9 minute read

eSPORTS A REAL GAME CHANGER

BY RICHARD G. BIEVER

When Tyrese Ellis was a high school freshman, his future looked uncertain at best. He admitted he lacked motivation and was “borderline failing” most classes.

“I was a heavy gamer,” he said. “I wasn’t heavy into going to school.”

When the Fort Wayne Snider senior says “heavy gamer,” Tyrese means video games. He played them nonstop, mostly alone in his bedroom. Back in grade school, Tyrese played a lot of basketball with friends, he noted. But as they all grew older, the friends started going to different schools and in different directions. “I started playing video games more and more, and then I eventually just stopped playing basketball,” he said.

Video games let Tyrese escape the stresses of socializing and making new friends. Already a little shy, he retreated more into the world on the video screen. Tyrese became skilled at gaming — adroitly manipulating avatars to victories against online opponents. All the while, his academic and personal skills atrophied.

The game changer that brought Tyrese back into the real world came during his sophomore year, 2020. That’s when Snider High School started an “esports” program. Esports is short for “electronic sports.” But it’s more than just “playing video games.”

Esports combines video gaming with organized team competition. That synergy is creating a whole new arena at middle schools, high schools and universities around the electrified world. It’s turned professional, too. Out of the competition come the intangibles — the esprit de corps — the pride in one’s school, in one’s teammates and in oneself.

Call it “esprit of esports”: Schools that have started esports programs are finding that esports fosters the same leadership, sportsmanship and communication skills traditional athletic programs strive to build. Students like Tyrese, who previously slipped through the cracks of athletics and other school activities, are now finding a place among their classmates and are engaged as never before.

“Tyrese is my favorite success story,” said Joseph Wilhelm, Snider High School’s esports adviser. “His story is kind of why we developed the program in the first place. He latched onto esports as a viable career path and college path and sees a goal.”

Since esports participation requires the same level of academic achievement as athletics and other extracurriculars, Tyrese found the motivation to attend classes and improve his grades. He’s now an A-B student. He is even planning to retake the classes he failed as a freshman to improve his GPA in hopes of achieving college admission.

Wilhelm says Tyrese is so highly skilled at Rocket League, one of the most popular games, he believes college esports scholarships will be in the offing for Tyrese when he graduates next month. “He was one of those kids who would never get to go to college if it weren’t for esports.”

From Pong To Present

Ever since the first pixelated Pong ball pinged across the primordial video screen a half-century ago, organized competitions have been a part of video game culture. While the complexity of the games, their graphics and storylines advanced light years over the next 30 years, competitions were mostly kept on an amateur level. That changed in the 2000s with the advent of livestreaming on the internet. Suddenly, the generation that grew up playing these games at home could also watch the best of the best compete. Video gaming became a professional sport with the surge in viewership. In 2018, the League of Legends World Championship, for example, brought in more viewers than the Super Bowl and the NCAA continued on next page continued from page 21

Final Four combined. In 2021, esports brought in more than $1 billion in revenue.

Today, the booming esports industry attracts 26.6 million monthly viewers who watch gamers compete in a vast array of virtual venues. Beyond games simulating real sports and traditional board games like chess, the online universe has expanded with fantastical strategy and battle arena games like Tyrese’s specialty, Rocket League, a kind of soccer played with rocket-powered cars. Even the International Olympic Committee (IOC) has been giving esports a look-see. In 2017, the IOC acknowledged the growing popularity of esports and said that competitive esports could be considered a sporting activity. While noting it was premature to make medal events for esports in the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris, the IOC has cited the need to keep the Olympics relevant to younger generations. Still, some esports-related activities might be part of Paris next year.

Beyond the pros on arena stages and online, esports has given rise to a whole host of career paths for professionals in marketing, information technology, programming, game and graphic design, and even broadcasting. Commentators who call the action occurring on the screen of esports events are called “shoutcasters.”

The growth of esports over the last two decades has brought a demand for extended opportunities for esports athletes. Universities across North America began offering scholarships to incoming freshmen to join their collegiate esports teams. In 2016, the National Association of Collegiate Esports (NACE) was founded as a nonprofit organized by its member schools to develop the framework for esports competition. Over 240 institutions with more than 5,000 student/athletes across the U.S. and Canada are members. NACE colleges and universities award an estimated $16 million a year in student esports scholarships and aid.

It Pays To Play

Just as collegiate esports has NACE, esports programs at Indiana secondary schools now have the Indiana Esports Network (IEN). Wilhelm, who was among the founding educators of IEN in 2019 and is now director, says the nonprofit organization functions like a state athletic association.

Indiana Esports Network is 100% volunteer driven and educator led, and its programs are free to students. Over 100 school districts across the state have joined the network. Wilhelm estimates over 1,500 Hoosier students are participating in esports programs the network coordinates and oversees.

Schools participating in esports run the gamut in size, demographics and socioeconomic populations — from big city schools like Ben Davis in Indianapolis to rural schools like Seeger Memorial Jr.-Sr. High in Warren County. Member schools include public, private and parochial.

Wilhelm said their statistics are showing that 80% of esports participants never participated in other school activities. “People understand why extracurriculars are important and the value of them, but they’re not reaching every student,” he said. “Our motivation here at Snider was to get students more motivated in school. We noticed a large portion of the student population wasn’t playing sports. They aren’t in band. They don’t really do anything extracurricular. They just come to school, go to their classes and go home. And for those students, there wasn’t a lot of extrinsic motivation for doing well.”

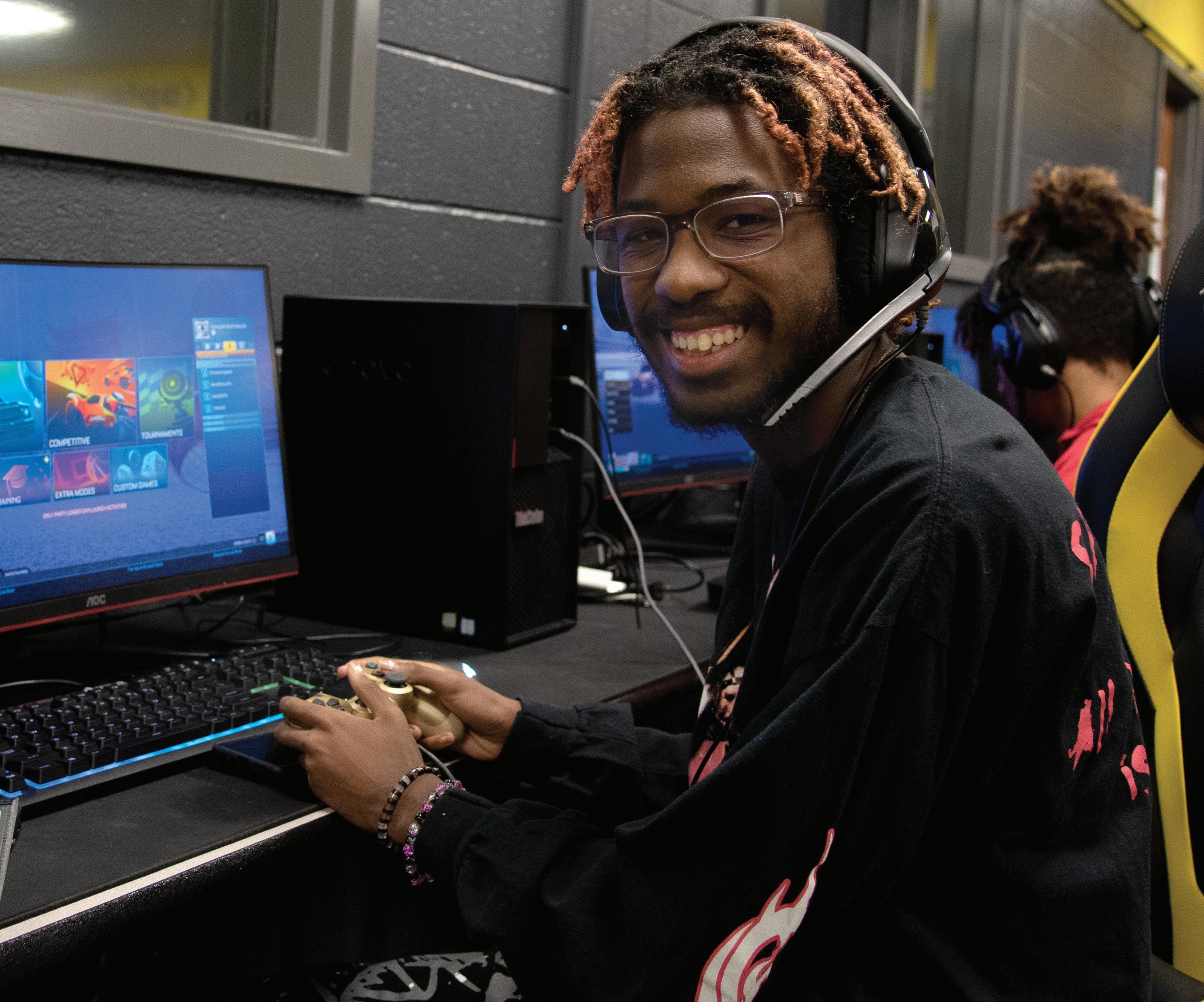

Today, Snider has about 80 students participating in esports. The esports game room, once a computer lab, is equipped with 20 single gaming stations and three large monitors with rows of game chairs. After school, the room is full of students interacting with the games and each other. Wilhelm admits that esports are still new to the academic environment, so it takes some convincing of administrators and parents — which requires facts and some tact.

“The initial comment is always like, ‘What? We’re trying to get our kids to stop playing video games.’

“Yeah, we get that,” Wilhelm tells them, and then comes the IEN pitch: “But let’s use it as a tool. Let’s control that and teach them healthy habits, as opposed to just what they’re doing at home. Let’s show how to do it in a productive way.”

Some of the valuable lessons that Wilhelm believes esports imparts to students include:

• COMMUNICATION. “We’re trying to focus on those soft skills that employers are looking for,” Wilhelm said. “And communication in teambased activities, being able to communicate clearly and effectively under higher stress or real-time situations is definitely useful.”

• TEAMWORK. “For some of them, it’s just the benefit of being part of a team where other people are depending upon them,” Wilhelm said. Sometimes students have never been in that team environment. “That sense of belonging and teamwork is impactful for a lot of our students.”

• LEADERSHIP. “Most all of our teams have in-game leaders, leading while the game’s happening. I think of it like your shot caller on the court or on the football field who’s actively making decisions. Putting students in leadership roles helps them develop that way, too.”

• SPORTSMANSHIP. “Video games have a stigma around them about how people interact online, of being toxic to faceless names on a computer.” Wilhelm said esports stresses sportsmanship and not talking smack. “What’s been super helpful, too, is having students meet their opponents in person at events, being able to put a face to this person online. And so, your actions online have real consequences when you tie that communication you’re having online to a real person.”

Wilhelm said there are also legitimate concerns about video game violence. He noted that in middle school and high school, esports includes games rated only “teen” and below. Some games do have simulated violence, he said, but they are all rated appropriate for teenagers.

Fortnite, for instance, is a popular game among teenagers. The goal is to eliminate other players. “But it’s very stylized. It’s akin to an animated cartoon,” he noted.

“It’s naive to think they aren’t playing these things,” he added. “But we say, ‘let’s teach them how to do it in a responsible way,’ as opposed to violence for the sake of violence.”

At the high school level, IEN currently organizes regular competitions for some 15 different games across three different divisions based on school size, in addition to middle school and unified competitions in conjunction with Special Olympics Indiana. Students at each school can compete at three levels: varsity, junior varsity and club. In addition to league/tournament administration, IEN provides support and training for coaches to assist their programs.

Right now, participating schools are gearing up for the in-person state IEN championship, which will be held at Ball State University April 29.

Leveling Up

LaGrange County REMC’s Operation Round Up (ORU) Fund committee hadn’t seen a grant request like the one Prairie Heights High School delivered in late December.

Cynthia Jones, an English teacher at Prairie Heights and the school’s grant writer, was asking for funds to help the school in eastern LaGrange County create a technology lab continued on next page continued from page 23 housing computers with specifications appropriate for graphic arts/website design — and esports gaming.

“Theirs was not a typical application,” said Nic Engle, marketing and public relations coordinator at the REMC and secretary of its ORU committee. “I don’t think we’ve ever had a request from a school for computer equipment for video gaming. But we have long supported youth athletics, dance teams and the like. With the increasing popularity of esports, the committee felt some funding to get them started with their own equipment would benefit a large number of students for years to come.”

Operation Round Up is a community program in which many electric cooperatives around Indiana and the nation participate. The fund is created by consumers who voluntarily allow their co-op to round up their electric bill each month to the next dollar. That amount, on average around 50 cents per consumer per month, is then pooled into a special account and dispersed for local charitable needs. LaGrange’s ORU committee awarded Prairie Heights $1,500 for the equipment.

Last fall, Jeremy Swander, the principal at Prairie Heights, heard the Indiana Association of School Principals (IASP) was initiating an “Esports Bowl,” akin to some of its traditional Spell Bowls and Quiz Bowls. Filling in as a teacher at the start of the school year, Swander asked his calculus class if anyone would be interested in starting an esports program. He got lots of questions, and ultimately 10 seniors participated.

For the pilot program, Jones said the school had to do a little begging and borrowing. The students brought in their own gaming systems from home, and the school’s FFA program loaned esports one of its presentation monitors. “We didn’t have any monitors that were new enough to connect to the gaming systems,” she said. “This was the makeshift way we’ve been doing it.”

Like Wilhelm, Jones saw how team play led to better engagement and collaboration during the pilot program in the fall. “It was set up through IASP that these guys could have joined in and competed from home. But they preferred to come to school and be here in person. They said it was better for them as a team. They communicated better, and they felt they would be more successful by being together in the same room versus trying to all play from home.”

The ORU grant, along with another from LIFE, LaGrange County’s youth philanthropy group, will allow the school to start purchasing monitors this spring. Jones said 27 students have expressed interest in being part of the esports program, which could begin as soon as the monitors arrive.

“The kids will still be bringing their gaming systems from home, but at least they won’t be bringing televisions on the bus.”

End Game

Tyrese Ellis still isn’t sure about his career plans. He said he’s thinking he’d like to become a nurse and maybe study Japanese. But one thing is certain that wasn’t four years ago: He’ll be able to graduate from high school next month and perhaps earn a scholarship to college.

As he and his two Rocket League teammates were about to sit down in the Snider esports room to an after school online match with a team from Elkhart County (which they later wrapped up quickly, winning 3 games to 0), Tyrese said, “I’ll always feel grateful and proud for being in here.“

Much like his Rocket League avatar shooting from one side of the arena to the other with a twitch of his finger, esports has changed the trajectory of where Tyrese’s life is pointing. “Everything really started changing my sophomore year. I started turning it around because of esports — because I had motivation.”

Richard G. Biever is senior editor of Indiana Connection.