7 minute read

CLASSICS

Corrida

Premiere: 28.02.1983, Tallinn, Estonia Length: 84 minutes, colour

Production company: Tallinnfilm

Shooting locations: Tallinn, Tabasalu, Kuressaare, Saareküla

Screenwriter & director Olav

Neuland; cinematographer Arvo Iho; production designer Heikki Halla; composer Sven Grünberg, producer Raimund Felt. Cast: Rein Aren, Rita Raave, Sulev Luik, Vaino Vahing ori Kromanov, it is safe to say that change of the decade 1970-1980 was the period when Estonian cinema attempted to break out of existing ideological boundaries.

In this historical and political context, Corrida can be considered a successful satirical allegory about the deterioration of power, a glimpse of hope, and the empty solutions, brought about solely by choices based on comfort. The film feels like a critique on conformism even today.

Corrida’s characters introduce several options for how this conflict plays out. Rein Aren, Rita Raave, and Sulev Luik, luminaries of the Estonian acting scene, allow the director to flesh out the intentions of the characters in Corrida. Osvald Rass enjoys the high position of the intellectual elite in Soviet society. He’s not a member of the party, but his writing is favourable in the eyes of the authorities. Osvald swiftly exploits the benefits available for the elite – he has a large apartment, access to rare goods, a sizable income, and the option to work in peace in the local residency. Osvald rents a small island meant for artist residencies, to work on his monography amongst the nature. This is his only goal, he doesn’t feel his position is in danger in any way. Besides, he is certain that the secluded island setting makes him even more irreplaceable for his young wife Ragne. But Ragne becomes bored as soon as they reach the island, the chamber of horrors set up in one of the adjacent farmhouses is enough to excite

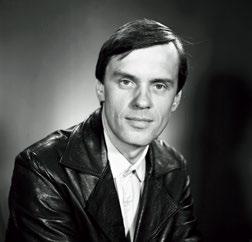

OLAV NEULAND was an Estonian film director and amateur pilot. He was born in 1947 and died in 2005 in a tragic plane accident. them initially, and the purpose of it remains generally unclear. Ragne’s arc seems to be reduced to the function of biological breeding, yet she offers unexpected flashes of temperament and pride, when she dances can-can on the roof to the inept males in the final part of the movie. Ragne is the only one who gets what she wants, although the result comes at a price of renouncement and concession. In that sense, Ragne is a conformist like Osvald and Tarmo, who can basically be read as a younger version of Osvald. Tarmo’s character is solely shaped by the secretive charm and talent of Sulev Luik, his intentions remain vague.

Neuland studied acting in the Department of Theatre of the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre in Tallinn, and cultural education work in the Tallinn Pedagogical Institute. He continued his education in Moscow where he studied in the Higher Courses of Scriptwriters and Film Directors in 1976–1978. In 1969–1972 Neuland worked in Estonian Telefilm as 1st AD, and in 1973–1976 as a screenwriter, editor, and director. He was employed as a film director in Tallinnfilm in 1978-1988.

• His first documentary A Sound Rang in My Breast (1972) was also his graduating film. Neuland continued making documentaries until 1995. Three of his documentaries were dedicated to Estonian organs and organ players.

• Neuland’s best film is considered to be his debut Nest of Winds (1979) that won several awards, like the Best Debut prize in Karlovy Vary and the Best Debut Director award in Dushanbe, at the USSR film festival. Actor Tõnu Kark had his first substantial film role there, and Nest of Winds brought wider recognition to cinematographer Arvo Iho.

• After directing three more feature films – Corrida (1982), Requiem (1984) and In the Age of the Wolves’ Law (1984), and four-part mini-series Mermaid Shallows (1987–1988), Neuland left Tallinnfilm and founded his own small studio Estofilm.

Tarmo, arriving to the island in his swimming trunks, seems to play the role of trickster, or a joker who can upset the whole game and even win, but he doesn’t use this position for some reason and disappears as mysteriously as he arrived. We might ask, was he even was there at all, or was he simply a shadow figure, a mirage that appeared to Osvald one way, and in another to Ragne. Both could project their desires and fears onto the phantom, without having to fear they would be harmed in real life in some way. It would also explain the arising question: how did the rival men get along so well, and why did Tarmo and Ragne’s relationship not evolve to the inevitable, recurring, wild sex? True, sex was taboo in both cinema and literature, although these barriers were sometimes attacked too.

A Naked Woman On A Lonely Island

It is a courageous feat to show the naked female body in Corrida, when Ragne is basically allowed to demonstrate the charms that made her Osvald’s muse. We see a birdcage in several scenes that symbolizes the muse and visualizes Ragne’s character in one allegory. For Osvald, the caged songbird is a beautiful thing to look at and be inspired by. When the cage is destroyed in the finale, we might think this is also the end of Osvald and Ragne, but it’s not. Which, in turn, poses a question about Ragne’s character. Why is Ragne’s fledgling self-awareness and pride being flushed away? Why is she not set free to fly wherever she wants? We can only take a guess.

One of the key Estonian film critics and scholars, Tatyana Elmanovich, wrote in the annual overview of Estonian feature films in Teater. Muusika. Kino (1981-1982): “The whole story of Corrida is reduced to the poor woman’s struggle against two dimwits with pathological impotence. A naked woman on a lonely island, herd of bulls roaring around her, and two men, one young and one old, still not understanding what to do with the woman.”1 Neuland’s film can also be read as the story of Ragne’s tragedy, not Osvald’s. In her female pursuit for happiness and peace, she only stumbles upon wrong guys, remaining but Osvald’s reflection in her conformism. When Osvald’s character went through the biggest change in the film – from contented bon vivant to an old guy owning up to his shortcomings – then Ragne’s character becomes clearer in the process but ends up back at square one by the end of the film, cancelling the journey towards emancipation she had gone through on the island. Tarmo between them is like a transparent mir- ror, showing to both sides that the relationship doesn’t work. Ragne and Osvald both understand it, but still carry on, dragging another young and innocent life into their tragedy.

Luik, Raave and Aren are great character actors who give physical shape to their characters here. Aren’s Osvald is slightly overweight and past his prime, his masculinity is fading and his connection with reality becomes increasingly weaker because of his pleasure-oriented lifestyle. Aren gives concrete shape to this grotesque figure, exercising selfless trust towards his character. He has no issues with depicting Osvald’s weakness, evident both in his appearance and actions.

But Arvo Iho’s camera loves Ragne. Rita Raave doesn’t have much else to do than look beautiful. There is lightning in her eyes even when she opens them barely for a moment. Sulev Luik’s Tarmo is mysterious, unpredictable. As Tarmo comes from cultural circles, he has to carry the motif of the generational gap in the film. Luik’s persona was undoubtedly shaped by his depiction of the alien Luarvik Luarvik in Dead Mountaineer’s Hotel a few years earlier.

The Mystery Of Time

There’s an inevitable stumbling block in the script of Corrida – nature, and the animalistic, wild impulse. In the book, a herd of bulls running around the lonely island unchecked is a force majeure that arrives as suddenly as the storm, the night, or everything combined, as Neuland has emphasized. The arrival of the animalistic impulse, together with the base elements like fire and water, signifies a higher intervention, possibly punishment, but also presents a challenge to handle the issue at hand. This handling implies remorse, purification, and renewal. Osvald goes through that katharsis up to the point where he chases the bulls himself, having declared war on them. You could see that Neuland has tried to single out one bull, a true alpha male who Osvald would go against and fight with (for Ragne). However, these attempts remain weak, the animals don’t seem to have much animosity towards the film crew. They rather come near the camera in hope of getting bread or some other tasty treat, and the audience needs to evoke the necessary fear themselves. Peep Pedmanson wrote: “In the bull herd, physical danger can only be sensed with a really good imagination.”2 It’s true that conflict with the animals might also be interpreted as imaginary, and amplified by Osvald who tries to revive his fading masculinity in the eyes of Ragne. That would also explain the scenes where a confused animal runs around the yard with a piece of cloth on its head. On the other hand, there is no implication that Osvald has staged this scene for Ragne.

Neuland’s Corrida also proves, how difficult it is to relay time in film. The temporal order of events is fractured in the film. We don’t know how long the characters were on the island, when the events happened, and if it was important at all. Ragne utters a phrase about spending weeks on the island, and that would lead us to think that time is relevant, but on the other hand, the events of the film might easily fit into a few days.

Shaky camera, hectic montage and elliptical scenes seem to express Osvald’s inner insecurity, confirming the theory that Corrida is, first and foremost, the story of his evolvement, or destruction. But the status quo prevails, everything repeats, only on another level, and elsewhere. Corrida can mainly be interpreted as a criticism of stagnation, on a personal, timeless scale, as well as a social, historical, and political one. Kallas and Neuland set their characters on the stagnated Soviet stage, to solve their timeless human issues. Corrida is also proof that a good script or a book might not be enough for a good movie. Written conflict and characters need to find life in the new world created by the director. Despite its faults, Corrida is a document about an important development phase of Estonian cinema in a totalitarian society where the repressive grip is starting to weaken. EF