13 minute read

CLASSICS Madness

Madness

The Grandfather of Estonian Arthouse Cinema

Madness is considered the first truly outstanding and modernist film in Estonian film history. There are numerous legends around its production and film critics have consistently agreed on the film’s high level of artistic achievement for the last fifty years.

By Johannes Lõhmus Photos by Estonian Film Institute & Film Archive of the National Archives of Estonia

It happened in a small town. The German occupiers had already managed to exterminate all the Jews, Marxists, Gypsies and Partisans. Now, it was time to go after the mentally ill…”

These ominous words open director Kaljo Kiisk’s fifth feature film, Madness. A film that emerges both in Estonian film history and in the director’s filmography as the first work made in a truly modernist spirit. In addition to the symbolic language of the film, and the great work by the actors, the number of legends floating around about the film’s production and distribution processes is subject enough for a film of its own – one full of bureaucratic spite, romantically artistic ambition, grandiose and international ideas, and the iron fist of censorship. This is an exceptional work in every sense, made during an exceptional era – the film shoot was coming to an end in the summer of 1968 right when troops entered Czechoslovakia to silence the Prague Spring.

The action takes place in a mental hospital where a fascist army walks in through the gates with only one goal in mind – to destroy everyone who gets in the way of the regime. Gestapo officer Windisch (Jüri Järvet) arrives at the hospital at the same time as the troops and puts a stop to this monstrous task with his own assignment to expose British secret agents hiding within the hospital walls. The plot prepares the viewer for an exciting game of cat and mouse, turning into a psychological challenge that questions everything taking place and forcing the audience to become intensely involved in everything happening in the film. And, thus, the Soviet cultural authorities’ main criticism of Kiisk’s film was its ambiguity. It was a spiritual provocation that could in no way find offi-

cial approval and which had remained an almost unattainable achievement for Soviet Estonian film art up until then.

THE BIRTH OF MADNESS The film is a modern European co-production that brought together Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians and Russians, but which had a difficult history from its very inception. The screenplay was written by Latvian Viktors Lorencs and it reached Kaljo Kiisk due to the resolute rejection of the screenplay by Riga Film Studio, who found it better not to get involved in making this “moonstruck” story of a madhouse in some unnamed, occupied European country. Kiisk quickly agreed to make the film but the abstract script needed to be rewritten to be more precise, and the detective had to become a fascist, which delineated the time frame for the story and helped “get by” local authorities.1 Thus, they hoped to minimize the ambiguity but retain the artistic generalization and mystery written into the script.

The film stars graduates of the legendary Lithuanian Panevežys Theater, Vaclovas Bledis and Bronis Babkauskas, and there is a small part for Lithuanian theatre legend Juozas Miltinis as well as Valeri Nossik from Moscow and Viktor Pljut and Harijs Liepinš from Riga. And, of course, Jüri Järvet from Tallinn, who went straight from playing Windisch in Madness to starring in Grigori Kozintsev’s film version of King Lear (1970). That was the beginning of Jüri Järvet’s international fame, which soon found him embodying Doctor Snaut in Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972). It’s possible that if Madness hadn’t been banned outside of Soviet Estonia, his name might rank among the aforementioned legends. Kiisk has

KALJO KIISK:

“I had two films banned – Traces and Madness – and we weren’t allowed to show either of them anywhere in the Soviet Union. This situation created its own rules where your imagination was constantly tethered to some kind of limitations. As soon as you started to move in one direction with your thoughts, you were told to turn somewhere else. Your soul and your mind have to be in sync when you are making art – they have to move dynamically and down the same path. But that kind of thinking was impossible at the time and there was nothing you could do about it. I’ve travelled to Argentina and around Europe with Madness and it was well received, even though it’s a relatively old film. But it would have had a completely different effect in its own time because the film is connected to the time and era when it was made.”

Koppel, A. (2005). The Unusual Life of Kaljo Kiisk. [Interview]. Teater. Muusika. Kino, no. 12, pg. 121-128.

1 Viktor Mathiesen, “Eestlased tulevad! Ehk hullumeelsus Gnezdnikovi põiktänavas” / “The Estonians are Coming! Madness Across from Gnezdnikov Street”, Teater. Muusika. Kino, no. 3, 1993. 2 Reet Neimar, “Saatusest määratud? Juhusest juhitud? Üks kild Jüri Järveti elutööst.” / “Determined by Fate? Randomly Driven? A Fragment of the Work of Jüri Järvet”, Teater. Muusika. Kino, no. 1, 1996 3 Boris Tuch, “”Hullumeelsuse” võttegrupp tegi talle kingituse, millele oli graveeritud “Hullule hullumeelsetelt”” / The Crew of “Madness” Gave Him a Present Engraved with “To A Mad Man, Madly”, Teater. Muusika. Kino, no. 3, 2019.

psychiatric

hospitals in Estonia and Latvia.

said that he wanted to work with international actors not only for their talent but also to test how the temperaments of their different nationalities would relate to their personal experiences as members of societies under totalitarian rule.2

Minsk attempted to prevent Russian cinematographer Anatoli Zabolotsky, who was working in a film studio there, from joining the film crew. He was a man who said yes to Kiisk only three days after receiving the screenplay. But since he was a valued professional, the Minsk authorities weren’t keen on letting their guy go make a film with Estonians.3 The Estonians were very lucky to have Zabolotsky involved in the film because his collaboration with the director was flawless, and those who talk about the film always emphasize the outstanding symbiosis of the work of the cinematographer, director and production designer Halja Klaar. The visual world they created on various physical surfaces (mirrored tables, mirrored cabinets, mirrors) hints at the internal contradictions of the characters and helps create an atmosphere where the protagonist starts to see himself more and more in his suspects, finally falling prey to the mad processes he himself started and ending up mentally ill himself. To prepare for the shoot, Kiisk did several months of prep work in psychiatric hospitals in Estonia and Latvia. He later visited the same hospitals with the film’s actors and claimed that “you could still hear the silence that reigned

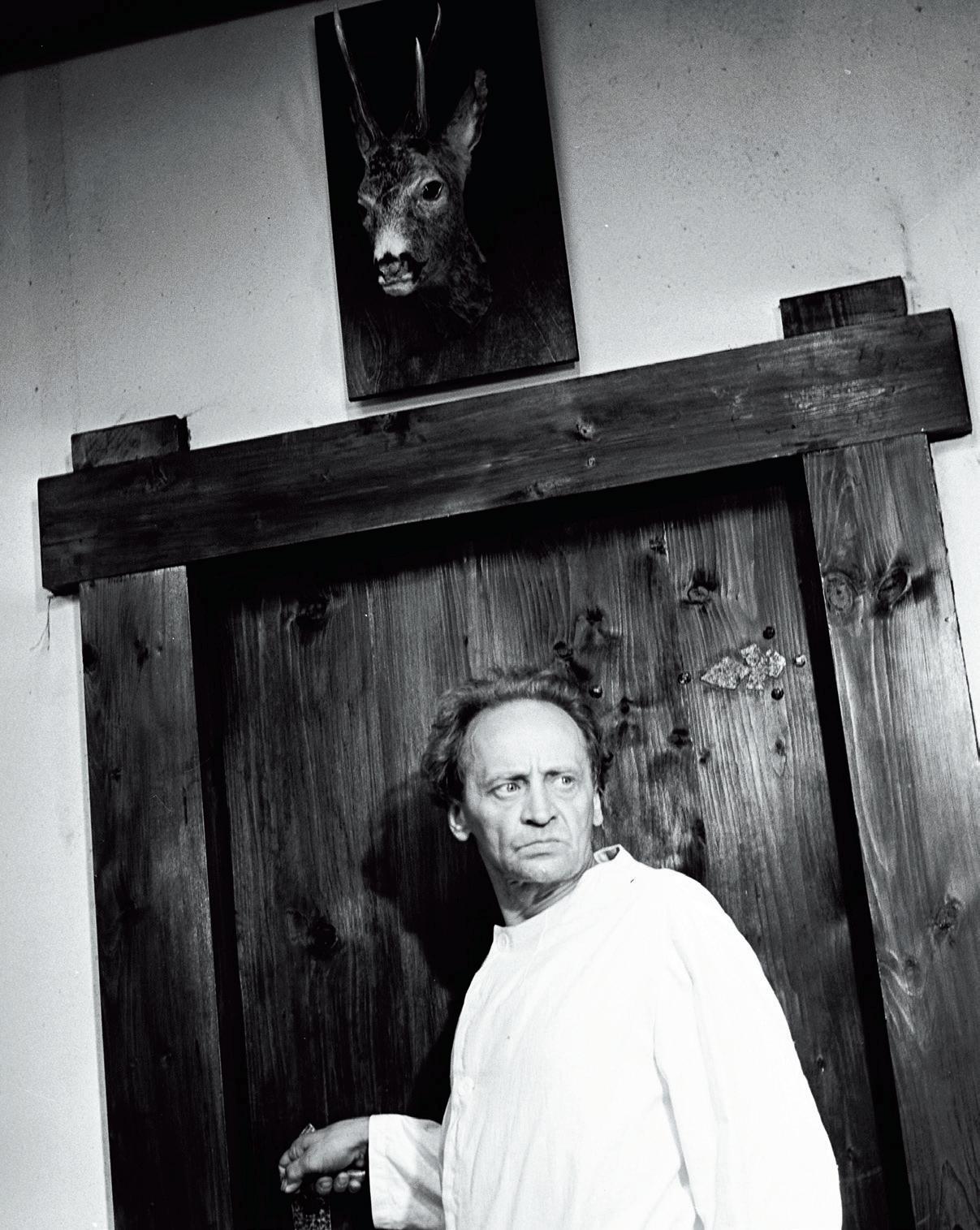

Gestapo officer Windisch (Jüri Järvet) trying to delve into the psyche of the Editor (Valeri Nossik), one of the madmen of the psychiatric ward. in the buses as they drove back – I remember the state we were in as we rode back… After the prep period, the actors brought a lot to the set with them, it was like fireworks on set”.4

They made a request to Moscow for the opportunity to watch some films, not available in Soviet cinemas, with the film crew to prepare for the shoot. The list included films like Franju’s Head Against the Wall (La tête contre les murs, 1959), Welles’s The Trial (1962), Bergman’s The Silence (Tystnaden, 1963), Buñuel’s Viridiana (1961), Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew (Il vangelo secondo Matteo, 1964), and Kramer’s Ship of Fools (1965).5

Some members of the artistic council of Tallinnfilm worked against the film from the beginning, with the later President of Estonia, Lennart Meri, at the forefront of the opposition. Meri wrote to Moscow about the film and made strong recommendations in Estonia that the film would not be greenlighted. So we might only speculate if his activities were responsible for the elevated attention given to Madness, and for the later censorship and restricted

4 Viktor Mathiesen, “Eestlased tulevad! Ehk hullumeelsus Gnezdnikovi põiktänavas” / “The Estonians are Coming! Madness Across from Gnezdnikov Street”, Teater. Muusika. Kino, no. 3, 1993. 5 Andres Laasik, “Filmilavastaja ja näitleja Kaljo Kiisk. Ikka hea pärast” / “Director and Actor Kaljo Kiisk. Only the Good”, Tallinn: OÜ Hea Lugu, 2011, pp. 234.

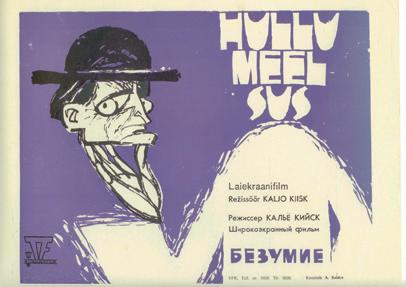

MADNESS

Premiered on February 17, 1969 in Tallinn. Officially allowed to screen in Moscow on January 9, 1987 after which it could screen all over the Soviet Union and internationally. Length: 79 minutes. Produced by Tallinnfilm studios. Shot in Estonia and Latvia. Director: Kaljo Kiisk, cinematographer: Anatoli Zobolotsky, production designer: Halja Klaar, screenwriter: Viktors Lorencs, producer: Arkadi Pessegov. Cast: Jüri Järvet, Voldemar Panso, Mare Garšnek, Vaclovas Bledis, Bronius Babkauskas, Valeri Nossik, Viktor Pljut. There are two versions of the film – one in Estonian and the other dubbed into Russian. The Russian version is about 10 minutes shorter.

distribution of the film by the authorities in Moscow.6

But at first Moscow approved production of the film without reading the screenplay, and merely based on the opinion of the editorial board who claimed the film to be a whole lot less antifascist than the screenplay and future film really were. After the Prague Spring, Moscow suddenly realized that it was a very complicated time for such a film to be made in Estonia, especially as its screenplay was so ambiguous, so they started a correspondence with Tallinn. Amendments began arriving from Moscow for things like changing the title of the film, reshooting some scenes, and adding a partisan squad and armed insurgent uprising to the end of the film.7

Kiisk was forced to make changes before handing over the film, even though he didn’t make them to the extent ordered by Moscow and he didn’t change the title. He did have to leave out the crazed main character Windisch’s horrific vision, for which they filmed material that the director claimed wasn’t even allowed near the editing table.8 There were two versions made of the film – one dubbed into Estonian and the other into Russian. The Russian version is about 10 minutes shorter, and some claim it to be more expressive visually thanks to the laconic editing that eliminates the film’s shortcomings and makes the film more engaging.9

The film got permission to screen only in the Baltic Republics and Belarus, and only nine copies of the Russian version were even printed at first10, which essentially meant that no one could see the film outside of Estonia purely because there were no prints to screen.

Windisch becoming part of the patients under investigation: (from the left) Willy (Bronius Babkauskas), the Editor (Valeri Nossik) and the Person No.1 (Vaclovas Bledis). RECEPTION FOR MADNESS The film was well received by both the local arts council and by critics. Completion of the film was considered a special event not only for Tallinnfilm but also for all Soviet film art.11 Reviews praised the modernity of the concept as well as the balanced consideration of the issues at hand, which vividly characterized the desire of Estonian filmmakers to talk on the central issues of the modern world. The sleekest component of the film is considered to be Anatoly Zobolotsky’s work as cinematographer, greatly responsible for helping to achieve the characteristic two dimensionality of the film’s structure. His cinematography doesn’t play merely for effect or for creating independent meaning torn out of the context of the film, but rather always serve the central idea of the film.12

Polish critic Janusz Gazda also says something about how it marks the birth of great ambitions for Es-

6 Ibid. pp. 227-234. 7 Viktor Mathiesen, “Eestlased tulevad! Ehk hullumeelsus Gnezdnikovi põiktänavas” / “The Estonians are Coming! Madness Across from Gnezdnikov Street”,, Teater. Muusika. Kino, no. 3, 1993. 8 Jaak Lõhmus, “Aktsentide muutumine” / “Changing Accents”, Postimees, 16.06.1997. 9 Andres Laasik, “Filmilavastaja ja näitleja Kaljo Kiisk. Ikka hea pärast” / “Director and Actor Kaljo Kiisk. Only the Good”, Tallinn: OÜ Hea Lugu, 2011, pp. 261. 10 “Kaadris: Hullumeelsus” / “Madness in Focus”, ETV, 16.03.2012. 11 Tallinnfilmi kunstinõukogu protokollist / Tallinnfilm Art Council Report, ERA.R-1707.1.1028, pp. 54.

tonian cinema, highlighting how the film received sharp criticism in the Moscow film journal “Cinema News” for its existentialism and influence of absurd theatre.13

The conditions of Perestroika in 1987 finally made it possible to rehabilitate films like this and thus the official premiere of Madness in Moscow finally took place. The film was also given permission to screen outside of the Soviet Union. There were screenings in Barcelona, Buenos Aires, Munich and London.14 There had been earlier interest in the film by the Venice Film Festival after Italian film historian Giacomo Gambetti managed to see it at a closed screening in Moscow, but unfortunately the film did not get permission to screen at the festival from Soviet authorities, at the time the rule was that no film could be shown outside of the Union without having distribution within the Soviet Union first.15

Film director and critic Andres Maimik has called Madness the first courageous act in Estonian film, which openly contributed to showing conditionality and location as allegorical micromodels of a larger organizational grouping (state, regime, apparatus of repression). The film does everything it can to focus on the metaphorical meaning of its characters – the symbolic Fascist, Madman and Doctor, and to commemorate that contributing to an internal collapse of power is the eternal mission of the mind.16

Film historian Lauri Kärk has written that Madness was the only film in Soviet filmmaking next to Mikhail Romm’s Triumph Over Violence (Обыкновенный фашизм, 1965) that contained self-criticism for a totalitarian regime, i.e. the Soviet system.17

Critic Jaak Lõhmus has branded this film banned from the Soviet Union and international markets as the grandfather of Estonian arthouse cinema.18

MADNESS IN THE 21ST CENTURY Madness is still relevant in the current century. In 2003, the film was screened at the Karlovy Vary IFF retrospective focus on cinema of the Baltic countries. In 2012, Estonian film journalists selected Madness as the second best film of the century (after Arvo Kruusement’s Spring).

The artistic maturity and courageous content of Kiisk’s film still stands out in Estonian cinema today. The mental insecurity of power manifested in the imposition of violence on the poor is no stranger to the populist politicians who divide societies, nor to the people who suffer from their discriminatory policies. With its timeless approach and aesthetically thorough implementation, Madness is a film that doesn’t age, but rather manages to evade every decade that passes from its premiere by adding layers to its meaning that require a longer analysis than allowed by this introductory article.

This is a film that is an ideal choice for any festival, TV channel or VOD platform retrospective program interested in (Soviet) modernist cinema of the 1960s or issues of resistance to regime, closed society or mental disorders. EF

A scene from Windisch's dream sequence shot in the graveyard of the psychiatric hospital that wasn't allowed to be edited into the film.

12 Valdeko Tobro, “Süüta ja süüga süüdlased” / “Guilty and Guitless Culprits”, Noorte Hääl, 21.02.1969. 13 Janusz Gazda, “Põgus kohtumine Eestiga” / “A Brief Encounter with Estonia”, Ekran, 1970, no. 12. 14 Endel Link, “”Hullumeelsusega” Münchenis ja Buenos Aireses” / “In Munich and Buenos Aires with “Madness”, Sirp ja Vasar, 14.08.1987. 15 Andres Laasik, “Filmilavastaja ja näitleja Kaljo Kiisk. Ikka hea pärast” / “Director and Actor Kaljo Kiisk. Only the Good”, Tallinn: OÜ Hea Lugu, 2011, pp. 286. 16 Andres Maimik, “”Hullumeelsus” - modernistlik üksiklane 1960. aastate eesti mängufilmis” / “”Madness” – A Solitary Modernist Wave in 1960s Estonian Film”, Teater. Muusika. Kino, no. 11, 1999. 17 Lauri Kärk, “”Viimne reliikvia” ja “Valgus koordis”: žanrifilmist žanrifilmini II” / “The Last Relic” and “Light in Koord”: From Genre Film to Genre Film II”, Teater. Muusika. Kino, nr 2, 2010. 18 Jaak Lõhmus, “Aktsentide muutumine” / “Changing Accents”, Postimees, 16.06.1997.