47 minute read

Rich in Heritage

2016 McIntosh County Shouters, Photo by Dan Sheehy, Smithsonian Institution

February is recognized nationally as Black History Month. Here on the Georgia coast, this history is rich and varied. It encompasses traditions that can be traced back to West Africa, days of slavery in the plantation era, the unique culture developed here as part of the Gullah/Geechee Corridor, and growth beyond the segregation that prevailed in the South. It spans generations, incorporates tales of both triumph and tragedy, and there are endless stories that can be told. Visitors have come from far and wide to document the people, their practices, and the places that (continues)

make up this region. And this environment has also given birth to historians, storytellers, and fierce protectors and promoters of this very important cultural heritage. We’ve seen the voice of a people brought to life and carried through the years and across the miles from its roots in faraway lands.

Initially, slavery was prohibited in the colony of Georgia; however, that prohibition was lifted in 1750. Plantation owners sought out slaves from the coast of West Africa where rice, cotton, and indigo were native crops. Over the centuries that followed, the relative isolation of the African population brought here allowed them to recreate their native cultures and traditions on the coast of Georgia and the Carolinas, leading to the formation of an identity we now recognize as Gullah/ Geechee. In 2006, Congress designated the coastal region from Wilmington, North Carolina to Jacksonville, Florida as the Gullah/ Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor, saying “it is home to one of America’s most unique cultures, a tradition first shaped by captive Africans brought to the southern United States from West Africa and continued in later generations by their descendants.” This culture encompasses language and oral history, music and dance, spirituality, food, and distinctive arts and crafts like sweetgrass basket weaving.

The art of sweetgrass basket weaving is practiced in the Gullah/Geechee Culture Heritage Corridor that spans from the coastal and barrier island communities from North Carolina to Florida. You can find basket weavers here on St. Simons Island, on Sapelo Island and in McIntosh County. The beautiful baskets are each created with a knot to start and then grasses are repeatedly coiled and wrapped with strips of palm frond stems. Many have ornate designs, some have handles and/or lids. They were traditionally used for storing food, fanning rice and bringing crops in from the fields, among other practical purposes, but now are considered by many to be collectible works of art.

It was in attempting to capture and catalog this unique heritage that stories were discovered. Lorenzo Dow Turner, the Chair of African Studies at Roosevelt University and a leading English scholar, was one of the first to investigate and record the Gullah language, a true African American Creole dialect. Turner interviewed Harrington resident Belle Murray as part of his research for Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect. He also recorded several songs for Lydia Parrish, wife of artist Maxfield Parrish, and a part-time resident of St. Simons Island who began a collection of slave and folk songs after hearing her housekeeper, Julia Armstrong, sing. Parrish visited former plantations asking someone at each one to sing the “old songs.” In the 1920s, she organized the Spiritual Singers Society of Coastal Georgia primarily to perform at The Cloister at Sea Island. She later wrote the book, Slave Songs of the Georgia Sea Islands, which remains a definitive work on the subject. The Spiritual Singers Society of Coastal Georgia would later evolve into the Sea Island Singers and catch the attention of folklorist, musicologist, and field collector of folk music Alan Lomax while he was visiting St. Simons Island in 1935. And it is in the music and dance, that we find more stories to be told.

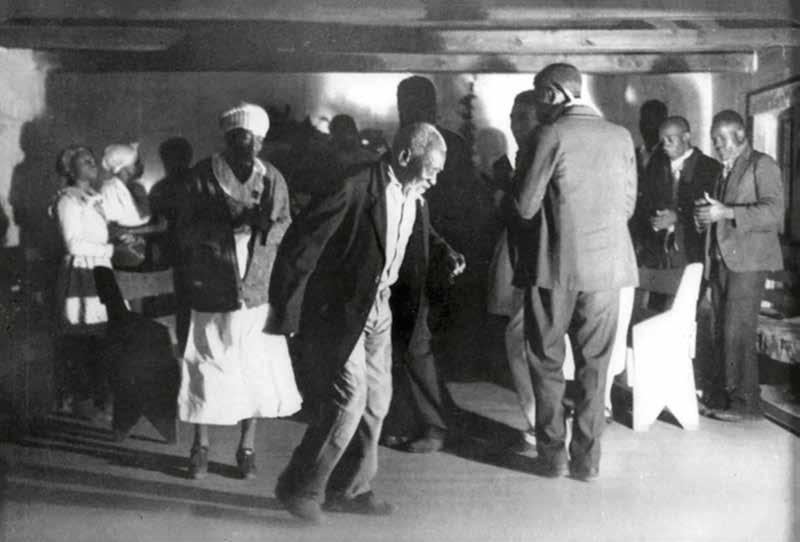

Ring Shouters on St. Simons Island, 1930s.

In the beginning, there is the beat.

Adistinctive clapping of the hands and tapping of the feet. As a broom stick joins in and pounds out the rhythm on the hardwood floor, the dancers begin to move. They move to the beat in a slow counterclockwise manner; shuffling along, their feet never leaving the floor, heels keeping time with bent legs always moving forward, never crossing, circling slowly to the beat. Then a voice is heard. A voice that, although carrying a tune, is not really singing and not really talking either, but speaking to the beat:

Oh Eve – where is Ad-u-m? Oh Eve – Adam in the garden.

A chorus answers:

Pinnin’ Leaves. Pinnin’ Leaves. Adam in the garden. Pinnin’ Leaves. Pinnin’ Leaves.

by Mason Stewart

Thus, begins the ring shout, a unique demonstration of both performance art and living history. Performance art because it is a carefully choregraphed cultural dance performance of the highest caliber. Living history because it is the oldest surviving African American performance tradition in North America.

The Gullah Geechee language featured in the songs grew out of the isolation of (continues)

the enslaved Africans who toiled in fields on the plantations scattered amongst the lowlands and barrier islands of the coastal South. However, many of the rhythms and dance steps performed trace their origins even further back into the now long-forgotten past before the middle passage, to the imagined halcyon days of freedom in West Africa. Due to its own unique nature and isolation, this performance art and living history was almost lost forever. Fortunately, thanks to the tireless efforts of a few who grasped its cultural significance and took the time to preserve its history, the authentic performance continues.

The tempo of the beat increases. As the dancers move, shuffle, and sway to the beat, they fill their aprons with imaginary leaves and the songster sings out:

Lord called Adam.

Pinnin’ Leaves. Pinnin’ Leaves. Adam wouldn’ answer.

Pinnin’ Leaves. Pinnin’ Leaves. Adam Shame’

Though some of the highly-stylized movements may owe their true origins to older Muslim or African tribal ceremonial traditions, historians assert that the ring shout itself is a completely original African American art form. It is a unique cultural expression that grew out of an enslaved people’s exposure to the teachings of colonial Christianity. Not the redemptive Christianity that was practiced by their masters, but a Christianity viewed through the eyes of those who – robbed of everything else – yearned for the promised freedom of a joyous hereafter. So, as the performance continues, each ring shout tells its own unique story, ever expanding on those early traditions.

Now the Shouters sing out:

Come t’ tell you ‘bout Jubile A-a-ah my Lord! My Mother done gone to Jubilee My soul rock on Jubilee! I got a right in Jubilee I got a right in Jubilee This time, they are not just performing a quaint traditional slave song of the Georgia Sea Islands, but are also, on a much deeper level, sharing the soul of an enslaved people. And though the infectious joy of the double-time beat captures the moment and invades the feet, for those who truly listen, the words carry a solemn melancholy plea that also tugs long and hard at the heart.

According to historians, the beginnings of the ring shout as we know it today, probably began as two separate art forms: the shout and ring play. The shout was a purely religious “call and response” technique adopted by (continues)

African American preachers to teach and spread the new religion. Being predominantly Protestant, the new religion of the enslaved Africans did not include the sin of dancing, which was officially discouraged. However, secular ring play, which involved both singing and dancing, was also popular at the time and had very strong cultural roots. The rhythmic patterns of ring play fit naturally into the equally rhythmic religious call and response tropes of the day. As long as the content was religious in nature, and the moves did not involve sinful dance steps like toe tapping, crossing of the legs, or fiddle playing, the merging of the two art forms began to arise as an acceptable form of religious expression. And that is likely how the ring shout was born.

One historian noted that, “During slavery, the ring shout was practiced more during the holidays between Christmas and Watch Night [New Year’s Eve]. It was during this week when they had more time to be with family.” It was a celebration of watching the old year leave and the new one arrive. It was a time filled with thoughts of hope and enlightenment. People would go from house to house and shout. “Sometimes when the shouting got really excited, the floors would fall apart from the beating of the stick and the men would end up repairing them the next day.”

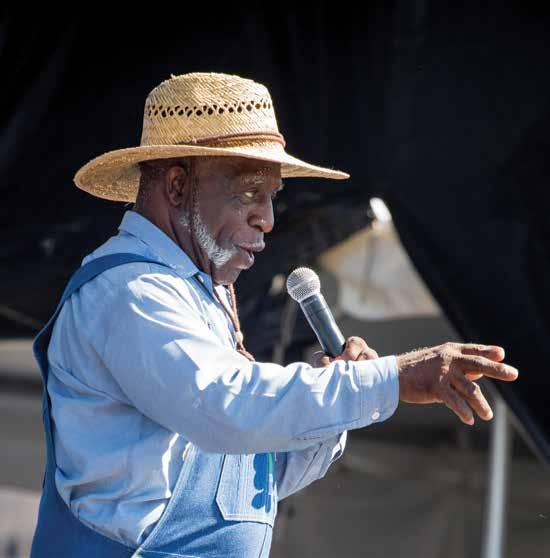

Though performance variations of the ring shout existed among the many isolated plantations throughout the Southeast, the basic elements of the shout were the same. According to Venus McIver of the McIntosh County Shouters, “The shout we were taught as children was very specific. Our parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents were very particular. If you didn’t shout correctly, you couldn’t shout with the ‘old folk’ yet. But you could shout with the other children until you got it right.” As such, the ring shout spread as an integral part of the religious and cultural life of the enslaved African Americans of the coastal South. And many sang a variation of:

Want t’ go t’ Heaven got t’ plumb de line. You got t’ Shout right. Plumb de line You got t’ Shout right Plumb de line Want t’ go t’ Heaven got t’ plumb de line. not part of the pure ring shout tradition, their impact on African American plantation life was nevertheless significant and lasting. You can see how they ultimately made their way into the performance art seen today in secular songs like:

ABOVE LEFT: Georgia Sea Island Singers perform at the Reflecting Pool, Washington D.C. during the Poor People Campaign May, 1968. RIGHT: McIntosh County Shouters performing at the Freedom for Sounds festival celebrating the grand opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., 2016, Jason Thrasher, Thrasher Photography.

Once I went out huntin I heard de possum sneeze I holler back to Susan Put on de pot o’ peas

The obviously non-religious dance step, known as “The Buzzard Lope” is now a popular part of the performance tradition and is often demonstrated by Frankie Quimby of the Georgia Sea Island Singers and Griffin Lotson of the Geechee Gullah Shouters.

Along with secular dancing, some African drum routines, once strictly forbidden, have also reappeared in modern performances. African drums were outlawed on most (continues)

plantations because the slave owners believed they could be used as secret communication devices by their slaves to plan escape, or even worse, insurrection. In response to the ban, the enslaved African Americans invented an entirely new rhythm technique called “hamboning” or “Juba Dance,” using foot stomping and hand slapping of the chest, legs, hands, cheeks, etc. to keep time and replicate their earlier forbidden drum rhythms.

Hambone, Hambone Where you been? ’Round the corner And back agin’ Hambone Hambone Where’s your wife? In the kitchen cookin’ rice

National recognition of groups that performed slave spirituals, work songs, and ring shouts began after Bessie Jones caught the attention of Smithsonian Institution folklorist Alan Lomax, who had originally seen the Sea Island Singers in 1935 when he was visiting St. Simons Island. In 1959, he returned to the area and was impressed by Bessie Jones’ contribution to the group with her strong vocals. He made field recordings of the Georgia Sea Island Singers in 1959-60. These recordings are now part of the Library of Congress. He also recorded Bessie while working on her biography in New York in 1961. Since that time, the Sea Island Singers with longtime member Frankie Quimby have performed for three presidents, at two Olympic Games, and various other events and festivals throughout the years. In 1990, they received the Governor’s Award in the Humanities. The Georgia Sea Island Singers were one of the most popular groups on the folk circuit in the 1960s and 70s. Then, as pervasive as this African American tradition was, it began to slowly disappear. According to ring shout practitioner and historian, Griffin Lotson of the Geechee Gullah Shouters, a major reason was that after the Civil War, the formally isolated African Americans of the rural South began to interact with the more urban and “sophisticated” communities of the North and began to abandon their traditional Gullah Geechee heritage. The old ways were viewed by many as too provincial or countrified, so the unique traditions and practices that once defined a people fell into disuse and, except for a few isolated areas like around the Sea Islands of the Georgia coast, began to disappear.

May be the las’ time we shout together May be the las’ time I don’t know May be the las’ time we shout together May be the las’ time I don’t know I don’t know, I don’t know, may be the las’ time, I don’t know

Just how close did this fundamental African American art form come to disappearing completely from history? In 1983, Doug and Frankie Quimby, prominent and renowned members of the Georgia Sea Island Singers asked writer, artist, and photographer Fred C. Fussell and Southern Music Scholar, George Mitchell, to help locate new participants for the Georgia Sea Island Festival. According to Mr. Fussell, the only surviving ring shout group they found, “not just on the Georgia/South Carolina coast, but anywhere in the country” was at the Mt. Calvary Baptist Church in the small community of Bolden, near Darien, Georgia.

This group, known now as the McIntosh County Shouters, somehow managed to resist the cultural eraser that freedom and modernity often brought to so many other formerly enslaved communities. Perhaps it was due to their relative isolation from the assimilation pressures of big cities, or maybe it was also due to the extraordinarily close knit family bonds of the community itself. This may have started with their ancestors, Amie and London Jenkins, who were split up during the Civil War and sent to different plantations. However, once they were told they were free, they set out on foot to reunite with one another. Since then, the family has grown and remained very close; passing down from generation to generation a proud heritage based on a strong tradition of family, faith, and community. For whatever the reason, standing at the center of that special heritage is the ring shout and (continues)

Geechee Gullah Shouters. Photo by Paul Meacham @ CoastalGATravel

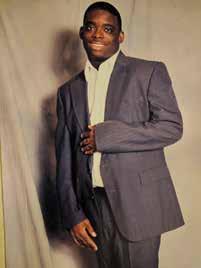

On December 10, 2016, Christopher Daunté Walcott, one of the younger members of the McIntosh County Shouters’ family, passed away from heart failure. Vanessa Carter, the group’s narrator, was Christopher’s mother. His aunt, Carla Jordan, and grandmother, Carletha Sullivan, are Shouters. Christopher was related to everyone in the group in one way or another as this group is all family.

As the son of career Army parents, he lived in various places around the world: Hinesville, GA; Vicenza, Italy; Tacoma, WA; Atlanta, GA. He was active in Boy Scouts and played basketball, football, and soccer. He also participated in and won many dance competitions. While living at Ft. Lewis in Washington State, he performed in several musicals in local theatres in Tacoma and Seattle. In 1994, he was appointed Conflict Manager of the Tacoma Public School System. The following year, Chris began pursuing a career in acting and auditioned for, and was cast in the Broadway musical Showboat at the Paramount Theatre in Seattle. In 2003, he campaigned for and was elected President of the 11th District Young People Department General Missionary Baptist Convention of Georgia, Inc. as a member of Mt. Calvary Baptist Church. He graduated from Liberty County High School in Hinesville, Georgia in 2005, and attended college at Ogeechee Tech in Statesboro, Georgia. His life was short on this plane but his memory will never be forgotten in this family.

the traditions carried on for generations by the Mt. Calvary Baptist Church and the McIntosh County Shouters.

Today, thanks to a renewed interest in preserving, protecting, and promoting our vanishing cultural history, Southeast Georgia ring shout groups – far from vanishing – have not only survived, but gained national fame and international recognition. The McIntosh County Shouters were the recipients of a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1993 and received a Governor’s Award in the Humanities in 2010. Last September, they were given the high honor of being invited by the Smithsonian Institution to perform in celebration of the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. They have also participated in shows at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, the Library of Congress, and at countless festivals and events throughout the United States. They have been featured in a Georgia Public Television documentary and on a Folkways LP. The “newest” of these groups, the Geechee Gullah Ring Shouters, was formed in 1992 with the overall goal of preserving and protecting the unique and precious Gullah Geechee heritage. The reverential and spiritual nature of the shout earned the Geechee Gullah Ring Shouters an invitation to perform at the pre-papal Mass during Pope Francis’ 2015 visit to Philadelphia.

So, the next time you hear the clapping of the hands and the tapping of the feet, or the sound of a broom handle pounding out the beat, pause, listen, and then join in with:

My soul rock on Jubilee! O-o-oh my Lord! That Jub!, That Jub! That Jubilee! My soul rock on Jubilee!

And become part of a living history that persevered to provide the cultural foundation for so much of what we call American music today.

Historian and Executive Director of the St. Simons African American Coalition Amy Lotson Roberts remembers those days when Alan Lomax came and interviewed Bessie Jones over at the church over on George Lotson Ave and Jordan Ave. She recalls him taking the Georgia Sea Island Singers to Virginia to perform. They were sharing “the old ways. Always the old ways,” she says. Amy too shares the old ways, by telling her stories and educating people about the African American culture on the island. She was instrumental as a director of the Georgia Sea Islands Festival, which began in 1978 and will return again to Gascoigne Park again this June. And while she understands the cultural significance of the shout in coastal Georgia musical heritage, it certainly wasn’t the only music that was happening here when she grew up. Far from it! (continues)

Those were the days of the juke joints. Not night clubs or dance clubs, she clarifies, but “juke joints.” Some were also eateries, but others were solely for drinking and dancing. There was the Atlantic Inn on Demere that was owned by Earl Hall. There was the Melody Lounge, also on Demere. Then down off Arnold, there was The Savoy, The Pig, which also had a restaurant, and The Shoe Shop. Hazel opened her café down there about the same time. She had worked for the shipyard and when they shut down, she and her siblings opened the restaurant to feed the folks who stayed in the rooming houses on the south end. The Blue Inn and The Tropadero were juke joints further up the

island. While Amy claims to be too young to have frequented these drinking and dancing establishments, she remembers Chick Morrison bringing musicians down to play, and how they’d stay at his mother’s yellow cottage because there were no hotels or motels open to blacks. She recalls B.B. King being a visitor, as well as others. There were also little washboard bands that used to play out at Sea Island a lot. “There was something going on every weekend,” she shares.

Over on the mainland, black entertainers on the “Chitlin Circuit” would perform at the multi-purpose building/gymnasium at Selden Park. The Selden Normal and Industrial Institute opened in Brunswick in 1903 and was considered one of the finest black educational facilities of its time. Known for its pioneering attempts in intermediate education of the black community in Coastal Georgia, it closed in 1933, and later became a public park. Around 1950, the park became a recreational area for blacks due to their lack of access to other parks and beaches because of segregation. It was a perfect stop for black performers on the “Chitlin Circuit.” Shows that took place at Selden included Otis Redding, James Brown, Cab Calloway, Junior Walker, Al Green, Sam Cooke, Moms Mabley, Shirley Caeser and others. From blues to gospel to Golden Gloves boxing events, Selden was a central hub of entertainment in the black community.

Another school near and dear to Amy’s heart and the focus of her recent preservation efforts is the Harrington School on St. Simons Island. It was the site of many of the historic moments and meetings referenced previously and represented freedom to a Gullah Geechee community. (continues)

TOP: Douglas Quimby and Bessie Jones participate in a Folk Artist in Residence program at California State University, Fresno, in 1977. Photo courtesy Evo Bluestein. LEFT: Amy Roberts, Executive Director of St. Simons African American Heritage Coalition. Paul Meacham @ CoastalGATravel

“Three things struck me in quick succession when I was boosted up and through the stairless back door of the old schoolhouse on South

Harrington Road,” recalled Patty

Deveau, president of the Friends of Harrington School. “First, this looked like a Rosenwald school.

Second, it was still standing because education meant freedom in a Gullah

Geechee community. And third, I did not fall through the floor.”

The last was most important to Deveau because if the floor was this solid, it could mean that the schoolhouse was not “beyond repair” as generally assumed and the St. Simons Land Trust (SSLT) and Glynn County might allow the St. Simons African American Heritage Coalition (SSAAHC) to get a second opinion so that the last African American schoolhouse on St. Simons Island could be saved and restored.

Fortunately, that permission was granted and the SSLT and the County, who jointly owned the schoolhouse, agreed to put the demolition permit on hold. The Historic Preservation Task Force of the Coastal Regional Commission reported that although there was termite and storm damage to the building, the foundation beams were solid and the schoolhouse had been so well built that “it could float.” The SSAAHC received a 99-year lease from the SSLT to restore, maintain and operate the historic schoolhouse. The Friends of (continues)

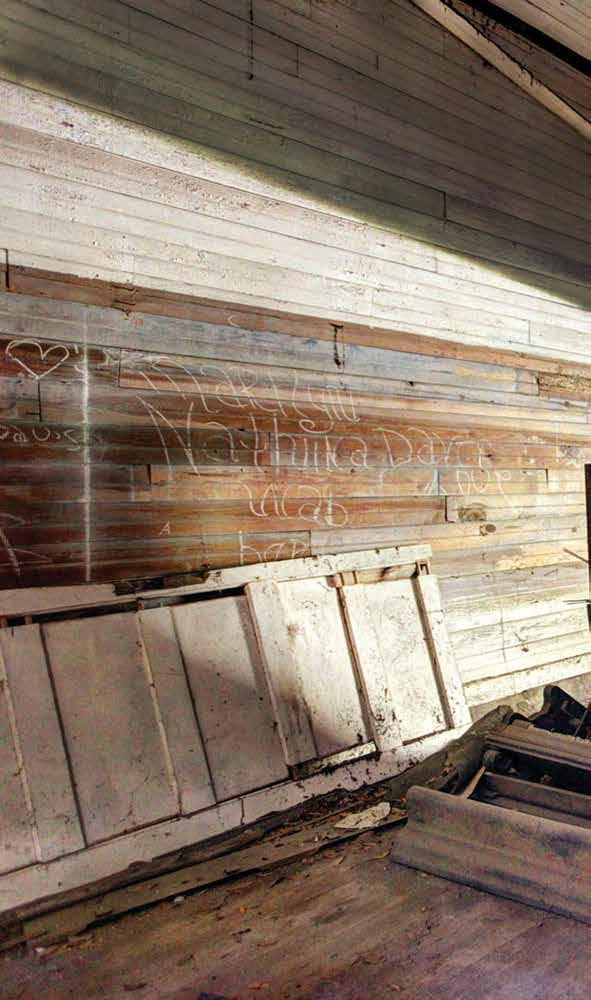

HARRINGTON SCHOOL PHOTOGRAPHS BY BENJAMIN GALLAND, H20 CREATIVE GROUP

An upright piano lay in ruin before plans to save the Harrington School were started.

GOLDEN ISLES ANIMAL HOSPITAL

You clean your teeth, let us clean theirs

Monday-Friday, 7:30 a.m. to 6 p.m. Saturday 9 a.m. to 12 noon

9 Glynn Avenue Brunswick 912.267.6002

goldenislesanimalhospital.com

Schedule your pet’s dental screenings within three weeks of their exam and get a $50 credit towards the dental procedure.

Harrington, Inc. was formed to assist the SSAAHC with restoring the historic Harrington school.

It turns out that an historic structure restoration isn’t done in a day. Or even a year or two. But it does happen with excellent professional advice, mostly good weather, generous donors, and a persistent band of optimist volunteers. Those folks will be celebrated at the annual Friends of Harrington lunch meeting on Saturday, February 4 at 11:00 a.m. at Bennie’s Red Barn. (The public is invited. For more details and to R.S.V.P, visit ssiheritagecoalition.org.)

Between 1917 and 1932 over 5,000 schools were built for African American children across the South through a collaboration between Sears CEO Julius Rosenwald in Chicago and Tuskegee University President Booker T. Washington. “The Rosenwald Fund drew up the school plans and offered grants to local communities to build a school if the local African American community and the local public officials would raise about two-thirds of the necessary funds, and provide the local materials and skilled labor to build the school. Deveau recognized the schoolhouse design immediately because as a coastal historian and historic preservationist she was aware that both the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Georgia State Historic Preservation Office had initiatives to locate and document these schools. “While no record had been found that Harrington was funded by the Rosenwald Fund,” Deveau pointed out, “the school dimensions right down to the measurements for the blackboards for younger children and older students mirror the exact specifications for the Rosenwald Community School Plan A.” Shortly after taking that first step inside the old schoolhouse, Deveau went to the special collections section at the Brunswick library and found a 1920 U.S. Bureau of Education Report on Glynn County schools that made a reference to the need for two Rosenwald schools on St. Simons Island, or, the report read, “if you cannot build a Rosenwald, build a similar plan.” That school, she is convinced, is Harrington.

The Harrington Graded School was built in the 1920s by African American tradesmen for the education of their children and grandchildren. Each nail in this simple one room structure held the future for those descended from slaves who worked the island’s cotton and rice plantations. “Education meant freedom in our community,” said Emory Rooks, SSAAHC treasurer, former Harrington student and descendant of the Cannon Point slave/driver Salih Bilali. Rooks reminded the volunteers that anything they needed to do to this historic structure had to honor that legacy and be good for another 99 years or so. The Friends of Harrington and SSAAHC pulled together a statewide Historic Preservation Technical Advisory Committee to review and approve each step and a local board of former students, historians, and community elders to follow the work. The SSAAHC selected Hansen Architects and Tidewater Preservation, both firms with excellent experience and a vast amount of patience. Work progressed only as funds were raised.

The details of the restoration: the plans, progress, historical programs, and fundraising events, can be found on the coalition’s website. “We wanted to keep our members and the public informed throughout the restoration,” stated Natalie Moore, SSAAHC president. Their first event, “Architectural Archeology Day,” provided an inside look at the schoolhouse and helped supporters see for themselves what work needed to be done. Best of all, Deveau remembers all the former students who came to the schoolhouse to tell the contractors and guests what details they remembered about the school building. “We have a video of Mrs. Isadora Hunter who attended the school in 1928 giving preservation contractor Greg Jacobs a tour of her schoolhouse. It was a cold rainy day but Mrs. Hunter, age 90, came out in her hat, gloves, matching purse and perfectly tailored wool skirt,” Deveau reminisced. In 2004, Mrs. Hunter donated her portion of her inherited

property so that the schoolhouse along with surrounding 12 acres could be preserved. The Harrington Community Park with trails and ponds opened in December 2016.

Nearly $300,000 was raised over seven years to restore the schoolhouse. Initial grassroots support stabilized the structure and put on a new roof. Larger donations boosted the smaller grassroots gifts to replace the asbestos siding, repair walls and foundations, repair windows and doors, and paint the exterior. The recent challenge grant from the Watson Brown Foundation encouraged donors to double their gift impact before the end of 2016. Currently the final interior tasks are being completed and supporters anticipate the schoolhouse to open within the month.

Many donors made gifts in honor of persons who taught them the most. A young woman from Cajun Louisiana recognized “Miss Rose” who gave her encouragement to become a teacher at a time and place when girls were supposed to quit school, marry young, and (continues)

Love yourself … Love your teeth … We can help save them

We are in network with many insurances and are happy to give estimates over the phone. Emergency pain patients accepted at any of our 3 locations. 1804 Frederica Rd., Suite B St. Simons Island 912.268.2800 www.coastalendo.net

SPRING IS JUST AROUND THE CORNER! Free Delivery & Set-Up

Come see us at The Patio Store!

Otis & Susan Lee, owners

LARGE DISCOUNTS

ON A WIDE VARIETY OF FLOOR MODELS

BRANDS WE CARRY: Breezesta, Chicago Wicker, Erwin & Sons Wicker, Lloyd Flanders, Tropitone, Windham Castings, Castelle, Casual Line PVC, Oriflamme Fire Tables, Treasure Garden Umbrellas, Royal Teak, Windward Design Group

Located 1.7 miles East of I95 at exit 3 in the Three Palms Plaza in Kingsland. Open Tuesday – Saturday (912) 729-1173 thepatiostorega.com

have lots of babies. One man honored Charlie Hunter and Tom Ramsey who always took him and his brothers coon hunting and digging for oysters. One son honored his parents who were teachers at South End School. Another student thanked her Harrington teachers Mr. and Mrs. Johnson. Another former Harrington student, now a retired colonel, remembered his grandfather a local pastor. A lady who chose St. Simons Island as her second home was honored after her death by her friends and colleagues who recalled the consortium she founded for over 100 storeowners across the nation devoted to children. All donors are listed on the Honor Roll and their Tributes to Teachers can be found on the coalition’s website.

While restoring the historic structure the SSAAHC and Friends of Harrington held events that also fulfilled the SSAAHC mission “to educate, preserve and revitalize African American heritage.” Eight former students told an audience at Coastal Georgia Historical Society about the lessons they were taught and lessons they learned in their one room segregated schoolhouse and in the boarding schools they attended after Glynn County consolidated public schools and closed Harrington. An audience of “snowbirds” at Jekyll Island Museum eagerly asked questions about what it was like to live during segregation. Service Learning students at the College of Coastal Georgia prepared biographies of the persons whose names appear on the street signs in the island’s African American neighborhoods. For three years Mercer University students created video essays from oral histories they held with community elders. SSAAHC Executive Director Amy Lotson Roberts has been collecting photos and funeral programs from community families as well as conducting tours of the island’s African American historic sites. “Most coastal historical sites focus on slavery. We want to complete the history of our area by filling in the 150 years from emancipation through the civil rights era,” summarized Roberts who received the 2012 Georgia Governor’s Award in the Humanities for her work saving and sharing local African American history.

When opened The Historic Harrington School Cultural Center will once more be a place for education and community gatherings. The building will be used for educational interpretation about the site and its Gullah Geechee history. The building will be “divided” into two sections. One section will have a gift shop with items for sale, a display of various artifacts, and bookshelves filled with a library of local history resources. The second section will be a classroom for classes about history, traditional cooking, quilting, weaving, and various musical instruments. Also, the school will be used for meetings, to host gatherings, reunions and community events. Guidelines will be developed for its use and will be available from SSAAHC on their website: ssiheritagecoalition.org. The schoolhouse will once again be providing lessons to a whole new generation.

The SSAAHC is seeking sponsors, partners and volunteers to assist them in 2017. Volunteers can help save and share local African American history in many ways: tours, special programs, collecting and organizing archival material and oral histories, and expanding membership. There will be sign-up sheets and more details at the February 4 meeting and on the website. SSAAHC president Moore said that “If you like music and enjoyed last February’s tribute to Bessie Jones, Frankie Quimby and the Georgia Sea Island Singers, help us plan three upcoming events: Motown Revue in April; a Musical Extravaganza in early June that will recall the big bands and headliner performers who visited local juke joints traveling between gigs in NYC and Miami, or attend the June 3 Georgia Sea Island Festival which has been highlighting traditional music, crafts and food for more than 30 years.” For more info, call 912.634.0330 or email friends@ssiheritagecoalition.org.

Through the St. Simons Island African American Heritage Coalition, Amy Roberts conducts tours on St. Simons Island of secular and non-secular sites significant in African American heritage on the island. The old cemeteries and memorial statues are among some of her stops. A guided tour of the island with her vast knowledge is highly educational. A few significant memorial sites in the Golden Isles are worth noting (continues)

here, but for a comprehensive view of African American life on the island, take the tour.

At Fort Frederica, there is the Abbott Memorial that was erected by Robert Sengstacke Abbott. Born in 1868 on St. Simons Island to former slave parents, Abbott studied printing at Hampton Institute in Virginia and in 1898, received his law degree from Kent College of Law in Chicago. Because of racial prejudice, he found himself unable to practice despite attempts to establish law offices in Illinois, Indiana, and Kansas. In 1905, with an initial investment of only 25 cents, he founded the Chicago Defender. The publication was at one time heralded as “The World’s Greatest Weekly” and was one of the most widely circulated black newspapers in the country. Abbott established himself as one of the first self-made millionaires of African American heritage. He returned to St. Simons Island in the 1930s and erected a memorial statue honoring his father Thomas Abbott and his aunts Celia Abbott and Mary Abbott Finnick on the grounds of Fort Frederica. Robert Abbott died in 1940. The Robert S. Abbott Award was established in memory of the late founder of the Chicago Defender and was given to “the person or organization which in the preceding year has done most to advance the cause of American democracy.” Recipients have included President Harry S. Truman, President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Thurgood Marshall.

In the Village on St. Simons Island, you’ll find Neptune Park and a memorial plaque by the flagpole near the entrance to the pier discussing the life of Neptune (given the last name Small because he was a diminutive man) and his service to the King family of Retreat Plantation. He is best known for his loyalty to his masters, as he brought the body of Henry Lord Page King back to Savannah from Virginia when he was fatally wounded in the Civil War. He then returned to serve another King son in the war, and was freed and given a tract of land by the King Family. He died in 1907 and was buried in the Old Retreat Burying Ground. Neptune Park in the Village on St. Simons Island is named in his honor.

In the St. Andrews Picnic Area on the south end of Jekyll Island, there is a memorial that commemorates an audacious act that was intended to spark a civil war: the arrival of The Wanderer. Owned by Charleston resident William Corrie, The Wanderer was a racing schooner that he had equipped as a slave ship to transport approximately 400 slaves illegally imported from the west coast of Africa to Jekyll Island. This shipment of human cargo is one of the last known groups of enslaved Africans sold into slavery in the United States. The ship was later seized by the Union Army and used for supply and dispatch. After the war, she was used in the West Indian fruit trade until she sank in Cuba in 1871. The memorial was erected on Jekyll Island in dedication to the slaves carried aboard that ship.

Although no historical marker exists to denote Ebo (or Igbo) Landing, it is no less significant in terms of black history and an identity that shaped the culture of the people here. This location on St. Simons Island at Dunbar Creek was the site of a rebellion and mass suicide of Igbo tribesmen in 1803. About 75 Igbo tribe members, who were taken from what is now known as Nigeria, were transported to Savannah, where they had been sold into slavery to John Couper and Thomas Spalding. The chained slaves were then loaded on board a smaller vessel to travel to St. Simons Island. During the course of the journey, they rebelled against the white agents, taking control of the ship and drowning their captors. The boat was grounded in Dunbar Creek, where the slaves then marched into the water after their chief, preferring death to slavery. At least 13 bodies of drowned slaves were recovered. The number of deaths was uncertain. It has been reported that survivors were taken to Cannon’s Point and to Sapelo Island. (continues)

Robert Abbott

COSMETIC & FAMILY DENTISTRY

Highly Recommended. Highly Referred. Accepting New Patients.

912.638.9946 300 Main St. #102 bryandentalssi.com

“Chocolate Plantation, on the north end of Sapelo, is quite a compound, once representing a population of approximately 100 people from 18 households. Only the barn remains standing today. I knew that a photo from ground-level wouldn’t capture the magnitude of the layout, so equipped with my drone, I set out to capture one of the only published aerial photographs of Chocolate Plantation.” – Benjamin Galland

Many here can trace ancestry back to Bilali, a slave and overseer for Thomas Spalding on Sapelo Island from the Sierra Leone area who was highly valued as a master cultivator of rice. According to scholars who interviewed Bilali, he was born around 1770 to a well-educated African Muslim family, enslaved as a teen and taken to the Caribbean. There, he was purchased by a Dr. Bell, and worked as a slave at his plantation for 10 years, before he was sold to a trader in 1802 and transported to Georgia. In Georgia, he was purchased by Thomas Spalding of Sapelo Island. Bilali spoke Arabic and knew the Qur’an. An Arabic manuscript Bilali had written was discovered upon his death in 1857 and is held at the University of Georgia in the Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Cornelia Bailey is a descendant and discusses Bilali in her well-known 2000 book, God, Dr. Buzzard and The Bolito Man.

A member of the last generation of African Americans born and educated on Sapelo Island and a self-proclaimed “Saltwater Geechee,” Cornelia Bailey has Cornelia been hailed as one Bailey of the most vocal defenders and of her barrier island homeland and its cultural heritage. She was born on Sapelo in 1945 and her published memoirs, God, Dr. Buzzard, and the Bolito Man, has been relied upon heavily for its accounts of history and Geechee (continues)

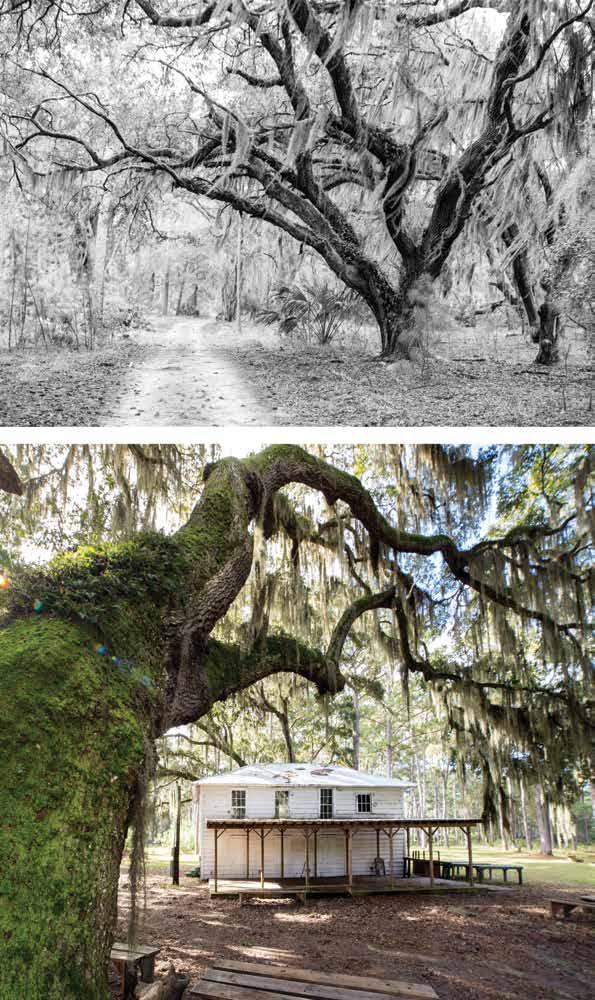

“The island is a pristine example of a maritime forest habitat. Infrared

Film photography has always been a passion of mine and

I’ve incorporated several shots from this medium in the book.

I feel the contrast it creates adds to the final mood of a photograph.”

“One of the oldest remaining buildings in Sapelo Island’s

Hog Hammock community, the

Farmers’ Alliance

Hall was built in 1929 with salvaged wood from an old oyster factory. For me, framing the shot with the towering ancient oak in the foreground was instrumental in enhancing the depiction of the heritage and historical value here.” heritage and culture on Sapelo Island. In the book, she talks about growing up on Salepo Island in the 1940s-50s, shares childhood stories and family legends passed down through generations, and creates a vivid picture of the African American culture that emerged on the island more than 200 years before. She is considered the “griot,” or tribal historian for the Geechee culture on Sapelo. Living in the Hog Hammock area of the island, Bailey has spent years as a tour guide, public speaker, educator, and writer helping to raise awareness about the threat of industrial development to the community’s cultural heritage and rich history. She received a Governor’s Award in the Humanities for her work in May 2014.

On these pages, photographer Ben Galland shared with us a “behind-the-scenes” look at the magical world of Sapelo.

If you’d like to learn more about Sapelo Island and the Geechee culture, this spring is the perfect time. Because of the success of their inaugural series last year, the Coastal Georgia Historical Society is presenting a second annual Journeys program which will again combine an educational program with an expert-led field trip. This year, they plan to launch an exploration of Georgia’s barrier islands and the first stop is Sapelo Island. On Thursday, March 23, Coastal Georgia historian Buddy Sullivan will unveil his (continues)

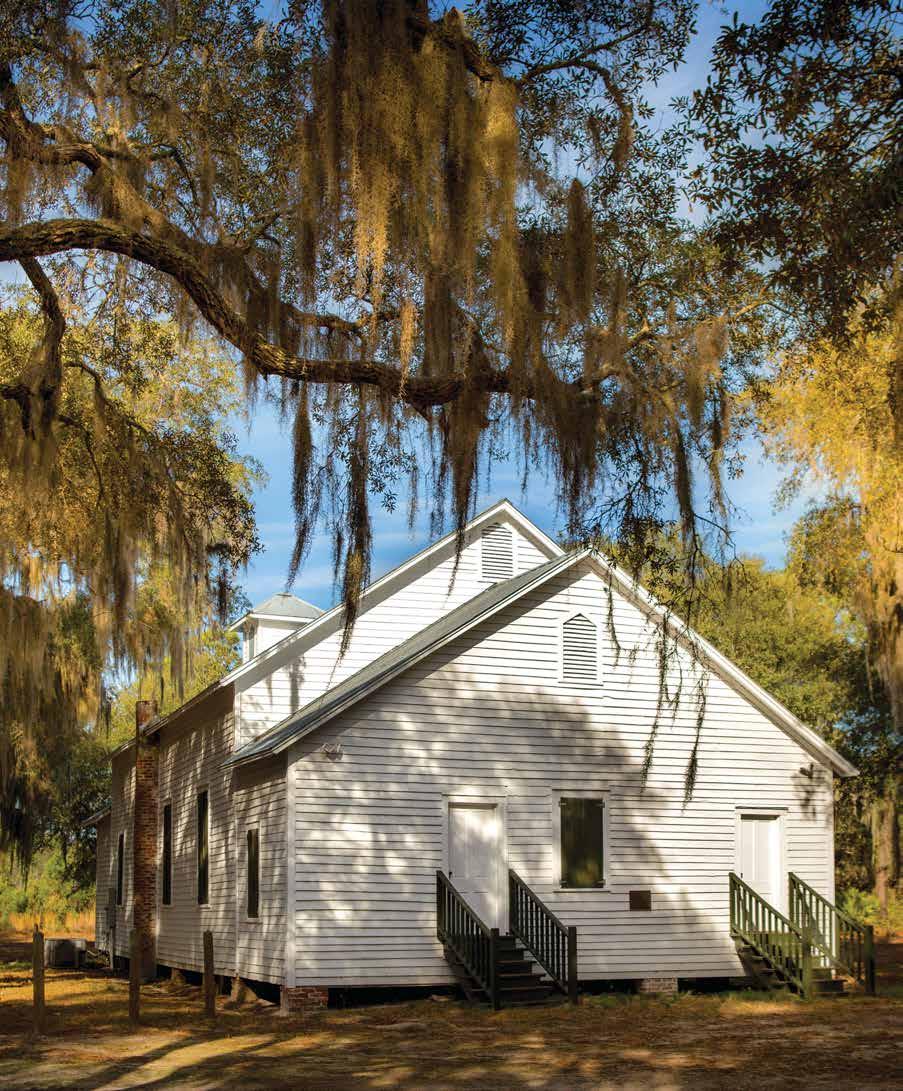

“Slightly off the beaten path is the First African Baptist Church at Raccoon Bluff. Built in 1900, the church has been ‘saved’ on numerous occasions throughout the years, according to several stories I heard while on Sapelo – from a tornado skipping right over it, yet leaving it unscathed, to the timely arrival of lumber washing ashore miraculously, just as renovations were desperately needed. It’s a place that exudes a spiritual peace and celebrates a well-deserved seat on the National Register of Historic Places.”

“I left my wife and kids asleep in Hog Hammock and ventured out well past midnight in a beat-up Ford pickup, flashlight duct-taped to the hood because, of course, the headlights didn’t work. It was midFebruary and freezing, but clear. I spent an hour or so shooting here working on this image. The Sapelo lighthouse, built in 1820, is the nation’s second oldest brick lighthouse.”

new book Sapelo: People and Place on a Georgia Sea Island, scheduled for release from the University of Georgia Press early in March. His lecture will offer fresh insights into the diverse history of Sapelo, particularly regarding the island’s unique African American Geechee culture and legacy. His lecture will include rarely seen historical photographs. Having served as manager of the Sapelo Island Reserve for over 20 years, Buddy’s knowledge of the island is unparalleled. Photographer Ben Galland, whose color images illustrate the book, will also be present and will take part in the book signing that will follow the lecture. The lecture takes place at the A.W. Jones Heritage Center at 6:00 p.m.

When asked about the new Sapelo book, Buddy shares that it’s been by far his most enjoyable project and that it was an incredible learning experience for him. That’s surprising to hear from someone who spent decades working on Sapelo. Sullivan explained, “Sapelo is in my blood, and when I retired after 25 years, I was looking for a research project. This was approaching Sapelo from a different perspective. It is such a unique place because of its relative isolation and relative inaccessibility. The level of cultural preservation is extraordinary.” In learning the history and speaking to people like Cornelia Bailey, looking at the census data, and the agricultural information, Buddy discovered there was no definitive book tying it all together. That became his project for the next three years. He brought his own unique perspective as manager for Sapelo Island Reserve for over 20 years to the task, took advantage of the opportunity to learn new things, and enjoyed it all immensely. “It was something in there that just had to get out,” he quips.

Buddy will serve as the Historical Society’s expert guide on a field trip to Sapelo Island. Due to the limitation requirements of 34 people per tour, two tour dates are available: April 11 and April 18. The tours will explore Long Tabby and the Thomas Spalding sugar mill, Hog Hammock community, the UGA Marine Institute, the 1820 lighthouse, Nannygoat Beach, and the Howard Coffin/R.J. Reynolds, Jr., Mansion. Lunch will be provided at the beach pavilion on April 11. On April 18, lunch will be provided at the Coffin/Reynolds Mansion. The cost is $75 per person, including round trip motor coach transportation from the A.W. Jones Heritage Center, Sapelo ferry ticket, island bus tour, and lunch. Departure time is 7:00 a.m. and return is at 4:00 p.m. Call 912.634.7090 to register.

In addition to Buddy and Ben’s upcoming book on Sapelo, we also highly recommend Buddy’s previous works, including Early Days on the Georgia Tidewater: A New Revised Edition. In addition, the collaborations between Ben Galland and Jingle Davis, Island Time: An Illustrated History of St. Simons Island, Georgia, and Island Passages: An Illustrated History of Jekyll Island, Georgia are excellent and visually gripping accounts of St. Simons Island and Jekyll Island. For personal narratives from individuals who have lived on St. Simons Island, in Brunswick, and on Sapelo, Steven Doster’s book Voices from St. Simons: Personal Narratives of an Island’s Past, is invaluable. Doster has masterfully captured stories from local residents that bring to life the fluid history of the area, the family connections, the preservation of a special heritage, and the awareness of the changing times. It’s easy to imagine yourself on a front porch with a tall glass of sweet tea listening to the tales of these days gone by. To preserve this rare and precious voice within our community we need to find more of these stories and drink them in. Take the tours. Visit with historians, scholars, musicians, teachers, neighbors. Listen to what they share. Write it down. Share it.

The Tale of a

Georgia Power-Full Pair

We took time to visit with Shirley Douglass recently, who shared a story of her own. Shirley and her husband, Judge Orion Douglass are wellknown for their volunteerism and work in the Golden Isles community. Judge Douglass was a founder of The Fourteen Black Men of Glynn whose mission was to mentor young African American boys and help more to graduate from high school each year. He continued working toward this purpose as an organizing chair of Communities in Schools and a co-chair of the

United Way’s Graduation Blueprint Committee. He’s also been active with the Boy Scouts of America, College of Coastal Georgia Foundation, and other organizations. Shirley is equally active, the former Georgia Power employee has been a leader in the March of Dimes, the YWCA/YMCA, American Cancer Society, and The Links. The couple is also passionate about the arts and preservation of history. In fact, one of the things Judge Douglass would love to see is the recognition of the historical significance and important community role of Selden Park –a spot he regularly visited through his youth and adulthood. When recounting the musical performers that visited Selden Park in the days of the “Chitlin Circuit,” Amy Roberts said with a chuckle: “Ask Orion. He’d know that better than I would probably.”

Judge Douglass’ groundbreaking role as the first African American jurist in Brunswick who held his seat without challenge from 1992 until his retirement from the bench in 2012 isn’t a new story. The Douglass’ involvement as volunteers and leaders in the African American community and beyond is welldocumented. We wanted to hear a different story. We looked instead at the longlasting, loving marriage of these two active people who are passionate about their community and their family, and asked Shirley to tell us their love story.

They met in Waycross not long after Shirley had started at Georgia Power. Orion had moved from Atlanta to St. Simons Island and was working in Waycross on a case that required community involvement. She recalls that they were there at a meeting at the church about that project when he handed her his business card and said, “Call me.” She said she thought nothing of it, that he was suggesting if she needed his help with legal matters she (continues)

PHOTOGRAPHY BY KELLI BOYD AND MONICA LAVIN OF LAVIN LABEL

CELEBRATING 30 YEARS OF BUSINESS. WE LOOK FORWARD TO SERVING YOU FOR MANY MORE YEARS!

Shops at Sea Island

600 Sea Island Road St. Simons Island 912-634-8084 Monday-Saturday 10-5:30

AG Jeans, BCBGMAXAZRIA, Dolce Vita, Eric Javitz, Foley & Corinna, Free People, Jack Rogers, Krazy Larry, Lilly Pulitzer, Mara Hoffman, Nic+Zoe, Oliphant, Show Me Your Mumu, Tribal, Trina Turk, Tyler Boe, Vineyard Vines and many more!

www.cloistercollection.com

512 Ocean Boulevard St. Simons Island, GA 31522 912.634.9977 www.mulletbayrestaurant.com Live Music on the Deck ENJOY FRESH FISH & SEAFOOD DAILY ON the OPEN AIR DECK

should get in touch. Since she didn’t, she didn’t call.

“Now,” she says with a dazzling smile, “HIS story is that he came in to Georgia Power because his power was cut off. I don’t know about that. And I told him that I didn’t have his power cut off. But he said ‘You didn’t call me.’ And I said no, that I hadn’t, because I hadn’t needed to. Then he asked if he could take me to dinner. I said yes, and I can tell you that his power hasn’t been off since!” Shirley says they dated for about six months and then she moved to St. Simons Island and they were married about six months later. Nothing fancy. They now have three adult children, Odet, Omar, and Orion Jr. (affectionately known as Punkin). They celebrated their 40th wedding anniversary in October of last year.

What’s the secret to being married that long? Shirley just laughs. She says, “I really don’t know, but I can tell you the advice that I give newly married couples. Don’t start anything that you don’t want to keep up.” She thinks it’s important that neither partner be able to look back and say, “But you let me do this before, so why does it bother you now?” Consistent behavior that allows for growth makes for a healthy marriage.

But how about romance? When asked if they celebrate Valentine’s Day, Shirley responds, “Well, sure. We keep it simple. I usually get him a card and some flowers. He doesn’t bother with that. He’ll ask if I want to go out for dinner and will make reservations someplace nice. That’s our Valentine’s Day.”

One thing that Shirley has learned in her forty years of marriage is that her husband loves to entertain at home. More so than she does, so a night out for dinner is definitely alright with her. If staying in for a quiet night with the family, however, she might pull out an old family favorite recipe, like this bread pudding her grandmother Maggie Jane Wells Hill used to make. She says, “It’s more like a custard, than the bread pudding you’re used to.”

Grandma’s Bread Pudding

6 to 8 slices of bread (light/white bread) 1 stick of butter (softened) 6 eggs ¾ cup of sugar 1 1/3 cup of milk 1 tsp. vanilla ½ tsp. cinnamon

Layer bread in bottom of a 13x9 pan. Beat eggs, sugar, and milk together. Add vanilla and cinnamon. Spread butter on top of bread and pour mix over buttered bread. Bake at 350 degrees for 30 to 35 minutes or until center is set.

A simple, delicious recipe passed down in the family and now shared with us along with a simple story of love, family, and community. Proof that sometimes the simplest things really are the best.

We encourage you to get out and explore the islands this month and learn about the rich heritage of the African American people of the coast. Visit Sapelo. Tour the cemeteries. Listen to the recordings of the singers and the shouters. Read some of these wonderful stories and spread your knowledge like wildfire to help keep it alive. It is this rich heritage that makes this special community what it is today.

The staff at Elegant Island Living would like to thank everyone who contributed to this month’s feature. Our gorgeous cover model Nicole Mahony, an 8th grade physical science teacher at Jane Macon Middle School, graciously posed for hours after the final bell one afternoon. Becky Nelson was the seamstress extrordinaire who made the dress Nicole wore and the backdrop behind her. It’s always a pleasure working with Beth Hall from Elizabeth Lee Makeup for a flawless face. Nick Toth and Theresa Rowan from The Darkroom Photography are responsible for beautifully capturing the vibrant image. Julie Andrew was there to do whatever was needed from choosing fabric to snapping shots on a very chilly day on Jekyll Island. Mason Stewart and Patty Deveau lent their voices with interesting stories about Shouters and the Harrington School. Amy Roberts, Susan Durkes, and Buddy Sullivan also added a wealth of information. Ben Galland’s photos of the Harrington School and Sapelo Island are inspiring, and Paul Meacham can shoot for us anytime! Shirley Douglass is the perfect companion for a chat over coffee. We’re happy that you’re all part of our “village.”

CHANNING OF OUR TWEEN LINE, ”CHANNING,” BY ELIZABETH LEE MAKEUP.

ENHANCE YOUR NATURAL BEAUTY

Kicklighter-Hall Salon and Elizabeth Lee Makeup Serving The Golden Isles and Savannah

We specialize in designing hair and makeup to enhance your bone structure and magnify your natural beauty.

912.266.7006

elizabethleemakeup@gmail.com elizabethleemakeup.com kicklighter-hallsalon.com

Valentine’s Day is a Day for Flowers!

Fresh Arrangements, Chocolates, Balloons, Stuffed Animals, Blooming and Green Plants, Unique Assortment of Gifts and Gourmet Food Baskets.

912.634.9622

1700 Frederica Road, # 103 acourtyardflorist.com