9 minute read

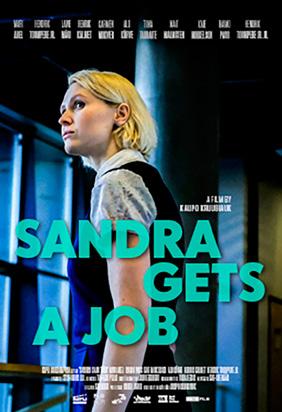

REVIEW Sandra Gets a Job

Work

as the Pillar Stone of Estonian Culture

“Listen, let’s go and have a dance, after all this misery”, the boss says after a redundancy notice given to Sandra in the middle of an office party. “Thank you, not right now”, the doctor of Physics gives her resolute answer, and starts to pack.

Sandra Gets a Job, the debut feature film of Kaupo Kruusiauk, begins with a lab door closing. Every end is the beginning of something new, but the highly qualified Sandra finds herself at the beginning of a tiresome cycle of opening and closing doors.

We probably all have a childhood memory of an affectionate aunt or uncle and their kindly interrogations about your potential career options already during the kindergarten years. The question, “What do you want to become when you grow up?” is as significant in Estonian culture, as the motto of our “national novel”, Truth and Justice – “Work, and love will come”. Estonians’ unquenchable love of work (or is it duty?) is etched into our use of language – the phonetically and grammatically correct definitions of different forms of work could fill a whole paragraph. Our chosen profession may be the centre of our self-determination, or the inevitable part of our daily schedule, we are all in the force field of that four-letter word, one way or another.

I don’t think that anyone asked Sandra about her plans for the future in a kind voice. The fact that the daughter will follow the footsteps of her scientist father was established already at birth, given the family profile. Sandra’s mother Tiina (Kaie Mihkelson) seems to represent the family’s only connection to reality, but it becomes clear soon enough that the Mets family

doesn’t really know any other reality than the world of science. Sandra’s demeanor tempts us to compare her with the heroines of Little Joe or Toni Erdmann, but even more closely to the aforementioned Truth and Justice, toiling away with the same incessant urgency as Estonia’s foremost workaholic, Andres. It seems that nobody has prepared Sandra for a life outside of science and academe. “I have done everything right during my entire life, and haven’t received anything in return”, Sandra says, halfway through her search for a new job. “Maybe there is nothing to get”, the stylish serial start-upper Edvin (Henrik Kalmet) mutters in retort. For him, failure is a way of life. Whiles he’s not inventing the bicycle, he is in the middle of charting all the providers of electricity.

Sandra doesn’t feel comfortable in the start-up world, where the “fail and try again” mentality prevails. She’s more accustomed to the career model of the previous century, where a profession was picked for a lifetime and terms like “lifelong learning” and “soft skills” were not yet born. In society today, where self-determination is largely based on a chosen profession, career setbacks are hard to endure for everyone. The way Sandra keeps on looking despite the obstacles, is worthy of recognition. Determined, like a true-blue scientist, she walks through several assistant positions and the bureaucratic gauntlet of the unemployment office. Sandra is hired as a scientist, a secretary, and a detective. This flipping back and forth between different occupations has been a source of criticism for the film, and considered to make the film too ambiguous. Agreeing with my colleagues, I admit that there is most likely no link between the police detectives and the start-uppers, but different situations illustrate the extreme measures someone is willing to take in order to secure a job. Sandra Gets a Job is, above all, a bouquet of characteristic skits, showing us the nature of all possible work environments in a comical manner.

Depicting work culture is not new on the Estonian cinematic landscape. The image of an industrious slave nation follows us like a shadow, and our films often take us to poor rural households or mansion yards. November (Rainer Sarnet), Manslayer. Virgin. Shadow (Sulev Keedus) and The Riddle of Jaan Niemand (Kaur Kokk) brought along a wave of grim peasant films and enforced the image. Truth and Justice (Tanel Toom) brought to light the tribulations of free landowners. We are celebrating the start-up enterprise today much in the same way we celebrat-

Sandra Gets a Job Depicting work culture is not new on the Estonian cinematic landscape.

By Aurelia Aasa First published in Teater. Muusika. Kino

Female detective (Carmen Mikiver) with her colleagues in Sandra Gets a Job.

ed the potato harvest one hundred years ago. Thanks to Chasing Unicorns (Rain Rannu), this sector even has its own movie. Drama Take It or Leave It (Liina Trishkina-Vanhatalo) convincingly touched upon the weary lives of Estonians working in Finland. The Days that Confused (Triin Ruumet) embodied the spirit of 90s hedonism and entrepreneurial opportunism. Kaupo Kruusiauk has a background in Economics and based his film on his own office years. Sandra Gets a Job takes on the mantle of exploring office work that has not been sufficiently observed in Estonian film before.

An office reflects the changes in society, and has assumed various forms in different periods. The corporate office religion of the 1980s is echoed in the messy desktops, smoking room gossip, and aggressive business talks. The end of the cubicle farm era was predicted in the 90s cult classic Office Space. In the Noughties, we saw a cold boss bitch in her corner office

The cynical lady at the dental clinic is played by actress Tiina Tauraite (below). enter the film market via romantic comedies, valuing her career at least as much as love. Nowadays people are keeping busy in workspaces, including workout gear, and it took a pandemic to grasp the efficiency of the home office, but new towers are reaching into the sky as before, at least in Tallinn. With its minimalistic colour scheme and architectural film language, Sandra Gets a Job resonates with the artificial, bleak nature of offices. At times, Sandra’s dull-coloured world feels like an omnipresent office space. Even at home, Sandra cannot escape the perfect employee stereotype, sitting up straight on the sofa in her embarrassingly spotless apartment.

The unstable professional life of highly educated specialists, chronic underpayment, good girl complex, job-searching, a dysfunctional family and loneliness, are some thematic keywords that the film embraces in one and a half hours. Although the film enlivens the Estonian film canon with its modern thematic approach, most of the feedback has been unflattering, to say the least. On one hand, it’s nice that the trend of blindly praising domestic films is dissolving. The question whether Sandra deserves such a flogging is another matter. True, the film’s rhythm is lagging in places and could benefit from more rapid editing. Breathing space is necessary, but slow milieus and driving shots repeating from scene to scene often stifle the film’s dry humour. Sandra Gets a Job takes its cue from the Nordic masters Aki Kaurismäki and Roy

Andersson. Andersson often prefers carefully sequenced melancholic skits to classical narrative. Despite the static pace, the Nordic old-timers’ mise-en-scène is full of visual rubble. Some decades-old song is humming in the background, someone sips brandy, a wistful couple dances the tango. Sandra Gets a Job does not ensnare the viewer with highly visual bohemian bars or messy homes. And it is devoid of overworked nicotine addicts from the 80s corporate offices, or the cocky charm of the office party gone overboard. Even the alcoholic haze is observed through Sandra’s discreet eyes.

No doubt that Sandra’s alien demeanour adds to the film’s uniqueness. On one side, we see the uncertain world that operates on flexibility, on the other, there is Sandra, a pedantic person living and acting in a very tight square. In her own mind, Sandra has done everything right, and the results would have corresponded to her expectations, had she lived in a vacuum. Adapting to the environment is the main factor in a person’s ability to function. Sandra’s shortcomings in certain skills make her vulnerable, and Mari Abel successfully amplifies that vulnerability. Unfortunately, the self-ironic smirk of the viewer is fixed by the uneven pacing. The film is trying to unite two opposites, universal humour and quiet Scandinavian drama. This results in a dissonance, although occasionally Sandra Gets a Job serves up exhilarating moments. Sandra is like a perfect employee who cannot simply connect with the social code of today. Much like the film itself cannot connect with the code of the audience. Whether this is to be presumed with every feature film, is another matter.

In a low production capacity country, every cinematic work is accountable; and compared to a short animation or a documentary, features don’t have to try too hard to get the attention of the audience. Maybe it has something to do with the recent box office successes, but domestic feature films are anticipated to exceed the high expectations of the cinema-going public. Filmmakers are under pressure to

Mari Abel as Sandra, a woman who has a PhD in Physics and who doesn’t really know any other reality than the world of science. Henrik Kalmet as the young and fearless man Edvin representing the start-up world.

Ink Big!

The critics have done their job

succeed, and in art, like in society, there seems to be no space left for experimentation, or error, much less failure. Big feature film producers are set on their course of high quality with traditional and often thematically safe films.

Granted, every filmmaker has a right and even obligation to choose their own path. But let’s keep in mind that experimenting and risk-taking are just as necessary for the film sector’s development, as the artistic choices that have already proven themselves. In comparison to several other recent feature films, Sandra Gets a Job picks a more complicated route. True, the film’s rhythm gets stuck at times, much like Sandra herself, but its brand of dry comedy with a peculiar dynamic is a breath of fresh air on the Estonian cinema landscape. Ironically, the long gestation period has been good for the film. When Pfizer stocks soared and phone apps mediated the purchase of thousands of home delivery burgers, hundreds of thousands of (simple) workers lost their income, and it’s not easy for them to get back in the saddle. A film about work and losing one’s job connects directly with the here and now. Next to those successfully surfing the new economic boom, many identify with someone struggling to find work, even if it’s on the big screen. EF