9 minute read

Leading in Ethiopia

Leading for CHANGE By Kerry Ludlam

Even over the phone, Lemlem Beza’s intensity comes through clearly. She’s a student, a scientist, a leader, a mother—all at the same time—and you wonder how she manages it. Then, as the conversation progresses, you realize that heartbreak can be a powerful motivator—something Beza knows well. “My elder sister bled to death after giving birth,” Beza says. “That moment made me decide that I was going to work in the medical field to help my family and my country.” Beza was in eighth grade when her sister died. One of 17 siblings, she grew up in Fiche, a remote central Ethiopian village 120 kilometers from Addis Ababa, where she now lives.

Now a nurse clinician in the emergency department at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital (TASH) in Addis Ababa, Beza also mentors and teaches postgraduate students at the bedside. She spends two days of the workweek performing her clinical duties and teaches one day a week. She reserves the remaining two days for her work in the Emory-Addis Ababa University (AAU) PhD in Nursing Program.

“I have a hectic and crowded schedule, but that is what it takes at this point,” she says.

Ethiopia's storied monument to the Lion of Judah stands a few blocks from TikurAnbessa Specialized Hospital in downtown Addis Ababa.

sustainable partnership

Over a decade ago, Professor Lynn Sibley RN CNM PhD received a $5 million grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to improve maternal and infant health in Ethiopia. At the same time, she was laying the groundwork for Emory-Ethiopia, a partnership that would bring Ethiopia its first nursing PhD program and launch an initiative to transform nursing practice in Ethiopia.

Since 2010, Emory nursing faculty and students have partnered with leaders, health workers, and community members in Ethiopia to implement and educate people on simple, low-cost solutions that can be used in any environment to improve maternal and infant health in Ethiopia. One example is Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC), which is the basic act of holding an infant in constant skin-to-skin contact during the first days of life. While it typically involves exclusive breastfeeding, any parent or guardian can provide KMC.

“We have 35 years of science to show that KMC is effective in improving survival for low-birth-weight infants,” says Professor John Cranmer DNP MPH MSN ANP-BC, principal investigator for the KMC study. “It’s inexpensive and easy, but across the globe, it’s used with fewer than five percent of babies because people just don’t know about it. We’re working for it to become the standard of care for babies who need it.”

The partnerships and trust built between NHWSN faculty and staff and their local counterparts that started with Sibley’s work in Ethiopia have been fundamental in launching the broader Emory-Ethiopia Initiative. They have allowed for other projects to evolve, including the Emory-AAU PhD in Nursing Program and student-led regulatory changes to the nursing profession.

“The sustained partnership in Ethiopia is critical,” Cranmer says. “There is mutual trust and recognition of what each partner brings to the partnership to create meaningful discovery and science.”

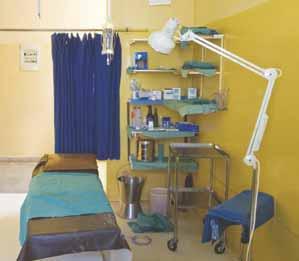

A hallway at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital in Addis Ababa

Beza at hospital with Professor Philip Davis DNP MBA ANP-BC

the need

Beza’s father, who had diabetes, passed away after an endocrine emergency. She believes he might have survived with adequate care.

“I grew up in a remote village where there is almost no health service,” Beza explains. “Health coverage is inadequate, and people are suffering. As an emergency professional, I have witnessed patients come to our emergency room with many complications, resulting in preventable deaths.”

Experiences like Beza’s are not uncommon in Ethiopia. Its health system struggles with maternal and infant mortality, a longer-living population with an increasing chronic disease burden, and infectious diseases, among others.

Adding to Ethiopia’s health care challenges is the lack of qualified medical professionals.

There is less than one medical professional per 1,000 people, far lower than the World Health Organization’s recommended minimum of 4.45 per 1,000. Most physicians work in private practice in larger cities. As for more remote regions, there are no physicians.

“In rural Ethiopia, nurses are critical to providing care, but there still aren’t enough of them,” explains Martha Rogers MD FAAP, director, Lillian Carter Center for Global Health & Social Responsibility and principal investigator of the African Health Workforce Project. “There are health extension workers, which are community-based health workers, but they are not a substitute for qualified nurses. Think about what can happen when there are no nurses to provide vaccines and engage in early child health care.”

Beza and her extended family celebrate her mother’s birthday Beza during her Emory visit last year.

the solution

Lynn Sibley RN CNM PhD, a trusted colleague at both Emory and AAU with a history of work in Ethiopia, assembled a team in both Ethiopia and the United States to develop the Emory-AAU PhD in Nursing Program. One of Sibley’s research collaborators, Abebe Gebremariam MD, helped the group navigate AAU’s governance structure and make connections with key contacts in Ethiopia. Gebremariam is now Emory’s in-country coordinator for Ethiopia.

With a focus on technology, the program offers a hybrid inperson and distance-learning curriculum. Students attend some courses at AAU and use tools like an interactive smart classroom to participate in NHWSN courses in real-time alongside NHWSN students. This use of high-tech teaching methods, combined with small class sizes, means students can connect and learn from each other despite the distance.

The Emory-AAU PhD course of studies relies heavily on mentorship, as well. “It is incredibly meaningful to mentor these students along the continuum from student to scientist,” says Rebecca Gary RN PhD FAHA FAAN, director of the Emory-AAU PhD in Nursing Program. “They’re very motivated, and mentors work with them on writing skills, dissertation development, and research methodology, among other things that will help them become nurse scientists and leaders.”

Beza, who is mentored by Gary, completed her intensive at Emory in the spring of 2019.

“My stay in Atlanta was wonderful because I could focus on my dissertation proposal work,” Beza says. “I collaborated with my advisor in person, spoke with her at length, and got her support and advice. I got to know many people that I can consult and work with in the future.” The intensive also provided opportunities for training in citation management, statistical software, and literature review. Of her time at Emory, Beza notes that it was hard work—but there was time to socialize, too.

“I had lots of fun and a great cultural exchange with my classmates and others,” Beza says.

The highlight?

“After a lot of work, I successfully defended my proposal,” Beza says.

Mentors work with students to make post-graduation plans, including post-doctoral fellowships or faculty opportunities. The hope is that these students will be a force for change—transforming the Ethiopian health system and increasing health coverage for all Ethiopians.

Currently, 11 students are enrolled, five have defended their proposals successfully, and one has graduated. That honor goes to Fekadu Aga, MSN, who graduated in 2019 and is now a Fogarty Global Health Post-Doctoral Fellow. Beza has also been awarded a Fogarty Global Health Post-Doctoral Fellowship with which she will examine community education interventions, risk reductions, and screenings for acute coronary syndrome.

emory nursing in ethiopia

Launched in 2015, the Emory-AAU PhD in Nursing Program is a collaboration between Emory School of Nursing and AAU. It is the first nursing PhD program in Ethiopia and the only one of its kind in Africa.

As part of the larger Emory-Ethiopia Initiative, the Emory-AAU PhD in Nursing Program has goals well beyond the education of individual nursing students. The program also aims to create a qualified, motivated workforce of nurse scientists, educators, and national nursing leaders in Ethiopia. These trailblazers will sustain the program by becoming AAU leadership and faculty, while also working to bolster access to health coverage throughout Ethiopia.

The only woman from her family to have attended college, Beza will finish her PhD in late 2020, a crowning achievement after years of work. She earned her diploma in nursing from the Asella School of Nursing. Beza also has her bachelor of science degree in clinical nursing, her master’s of science in emergency medicine and critical care, as well as her nurse practitioner degree from AAU's School of Nursing and School of Medicine.

lasting change

While Beza is eager to complete her PhD, receiving her doctorate is only one step in her plan to change how health care is taught and delivered in Ethiopia. In addition to her studies and clinical work, she is also leading the charge to eliminate—or at least ease—many of the challenges nurses face in Ethiopia.

“Because there’s no standardization of the nursing curriculum, anyone can call themselves a nurse, or teach nursing,” Beza says. Additionally, physicians often decide what role nurses play in their practices or hospitals, so there is little consistency in different parts of the country.

“Currently, there is only one regulatory body for all medical professionals in Ethiopia, and it is very loose in scope and fragmented,” Beza says. “It’s important for nurses to have our own governing entity in place to both ensure quality of practice and delineate professional standards and day-to-day protections on the job.”

Fortunately, she’s not working alone. Beza has formed a task force of six, which includes a government leader from Ethiopia’s Ministry of Health, Linda A. McCauley PhD RN FAAN FAAOHN, dean and professor at Emory’s School of Nursing, and Rogers, to form a nursing regulatory body in Ethiopia and develop standards of care and practice. With the task force’s support, Beza is advocating for national reform, including the development of a national nursing council to set standards for training, licensure, and continuous professional education.

With the support of Rogers, Beza has leveraged connections to form a South-to-South collaboration between Ethiopia and Kenya, which already has a strong health workforce regulatory system in place. Having a PhD will “Lemlem developed the for making lay the groundwork change. plan, and I just helped make the connections,” Rogers explains. “It is a smart strategy because it’s costeffective, any travel is just next door, and nurses in Ethiopia and Kenya are operating in a similar environment. They’re much more alike than different, and what worked for Kenya might very well work for Ethiopia in terms of putting a regulatory structure in place.”

Beza, along with the task force, visited Kenya in March 2020 to meet with regulatory boards, tour facilities, confer with Kenyan nurse leaders, and share ideas for how to implement regulatory practices in Ethiopia. Gary says that Beza’s work through the EmoryAAU PhD in Nursing Program gives her an advantage as she works to effect change.

“By virtue of having a PhD, she is prepared to sit at the table with other leaders and negotiate,” Gary says. “She has worked to elevate her own status so that she can make systemic change.”

For Beza, the Emory-AAU PhD in Nursing Program has uniquely prepared her for leading the task of transforming nursing and health coverage in Ethiopia.

“Having the chance to be part of Emory and see how nursing has its own scope of practice and regulatory body has shown me how I can change the system and do my part,” Beza says. “Having a PhD will lay the groundwork for making change. As I move forward in both my daily life and work, and in my collaboration with the task force, I’m empowered and confident.”