazy! A couple of times we managed to go to Western Ukraine for a couple of days to see relatives, and it’s a diff erent world. We still have a big company which is not working now, we are just paying salaries to the people from our own pocket, because they don’t have any other source to live. I don’t know how long we’ll be able to do it. We have at least two fi lms that have approval from A-class festivals this year, and to be honest, I don’t know how we’ll be able to make the premieres with me probably not able to leave the country.

It’s just very complicated to switch between things because, you know, you’re on the frontline and then you’ll get a call about if you made an application to a festival. At the same time, it helps you not to go insane. We all try to adapt to the situation, but it’s getting more and more crazy.

Many fi lmmakers try to avoid politics or keep art and politics separate. Most of the fi lms you have produced are political in some sense. Has this been a conscious choice? Art is part of our life, and politics is part of life. You can’t divide them. I was very disappointed by the

Cannes Film Festival because they put on a fi lm called Z. (The title of the fi lm by Michel Hazanavicius has been changed to Final Cut after the making of this interview – ed.). Z has become a symbol of the neo-Nazis, and for me it’s just a play on some hype, which is immoral because this fi lm had a different name before and now it became Z. The Russian press put it down as their victory, that these stupid Europeans are so weak, they put Z on top of the biggest fi lm festival in the world.

Then they are screening the new fi lm by Kirill Serebrennikov. Fine, now he is a dissident, but earlier he worked with Surkov (Vladislav Surkov is considered as one of the main ideologues for Vladimir Putin – ed.), who is one of the architects of this Nazi regime. They are real friends. He got the money for this fi lm from Abramovich (Roman Abramovich is one of the key oligarchs in favour with the

Vladimir Yatsenko and the film team on the set of U Are the Universe

Russian regime – ed.). When they say it is not political and it’s just art, that’s not true. There’s a sad double standard.

It’s very rare when I can agree with Russians, but at this point, I agree that a lot of Western countries build societies on safe consumption. Nobody is ready to fi ght or raise a voice for their principles, never mind die for them. This is incredible, and I think the reason Putin decided to go ahead with the war; thinking Europe is very weak, they only count money, they don’t care. And this is why he was surprised, and I was surprised in a good way about the common response. But from the cultural standpoint, it’s really strange that the largest fi lm festival supports people who are friends with Surkov, or get money from Abramovich.

Or Sergei Loznitsa, who said that okay, guys, all the Ukrainians must take responsibility for Babi Yar (a site in Kiev where at least 100,000 people were massacred during WWII – ed.), but no one from Russia takes responsibility for what’s going now. This is a kind of double standard which we are dying for right now.

We are talking about the great Russian culture, but at the same time we are having people who grew up with Dostoevsky and Tolstoy shooting children on the

street. I’m sorry, it’s impossible to accept it. There’s probably something wrong with the culture itself, because it’s all part of the same colonial, imperial approach. Building on this cultural background, the new imperial mindset was built in Russia. (Vladimir’s speech turns faster and voice very ironic – ed.) I was a representative of Ukraine at Eurimages, and we had a huge fight just to throw Russia out from it. We’ve been supported by Baltic countries and are very grateful, but it was a big discussion. They called me and I was on the frontline, where a few minutes ago I had been hiding from artillery fire. And then we discussed if Russians should stay! Yeah, probably, yes!

It’s a simple choice and sometimes it’s super simple, because it’s black and white. Later we can discuss the fifty shades of grey, but not now, not when there is war going on.

What about the mindset of Ukrainian culture and films? We are like teenagers sometimes, because as a nation we are teenagers. We are learning a lot. 10 years ago, nobody knew who the sales agents were, how the festivals worked. We’ve been learning, but it takes time. We’re doing it as fast as we can. It takes time to shoot one film, a second film, third film, to make your own mistakes, to grow up as an artist.

How would you describe the state of Ukrainian cinema before the invasion? Great. Probably every big A-class festival had Ukrainian films. Not so long ago it was like wow, a Ukrainian film at Cannes! And everyone was going: oh my god! Now it’s normal. That means the industry has developed. But now the national film fund will not get any grivnas from the state budget, and of course that’s understandable. We have to spend the money on weapons. It’s not about culture, but about our existence.

Interest in Ukrainian culture has increased due to the war. Are there any films you would suggest people see to understand Ukraine and Ukrainians? In most of our films we say something about what’s going on right now. Reflection (dir. Valentyn Vasyanovych, 2021), Atlantis (dir. Valentyn Vasyanovych, 2019), Homeward (dir. Nariman Aliev, 2019), or even The Wild Fields (dir. Yaroslav Lodygin, 2018) that premiered at Black Nights Film Festival, and is based on an amazing novel by Serhii Zhadan. It says a lot about people who live in these territories in Donbass. I really believe some of the most interesting things and approaches are born only when there are clashes between these big tectonic plates, like between Europe and Asia, where different cultures clash and something new can be born.

Atlantis is a 2019 Ukrainian dystopian post-apocalyptic film directed by Valentyn Vasyanovych. It won the award for Best Film in the Horizons section at the 76th Venice International Film Festival. Yatsenko is one of the producers of the film. Not mentioning the war, what would you say are the main challenges for Ukrainian cinema? The biggest issue is that after the war I don’t want us to be just the victims. I see it in the Balkan films, that they still have the trauma, and for us it’s going to be a huge trauma as well, but you can’t think only that. Recently I watched an amazing film Father, which is as simple as the Bible, and you really feel it. That’s something I really want us to do.

Some Ukrainian films about war have been illuminating and prophetic – Atlantis is one example… Absolutely! I joked to the director Valentyn Vasyanovych: motherfucker, why did you set the Ukrainian victory taking place in 2025, why not 2023, it’s too far away!

Film producer Vladimir Yatsenko with his family before the war.

… and Sergei Loznitsa’s Donbass as well. In 2018 I thought it was a good film, I didn’t think it was a great film, it seemed even too cynical. Now it seems as the defining film of the war. You’re absolutely right! But I don’t really like Loznitsa’s films, only because he’s very Russian in a way, like Dostoevsky he doesn’t like people. There’s no kind of empathy, people seem like small ants. I prefer Chekhov who loves people!

Where are you mentally at the moment? Are you afraid? I’m thinking about the fighting which we’ll definitely partake in. Of course, I’m afraid to be killed. Not because of me, I’ve had a great life, but because of my wife. I don’t want my children to be raised without a father. And I’m afraid of not being brave enough, of being imprisoned.

But when you’re on the frontline, it’s not that much scarier than when you’re outside. I’m much more scared here. It was the same at Maidan, because then you are doing something. You’re terrified when you read these things on the news, and it takes energy to be terrified. It’s easier to fight and even die than just to be terrified. Some Ukrainian men escaped the country, which is illegal, and I can’t imagine what kind of personal hell they will live in later.

What would you like to say to the international film community and everyone who wants to support Ukraine? Generally, I would like to say two things: be brave and be kind. It’s important to be brave to raise your voice if you feel something bad is happening in your country or in other countries, it’s important not to be silent. A lot of my former friends in Russia were silent all these years and now they ask: what can we do right now. You lose your dignity drop by drop and end up devastated. Of course, you can lose some money or some steps in your career, but believe me, it’s worth it.

And be kind, because it’s important to help each other. We don’t know who will be next. I’m grateful to everyone who helps our wives and our kids and our mothers in different countries, because right now we can’t take care of them. I really appreciate it. EF

Vladimir Yatsenko born in Donbas,

Ukraine, 43 years old. He graduated from the Kyiv National Economic University, as an economist and also from the Kyiv National I. K. Karpenko-Kary Theatre, Cinema and Television University as a producer.

In 2005 he co-founded the production company Limelite. During 15 years Limelite produced more than 600 commercials and several feature films. In 2020 Vladimir decided to divide the commercials and feature films and he founded the film production company ForeFilms as the co-owner and general producer. The company has several projects in different stages of production directed by well known but also debut directors.

He is a former Head of the Film Industry Association of Ukraine, and also is a member of the Ukrainian Academy of Motion Picture Arts and the European Film Academy. From January 2020 Vladimir became the first representative of Ukraine in Eurimages. He has participated in several training programmes including EAVE, ACE and Midpoint.

Selected filmography: Rock. Paper. Grenade (producer, 2022) by Iryna Tsylik Reflection (producer, 2021) by Valentyn Vasyanovych, premiere at Venice FF main competition. Homeward (producer, 2019), by Nariman Aliev, premiere at Cannes FF Un Certain Regard selection Atlantis (co-producer, 2019), by Valentyn Vasyanovych, premiere at Venice FF, Orizzonti programme, The Best Film award Invisible (co-producer, 2019), by Ignas Jonynas, premiere at San Sebastian FF The Wild Fields (producer, 2018) by Yaroslav Lodygin, premiere at Black Nights FF