9 minute read

Meeting

The year 2023 saw the celebration of the 100th birthday of one of Estonia’s all-time greatest directors, Leida Laius. All of her films are considered classics in Estonian cinema. Annika A. Koppel analyses

Leida Laius’s last feature film, A Stolen Meeting

By Annika A.

AStolen Meeting was the seventh and last film by director Leida Laius (1923–1996), completed on the threshold of Estonian re-independence and during the Singing Revolution in 1988. In addition to the fate of women, a recurring theme in Leida Laius’s films, the film also highlights themes of rootlessness and migration.

As several hundred thousand Russians had migrated and been resettled in Estonia during the Soviet occupation from 1944–1991, the film’s theme was painful and timely. But it wasn’t until the 1980s, when the Soviet regime started to weaken, that people began to speak about it openly. There was actually another film made by Tallinnfilm in 1988 that tackled the theme of migration – Peeter Urbla’s I Am Not a Tourist, I Live Here, which also addressed problems in society caused by massive immigration and lack of housing.

In A Stolen Meeting, Leida Laius continues to talk about children in orphanages, a theme familiar from her previous film Smile at Last (1985). In fact, she introduced this theme much earlier with her documentary films A Human Is Born (1975) and Childhood (1976). A Human Is Born shows a child’s birth, which is a special and happy event, but which also brought the director in contact with mothers who left their babies behind at the hospital. Childhood is a sad film about small children who spend days or even weeks away from their mothers and homes, whether in daycare or even overnight care. That is because there was a time when Soviet women had to return to work a few months after giving birth and had nowhere to leave their children. Director Leida Laius interviewed childcare workers who found that daycare and overnight care are no replacements for a mother. At the time, this was a bold topic to tackle. Childhood was banned and left to gather dust on a shelf because it was critical of how hostile and inhumane the Soviet system was towards mothers and children. Taking this subject on reveals the director’s strongly socio-critical attitude.

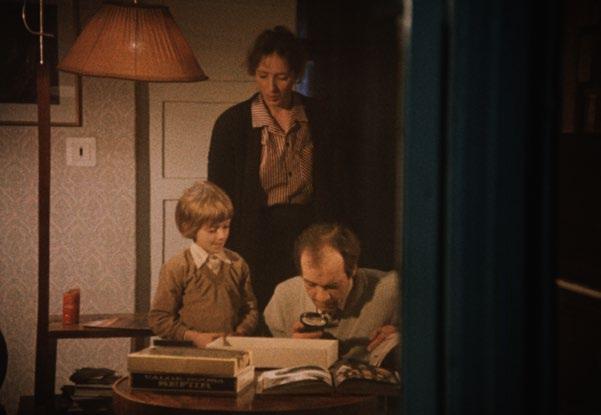

The protagonist, Valentina (Maria Klenskaja, on the right), is Russian but grew up in an Estonian orphanage so she doesn’t know where she’s from. On the picture with Marta Toomingas (Leida Rammo).

THE SCRIPT, THE CONTEXT AND THE PROTAGONIST

The cast includes Estonian top actors(from the left) Kaie Mihkelson, Lembit Peterson, Sulev Luik, Maria Klenskaja.

The script for AStolenMeeting was written by Moscow playwright Maria Zvereva. It was initially supposed to be made in Moscow, but was put on hold and not considered suitable. But the significant social changes that were taking place made it possible to start talking about topics that were previously avoided, so it could be made by Tallinnfilm. Leida Laius was interested in the script but, of course, it had to be adapted as it didn’t make sense to film it in Siberia, the original location for the events. The main character in the film, Valentina, is thus born in North-Eastern Estonia in the oil shale mining region where the largest number of Russians were resettled in Estonia.

The protagonist, Valentina (Maria Klenskaja), is Russian but grew up in an Estonian orphanage so she doesn’t know where she’s from. The film begins when she is released from prison in Russia and starts to look for her son. Valentina wants her child back. The thought of her son left behind in Estonia helped her survive the prison sentence. She embarks on a journey to find her son and win him back. Along the way, it becomes clear who she really is and where she comes from. The film explores not only her external journey but also her internal journey, and how society and her upbringing have influenced her. Valentina is both a victim and a culprit, but also a woman who longs for love and has a right to it like any other human being. But does she have any hope of finding it?

In the train as she is coming back from prison, Valentina meets an old acquaintance named Roma, whose life is probably even harder than Valentina’s. He suggests they keep going together but she has decided to find her son. Valentina wants to discard her old life just like her outdated clothes that find their way into a trashcan.

It turns out that Valentina’s son was adopted by an intelligent family of doctors in Tartu. Her son Jüri is played by Andres Kangur who provides a magnifi-

LEIDA LAIUS was born March 26, 1923 in the village of Horoshevo near Kingissepp (formerly Jamburg) and died in 1996 in Tallinn.

1940 – Volunteered for the Red Army to work as a medic and librarian.

1950 – Graduated from the Estonian SSR State Institute of Theatre.

1951 – 1955 an actress at the V. Kingissepp Drama Theatre RAT.

1955 – Entered the directing program at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK), which she successfully completed.

1960 – Began working at Tallinnfilm studio.

Filmography: 1962 short film From Evening to Morning, graduation film 1965 The Milkman of Mäeküla 1968 Werewolf 1973 Ukuaru

1979 The Master of Kõrboja 1985 Smile at Last with Arvo Iho 1988 A Stolen Meeting

Documentary Films: 1975 A Human is Born 1976 Childhood 1978 Tracks on Snow cent performance. Jüri’s wisdom and understanding are on an adult level. Kangur must have been a remarkable child and he was great find for the director. Sulev Luik also plays a very interesting role as Uibo, the man who Valentina decides to seduce in a plan that ultimately fails. Her saddest encounter is with a former teacher, an old woman still living under Stalin’s portrait whose teaching has shaped young people. It turns out that Valentina ended up in prison not because of what she did but because of the actions of her son’s father. Perhaps she was complicit, but she remained silent and never had him arrested. Maybe because of her generosity or fear, or both.

Also the posters for A Stolen Meeting are quite remarkable. Both are designed by Estonian graphic designer Ülo Emmus.

There is a particularly sharp contrast in the film between the garish conditions in the mining region dorms where Valentina grew up and the doctor’s peaceful, cosy Estonian family home in Tartu. This emphasizes Valentina’s lack of roots. She has nowhere to go and no one to rely one. She is alone and doesn’t belong anywhere.

MARIA KLENSKAJA’S TRIUMPH

The ending of the film reflects all this emptiness, as Valentina understands that she has no opportunity to provide a home for Jüri and it’s better for the boy to grow up in a safe environment. So, she has to disappear. “Don’t write, I have no address.”

Valentina’s role was a challenging and excellent achievement for actress Maria Klenskaja. She is outwardly bold, sometimes pleasant, but then repulsive and inwardly tense and brittle, while remaining a woman who longs for love and understanding. She just doesn’t know how to be a mother, or how to behave, because she never experienced it and was never taught how. And, of course, society offers her no compassion or opportunities for development. Life is simply very harsh and tough towards her. Through her meetings with her son’s father, an old friend, a former teacher, and others, Valentina’s tragedy gradually emerges – even when life presents her with an opportunity, she is not capable of making the best of it and still goes down the path of habit that inevitably leads to problems. But as a person, she longs for love, warmth and a home. And her tragedy is her inability to achieve any of those things.

Maria Klenskaja plays the emotional tones and character’s internal development superbly. Her face reflects Valentina’s alternating hope and despair, weariness and enthusiasm, and she lies skilfully to achieve her goals, or simply out of habit.

Journalist and lecturer Aune Unt wrote this about the film: “Where do you find support if you have no

Ukuaru or Kõrboja1, if you don’t even where or how to create a home? Here, in the bleak industrial city where stunted and bare trees have been left to dry in the ground. These trees are a symbol that starts to form an unexpected and gruesome monument to Stalinism in the film: the buildings characteristic to the 1950s, rows of dry, stunted trees and Valentina approaching like a homeless cat. /…/ But this is Valentina’s home, the land of bleak orphanages and repulsive dorms where a trashy lifestyle and a migrant way of living and thinking know no national boundaries. Over time, the concept of home in a person either shrinks or becomes an obsessive delusion that eats away at them from the inside and drives them to steal.” .“2

Actress Maria Klenskaja has recalled: “After the film was completed, there was an actors’ festival in Kalinin. I was there at the beginning, translating the film. But then I got sick and had to leave. When Leida found out that I was going to receive the award for Best Actress, she called me in the morning and said, “You’re going.” I was in a play about Mary Poppins that was just about to premiere so I didn’t want to take the trip. But then Leida told me in a very specific tone of voice: “Remember, you are not going there to represent yourself, but Estonia!” The year was 1989. And when Lembit Ulfsak and I returned from the festival, then guess who was there to greet us? Of course, it was none other than Leida, herself, waiting at the airport with flowers.”3

Almost all of Leida Laius’s films stand out for the strong acting performances, and not only in the lead roles. She knew how to get both experienced actors as well as beginners or amateurs to play brilliantly in her films. Her own prior acting education probably helped her understand and work with actors. She went to study directing at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in Moscow at the age of 32, when she had already been working in the theatre. Actors have recalled how much Laius supported and appreci- ated them, the attention she gave them and the work she did with them, which sometimes seemed unnecessary at the time. As young actors, they may not have been able to appreciate this approach as they were still struggling with themselves and their surroundings, but they later began to understand its importance. Leida Laius was a very thorough, dedicated and uncompromising director and she expected the same from others.

Maria Klenskaja has also recalled that Leida already had health problems during the shooting period for A Stolen Meeting because once when she went into Leida’s room, she saw a lot of pills scattered on the table. Leida wouldn’t let her talk about it so the crew knew nothing of her problems. But she took care of everyone else.

The Reception

A Stolen Meeting was received well in Estonia and internationally. Smile at Last already screened at the Créteil Film Festival, and A Stolen Meeting was also selected to screen there. There was discussion of organizing a retrospective of her work in France, but unfortunately Tallinnfilm did not have the funds to organize it. In addition to France, Laius also travelled to the United States with A Stolen Meeting for the Women in Film Festival held in Los Angeles where she received the Grand Prix – the Lilian Gish Award. These were important moments for Leida Laius as a director when there was a buzz around her and her work was highly appreciated. She was 65 years old at the time.

It’s sad that there wasn’t much else coming up for Laius after that. Even though Estonia’s re-independence and the period of great change also brought a lot of enthusiasm, the monetary reforms caused people to lose their savings, life was difficult, and there was a shortage of everything. Leida Laius did finally receive the Lifetime Achievement Award from the

National Cultural Fund in 1995, but she did not have much time to enjoy it as she passed away a year later.

In some ways, the themes of a woman’s life and development in Laius’s films are universal and comprehensible to people all around the world. Her work vividly reflects the development of Estonian film art. Laius was a strong player in the masculine film world of the time. Now, as women’s voices are being heard more and more, and work by women directors is appreciated, her work becomes even more relevant. We can be proud that Estonia had a director like Leida Laius during the difficult Soviet era, someone making films that stood the test of time despite her circumstances. All of her seven feature films and three documentaries are high quality works, some more than others. But her place in Estonian film history is secure and, over time, her artistic achievements will start to shine even brighter.

In 2012, Leida Laius’s film Smile at Last was restored and in 2023, a 4K version was made of A Stolen Meeting. The film was digitized from a 35mm film print, which is stored in the film archive of the National Archives. The restoration was made possible through the support of the European film archive association ACE (Association des Cinémathèques Européennes) programme A Season of Classic Films, which is part of the European Commission’s Creative Europe MEDIA Programme. EF