6 minute read

In the Classroom Out & About ..........................Pages 8,9

Cudjoe Lewis’ saga as told by Zora Neale Hurston in ‘Barracoon’

By HERB BOYD

Special to the AmNews

During a recent panel discussion at the Brooklyn Book Festival, the presence of Lucy Anne Hurston was instructive as she delved into the history and legacy of her aunt Zora Neale Hurston, most notably her publication of “Barracoon.” It was not until recently that Hurston’s story about the last slave ship to arrive in the United States and her engrossing interview with Cudjoe or Cudjo Lewis was finally published by Amistad. Even so, there are still thousands of Americans who have yet to discover Lewis and his phenomenal tale.

Lewis’ saga is one that Hurston delivered intact, recording Lewis’ words as he spoke them, dialect and all—that may have been one of the problems halting publication, though a deeper concern was who the writer was and the subject. Black writers, particularly one so emboldened with integrity as Hurston, have often met with reluctance when presenting their creations, and Hurston did a remarkable job of capturing Lewis’ trials and tribulations, in his own voice.

Born as Kossula or Kossola c. 1841 in a region of Africa now called Benin, he was a member of the Yoruba people. “My father he identify O-lo-loo-ay,” he told Hurston in 1935 in one of several interviews she conducted with him. “He not a wealthy man. He have three wives. My mama she identify Ny-fond-lo-loo. She de second spouse. My mama have one son befo’ me so I her second little one. She have 4 mo’ chillun after me, however dat ain’ all de chillun my father received. He received 9 by de first spouse and three by de third spouse.” And this is the way Hurston retained his language and the challenges she faced in the transcription.

But let’s allow Zora to recount their engagement. “I had met Cudjo Lewis for the first time in July 1927. I was sent by Dr. Franz Boas to get a firsthand report of the raid that had brought him to America and bondage, for Dr. Carter G. Woodson of the Journal of Negro History. I had talked with him in December of that same year and again in 1928. Thus, from Cudjo and from the records of the Mobile Historical Society, I had the story of the last load of slaves brought into the United States.

“The four men responsible for this last deal in human flesh, before the surrender of Lee at Appomattox should end the 364 years of Western slave trading, were the three Meaher brothers and one Captain [William “Bill”] Foster. Jim, Tim, and Burns

Meaher were natives of Maine. They had a mill and shipyard on the Alabama River at the mouth of Chickasabogue Creek (now called Three-Mile Creek) where they built swift vessels for blockade running, filibustering expeditions, and river trade. Captain Foster was associated with the Meahers in business. He was ‘born in Nova Scotia of English parents.’”

Zora listed several reasons given for this trip to the African coast in 1859, “with the muttering thunder of secession heard from one end of the United States to the other. Some say that it was done as a prank to win a bet. That is doubtful. Perhaps they believed with many others that the abolitionists would never achieve their ends. Perhaps they merely thought of the probable profits of the voyage and so undertook it. The Clotilda was the fastest boat in their possession, and she was the one selected to make the trip. Captain Foster seems to have been the actual owner of the vessel. Perhaps that is the reason he sailed in command. The clearance papers state that she was sailing for the west coast for a cargo of red palm oil.

“Foster,” Zora continued, “had a crew of Yankee sailors and sailed directly for Whydah [Ouidah], the slave port of Dahomey. The Clotilda slipped away from Mobile as secretly as possible so as not to arouse the curiosity of the Gov-

ernment. It had a good voyage to within a short distance of the Cape Verde Islands. Then a hurricane struck and Captain Foster had to put in there for repairs. While he was on dry-dock, his crew mutinied. They demanded more pay under the threat of informing a British man-of-war that was at hand.”

According to Hurston and other authorities on the slave trade, Lewis or Kossula was taken prisoner by Dahomey Amazons in 1860 and taken to the port of Ouidah where he was sold to Captain William Foster of the “Clotilda” ship. The ship belonged to Timothy Meaher of Mobile, Alabama. What Meaher and his associates had done was a violation of the law that prohibited the transporting of slaves. Facing charges for the violation, Meaher and his partners, between the time when summons were issued for their arrest and when they received them, dispersed their captives, hid them, thereby avoiding prosecution, since the evidence was hidden.

With the advent of the Civil War, Lewis and the other captives lived as de facto slaves with various relatives of Meaher. It was during this time that Lewis acquired his new name. The Emancipation Proclamation also brought a new condition and they set out to find a community at Magazine Point, just north of Mobile. Soon they were joined by other formerly enslaved Africans and named the region Africatown, now a historic district. In the 1930s, Hurston began her folkloristic trips to the South and Lewis became her most resourceful informant on the creation of the town and the adventure aboard the last slave ship.

In the 1860s, Lewis began a common-law relationship with another survivor of Clotilda, called Celia and they formally married and had six children. Lewis outlived his wife and all of his children. He worked as farmer and laborer until 1902 in Mobile where he was injured in a train collision. Unable to resume his work, he became a sexton at the local church where he was supported by the community.

It was not until Oct. 24, 1868, that Cudjo and the other African-born captives became naturalized citizens. By then he had acquired enough information about the American way to sue the railroad company after his accident who refused to pay damages. He retained an attorney and won a settlement of $650 but the award was overturned on an appeal.

Two years after Hurston published her most famous book “Their Eyes Were Watching God,” Cudjo died, reportedly at the age of 95 or 96. His reputation as being the last survivor of the slave trade was contested, and that’s a subject we will return to later in more expansive way.

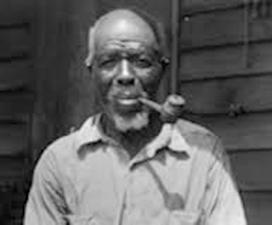

Cudjo Lewis

ACTIVITIES

FIND OUT MORE

The work and research of Hurston’s niece and historian Sylviane Diouf are reliable and valuable resources on this subject.

DISCUSSION

With the publication of “Barracoon,” there has been renewed conversation among scholars about Hurston’s extensive literary and anthropological contributions.

PLACE IN CONTEXT

Cudjo was born in Africa and lived a good portion of his life in Alabama.

THIS WEEK IN BLACK HISTORY

Oct. 10, 1917: Pianist/ composer Thelonious Monk was born in Rocky Mount, N.C.

Oct. 14, 1964: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is the youngest recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize.

Oct. 16, 1859: John Brown leads an insurrection at Harpers Ferry.