6 minute read

Finding Aloha on Molokai

from Bon Vivant Fall 2019

by Ensemble

FINDING ALOHA ON MOLOKAI

This Hawaiian island embodies the true sense of the destination’s spirit – love, friendship & responsibility

BY LIZ FLEMING

BIGGEST ISN’T ALWAYS BEST – PARTICULARLY in thetravel world. Book a trip to the tiny island of Molokai and you’ll soon discover everything you always dreamed Hawaii was, but could never find on the other islands. Indeed, this place is the real Hawaiian deal.

Fifth largest of the islands, Molokai is just 60 kilometres long and 16 kilometres wide, and it doesn’t have a single skyscraper or shopping mall. In fact, you can drive all over the island without ever finding so much as a traffic light.

Kalaupapa National Historical Park on the island of Molokai

Seven small hotels offer 140 rooms – that’s it – and in most of them, your wake-up call will be the sound of a rooster crowing under your porch. Don’t look for glitzy beach bars, five-for-ten-dollars t-shirt shops or casinos. You won’t find a single one.

What you will find are roughly 7,400 proud, friendly people ready to tell you that they’re true Hawaiians. According to state statistics, more people on Molokai have Hawaiian blood than on any other island, but it’s more than genetics that gives this island its authentic feel.

It’s all about an attitude of simplicity and a dedication to maintaining the Hawaiian way of life – of living aloha. "Aloha" is the first word you’ll learn on any of the islands and you’ll instantly find yourself using it as your standard hello and goodbye. But the word – particularly on Molokai – means far more.

Kalaupapa National Historical Park on the island of Molokai

"Aloha" translates to: ‘al’ – face-to-face, and ‘ha’ – the breath of life. In its fullest interpretation, aloha means love, friendship and responsibility, extended not just to your fellow human beings but also to the earth. The Hawaiian Islands are the most isolated population on the planet, widely separated from their nearest neighbours – Japan by nearly 6,500 kilometres and California, by 3,800 kilometres. In order to survive, they foster harmony and preserve their natural resources.

The Hawaiian “Aloha Spirit” law was officially enacted in 1986 and it’s taken very seriously. Aloha is both a state of mind and a way of life – it’s the essence of Molokai.

You’ll feel it when you meet Anakala Pilipo Solatorio, the last survivor of a 1946 tsunami that virtually turned Molokai upside down, sweeping through beaches, rocks, trees, homes and anything else in its path. Perhaps because he survived when so many others did not, Anakala feels he was chosen to be the protector and the keeper of traditions in his lifelong home – the beautiful, isolated Halawa Valley.

As you walk down the narrow pathway through the lush green fronds and grasses to his home, Anakala blows his conch shell to welcome you. He stands solemnly, encouraging you to come close and to lean towards him until your foreheads touch. “Now,” he says, “we will share the ‘ha’…the breath of life.”

Molokai sea cliffs

I feel unsure as I place my forehead against that of a relative stranger and even odder to breathe deliberately into his face and inhale his breath – but the practice is strangely calming and welcoming.

Together, we sit on his palapa-covered porch and Anakala tells us his stories of the valley, the tsunami, his family and his belief in the Hawaiian way of life as he knows it. As we listen to his soft voice and look at his treasured collection of handmade leis, newspaper clippings from 1946, family photos and more, we begin to relax – perhaps like never before.

In the background, the sound of a waterfall adds to the ambiance and we feel as if we’re now understanding aloha a little better. One of the stories Anakala shares didn’t take place in his valley, but rather miles away at the base of the cliffs at Kalaupapa.

There, in 1866, the first Hawaiian victims of Hansen’s disease (then called leprosy) were shipped by government health officials to quarantine them from the rest of the islands. Cut off on three sides by ocean and on the fourth, by 488-metre sea cliffs, Kalaupapa became first, their prison and ultimately, their home.

Veiw of Molokai beach

As Anakala describes it, having a family member stricken with leprosy created both fear and loathing. People desperately tried to hide ailing relatives, but ultimately, the government inspectors would come knocking.

Being exiled to Kalaupapa meant never again seeing your family, friends or home but strangely, the story was less tragic than you might expect. A visit to the museum that commemorates the Kalaupapa colony showed that a town was built, marriages happened, children were born and new families were created.

There were dances, parties, celebrations and a sense of real community in a place where there might only have been death and despair. In 1969, the mandatory quarantine order was lifted, but many residents refused to leave, choosing instead to stay where they had made their lives. There are still a handful of people living there, in what is now Kalaupapa National Historical Park, and they plan to remain.

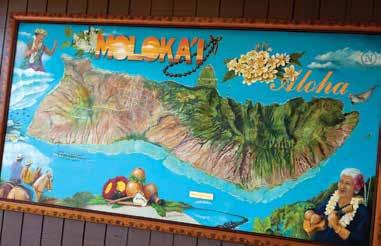

Molokai map at Kaunakakai Airport

We have to see it for ourselves and so, after leaving Anakala in his beautiful valley, we drive to the cliffs overlooking Kalaupapa. Below us, the ocean that surrounds the settlement is a brilliant cobalt blue, the sun is warm on our backs and a soft breeze plays with our hair.

Though we realize that the Kalaupapa residents may have chosen to stay because the ravages of their disease made integration into a larger society uncomfortable, we also wonder if they weren’t simply unwilling to leave the pristine retreat the colony had become – a place of quiet, of sunshine, of waves and of acceptance.

Perhaps they’d created their own version of the aloha way. Everywhere we turn on Molokai, we find that spirit alive and well. When we mention how much we’d like to get out on the water, for instance, our guide quickly arranges for us to join the Wa’akapaemua Canoe Club members for an early morning paddle.

Hawaii Tourism Authority / Tor Johnson, Dana Edmunds

No matter that they have regular teams and ordinarily no empty seats – they happily fit us in, teach us to stroke in cadence with them and take us out in their enormous canoes to see giant sea turtles hovering just below the waves. We turn out to be terrible paddlers, but the Canoe Club members graciously ignore our splashing and lilydipping.

It’s all good…all aloha. Though we eat wonderful, freshly caught fish most nights in Molokai, our sweetest food memory – and indeed, one of our happiest aloha moments – has nothing to do with healthy dining. Because Molokai has no movie theatres, no wild dance clubs and no shopping centres, we’d been thinking that our evenings would be pretty quiet.

But that was before we’d been introduced to the Kanemitsu Bakery in the small – and really, the only town of any size – Kaunakakai. One night after dinner, we join the lineup at the bakery’s back window, and stand drinking in the aroma. Soon, we’re handed the Kanemitsu special – a large loaf of what the chalkboard menu on the wall calls ‘hot bread,’ slathered in your choice of cream cheese, jam, cinnamon, butter or all of the above.

Kalaupapa Cemetary, St. Philomena Catholic Church

Yes, it’s a whole loaf and no, you don’t share. Instead, you join all your new Molokaian friends in the middle of the street and you wolf down as much of that loaf as you can. Leftovers? Guard them jealously until morning – they make an incredible, carb-laden breakfast.

Taste, they tell us, is the sense with the power to generate the most meaningful memories. If so, then I’m sure from now on, every time I smell bread baking, I’ll be transported back to that small town in Molokai, where the sweet, simple loaves eaten on a small town street corner were all we needed to make our night.

Perhaps that’s another essence of aloha – the ability to savour and share life’s simplest pleasures.