16 minute read

Going gray

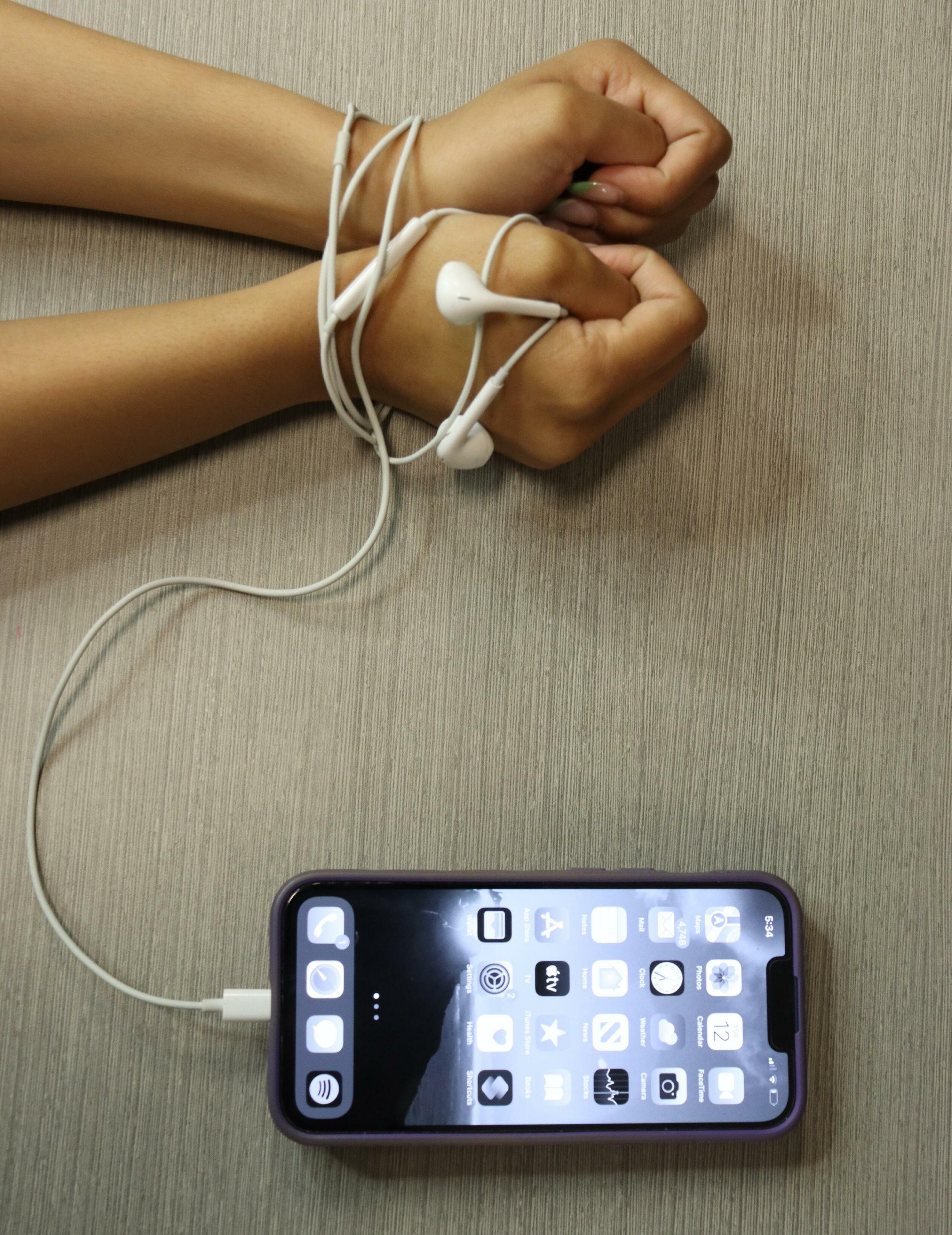

MVHS students share how they’ve unlearned their screen addictions BY JAYANTI JHA

Using grayscale, a phone setting to remove all color from the screen, would invoke panic in most phone users. Every app icon, widget and notification would lose all of its vibrant colors. Websites would become bland and the hundreds of posts on Instagram would no longer be eye catching. But for sophomore Olivia Ho, turning her phone to grayscale is a reminder for her to put down her phone and get back to work.

Advertisement

“I think it definitely helps me reduce my screen time on my phone,” Ho said. “If you open up your phone and it’s grayscale, you’re like, ‘Oh I should not be on my phone right now,’ so then you put it back down.”

Ho saw immediate benefits to changing her phone to grayscale — one of the first steps in unlearning her screen addiction. According to Google design ethicist Tristan Harris, switching to grayscale and reducing the number of colors on the screen lowers the impulse to continue using one’s phone by removing “positive reinforcements.”

“At first, when I deleted Instagram, it was to reduce going on the [app’s] Explore page,” Ho said. “I needed that app because I was still texting people on it, but grayscale helped me still retain that while being able to spend less time on parts of Instagram that I shouldn’t be looking at as much.”

With the addition of grayscale to remind her to focus on life off the screen, she hopes to use her limited screen time on apps she thinks are “better to redirect [her] screen time towards,” like News and Books. Grayscale can be implemented in the settings of most phones — on iPhone, the mode can be enabled through the ‘Display & Text Size’ section in the Settings app, then navigating to ‘Color Filters’ and turning the toggle on the page to on.

For junior Avani Kulshreshtha, less “filler space” in her day to be on her desire to unlearn her screen her phone. On the other hand, she addiction began with a realization says during distance learning, there after examining her screen time — she “was nothing else to do” and not many found that she was spending around people to talk to every day. five hours on Instagram and TikTok Similarly, junior Jerry Hu says that each day, and thought it “didn’t make he doesn’t text very many people — sense [to be] spending half of [her] time over time, he has created a natural on someone habit of controlling his else’s life.” “I think I I DIDN’T WANT screen time, particularly from a young age. He realized that THE FIRST WAKING says he glances up at every single MOMENTS TO BE the time whenever he is morning, the first thing I did was open Instagram or TikTok, ABSORBED LOOKING THROUGH SOME STRANGER’S FEED. on his phone watching YouTube, going on Discord or texting his friends to avoid losing and I realized track of time. After a that wasn’t JUNIOR AVANI set amount of time, he’ll something I wanted to do KULSHRESHTHA resume working. “I guess a good way in my life,” to stop your addiction is Kulshreshtha said. “I didn’t want the just by hiding your phone somewhere,” first waking moments to be absorbed Hu said. “And keeping it away from looking through some stranger’s feed. your desk so that if you want to look I feel like [the morning] should be for your phone, you can’t find it and so devoted to myself.” you just return back to work.” For Kulshreshtha, a main factor in As Kulshreshtha says, she’s still in a this decision was being able to focus on “gradual process,” but she advocates her academics without distractions — for a change in mindset for others she’s implemented apps like “Plantie,” trying to unlearn their screen addiction. which grows a virtual fruit bush for “I think it’s one thing to say, ‘I don’t the duration of a work session and want to be using these apps because stops growing once you exit the app. it’s toxic for me,’” Kulshreshtha said. She also sees “And it’s another thing to be like, ‘I don’t 70% mental benefits of spending less time on her phone, saying that she has more “original thoughts” want to be on these apps, because I don’t want to devote so much of my day to someone else,’ because I think everyone is a little bit narcissistic. And so when you adopt that kind of mindset, it’s a lot more effective.” of MVHS students without “TikTok sounds going feel addicted to their screens through [her] head.” *According to a survey of 152 people However, a worry for her was not being able to “keep up with trends” that originated on TikTok and Instagram — she’s found she now has had more “intellectual conversations” without having these trends being the basis of conversation. Kulshreshtha says because these conversations can happen in-person rather than in remote learning, there’s

UNDER MY SKIN

Unlearning the burden of physical insecurities BY DIYA BAHL

It was 80 degrees one summer day, the sun beating down on me, causing the small of my back to drip with sweat. Yet, I was sitting there in my fleece-lined hoodie and baggy jeans, unwilling to wear anything that would even dare show my skin or reveal any aspect regarding the shape of my body.

My physical insecurities started in middle school, and constantly progressed throughout the years. They began to create a block in my mind, not allowing me to be comfortable in my own skin. I blamed myself simply for what I looked like, which sent me spiraling, questioning my choices, actions, abilities and overall ran my confidence into the ground.

Insecurities carry a weight of burden. Wearing baggy clothes on purpose and never taking pictures of myself were all ways in which my self-consciousness about my body channeled into real life decisions and caused me to pay unnecessary attention to every little flaw in the mirror.

According to a survey of 152 MVHS students, 74% feel insecure about their body image. Constantly comparing myself to what seem like the “perfect” looking people on Instagram and TikTok with their small waists, clear skin and hourglass figures is exhausting. Thinking that nothing looks good on me or worrying that people see me the way I see myself — these all contributed to a never-ending cycle of self-doubt.

But over these past few years, I’ve unlearned the things that caused me to feel this way. Spending so much time with myself over quarantine introduced me to discovering more about me, and I was finally able to learn what I felt good in. I bought a different style of clothes, such as more crop tops and tighter pants, that showed off the very features I used to hide, like my stomach and arms. I started to experiment with makeup, learning how to do eyeliner and buying the right mascara. I took more pictures that I felt good in and surrounded myself with people I could

PHOTO | JIYA SINGH

be my truest self around. I found new recipes that I enjoyed eating, leading me to making the same avocado toast every weekend morning. I explored new music that I liked. Ultimately, I found the things that made me happy.

Finding this new version of myself immediately boosted my selfconfidence and allowed me to look at my physical self in a more positive light. The societal standards for what a girl is “supposed” to look like disappeared from the expectations I set for myself, allowing me to finally accept and feel good about what I saw in the mirror.

It’s important to recognize that another person’s beauty doesn’t take away from your own, and comparing physical features only worsens the insecurity. Learning from an insecurity allows the opportunity for growth, and unlearning the burden of them opens up the ability to become the best version of yourself that you can be.

STUDY SESSION

May is approaching rapidly. For many high school students that doesn’t signal the transition into summer but rather the dreaded AP testing ... BY APRIL WANG AND LILLIAN WANG

IS THAT A NEW LOOK?

What happens when you decide to wear something new and others start to stare? Ignore them, of course! BY SOPHIA MA AND SONIA VERMA

CRY ME A RIVER

How my relationship with crying has changed over the years BY SHIVANI VERMA

My mom was screaming. It was a bit awkward.

My cousin and I were at my uncle’s house to celebrate her 13th birthday with our family. Although the night had started out fun, the festivities eventually dissolved into petty arguments, which then progressed into a full-blown shouting match.

The adults shooed my cousin and I upstairs and away from the quarrel. But it didn’t matter — we had already heard the yelling. My cousin was sobbing, tears streaking down her face as she clutched a pillow, and I … was coloring in a coloring book.

I was only eight years old; I didn’t comfort her. I didn’t do anything at all, because hearing the angry words echo from downstairs didn’t upset me the way it upset her. It wasn’t that I was holding tears back. I simply felt blank.

That was part of a period of time in my life when I didn’t cry at all — not when I was stung by a bee, not when my dad grounded me and not even when my mom and uncle ended up screaming at each other in a Starbucks.

In elementary school, I was often told I was sensible and acted older than my age, and over time, that praise hardened into an unwillingness to be seen as anything else. When others sniffled after a teacher had scolded them or burst into tears because they didn’t get what they wanted, I prided myself on being above them. Unlike them, I had a handle on my emotions. Ever heard of the phrase “Crying is for babies”? I took it to heart. No matter what I was, I would not be a crybaby. I made sure of that.

And yet, as I settled into middle school and puberty trickled in, my hormones staged a coup over my rational thoughts. Suddenly, my relationship with crying changed. Suddenly, my emotions were stronger and sharper, so when my dad snapped at me or when I got a bad grade, tears would begin to prick at my eyes. Suddenly, the mantra I had been living by that demanded don’t cry, don’t cry, don’t cry seemed less and less effective.

It began to seem like everything was just harder in high school: my arguments with my dad hurt more, I was in my first relationship, I was at a new school where I knew nobody — there was too much change to count. My emotions were also more heightened and painful, and I didn’t know who to tell, or even what to say. There were days when I wished I could start sobbing in class just so people would ask me what was wrong. But the tears just wouldn’t fall.

Talking about crying was equally difficult — asking someone when the last time they cried felt just as awkward as asking if they had lost their virginity. Without a way to talk about or express my emotions, I felt stuck. It must have been building and building for a long time, because junior year, I finally snapped.

Besides when I was an infant, I have never cried more in my life than I have in the last two years.

Forced to stay at home during the pandemic, there was nowhere to run from my feelings. So when I got overwhelmed by school work and friendship problems and was left feeling completely alone, I would crawl under blankets with that growing bubble of emotion in my chest and finally just … cry. BLOOM SHIVANI VERMA

It was as if I’d been holding back a river with a hastily-made dam. Hidden away from my family, it felt liberating to let the sobs wrack my body, no matter the reason. There, I wouldn’t be judged or seem like I was overreacting. And once I started, I couldn’t stop. Tears would collect along my eyelashes and spill at anything and everything, no matter how petty or meaningless. During the pandemic, I cried at least once or twice a week. The “Google — Year in Search 2018” YouTube video made me sniffle without fail, every time I viewed it. Once, my heart clenched and I teared up when the narrator in a documentary about the evolution of country music said a sentence in a specific inflection. A documentary about country music. I no longer see being emotional as a bad thing. I actually admire people IT WAS AS IF I’D BEEN HOLDING BACK A RIVER WITH A who are able to express themselves freely. To be honest, I’m still getting there; I can’t cry in public, even if I feel like I want to, and none of my closest HASTILY-MADE DAM. friends have ever seen me shed a tear. And I’ve noticed that allowing myself to fully feel my emotions and let them run their course helped me be less hard on myself. Not only that, I’ve become more capable of empathy and more willing to help people who may be feeling down. Feelings don’t scare me anymore. As a senior, I’ve become exactly what I used to scorn. So I’ve decided to let go of “crying is for babies” and adopt a new mantra — I’m going to cry myself a river, build a bridge and take all the time I need to get over it.

WHERE ARE WE NOW?

BY ISHAANI DAYAL, ANUSHKA DE, TARYN LAM, SARAH LIU, JANNAH SHERIFF AND MIRA WAGNER Identifying and exploring the changes that have occurred at MVHS since the Black Lives Matter Movement, the LGBTQ+ Movement, the Mental Health Movement and the #MeToo Movement gained popularity and national appeal.

BLACK LIVES MATTER

BY SARAH LIU AND MIRA WAGNER

Exploring how the BLM movement has changed things at MVHS in recent years

On Thursday, March 10, junior Greyson Mobley found that the bathroom in the lower B building at MVHS had been graffitied with the phrase “Kill all n******.” He perceived the act as “stupid and childish,” but the incident left him wondering about the progress towards racial equality at MVHS in the past few years. Mobley was also especially bothered by his perception of the lack of consequences in response to this occurrence.

Principal Ben Clausnitzer states that the type of punishment varies on a case-tocase basis. However, if the perpetrator is identified, the consequences w o u l d likely entail suspension and potentially expulsion because “in a situation like this, [he] can’t see any way where someone would remain on campus.”

Superintendent Polly Bove highlights how administration has worked on transparency by sending out messages about incidents like this to all students and families, whereas students may not have been recipients in the past.

“That’s something we’ve learned over time,” Bove said. “I don’t want to tell you we started out being incredibly insightful about knowing that that was a big step to take, but it really was a learning that we took seriously. We still have our own processes, but we want to work that through and we want to do our best to find who’s doing these things, and then address it.”

Still, Mobley feels there is a lack of investigative work he believes the administration should be doing. “They should definitely make it more of a big deal instead of sending out one email,” Mobley said. “We haven’t really done anything to stop it, [so] I think [we should] take more action and try to figure out who it was and solve their behavior.”

Clausnitzer states that as no one has reported any new information regarding the graffiti incident, the administration has been unable to progress its investigation. However, he understands that some individuals may want to learn more about the incident and invites them to contact

him to share their thoughts. “It’s always helpful if someone is feeling that they’d like more information that they reach out to us,” Clausnitzer said. “It’s important for me to hear how they’re feeling and what they’re thinking. It’s important to me, it helps me learn and grow as a leader as well.” Associate Superintendent Tom Avvakumovits says the administration 66% of MVHS students is constantly finding ways to improve its “focus on inclusion and equity.” He adds that recently, the district has taken some notable steps toward fostering a more inclusive environment for all their students. “I used to be a teacher at Cupertino High School, and in our sophomore year, and this was a zillion years ago, all of our authors except one were say the BLM movement has people who looked like me and Mr. changed things slightly or greatly since its emergence at MVHS Clausnitzer,” Avvakumovitz said. “So there’s been a huge movement, [and] we need to look at literature in ways *According to a survey of 103 people where we diversify the perspectives, and so now in all of our English classes throughout all five of our comprehensive high schools there’s much more inclusion of perspectives of color.” Clausnitzer articulates that the administration has since also implemented Equity Task Forces, groups of students and staff that work to address racial inequality in all five high schools in the district. “That commitment that we are

thinking about is transformational, and we’re talking about equity [and] social-emotional learning,” Clausnitzer said. “We still have to have a focus and need to have a focus around racial equity. We can’t lose that. As the Equity Task Force, the importance is focusing on racial equity during that work [and] what became our focus and continues to be.”

While the Equity Task Force seeks to educate students on how to become more inclusive and creates plans for the future of inclusivity on campus, Mobley believes that the root cause of these racist incidents stems from a deeper issue. Although he feels that racism is prevalent in the culture at MVHS, he thinks it is well concealed due to California being a largely Democratic state. He notices that as a result, it is harder to solve these issues of racism. “I think the racism around here, especially, is a lot less noticeable because people know it’s not OK, so they hide it,” Mobley said. “But it’s very obvious that it’s still a problem because of, obviously, what happened.”

Avvakumovitz understands the struggles Mobley identifies, and highlights how the administration is WE STILL HAVE focused on continuously growing and improving to make schools in the TO HAVE A FOCUS AND district more inclusive. “This is my 29th year in the district, and ever since I started, we’ve had a NEED TO HAVE A strong focus on inclusion and equity,” FOCUS AROUND RACIAL EQUITY. Avvakumovitz said. “But for me, I think what BLM did is an example of ‘Hey, some of the initiatives that we’re currently working on maybe PRINCIPAL need to be more explicit and direct about the work we are striving to BEN CLAUSNITZER do and continue to work to do.’ [It] really does address or attempts to address the concerns of some of the less-represented cuts of students, including African Americans.”

PHOTO | AYAH ALI-AHMAD

PHOTO | AYAH ALI-AHMAD

Protesters hold up cardboard signs during a Black Lives Matter rally in a neighborhood.