The Making of an African Waterscape

Yoruba Spirituality, Colonial Narratives and Contemporary Urban Resilience in Lagos’ Battle against Climate Change

UP2042040

Front Cover: NLÉ and Zoohaus/Inteligencias Colectivas

The Making of an African Waterscape: Yoruba Spirituality, Colonial Narratives, and Contemporary Urban Resilience in Lagos’ Battle against Climate Change

Dissertation Personal Tutor: Leago Madumo

Module Coordinator: Elizabeth Tuson

BA (Hons) Architecture

History and Theory of Architecture: Dissertation

January 2024

Graduating Class of 2024

Word Count (5332) does not include references, footnotes, and other auxiliary information that further clarifies points made in the essay.

University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth School of Architecture

Acknowledgements

I want to extend my heartfelt gratitude to my parents for instilling in me a profound appreciation for my heritage, which inspired the topic of this study.

I would also like to give special thanks to my sisters, who have given me unwavering support and encouragement throughout my undergraduate journey.

Lastly, I express my deep appreciation to my dissertation tutor, Leago Madumo, for her invaluable guidance and support during the completion of this dissertation.

Author’s Declaration

I, Elisabeth Ololade Ajayi, hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the dissertation.

List of Figures

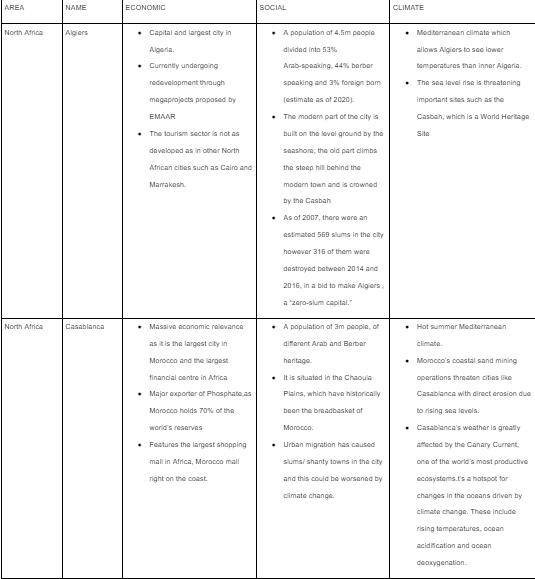

Figure 1: NLÉ and Zoohaus/Inteligencias Colectivas

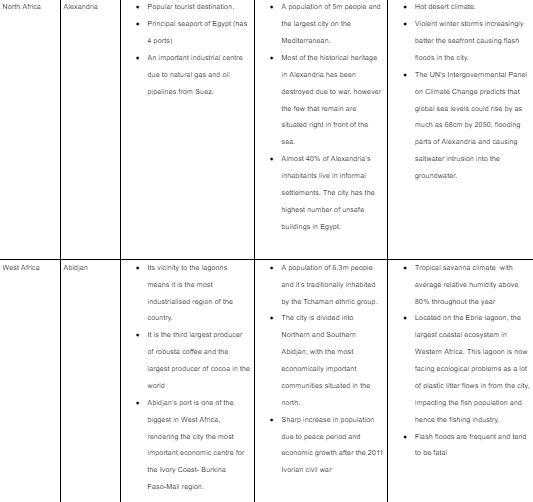

Figure 2: Lagos Lagoon from State House, 1968 ( Source: Delfcampe.net)

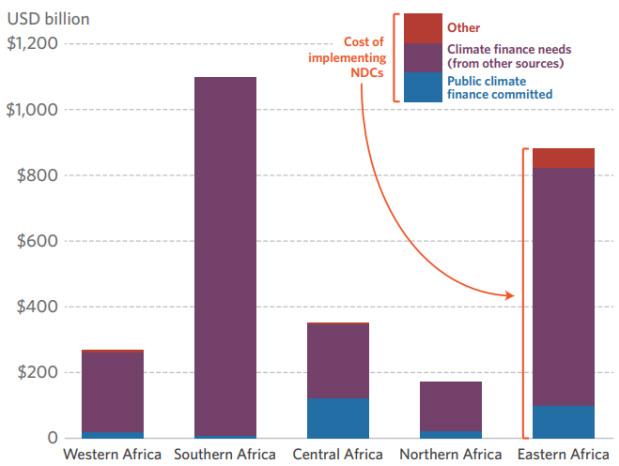

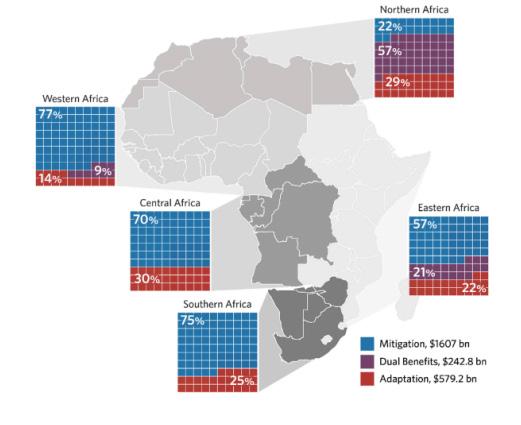

Figure 3: Estimated climate finance needs in Africa by region ( Source: Guzman et al.,2022)

Figure 4: Estimated climate finance needs in Africa by region ( Source: Guzman et al.,2022)

Figure 5: Ishikawa diagram (Source: Wong et al., 2016)

Figure 6: Aerial view of Lagos, 1960s ( Source: Delfcampe.net)

Figure 7: Walking distance from Ile-Ife, ancient origin of the Awori, to Isheri (Source: Google Maps)

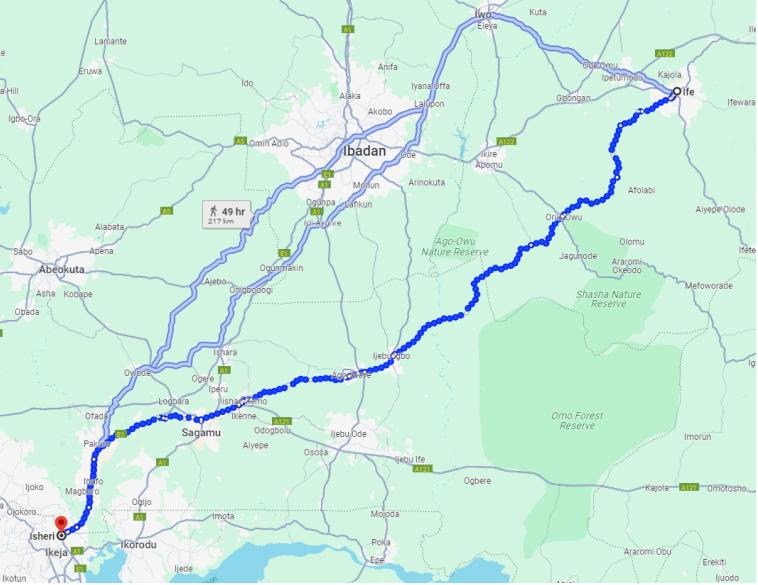

Figure 8: Worshippers at the Osun Osogbo Grove (Source: Premium Times Nigeria)

Figure 9: Devotees at the Yemoja Festival in Ibadan, Nigeria (Source: Al Jazeera)

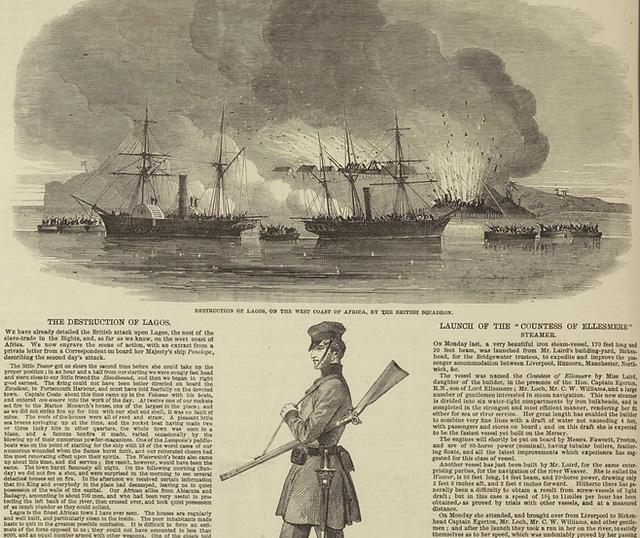

Figure 10: “British Men o’ War Attacked by the King of Lagos” (James George Philp, 1851)

Figure 11: A newspaper article on the destruction of Lagos (Source:Royal Marines History)

Figure 12: Lagos’ built up area and its four main quarters in the 1890s (Source: The National Archives)

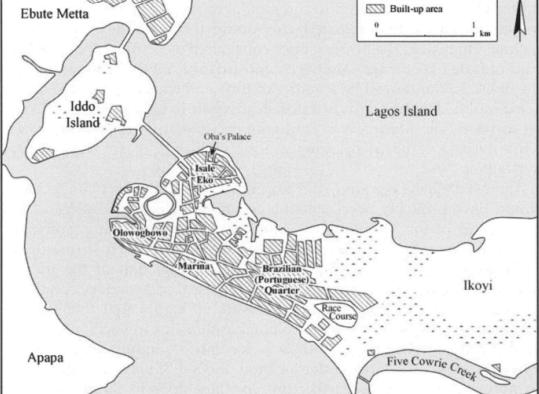

Figure 13: Map of Lagos in the 19th century (Source: Lagos Executive Commissioner of the Colony and Indian Exhibition 1886)

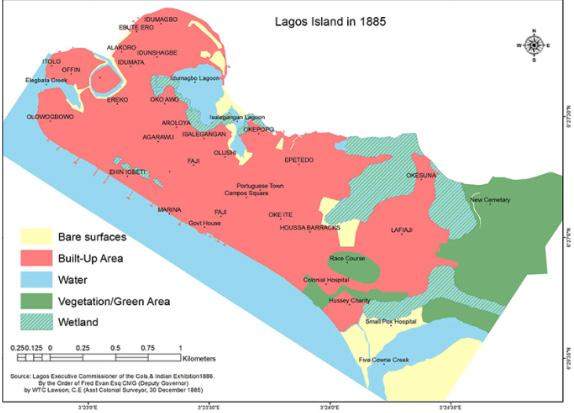

Figure 14: France/Paris (Source: Google Images)

Figure 15: Portugal /Lisbon (Source: Google Images)

Figure 16:UK/London (Source: Google Images)

Figure 17: Nigeria/Ile-Ife (Source: Google Images)

Figure 18: Mali/Timbuktu (Source: Google Images).

Figure 19: Ghana/Kumasi (Source: Google Images)

Figure 20: Carter Bridge street scene, 1950s (Source: Delcampe.net)

Figure 21: The Lagos Railway, 1900s (Source: Delcampe.net)

Figure 22: Makoko and the Third Mainland Bridge ( Source: Unequal Scenes)

Figure 23: The Lekki Conservation Centre (Source: Atlas Obscura)

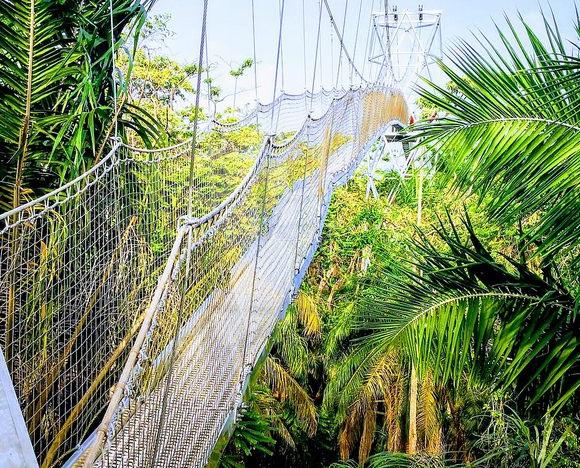

Figure 24: Banana Island, one of the richest neighbourhoods in Lagos (Source: Nigeria Property Centre)

Figure 25: Bariga slum, Lagos (Source: Flickr)

Figure 26: Makoko, Lagos, can be navigated by boat (Source: AFP Photo)

Figure 27: A lady swimming amidst flooding on the Lekki-Epe Expressway, Lagos (Source: Punch Newspaper)

Figure 28: Traffic in flooded Lagos (source: The Guardian Nigeria)

Figure 29: Omu Creek, Lagos,2012 (Source: HumAngle Media)

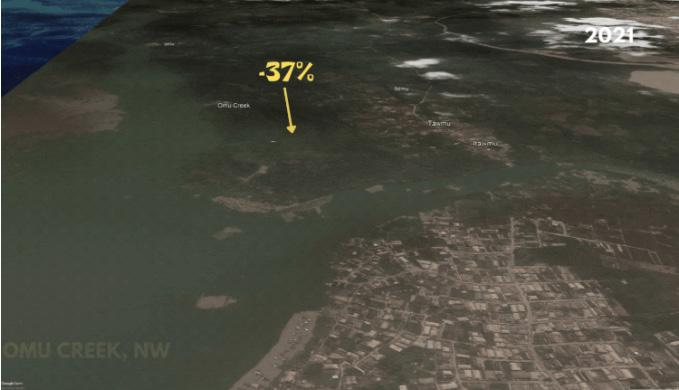

Figure 30: Omu Creek, Lagos, 2021 (Source: HumAngle Media)

Figure 31: A rendered image of Eko Atlantic City (Source: Eko Atlantic)

Figure 32: Eko Atlantic’s land reclamation phase (Source: Eko Atlantic)

Figure 33: Detailed cross-section of the Makoko Floating School ( Source: Dezeen)

Figure 34: The collapsed Makoko Floating School ( Source: Dezeen)

Figure 35: A Makoko Floating School Prototype ( Source: NLE Architects)

Figure 36: Functions of the sponge city ( Source: Polgar, 2021)

Figure 37: Tianjin Wetland Park, China ( Source: Turenscape)

Figure 38: Qnuli Stormwater Park, China( Source: Turenscape)

Figure 39:Lagos’ sponge city profile (Source: Arup Group)

Figure 40: Schoonschip, a floating community (Source: Space&Matter)

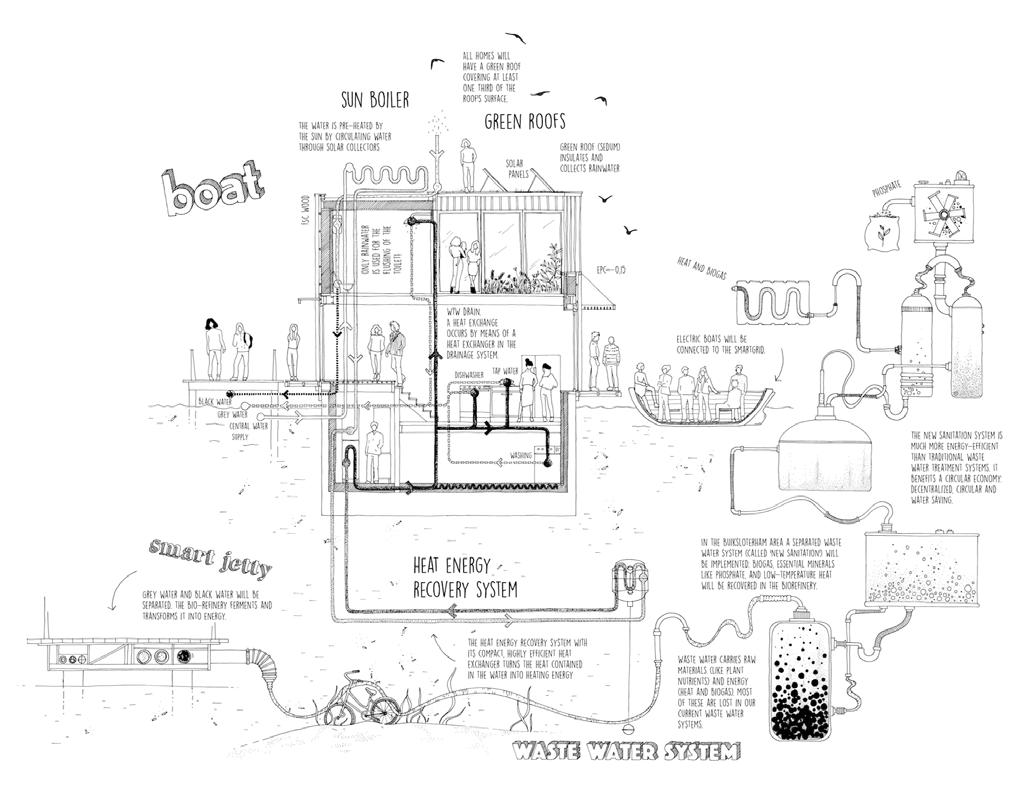

Figure 41: A diagrammatic drawing explaining Schoonschip’s energy systems (Source: Space&Matter)

Figure 42: A typical street scene in Lagos ( Source: Unsplash)

Abstract

“Omi tí kò sàn síwájú tí kò sàn séyìn Níí domi ògòdò àtomi ègbin”

“The stream that neither flows forward nor backwards is replete with dirt” - Yoruba proverb

(Orímóògùnjé, 2012)

According to the 2022 IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, all 12 major African coastal cities face high vulnerability to future sea level rise. This study concentrates on Lagos, the most populous metropolitan area in Sub-Saharan Africa. Despite being at the forefront of the country’s economic development, Lagos grapples with significant obstacles rooted in colonial legacies, rapid population growth and inadequate infrastructure systems struggling to keep pace. When these factors are compounded with the escalating threat of climate change , its exposure to the effects of rising sea levels is further amplified, posing destructive consequences to coastal communities without appropriate mitigation strategies. Despite the significant impacts this could bring to the continent, research funding on climate change in Nigeria and other African countries remains disproportionately inadequate compared to other parts of the world. The aim of this study is to analyse the environmental and climatic challenges facing Lagos through the lenses of history, socio-economics and urbanisation. The research considers cultural beliefs and attitudes to water, aiming to highlight the profound ways in which colonialism altered African perspectives surrounding the environment. Focusing on Lagos, a case study explored extensively by urban scholars, allows for a more detailed and comprehensive analysis of the subject topic, given the scarcity of research spanning across African regions. The significance of this study lies in emphasising practical efforts that have been initiated in Lagos and case studies of best practice that could be integrated in the city; as such, the tone of the discourse shifts from a purely pessimistic identification of the problem to a proactive exploration and documentation of potential remedies.

The Making of an African Waterscape: Yoruba Spirituality, Colonial

Narratives, and Contemporary Urban Resilience in Lagos’ Battle Against Climate

Change

1.1 Introduction

Elisabeth Ololade AjayiWater has historically held plural significance across cultures within the African continent. In certain instances, it is perceived as a dwelling place for mystical marine spirits while in others, it is worshipped as an emblem of purity and rebirth. Water symbolism features in many of life’s most pivotal moments: birth, marriage, initiation rituals, healing and even death (Kanu, 2022). Beyond its fundamental role in human existence, water facilitates the establishment of commercial trade routes and subsequently, the birth of civilizations. Significantly, the African coastline has long been a place where kingdoms and empires have flourished; the Oyo Empire near the Gulf of Guinea, Alexandria by the Mediterranean and Dar Es Salaam in Zanzibar, strategically positioned near Indian Ocean trade routes. Unfortunately, the African coastline has also been the entry point for slave traders and colonial masters during the darkest period within Africa’s past, spanning from the 19th to the 20th century. As articulated by postcolonial scholars, notably Homi Bhabha, this colonial past has given rise to a “hybrid” living condition, persistently dictating life on the coast by creating socio-economic divides that marginalise the poor and cluster wealthier individuals. Despite the cultural reverence for water and the enduring echoes of colonial influences, a looming spectre casts its shadow over the future of African coasts - climate change.

The aim of this study is to critically examine the environmental and climatic challenges facing African coastal cities through the lens of history, socio-economics and urbanisation. To streamline my research, I have chosen Lagos, the most populous urban conglomeration in Sub-Saharan Africa (Hamukoma et al., 2019) as the centre of this study. This study begins in Chapter 2 by delving into the colonial origins of Lagos’ urbanisation through an

in-depth historical and theoretical exploration. Chapter 3 examines how the ramifications of colonialism continue to shape the post-colonial Lagosian waterscape, where socio-economic divides are bridged by current threats of climate change. Consequently, in chapter 4, I draw knowledge from case studies of sustainable urban water management from two geographic locations, using them to make speculations about potential urban systems that could help Lagos effectively address climatic challenges. Finally in chapter 5, I conclude the study by synthesising my findings and using research to form a new set of recommendations.

The importance of this dissertation is emphasised by two factors. Firstly, despite an increase in climate finance driven by public interest, research funding is disproportionately concentrated in East Asia and the Pacific, North America and Western Europe (Naran et al., 2022). It is crucial to note, however, that Africa is one of the most vulnerable continents to impacts of climate change while contributing the least amount of pollution and greenhouse gas emissions (Trisos et al., 2022). This imbalance has caused a research gap on climate change in the African continent, with even less research content focusing on water as a potential source of damage. Secondly, the threat of sea level rise is not accorded the necessary importance by African local and national authorities, as evidenced by the few domestic urban initiatives launched to prevent future disasters. In Sub-Saharan Africa, only 18% of climate finance is domestic, a meagre figure compared to the climate finance needs of the continent, which amount to USD 2.5 trillion (Guzmán et al., 2022). This leaves Africa susceptible and reliant on research from other continents, hindering the pioneering of domestic innovations suitable to its own unique landscape.

The aforementioned Yoruba proverb uses stagnant water as a metaphor to convey the consequences of inaction (Orímóògùnjé, 2012). Similarly, if Lagos and other African coastal cities do not take proactive measures to improve their urbanisation in response to climate change, they risk becoming stagnant societies, riddled with environmental and societal challenges. To safeguard their future and establish thriving communities, these cities must recognise the pressing need for strategic urban planning initiatives that prioritise resilience, environmental sustainability, and inclusive development.

1.2 Methodology

This study is significantly constrained by a research gap concerning urban responses to climate change in Africa, particularly in coastal areas. Initially, the research methodology focused on a comparative exploration of various African coastal zones to provide a comprehensive contextual view. However, the scarcity of scholarly papers exploring this topic, especially focused on Northern and Eastern Africa, led to a shift in research approach. Firstly, instead of examining four geographical zones, I selected a specific location- Lagos - as the primary case study. Strategically, Lagos parallels many other African coastal cities: a former British colony, it features an immense wealth gap coupled with overpopulation concerns and is currently facing the threat of sea level rise. Therefore, a microcosmic analysis of Lagos offers insights on the intersections of colonisation, urbanisation and climate change in the African continent. Additionally, a plethora of indigenous Yoruba and Nigerian scholars have authored papers regarding Lagos’ urbanisation, which has facilitated the process of gathering reliable sources for secondary quantitative and qualitative data (Chilisa, 2012).

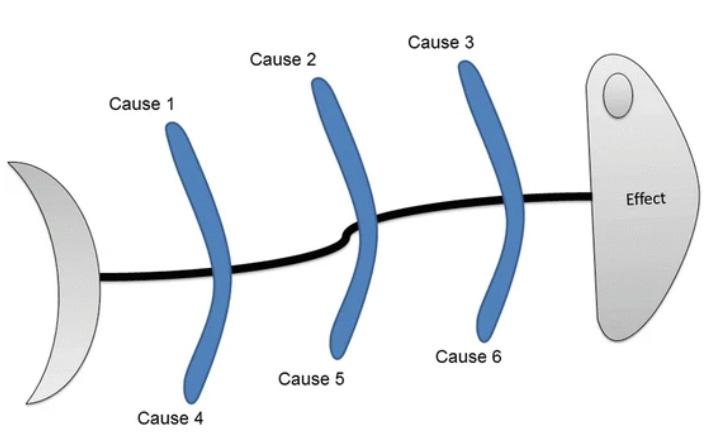

The second key aspect of the research methodology involves using a cause and effect analysis to strengthen the contextual research of my study. The method, also referred to as Ishikawa diagram, is often utilised in product design to promote quality control. Urban resilience differs significantly as a field, however, this method can be adopted into the research to effectively identify factors contributing to Lagos’ poor performance in the face of rising sea levels. Subsequently, the 5M model (Ishikawa, 1985) will be substituted, in its theoretical form, by one more adjacent to my research: Society, Economy, Policy and Environment. An early exercise attempting this can

be found in Appendix A. By categorising seemingly unrelated issues into 4 distinct factors, the research outcome in Chapter 3 can lay strong foundations for the recommendations that will be discussed in the study’s conclusions, taking into account the prevention of recurrent trends and encouraging evidence-based policy making.

Literary Review

As the study is positioned at the intersection of two seminal theories, namely post-colonialism and urban resilience, there is a vast expanse of literature encapsulating it.

Postcolonial theory

The foundational works of scholars like Homi Bhabha, Edward Said and Gayatri Spivak have significantly contributed to post-colonial theory, offering diverse perspectives on the experience of colonised entities, whether they be a person, a country or a culture. Each scholar’s concepts prove pertinent to the research topic: Spivak’s notion of the “subaltern” resonated with the ancient traditions of Lagos’ indigenous populations, suppressed by Western ideologies imposed during colonial rule. Bhabha’s concept of “hybridity” finds expression in the contemporary structure of Lagos as a city, whose urban composition still reflects the one laid out by colonialists, albeit with new elites. Said’s idea of “orientalism” parallels Western perceptions on Africa and the factors behind its many challenges. Though literature on the topic is not extensive, Ren(2020) defines postcolonial urbanism as “the analysis of power, representation, and identity transmuted for a spatial analysis of urbanisation, urban development, and urban life”. Similarly, Yeoh (2001), characterises postcolonial cities as “an important site where

claims of an identity different from the colonial past are expressed”. This sentiment is echoed in scholarly articles contesting present urban forms of African cities by exploring past cultural identities, exemplified in works such as “Traditional planning elements of pre-colonial African towns” (Ayeh, 1996).

Urban resilience

Urban resilience is a pivotal concept in contemporary urban studies, addressing the capacity of cities to endure, adapt, and transform amidst various challenges. According to Ribeiro and Gonçalves (2019), urban resilience stands on four principles: resisting, recovering, adapting and transforming. It can also be divided in five dimensions: natural, economic, social, physical and institutional. This definition has been compounded through interdisciplinary perspectives, such as engineering, environmental studies and social sciences (Kong et al., 2022). Researchers like Meerow et al. (2016) acknowledge that urban resilience is specifically pertinent within the climate change discourse, since its role revolves around coping with disturbances and change. The literature on urban resilience aids not only in recognizing missing elements in a city’s sustainability, as explored in Chapter 3 of this study, but also in identifying case studies of best practice. As Schuetze and Chelleri (2015) caution in their research, urban resilience practices have been commonly associated with gentrification and greenwashing, therefore underlining the importance of discerning genuine sustainability efforts in urban development.

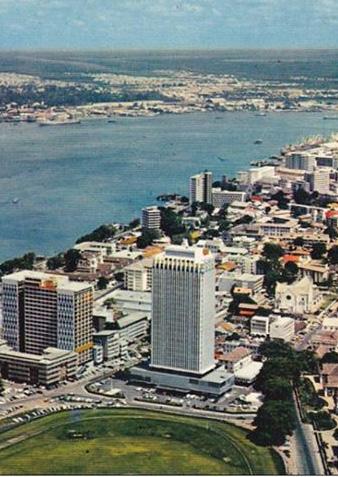

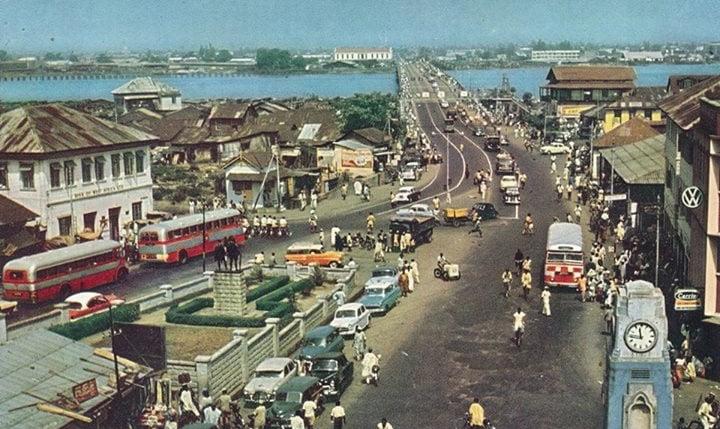

Figure 6: Aerial view of Lagos, 1960s ( Source: Delfcampe.net)

To understand the complexity of Lagos’ relationship with water, it is important to reflect on the historical underpinnings that have dictated the city’s connection with its waterscape, from its origins as a human settlement to the contemporary metropolis.

Originally referred to as Èkó, Lagos originated from a fishing village founded by the Awori, a sub-group of the Yoruba people. Though details of this historical period (pre-14th century) remain obscure (Eades, 1980), the mythological narrative at the backdrop of Lagos’ existence highlights the profound significance of water in Yoruba culture. According to oral tradition (Tijani, 2005), the Awori migrated from Ile-Ife, the cultural centre of Yorubaland, further south. This was upon instruction of an Ifa priest who set a mud plate on the Ogun River, and ordered that the Awori should settle wherever it sank. Purportedly, the plate sank near Isheri, which still exists as a neighbourhood within modern Lagos.

Figure 7: Walking distance from Ile-Ife, ancient origin of the Awori, to Isheri (Source: Google Maps)

Despite the lack of historical evidence, this account highlights a serial motif in many Yoruba myths and legends.

As opposed to Christianity and Islam, which were introduced to the land later, Yoruba cosmology recognises water as a force of its own, sometimes beneficial and sometimes destructive (Owoseni, 2017). Arguably one of the most renowned members of the Yoruba pantheon, the power and unpredictability of water is embodied by Osun and Yemoja, goddesses of riverine and sea waters . Their feminine nature reflects the nurturing and life-sustaining qualities of water, crucial for any form of life (Ajibade, 2021). Only through the worship of

water’s essence can humans harness its power towards productive activities; taboo actions like littering sacred streams, however, incur its divine wrath which manifests through flooding, tempests or drought (Owoseni, 2017).

Through these practices, pre colonial Yoruba civilizations maintained a symbiotic relationship with water, promoting the conservation of the aquatic environment.

The traditional harmony between water and humans began to erode under the influence of colonial powers, namely the Benin empire, Britain and Portugal, which conferred Lagos its name inspired by the nearby lagoon cluster . By 1850, Lagos, like many Yoruba territories, had been transformed by decades of warfare and the profound impacts of the trans-atlantic Slave Trade (Smith, 1979). The internal conflicts that ultimately weakened the greatest Yoruba empires, inversely bestowed more territorial and economic power upon Lagos. The waterways connecting Lagos to the Yoruba hinterland became vital escape routes for war refugees from neighbouring towns, contributing to the city’s population growth (Olukoju, 2019). Consequently, by the 19th century, water regressed from a sacred landscape to a transitory one - a mere channel to increase Lagos’ population influx and accelerate its transformation into a colonial city.

This conversion was exacerbated through the 1851 Reduction of Lagos. In 1833, the Slavery Abolition Act banned all slave trade activities throughout British territories, due to increasing pressure from abolitionist movements and slave rebellions. This led the British royal forces, tasked with halting slave traders, to intervene in a dispute between Oba Kosoko and Oba Akintoye, contenders for the kingship of Lagos. Oba Kosoko’s

resistance to Britain’s abolition request led to his replacement with Oba Akintoye, through what is now referred to as the Bombardment (or Reduction) of Lagos. The destruction of the city allowed British forces to superimpose a new political, commercial and subsequently, urban system. The old order did not serve the interests of the British Empire anymore, who was now more interested in exploiting Lagos for its land resources than for human capital .

From 1851 to 1861, when Lagos was annexed by the British Empire in 1861, the city witnessed a flourishing economy thanks to the export of palm oil, palm kernels, camwood and guinea grains (Olukoju, 2019). This led to the stratification of Lagos’ population into four distinct groups, causing a slow fragmentation of the city’s urban layout (Bigon, 2009). The first and most populous settlement, Isale Eko, had been established since the 16th century, and was home to the indigenous people of downtown Lagos. A second settlement emerged in the 1850s around Ehin Ogba, and became home to the Saro, emancipated slaves from Sierra Leone.This minority became known for their fluency in Latin and English, and gave birth to Africa’s first generation of lawyers, doctors and journalists (Bigon, 2009). Similarly, a third settlement in Eastern Lagos was allocated to returnees from Brazil, Cuba and Bahia, earning the designation of “Brazilian Quarters”. The artisan skills learned while in captivity allowed this community to elevate their social status and reach the middle class. The fourth quarter, sandwiched between the lagoon and the Saro settlement, was occupied by European traders and British colonial officials. This strip of land, historically used as a dumping ground by the Yoruba people, became the most desirable area of the city for European settlers (Bigon, 2009), highlighting the polarity between Western urban principles and African spatial identity.

Historically, most European capitals like London, Lisbon and Paris were strategically developed around major bodies of water; by the 19th century, these cities had established functional urban strategies that capitalised on scenic water views (Hall,1997). In contrast, pre-colonial West African city states, such as Kumasi, Ile-Ife and Timbuktu took a different approach to urbanism. As noted by Amankwah-Ayeh (1996), the centrality of these cities within their respective regions emerged as a preferred feature for indigenous rulers; being located further inland served as a defence mechanism, as well as a power dynamic to rule over tributary kingdoms and establish commerce routes. Lagos itself, before the arrival of the Portuguese, was only a vassal state with little political power.

Figure 14-19: :A comparison between the location of European capitals and the location of ancient West African centres of power (Source: Google Images/Assembled by Author)

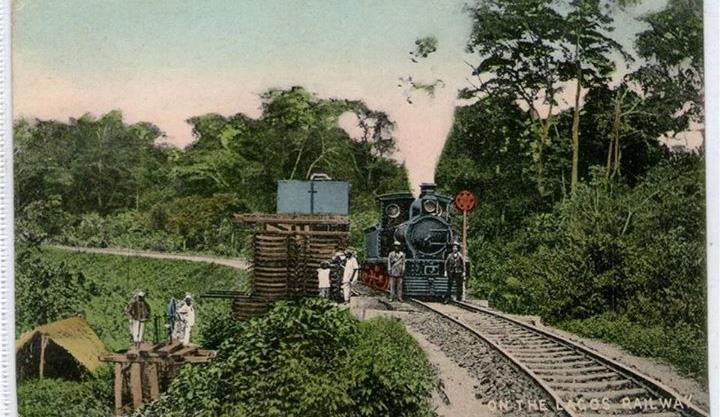

Colonialism completely overhauled West Africa’s spatial and geopolitical identity. Echoing the principles of Western urbanism, coastal settlements experienced a surge in political power and urban development, from slave trading ports to crucial hubs in the colonial economy. However, this economic prosperity did not benefit indigenous populations. The fourth Lagos quarter symbolises how urban zoning was exploited by colonial authorities to augment racial segregation in the city. Acey (2007) and Livsey (2022) note that Europeans used ideologies of hygiene, or their perceived absence in West Africans, to exclude natives from the area through discriminatory leases that prohibited subletting to non-Europeans. Furthermore, the scarce funds allocated for urban development were disproportionately funnelled into European enclaves, leaving the remainder of Lagos largely unplanned and giving rise to the earliest slums (Acey, p.58, 2007). The few infrastructural interventions in indigenous neighbourhoods- power networks, railways and transportation systems - were created solely to extract natural resources for the colonial government (Bigon, 2008). Subsequently, the inept urban system compounded by the capitalist aspirations of the British Empire, initiated the degradation of the Lagosian waterscape, resulting in the outbreak of diseases and environmental pollution (Gandy, p.368, 2004).

Figure 20: Carter Bridge street scene, 1950s (Source: Delcampe.net)

Figure 21: The Lagos Railway, 1900s (Source: Delcampe.net)

Contextual Study 3

Lagos and the Climate Crisis

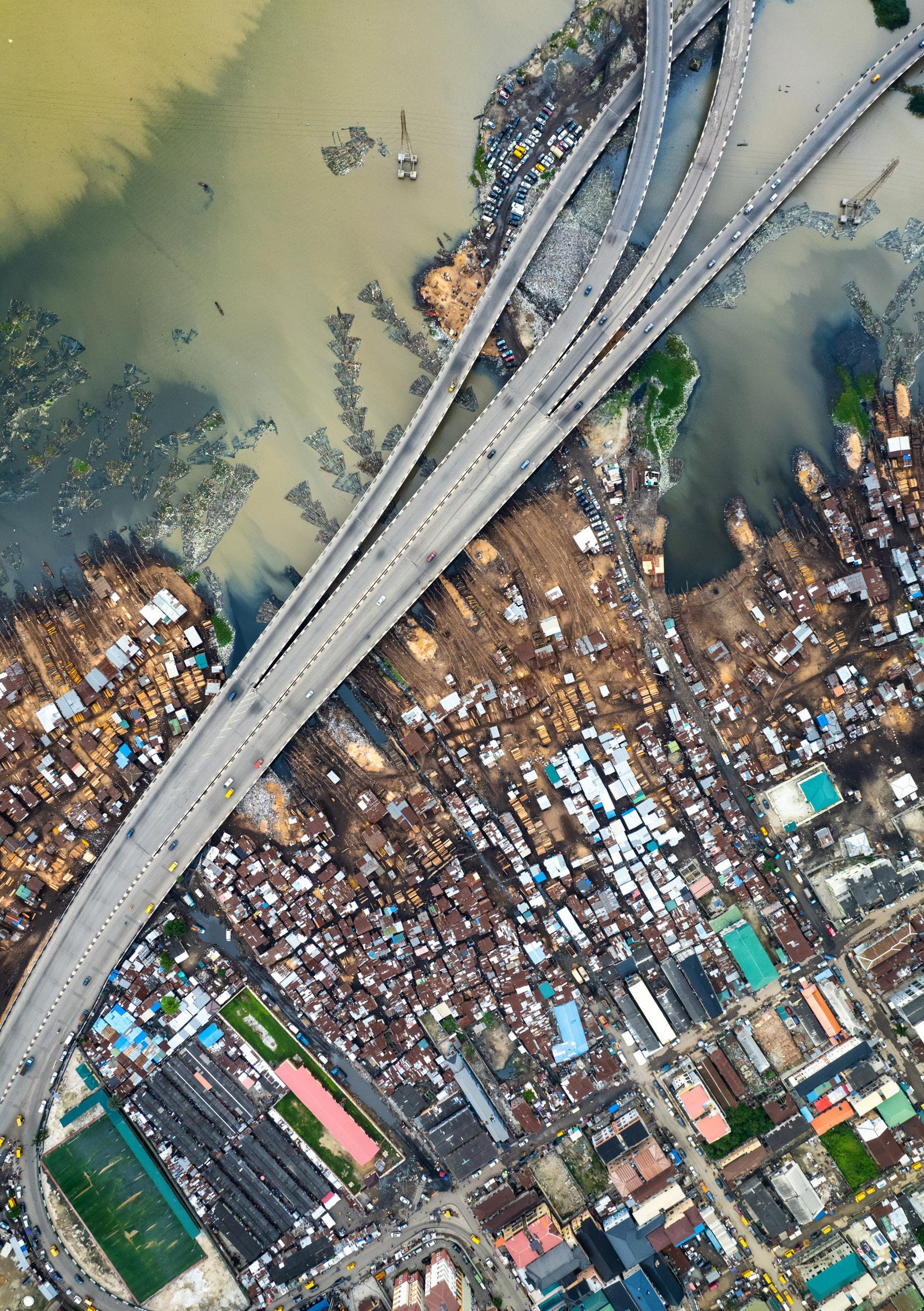

Figure 22: Makoko and the Third Mainland Bridge ( Source: Unequal Scenes)Present day Lagos, with over 12 million residents, is a crucial metropolitan area for Nigeria, contributing 30% of its annual GDP ($136.6 billion). The city’s cultural heritage and entertainment scene attracts a growing number of tourists and foreign companies. Despite glossy portrayals of Lagos exported to the global stage by Nollywood and the afrobeat music scene (Yékú, 2021), the city remains entrenched in urban inequalities rooted in its colonial past. The aforementioned European “fourth quarter” now houses the most affluent neighbourhoods in Lagos - Lekki Phase 1, Victoria Island, Ikoyi and the Lagos Marina- which, unlike the rest of the city, benefit from uninterrupted electricity, access to clean running water and relative security.

In stark contrast, just northeast of the lagoon, rise the coastal mega slums representative of Lagos’ grapple with abject poverty: Makoko, Ajegunle and Mushin (Xiao, 2021). According to a 2015 report by the World Bank, 70% of Lagos’ residents live in informal settlements, deprived of access to proper healthcare, education and employment opportunities, resulting in elevated rates of organised crime and drug addiction (LeBas, 2013). The absence of adequate sewage systems proliferates health concerns, as evidenced through a study on Ajegunle, Ijora Oloye and Makoko by Akinwale et al. (2014). The Lagos State government justifies the lack of amenities in these settlements by labelling them as informal, suggesting they should not have been erected in the first place. However, considering these slums have existed for nearly a century, this argument camouflages the fact that Lagosians have always been compelled to establish informal settlements due to shortcomings in governmental urban planning (Filani, 2013, p.13-14). Notably, Lagos’ underprivileged population continues to bear the brunt of inadequate state and federal governance. Since the 1980s, the metropolis has witnessed a growing influx of

economic migrants from rural areas and refugees from the Sahel region escaping Islamic terrorism (Uduku et al., 2021). These migrants are often absorbed into the informal fabric of the city, exacerbating the hard pressed living conditions of the poor. Furthermore, the efficacy of few infrastructural interventions across the city, notably the Lagos BRT and the Lagos Rail Mass Transit , are compromised by the infamous traffic or “go slow” caused by substandard road networks. The plight of poorer Lagosians extends to their exclusion from Lagos’ natural aquatic landscape, as most beaches in the city require entrance fees of N1000 (USD1) upwards - a significant figure for the two thirds of residents living below USD 1 per day ( Amnesty International). In a parallel reminiscent of the European Residential Areas of the 19th century, Lagos’ contemporary waterscape continues to favour Nigeria’s top elite over the average city dweller ( Titilayo, 2023).

Nonetheless, a common dilemma has now risen, transcending socioeconomic disparities. According to the 2016 IPCC Report, Lagos is among the 12 African coastal cities most susceptible to sea level rise and faces the risk of submersion by 2050 if decisive action is not taken (100RC). Initially sidelined as a climate related issue, Lagos experiences increased precipitation of 300mm and above between March and October, due to its tropical savanna climate ( Climate Change Knowledge Portal). In addition, the city’s low-rise coastline coupled with historically inept drainage systems, makes Lagos susceptible to frequent flash floods (Idowu & Home, 2017). However, the urgency of climate change gained recognition during the 2012 Nigeria floods that claimed 363 lives and internally displaced 2 million people. Based on a report of the same year by the World Health Organization, the Nigerian government sought international assistance in response to the flooding crisis, conducting multi-sector assessments in the worst affected states. A decade later, after another series of floods that resulted

in over 600 deaths, rapid urbanisation has risen as a major contributor to Lagos’ vulnerability to climate change .

Trisos et al. (2022) emphasise that preserving the natural environment is crucial for Africa’s climate resilience, with ecosystem-based adaptation mitigating risks while delivering socio-economic benefits. The continent heavily relies on ecosystem services, and as such, cost-effective measures like environmental conservation and sustainable agriculture can enhance climate resilience. A notable example of such ecosystems has historically protected Lagos’ coastline: the complex network of wetlands surrounding the metropolis slows down floodwater while promoting groundwater replenishment (Ajibola et al., 2012). However, anthropogenic activities and pressuring urban demands have endangered this ecosystem, reducing wetland coverage from 53% of total land mass in 1965 to 20% in 2017 (Idowu and Home, 2017). Practices that proliferate this phenomenon, such as land reclamation and sand filling in the lagoon, are actively promoted by the state’s governing body in pursuit of creating “Africa’s model megacity”, demonstrating a disregard for the disproportionate impact on average Lagosians compared to the top elite (Obaitor et al., 2021). Subsequently, rapid urbanisation and climate change amplify existing structural problems within Lagos’ fabric, including resource exploitation and inadequate infrastructure (Echendu , 2020).

This observation persists when evaluating climate crisis initiatives in Lagos. Two notable examples, the Eko Atlantic City and the Makoko floating school (NLÉ architects, 2013) exemplify the complex discourse on climate resilience interventions in Lagos, despite targeting different users. Eko Atlantic City, a collaboration between the state government and private investors, aims to create a premier waterfront district while addressing Lagos’ coastal erosion (Titilayo, 2023). Heralded by stakeholders as the “new Nigerian ecological city”, it is often described by urban scholars as an extreme case of climate adaptation apartheid (Acey, 2018)(Velame & da Costa, 2020). This claim is corroborated not only because it does not address the housing crisis in Lagos, being exceedingly unaffordable to the average city dweller, but also for its role behind planned displacement of slum dwellers by the state government (Ajibade, 2017). Claims of the project tackling Lagos’ coastal issues are undermined by damages from its land reclamation phase, where sand filling caused increasingly frequent flooding in the nearby area.

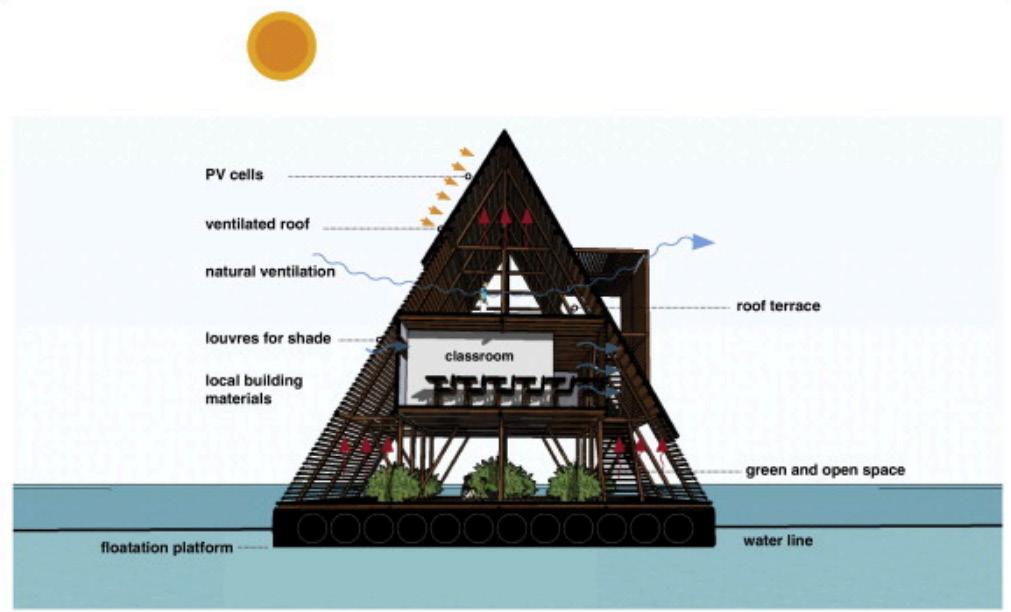

A more successful response to the need for climate resilience strategies in Lagos stood merely 12 minutes away from the construction site of Eko Atlantic City. The Makoko Floating School, serving a community of 80,000 people, was erected in 2013 by Amsterdam based practice, NLE Architects and was internationally acclaimed as a prototype of community-led urban development. The prefabricated A-frame structure, built on 250 movable plastic barrels, was designed to protect users from extreme flooding and harvest rainwater (Riise & Adeyemi, 2015). According to Roller and Hameed (2016), the project is also exemplary of how design can influence policy making, as the realisation of the school prompted the Lagos State Government to scrap plans of Makoko’s demolition. However, the school’s abandonment due to signs of instability and subsequent collapse in 2016, uncovers how the initiative unduly received its honour before standing the test of time (Maja Pearce , 2023). The project’s firm, NLE Architects, attributed structural failings on the community’s alleged neglect of maintenance responsibilities , without acknowledging the financial burden that constant maintenance would cause to the already underprivileged residents. This case study does not fall in the realm of urban apartheid like Eko Atlantic City, however, it is a stark example of “slum porn” i.e. the exploitation of poor communities by design practices for media attention and recognition (Hollmén , 2018). On the surface it may appear as a model for environmental design, yet it serves as a reminder that slums should not be treated as laboratories for architects’ experimental projects (Roller & Hameed , 2016).

Case Studies

Learning from other Cities

Various pioneering cities around the world have encountered water-related challenges akin to those currently confronting the Lagosian waterscape; hence, their adaptation methods could inform Lagos’ governing policies regarding urban innovation within the state. This section explores two case studies of best practice: China’s sponge cities and Amsterdam’s Schoonschip.

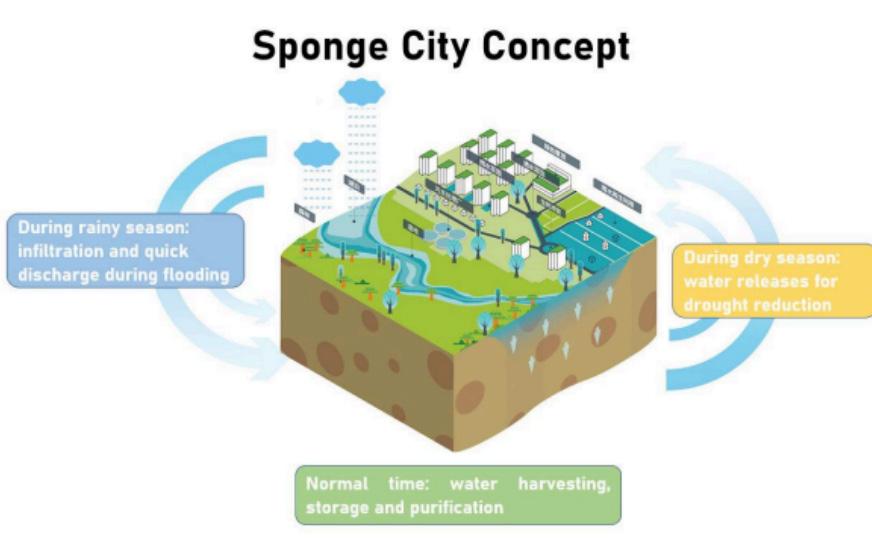

China, “Sponge Cities”

Over the past decades, many cities in China have experienced rapid urbanisation, similarly to present day Lagos. In 1980, only 19% of China’s population lived in urban areas, a figure that had rosen to 56.1% by 2015 (Liu et al., 2017). Such rapid growth resulted in a better economy, but also caused water shortages, water pollution, and flooding. Considering the recurring urban flooding incidents, the Chinese government realised the need for systems that promoted a “human–water harmony” (Zuo et al. 2016). Ultimately, in 2013 the government proposed the “sponge city” concept, a new urban development program to effectively manage rainwater. The objectives of the “sponge city” concept can be divided in three categories (Liu et al., 2017): the protection of the original ecosystems of cities (e.g. natural rivers, wetlands and woodlands), the rehabilitation of damaged natural environments in the urban area and the implementation of Low Impact Development i.e. practices that mimic natural methods of rainwater management. Despite its relatively recent implementation, sponge cities have so far achieved promising success. One such example is the Wuhan Sponge City Program; despite experiencing intense precipitation in the summer of 2020, there was a significant alleviation of waterlogging issues in Wuhan, which are typical to the city (Peng & Reilly, 2021). Other benefits observed since the implementation of the program include improved water quality, reduced urban heat island and shortened instances of flash flooding.

Figure 36: Functions of the sponge city ( Source: Polgar, 2021)

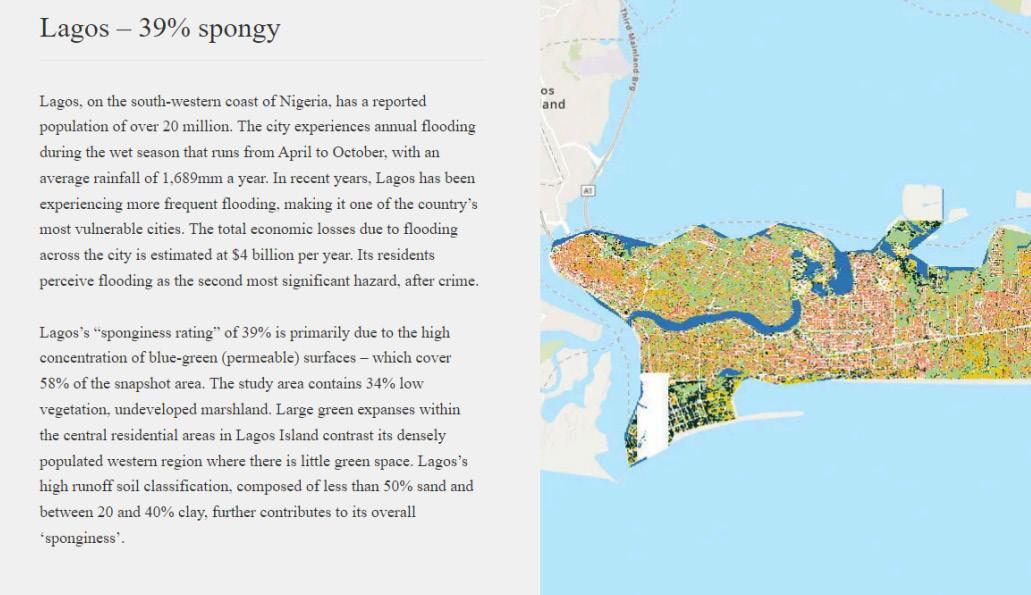

Even though the overall performance of this system is still being evaluated (Li et al., 2016), the sponge city model has already been identified by few researchers as an ideal prototype for urban climate resilience in African coastal settlements, and in the context of this study, Lagos. According to a 2022 survey conducted by Arup Group assessing the “sponginess” of African coastal cities, Lagos received a rating of 39% due to a high concentration of permeable surfaces, suggesting that adopting a “sponge city” system would be of great benefit. Corroborating this, a study by Durowoju et al (2018) concludes that integrating blue-green infrastructure in the city i.e. bioswales, artificial ponds and rainwater harvesting, could effectively manage the large volumes of yearly runoff water collected by Lagos due to its high moisture index. Nonetheless, the employment of such systems in the urban fabric of a city can give rise to governance and societal issues, particularly in Lagos, a metropolis marred by extreme economic inequality (Polgar, 2021). Arguably, the primary challenges confronting the implementation of blue-green infrastructure in Lagos centre around issues of urban injustice, inadequate project management and lack of engagement with local communities. Demonstrated by the case study of Eko Atlantic City, the introduction of sustainable development requires engagement with the local community, without displacing the urban poor and by setting timely project targets to avoid mismanagement of funds (Obebe et al., 2020). To ensure the success of the “sponge city” concept, its implementation must not be a “top-down” approach, commonly used by public bodies in China, as it could spark conflicts of interest between stakeholders which negatively impact the local community (Jiang, 2015).

Amsterdam, Schoonschip

The Netherlands, a densely populated coastal country with limited space for urban development, has historically been recognised in the field of urban design for its effective water management system. Since the 12th century, land reclamation practices resulted in the country-wide excavation of polders, which have now become synonymous with Dutch national identity. However, in recent years, the Netherlands has sought to expand the horizons of urban water management by exploring the concept of “floating cities” (Hutsler, 2017). An exemplary case study of this is situated in the industrial area of Buiksloterham, northern Amsterdam. Schoonschip, which refers to the Dutch expression “to make the ship clean”, is a sustainable floating neighbourhood comprising 46 households. This project, master planned by the Amsterdam-based practice Space&Matter, is a collective initiative led by TV producer Marjan de Block and a group of enthusiasts deeply committed to sustainable housing. With over a decade of development, Schoonschip serves as an appropriate example of community engagement in urban design: each of the 46 households, interconnected by a jetty to encourage social interactions, was designed according to the residents’ architectural choices. In addition, the research accumulated during the duration of this project is made available to the public through the community’s open source website, setting a precedent for transparency in experimental urbanism. The neighbourhood also features decentralised

and renewable energy systems, including a smart grid of solar panels that helps residents trade energy among themselves and water treatment technologies to recycle wastewater (Greenprint: Schoonschip, Amsterdam, 2021).

As observed by Ortner (2020), projects like Schoonschip are prototypical in nature, serving as models for wider application. Despite its modest scale, Schoonschip has already proven effective: it is not just a mere “umbilical cord” feeding “hungry nodes”, but achieves local loop closure through resource exchange between households. This model of communal urbanism is embedded in Lagos’ metropolitan culture, especially coastal slums like Makoko. Lawanson (2015) highlights that Lagos’ urban poor have been able to develop adaptive traits, such as pooling of resources for communal construction, which see neighbours using each other as infrastructure. Therefore, Schoonship’s urban prototype could fit seamlessly in the already self-sustaining communities of Lagos, transforming the coastal environment from a source of vulnerability into a productive landscape. Hustler (2017), in her research on sustainable integration and Dutch policy making, questions whether the concept of floating homes serves more as an opportunity to create a new social construct within the Netherlands’ elite class than to promote sustainable urbanism. This is a pertinent remark, given that each household in Schoonschip’s neighbourhood had to contribute €70,000 to cover the collective services, an unaffordable figure for the average Dutch citizen . Hence, for Schoonschip’s model of floating neighbourhood to be applicable in Lagos, a city characterised by both opulence and abject poverty, its implementation must rely on government funding and prioritise the communities most susceptible to climate change impacts.

5Conclusion

Summary of Findings and Recommendations

Figure 42: A typical street scene in Lagos ( Source: Unsplash)As stated in the introduction, the study set out to critically examine the environmental and climatic challenges facing Lagos, an African waterscape , through the lens of history, socio-economics and urbanisation. Revisiting the research methodology, the approach outlined involved an adaptation of Ishikawa’s cause and effect analysis, considering society, economy, environment and policy as principal factors.

These aspects, during the course of this study, emerged as significant actors in Lagos’ current climate vulnerability. Lagos’ societal fabric has been deeply transformed by the historical legacies left by colonialism, which continue to govern the city’s urban layout. The traditional reverence and respect for water, particular to the Yoruba indigenes of the city, has been overshadowed by the exploitation of the coastal landscape - first as a middle passage in the Transatlantic slave trade, and later on, as a playing field for colonial powers like the British Empire. The stark disparity between indigenous populations and Western settlers that arose through the imposition of European Reserved Areas in 20th century Lagos has morphed itself into contemporary urbanisation patterns that favour primarily the city’s top elite. This motif, compounded with weak governance policies on behalf of the state authority, increasingly exposes the average city dweller and the urban poor to climate change impacts, including sea level rise and flooding. Despite Lagos’ natural exposure to flash flooding and intense precipitation due to climatic and geographical factors, the severity of weather conditions is exacerbated by anthropogenic activities such as land reclamation and exploitation of the aquatic landscape. The study endeavoured to go beyond a mere analysis of Lagos’ urban problems and examined case studies of local projects aimed at promoting climate change resilience. Through a brief study of Eko Atlantic City, a high profile planned district on the shores of the city, a pattern of planned displacement by the state government was identified: to reserve more land for the project, forced slum evictions and sand-filling of the lagoon were permitted, rendering many low-income households in coastal areas homeless. The approach employed in the Makoko Floating School project was recognised as a more effective method of tackling climate vulnerability, as it targeted the underprivileged population and utilised indigenous design methods to achieve its objectives. However, the school’s collapse in 2016 exposed several shortcomings on the part of the architectural firm and the state government, which failed to equip Makoko’s community with appropriate funding to maintain the school.

In Chapter 4, two case studies of best practice were selected to inform a set of key recommendations. These case studies were chosen from vastly distant locations - East Asia and Northern Europe - to highlight that successful examples of climate resilience can be found, and therefore reenacted, globally. As observed in China’s “sponge cities”, the concept is promising in tackling urban flash floods and other issues around it, such as saltwater intrusion and overburdened drainage systems. Lagos naturally possesses geographic features that categorise it as a “spongy” city e.g. wetlands, and therefore the implementation of blue-green infrastructure would benefit the city’s population far more than ecological districts targeted primarily to privileged individuals.

As Polgar (2021) remarks in their study on “sponge city” implementation in Kampala, these systems must incorporate multifunctional uses to appeal to a wider range of users. If the most vulnerable communities in Lagos are to see the benefits of a “sponge city” urban system, it must include technologies like rainwater harvesting and urban agriculture, which transform into direct economic benefits for low-income households. Schoonschip , the case study in Amsterdam, creates parallels with the existing informal infrastructure that Lagosians have established in the face of governmental pitfalls. Similar to the way residents of the floating community exchange solar energy, many residents in Lagos engage in the daily trade of necessities. Technologies such as heat exchangers, water purifiers and solar panel grids have the potential to significantly enhance the self-sufficiency inherent in Lagos’ society; the city urgently needs to be transformed in a productive landscape with circular economy practices to address the increasing demands posed by population growth (Akinmoladun & Adejumo, 2011).

Moreover, unlike the Makoko Floating School, Schoonschip is an open-source project, fostering collaboration and continuity. Emulating this approach would allow more local initiatives in Lagos to build upon each other’s progress, promoting sustainable growth without adversely impacting the communities they aim to target.

In conclusion, Lagos emerges as an enduring city, determined to reshape its waterscape amidst profound colonial legacies and socioeconomic divides. While climate change poses a serious threat to the city, it also presents an opportunity for a future where sustainable urban design and community-centred initiatives forge a thriving and resilient metropolis.

This page has intentionally been lefty blank

References

• Acey, C. (2007). Space vs. Race: A historical exploration of spatial Injustice and unequal access to water in Lagos, Nigeria. Critical Planning, 14, 49–70.

• Adama, O. (2017). Urban imaginaries: funding mega infrastructure projects in Lagos, Nigeria. GeoJournal, 83(2), 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-016-9761-8

• Adewoyin, Y., Mokwenye, E. M., & Ugwu, N. V. (2020). Environmental ethics, religious taboos and the Osun-Osogbo grove, Nigeria. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 11(4), 516–527. https://doi.org/10.1108/jchmsd-01-2020-0019

• Ajibade, G. O. (2021). Water symbolism in Yorùbá folklore and culture. Yoruba Studies Review, 4(1).

• Ajibade, I. (2017). Can a future city enhance urban resilience and sustainability? A political ecology analysis of Eko Atlantic city, Nigeria. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 26, 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ijdrr.2017.09.029

• Ajibola, M. O., Adewale, B. A., & Ijasan, K. C. (2012). Effects of urbanisation on Lagos wetlands. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3, 310–318.

• Akinmoladun, O. I., & Adejumo, O. T. (2011). Urban agriculture in metropolitan Lagos: an inventory of potential land and water resources. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning, 4(1), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.5897/ jgrp.9000154

• Akinwale, O., Adeneye, A., Musa, A., Oyedeji, K., Sulyman, M., Oyefara, J., Adejoh, P., & Adeneye, A. (2014).

Living conditions and public health status in three urban slums of Lagos, Nigeria. South East Asia Journal of Public Health, 3(1), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.3329/seajph.v3i1.17709

• Aliu, I. R., Akoteyon, I. S., & Soladoye, O. (2021). Living on the margins: Socio-spatial characterization of residential and water deprivations in Lagos informal settlements, Nigeria. Habitat International, 107(0197-3975), 102293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102293

• Arowolo, A. L., & Lalude, O. M. (2022). “Their color is a diabolic die” colonialism and the state of environmental justice in Africa. Society & Sustainability, 4(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.38157/ss.v4i2.418

• Ayeh, K. A. (1996). Traditional planning elements of pre-colonial African towns. New Contree, 39(03799867).

• Bigon, L. (2008). Between local and colonial perceptions: the history of slum clearances in Lagos (Nigeria), 1924-1960. African and Asian Studies, 7(1), 49–76. https://doi.org/10.1163/156921008x273088

• Chilisa, B. (2012). Indigenous research methodologies. Sage Publications.

• Durowoju, O. S., Olusola, A., & Anibaba, B. W. (2018). Rainfall runoff relationship and its implications on Lagos metropolis. Ife Research Publications in Geography, 16(1), 25–33.

• Echendu , A. J. (2020). The impact of flooding on Nigeria’s sustainable development goals (SDGs). Ecosystem Health and Sustainability, 6(1).

• Filani, M. O. (2013). The changing face of Lagos: from vision to reform and transformation. Cities Alliance. https://www.citiesalliance.org/sites/default/files/Lagos-reform-report-lowres.pdf

• Gandy, M. (2004). Rethinking urban metabolism: water, space and the modern city. City, 8(3), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360481042000313509

• Greenprint. (2019). Greenprint.schoonschipamsterdam.org. https://greenprint.schoonschipamsterdam.org/

• Guzmán, S., Dobrovich, G., Balm, A., & Meattle, C. (2022). The state of climate finance in Africa: Climate finance needs of African countries . https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ Climate-Finance-Needs-of-African-Countries-1.pdf

• Hall, T. (2003). Planning Europe’s Capital Cities. Routledge.

• Hamukoma, N., Doyle, N., Calburn, S., & Davis, D. (2019). Future of African cities project discussion paper 3/2019 Lagos: is it possible to fix Africa’s largest city? https://www.thebrenthurstfoundation.org/downloads/ discussion-paper-03-2019-lagos-is-it-possible-to-fix-africa-s-largest-city-.pdf

• Hollmén , S. (2018). Interplay of cultures: 25 years of education in global sustainability and humanitarian Development at Aalto University. Aalto University.

• Hutsler, O. (2017). Floating homes: the truth of sustainable integration in Dutch policy making. The American University of Paris (France) ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

• Idowu , T. E., & Home, P. (2017). Probable effects of sea level rise and land reclamation activities on coastlines and wetlands of Lagos, Nigeria. The 2015 JKUAT Scientific Conference.

• Ishikawa, K. (1985). What is total quality control? THe Japanese way (Illustrated). Prentice Hall.

• Jeremy Seymour Eades. (1980). The Yoruba today. Cambridge University Press.

• Jiang, Y. (2015). China’s water security: current status, emerging challenges and future prospects. Environmental Science & Policy, 54, 106–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.06.006

• Kanu, I. A. (2022). African ecological spirituality. AuthorHouse.

• Kong, L., Mu, X., Hu, G., & Zhang, Z. (2022). The application of resilience theory in urban development: a literature review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(33), 49651–49671. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11356-022-20891-x

• Lall, S. V., Henderson, J. V., & Venables, A. J. (2017). Africa’s cities: opening doors to the world. The World Bank.

• Lawanson, T. (2015). Potentials of the urban poor in shaping a sustainable Lagos metropolis. Untamed Urbanisms, 126–136. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315746692-19

• LeBas, A. (2013). Violence and urban order in Nairobi, Kenya and Lagos, Nigeria. Studies in Comparative International Development, 48(3), 240–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-013-9134-y

• Liu, H., Jia, Y., & Niu, C. (2017). “Sponge city” concept helps solve China’s urban water problems. Environmental Earth Sciences, 76(14). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-017-6652-3

• Livsey, T. (2022). State, urban space, race: late colonialism and segregation at the Ikoyi reservation in Lagos, Nigeria. The Journal of African History, 63(2), 178–196. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021853722000494

• Maja Pearce , A. (2023). Nothing without water. Places Journal . https://placesjournal.org/article/lagos-nigeria-and-climate-crisis/?cn-reloaded=1

• Mega, V. P. (2016). Conscious Coastal Cities Sustainability, Blue Green Growth, and The Politics of Imagination. Cham Springer International Publishing.

• Naran, B., Connolly, J., Rosane, P., Wignarajah, D., & Wakaba, G. (2022). Global Landscape of Climate Finance: A Decade of Data 2011-2020. Climate Policy Initiative. https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/ wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Global-Landscape-of-Climate-Finance-A-Decade-of-Data.pdf

• Obaitor, O. S., Lawanson, T. O., Stellmes, M., & Lakes, T. (2021). Social capital: higher resilience in slums in the Lagos metropolis. Sustainability, 13(7), 3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073879

• Obebe, S. B., Kolo, A., & Enagi, I. S. (2020). Failure in contracts in Nigerian construction projects: causes and proffered possible solutions. International Journal of Engineering Applied Sciences and Technology, 5(2).

• Orímóògùnjé, Ọ. C. (2012). Yorùbá proverbs: An insight into the indigenous healthcare delivery system and health education. South African Journal of African Languages, 32(1), 79–83. https://doi.org/10.2989/sajal.2012.32.1.11.1134

• Ortner, F. P. (2020). Micro-infrastructures: architecture in data-driven Amsterdam. Contour Journal, 6.

• Owoseni, A. O. (2017). Water in Yoruba belief and imperative for environmental sustainability. Journal of Philosophy, Culture and Religion, 28(2422-8443), 12–20.

• Peng, Y., & Reilly, K. (2021). Using nature to reshape cities and live with water: an overview of the Chinese sponge city programme and its implementation in Wuhan. Grow Green.

• Perkins, P. E. (2013). Water and Climate Change in Africa. Routledge.

• Polgar, A. (2021). Advancing the “Sponge City” concept to address climate vulnerability of the urban poor in cities in the global south: an instrumental case study in Kampala.

• Ren, J. (2020, October 15). Postcolonial Urbanism. Oxford Bibliographies.

• Ribeiro, P. J. G., & Gonçalves, L. A. P. J. (2019). Urban resilience: a conceptual framework. Sustainable Cities and Society, 50, 101625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101625

• Riise, J., & Adeyemi, K. (2015). Case study: Makoko floating school. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 13, 58–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.02.002

• RodríguezG., Passerini, G., & Ricci, S. (2019). Coastal cities and their sustainable future (III). Wit Press.

• Roller, Z., & Hameed , Y. (2016). Rendering value from slums. Contested Cities, Congreso International Madrid 2016, 5.

• Schuetze, T., & Chelleri, L. (2015). Urban sustainability versus green-washing—fallacy and reality of urban regeneration in downtown Seoul. Sustainability, 8(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010033

• Smith, R. S. (1979). The Lagos Consulate 1851 - 1861. Univ of California Press.

• Titilayo, J. A. (2023). Enclave urbanism and infrastructure outcomes: The Eko Atlantic City and urban sustainability issues in Lagos, Nigeria. [Ph.D. Thesis]. https://tuprints.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/24195/

• Trisos, C. H., Adelekan, I. O., & Totin, E. (2022). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (S. M. Howden, P. Yanda, & R. J. Scholes, Eds.). IPCC. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGII_Chapter09.pdf

• Uduku, O., Lawanson, T., & Ogodo, O. (2021). Lagos: City scoping study. African Cities Research Consortium.

• Urama, K. C., & Ozor, N. (2010). Impacts of climate change on water resources in Africa: the role of adaptation. African Technology Policy Studies Network, 29(1), 1-29.

• Velame, F. M., & da Costa, T. A. F. (2020). Socio-spatial and ethnic-racial segregation in megacities, large cities and global cities in Africa. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Africanos, 5(9).

• Walker, B., Holling, C. S., Carpenter, S. R., & Kinzig, A. P. (2004). Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability in Social-ecological Systems. Ecology and Society, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.5751/es-00650-090205

• Watson, D., & Adams, M. (2010). Design for flooding : Architecture, landscape, and urban design for resilience to flooding and climate change (Illustrated). John Wiley & Sons.

• Wong, K. C., Woo, K. Z., & Woo, K. H. (2016). Ishikawa diagram. Quality Improvement in Behavioral Health, 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26209-3_9

• Xiao, A. H. (2021). The congested city and situated social inequality: Making sense of urban (im)mobilities in Lagos, Nigeria. Geoforum, 136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.04.012

• Yékú, J. (2021). In praise of ostentation: Social class in Lagos and the aesthetics of Nollywood’s Ówàmbe genres. African Studies, 80(80), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020184.2021.2000366

• Yeoh, B. S. A. (2001). Postcolonial cities. Progress in Human Geography, 25(3), 456–468. https://doi. org/10.1191/030913201680191781

• Zuo, Q., Liu, H., Ma, J., & Jin, R. (2015). China calls for human-water harmony. Water Policy, 18(2), wp2015102.

https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2015.102

Appendix A - Preliminary Study