HARD LABOR

“AT THE BANQUET TABLE OF NATURE, THERE ARE NO RESERVED SEATS. YOU GET WHAT YOU CAN TAKE, AND YOU KEEP WHAT YOU CAN HOLD. IF YOU CAN’T TAKE ANYTHING, YOU WON’T GET ANYTHING, AND IF YOU CAN’T HOLD ANYTHING, YOU WON’T KEEP ANYTHING. AND YOU CAN’T TAKE ANYTHING WITHOUT ORGANIZATION.” - A. PHILIP RANDOLPH

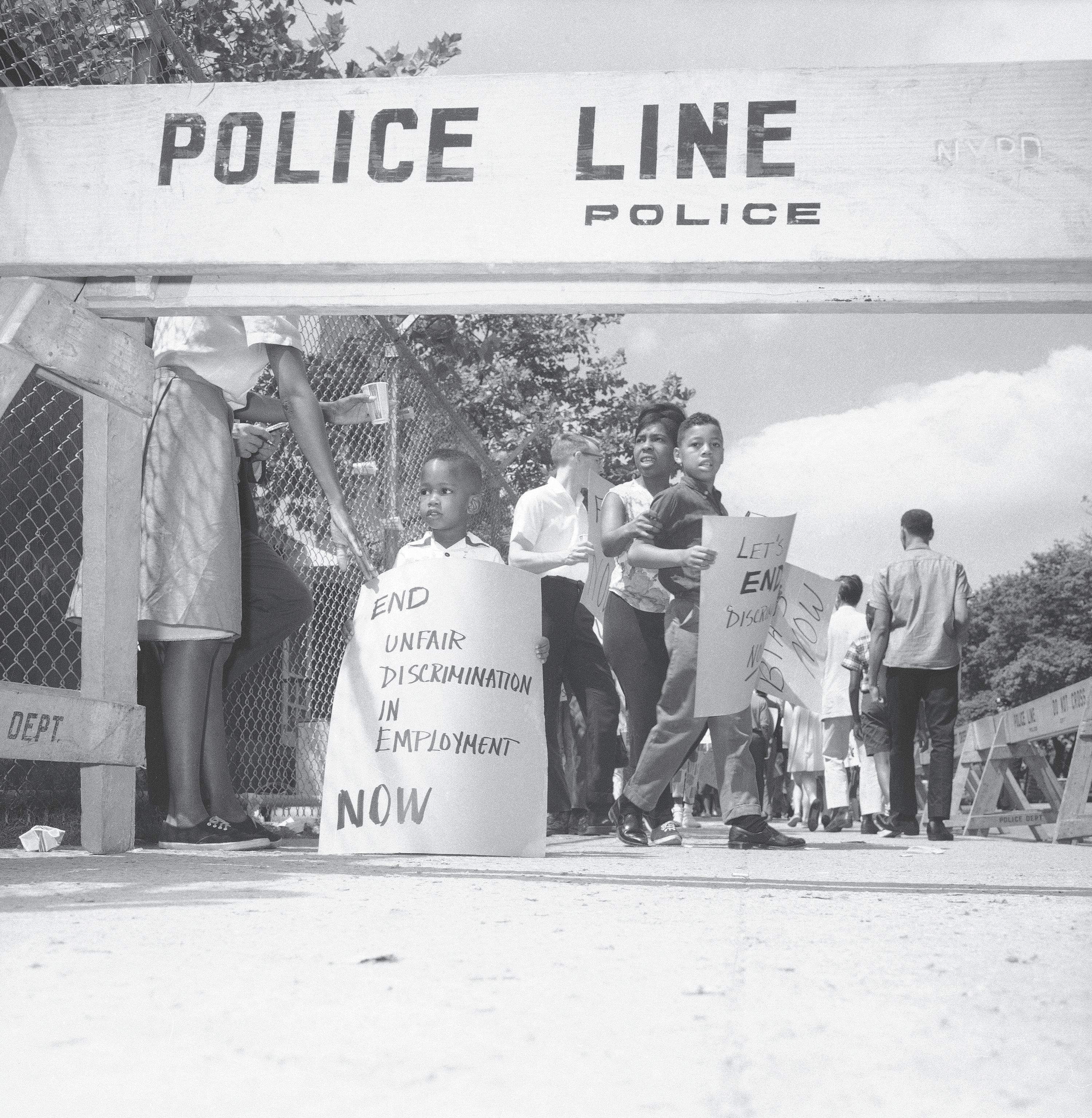

an Amsterdam News article told readers in the summer of 1963, when community and labor activists, as well as clergy, had had enough of discriminatory labor practices on local construction sites.

In Brooklyn, the structures that would become SUNY Downstate were rising from the ground, but Black and Latino construction workers were nowhere to be found. Demonstrations co-sponored by the Negro American Labor Council, Urban League, NACCP, Congress of Racial Equality, and Southern Christian Leadership Council began picketing and eventually blocking access to the worksite, leading to the arrest of more than 40 activists, in-

form 35 [percent] of [the] New York City population.”

The protests continued throughout June and July with increasing numbers of protesters and hundreds of arrests, and even attracted a young leader named Malcolm X. They were demanding something simple: that the workforce building the hospital look like the community in which it was being built. Eventually the protest leaders came to an agreement with then-Governor Nelson Rockerfeller and construction resumed. But the protest at SUNY Downstate wasn’t the first of its kind nor would it be the last.

But why was it needed at all? Why, in one

lowed and of the hard work by Americans of color and their allies to force our nation to live up to its own ideals.

This series will explore the roots of discrimination that led to the summer of ’63 protests in Brooklyn and many others like it around the nation, and how activists, community, and union members worked over decades to force change. It will also explore how high schools and apprenticeship programs are, in the 21st century, helping to ensure that everyone who wants one has an opportunity to access jobs that are often called the “ladder to the middle class.”

Before emancipation, enslaved Blacks were often trained in skilled construction, especially

tinued to be pretty important in the skilled construction industry in the South until the certed effort by white workers to drive Black workers out of the skilled trades and unions often included racial bars on membership. And that persisted into the 1960s,” Jones said

The end of Reconstruction coincided with the ”Long Depression” of the 1870s, as well as the rise of organized labor, both of which helped to put pressure on African American skilled laborers. While some of the new labor unions became more inclusive, according to Jones, the backlash was not long in coming.

By the late 1880s and 1890s, “a lot of unions, particularly the very skilled trade unions, turned inward and make the decision that the the best way to maintain themselves [was] to focus narrowly on the interests of white male workers,” said Jones. “This is the period in which a lot of unions adopt[ed] in their constitution, race and Continued on page S3

gender exclusionary language, [and] they restricted their membership to white men.

“If you can prevent people from getting access to these skills, you can…corner the market on the number of people who are car penters, or who are skilled masons. [Then] you can drive up wages and improve work ing conditions for those few workers by ex cluding the majority,” he added.

The cruelty of Jim Crow and lack of eco nomic opportunity for Black Americans in the former slave states helped prompt the Great Migration, which brought millions of African Americans northward. Skilled workers, or those seeking to join those pro fessions, often found the same kinds of roadblocks in places like New York and Chi cago, and during the early decades of the 20th century, the organized push for rep resentation and access to the skilled trades began in earnest.

The Great Depression and World War II provided fertile ground for the passage of federal labor legislation and Black labor lead ers like A. Philip Randolph began to push for the implementation of these laws without regard to race.

In the summer of 1941, Randolph, along with leaders from the NAACP, Urban League, and many others, threatened a “March on Washington” to protest the discrimination that federal contractors had been allowed to get away with in seeming impunity. In response to these demands, which threatened military production as the nation was preparing to potentially enter World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order that prohibited discrimination in the defense industry.

The wartime order was weakly enforced and expired soon after the end of the conflict, but it began a drive that, in some ways, laid the groundwork of the Civil Rights Movement that followed, with leaders demanding that a permanent non-discrimination law be passed.

“There was this constant push to pass an equal employment law, and that was finally realized with the inclusion of Title Seven, in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. That actually applied not just to federal contractors, but to any employer and any union, it made it illegal for them to discriminate on the basis of race,” said Jones.

There is a false belief among some Americans that we live in a “post-racial” era that began soon after the passage of the Civil Rights Act and culminated with the inauguration of President Barack Obama. But for those struggling to gain access to the skilled trades and construction jobs, nothing could be further from the truth.

In 2022, just 6.7% of American construction workers were African American, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, while making up 13.6% of the population. In New York City, the numbers tell a similar story, with Black residents making up just 13.6% of

construction workers while being over 23% of the population, according to the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

In the immediate aftermath of the passage of the Civil Rights Act, little changed on the ground. Yes, explicit racial roadblocks to entry to unions and employment on worksites was eliminated, but the social nature of employment in the skilled trades meant that barriers still existed.

Post-World War II investment in America’s cities also meant the growing require ment of union labor, according to Dr. Trevor Griffey, a lecturer at the University of California, Irvine. But these construction

and skilled trades unions were still largely excluding members of color.

This made the skilled trades “a flashpoint for protests in the sixties. And it had been long, long simmering because especially as African Americans gained increased access to the military, they gained the trades that they would not be able to get through racially restrictive apprenticeship programs. Then they would go apply to be dispatched and they couldn’t get jobs either through the

delphia Plan,” which began to force companies seeking federal contracts to take what was called “affirmative action” to ensure that these companies employed at least some Black Americans.

But laws and executive orders only went so far. When it came to ensuring that these new regulations were implemented, activists and community members, and even the media, were critical.

“What was really important was the ability to keep the mobilization going, so in places like New York, or Chicago or Detroit, [and] in some cases, in southern cities like Atlanta or Birmingham, where Black workers were sort of well-organized and ready to mobilize, they could force the issue and draw attention to it,” Jones said. “The Black press played a really important role in writing about and publicizing these issues,” he added.

It was this history of decades of mobilizations that set the stage for protests at SUNY Downstate in 1963 in Brooklyn and others that would continue through to the present day. Activists then and now deeply understand that enforcement is everything and ironically, it is those who do not make up the majority who bear the burden of ensuring America lives up to not only its lofty ideals but also its actual laws.

“The beneficiaries of a system cannot be expected to destroy it,” Randolph said decades ago. His wisdom would guide activists in the second half of the 20th century and beyond as they continued the fight to make sure that those working at construction sites looked more like the communities where those structures were being built.

The next part of this series will explore how activists began to force equal access to skilled and construction jobs.

This series was made possible by a grant from the Solutions Journalism Network. Brian Palmer contributed research and reporting to

In the oppressive summer heat of August 1963, the New York Amsterdam News ran a short story on page 7 of its August 10th edition: “Plumber To Be First In Union.”

Just a few hundred words long, the story highlighted “Edward Curry, the 25-year-old Negro plumber on the verge of entering the all-white Plumbers Union, Local 1 admittedly knows little of the reasons for the long well-publicized demonstrations at the Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn.”

For weeks, hundreds of clergy and activists had been arrested while blockading the site that our newspaper in other stories called “near lily white,” demanding that at least 25% of workers be “Negro or Puerto Rican.”

“It doesn’t mean too much to me,” Curry is quoted as saying of the demonstrations, but the timing of the announcement of his barrier breaking hiring was likely a direct result of the demonstrations that had, and would continue on and off for years, to

utive orders and laws were put into place, through the hard work of activists and or ganizers for civil rights, to ensure that the American workplace, including construc tion sites and union halls, became inte grated. But the laws and regulations were meaningless without enforcement and it

century, many of the unions that represented the skilled and highest paid trades like plumbers, electricians, pipe fitters and steel workers still marginalized Black

“A number of those unions were very militant, but also very racially exclusive. And then they fought against the inclusion of racial discrimination prohibitions in labor law,” Dr. Griffey added. With the passage of the Civil Rights Act, racial discrimination in hiring and employment was banned but construction sites continued to be bastions of de facto segregation.

“When an employer needs people, they often tell the people who are working there, ‘we need to hire some more people, go tell your friends, and tell your family’. And so if you have an all white workforce, that’s going to mean that the people who hear about those job openings are all going to be white,” said historian Dr. William Jones of the University of Minnesota, explaining why it was so difficult to diversify worksites despite the passage of Federal nondiscrimination laws.

While he believes that the building trades have made enormous improvements, Jeff Grabelsky, the Co-Director of the National Labor Leadership Institute at AmNews in an interview that “there was a time in New York City when some major unions, in a city that

was becoming majority minority... where there were local unions without a single

During this era, construction unions largely mirrored private industry which also excluded workers of color from the -

ing these construction sites in the sixties. It started in Philadelphia, quickly moved to New York, and then was nationwide. People occupied the arch in St. Louis as it was being constructed,” Dr. Griffey noted.

The threat of action during World War II led to the creation of an executive order which prohibited discrimination in the defense industry. Direct action also led to both the inclusion of Title Seven, in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and President Nixon implementing the “Philadelphia Plan” which began to force companies seeking federal contracts to ensure that they employed Black Americans.

But these hard fights for laws and regulations had their limits Mr. Grabelsky noted.

“Through legal action and community organizing, building trades unions were forced to bring in Black community members. And in some cases, six months later, they were all gone because nothing else changed in the union and they entered this hostile environment that made it exceedingly difficult for them to succeed.”

There was an intense backlash to what would become known as “affirmative action” that pushed back on what little progress was being made at the time.

“There are counter protests against affirmative action in ‘69, that look a little like hate marches,” said Dr. Griffey. In 1970, “a group of construction workers in New York, descend on a peace rally and beat the shit out of the protestors, then march

Continued on page S5

to City Hall and protest affirmative action in the construction trades, [on the] same day,” he added.

Some organized labor officials also found ways to oppose the integration of their unions; and in one case, was rewarded with a cabinet position.

“These are long time Democrats. Many had never voted for a Republican in their lives. They’re campaigning for Republicans on a law and order platform. And when they help with the landslide election of Nixon, [Peter Brennan], the head of New York City building trades is rewarded by being made head of the Department of Labor where he guts what remains of affirmative action in the construction industry,” said Dr. Griffey.

But right wing construction workers and their leaders weren’t the only ones taking to the streets in the 1960’s and ‘70’s. As large, publicly funded construction projects went up in New York and other cities, activists and organizers of color began to demand their fair share.

“There’s these big public construction sites in Black communities, where Black workers aren’t being employed. And so these protests are around the construc -

tion sites to get people employed in those jobs and to open up those jobs,” said Dr. Jones.

“The argument was, ‘Our tax dollars are paying for this construction. We should be able to get these jobs as well.’ And in that case, it was largely the construction, the skilled trades unions that shut Black workers out of these jobs,” he added.

Across the country in Los Angeles, Black workers have also been fighting for their share of the pie.

Janel Bailey, Co-executive Director of Organizing & Programs at the Los Angeles Black Worker Center, spoke to the AmNews about efforts her organization has undertaken to ensure that Black workers are represented on job sites. As L.A.’s mass transit system expanded into Crenshaw, the organization in partnership with other labor organizations negotiated an employment agreement with the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority which they say increased the number of Black workers on the project from zero to 20% in 2015.

“Folks at our organization came together, with allies of course, to really step to Metro and asked them, ‘how you have all this money coming through our neighborhood, but [its] not going to the workers and the families that are actually here?

You need to hire more Black workers’.” Bailey said in an interview.

During their negotiations she said they encountered “the usual things of like, ‘Oh, well, we can’t just say Black [workers] and we don’t know any Black workers’. Which to be perfectly honest, I believe them when they say, ‘I don’t know any Black workers.’ I believe them because the culture of exclusion that they’ve built set up their network such that it doesn’t include Black people.”

Bailey is also critical of labor unions and the apprenticeship system in Los Angeles.

“This culture of exclusion didn’t come up overnight and so I’m naming all these policies that broadly create a culture of exclusion,” she said. Apprenticeship programs are “wonderful for workers because it created a control of the market on labor, such that if you wanted to hire, to bring folks in to do that work, then you had to go through the union and you could set standards. Safety standards and wage standards for workers. Which is beautiful.”

But she went on to say that “the values of the folks who created and maintained that program were anti-Black. And so when they chose to create this wonderful pathway for workers, it was not inclusive of Black workers. And so what we’re seeing

today is the fruits of that legacy.

“That honestly, I think if you take it straight up on paper, the apprenticeship program actually is not problematic. I think it’s actually quite brilliant.... However, applied with the values of the people who had the power to build that, it was anti-Black and it was built in a way that for some was deliberately exclusive. And so we arrive at this moment now where we have this incredible program that only benefits some workers and we’re trying to figure out how to open it up, how to expand it so that it includes workers of color.”

Grabelsky of the National Labor Leadersup Institute at Cornell said, "There is a history of exclusion." He added, “I don’t think race and racism explains everything in our society, but I personally think nothing of any significance can be fully explained without looking at it through that lens.”

Our third installment will examine how organizers in Harlem helped launch a movement to hold builders and unions accountable

This series was made possible by a grant from the Solutions Journalism Network. Brian Palmer contributed research and reporting to this article.

In early August of 1973, a short article titled “Judge Rules Steamfitters Must Admit Minorities” ran on page six of the Amsterdam News. It explained that the Steamfitters Local 638 “must admit Black and Spanish-surnamed applicants exclusively for ninety days effective August 6.” The brief story mentions that “Fight Back, Inc., headed by Jim Haughton, is a local community-based organization that has been effective in getting construction jobs for Blacks, Spanish-surnamed, and other minorities in New York City.”

Two years earlier, we published an article titled “Black steamfitters demand equal chance to work here,” which reported that the “members of Fight Back vow not to allow the Steamfitters Union to proceed on any job uptown unless the workers are integrated.

“We are tired of the discriminatory practice of the Steamfitters union and of all the trade unions which make it a practice to hire Black and Puerto Rican workers last and lay them off as soon as the work slows down,” Haughton was quoted as saying.

Those two articles, which ran 18 months apart, highlight the struggles that New Yorkers of color faced in integrating the skilled and construction trades and their unions. But they also highlight just how effective Fight Back (also known as Harlem Fight Back) and its longtime leader James “Jim” Haughton, were, along with many others, in ensuring that workers of color received their fair share.

The Brooklyn-born Haughton served as an assistant to the legendary labor leader A. Philip Randolph at the Negro American Labor Council before forming the Harlem Unemployment Center, which would later become Fight Back.

“Jim’s philosophy was, if we can’t work here, nobody could,” Lavon Chambers, a former Fight Back organizer, union organizer and currently the executive director of Pathways to Apprenticeship, told the AmNews in a lengthy interview.

“Jim always had a vision. He didn’t really live long enough to actually see. But Jim had a vision of what would happen if the community and labor ever got together,” Chambers added. Their power would be unstoppable.

“The struggle for economic improvement,” Haughton wrote in a 1979 AmNews op-ed, “must come from below, from the workers.”

As an organizer and activist for more than 30 years, Haughton was at the forefront of the group of activists and organizations forcing both developers and local unions to hire workers of color, especially on job sites in

their communities. A 1977 AmNews profile said “Haughton and the construction workers he calls his brothers with a winning sincerity, have been on the picket lines that have sometimes deteriorated into bloody brawls at Harlem Hospital, Downstate Medical Center... and almost every other confrontation with the unions and contractors who control the industry.”

Many activists and organizations played a role in the integration of New York’s building and construction trades, but Haughton and Fight Back were, in many ways, the furnace that forged the growing equality that those in the skilled trades now enjoy.

“As Fightback’s [sic] reputation has grown,” the 1977 AMNews profile states, “organizations modeled after its aggressive approach have sprung up in Seattle, Detroit, and Washington.”

The Civil Rights Act and federal non discrimination laws and executive orders passed in the mid-20th century guaranteed, at least on paper, that people of color should be able to get work on construction sites, but the reality of de facto segregation continued, even in the “liberal” North.

“They’re building highways in communities of color or new housing projects or community centers [and] you’re bringing this racially exclusive white workforce into communities of color,” said Dr. Trevor Griffey of UCLA in an interview.

“And people can see from their doorsteps. ‘Oh, I can’t even get a job in my own neighborhood,’” he added.

What was clear to Haughton and other activists in the 1960s, and became gospel in the following decades, was that without community pressure and direct action, nothing was going to change for Black workers.

But what does direct action look like? The AmNews interviewed two former Fight Back activists who detailed both their experiences and the impact Haughton had on them and the entire industry.

Born and raised in Harlem, Chambers had recently come out of the Army and lost his job as a video editor when he first wandered into the offices of Harlem Fight Back on 125th Street in the early 1990s.

“When I came out of the Army, [I] didn’t really know what to do with my life. But I knew I didn’t want to go back to hanging with my ‘friends.’A lot of them were cool, but it didn’t really lead me to anything good. I inadvertently heard about an organization in my neighborhood called Harlem Fight Back,” Chambers said in an interview.

It is there where he met Jim Haughton, who took a liking to Chambers and gave him books

to read, including “The Miseducation of the Negro.” Chambers warmly recalled the first few weeks he spent in those offices listening to the organization’s leaders and members talk about politics “as opposed to standing on the corner, talking to people who are selling drugs, or, committing acts of violence.”

Chambers quickly learned, however, that Haughton and his colleagues were more than just talk.

“One day, they’re talking, ‘Hey, Lavon, you want to come with us on the Shape?’ I’m like, ‘What’s the Shape?’” he recalled. They told him, “‘There’s this job over here. And they won’t hire people from the community. And we’re going to go shut it down.’ What do you mean, you want to shut it down? ‘We’re just

going to shut it down [using] civil disobedience’. And I thought these people were foolish.

“They’re talking about, ‘You’re gonna go to the site, where all these white folks [are] there, and you’re gonna shut your site down.’ I thought it was foolishness. But I went.”

And that day would change his life just as it had for so many others. Chambers described getting in one of several vans that transported Fight Back members to a nearby construction site.

The van pulled up and “we all ran in the building. And there wasn’t any violence. We just went in there,” Chambers recalled. “It was coordinated, like a tactical military effort. We just hit every floor. We told

Continued from page S6

people with force, ‘There’s a labor dispute, exit the building now!’” And to his surprise the workers... listened. They all left the building and lined up across the street while Fight Back leaders spoke with their supervisors who promised that several of their members would return tomorrow and be allowed to work.

“And I remember I got really emotional. This was like a religious experience to me,” Chambers said. That experience would light a fire in him to become more active in the organization. “Jim used to always talk about building an army. Like not the army in the sense of fighting,” but an army made up of the community to fight for equal opportunities to work.

Jerome Meadows also joined Fight Back in his 20s after working as a drug dealer for the infamous Nicky Barnes. A friend told him about the organization and how it was helping people get construction work, an attractive alternative to the messenger work he was doing after leaving the drug trade behind.

When he explained his checkered past, Fight Back organizers still welcomed him and he, too, joined the direct actions to stop construction sites.

Meadows didn’t get work immediately, but he stayed with Fight Back, and within a few months he was earning $18 an hour working in demolition. But he also saw that “we really wasn’t accepted with open arms” at a job site that were otherwise lily white.

On some of his first jobs, Meadows said, they called him “derogatory names. They would write ‘Nigger go home,’ nigger this, nigger that in the bathroom.” He added that white workers left “ropes with with monkeys hanging [from them]. It was terrible.”

But Meadows and Chambers endured the abuse and racism they encountered and climbed the ranks, eventually joining Local 79 at Haughton’s encouragement.

During his time with Fight Back, and later within Local 79, Meadows recalled seeing a transformation happen within the real estate development community in New York City due at least in part to the pressure of the ongoing direct action work of Fight Back and other organizations.

“If you’re building in these communities, a certain amount of work must go to people in the community,” Meadows said of the organization’s approach. Once the developers decided to start hiring minorities, he added, “they started putting [us] on [as] project managers. Women started getting key positions.”

Even within the union, which Chambers joined at Houghton’s urging after several years of working with Fight Back, he recalled that his early days as an organizer were anything but pleasant.

“I spent a few years there feeling like a hated man,” he said. “People did not like me. People were not nice to me. But there were some people there who had nothing in common with me but they took me under their wing. And they helped protect me. And it gave me time to be able to work on things.”

The hard work of Haughton, Chambers, Meadows, and the thousands of activists and union members and leaders helped transform the landscape of New York organized labor.

Chambers says that Local 79 was more than 90% white in the mid 1990s and based on public filings from Local 79 required by the government. Now, the union is comprised of than 70% women and people of color.

Getting to this point has not been easy.

“There has been a complete paradigm shift within the leadership of the building trades, in terms of the way they view diversity,” Gary LaBarbera, President of the New York State and the New York City Building and Construction Trades Councils, said in an interview with the AmNews. “I’m very proud of what the leadership of these individual unions have taken on and collaboratively we have made a real decision, a conscious decision to expand that increase opportunity and further diversify the building trades.

“When you look at the apprentices that are coming in, over 75% identify as a minority. And so this has been a conscious effort by the building trades affiliates and the Building Trades Council, to once and for all move past that criticism, and we have committed ourselves to working with marginalized and underserved communities.”

Chambers acknowledged that the legacy of trade unions excluding workers of color was well known. “But we also understand that at some point, somebody needs to build an army of like-minded folks....And once again, I need to stress this. I don’t want you to write something that [makes] people say, ‘Oh, Lavon Chambers says that the racism is over?’ No, that’s not what I’m saying. I don’t know anywhere in America that I could actually say that. But what I am saying is that while things have changed so much, that there’s an opportunity to help people,” he added.

Our final installment will examine what programs are working to solve the access problem for workers of color and the impact they are having on the lives of young people.

This series was made possible by a grant from the Solutions Journalism Network. Brian Palmer contributed research and reporting to this article.

For most New Yorkers, high school doesn’t involve welding or building bathrooms, but for the hundreds of students at the Bronx Design and Construction Academy, and the many schools like it, what students learn in their teen years puts them on a direct path to lucrative, middle class jobs.

Career and Technical Education (CTE) is the modern evolution of what used to be called, sometimes derisively, vocational education. While more than 60,000 CTE students each year in NYC gain a practical education in a trade, they also learn advanced math and the skills that will power the Green Economy.

“I always thought that construction workers were dirty,” said Bronx Design and Construction Academy senior Issa Samake in an interview with the AmNews Before attending the school, he believed that construction workers and those in the skilled trades “were doing a lot of dirty work, for not enough pay. I felt like people who go into construction are the people who don’t have any other choices in life— they have to go to construction to make ends meet,” he added.

A first-generation American whose parents hail from Mali, Samake, along with his classmates, takes traditional academic and even Advanced Placement classes while focusing on one of five areas: Plumbing, Electrical, Carpentry, Architecture, and HVAC. Soon after starting his first year, Samake’s opinions about the skilled trades began to change.

“I see it as hard work, and I also see it as a skill. And you need to be smart,” he said. “One of the first things I learned when I came to the school was that no matter what trade you do, what type of construction you do...you’re gonna have to be good at math.” He has focused on plumbing in high school and, thanks to the school’s state-of-theart facilities, has learned how to build and repair bathrooms for home and commercial spaces, among other skills.

In 2020, CTE schools in New York City had an 86% graduation rate, according to the Department of Education, compared to 79% for the system overall.

“There is a huge focus on interdisciplinary instruction,” said Venkatesh Harini, executive director of Career Connected Learning in the NYC Public Schools. “We’re trying to, at all points in time, seamlessly integrate the academic requirements with the technical requirements, so that ultimately, when a student graduates from our school system, they have a core set of skills that make them both college- and career-ready soon after they graduate.”

She said that schools Chancellor David Banks “has emphasized the importance of

reimagining learning so that we are connecting a young person’s passion and purpose to long-term economic security.”

For decades, American educators have preached that the primary path to economic security is a four-year college degree, and many Americans still pursue that track. But the huge demand in skilled trades like plumbing means that not every student has to straddle themselves with the kind of college debt that even President Biden is trying to wipe out.

“College is supposed to prepare individuals for their chosen career. If a student wants to be an engineer or go into

the medical field, a step to those industries [is] college, so they have to go that pathway. However, for many other careers, the pathway is not college,” said Anthony Johnson, one of Samake’s teachers, in an interview. “They can [go] from high school…directly into a career.”

Johnson noted that some individuals are unemployed after finishing college, and their degree has nothing to do with the career they choose. “So what was the value of going to college for that person?”

For students like Samake, an internship is an important step in their path. As part of his education, he spent months working at Westchester Square Plumbing Supply. Bob Bieder’s family has run

the company for 99 years and he believes that being an industry partner by offering internships has huge benefits for the students, the community, and his business.

“The kids that have come from this program have been amazing,” Bieder said in an interview. “This program affords them the opportunity to make a great living. Almost all have gone on to jobs in the industry and many of the kids come from lower-income areas.”

He also noted that “there is a huge need for qualified people. Right now, I have so many contractors who tell me on a regular basis that they can’t find anyone to work for them.” Bieder said with pride that many of his former interns now come through his doors as customers who are working in the industry.

Being qualified as a skilled tradesperson can make a huge difference to the career prospects of many students.

“We have students who realize that ‘I’m struggling where I live, and one way to improve my circumstances is to learn this trade so that I could become employed and hopefully take care of myself,’” said Johnson.

“The positive is, students are able to begin their careers at 18, which will lead to them supporting themselves. As much as possible, we try to steer our students toward the high-income earning opportunities if they qualify. Unfortunately, we do not get enough students to qualify,” he added.

Johnson said that his greatest feeling of success as a teacher comes when his former students, many of whom are under 30, return to invite him to the housewarming party for their recently purchased homes.

What about those who don’t receive the opportunity to learn a trade while still in high school?

For much of the 20th century, the way into a skilled trade union was essential through birth: A family or friend connection was the only way into an apprenticeship program, which led many local unions, including some of those in New York, to being lily white.

“We don’t create jobs, we create careers,” said Gary LaBarbera, president of the New York State and the New York City Building and Construction Trades Councils, in an interview with the AmNews.

His organization provides programs that, in addition to working with New York high school students, help several groups, including veterans and those who have been affected by the criminal justice system and others, prepare to become skilled trade apprentices and join those unions.

While many unions have had long histories of exclusion, LaBarbera highlighted the forward-thinking choices that his members have taken to create change. The

programs they offer train between 600 and 800 people a year, which make up around 40% of new apprentices in New York.

“Why it so vital to reach into marginalized or underserved communities is because we believe the goal of organized labor is to lift people out of poverty into the middle class, and to build a stronger middle class and to create an opportunity for people to have family-sustaining careers where they can also have good medical coverage for themselves and their families, and ultimately have retirement security,” LaBarbera said. “This is only offered through the unionized construction industry and through our apprentice programs.”

Jamahl Humbert, Jr. is an example of how such programs make a difference. He wakes up at 4 in the morning to travel more than 90 minutes from his home in Staten Island to the International Association of Bridge, Structural, Ornamental, and Reinforcing Ironworkers Local 580 Training Facility in Long Island City. The nondescript structure could easily be mistaken for an office building, but once inside, it becomes clear that this is a place where folks work with their hands.

Humbert joined the program because it offered what he described as a “lifetime skill.” The program offers the ability to get on a pre-apprentice track that is otherwise much more challenging to get into.

“I think that for a lot of people, construction skills is definitely the way to go,” Humbert said.

Nearly 90% of the participants in the Edward J. Malloy Initiative for Construction Skills are members of a minority community, said Nicole Bertrán, the organization’s executive vice president, in an interview. In addition, “80% of the graduates we place into unionized, apprenticeship opportunities stay and complete their apprenticeship and become journeypersons. That’s really important because a lot of the criticism or critique of programs like construction skills is that ‘you can get them into the apprenticeship, but then they never finish,’ which isn’t true,” she said.

Programs like these not only pay trainees and apprentices to learn; those students leave the programs debt-free, unlike the tens of millions of Americans struggling with college student loan debt.

While these initiatives and ones like it in New York are making a real impact, there is still much work to be done on the national level. According to a recently released report by the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, which examined all registered apprenticeship programs (including those outside the construction and skilled trades), Black apprentices are underrepresented across the country, making up just 9% of apprentices, even though Black Americans make up more than 12%

of the national workforce. However, this is still an improvement from 1960, when Black workers made up only 3.3% of ap prentices in registered programs.

es are least likely to complete their programs and have the lowest earnings. Justin Nalley, a senior policy analyst at the Joint Center, attri butes this in part to the high concentration of Black apprentices in the South.

labor standards for workers and employ ers,” he said in an interview with the AmNews are only earning 64 cents on the dollar compared to other areas in the country.”

Real estate developer William Wallace IV of the Continuum Company, along with many of those interviewed for this article, attributed the lack of full representation in the skilled construction and construction trades to the lack of use of unionized labor. A third-generation Harlemite, Wallace is perhaps unusual among his peers, many of whom seem to only have their eyes on the ledger books, for his fierce

trades have become far more inclusive, Wallace emphasized that “the amount of work that unions have been receiving, particularly for residential work in New York, has been enormously diminished. It used to be a 100% union town and that has changed.”

Being a developer of color in an industry with so few peers is also a motivating reason behind why Wallace is so pro-union.

“My commitment is to be sure that people

nity to build,” he said. “I think you don’t find that personal kind of political commitment because there’s not [many] people of color

LaBarbera said that while his unions do ing developers, “there are developers out there only committed to one thing, and that’s profit. And I don’t believe they’re really, truly committed to diversity; I don’t believe they’re really, truly committed to

struction is everywhere—we are born in a hospital that was built and constructed, we go back to a home or an apartment that was built and constructed,” Wallace said. “To not be [able] to be part of that is criminal.”