3 minute read

Christian Cooper talks the magic of birding at 92 Street Y

By KAREN JUANITA CARRILLO Amsterdam News Staff

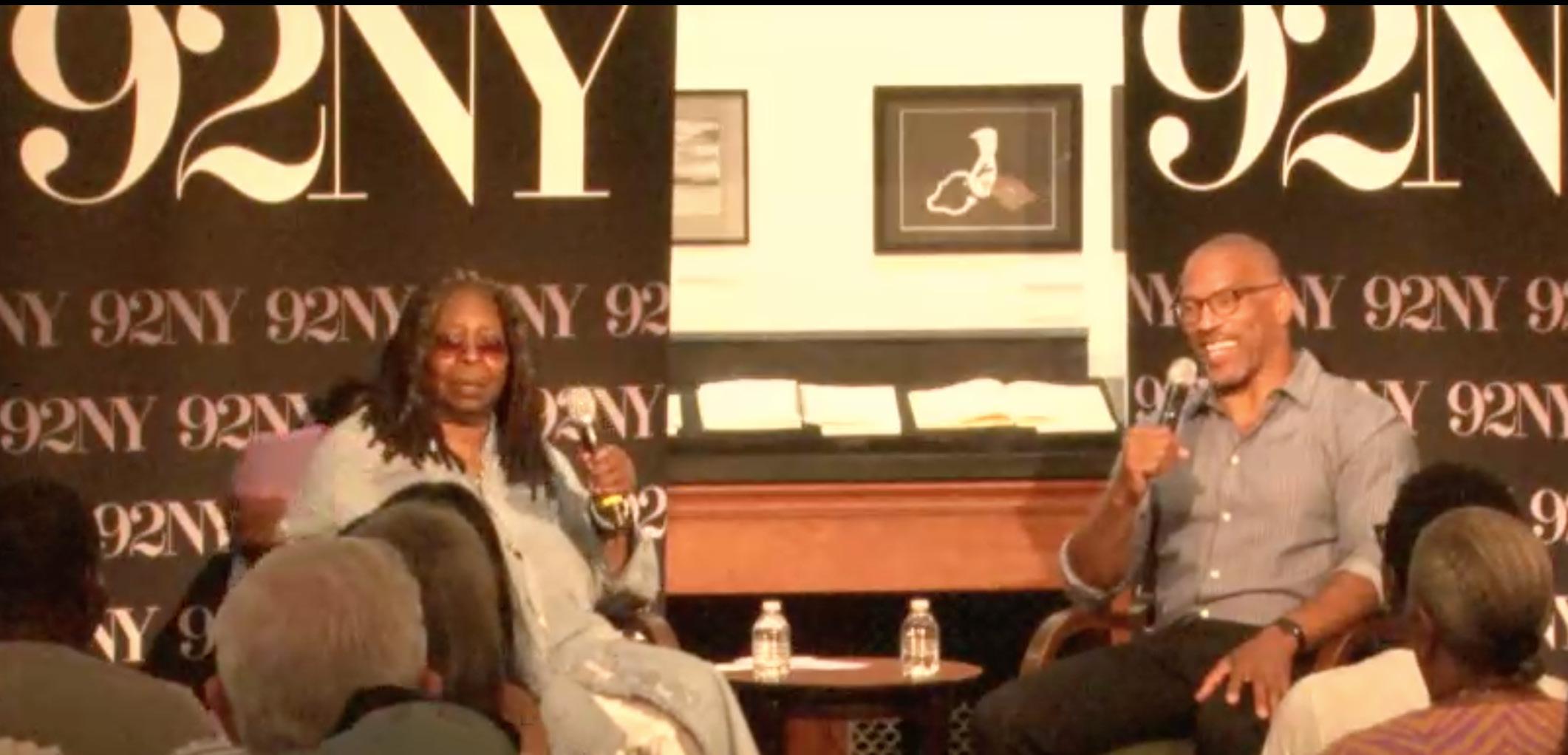

New York-based science writer and famed bird enthusiast Christian Cooper was at the 92nd Street Y on July 12 to talk about his hosting of Nat Geo WILD’s new show, “Extraordinary Birder,” and writing his memoir, “Better Living Through Birding: Notes from a Black Man in the Natural World.”

During a talk hosted by actress Whoopi Goldberg, Cooper spoke about how birdwatching became a central part of his life at a young age and how he got caught up in the world of birding.

When Goldberg asked Cooper to explain the difference between a “spark” bird and a “life” bird, Cooper said in birding lingo, a spark bird “is the bird that got you started—the bird that made you say, ‘Wait. What is this? What is this bird? And why am I noticing birds now and why can’t I stop?’”

His own spark bird was a red-winged blackbird. “When I was a kid, at about 9 or 10 years old, I put a bird feeder up in the backyard and kept wondering what all these crows with red in their wings were. I thought for a couple of seconds that I had discovered a whole new species of crow,” he said. But his research led him to understand that he was actually seeing a red-winged blackbird.

A life bird is a bird that you’ve never seen before, Cooper said. These are the birds that dazzle bird enthusiasts and draw them in, because it makes them realize there will always be a new bird to watch out for. No birder has seen every bird in existence, so there’s always a new life bird to pursue. “Some of them become like holy grail birds: You really want to see it one day,” he mused. “And then, one day, here it is and it kind of blows your mind. And that’s one of the best feelings in birding.”

On his “Extraordinary Birder” program, Cooper was able to see one of the life birds he’d been searching for: the small, brightly colored, Puerto Rican tody. When the series went birdwatching in Puerto Rico, Cooper got to see the tody and was blown away. “It is adorable: it’s kind of green above, white-ish below, some red on it,” he reminisced. “And this oversized head with the oversized orange beak––it’s just the cutest thing alive. The great thing is this bird wanted to try and lead us away from its nest, so it was putting itself in our face so that we would follow it instead of going toward its nest.”

Being able to travel across the nation with his new show has exposed Cooper to a larger variety of birds than had become routine when he mostly did birding activities along the U.S. East Coast. Some of the other locations his show takes viewers to are Alabama,

Hawaii, Palm Springs, and Washington, D.C.

The sounds that birds make add to the attraction. “First of all, birds definitely have different dialects,” Cooper said. “I was down birding in Maryland a couple of years ago when I heard this bird sing and I was like, ‘What the heck is that?’ It was a cardinal. I know the cardinal sounds cold, but this cardinal was a southern cardinal. It literally had a southern dialect.”

Birds across the U.S. are as distinct as the people and the environments they live in. Birding and learning about birds is fascinating, and it’s a peaceful pastime that many Black bird enthusiasts and ornithological professionals participate in. Cooper lauded some of the less popularly known but important Black birders who are contributing to the field: Clemson University’s wildlife ecologist, J. Drew Lanham, who last year won a MacArthur Genius award on the basis of his writings about Black birders and Black nature enthusiasts; Scott V. Edwards, a Harvard University professor of organismal and evolutionary biology; and the self-styled “Hood Naturalist” Corina Newsome, who is one of the co-organizers of Black Birders Week.

“I may be, at the moment, the most visible,” Cooper said about being a recognized Black birder. “But you know, there are tons of us. There should be more. And that’s one of the things I hope that I am carrying forward. I’m hoping that with a Black man––a Black person––being the face of this major birding show, that a lot of Black and brown kids might look at it and say, ‘Maybe I can do that too.’”