Union Matters

A day for mothers

The heart of your family, the soul of a union

With Mother’s Day approaching, there will be countless tributes and remembrances dedicated to the first person who welcomed us into the world after a nine-month wait. Over the years, some acknowledgments have been happy; some, unfortunately sad; but all make an important statement of fact: “Mom made a difference in my life.”

Maya Angelou said: “There is no influence as powerful as that of a mother.” Former President Barack Obama credits his mother with “What is best in me I owe to her.” Michael Jordan called his mother “his root, my foundation,” while Stevie Wonder said, “Mama was my greatest teacher, a teacher of compassion, love and fearlessness.”

Clearly, we know that mothers have a huge impact not only on their own children, but on other peoples’ kids as well. Throughout history, mothers worldwide have played roles from warrior to waitress for their offspring and those of others. In our country, from protesting our involvement in Vietnam to drunkdriving to Black Lives Matter—and so many more issues, mothers have led the marches and held the banners: Mothers Against Drunk Driving, Moms Demand Action, Moms United for Black Lives, Another Mother for Peace, Wall of Moms, and Harlem Mothers S.A.V.E., to name just a few. In each, mothers made a difference for the better, fueled by their personal pain and instinctive empathy.

The same is true of the labor movement. Over the past decade, about 60% of newly organizing workers have been women. Women now are also the faces of some of the largest labor movements in years. For example, after the death of AFL-CIO president and prominent national union leader Richard Trumka in 2021, Liz Shuler, longtime labor leader and supporter of Moms Rising Together, took over as president—marking the first time a woman took the helm of the largest and most powerful federation of labor unions in the country. The pandemic created an opportunity for new movements in industries that haven’t organized before—movements also led by women. In 2021, the gender gap in union representation narrowed: About 10.6% of men are members of a union, compared with 9.9 percent of women, a proximity not achieved since statistics were recorded in the 1980s.

Among the factors contributing to this narrowing gap is that unions can be a route to equal pay. Especially with approximately 25% of households nationwide now headed by a single parent—80% of whom are women—and 21% of children living pri-

marily with a single mother, unions provide the much-needed pathway to worker safeguards and benefits that are of particular concern to women, such as maternity leave, childcare accommodations, paid vacations, and so much more. In fact, studies have found that unionization tends to benefit women more than men, especially in eliminating pay disparity.

Trying to fight the fight without strong union backing can be a most exhausting, costly, and disappointing struggle. Just ask another hardworking Alabama mom, Lilly Ledbetter, who unbeknownst to her, worked for over two decades in a Goodyear tire factory for lower wages because of her gender than those doing similar work. It was only when she was cleaning out her locker upon retirement that she discovered she hadn’t been paid equally, thanks to an anonymous note slipped into her locker.

Ledbetter went on to fight the battle for pay equality for years, first filing a formal complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and later initiating a lawsuit under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Equal Pay Act of 1963. Although a jury initially awarded her compensation, Goodyear appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, which overturned the ruling on the grounds that her claim was filed too late— outside of the 180 days from first being employed as required by law.

She received nothing, but she persisted, and in 2009, President Obama, just nine days after being sworn into office, signed into law his first piece of legislation: the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act.

In my own union, Local 237, we fought and won an historic gender-based class action lawsuit, too. We filed against New York City on behalf of school safety agents—70% of whom are women, mostly Black and Latina—performing similar duties as peace officers working for other City agencies, 70% of whom are men—but who earn approximately $7,000 more per year than their counterparts working in public schools.

Our union may have brought the legal action against the city but it was three school safety agents—Patricia Williams, Bernice Christopher, and the late Corinthians Andrews, all mothers—who made personal sacrifices and persevered throughout years of court wrangling that resulted in equal pay for not only their co-workers, but for retirees as well.

As we remember Mom on her big day, let’s also think about the contributions that all moms make to help the world become a better place both within and beyond their own families. Especially in the labor movement, mothers will always hold a special place. They are the soul. It’s the Sisterhood alongside the Brotherhood, working in partnership for all families, helping them not just survive but thrive.

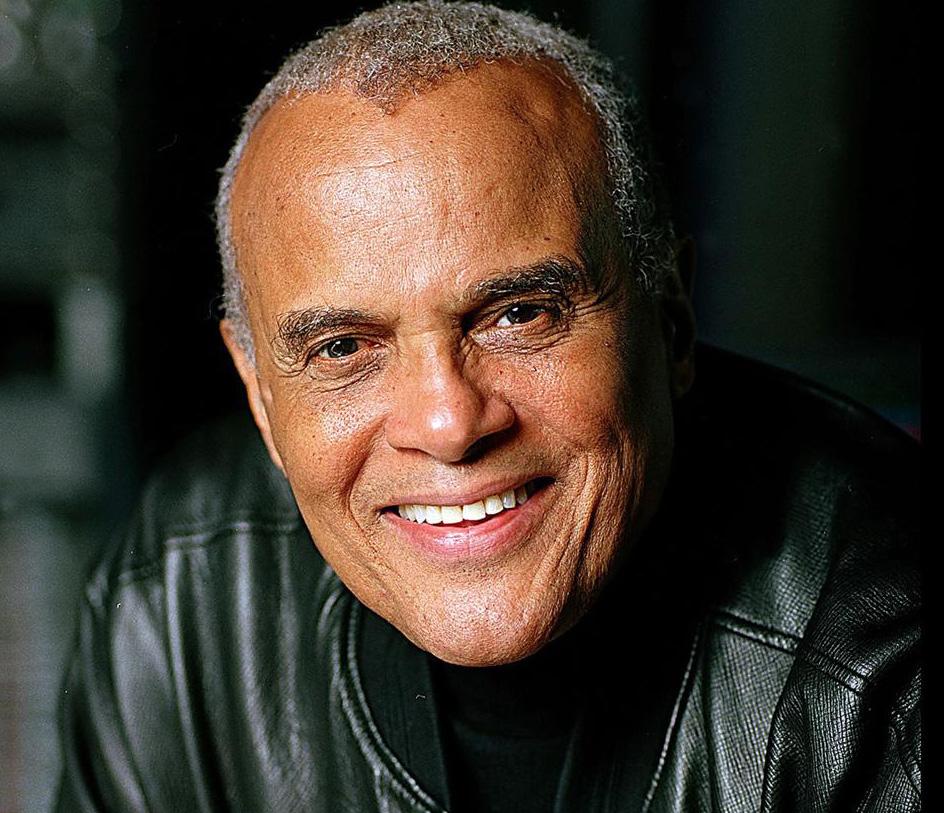

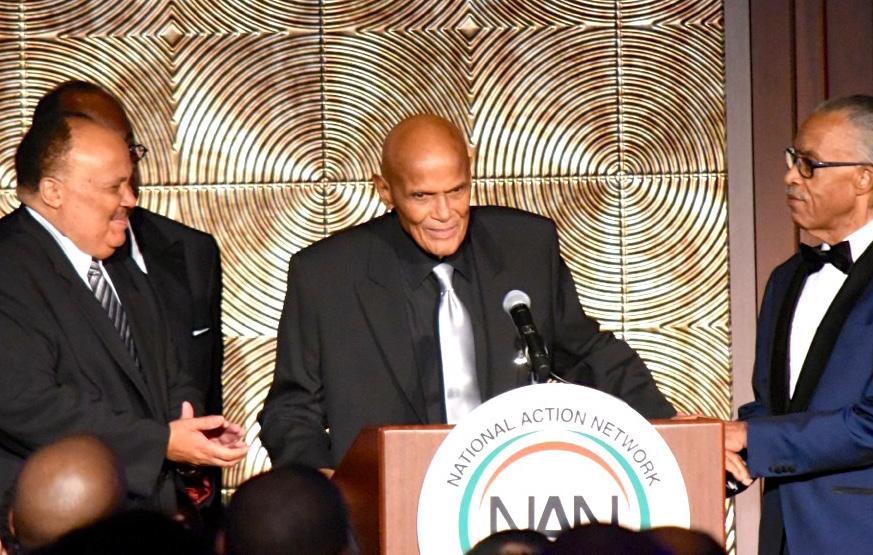

Harry Belafonte—the activist artist who influenced the labor movement

By KAREN JUANITA CARRILLO Amsterdam News StaffThe passing of legendary artist and political activist Harry Belafonte has been felt throughout the labor movement. Beyond his celebrity, Belafonte was a major supporter of the Civil Rights Movement––and, by extension, its ties to labor activism.

Actors’ Equity, the union that represents stage, theater, and film performers, tweeted that “Equity mourns the passing of legendary actor, musician, and activist Harry Belafonte. Belafonte received the union’s Paul Robeson Award in recognition of his extensive civil rights and social justice advocacy. He will be deeply missed.”

In a statement about the actor, who once served as president of the union’s not-for-profit culture-based project, Bread & Roses, 1199SEIU President George Gresham said, “1199SEIU healthcare workers mourn the passing of our beloved ‘Mr. B.’ Harry Belafonte was a pioneering artist, social justice warrior, and healthcare champion. His lifelong commitment to advancing freedom and equality—often risking his own career and livelihood in the process—is testament to his character and courage.

“I cannot think of a social justice

movement in my lifetime that didn’t have Mr. B behind it in some way.” Belafonte’s extensive civil rights and social justice advocacy turned him into a great example of how celebrity can be used to further economic justice. Of course, the actor’s major role of supporting Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his family stands in the forefront. But Belafonte’s work with King was only one part of his activism.

When King was assassinated in 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee, he had been championing a strike by some 1,300 African American sanitation workers. King’s Poor People’s Campaign saw him advocate for fair wages and demand economic reforms to help end poverty. Demanding economic reforms that would help low-wage and exploited workers was a challenge Belafonte also pursued. When he took up the mantle of supporting King’s work in the 1950s, it was not his first foray into progressive politics. Belafonte had long admired the stance of the activist/actor Paul Robeson, who had been branded a communist because of his labor union activism and his trips to the Marxist-Leninist–oriented Soviet Union.

Even after he was blacklisted by Wisconsin Sen. Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s, Belafonte remained enchanted

See UNION continued on next page

Continued from page 10

by Robeson’s forthright stature and came to look at the way he had combined art and activism as an important roadmap to follow.

Belafonte became as much of an activist artist as Robeson. As recently as 2013, LaborPress reported that Belafonte told an audience in Queens, “We’ve got to get outside of the box. The way to get outside the box is to radicalize the schools, radicalize unions, radicalize people, radicalize religion.

“Radical doesn’t mean violence,” Belafonte cautioned. “Radicalize doesn’t mean to hurt, harm, or disrupt. The word ‘radical’ means different from the norm.”

Belafonte had said that he thought organized labor was not fighting for its rights with the urgency that it needed. “I do genuinely believe that the labor movement has got to understand that it has got to stop behaving as the victim, and to begin behaving like the masters of destiny,” he is reported to have said.

The actor often spoke out in support of labor struggles he came across. He was vocal in supporting strikes by unions like Local 802 - American Federation of Musicians when it waged a Justice for Jazz Artists campaign in 2013 to gain retirement and recording protections for musicians who

often worked in clubs and in studios their whole lives but retired and found themselves living in poverty.

Belafonte had been a supporter of the labor organizing teachings of Tennessee’s Highlander Folk School. Highlander––which styled itself a “movement-building” center––was famous for holding seminars and classes for civil rights organizers in the 1950s. It also sponsored regular lectures about labor economics, union organizing, and labor history.

Belafonte wholeheartedly believed in Highlander’s movement-building philosophy. He went on to work with and become a confidante of Long Beach, California, labor

organizer Ernest McBride; United Automobile Workers (UAW) President Walter Reuther; Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters President A. Philip Randolph; and Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers union.

In 1959, Belafonte formed part of a triumvirate with baseball star Jackie Robinson and actor Sidney Poitier that promoted African nationalism and trade union organizing. The three helped fund the efforts of Kenya’s Justice Minister Tom Mboya to put together Project Air Lift Africa, which brought 81 Kenyan students to the U.S. to attend college. “I, along with Jackie Robinson and fellow artist Sidney Poitier, agreed to help implement Tom’s vision,” Belafon-

te wrote in the foreword to the 2009 book “Airlift to America. How Barack Obama, Sr., John F. Kennedy, Tom Mboya, and 800 East African Students Changed Their World and Ours” by Tom Shachtman, which details the efforts to get Project Air Lift Africa up and running.

“I wrote letters and gave concerts to raise funds to charter airplanes that would bring young people from East Africa who had successfully applied for scholarships at many of our colleges and universities,” Belafonte said. “The concerts did well and the response to the mailing was extraordinary. Postal workers from the Bronx sent oneand two-dollar contributions with letters explaining how important they realized the airlift would be for the future of a free Africa. Many people from across America sent their precious contributions, few exceeding twenty-five dollars. It was an amazing outpouring of belief in a dream.”

Project Air Lift Africa united Kenyan trade unionism with the organizing work of the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU). Its efforts helped Kenyan students gain important labor, governmental, and nation-building skills as the country moved toward independence from Britain.

Belafonte the celebrity will be remembered for having leveraged the power of his fame to help improve the social and economic conditions of working people.

Harry Belafonte, versatile entertainer, civil and human rights activist, dead at 96

By HERB BOYD Special to

By HERB BOYD Special to

the AmNews

Whether on film, in song, at the podium, or on the ramparts, there was an artistic and political consistency in Harry Belafonte’s life. In the tradition of his idol Paul Robeson, Belafonte was unflinching in standing up for the downtrodden, expressing a relentless fight for civil and human rights. That principled life of conviction and speaking truth to power came to an end on Tuesday morning, according to his publicist Ken Sunshine, who said Belafonte died of congestive heart failure. He was 96.

Belafonte first attained worldwide celebrity as a calypso singer, with millions singing along with his version of “Day-O,” a song capturing laborers in banana production, although he was born in Harlem, on March 1, 1927. The popularity of that song in 1956 was just a harbinger of his phenomenal accomplishments, particularly as a singer, actor, and activist.

In 1944, after dropping out of high school, Belafonte enlisted in the US Navy. Perhaps the most rewarding aspect of his military tenure was the number of worldly wise men he met who gave him some lessons on politics, especially the complexities of colonialism, racism, imperialism, and fascism. These encounters proved instructive and forged his contact with militant activists upon his return to civilian life.

“Even though he was known internationally for his voice and his skills as an actor, I knew him as a civil rights activist and personally believe if there was no Harry Belafonte, there would be no Martin Luther King,” said Charles B. Rangel, former representative to Congress and a friend and ally of Harry Belafonte. “He was so dedicated to King and the march from Selma to Montgomery, not only financing but organizing and bringing people to Montgomery, including me, who didn’t intend to march 54 miles but wound up doing it anyway.

“He was able to bring cameras to focus on that march. After Bloody Sunday, which was a few weeks earlier, a lot of people worried the march would be a failure, but Harry was the one who told everybody ‘we have to do it.’”

Rangel concluded, “I met with him at his home recently and he was frail and his voice was weak, but he was talking about the things we had to do to bring this nation past the polarization and hatred that exists. I never found anyone as committed personally to the Civil Rights Movement, even at the expense to his professional career and his family. He was talking about what we have to do next.”

Much of Belafonte’s productive life is captured in his memoir “My Song” with Michael Shnayerson (2011). The hefty tome is split between Belafonte the actor and Belafonte the activist, and even some of his most ardent fans were surprised at just how much of his time, energy, and resources were devoted to civil and human rights struggles.

Belafonte patterned his life and social commitments after his mentor and idol Robeson, rarely ever compromising his artistic and political integrity. In fact, his art and politics were so tightly interwoven that they are as immutably consistent and unimpeachable as they are inseparably linked.

One of the most memorable moments in his life was when he and his lifelong friend Sidney Poitier were couriers during the civil rights days, delivering funds to the embattled Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) field workers in Mississippi. His connection to the Harlem community resonates in several significant ways, perhaps most incipiently when he was a member of the American Negro Theater, where he and Poitier received early tutelage in stage and screen.

A few years ago, a branch of the New York Public Library (NYPL) was named in his honor, an occasion that he shared with Cicely Tyson. Some of this papers and memora-

bilia are housed at the Schomburg Center. It isn’t easy to find one passage that summarizes his steadfast conviction and unwavering commitment to freedom, justice, and equality, but this one may service: “Race was the cutting edge in everything I did,” he said about his role as a Black entertainer. “To let myself be turned into an object of ridicule would undermine not just my stage persona, but my purpose as well.”

The steadfastness and outspokenness Belafonte evinced as a young man continued into the august of his years, even criticizing President Obama and calling President Bush the “greatest terrorist in the world.” He was often unsparing in discussing the need for the younger generation to commit themselves more to voter registration and to take a stand against the rampant police abuse.

Robeson, in his final words as Othello, said he had done the state some service. The same can be said and underscored in the life and legacy of Harry Belafonte.