22 minute read

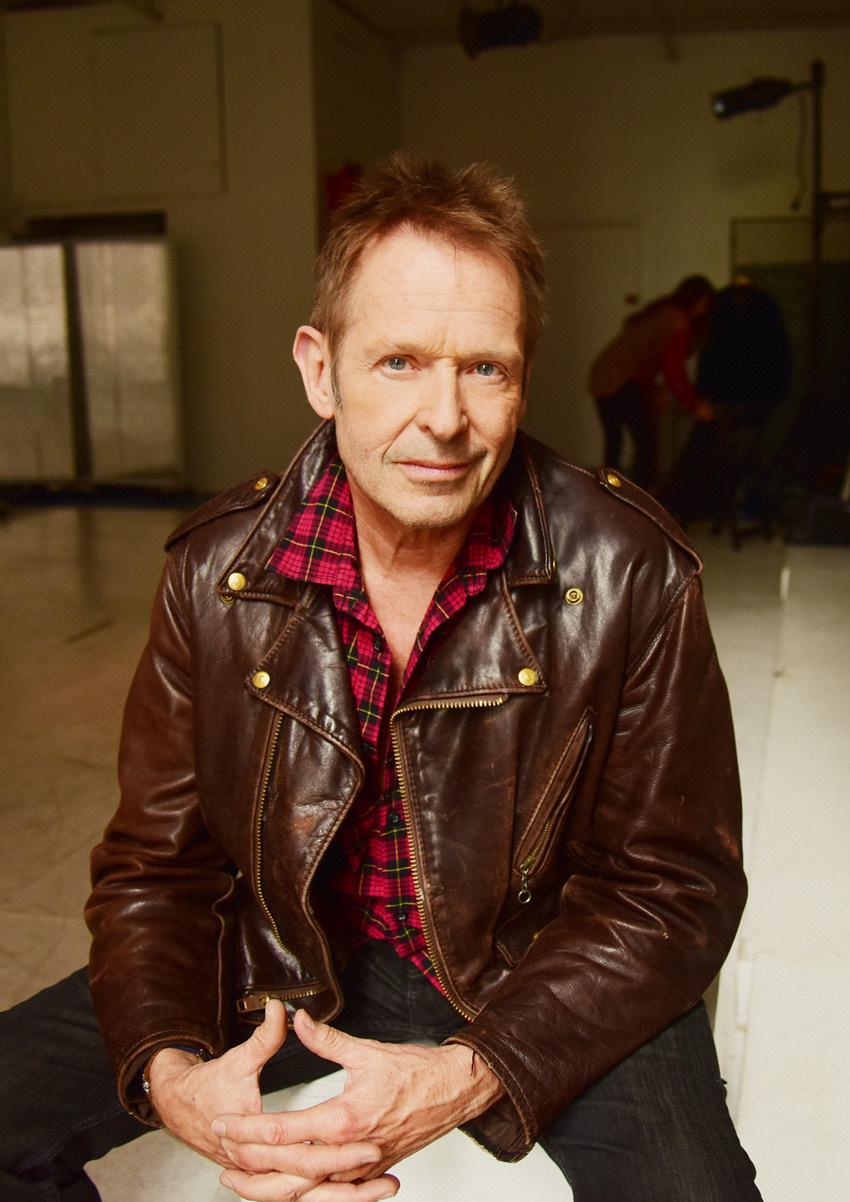

Simon Kirke

Free, Bad Company & A Rock ‘N’ Roll Fantasy

Interview by Kevin Burke.

Advertisement

On the 30th of August, 1970, four young men took the stage at the Isle of Wight Festival. In front of an estimated crowd of somewhere between 600,000 to 700,000 people, the four, consisting of Andy Fraser, Paul Rodgers, Simon Kirke and Paul Kossoff dominated the landscape. This collective known as Free became one of the most enduring acts of the late sixties and early seventies. Formed in 1968, releasing six bombastic albums of blues-rock such as ‘Fire And Water’ (1970), ‘Heartbreaker’ (1973) and the number two smash hit single ‘All Right Now’ (1970), before disbanding unfortunately in 1973, Free came to exist in those realms of rock legends.

From the ashes of Free, two men reconvened to form another supergroup. The two, vocalist Paul Rodgers, and drummer Simon Kirke, linked up with guitarist Mick Ralphs (ex-Mott The Hoople) and bassist Boz Burrell (ex-King Crimson). Together they formed Bad Company, a band that would again blaze a legendary trail. Signing to Led Zeppelin’s Swan Song label and indeed that infamous management of Peter Grant, Bad Company became a steadfast figure of Stadium Rock, that sound which echoed through the seventies. Punctuated by loud guitars, pounding drums and high-pitched vocal acrobatics, Bad Company filled arenas and became airwave favourites. With albums such as ‘Straight Shooter’ (1975), and ‘Desolation Angels’ (1979), the band created a string of what we now term as classics.

This outfit, who stood shoulder to shoulder with the greats of the day, have recently been celebrated in the book ‘Rock ‘N’ Roll Fantasy: The Musical Journey of Free and Bad Company’ by David Roberts (This Day in Music Books). Along with fan anecdotes, the book also includes contributions from the two remaining active members of both bands, Paul Rodgers, and this man Simon Kirke. As the horrible year of 2020 ran to an end, I spoke to the gentleman Simon: a man who lived the life, and now speaks of it with an undeniable honesty. He is a pleasure to converse with; a humorous and genuine person who gave an in-depth truth to both bands and the music he helped create. Alongside this

however, he offered hope for 2021 and a hope that music will survive and always prevail.

The recent release of the book ‘Rock ‘N’ Roll Fantasy: The Musical Journey of Free and Bad Company’ is quite an in-depth read. On a personal level, did looking back through the book stir emotions for you?

Yeah! I mean the short answer is a lot of emotions were stirred up Kevin. Because what I liked about the format of the book is that it’s an oral history. With 90% of it fans writing in and reminiscing you know, with contributions from Paul [Rodgers] and myself. Along with other people that have been involved with us over the years. So yeah, it did, especially the section on Free, that really stirred up some emotions, but stronger than I realized because that was where it all started for me and you know we were just a little gang of kids really.

With some 350 fan anecdotes, readers are given the eye witness, audience impressions of both bands at their heights. Do you feel that makes it the best account so far?

Wow, yeah, I mean there are people that have grown up with our music, and in fact, I am doing that show [Stageit. com] in a couple of weeks, and people are sending in requests and they are saying ‘Oh, my grandfather loves the intro to ‘Shooting Star’’. Oh wow, you know there are people now my age, and I’m 71, so there is a whole generation of people who grew up listening to Free, and then a little later with Bad Company, and they’re passing on their musical tastes to their kids and now their grandkids. It really is amazing, it’s wonderful and it is very humbling.

You are a very versatile drummer, and some may not be aware that you appeared on recordings by the American blues and boogie-woogie pianist Champion Jack Dupree (‘68) before Free. How did that come about?

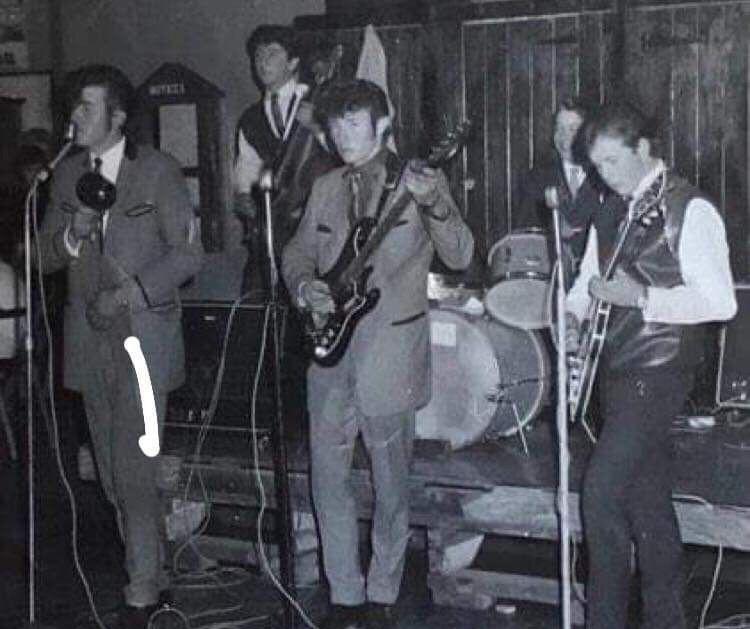

Simon with The Maniacs, 1964

Well I had just joined Black Cat Bones, and it was one of those amazing pieces of faith. I was stuck in my little bedsit in Twickenham, and I heard about this band that was playing in the Nags Head pub across town. I was really intrigued by the name, I mean I knew nothing about them but Black Cat Bones was such a great name. But it was a long way [to travel], and I tossed a coin, I literally tossed a coin, and it came down heads, and heads determined that I was going to see them. Long story short, they were looking for a drummer. Their guy was leaving or getting the sack. But Paul Kossoff, who I’d befriended, you know, praised me during one of the breaks. So he said, ‘You know we’re having auditions tomorrow?’ I got the job and only after perhaps literally two months, we were recording with this guy called Champion Jack Dupree and he was a New Orleans barrelhouse piano player. And I’d never been in a recording studio before Kevin, so I was really nervous. Especially because this guy was a bit of a legend. But, we just played our little set with him, we did several shows with him prior to that, I think a couple shows, and he liked me, and he liked my drumming. I had never gotten an endorsement of my proficiency before from anyone, least of all someone who’s a legend, this was a man who can play and I was like ‘Wow’. So then it was into the studio to do ‘When You Feel the Feeling You Was Feeling’ [album, 1968]. I think they were up all night thinking of that title [laughs]. It came out, I don’t think I heard it since the day I played on it, but that’s how it all came about.

Who do you feel was the most influential person or musician on your drumming? Or did you have that jazz influence like that of Ginger Baker and Charlie Watts?

Not really, although the first time I ever saw anyone playing drums was on a big band show called ‘All That Jazz’. I suppose that swing drumming, that big band drumming, it is not that far removed from rock and roll, and from Jive. But honestly, I am in adoration of those drummers, but it’s not my style.

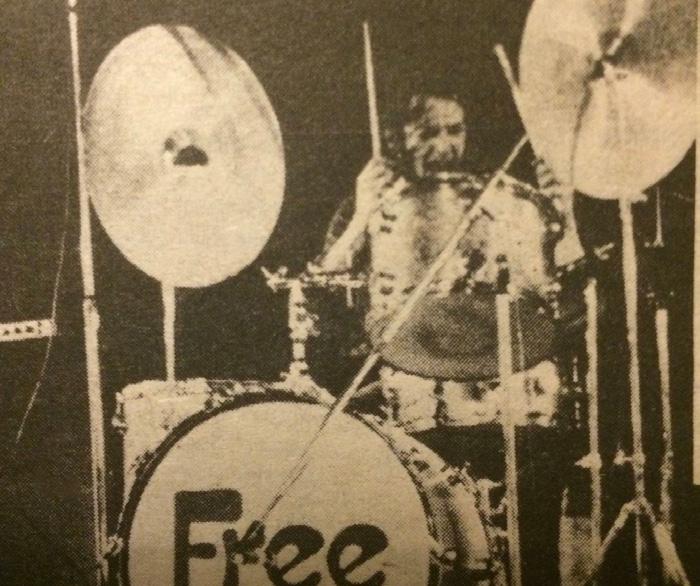

Free

I guess the guy that really came out of that whole pack to me was Buddy Rich, and he was staggeringly good. My main influences were black music - Soul, R&B, and my number one influence was Al Jackson, Jr. who played with Booker T and the MGs. He did mostly Otis Redding and he played with the Stax House band in Memphis and his drumming was just excellent. He’s the governor as far as I’m concerned. But I had many other influences that shaped my playing. Ginger [Baker] was great and a wonderful drummer, and Charlie Watts he has one of the great backbeats, he is one of the greatest backbeats in the world, but he’s very much influenced by Jazz. Levon Helm from The Band, and Roger Hawkins who played with the Muscle Shoals band. They were mainly out of Alabama and they were the house band for so many artists, such as Wilson Pickett, and Aretha Franklin. So I guess they were the handful of influences on me, but Al Jackson, Jr. was the number one.

In the space of just four years, Free accumulated a legendary status. Recording six albums in that time (as well as a live album. 1971’s ‘Free Live!’) must have meant it was a complete whirlwind. Did the band take over every aspect of your life?

Yeah, yeah, true. Things were different back then. We were a lot younger back then ... we all kind of rose to the challenge. With a couple of the albums, like on ‘Fire And Water’ and ‘Highway’, some of the songs were recorded between shows. We’d come back to London, or we do a couple shows in London or the home counties, and the next day we’d be in the studio cutting a couple of tracks, then go off and do some shows again. So I guess the bottom line though, Kevin was that it really became too much even for these young lads. You know it really became a workload, a kind of beast that ate itself. I guess that’s how I’d put it [laughs]. We wanted to build a following, we worked all hours God gave us… well, that God and Island Records gave us. We’d travel the length and breadth of the UK building up a

fan base. So when ‘All Right Now’ hit, I mean, we’d had this sort of fan base that we’d been building and it just was like a springboard. Suddenly, we were playing to thousands of people in theatres instead of little clubs, you know. Then of course the pressure was on to release a follow-up to try and capitalize on the commercial success of ‘All Right Now’ and ‘Fire And Water’ and we couldn’t do it. We weren’t the sort of band who could write to order. We just wanted to play our music and if it was popular then it was popular, if it wasn’t then so be it. So ‘Highway’ [1970], the follow-up to ‘Fire And Water’ was a flop and the single that followed it, ‘The Stealer’ [lead single from ‘Highway’], that didn’t do anything either. We were demoralised and we broke up.

So there was a pressure then from the record company to bring out another hit, another ‘All Right Now’?

Absolutely. It’s funny because Island Records at the time were considered an artist-friendly record label. I mean Chris Blackwell was a great guy, but once ‘All Right Now’ came out and became this monster hit, they kind of changed their clothes a little bit and they became ‘We need an album to follow up, we need a single to follow up ‘All Right Now’’ and it was impossible. The workload increased, instead of playing a different town every night, suddenly we were playing a different country every night. Being so close to Europe, we all jetted of to Holland, or Belgium or France or Sweden. It really got out of control for us to the point where Paul Rodgers was the first guy to say ‘Fuck this! I want to rest, we want some time off’. Then breaking up, I mean the first time that we broke up, really hurt Paul Kossoff, he was never the same. He got into drugs, and he went downhill very quickly. So we reunited, I believe about a year later, to try getting him out of the doldrums, when what he really needed was rehab, but we didn’t really know that at the time.

By the time Bad Company came

together, did you, and Paul in particular have a better plan and idea of how to succeed?

Yeah, I mean, Paul put it the best: ‘We want to be the biggest fucking band in the world’. What we wanted to do was just play music unencumbered by a bunch of monkeys on each other’s backs. Free, when it broke up was traumatic, it was traumatized. It had a history of pain. With Paul Kossoff ‘s demise, he had gotten so hooked on drugs. But, Mick Ralphs came out of Mott the Hoople, he was ready to leave, he wasn’t happy and then we found Boz Burrell he’d been kicked out of King Crimson. So there were four guys from three different bands, who just wanted to play music the way they wanted to play it, and it worked a treat. We all got on, we all drank a little bit, we all smoked a little bit a dope, but nothing terrible, we were happy. Meeting Peter Grant and Led Zeppelin’s Swan Song label and being hooked up with them was a marriage made in heaven ... and we took off like a rocket.

How influential was Peter Grant on the creativity of Bad Company? Did he let you have an almost free reign in the studio?

Yeah, he just said ‘You make the music and I’ll do the management’. And that’s basically what he had done with Zeppelin. When Zeppelin were formed, you probably know this, it was The New Yardbirds, and they were called The New Yardbirds to honor a contract that had yet to expire. So the first half dozen gigs they did was under the name of The New Yardbirds. The band was put together by Jimmy Page and Peter Grant, so Robert [Plant] and Bonzo [John Bonham] for a short time were hired hands. So Peter Grant’s way of doing things ... he was very clever, very smart. We had a handshake agreement. Obviously we had to sign papers a little bit down the way. For want of a better word, he was a good manager. We found out later that there had been a bit of conniving when all the dust settled. Swan Song broke up, and Peter Grant eventually died 25 years ago, but we found out that we had signed away quite a little bit of our

money to him in perpetuity. We were like so many bands of the sixties and seventies who were taken advantage of by management. But at the time we were happy just to be free of the bonds of our previous bands. The first five or six years of Bad Company was just outstanding.

When Bad Company started, do you feel there was an expectation that audiences expected Free in another form? And was it difficult to separate yourselves from the legacy of that previous band?

Good question. We did field several calls at various concerts, play ‘All Right Now’ or play ‘Heartbreaker’. I remember one gig when Paul said, ‘Listen! We are Bad Company, we are not Free mark two, this is a brand new band’. That got a big round of applause, but the other side of things is there was a lot of affection for Free, even though we were only around about four years. It still resonates today, there’s a lot of affection for the band, and I think the fact that we were now, as Bad Company playing 90% of the time in America, a lot of people thought we were an American band over here. I think there was a little resentment, a little wistful resentment that we had left England and come over to America. But that’s the way the cards were dealt. We took advantage of the fact that we could tour America pretty much incessantly, and not play the same market twice. Of course England and the UK were much, much smaller. I like to tell people over here [America], ‘You can fit England into Lake Superior’. We were quite happy over here, and we did go back to England several times, and toured to great success. Then it did start to unravel around about 1979, 1980.

There was an upheaval between ‘Desolation Angels’ and ‘Rough Diamonds’ (1982). Was that the marked low point of your career?

For sure, yeah. Well, ‘79 was really, I think, the last really good album from Bad Company. ‘Desolation Angels’ was really, really good, but we followed that

Bad Company

up with a hundred date tour. Something like a hundred dates. I was drinking too much, and taking coke, other members of the band were as well. We were all getting a little crazy. Then that took us into 1980 when the tour finished, and of course that was the horrible year, 40 years ago. Lennon was shot, and Bonzo died, Zeppelin broke up, Peter Grant went to pieces, and the management fell apart. Paul Rodgers said ‘I’ve had enough’ and he went off. So yeah, it was a rough time, very rough.

Did that mean that the whole support structure for Bad Company was literally gone? And the band was another victim of John Bonham’s loss?

It was hard, and we fell apart, and we were all pretty fucked up at the time but this was really….when Peter Grant went into seclusion, Swan Song and Zeppelin broke up, Robert and Jimmy left Peter Grant’s management, we were pretty much on our own. When Paul left, we just kind of twiddled our thumbs for a couple of years. I went into rehab, and I was at a real low point for sure. But what they do say is ‘What doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger’. A few years later, for better or for worse, certainly in terms of Bad Company’s career, which will always have a question mark over it. When we reformed with another singer, that kept the name alive with Brian Howe, but it took Bad Company down a different direction, a different musical road.

Simon continued about that time:

I just want to say that Brian died recently [May 2020]. It’s funny when someone close to you, I mean that in the literal sense, we worked together for several years, we didn’t get on, I won’t pretend we did. But he was a hard worker, and when someone dies all bets are of the table, and all animosity I harboured for the guy is gone. Because a mother’s lost her son, a daughter’s lost her father. He did what he could. We were under a lot of pressure to continue the band, and it’s funny, I was looking back over some of the Bad Company with Brian Howe

concerts [on YouTube], and some of the comments that accompany songs, there are a lot of people who liked Brian Howe, who thought he was a better singer, in some ways, then Paul. I’m not suggesting that at all, I much prefer Paul’s singing hands down. But we did keep the name alive. I think had we not gone with another singer, I think the band would have died and that would have been it.

That decade of the seventies was bookended by tragedy, with Joplin, Morrison and Hendrix at the start, and Keith Moon and Bonham towards the end. I take it from how you speak, you are aware of how lucky you are to have survived it?

I gave up drinking and drugs years ago and that certainly did help. It took me a while, I won’t lie, but it did take me quite a while to put it all behind me. But, I am a survivor, a lot of my friends didn’t make it, but I help. I’m involved in a couple of societies, charities that help kids with addiction and it keeps me on the straight and narrow.

Now, with your solo albums, do you find yourself measuring your work to what you created in the past?

No, my creed is that ‘I just want to make music that I like’. I know it’s not going to sell. I’m beyond that, I’m kind of a dinosaur, and I’m out of that loop. I make songs that I like. Fortunately, the only reason I would like them to sell is just for my own insatiable ego. It’s not going to make me a lot of money, and the three albums that I’ve made, I can look back with pride and say ‘You know what? They were pretty damn good!’ As long as my kids like them, then that’s all I need, that’s good enough for me.

You have a very powerful, bluesy voice and I guess that comes from years of doing backing vocals to Paul Rodgers?

Paul’s singing and my singing are miles apart. He’s very soulful, I’m much more melodic. I’m more McCartney and I guess Paul’s more Otis Redding. He’s a phenomenal singer and he gets

better and better with age. I did sing before Free and Bad Company. I had a band called Heatwave and I was the lead singer. So I’ve always sung, but when Paul came along obviously we started out as a sort of Blues-based band, harmonies were not really required until we came to do ‘Tons of Sobs’ [1969]. There was a song called ‘Over the Green Hills’, a little acoustic song that Paul came up with. He wanted to do these harmonies, [sings] ‘La la la la’ with me, him, and Andy Fraser. We did this three-part harmony and it was like ‘Wow, that’s nice!’ So really, I became a backup singer from then on, and did the harmonies on ‘Feel Like Making Love’ and ‘Shooting Star’ [both from ‘Straight Shooter’]. Then I got to write my own song. I did a couple songs that I wrote with Bad Company, and I co-wrote the song ‘Bad Company’. That was a big lift for my songwriting prowess. That really put my kids through college that song, it’s amazing.

Looking at your upcoming show for Stageit.com*, are you prone to throwing in surprises or obscure tracks at those events that don’t get the attention they deserve?

Very good question. Yes, is the short answer. I am putting in a couple of things that probably people haven’t heard. And I’ve asked people to ‘ask for their requests’. I’ve had a couple of requests and I’ve been like ‘wow, I barely remember that song!’ ... [something from] the ‘Kossoff Kirke Tetsu Rabbit’ album [1972], which is in some ways a solo album. Someone asked for a song called ‘Dying Fire’, which I think was the first song I ever wrote and I’ve got to dust that one off, and it’s actually really nice. I am going to do a couple of the hits, of course I am. But I’m a little limited in what I can do by myself, but I am going to do some backing tracks, I’ve got my studio here. So I will be playing with me, backing myself on a couple of songs. But there will be a couple of surprises I guarantee.

*Interview conducted before 18th December.

Can you see any plans for 2021 as yet?

Oh yes, now we have the vaccine coming round the corner, though I don’t see ‘us’ playing until this time next year. I was talking with Mick Fleetwood recently, because everyone is just dying [to tour], like greyhounds waiting for that rabbit to come around the corner and the traps to spring open. We are all dying to get out there. I said, ‘How about we go out on a package tour with Fleetwood Mac, Bad Company, Aerosmith and the Eagles all on one bill?’ [Laughs]. I thought, ‘Wouldn’t that be something?’ There are plans currently, I can’t reveal anything yet, and I don’t wanna jinx it. But, it will be late 2021.

I spoke to Arthur Brown recently, and even he is looking forward to touring next year, and I know you’ve crossed paths in the past?

It’s funny you should mention Arthur Brown, and package tours, because Free was involved in one of the great package tours of the late sixties. It was opened by Free, we would have twenty minutes, then it was The Crazy World of Arthur Brown, then it was Joe Cocker, the Small Faces and The Who. All on one bill. That was a helluva show, I can guarantee you. Back then, The Who were at the height of their powers. In 1969, they were the best live band in the world. They really were absolutely stunning. You know Moony [Keith Moon] was only about 19, and an incredible drummer. You had the Small Faces with Steve Marriott, and they were all in their early twenties and they were peaking; Joe Cocker had the big hit, ‘With A Little Help From My Friends’. It was just a magical night, and we got to see it for about twenty-five shows. It was stunning.

One final thing Simon: Last year (2019), we celebrated fifty years of Woodstock. Is it true Free or even Paul Rodgers turned down the festival?

Ah! What happened was, we were in New York. Yes, we were in New York

doing the Blind Faith tour. And we had, I believe, a week off. I remember walking into my manager’s hotel room, Tony Glover, Tony Glover from Island records, and he’s on the phone talking to someone, and he put his hand over the mouthpiece and said ‘Listen, there is this festival upstate, it’s about five hours away. We got no gear, it’s going to rain, do you want to do it or you can have two or three days off ?’ I think Paul was with me or maybe he heard a half an hour later, but we emphatically said ‘No! We don’t want to do it’. And that was Woodstock. I think we as a band told our management, ‘No, no, no fucking way are we going to do it’, and we turned it down. The only three days we had off, we weren’t going to slap all the way upstate. So yeah, we turned it down [laughs].

Dedicated To:

Paul Francis Kossoff 14 September 1950 – 19 March 1976

Andrew McLan Fraser 3 July 1952 – 16 March 2015

Raymond “Boz” Burrell 1 August 1946 – 21 September 2006

Brian Anthony Howe 22 July 1953 – 6 May 2020

officialsimonkirke.com

www.facebook.com/ SimonKirkeOfficial