EMMA PODIETZ Landscape Architecture Portfolio

emmapodietz@gmail.com

ecological landscape designer

I am a landscape designer with a strong focus on ecological restoration and nature-based design. I have worked for nearly two years in the field of ecological restoration and am trained in landscape architecture, interdisciplinary research, GIS mapping and analysis, and community engagement. I strive to approach design work in a way that creatively integrates science, centers stewardship, and builds ecological resilience.

EMPLOYMENT

Restoration Production Associate; September 2021 – present

Environmental Quality Resources LLC, MD

Directed ecological restoration field crews in large-scale planting and invasive species management projects, wrote and researched management plans, conducted site assessments and surveys. Built and maintained a GIS-based system for project guidance, field data collection, and post-implementation assessment. Used GIS analysis to locate and prioritize new restoration projects.

Program Consultant; Summer 2021

Wright-Ingraham Institute, Brooklyn, NY (remote)

Developing Field Stations, an interdisciplinary workshop focused on deepening understanding of social-ecological systems. Creating curriculum on graphic landscape interpretation techniques for non-designers.

Curriculum Developer; Summer 2020

University of Maryland, College Park, MD

Developed syllabus and lectures for a graduate-level course entitled “Ecological Design & Restoration.” Integrated concepts in restoration ecology, landscape ecology, and community ecology with contemporary ecological design ideas.

Graduate Teaching Assistant, August 2018 – May 2021

University of Maryland, College Park, MD

Taught discussion sections, created and delivered technical lectures, provided design assistance, assisted in lesson planning. Assisted 6 instructors over 3 years.

GIS & Watershed Management Intern; Summer 2019

CityScape Engineering LLC, Baltimore, MD

Performed large-scale suitability analysis and detailed mapping of Baltimore properties as part of a National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) grant-funded watershed restoration project.

RESEARCH

Master’s Thesis; 2020-2021

Integrating Vegetation Dynamics Theory into the Long-Term Ecological Design & Management of Urban Public Parks: Long Branch Stream Valley, Maryland. Presented & published Spring 2021.

Baltimore Biodiversity Toolkit; 2019-2020

Conceptual Modeling at the Interface of Science and Design: The Baltimore Biodiversity Toolkit Poster Series. Research collaboration with ecologists, UMD faculty, and plant science students. Refereed posters presented at 3 conferences in 2019 and 2020.

EDUCATION

2021 - Master of Landscape Architecture, University of Maryland

2018 - GIS Certificate, Temple University, PA

2012 - B.A. Individualized Study, New York University, NY

SKILLS & QUALIFICATIONS

Maryland Forest Conservation Professional

Certified pesticide applicator - MD, VA, PA

Languages: English, Spanish

Software: ArcGIS (ArcMap), Adobe Creative Suite, SketchUp, AutoCAD, Microsoft Office, TR-55 Hydrological Modeling

Creative: Hand drawing, illustration, sewing, woodworking

AWARDS & FELLOWSHIPS

2021 MD ASLA Student Honor Award

2019-2020 MD ASLA Graduate Fellowship

2019 Wright-Ingraham Institute Fellowship

2018-2019 UMD Dean’s Scholarship

215-518-7219

EMMA PODIETZ

Long Branch Stream Valley............................................................. 4 Master’s Thesis Project Reading the Landscape..................................................................... 14 Wright-Ingraham Institute Fellowship Project Baltimore Biodiversity Toolkit Poster Series..........................28 Maryland ASLA Fellowship Project; Collaborative Research Urban Design Studio Project Route 40 Ecological Park............................................................... 18

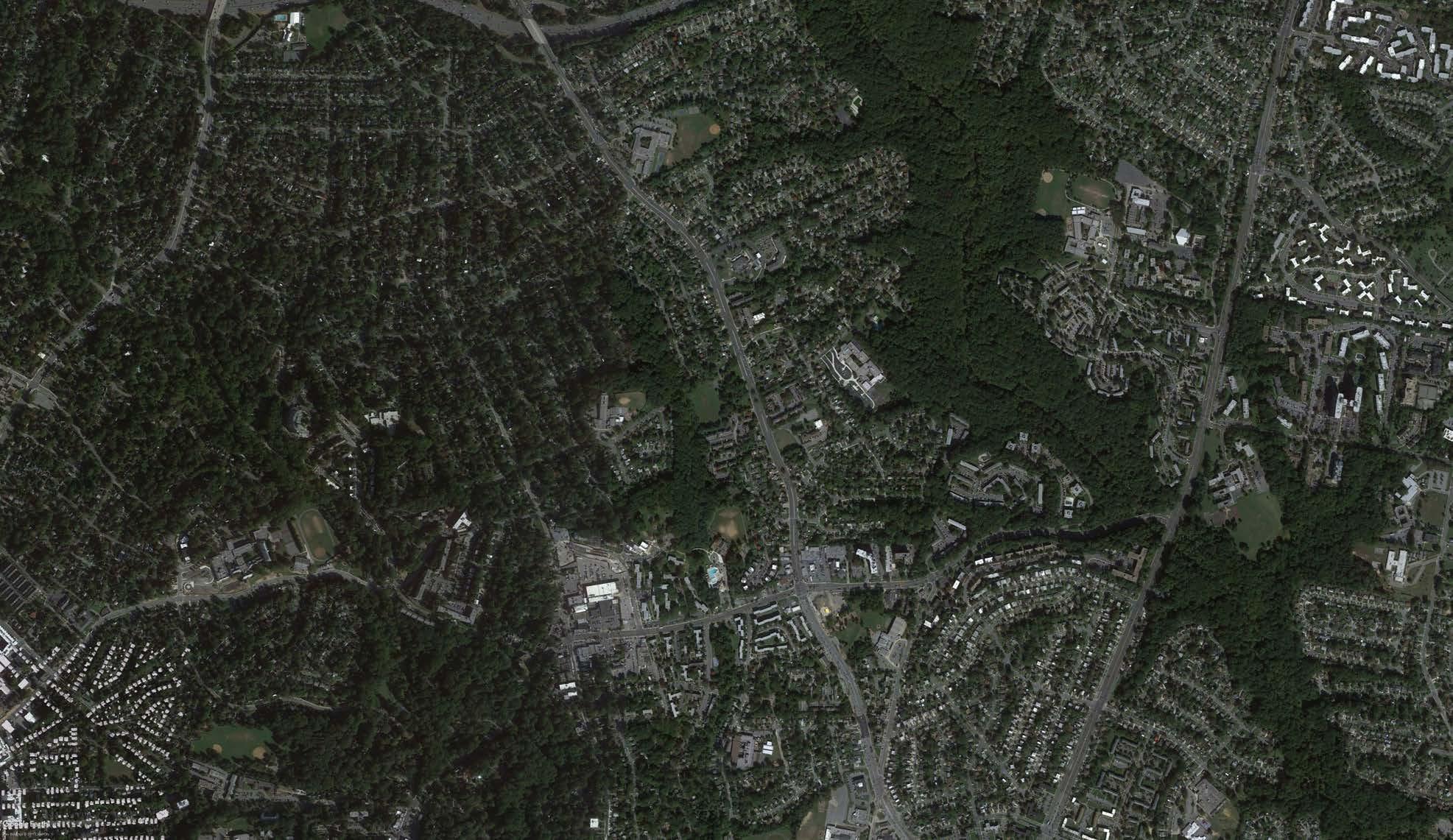

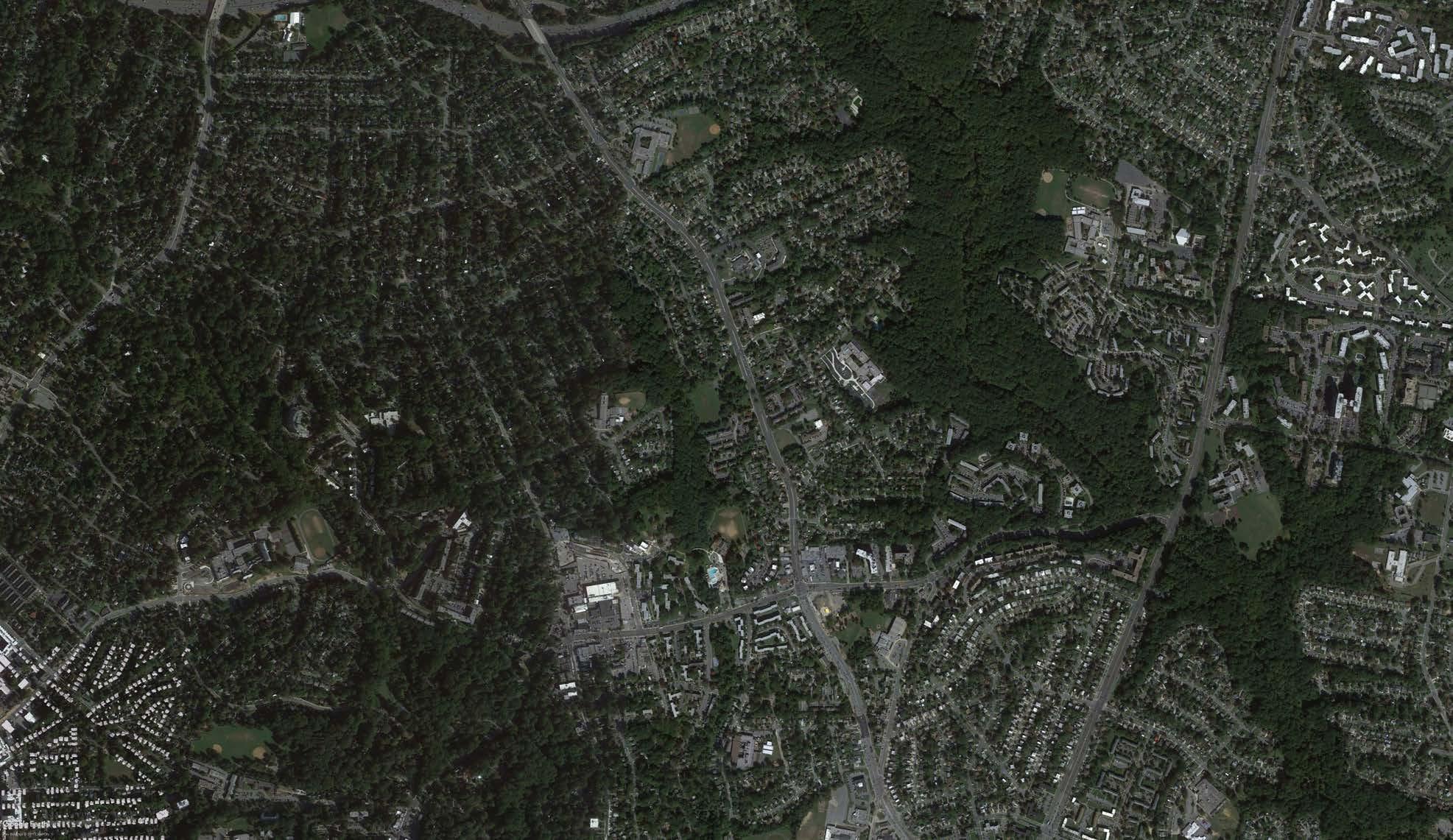

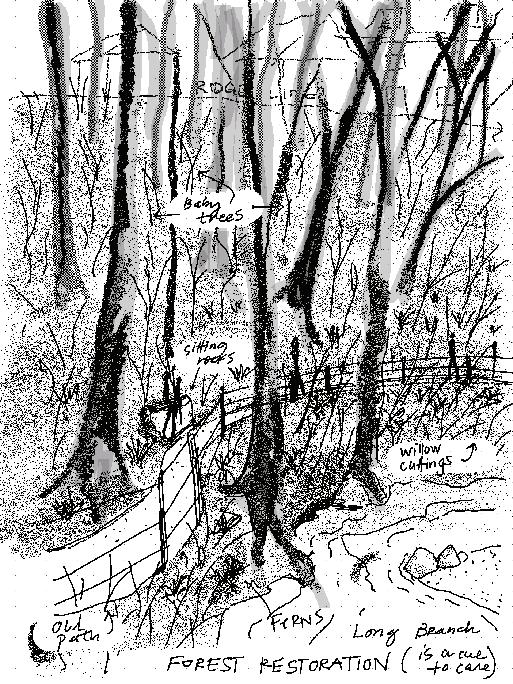

LONG BRANCH STREAM VALLEY

PROJECT TYPE:

LOCATION:

TOOLS:

Master’s Thesis Project

Long Branch Stream Valley, Montgomery County, MD

ArcGIS, AutoCAD, Illustrator, Photoshop, InDesign, SketchUp

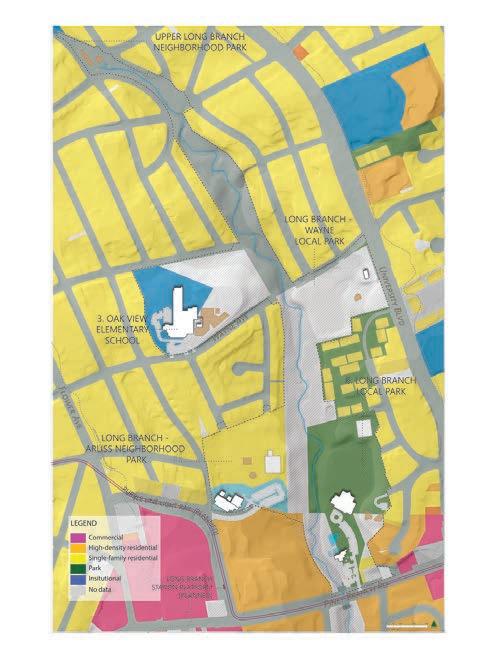

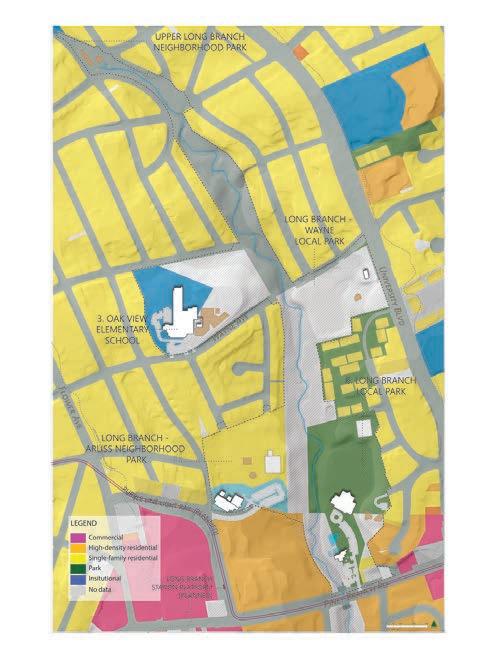

SOILS & HYDROLOGY

ZONING

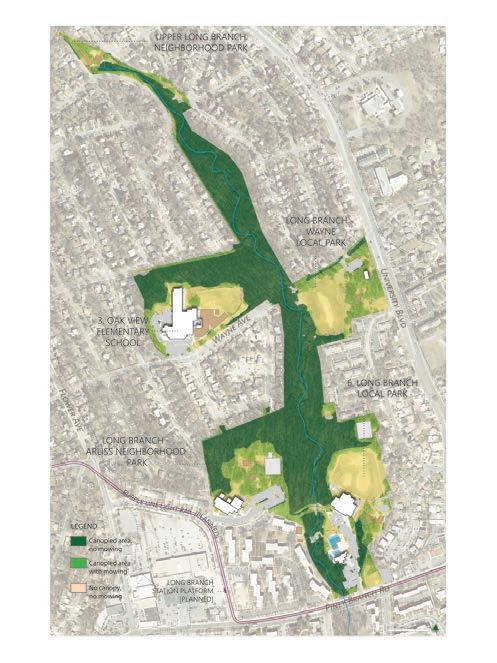

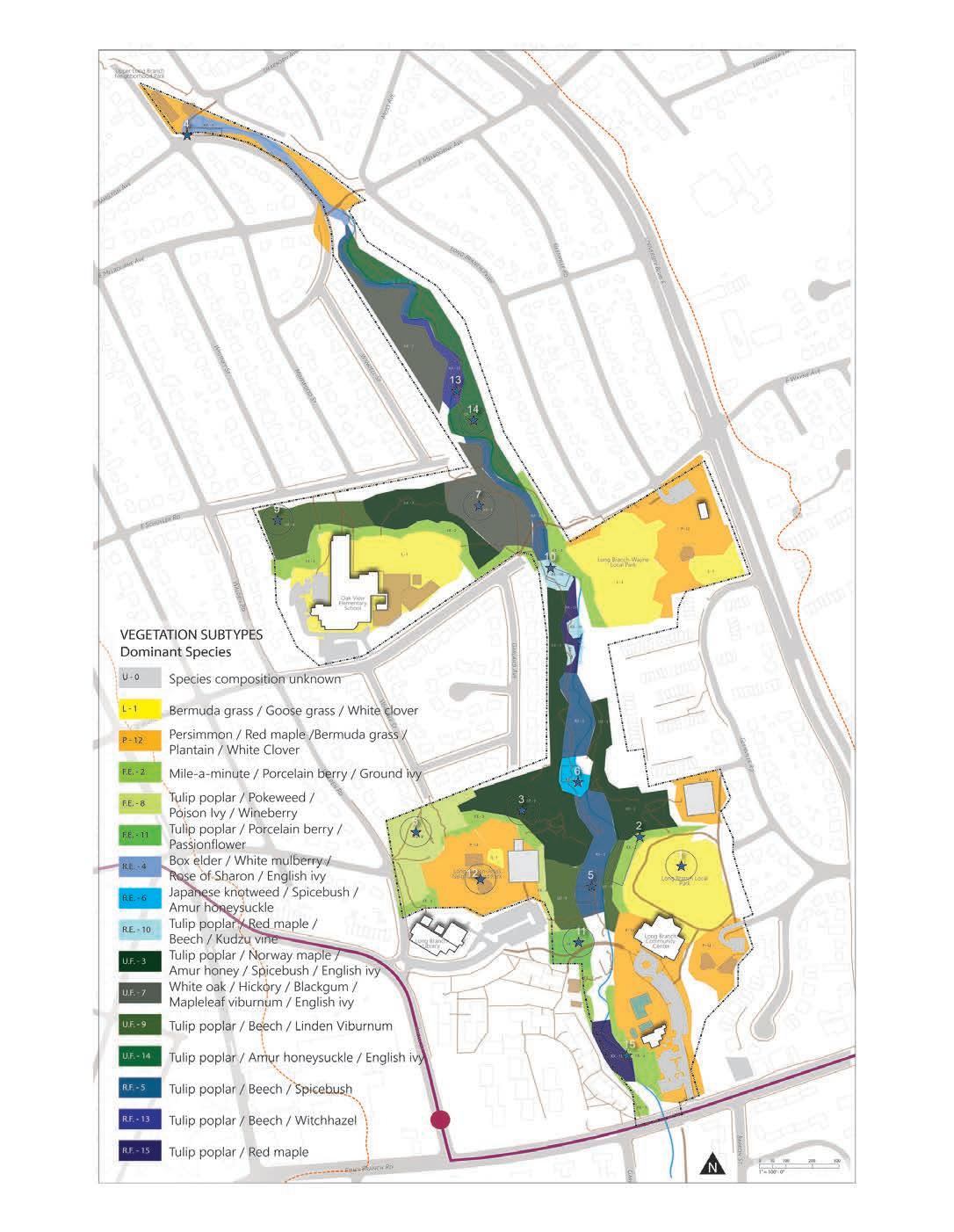

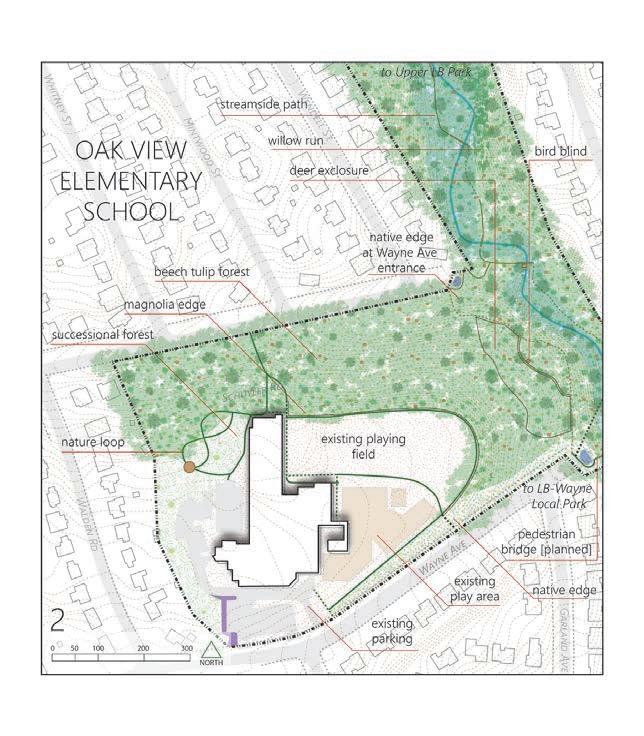

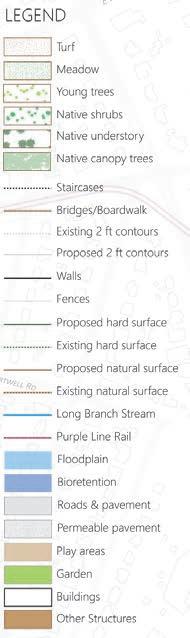

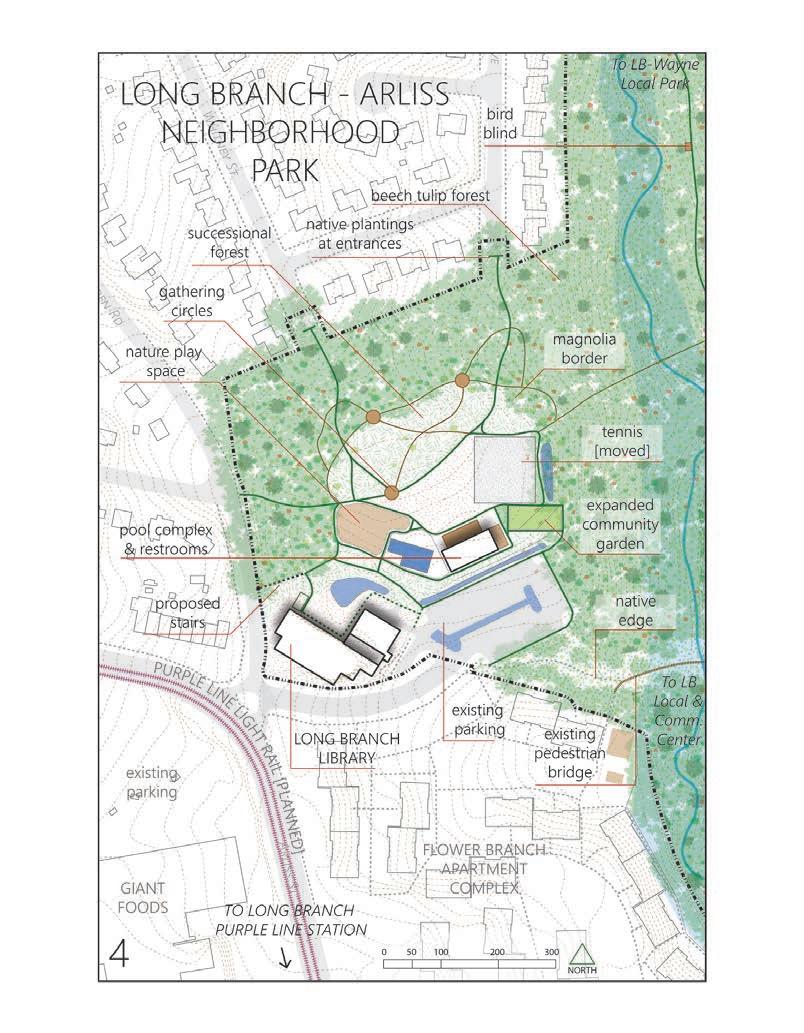

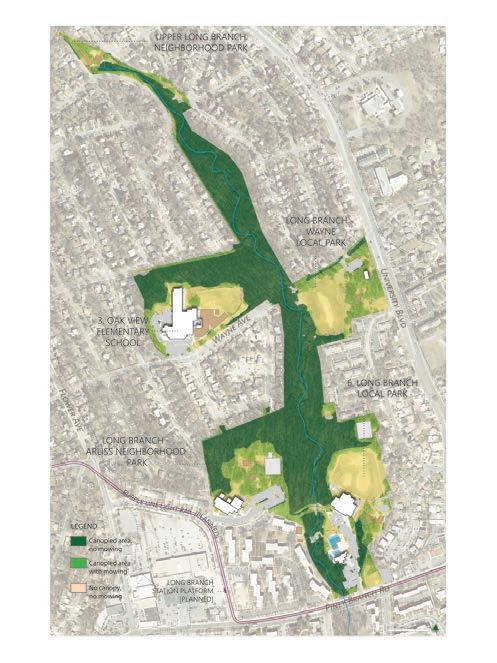

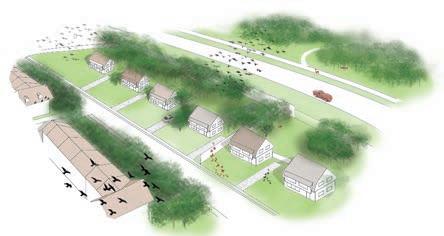

This project applies ecological succession theory to the redesign and future management of Upper Long Branch Stream Valley Parks. Through a systematic vegetation inventory and extensive mapping efforts, the project envisions how Long Branch can rebuild its ecological integrity while accommodating projected future uses and meeting community needs.

DESCRIPTION:

FIELDWORK & VEGETATION

UniversityBlvd E Flower Ave Piney Branch Rd LongB r cna h 300’ N

MARYLAND

4

TRANSIT & CIRCULATION

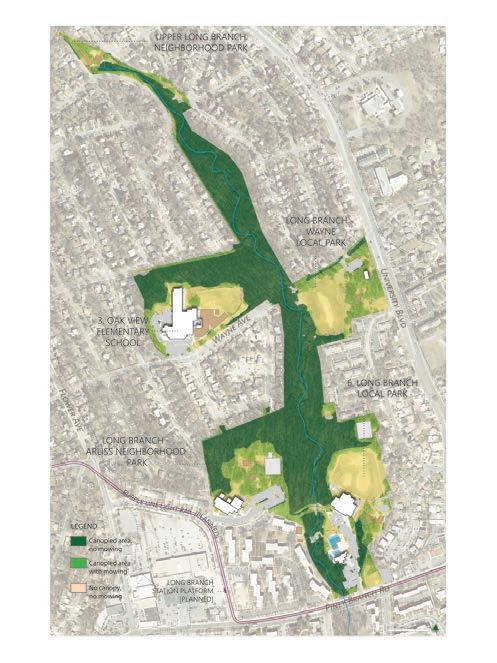

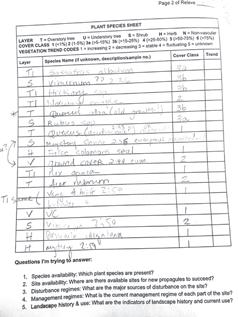

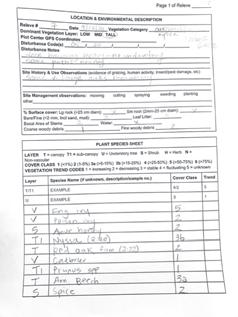

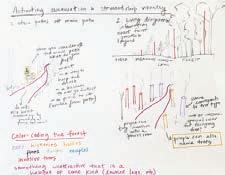

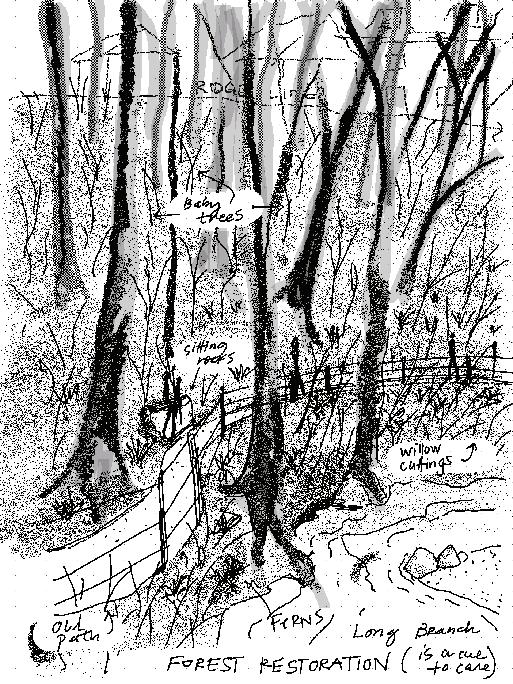

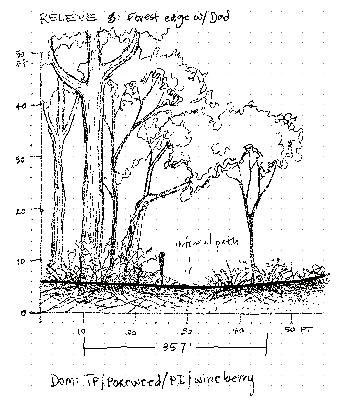

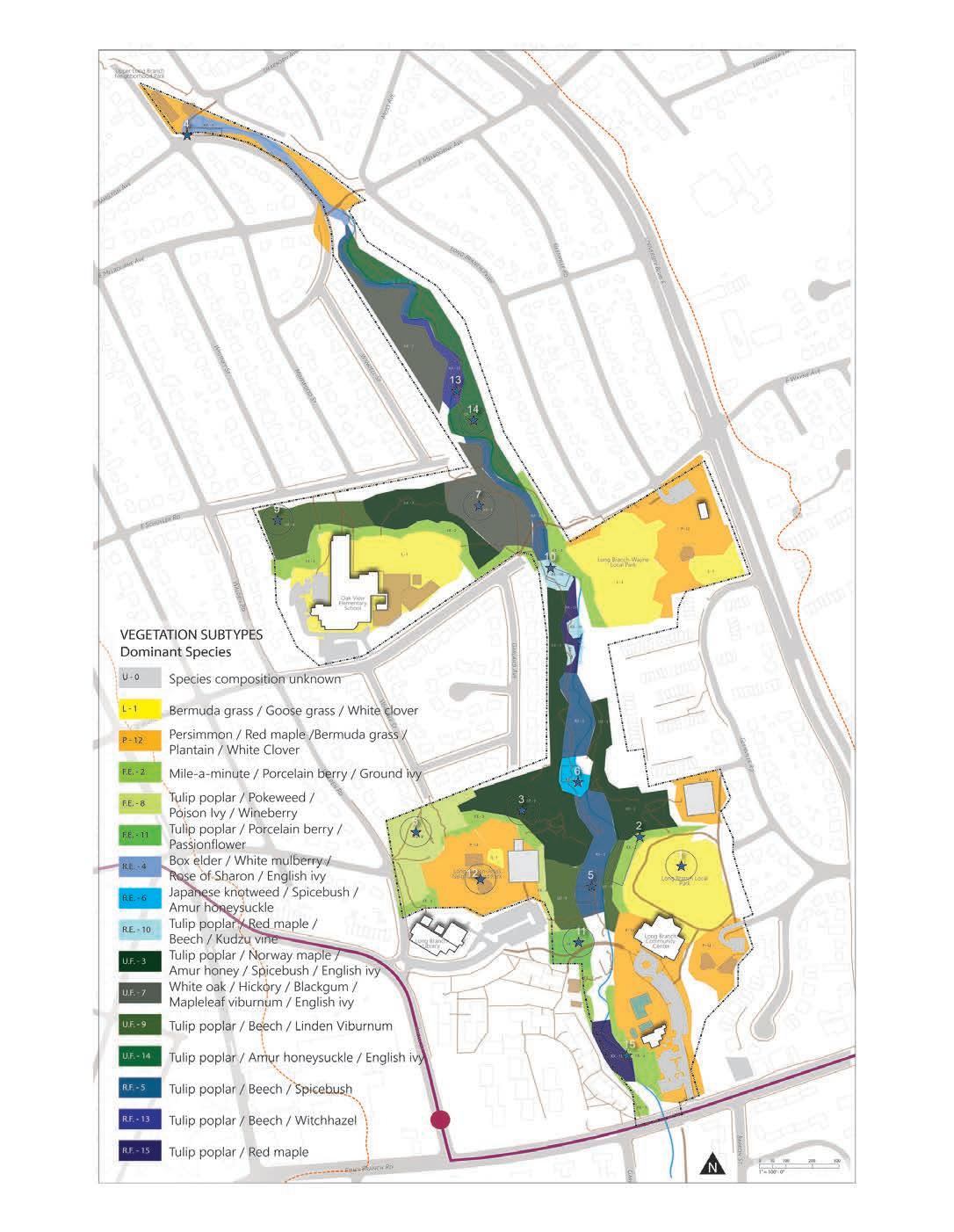

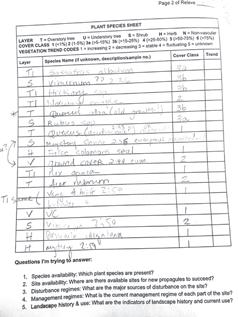

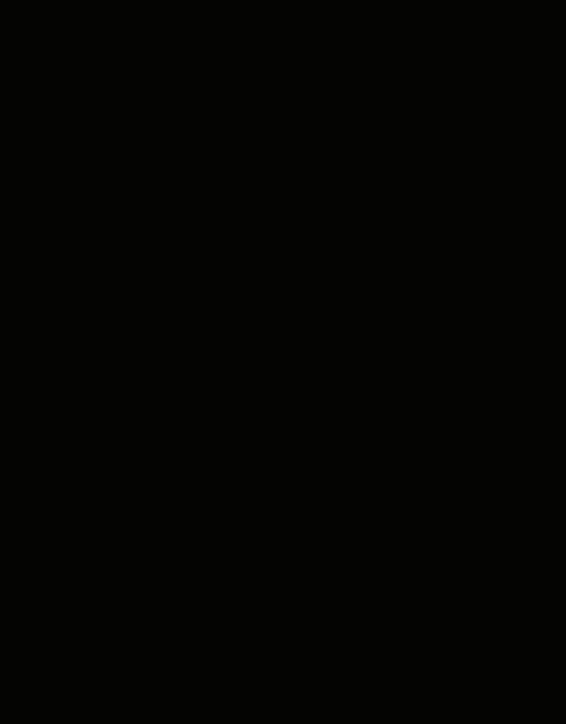

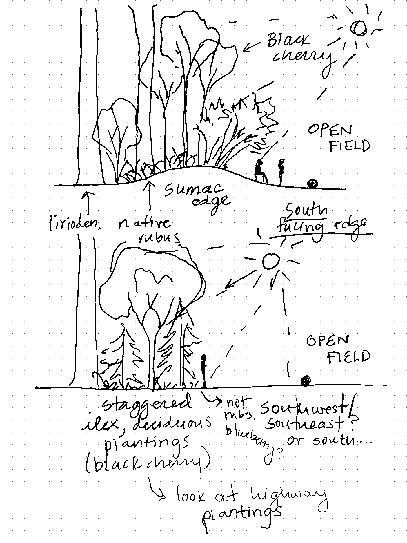

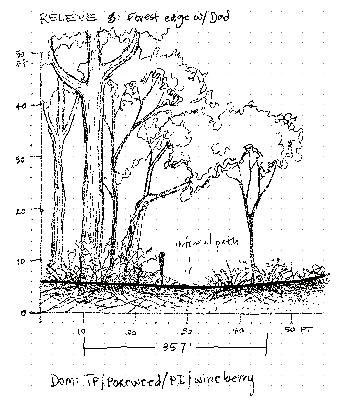

I completed a systematic vegetation inventory using a rapid assessment (relevé) method. After walking the site extensively, I selected 15 sample plots that reflected the structural and compositional diversity of the vegetation.

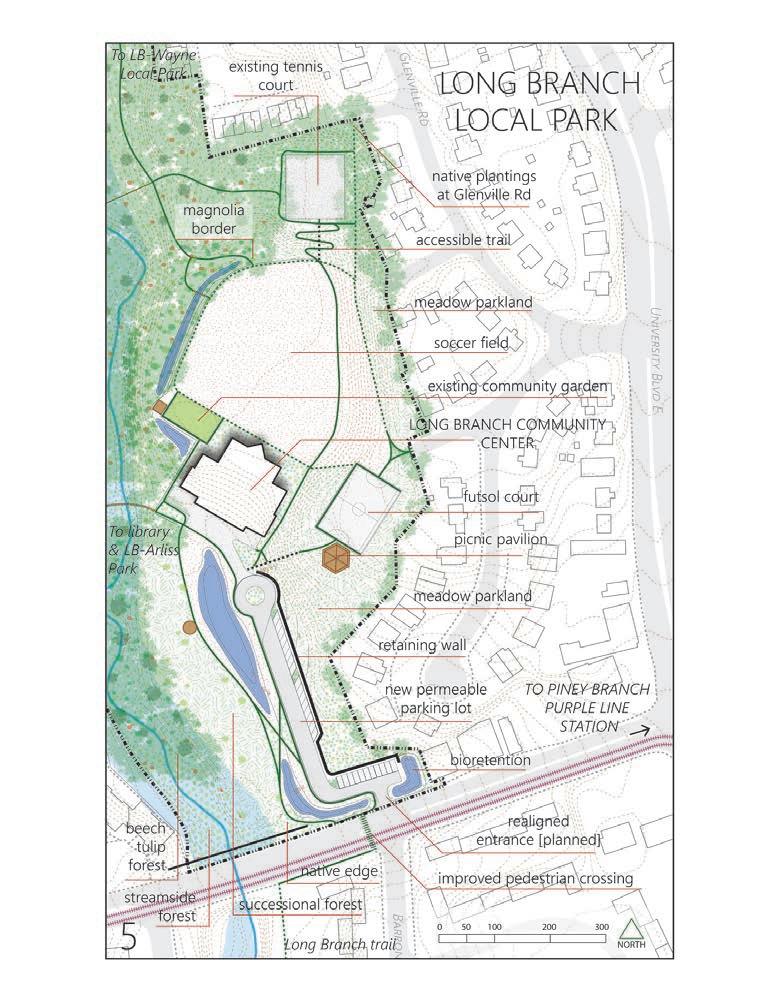

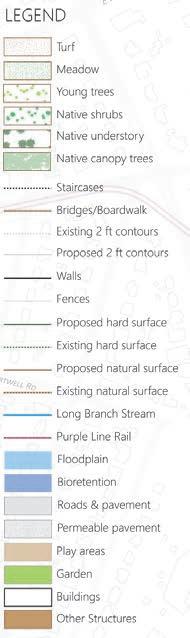

LEGEND

Relevé Plots

This map shows where each of the 15 vegetation associations appeared at the time of inventory, according to my observations. This detailed snapshot of the site’s plant community was intended to help inform its ecological status and future potential.

Data sheet examples

ArcGIS, Adobe Illustrator

ArcGIS, Adobe Illustrator

VEGETATION INVENTORY

FOREST COVER

5

MAPPING VEGETATION BY DOMINANT SPECIES ASSOCIATIONS

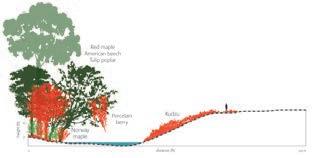

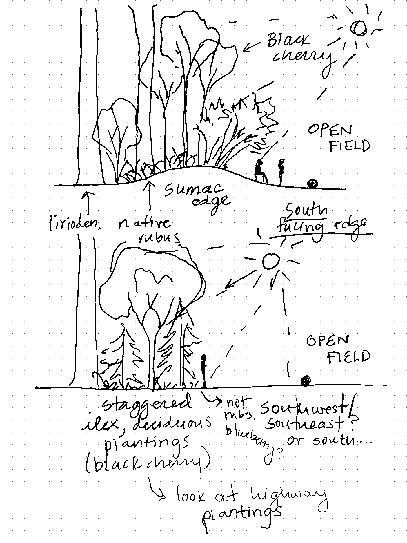

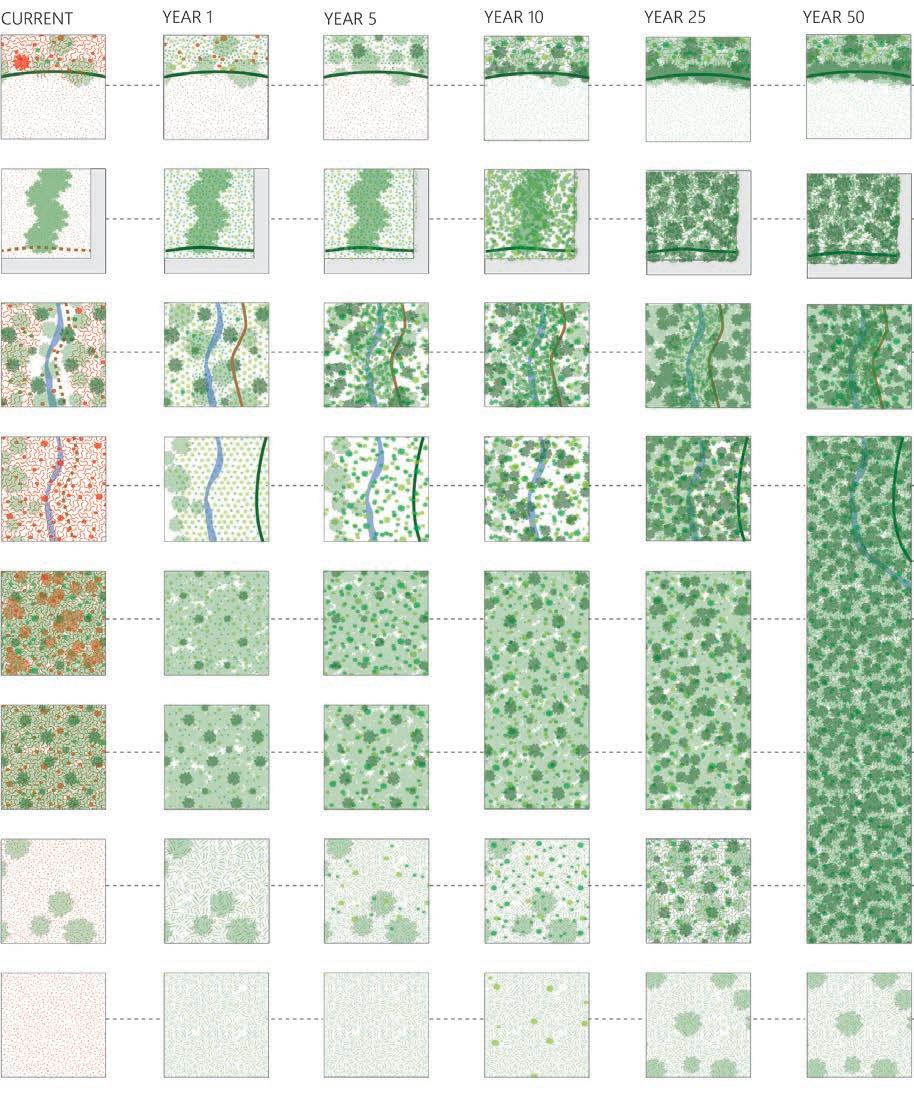

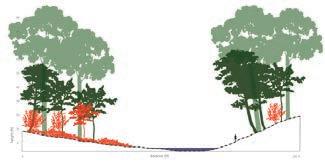

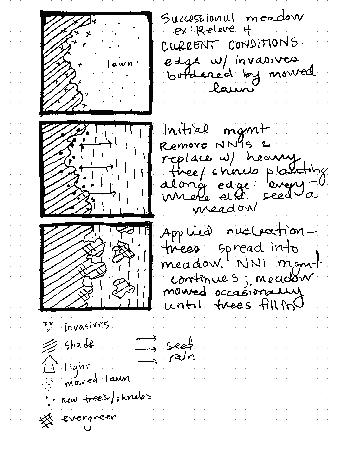

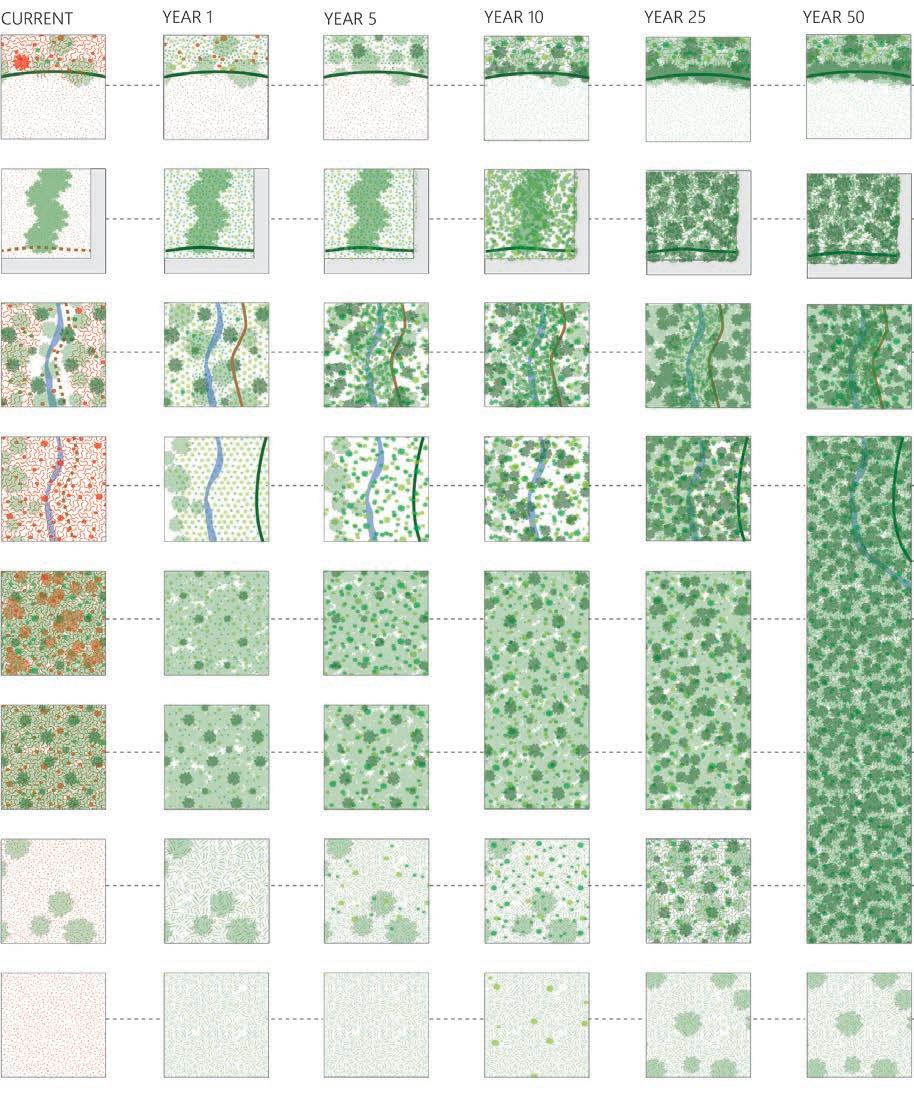

DATA ANALYSIS & IDEATION VEGETATION CHANGE OVER TYPOLOGIES FOR LONG BRANCH

To assess the site’s vegetation conditions and set goals for ecological restoration, I analyzed some aspects of the structural and compositional quality of the existing forest and parkland.

INTERSTITIAL EDGE SCOURED BANK

FIELD-FOREST EDGE

The data I collected informed my reflection on the vegetation dynamics present on the site, and how they could potentially be changed to improve the ecological and aesthetic quality of Long Branch.

FULLY INVADED FOREST

SPECIES ORIGIN ACROSS ENTIRE SITE

NUMBER OF SPECIES BY GROWTH FORM & ORIGIN

LESS INVADED FOREST

NONNATIVE INVASIVE

NATIVE

PASTORAL PARKLAND

VISIBILITY CORRIDOR

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 Tulip poplar English ivy Amur honeysuckle Northern spicebush American beech Red maple Norway maple Poison ivy Wintercreeper Porcelain berry Ground ivy White muberry Pokeweed Bermuda grass Nonnative cherry Virginia creeper Multiflora rose Legend Native Non-native Species Sum of cover class values from all plots MOST ABUNDANT SPECIES ACROSS ALL PLOTS Legend Native Could not be determined Non-native 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 Number of species observed Growth form & origin

Tree Shrub Woody vine Herbaceous vine Grass Forb/Herb

52%

38% CBD 7%

3%

NONNATIVE NON-INVASIVE

SUNNY VINELAND

6

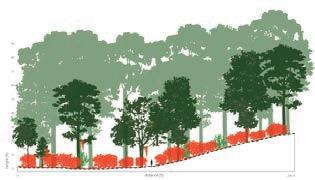

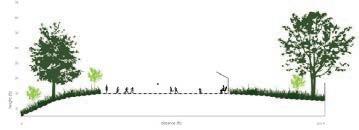

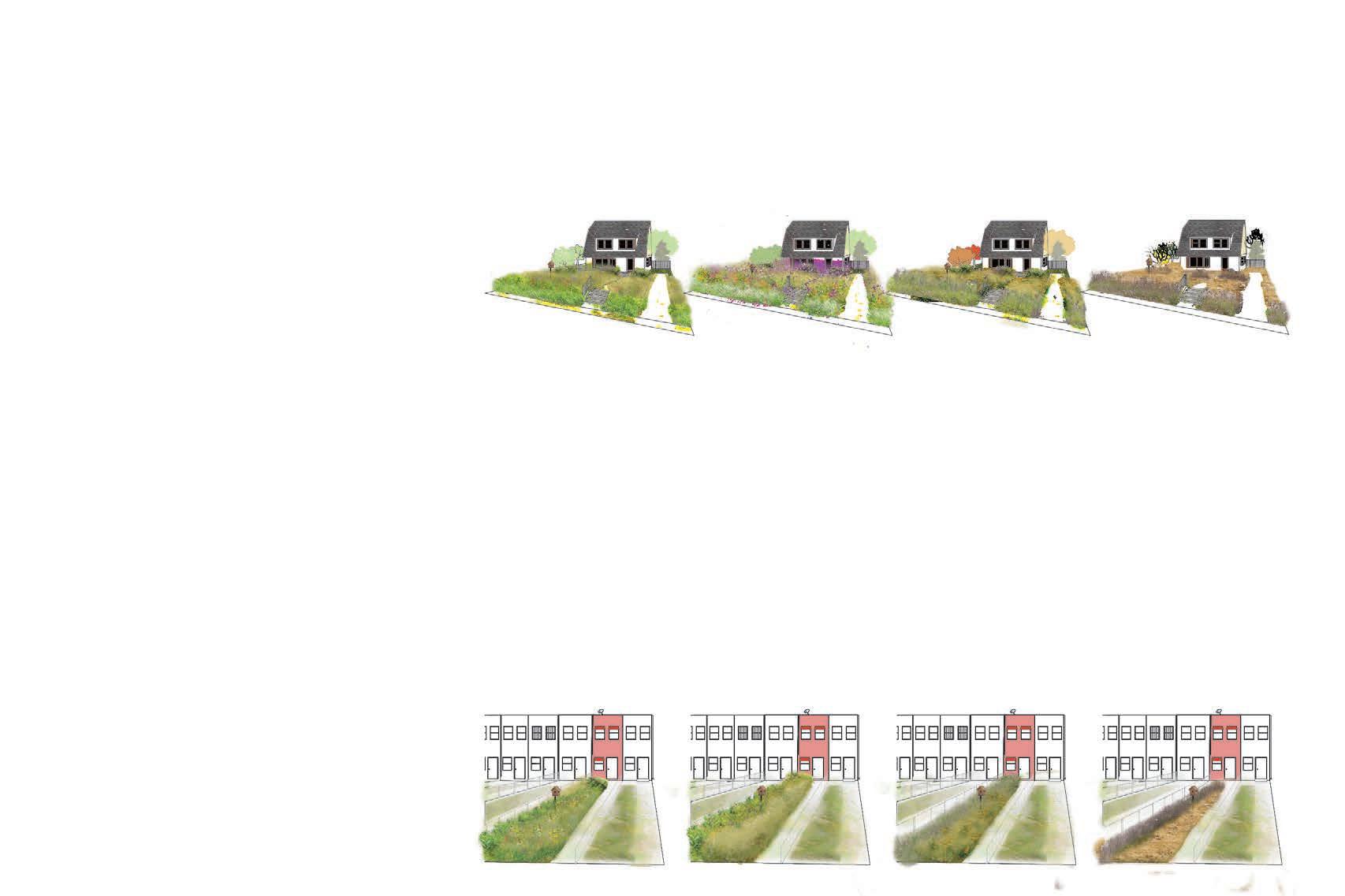

TIME: PLANTING DESIGN BRANCH

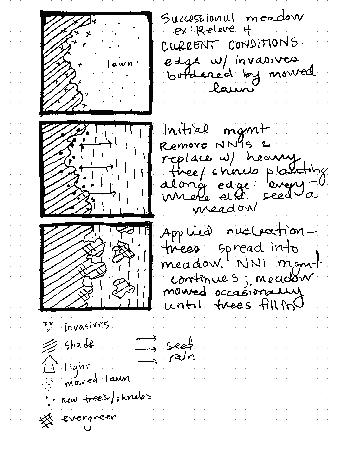

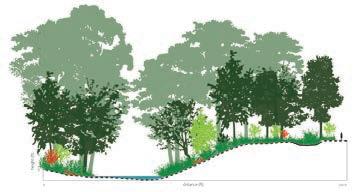

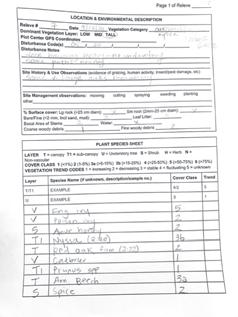

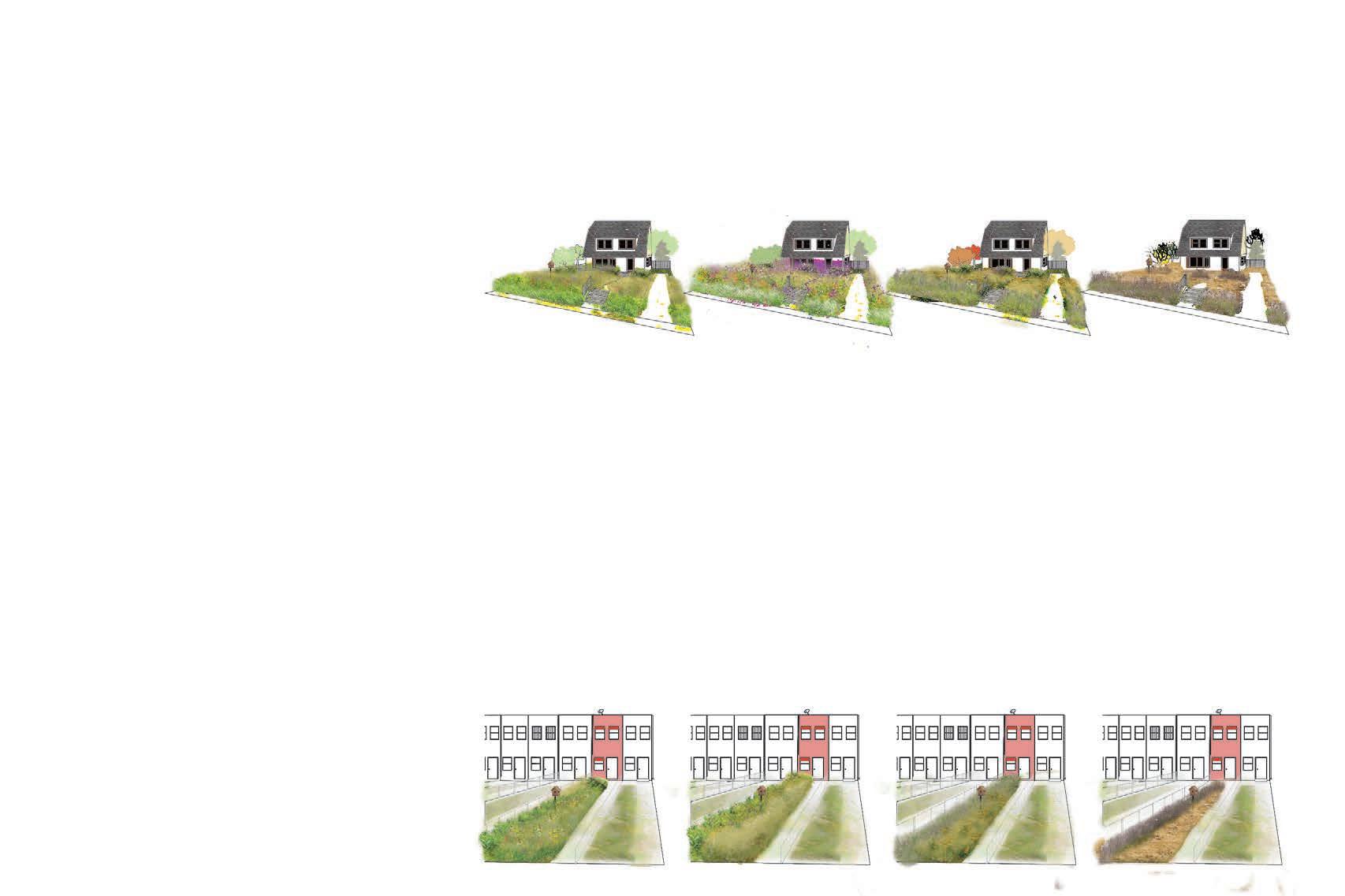

This diagram visualizes how common vegetation typologies on the site could be managed over time, eventually transitioning to more ecologically functional and aesthetically pleasing conditions.

Evergreen magnolias shade the forest interior while providing visual interest and native tree benefits.

STREAMSIDE FOREST

Densely planted interstitial spaces provide bursts of color and wildlife habitat.

Willows and other fastgrowing riparian species shade and anchor the stream bank.

Intensive multi-layered planting in riparian zones provides richness and habitat in the forest.

BEECH-TULIP FOREST

The target species for the forest restoration is based on a forest association native to Maryland.

SUCCESSIONAL FOREST

Some areas are first planted as meadows and transitioned to forests by managed succession.

Areas where visibility is necessary are maintained as meadows interspersed with large shade trees.

EDGE FUTURE

WILLOW RUN

ArcGIS,

Adobe Illustrator MAGNOLIA

TYPOLOGIES NATIVE EDGE

MEADOW PARKLAND

7

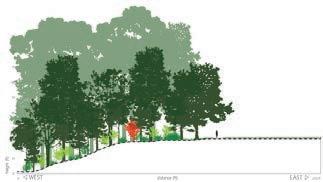

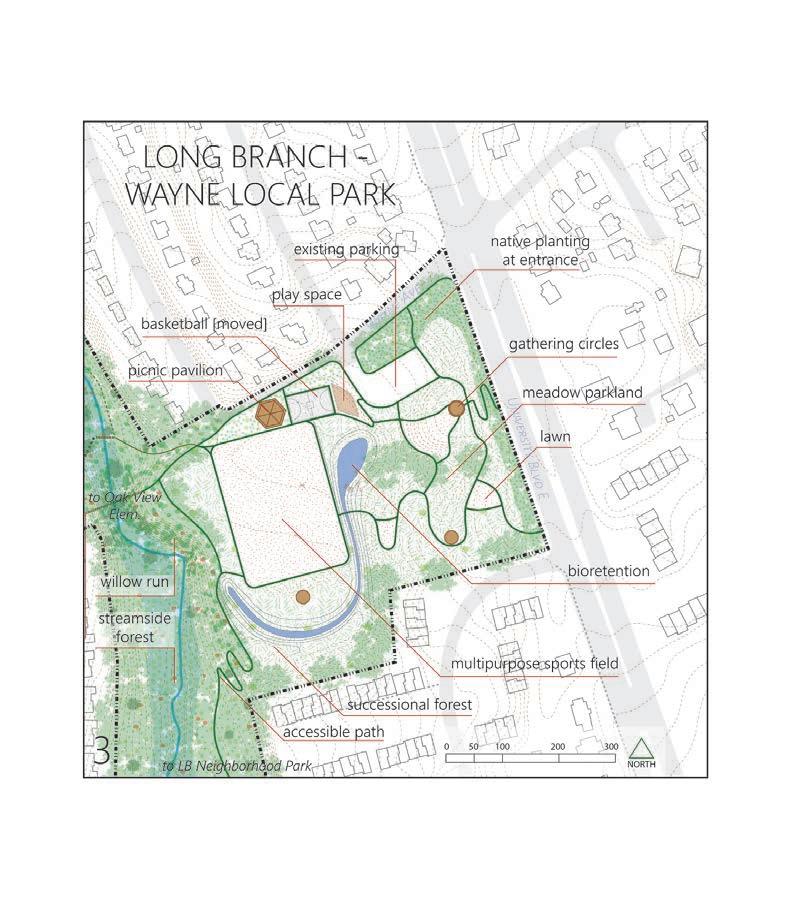

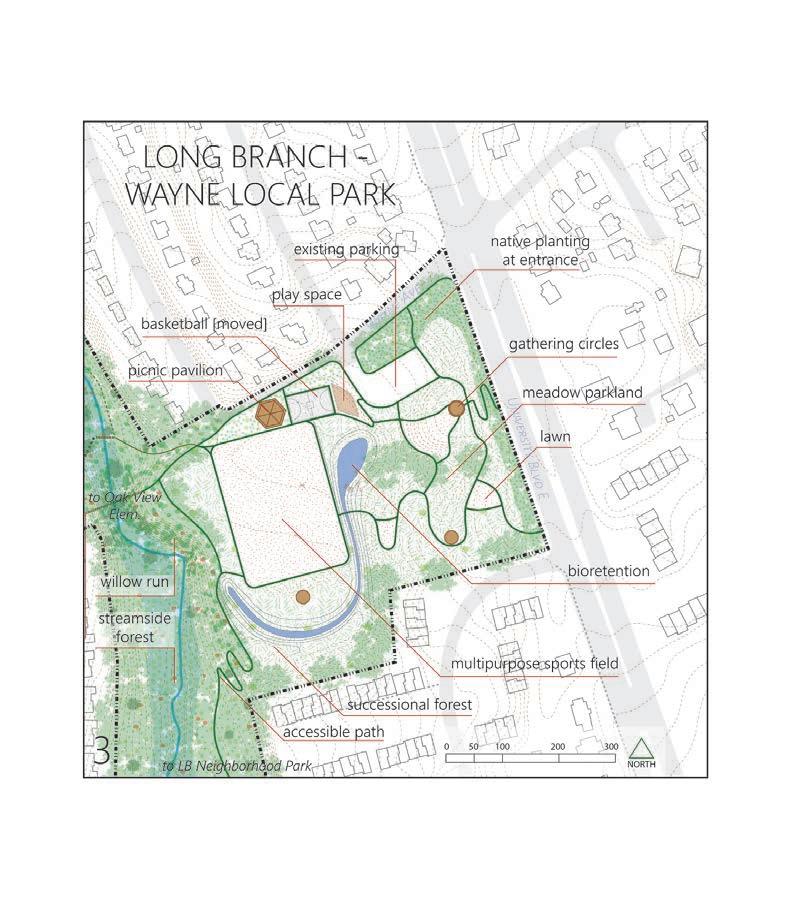

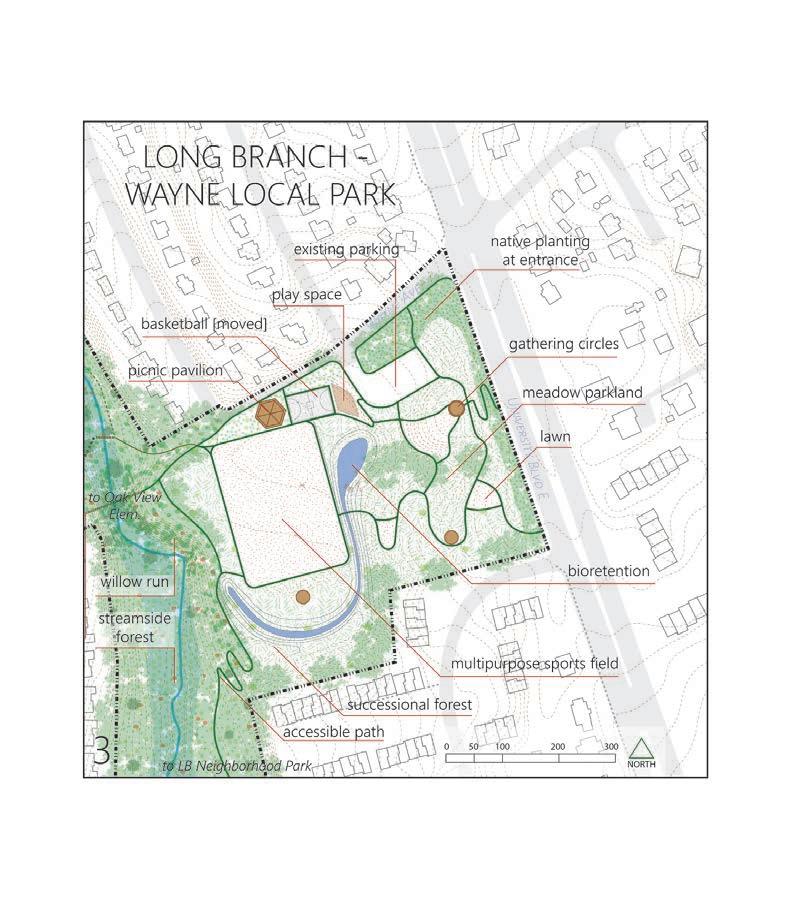

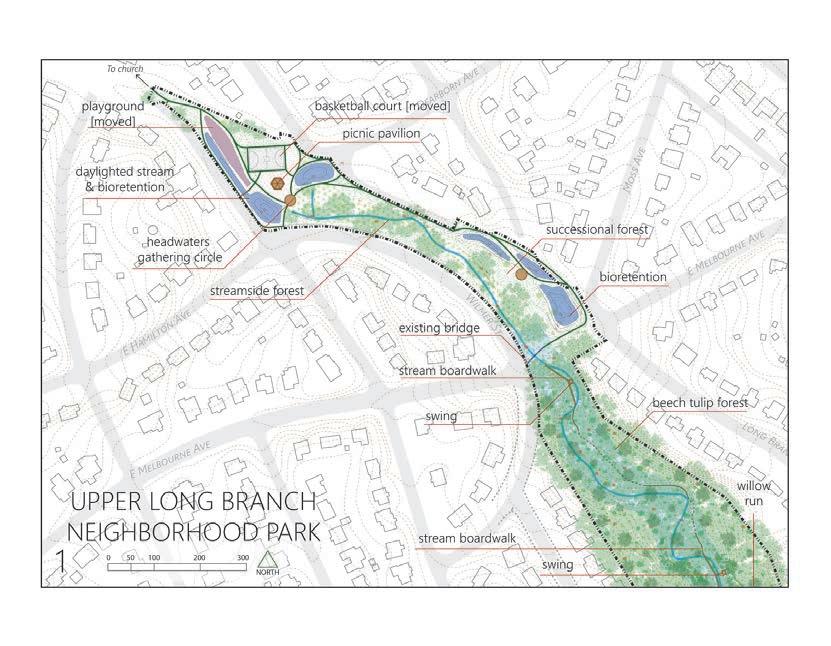

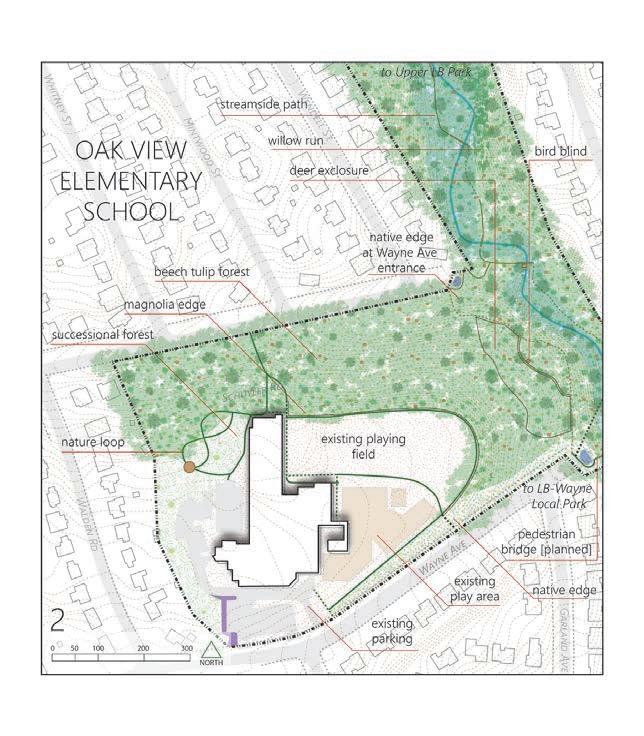

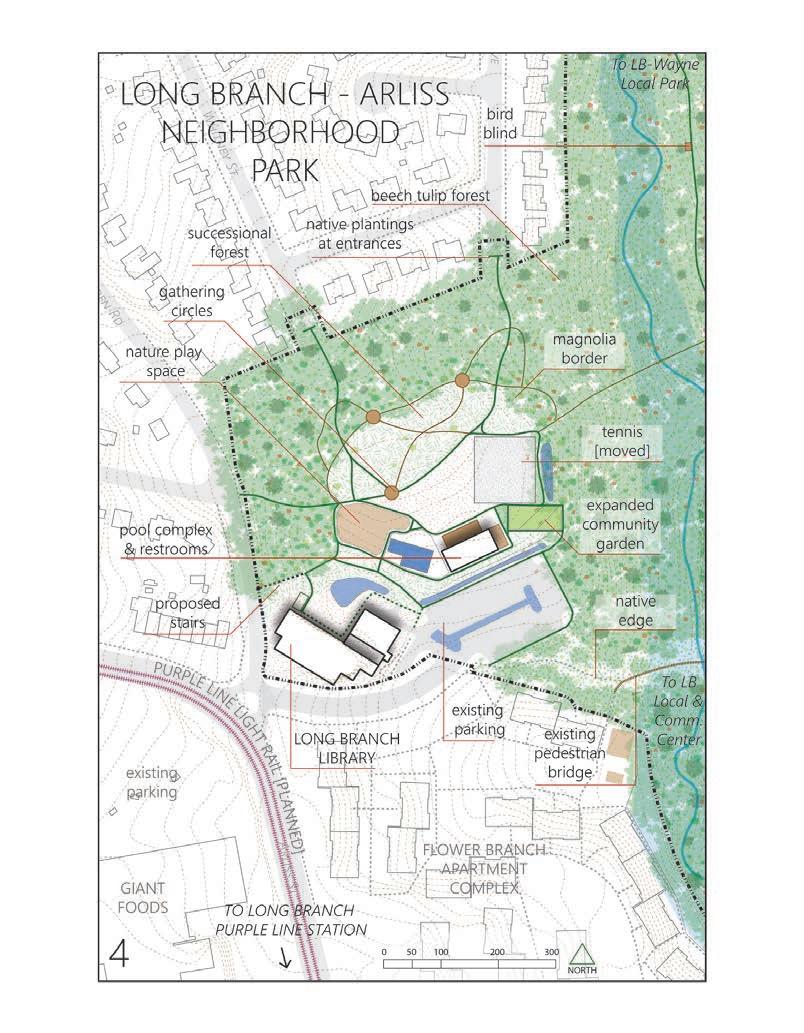

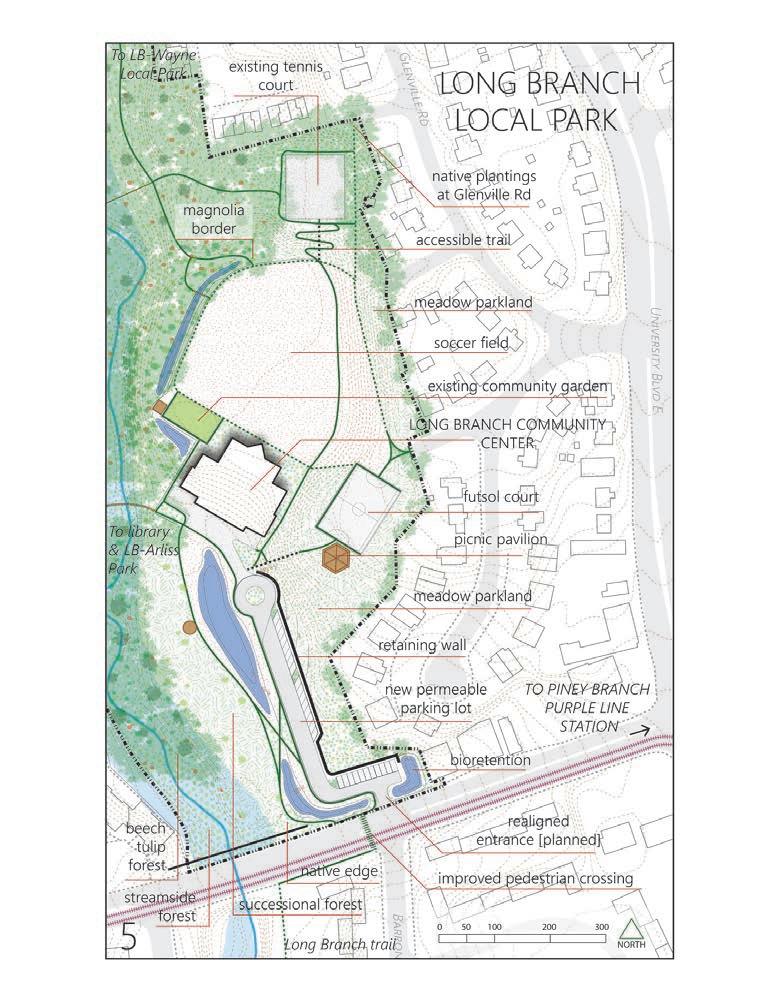

SITE PLAN: UPPER LONG BRANCH PARKS

The site plan was divided into five sections. In four sections there is an existing park, and in one there is an elementary showing the proposed plan for each park, which is intended to meet community needs, expand the capacity more visitors, and connect ecological quality of the

NORTH

ArcGIS, Adobe Illustrator

5

elementary school. This is a conceptual site plan capacity of the Long Branch forest patch to support connect the parks together while building the the forest patch.

NORTH NORTH NORTH

9

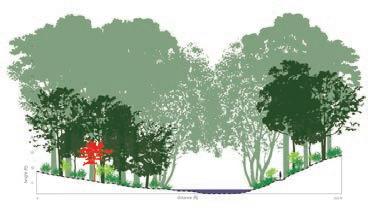

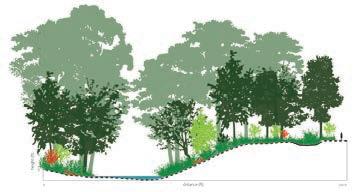

SELECTED PERSPECTIVES: LONG BRANCH STREAM VALLEY

SketchUp, Adobe Photoshop

10

11

SELECTED PERSPECTIVES: LONG BRANCH STREAM VALLEY

SketchUp, Adobe Photoshop

SketchUp, Adobe Photoshop

12

13

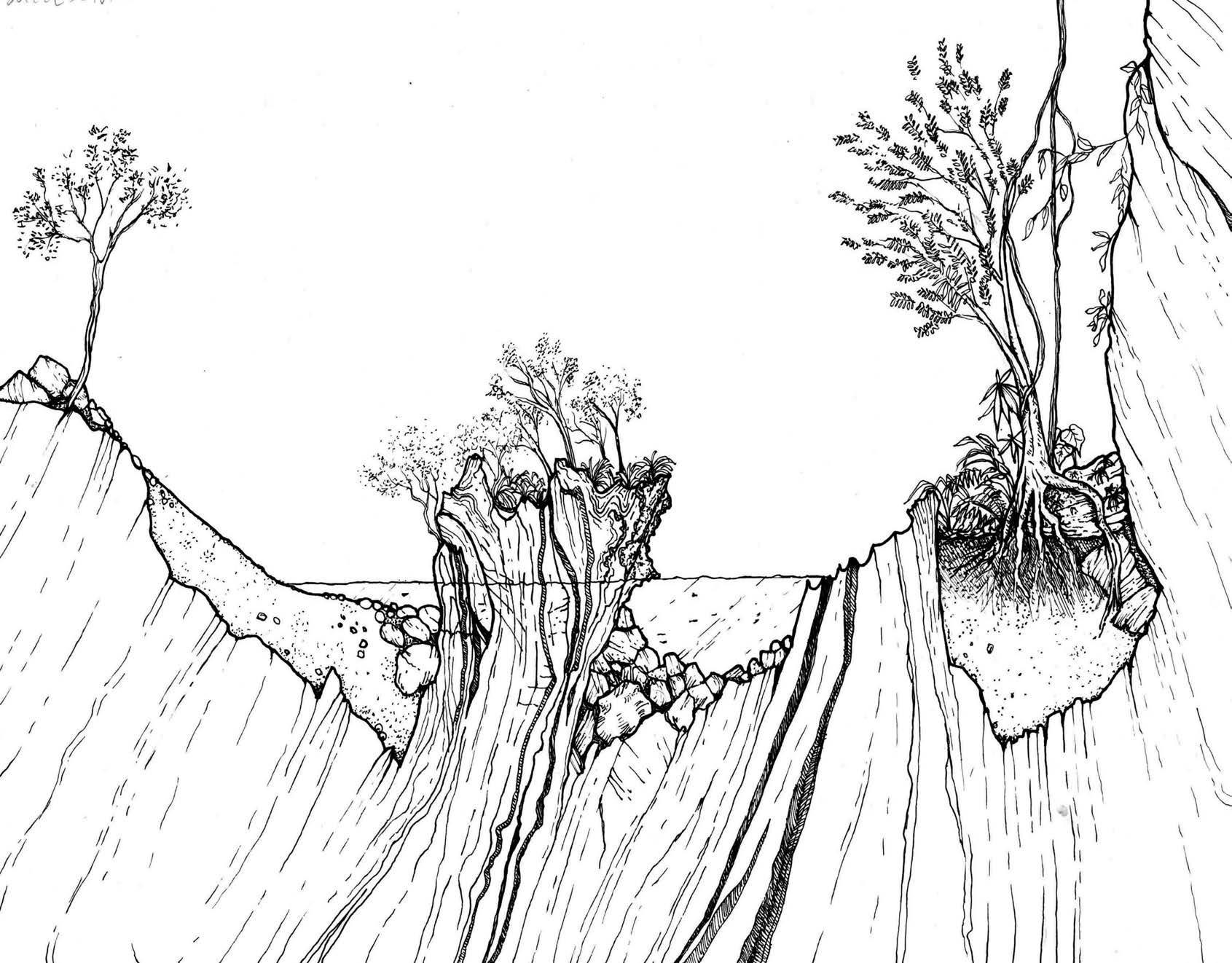

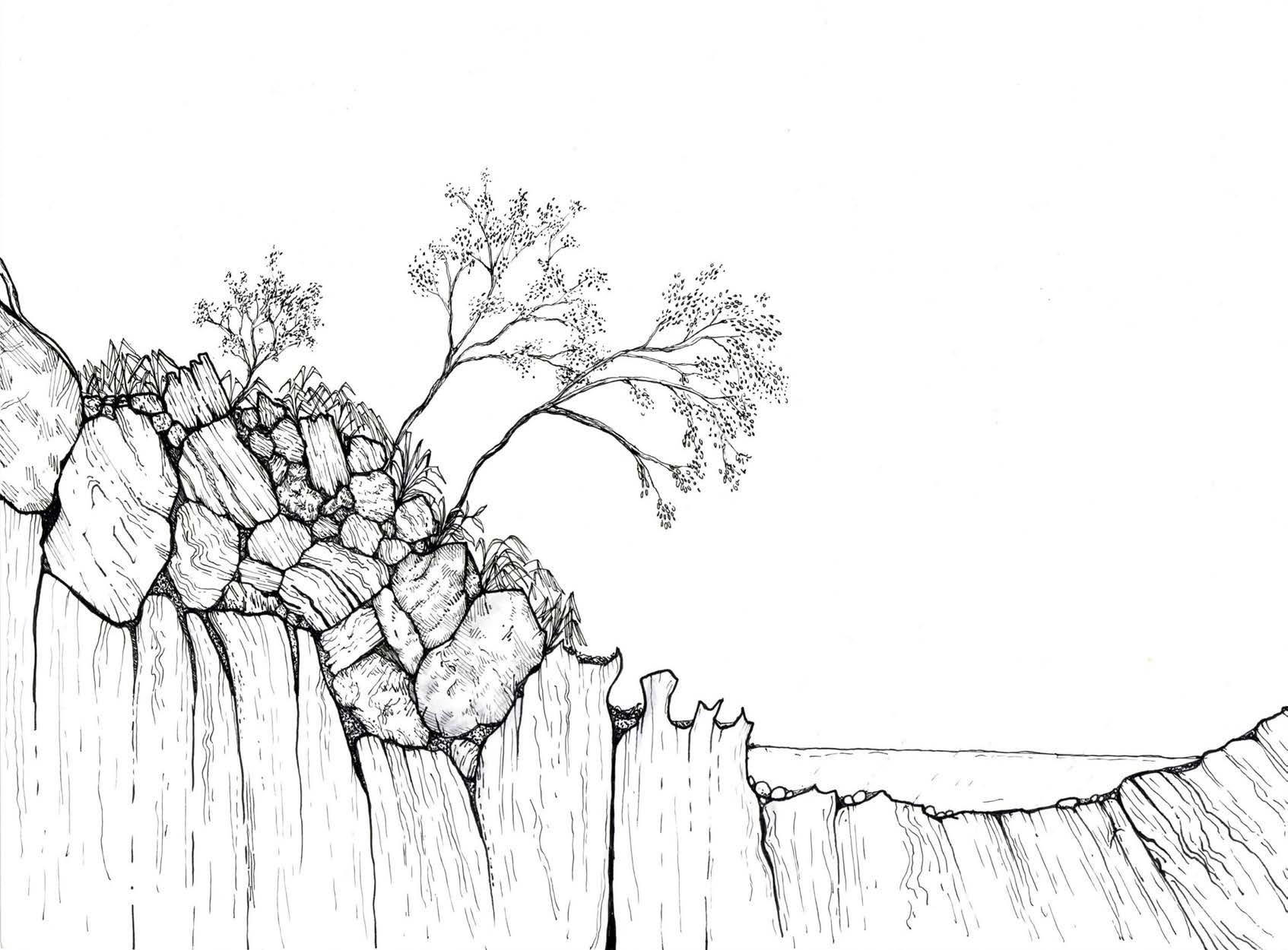

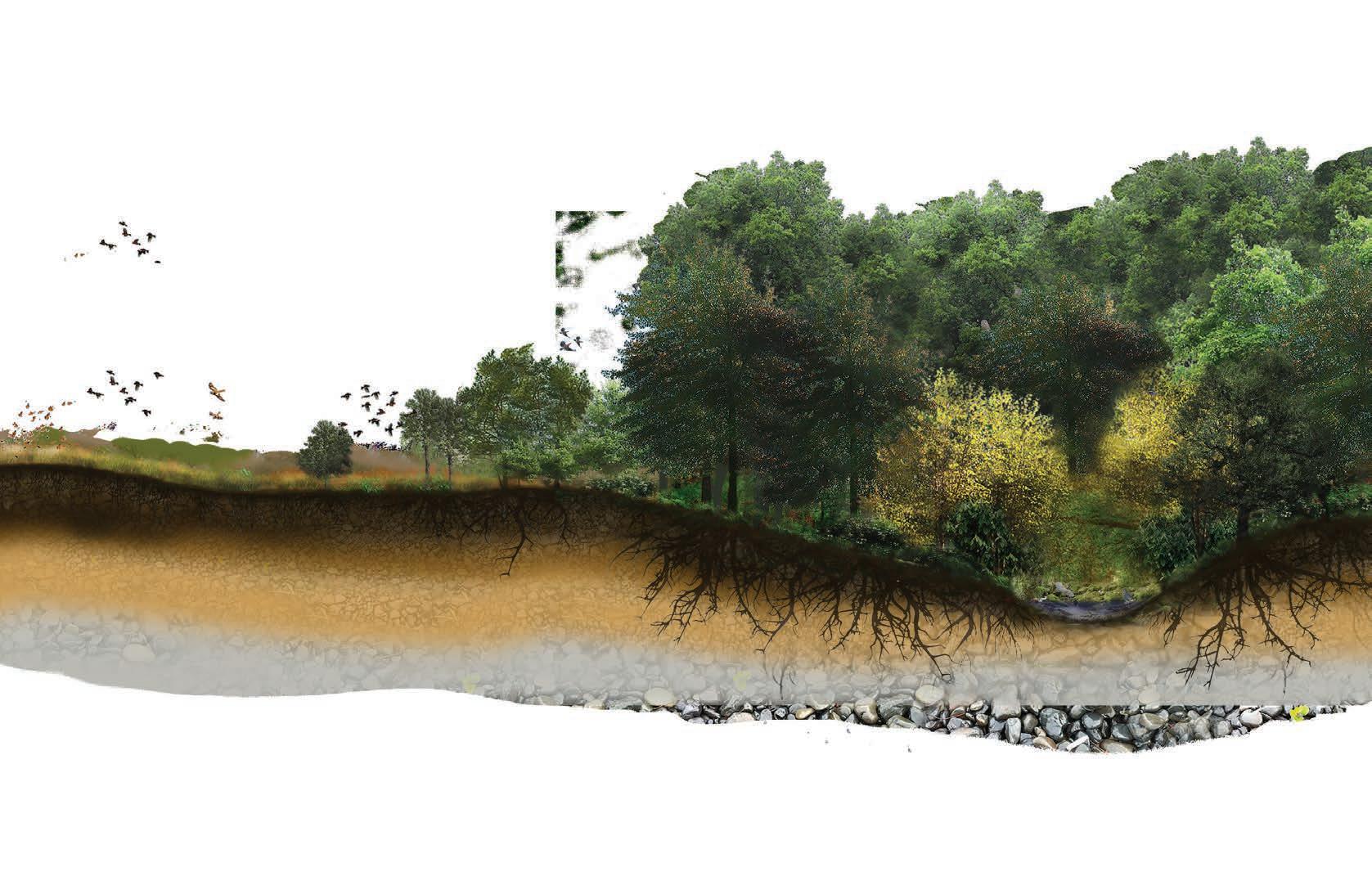

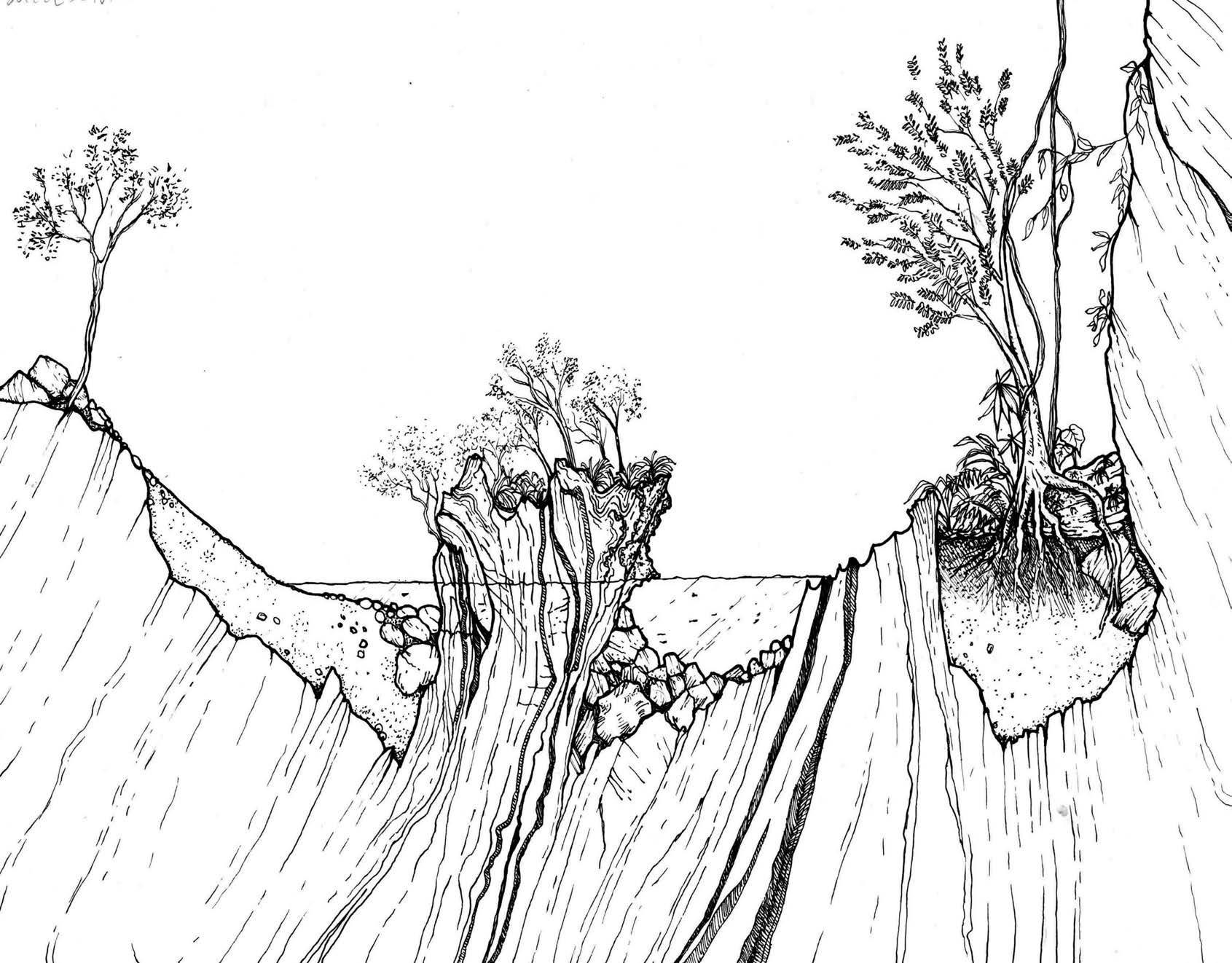

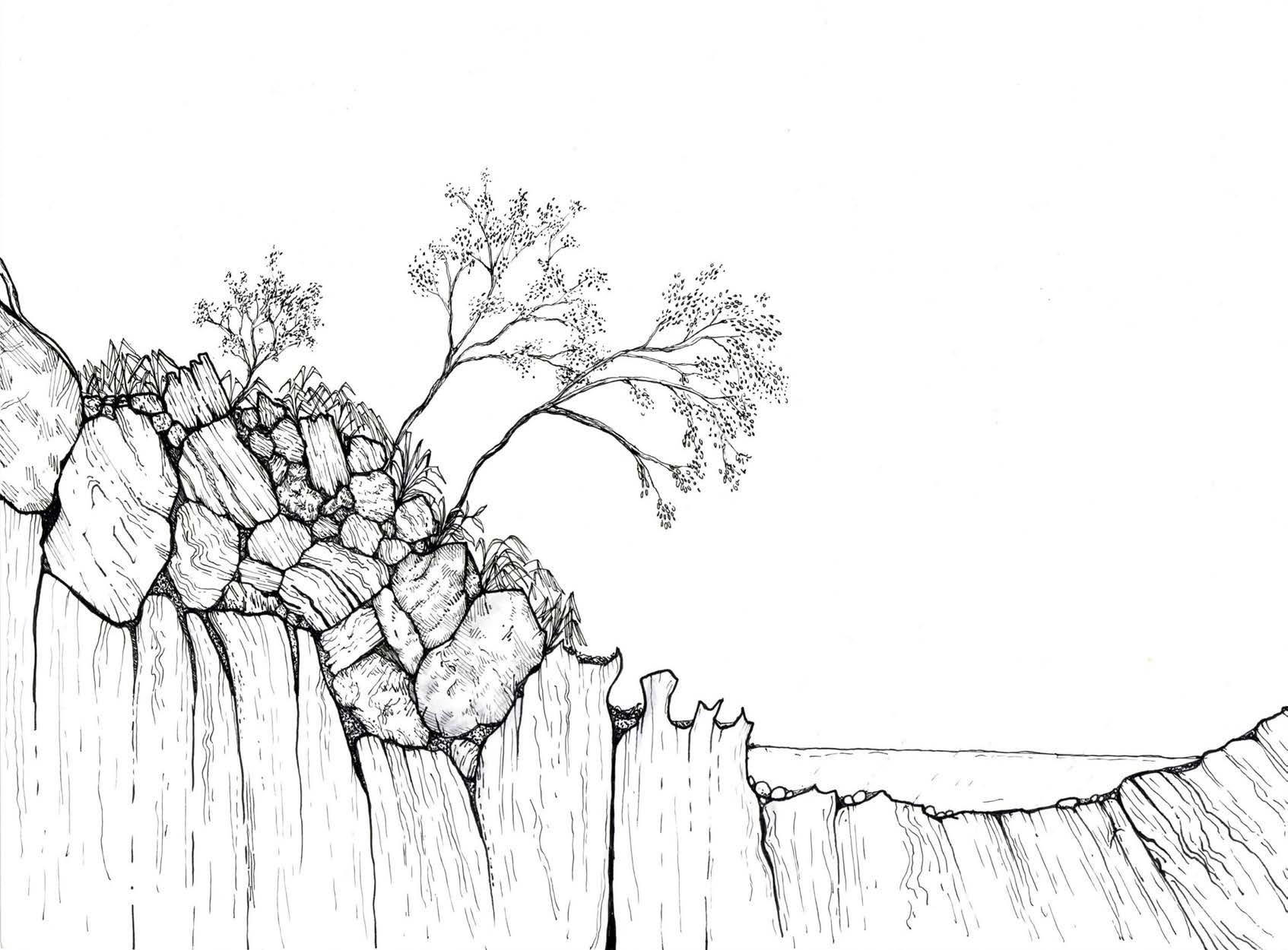

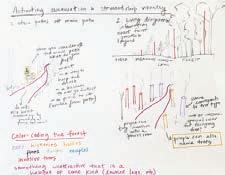

READING THE LANDSCAPE: RÍO CLARO

PROJECT TYPE:

LOCATION:

TOOLS:

Field-based fellowship project

Rio Claro Forest Reserve, Antioquia, Extensive site observation, hand drawing,

This project was done Antioquia, Colombia. Through conceptual illustration visible landscape components to the biological on science to communicate embedded cues in

DESCRIPTION:

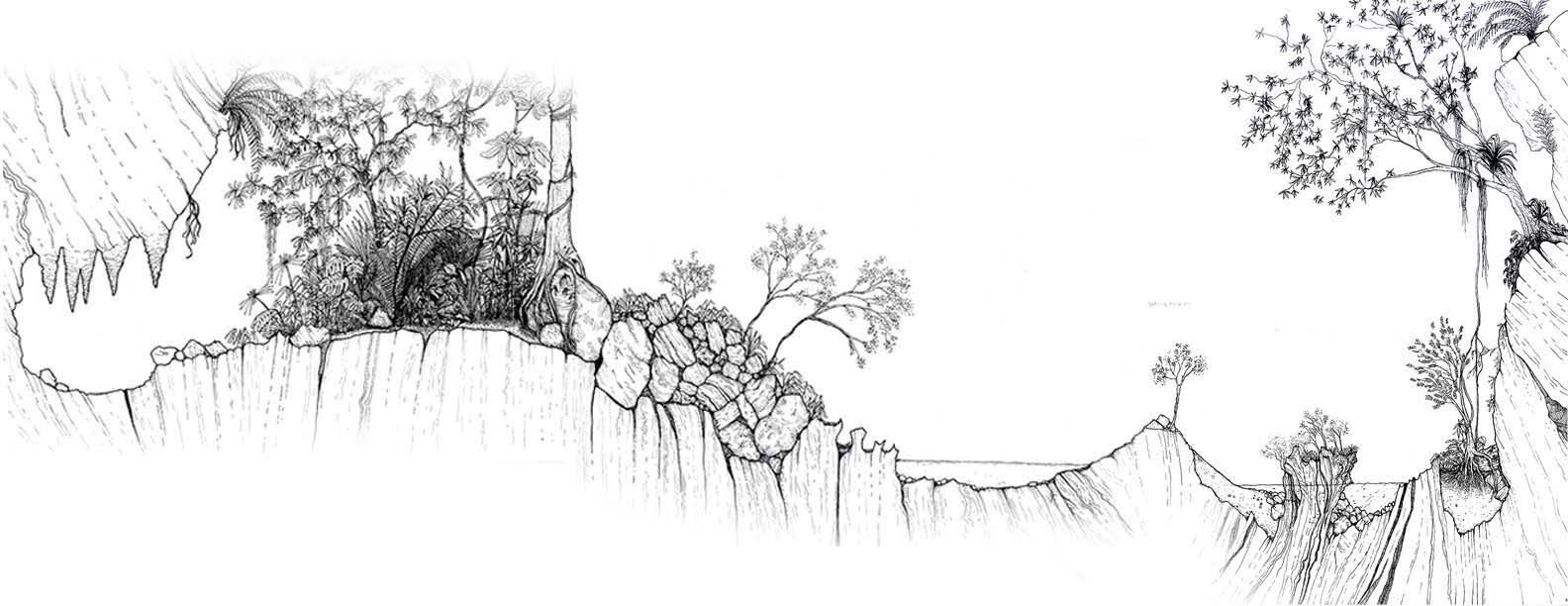

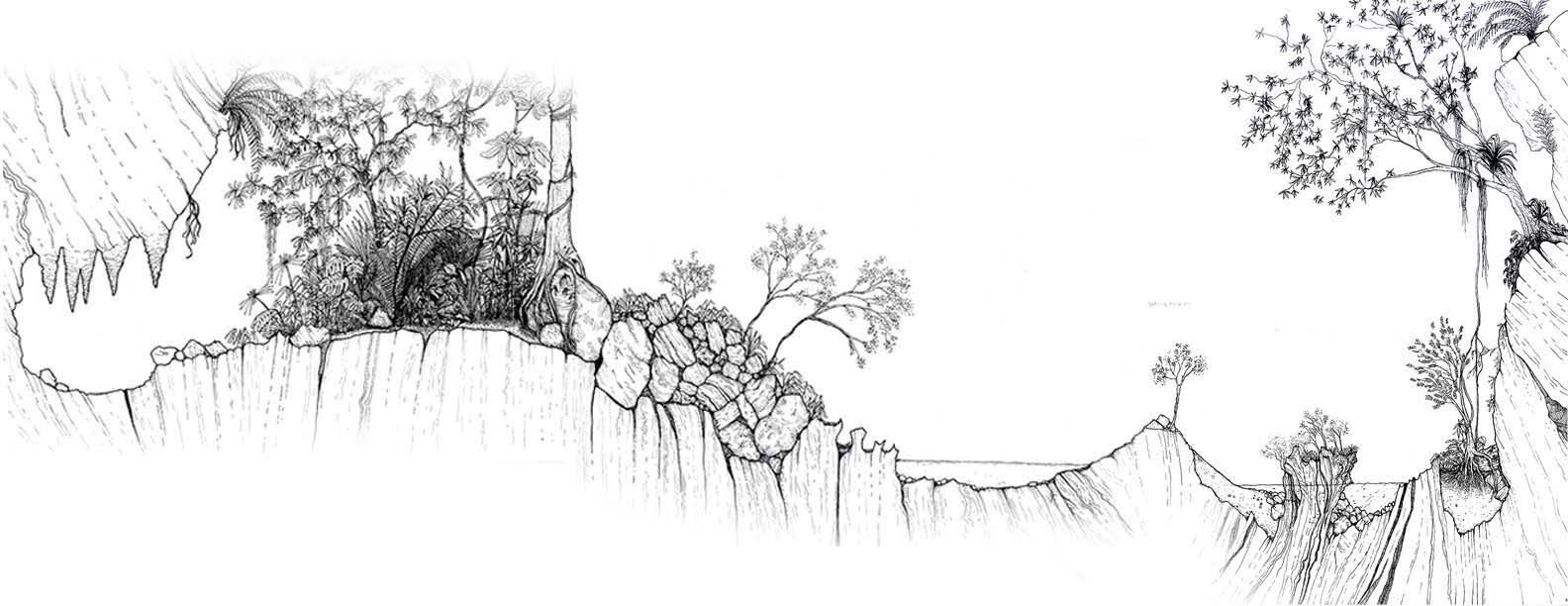

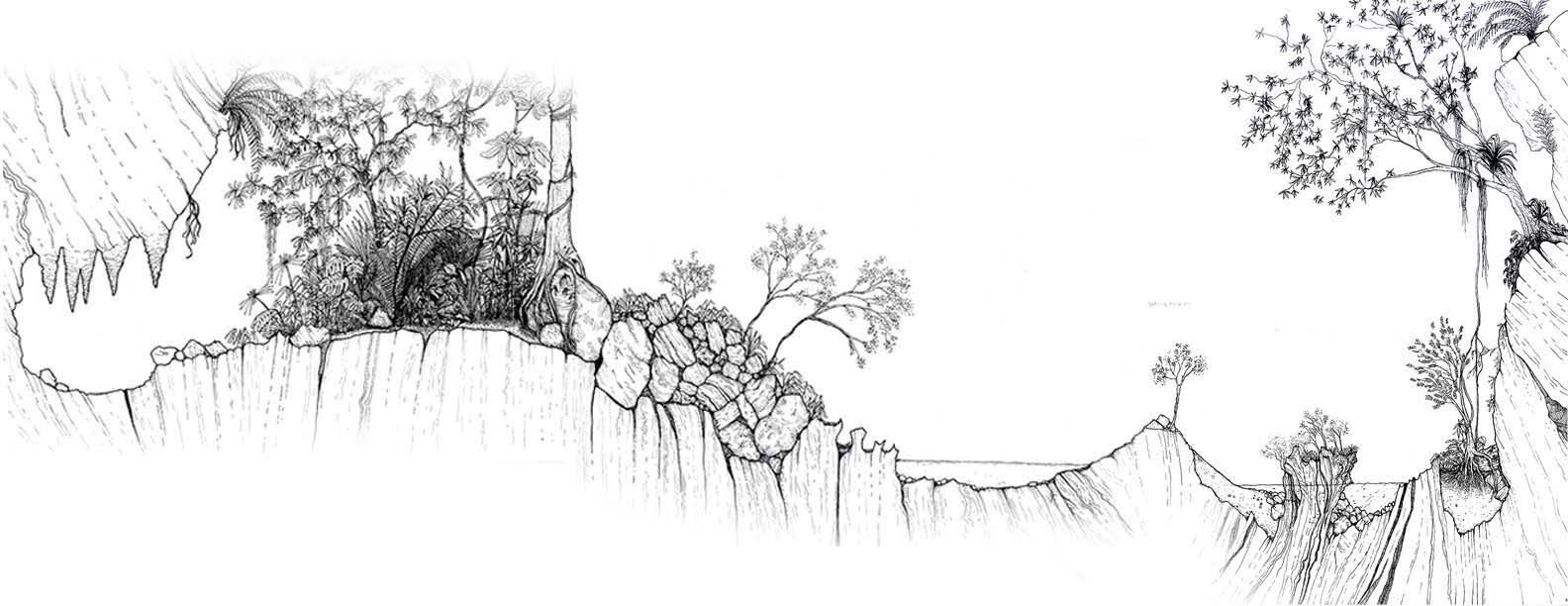

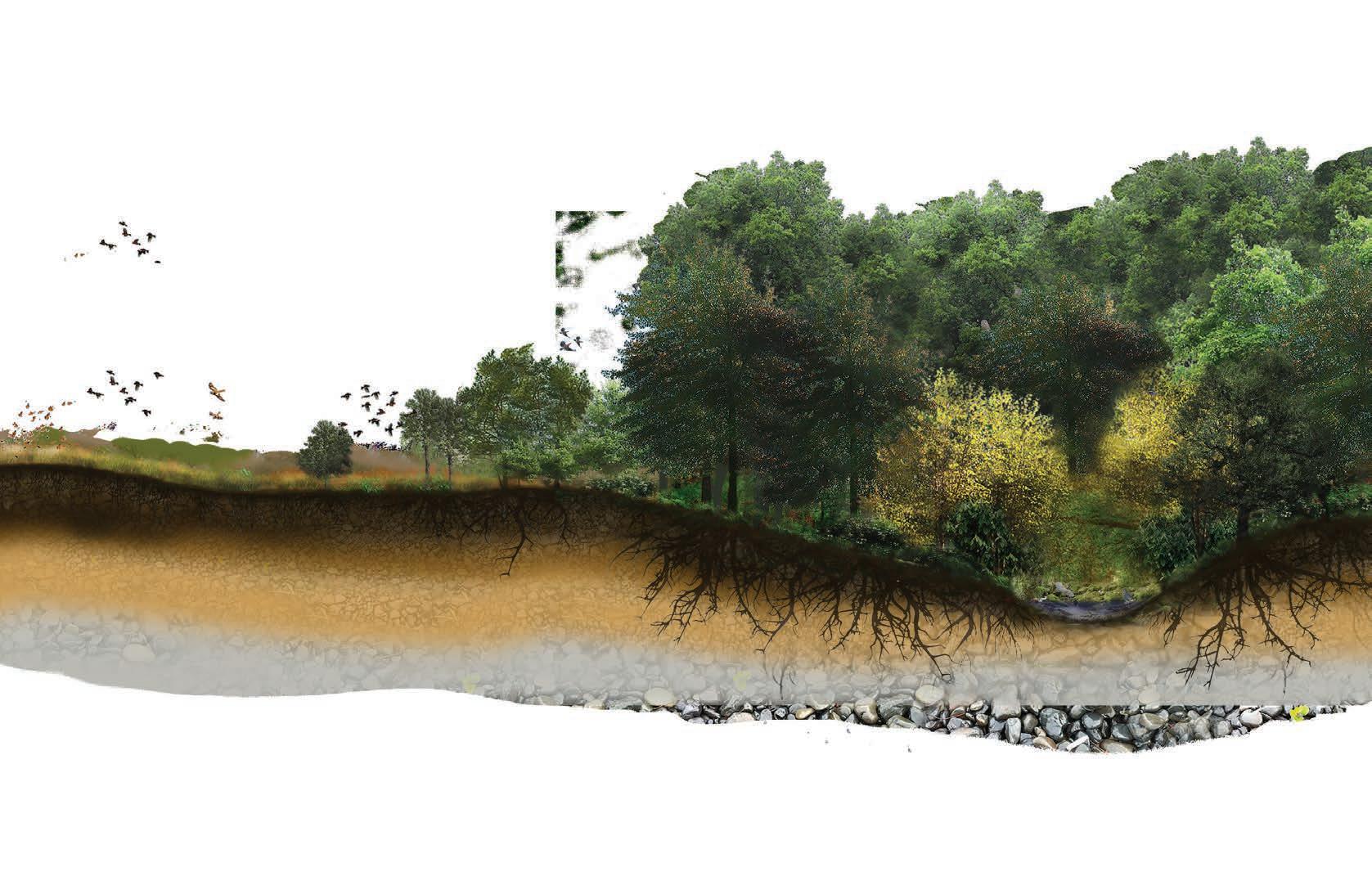

DEEP SECTION: RIO CLARO

Freehand pen

Some of the biological and geological phenomena the river carved through its marble karst bedrock biogeographical conditions in this region contribute

early plantszombie

stalactitesfungal competitionheliotropismextreme endemism

caverns

parasitismant

14

Antioquia, Colombia

drawing, Adobe Photoshop, Illustrator, InDesign

during an interdisciplinary summer fellowship with the Wright-Ingraham Institute in illustration and diagramming of landscape phenomena at varying scales, I aimed to connect biological and geological processes that shaped them. Though this is not a scientific study, it draws in the landscape that are indexical of how this moment in history was shaped.

uniquehabitatskarst patterns of dissolution

phenomena I observed over two weeks of fieldwork are illustrated here. In the Rio Claro forest reserve, bedrock over millions of years while karstic soils developed on the marble cones above. The unique contribute to some of the highest levels of biodiversity in the world.

project

pen illustration

riverbed stones

twisted and fused rocks

large host trees

15

shaping of the canyon

16

WATERSHED, MINING & CONSERVATION CONTEXT CONNECTING LANDSCAPE CUES

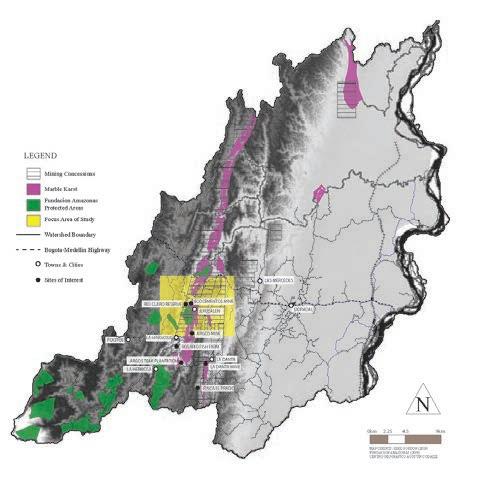

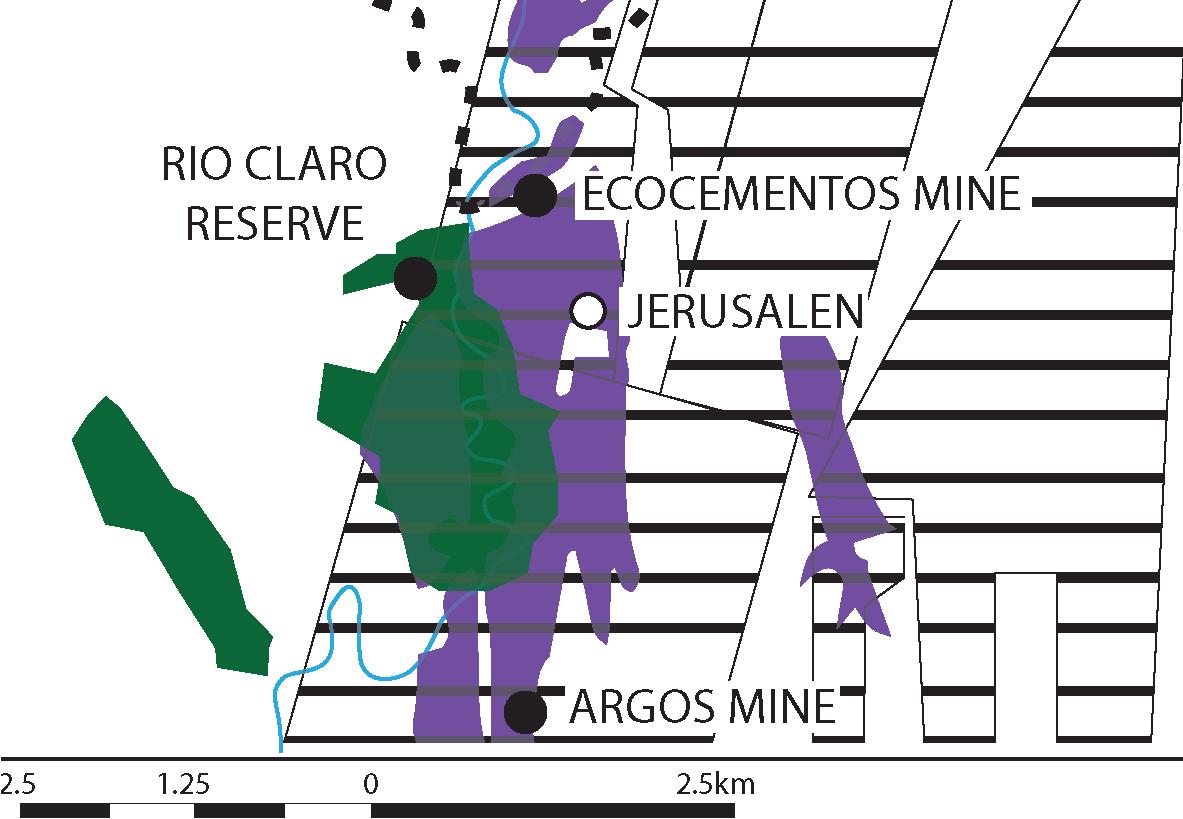

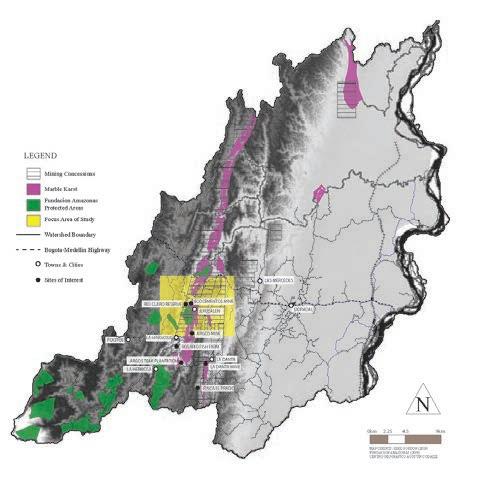

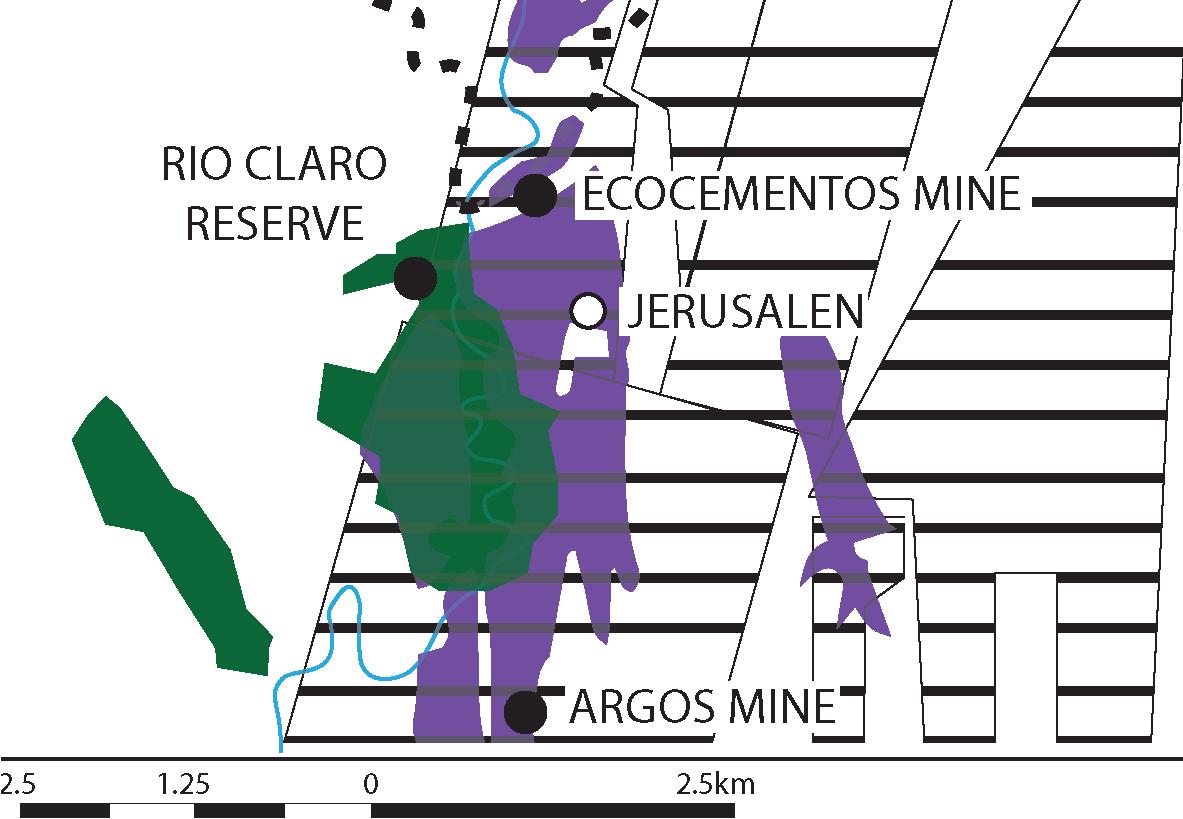

This watershed map shows the characteristic belt of marble through which the Rio Claro runs.

LEGEND

MINING CONCESSIONS

MARBLE KARST CLIFFS

PROTECTED AREAS

STUDY AREA

WATERSHED BOUNDARY

BOGOTA-MEDELLIN HIGHWAY

CITIES & TOWNS

PLACES OF INTEREST

The forests in this area are directly threatened by the marble mining industry.

443.8 419.2 358.9 298.9 251.9 PALEOZOIC MESOZOIC CENOZOIC QUANEOPALEOCRETJURTRI PERMCARBDEVSILORD 201.3 ~145 66 23.03 2.58 ERA PERIOD YEARS(MA)

first land plants and fish first amphibians first vertebrate land animals

The region is a large shallow ocean.

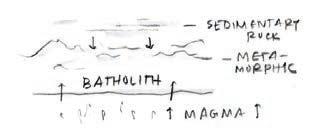

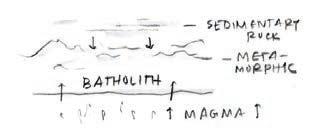

Central Andean Cordillera begins to form metamorphically

Shale forms from clay & silt compaction

Intrusive gneiss forms metamorphically

This timeline, split into three different time Linking the visible elements of the landscape the main processes that shaped this phenomena

Intrusive igneous rock formationdiorite and quartz diorite

Nazca plate moves under South American plate

Heat and pressure from batholiths create marble and schists

Andean cordilleras form; Marble & other rocks exposed to surface through uplift

BIOLOGICAL PHENOMENA

Repeated volcanic eruptions - El Nevado del Ruiz

MASS EXTINCTION MASS EXTINCTION MASS EXTINCTION MASS EXT. MASS EXTINCTION Colors were used in accordance with the International Chronostratigraphic Chart. EROSION AND DISSOLUTION WORLD RIO CLARO REGIONAL

Karst

Elements

Map credit: Kirk Gordon, Centro Geografico Augustin Codazzi

Map credit: Kirk Gordon, Centro Geografico Augustin Codazzi

Massive limestone deposits continue to form Pangaeaforms Age of reptiles dinosaurs dominate first flowering plants Atlantic Ocean opens Diversification of mammals Early hominids

Karst cones form through erosion and dissolution

MILLIONS OF YEARS

Flowering plant evolution

First land plants

ArcGIS, Adobe Illustrator

CUES TO GEOLOGICAL AND

Quaternary speciation

evolution

Intrusive diorite

Intrusive gneiss

Karst formation

RIO CLARO WORLD REGIONAL THOUSANDS OF

Marble karst cones are exposed; cliffs, caves, and reservoirs develop

Speciation driven by large-scale climactic shifts and complex geomorphology contributes to extreme endemism in neotropics & Rio Claro.

PAST SEVENTY YEARS

El Canon del Rio Claro

1970s: Mining companies route highways through karstic areas

1980: Mining concessions granted

1984: Highway completed; mining begins; nearby conservation land also acquired

1986: First major botanical inventory

1998-2005: Mass emigration from region due to armed conflict

2005-2008: Number of scientific & botanical studies increase

2008-present: 2016 peace deal increases access; marble mining activity intensifies

17

Rio Claro may have been part of the Dotted area No. 2: Nechi Pleistocene refuge. From Haffer (1969)

Rio Claro may have been part of the Dotted area No. 2: Nechi Pleistocene refuge. From Haffer (1969)

Earth vacillates dramatically between glacial and interglacial

periods, driving massive shifts in global biome distribution. EROSION AND DISSOLUTION

These changes drive speciation patterns in Neotropics. EROSION AND

Globalfluctuationstemperature DISSOLUTION MASS EXTINCTION

1950s: Forest cleared for cattle grazing

1966: Construction of Bogota-Medellin highway begins

YEARS

HOLOCENE ANTHROPOCENE 19501960197019801990200020102019 ERA PERIOD YEAR LATE QUATERNARY PLEISTOCENE ERA PERIOD YEARS(K) 600500400300200100

time scales, outlines biological and geological shifts that contribute to current-day conditions in the Canyon of Rio Claro. landscape with these historical processes adds a dimension of observable time. Leaders indicate the period of history when phenomena began.

Elements are arranged according to whether they are biological phenomena, geological phenomena, or an interaction between the two.

BIOLOGICAL HISTORY

GEOLOGICAL PHENOMENA

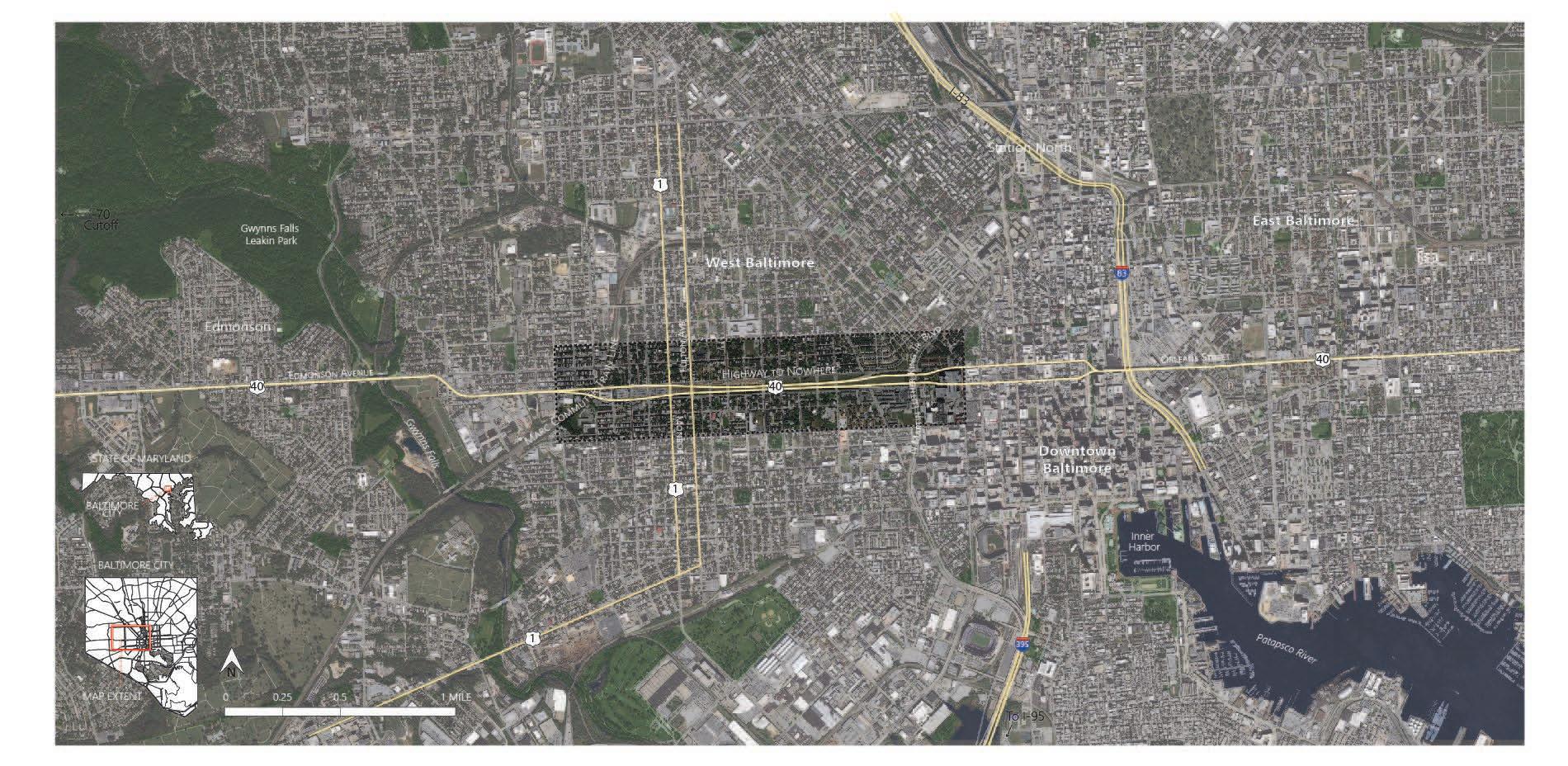

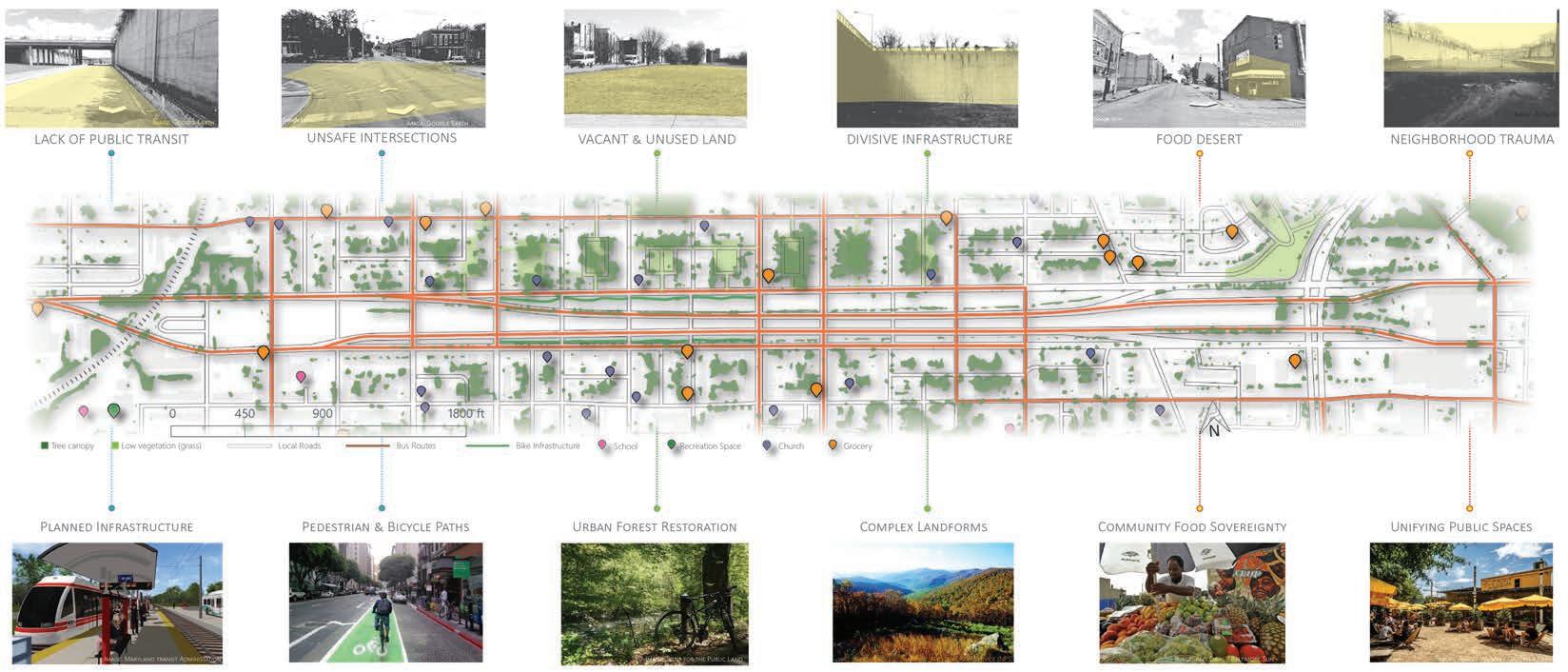

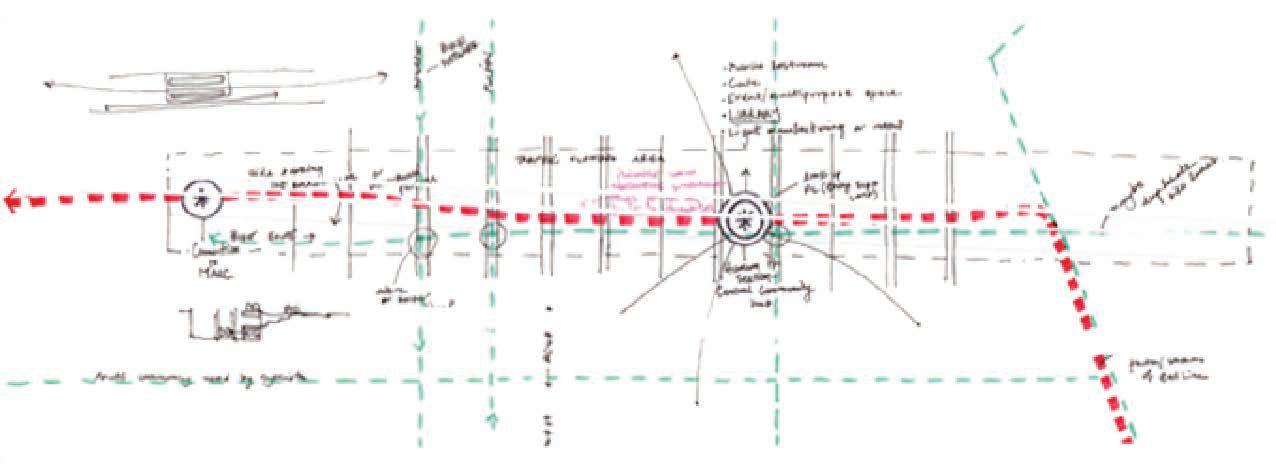

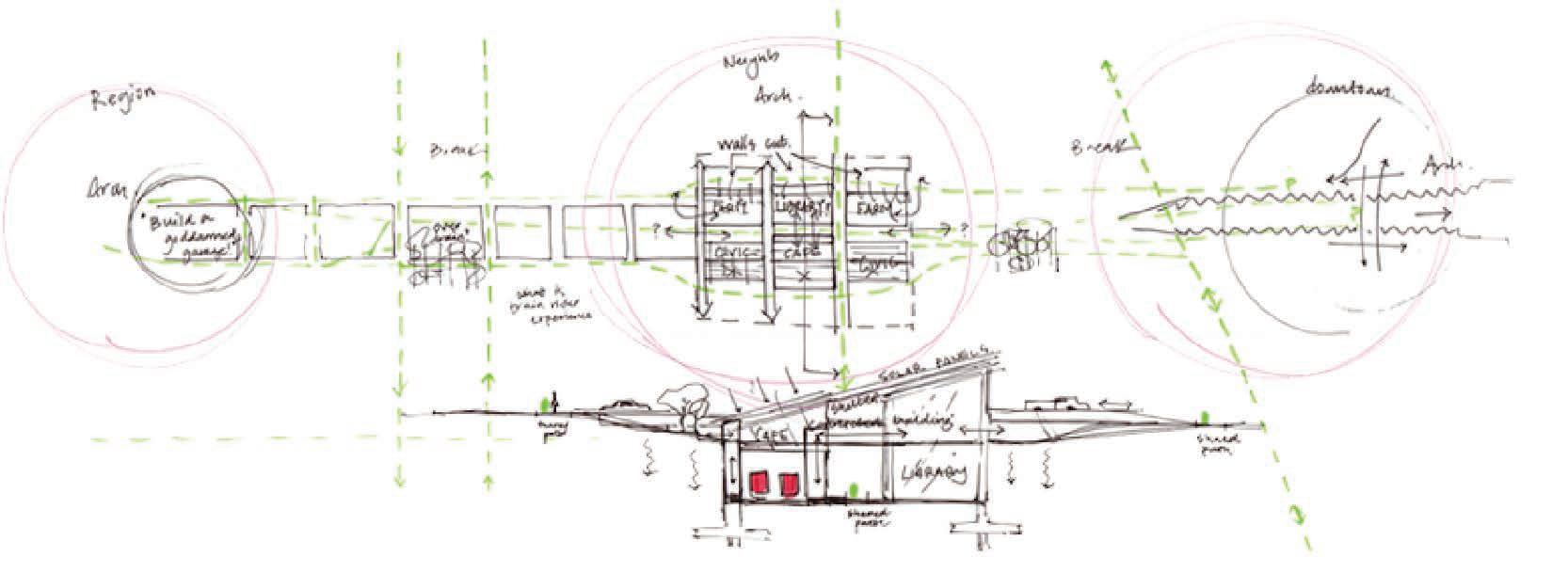

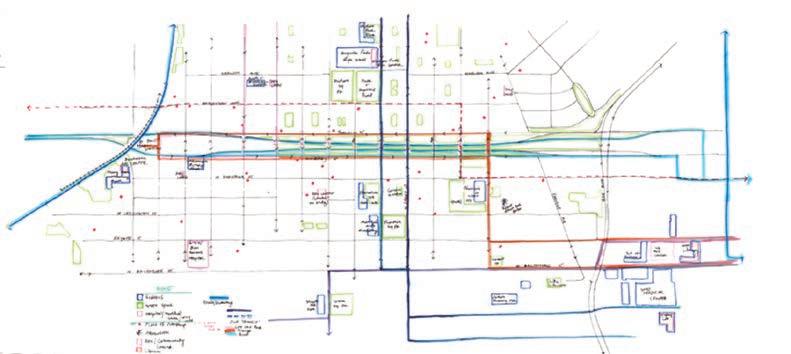

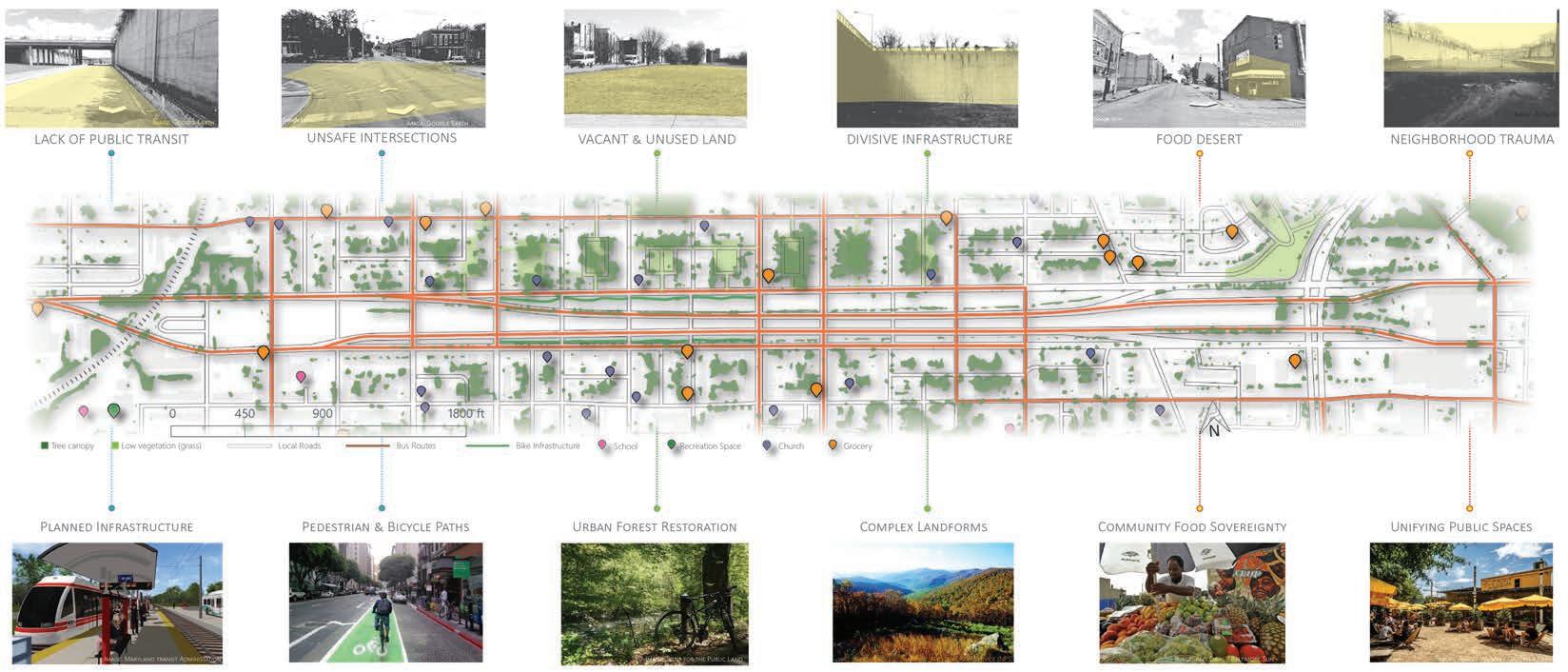

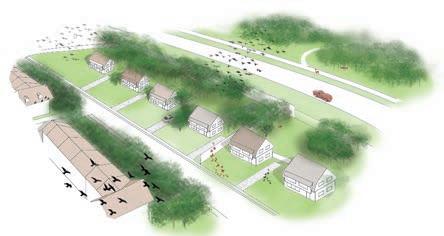

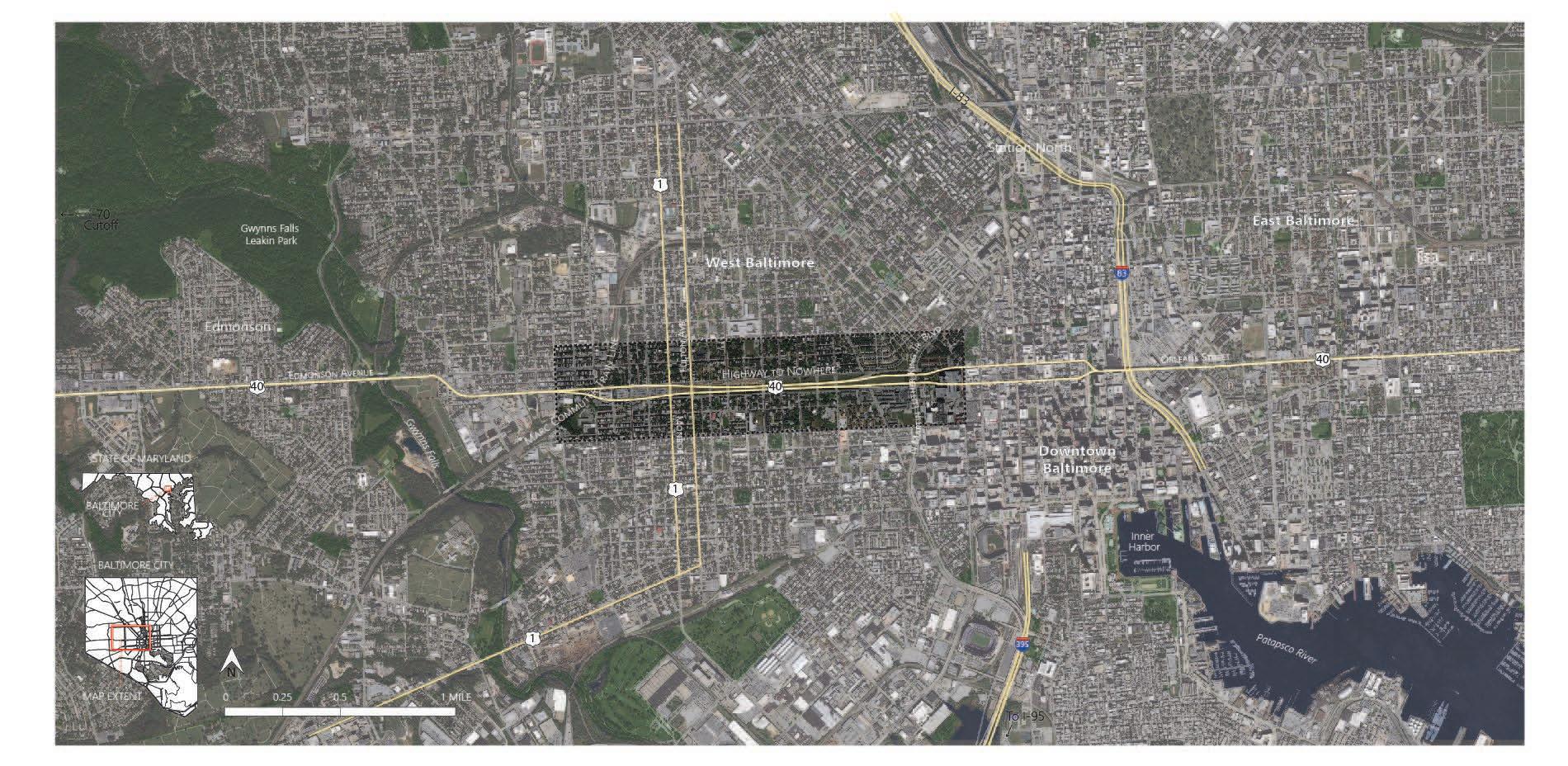

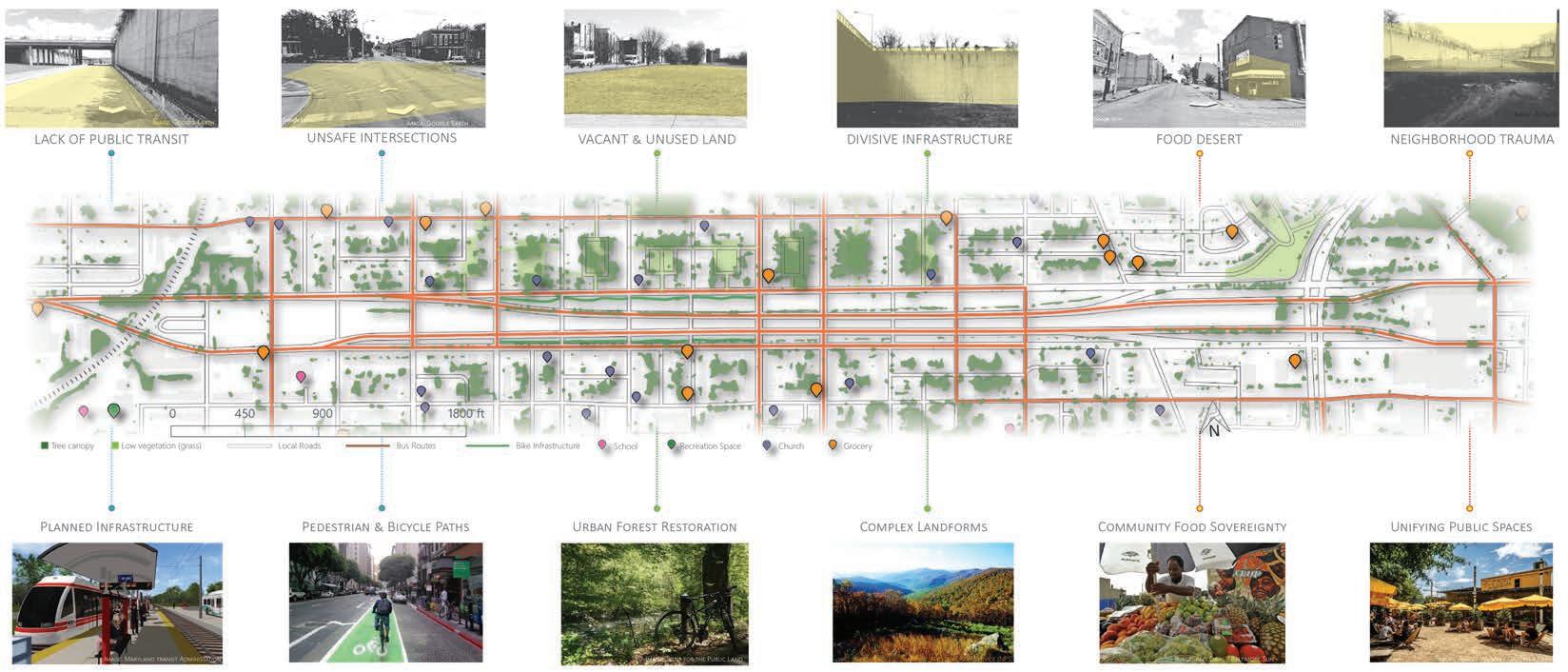

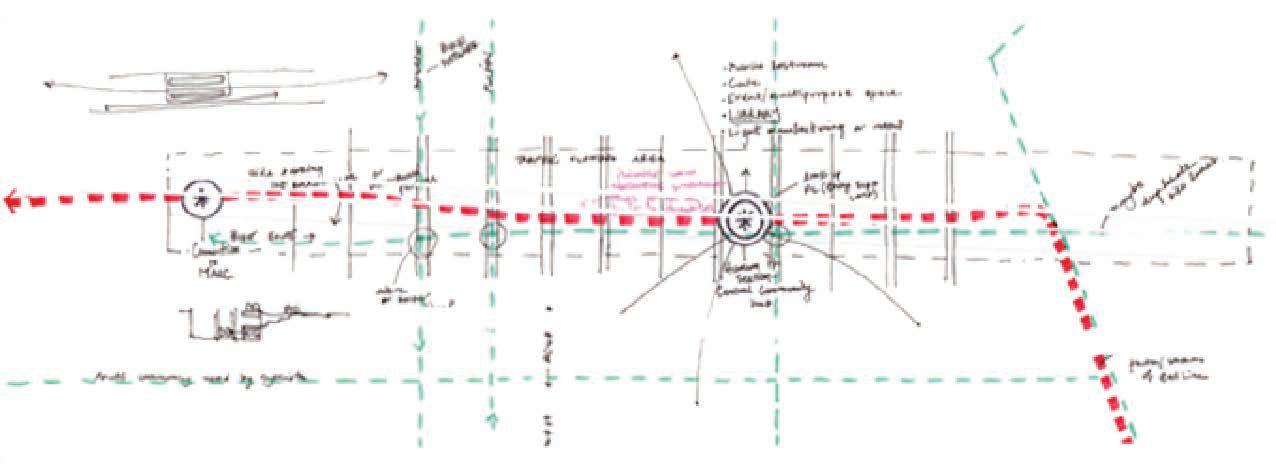

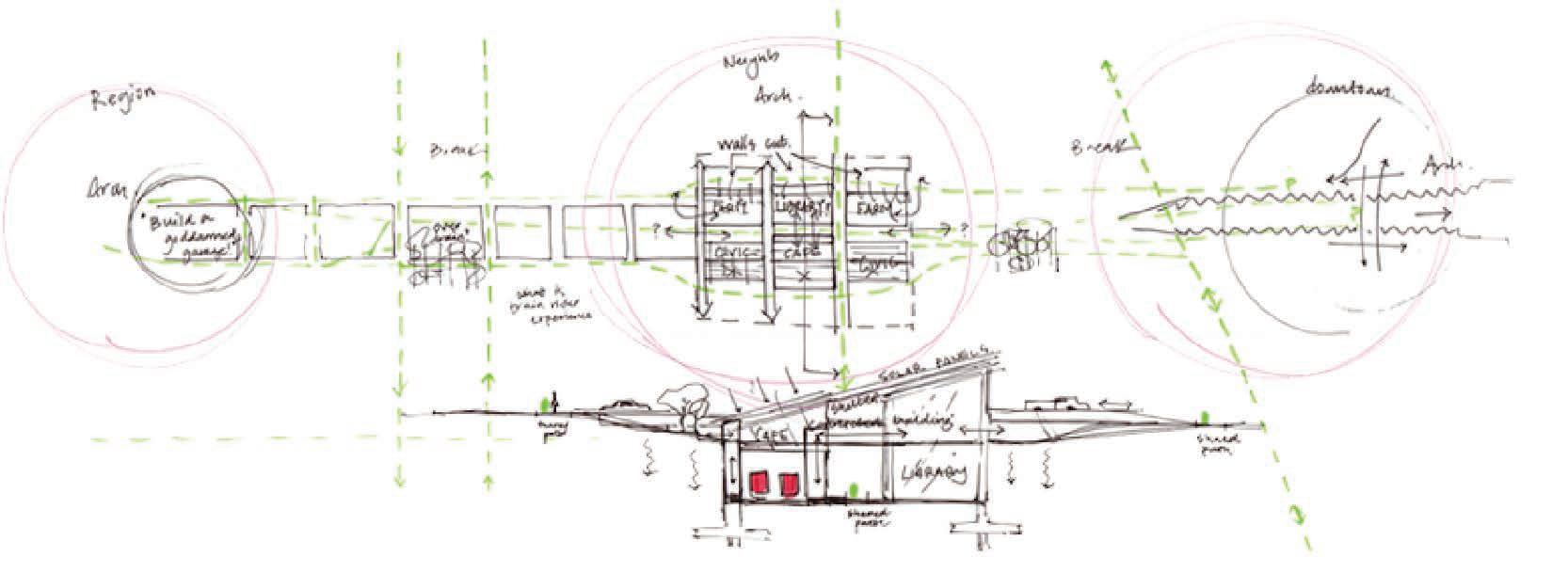

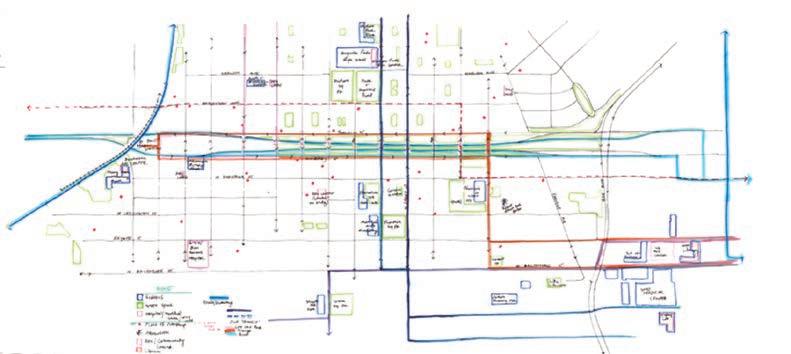

ROUTE 40 ECOLOGICAL PARK

PROJECT TYPE:

LOCATION:

Individual studio project

West Baltimore, Maryland

ROUTE 40: OPPORTUNITIES AND CONSTRAINTS

TOOLS:

ArcGIS, AutoCAD, Illustrator, Photoshop, InDesign, SketchUp, hand drawing

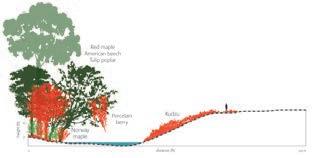

In West Baltimore, the so-called Highway to Nowhere tore a neighborhood apart when it was constructed in the mid-1970s. This project reimagines this underutilized space as a way to reconnect the neighborhood, build Baltimore’s green network, and integrate multimodal transportation.

DESCRIPTION:

ArcGIS, Google Earth, Adobe Illustrator

ArcGIS, Google Earth, Adobe Illustrator

18

PERSPECTIVE: WOODLAND PATH

Mixed Media

19

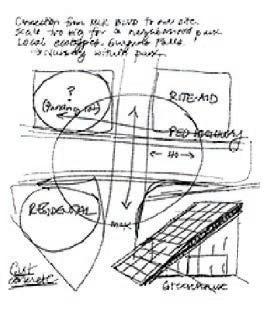

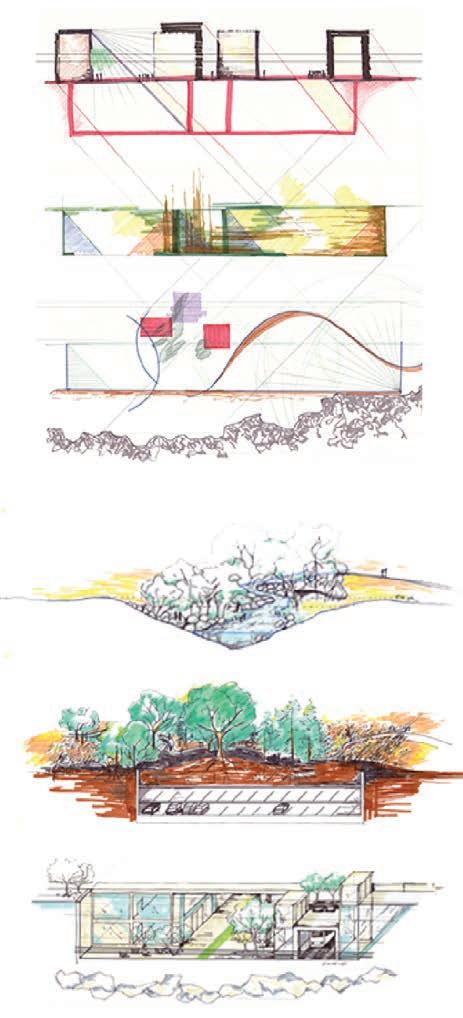

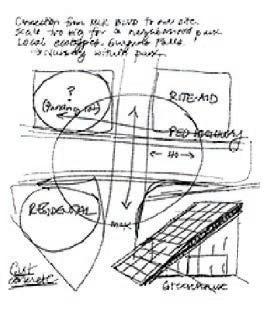

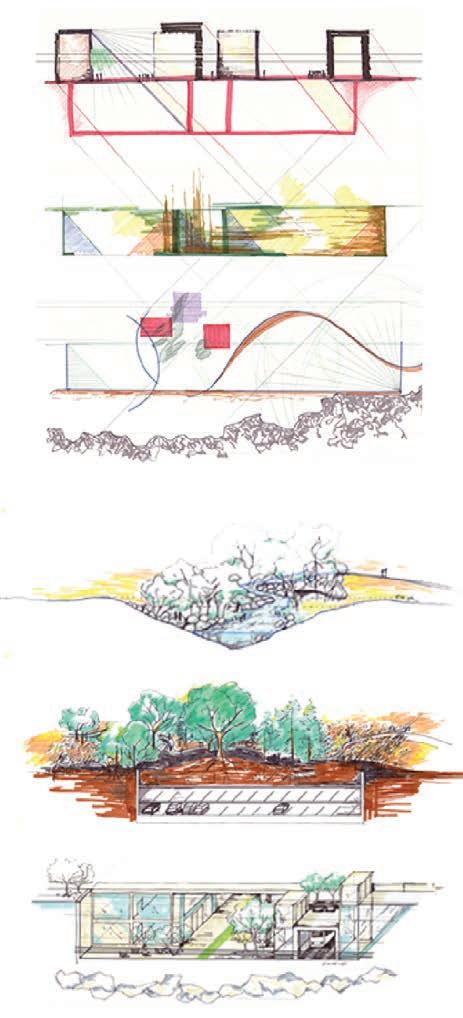

SKETCHES AND IDEATION

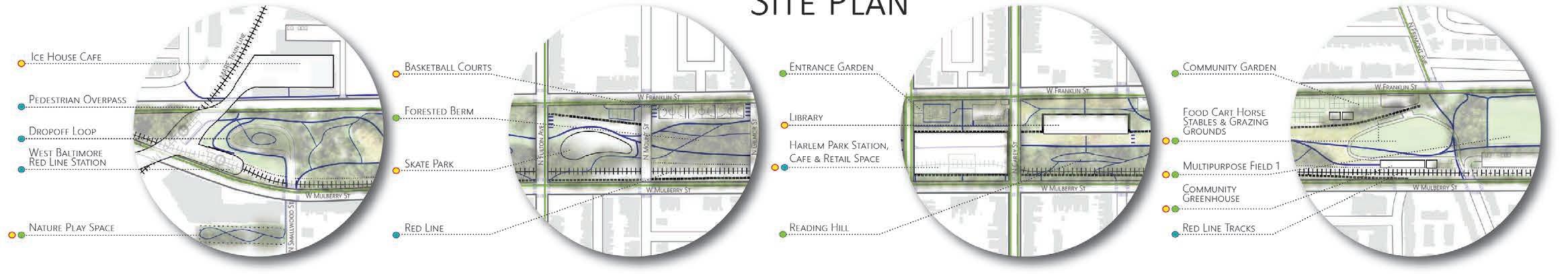

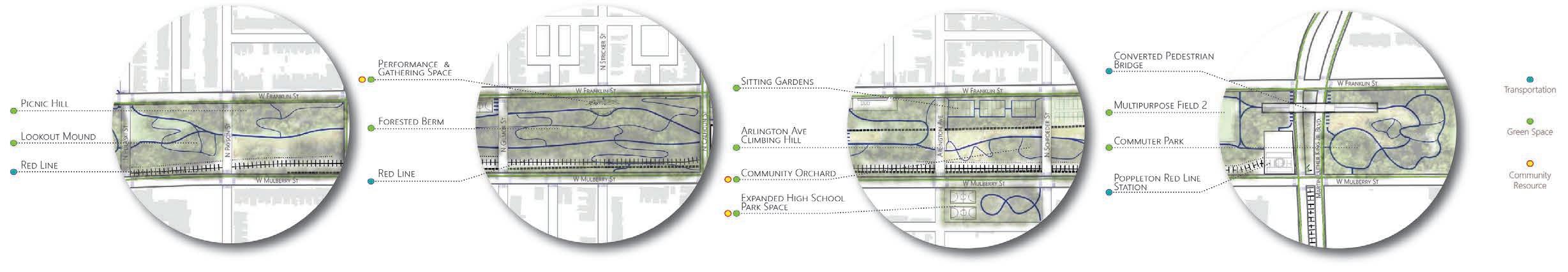

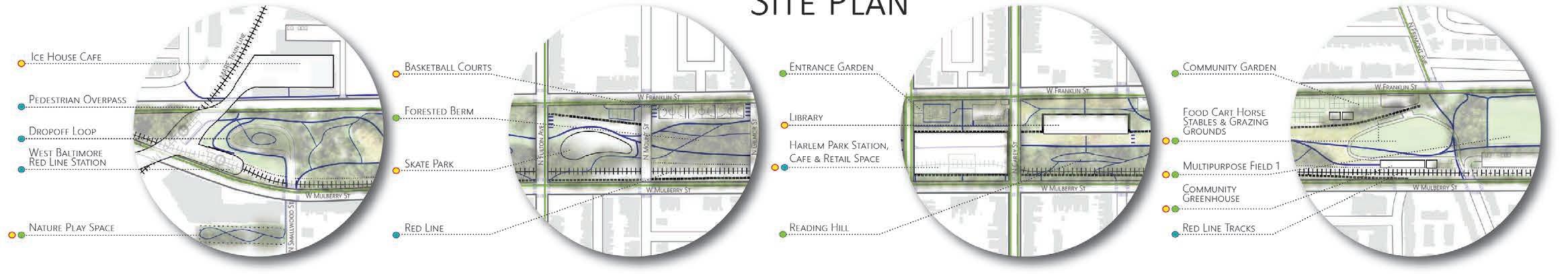

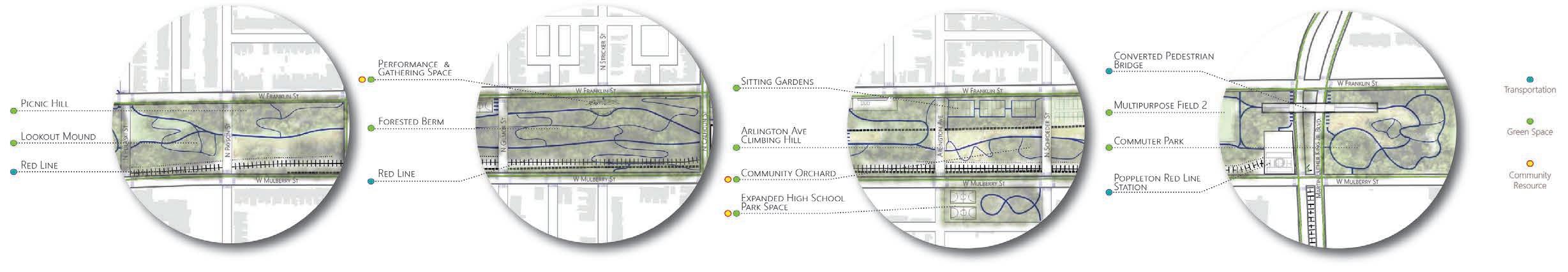

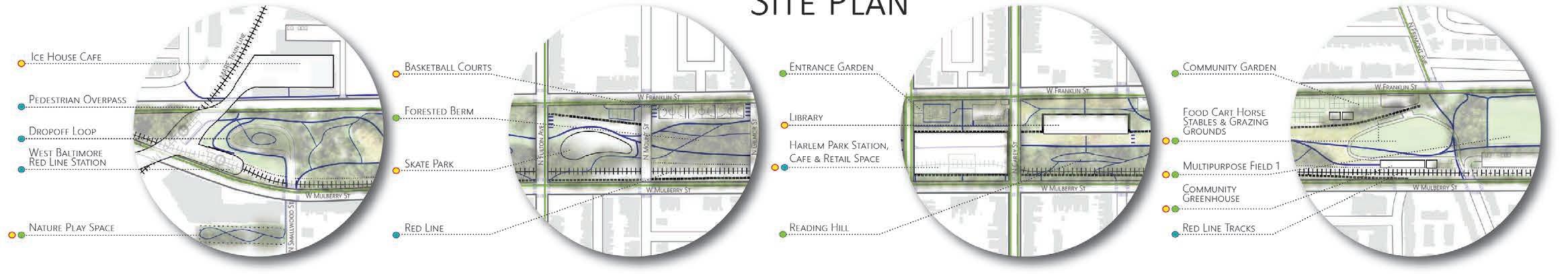

SITE PLAN: ROUTE 40 ECOLOGICAL PARK

ArcGIS, AutoCAD, Adobe Photoshop, Adobe Illustrator

LEGEND

VEGETATION

TRANSPORTATION

COMMUNITY RESOURCES

20

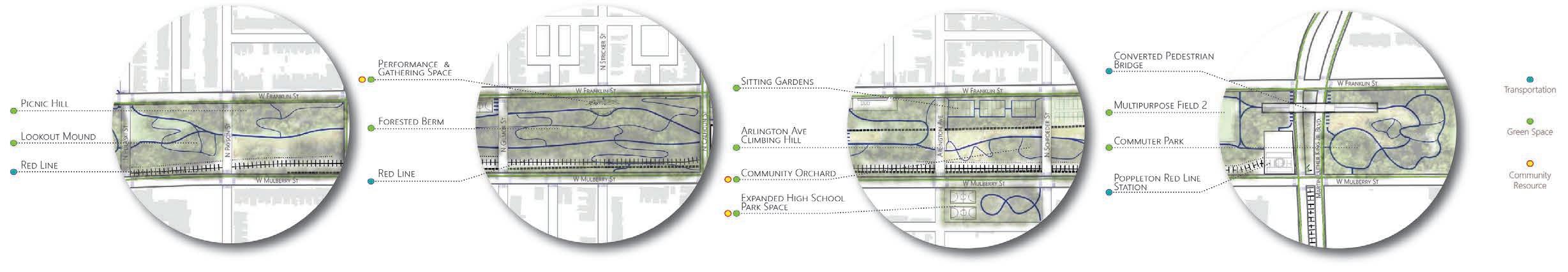

This conceptual plan weaves together planting design, multimodal transporation, and community resources. The planned (unbuilt) Baltimore Red Line light rail runs through the site. The design includes meadows, forested berms, and shrublands, space designated for local businesses, a community library, horse stables to uphold a fading part of West Baltimore’s history, community greenhouse and gardens, and a wide variety of recreational resources.

21

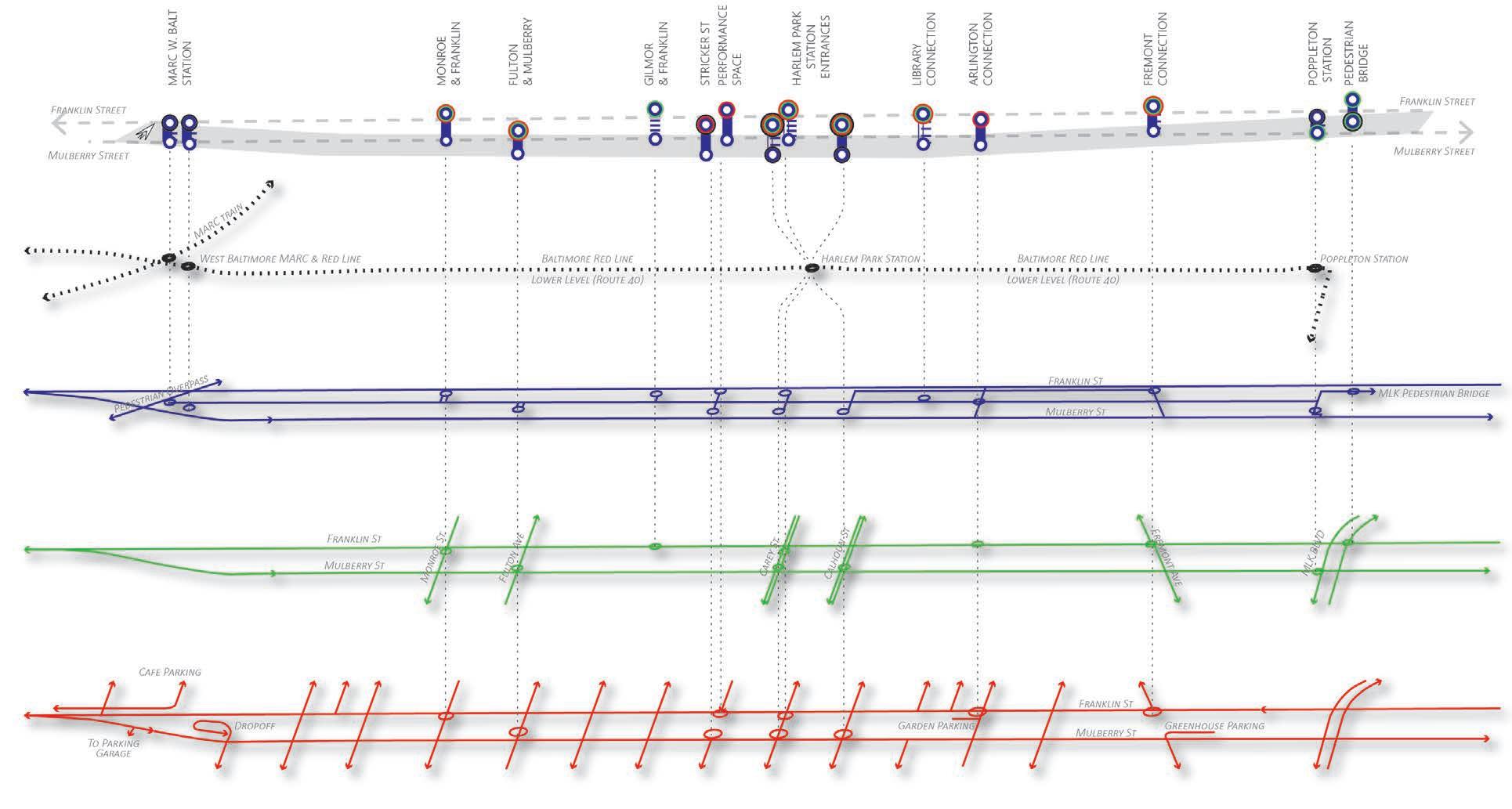

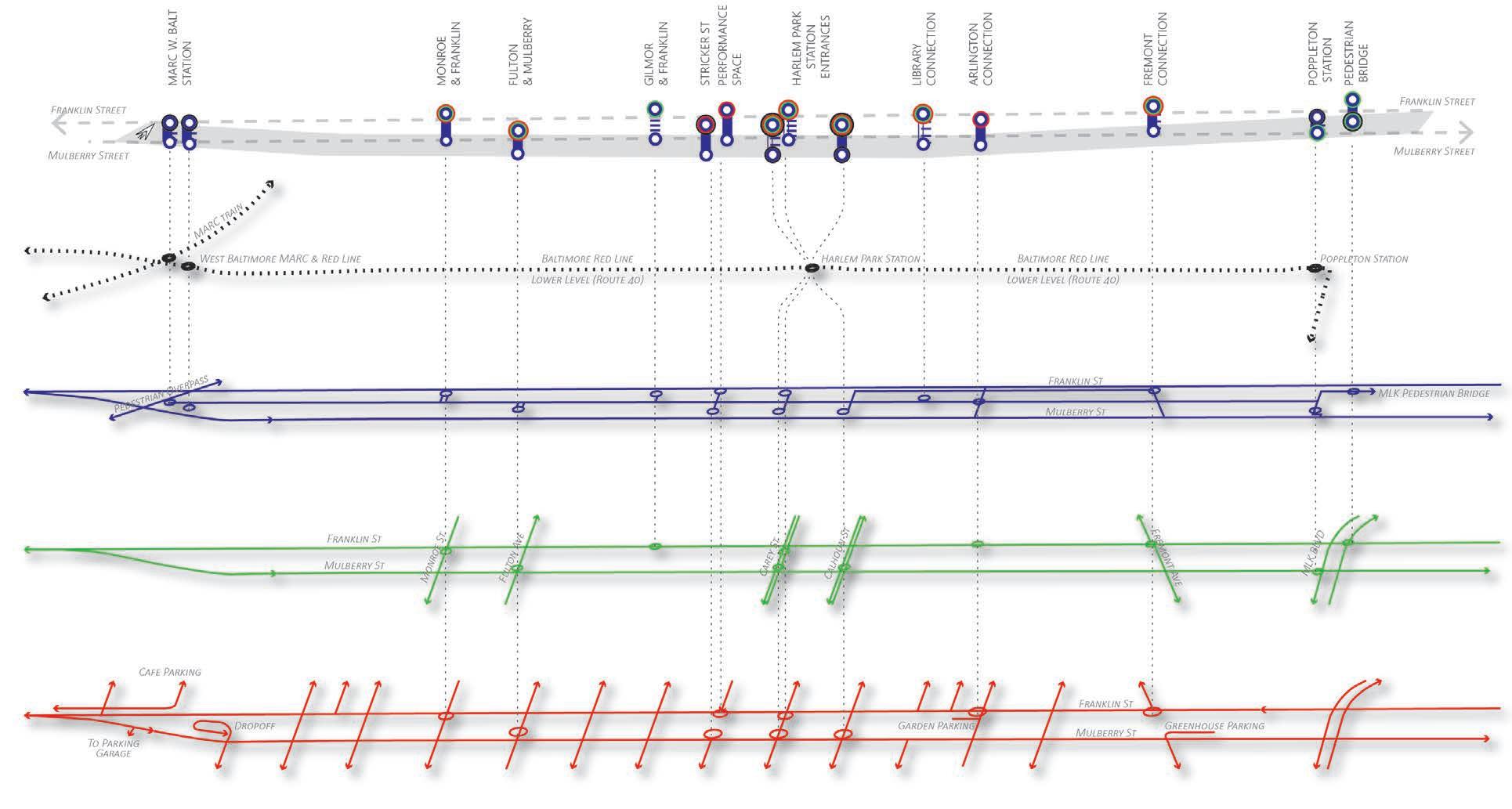

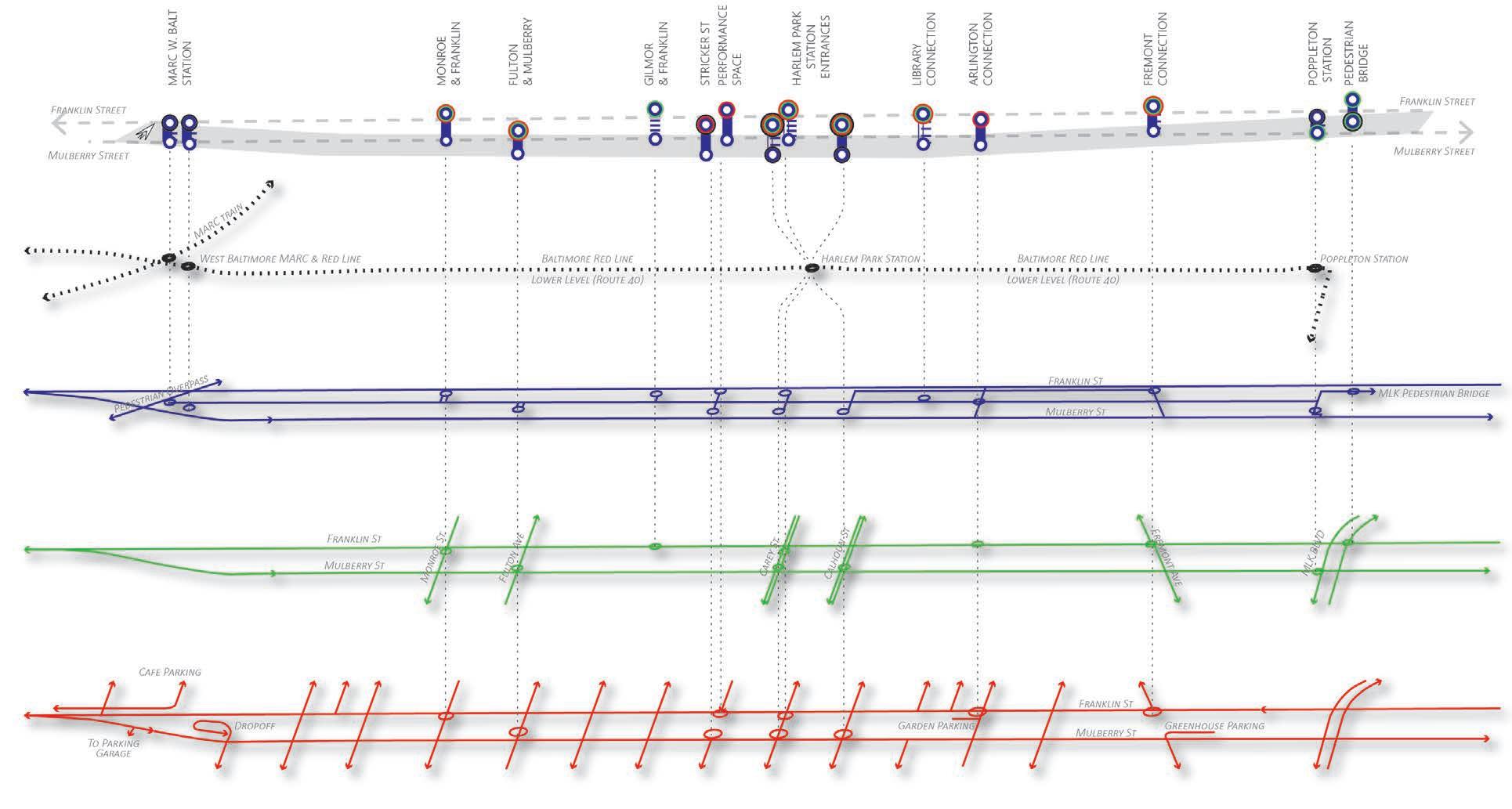

CIRCULATION AND TRANSIT CONNECTIONS DIAGRAM: ROUTE 40 ECOLOGICAL PARK

Showing proposed connections between train lines, pedestrian paths, bicycle paths, and vehicle routes.

22

AutoCAD, Adobe Illustrator

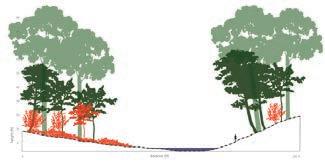

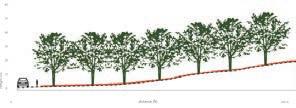

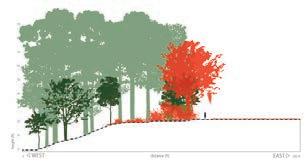

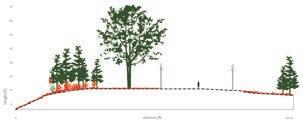

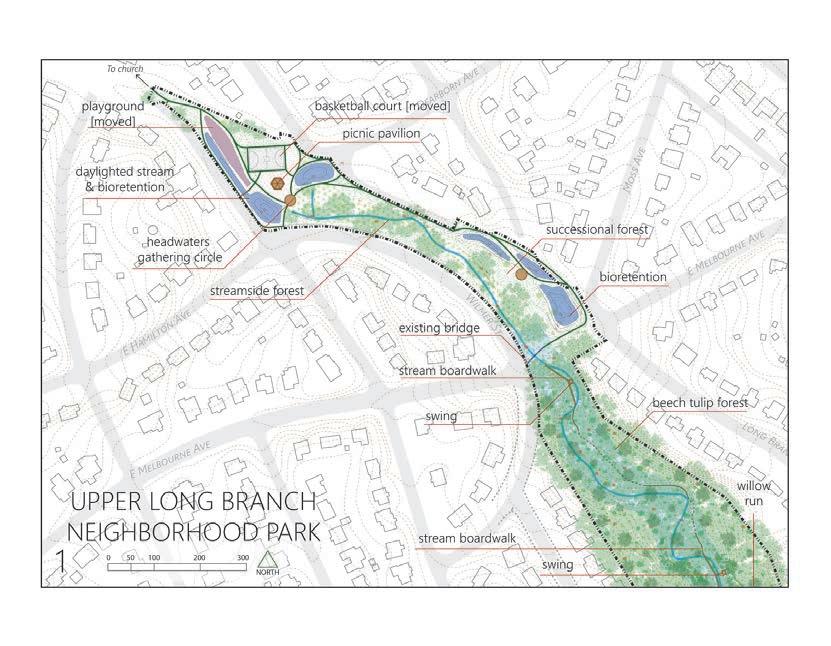

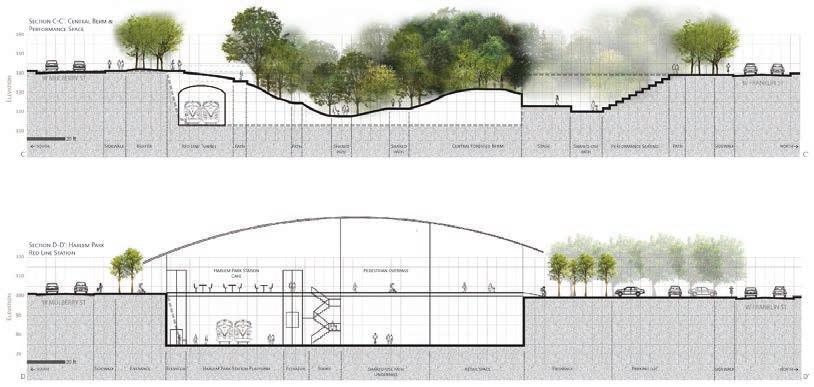

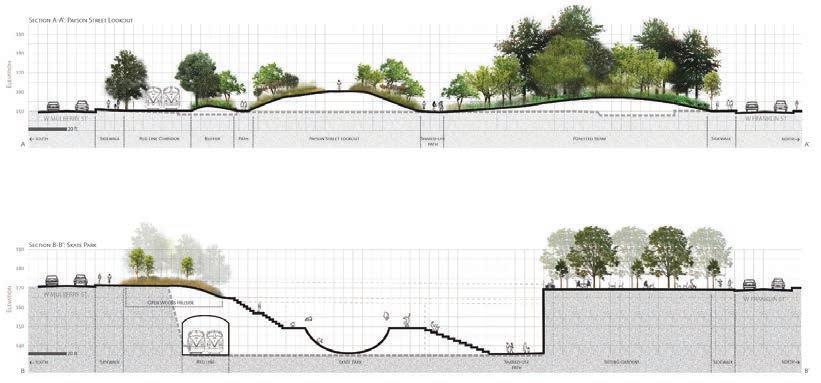

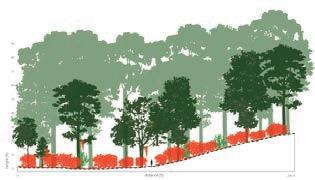

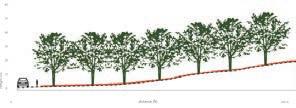

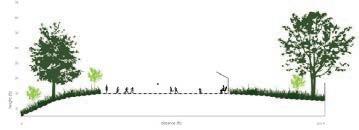

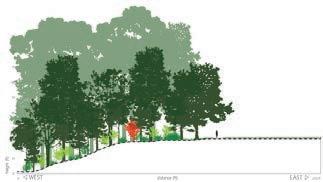

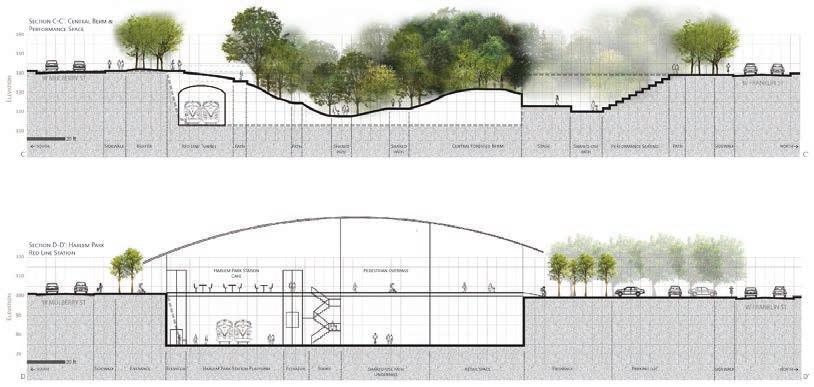

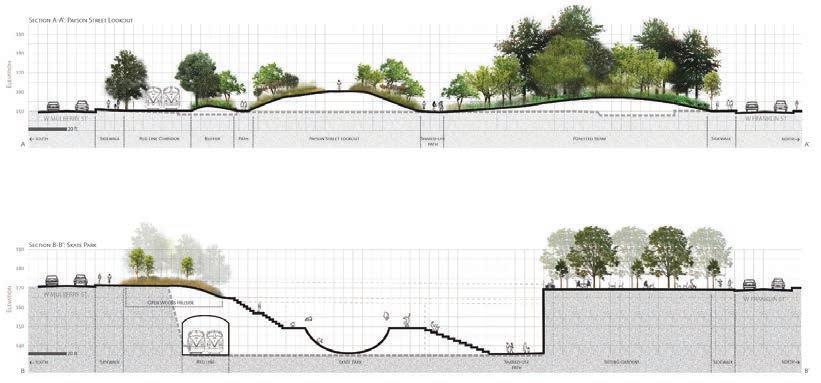

SECTIONS

The dramatic elevation changes on the current site, vestiges of the dramatic construction of the highway in the mid-1970s, provide a rich design opportunity.

LEGEND

AutoCAD, Adobe Illustrator

23

PERSPECTIVES: ROUTE 40 ECOLOGICAL PARK

24

Adobe Photoshop, SketchUp, Google Earth

25

PERSPECTIVES: ROUTE 40 ECOLOGICAL PARK

26

Adobe Photoshop, SketchUp, Google Earth

27

BALTIMORE BIODIVERSITY TOOLKIT POSTER SERIES

BUILDING BIODIVERSITY IN THE

Creating habitats on small plots - a resident’s guide to ecological planting

MID-ATLANTIC

Illustrations created by Emma Podietz, in collaboration with Dr. Lea R. Johnson of Longwood Gardens and University of Maryland, College Park, and Clare Maffei of U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and the Greater Baltimore Wilderness Coalition.

West Baltimore, Maryland

28

PROJECT TYPE:

DESCRIPTION: Interdisciplinary collaboration, Maryland ASLA Fellowship Project

This poster series is my contribution to a regional effort to build biodiversity in Baltimore, Maryland through residential-scale planting design. The posters integratbasic ecological concepts with design ideas and focus on attracting charismatic animal species.

MID-ATLANTIC ECOSYSTEMS AND ANIMAL SPECIES

You usually see butterflies our in the sun, but these distinctive swallowtails can be found wherever Pawpaws are found. Pawpaws are a fruit tree that thrives in the wetter, shady forest understory.

The Acadian Flycatcher is a perfect example of a forest interior dwelling bird. They need large tracts of mature forests to thrive.

Barred Owls’ distinctive call sounds like “Who-cooks-for-you?” These noble birds need large, dead trees for nesting sites. Usually they are found in undisturbed wooded areas, but have been seen in small patches of urban forest as well.

Milkweed-filled meadows are crucial in monarch’s famous migratory journey. They need milkweed to survive, and are increasingly threatened by habitat loss.

Find the beautiful goldfinch in low branches of shrubs, and foraging for nuts and seeds in open grassy areas. Unafraid of city life, these resident birds light up the urban landscape.

On clear summer nights, you can look for nighthawks swooping around streetlights to catch flying insects. They are fueling up for their long winter migration to Central and South America. Their name is deceiving; they have been constantly declining in population in recent years.

These beautiful birds can be found lower in the foliage than the typical warbler. Look for them foraging deep in the woods on the forest floor.

The official bird of Washington D.C., the Wood Thrush migrates to our region during the spring.

These non-aggressive native bees form individual families, as opposed to building colonies. Their fascinating life cycle depends on undisturbed hollow grasses, making them vulnerable to mowing and clearing.

Native bees are essential pollinators in local ecosystems. These non-aggressive ground nesters are threatened by habitat loss from mowing and raking.

Red-bellied Woodpeckers are fairly common, but they are a conservation priority because the holes they peck into trees provide necessary habitat for countless other small animals.

WATER’S EDGE

The beautiful luna moth is unmistakable. Its long tails and eye-like wing patterns deceive predators such as owls and bats. It relies on specific host trees, such as walnuts and sweet gums; specialists like this are especially threatened by deforestation.

RUBY-THROATED HUMMINGBIRD

This charming tiny bird can be seen drawing the nectar from red tubular flowers. It needs tons of sugar to power its long migration to the Gulf of Mexico, which it fascinatingly does often without stopping.

Perhaps the most misunderstood of local mammals, the unique Virginia opossum is North America’s only marsupial. Commonly mistaken for rodents, they actually eat rodents, along with ticks, roaches, and garden snails. Got a possum in your yard? You can’t do better.

Did you know that salamanders breathe through their skin and so it has to stay wet all the time, but it produces a chemical that protects it from fungus! Look for them under logs and rocks in woods and near water.

The caddisfly is well known as an indicator of stream health. They can not tolerate a contaminated stream. So if you see a caddisfly nearby, you know you are next to a healthy habitat. Eastern box turtles used to be a common wildlife encounter in Maryland. Due to habitat loss and increased car-related deaths, their numbers have declined dramatically. To see more box turtles, we must rebuild and protect their habitats.

These iconic birds forage for insect and ripe fruits at the very tops of trees. They like the darkest, ripest fruits. Find them on stream banks and forest edges in conservation areas, and maybe even in your own backyard.

These small herons are nocturnal, hunting in streams and tidal waters at dawn and dusk for crustaceans. Their breeding habitats are vulnerable to sea level rise, so we need to protect inland habitat for them to relocate to.

REDSHOULDERED HAWK

These beautiful hawks have seen a population rise in recent years. They are the easiest hawk to identify because of their distinctive appearance and call.

For more information about the Biodiversity Toolkit ambassador species, scan this QR code.

GOLDFINCH

COMMON NIGHTHAWK

ZEBRA SWALLOWTAIL BLACK-THROATED BLUE WARBLER

GOLDFINCH

COMMON NIGHTHAWK

ZEBRA SWALLOWTAIL BLACK-THROATED BLUE WARBLER

MONARCH BUTTERFLY ORCHARD BEE

ACADIAN FLYCATCHER BARRED OWL WOOD THRUSH

GOLDEN NORTHERN BUMBLEBEE

LUNA MOTH

RED-BELLIED WOODPECKER

BALTIMORE ORIOLE YELLOW CROWNED NIGHT HERON

BOX

TURTLE CADDISFLY

FOREST EDGE INTERIOR

RED-BACKED SALAMANDER

VIRGINIA

OPOSSUM

FOREST

Sunny, open spaces; few to no trees; grasses & wildflowers

MEADOW

Sun and shade; transition zone between open areas and forest; trees, vines, and shrubs

Running water, sun and shade, mosses, ferns, and water-loving species.

Shade, full tree canopy coverage, understory trees and forbs

OUR REGION HAS AN AMAZING VARIETY OF HABITAT TYPES, DRIVEN BY HILLY TOPOGRAHPY AND PLENTY OF RAINFALL. AS A RESULT, MANY DIFFERENT TYPES OF ANIMALS CAN FIND A HOME HERE.

29

These two posters draw heavily on the idea of the ecological niche, illustrating how that translates to the urban environment. The information here is intended to build and for people to begin to see themselves in those interactions. The concept of “focus habitats” draws a parallel between types of naturally occuring habitats and urban

YOUR YARD: A BUILDING BLOCK OF BIODIVERSITY

Iconic, migratory monarchs depend on plants in the milkweed family; these are the only plants monarch caterpillars can eat. In late spring, they lay eggs on milkweeds in the MidAtlantic.

After the last frost, queen bees emerge from hibernation under loose grasses and leaf litter, seeking a place to build a nest.

These bees emerge from hibernation in early spring, seeking pollen and nectar. They are often found in orchards because fruit trees blossom earlier than other plants.

The beautiful luna moth emerges in mid-Spring. They mate, and the adults do not eat; they immediately lay eggs on walnut, sweetgum, or hickory trees, and then die.

These charming, charismatic birds arrive in North America in Mid-May. They immediately mate and find a spot to lay and guard their eggs. They lay eggs in open, rocky areas, often in gravelly fields or on rooftops.

QUALITY HABITAT FOR LOCAL ANIMALS REQUIRES THE RIGHT CONDITIONS YEAR-ROUND. YOU CAN PROVIDE THIS WITH SOME SMALL--OR LARGE--CHANGES TO YOUR SPACE.

The conditions of your space -- such as light and soil moisture -- will determine which plants can grow, and which type of habitat you can create.

To get enough energy for the rest of their journey north, monarchs need nectar sources in early and midsummer from blooming flowers.

Queens need pollen and nectar early to feed her young. Once worker bees are born, they need pollen and nectar to expand the nests and feed future queens.

Instead of forming a nest, orchard bees form individual families. Within 5 weeks of emerging from hibernation, mothers lay their eggs individually in compartments inside hollow stems or other long, narrow holes.

Egg compartments inside of a hollow stem

In the fall, new queens fatten up on fall-blooming flowers for winter hibernation.

Once these eggs hatch, the second generation is born. This one will overwinter, and emerge in spring to start the cycle again.

In early spring, these tiny birds build cup-like nests out of fluffy grasses and spiderwebs.

North America’s only marsupial will mate any time except for winter, and their babies are so small you can fit 20 of them in a teaspoon.

For protein they eat small insects such as gnats and mosquitoes, and for sugars, they are attracted to flowers such as the Canada Lily.

On the way back from Canada, monarchs also need abundant nectar sources in early fall.

Nutritious mix of pollen and wax

While the rest of the colony dies, the new queens hibernate underneath leaf litter for the entire winter.

Larvae

Mud wall

As long as their nesting sites remain undisturbed, orchard bees spend most of their life cycle in their compartments their mothers created for them. They reemerge the following spring.

Lunas can only surive on certain types of trees. If you have a walut, sweetgum, or hickory tree, avoid raking under it to avoid damaging pupae.

Nighthawks hunt insects everywhere, powering up for their winter migration to South America. The more insects, the more nighthawks.

Towards the end of summer, hummingbirds nearly double their body weight to fuel their migration to South America, which they often do without stopping.

Babies ride in their mother’s pouch until they are big enough to ride on her back while she forages for food. In the summer, they eat common pests like ticks, mice, garden snails, and mosquitoes. Opossums often move between several different shelters to evade predators.

Choose plants that are appropriate to your space and choose how they will be arranged. You can make your space a multi-seasonal resource for biodiversity.

Intensity of color indicates the presence and visibility of a species in the Mid-Atlantic throughout its life cycle.

In the fall, they forage for fallen fruits such as pawpaws and acorns. Very vulnerable in the winter, they often hide in old squirrel holes or hollow logs. Don’t mistake these fascinating animals for rats!

You can help opossums by providing small shelters to keep warm in winter.

Once you have done the hard work, you can start seeing the results of your efforts and enjoy birds, butterflies and other animal species visiting your space.

MARAPRMAYJUNEJULYAUGSEPTOCTNOVDECJANFEB

1. OBSERVE

3. SEE WILDLIFE

2. TAKE ACTION

MONARCH BUTTERFLY Danaus plexippus GOLDEN NORTHERN BUMBLEBEE COMMON NIGHTHAWK Chordelies minor BLUE ORCHARD BEE Osmia lignaria LUNA MOTH Actias luna VIRGINIA OPOSSUM Didelphis virginiana RUBY-THROATED HUMMINGBIRD Archilochus colubris

TIME

Bombus fervidus

The migratory path of the Eastern monarch

Fall-blooming flowers provide crucial late-season nectar and pollen for bees and butterflies.

The migratory area of the common nighthawk

May & June monarch habitat: milkweeds and nectar-rich flowers

The migratory area of the ruby-throated hummingbird

Queens create nests and lay eggs in matted grasses.

Severely limiting raking and mowing helps ensure the survival of ground hibernating species.

Luna moths’ long tails create an optical illusion that decieves predators like bats and owls.

At twilight in summer, look for nighthawks swooping for flying insects beneath streetlights.

The Canada Lily is highly dependent on hummingbirds for pollination.

30

awareness and curiosity about local ecological interactions, urban conditions that provide analogous conditions.

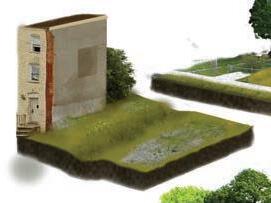

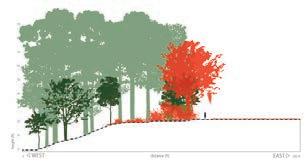

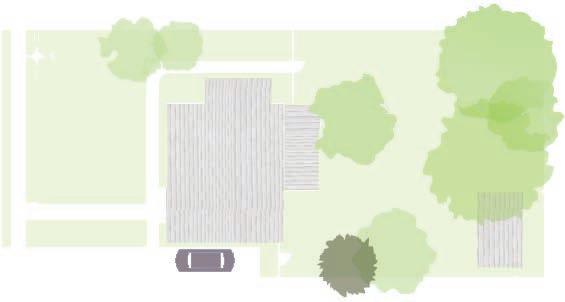

CHOOSING YOUR FOCUS HABITAT

ONCE YOU KNOW YOUR SITE CONDITIONS, YOU CAN CHOOSE WHICH ECOSYSTEM TYPE TO FOCUS ON.

If your site has few to no trees and low vegetation such as grass, you have conditions that are most akin to a meadow. This is quite common in urban environments.

Forest edges are a mixture of open, sunny areas with shaded patches of trees, shrubs, and vines.

Forest edges are common in urban environments where humans have cut through forests to construct roads and buildings.

MANY FAMILIAR URBAN SETTINGS, SUCH AS VACANT LOTS, YARDS, AND PARKS, HAVE SIMILAR CONDITIONS TO ECOSYSTEM TYPES FOUND IN THE WILD.

There are many different types of water-adjacent ecosystems in Maryland, also called riparian ecosystems. In urban areas, these are uncommon outside of conserved areas.

Dense tree canopy, shade-tolerant understory plants, low light, and high humidity characterize forest interiors.. It is now quite rare to find these conditions in urban environments.

Most of the East Coast was previously covered in forest. Many animals can only survive in these densely canopied areas.

Meadows are usually dry, but they can be wet in low spots where water concentrates.

Usually a mix of native grasses, wildflowers, and perennial plants.

These ecosystem types are not mutually exclusive; a vacant lot, for example, can have both meadow and forest edge conditions.

Even if you don’t have a stream running through your backyard, anywhere where water pools or flows has habitat potential.

WATER’S EDGE

N S EW N S EW N S EW N S EW

FRONT YARD ROW HOUSE BACK YARD ROW HOUSE BACK YARD VACANT LOT VACANT LOT NATURAL MEADOW NATURAL EDGE NATURAL STREAM NATURAL FOREST INTERIOR

BACKYARD HOME IN THE WOODS

SUBURBAN

MEADOW Sunny, open spaces; few to no trees; grasses & wildflowers FOREST EDGE Sun and shade; transition zone between open areas and forest; trees, vines, and shrubs

Running water, sun and shade, mosses, ferns, and water-loving species. INTERIOR

Shade, full tree canopy coverage, understory trees and herbs

FOREST

31

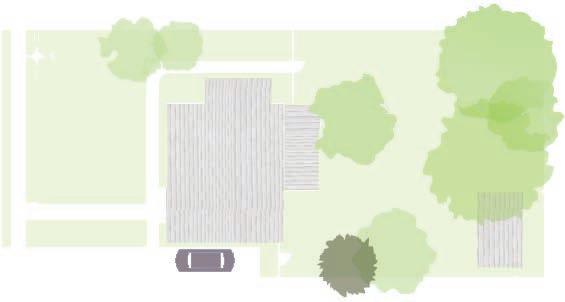

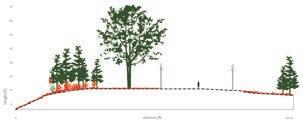

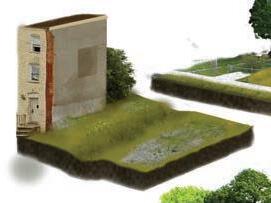

These two posters explore the practical aspects of assessing and observing land with the intention of making plant selections. The emphasis here is on matching plants of providing resources to local wildlife. The “Meadow” poster provides an example of a habitat type that can be created in many places in the urban environment: for example,

ASSESSING YOUR SPACE AND MAKING A PLAN

OBSERVING YOUR SPACE WILL HELP YOU DECIDE WHAT YOU WANT TO CHANGE, AND WHAT YOU WANT TO KEEP.

Whatever the size of the space you’re working with, you can make changes that will benefit local wildlife.

3. NEARBY WILDLIFE

Some wildlife sightings are extremely common in urban areas, such as deer, crows, starlings, and squirrels. These species have adapted well to environmental conditions in areas that have been modified by humans. Some other species may need a bit of extra help finding a comfortable home in urban settings, and that’s where you come in.

To understand lighting on your site, you first need to know which way is North, South, East, and West in relation to your house. In the Northern Hemisphere, south-facing surfaces get the most sunlight, because of the sun’s angle in relation to the Earth. This will greatly affect your planting choices.

1. LIGHT CONDITIONS

CREATE A BASEMAP

Measure the approximate boundaries of your space, and draw a birds-eye view map. Note the location of grassy areas, trees, pavement, and buildings. It does not have to be perfect. Try finding your house on a mapping app and drawing what you see.

4. WATER MOVEMENT

Try taking a photo of your space at various times on a sunny day to get an idea of how much light each area gets. Identify areas that are full sun (6+ hours of direct sunlight per day), part shade (between 3-6 hours), and full shade (less than 3 hours).

2. EXISTING PLANTS

Notice which plants you’d like to keep, and which you’d like to replace.

You don’t have to start over completely-- you may already have more animal and plant diversity in your space than you suspect.

It is important to distinguish between native plants and non-native plants. Native plants provide more resources to native animals than non-native plants do, because they share an evolutionary relationship.

DOCUMENT YOUR OBSERVATIONS

Combine your observations of water, light, plants, and animals and write them as notes on your basemap. This will help you make decisions later.

The next time it rains, observe where water is flowing and pooling around your land. Does it drain to the street? Are there any wet spots where water tends to collect? Does water come in from neighboring properties or flow off of your roof? Water availability will determine which types of plants you can plant.

N S EW

BACK YARD N S EW EW EW EW EASTsunrise WESTsunset 6:00 AM Full shade Full sun Part shade 6:00AM 12:00 PM 12:00 PM 6:00 PM 6:00PM

FRONT YARD

N S EW FRONT YARD FRONT YARD BACK YARD BACK YARD water

to

water flows to street water flows off rooftops water flows off rooftops water pools in

water pools in yard some

N S EW Grass lawnArborvitaePin oakWhite oaks Pin oak Sweetgum Rhododendron Dogwood N S EW sweetgum tree oak tree Group of oak trees ornamental evergreen WET SPOT WET SPOT dry and sunny; grass suffering dogwood tree unknown shrub DRIVEWAY MAIN HOUSE EAST WEST FRONT YARD BACK YARD WET SPOT DRY + SUNNY PART SHADE LEGEND N S EW

flows

street

yard

infiltrateswaterinto soil

White-throated sparrow Monarch butterfly Virginia opossum Common nighthawk Northern cardinal Common crow European starling White-tailed deer Noticing local wildlife populations makes you more aware of ecological interactions in the landscapes that surround you.

YOUR HOUSE: THE STARTING POINT

FRONT YARD DRIVEWAY SIDE PATH BACK YARD SHED MAIN HOUSE SIDEWALK rain water flows down into street intenseafternoonsun FRONT WALK STREET SHED

MEASURE THE BOUNDARIES OF YOUR SPACE. OBSERVE WATER, LIGHT, PLANTS, AND ANIMALS. g

32

to their optimal growing conditions, and also with the aim example, in sunny yards and vacant lots.

MEADOW FOCUS HABITAT:

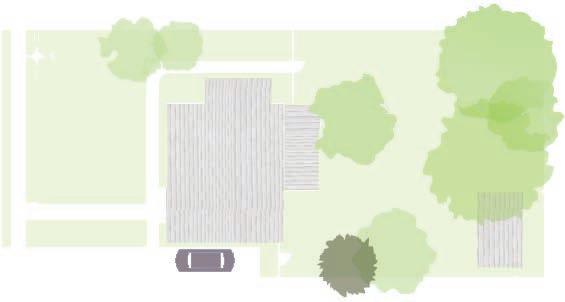

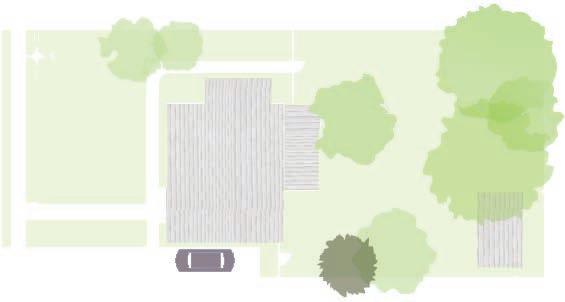

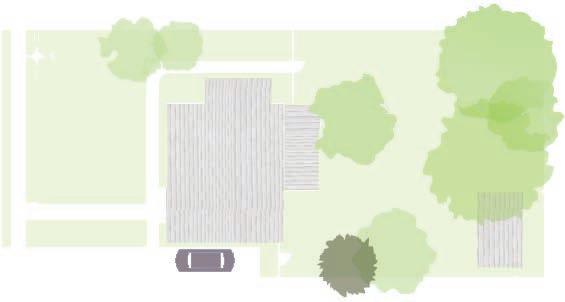

SAMPLE PLAN: STANDALONE HOUSE

FRUIT-BEARING SHRUBS

Benefits: Pollen/Nectar in spring; nutritious fruit in summer; deer-resistant

Species: Black raspberry (Rubus alleghensis) & Lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum)

HARDY QUICK-GROWERS & GROUND COVER

Benefits: A fast-growing perennial, combined with a round cover, prevents weed colonization; garden edges appear full

Species: Mountain mint (Pycnanthemum muticum), Golden ragwort (Packea aurea)

MILKWEED HIGHWAYS

Benefits: Pollen & nectar in summer; deer-deterrent; monarch breeding habitat. Plant near edges and in large swaths.

Species: Butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa), Common milkweed (A. syriaca)

GRASS SUBSTITUTE: MEADOW SEED MIX

Benefits: Meadow seed mixes typically contain a mix of native grasses, perennials, and annual species, providing diverse habitat and nutrition sources.

SUNNY; OPEN; FEW TO NO TREES; GRASSES & WILDFLOWERS

SPRING

SUMMER WINTER FALL

YOUR HOUSE FRONT YARD

common nighthawk monarch butterfly v irginia opossum

Spring wildflowers attract insects they eat Monarch caterpillars can only eat milkweed.

Low grassy areas provide nesting habitat On their way up the coast, monarchs lay eggs on milkweed leaves in springtime.

FOOTPATH BRUSH PILES & BIRD HOUSES

Leaving brush piles adds essential habitat for ground-nesters and stem-nesters of all types. Bird feeders provide a protein source for birds.

Adding a footpath through your meadow will ease maintenance.

ESSENTIALS FOR MEADOW HABITAT CREATION

1. BASIC MEADOW COMPOSITION

Meadows are usually planted with about 50% native grasses and 50% native perennials and annuals.

SAMPLE PLAN: ROW HOUSE

WINTER MIGRATION TO SOUTH AMERICA

Summer flowers attract insects they eat

Wildflowers and milkweeds provide nectar sources when butterflies emerge Monarchs create chrysalis on low stalks and branches

On their way south from, fall-blooming flowers provide additional pollen and nectar for the journey. WINTER MIGRATION TO MEXICO

Meadows are a temporary ecosystem in Maryland, caused by forests being cleared by human or natural disturbance. They take a bit of management and take some time to establish, but can be incredibly rewarding in their beauty and biodiversity value.

2. SEASONAL VARIETY: FLOWERS, SEEDS, FRUITS

To maximize animal biodiversity, it is important to have a variety of plants that will produce nectar, pollen, seeds, or fruits throughout the year.

3. LEAVE THE LEAVES (AND BRUSH)

Leaving fallen leaves, dead stems, and brush piles provides habitat for overwintering and ground nesting animals.

4. MILKWEED MULTI-FUNCTIONALITY

Milkweed not only attracts monarchs, but also provides nectar, pollen, and shelter for a wide variety of other animals.

neighboring back yard

YOUR HOUSE BACK YARD

Spring wildflowers provide the nectar that queens need for nest-building energy.

When eggs hatch, nearby nectar and pollen sources are needed to keep the queens going and nest alive.

FRUIT-BEARING SHRUB MEADOW SEED MIX BRUSH PILES & BIRD HOUSES MILKWEED HIGHWAYS

Queen bees emerge in spring and create new nests in thatchy grasses.

Predominantly seed-eaters, goldfinches are attracted to bird feeders in spring.

Meadow grass seeds and bird feeders can provide constant nutrition.

They nest in low branches of shrubs and trees in the late summertime.

In the fall, new queen bees must fatten up on pollen before hibernating in the winter

As meadow plants produce more seeds in fall, goldfinches will forage for them.

In the summer, they eat ticks, mice, rats, garden snails, and other common pests.

In the summer, they eat ticks, mice, rats, garden snails, and other common pests.

They

In the fall, they forage for seeds, fallen fruits, acorns, and small mammals like mice.

continue to forage throughout the winter season.

g o

They

avoid

As

colder,

to stay in. They

in

quite vulnerable to cold. Queen

shelter. Opossums

Meadow grass seeds and bird feeders can provide constant nutrition.

ldenbumblebee american goldfinch Omnivorous opossums will forage for food anywhere.

tend to move around to different sorts of shelters to

predators.

the weather gets

they must find more shelters

especially need shelter

winter; they are

bees overwinter underneath leaf litter, thatchy grasses and other sources of

breed whenever it starts to get warmer. They find shelter in tight spaces such as wood piles, underneath shrubs, and in burrow holes left by other animals

FOOD SHELTER MIGRATION

33

emmapodietz@gmail.com 215-518-7219

SketchUp, Adobe Photoshop

SketchUp, Adobe Photoshop

Map credit: Kirk Gordon, Centro Geografico Augustin Codazzi

Map credit: Kirk Gordon, Centro Geografico Augustin Codazzi

Rio Claro may have been part of the Dotted area No. 2: Nechi Pleistocene refuge. From Haffer (1969)

Rio Claro may have been part of the Dotted area No. 2: Nechi Pleistocene refuge. From Haffer (1969)

ArcGIS, Google Earth, Adobe Illustrator

ArcGIS, Google Earth, Adobe Illustrator

GOLDFINCH

COMMON NIGHTHAWK

ZEBRA SWALLOWTAIL BLACK-THROATED BLUE WARBLER

GOLDFINCH

COMMON NIGHTHAWK

ZEBRA SWALLOWTAIL BLACK-THROATED BLUE WARBLER

In the summer, they eat ticks, mice, rats, garden snails, and other common pests.

In the summer, they eat ticks, mice, rats, garden snails, and other common pests.