15 minute read

FINDING THE RIGHT BIT

Finding the bit that fits

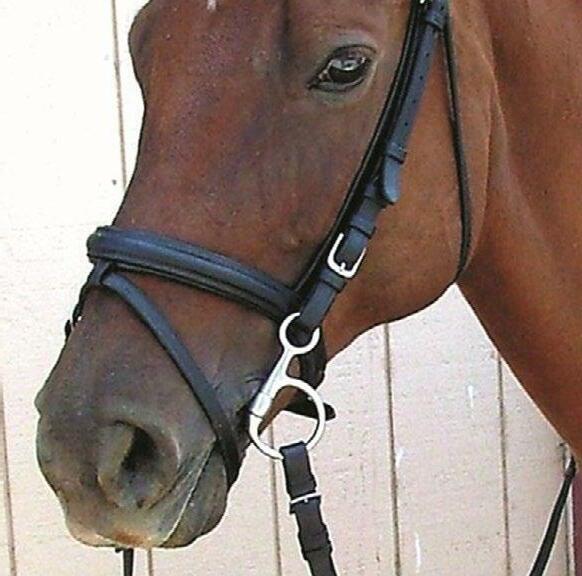

Should you use an eggbutt or a loose ring, an s-shank or a weymouth? Or, perhaps a pelham might be the answer for your particular horse. Choosing a bit can be just a little bit tricky, as DANNII CUNNANE explains.

We all want to meet our horse’s various needs in the very best way we can, and that makes falling down a bit-shaped rabbit hole all too easy. There’s an absolute smorgasbord of different bits on the market, and between them they appear to offer a solution to every conceivable problem. But which bit is really best? While it’s down to your personal preference, your discipline, and what works most effectively with your horse, we thought a run-down on what some commonly used English and western bits are designed to achieve might be helpful.

Firstly, what does a bit actually do?

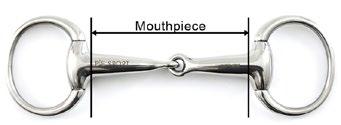

One of the most important lines of communication you have with your horse, a bit is a combination of two elements: the piece that goes inside the horse’s mouth and sits over the tongue, not surprisingly known as the mouthpiece, and the rings to which the bridle and reins attach. All bits, acting in combination with whatever bridle you use, create pressure and leverage on different parts of the horse’s mouth and head. A major point to consider when choosing a bit is the size of your horse’s mouth. In Australia we have tended to conform to three main sizes of bits, pony, cob and full. Although this is gradually changing, in Europe bits are available with variations of as little as a centimetre. Some horses and ponies fall awkwardly between bit sizes, and getting one that fits properly can make all the difference to how they respond to aids.

Different materials produce different results

A variety of substances are used to make bit mouthpieces, including both metal and synthetic materials. These can determine how much a horse salivates and therefore tolerates a bit. It’s thought that a horse with a moist mouth is more relaxed and responsive than one whose mouth is dry. B C

D

E F

G

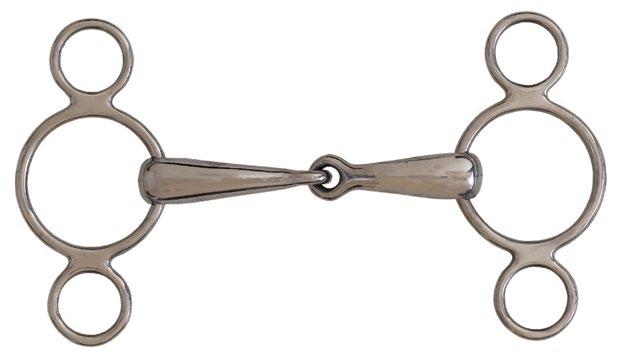

A: D-ring snaffle B: Weymouth C:Tom Thumb snaffle D: Loose ring snaffle E: Mullen mouth Pelham F: S-shank with copper bars G: French link baucher

Commonly used metals in bit manufacturing include stainless steel and nickel alloys, which generally do not rust and have a neutral effect on salivation. Sweet iron and copper tend to encourage salivation, while aluminium can be drying and is not very durable - and therefore probably not a wise choice. Synthetic mouthpieces are sometimes reinforced with an internal metal cable or bar, and rubber bits are generally thicker than the metal equivalent. Plastic coated bits usually compare in size with their metal counterparts, and some are flavoured to stimulate the mouth and encourage gentle chewing and saliva production.

The configuration of a bit determines the effect it has when pressure is applied through the reins. For example, a singlejointed bit has an action similar to a nutcracker, while the double-jointed French link lies flatter on the tongue, thus reducing the nutcracker-like effect. In contrast, the mullen mouth has no joint, is slightly curved to accommodate the tongue, and is generally considered to be milder than jointed bits.

But which bit is right for my horse?

When trying to decide which bit is best suited to your horse, consider the points of control on the horse’s head - which include the corners of the mouth, the curb groove, the bars, the palate and the poll - and what effect the action of a particular bit is likely to have on those points.

Given that the palate is the most sensitive of these, a good place to start is by looking at your horse’s mouth. Gently lift their lips to check the space between the upper and lower jaw, as well as the thickness of their tongue. A big horse doesn’t necessarily have a big mouth! In fact, you’ll discover that once you take the tongue into consideration, a horse’s oral cavity often doesn’t afford a lot of room for a bit.

Some experts recommend that you test the size of the space by carefully inserting two fingers into the mouth at the point where the bit lies. A tight fit indicates that the gap between the upper and lower jawbone is small and in order for your horse to be comfortable, bits with thick mouthpieces are probably best avoided. Additionally, horses that have a flat rather than arched palate are likely to have difficulties with a singlejointed bit because there’s little room to accommodate the nutcracker action of the joint.

And here’s another point to ponder: if you compete, is the type of bit you’re considering ‘legal’ for your discipline? Read the rules to ensure that you don’t get caught out with the wrong bit - pleading ignorance is not an excuse.

Clearly choosing a bit isn’t as simple as it sounds – so if you’re still in doubt, consult your vet, equine dentist, or another expert before making a purchase

Loose ring snaffle Getting down to bit basics

Let’s get down to specifics. First, we’ll look at some of the more popular English bits and then move on to western styles:

EGGBUTT: The eggbutt was named for its slightly oval, egg shaped cheek rings that ‘butt’ hard up to the mouthpiece. This is a fixed cheek bit, meaning that the cheek and the mouthpiece are firmly attached to one another, preventing rotation or any other movement. The advantage of this feature is that the bit sits more steadily in the horse’s mouth, which is particularly useful when the rider is a novice as the mouth is protected from much of the potential jolting that unsteady hands and/or seat can cause.

LOOSE RING: In a loose ring bit, the rings run through holes at either end of the mouthpiece and can rotate freely. This equates to more movement in the mouth which has the potential to be distracting, so this is probably not a good choice for a horse that is either inexperienced or hesitant when it comes

to establishing steady and consistent contact with your hands. Similarly, if you know your hands tend to be a little over-active, a fixed ring bit may well be a better option.

FULL CHEEK: Full cheek snaffles are a useful choice for green or young horses. The full length shanks add positive reinforcement by pressing against the horse’s cheeks when asking it to turn. They also help to prevent the bit from being dragged through the mouth. Using keepers (also known as fulmer loops) on the bridle help to keep the shanks in the correct vertical position, but care should be taken that they don’t overly alter the angle of the bit.

BAUCHER: This bit features a ‘hanging’ cheek piece: bars extend up from the eggbutt style rings, and the reins are attached to the lower bit ring. The baucher cheeks offer stability for the mouthpiece that is thought to be even greater than that of the eggbutt. It has also been suggested that the bit’s design creates extra leverage, which allows for additional pressure to be placed on the poll. However, many experts believe that in reality, this is unlikely to be the case.

GAG: This bit is designed to allow the bridle cheek pieces and reins to attach to different rings. This creates leverage, the severity of which depends upon where the reins are attached. A gag bit works on the horse’s lips and poll simultaneously, with the pressure on the lips raising the horse’s head. The gag can be useful with a horse that pulls, tends to travel with his nose to the ground, leans on the bit, or has a propensity to bolt. Because the gag is quite severe, it should only be used by an experienced rider with an independent seat and hands. The benefit of a gag bit can be that because it creates extra braking, it can be used gently in order to be effective, so a horse that might need a lot of pressure in a mild bit, will only need a little pressure in a gag bit. Often a horse

Erreplus JD Jump (with SL) 17” $4,500

Erreplus Elena 17” $4,250

For more information visit:

equestrianhub.com.au

Erreplus Adelinde 17” $3,900 $3,500

H

I

J

H: Correction bit I: The Baucher snaffle J: Ported barrel Kimblewick

that learns to travel softly in a gag, can gradually revert back to a milder bit.

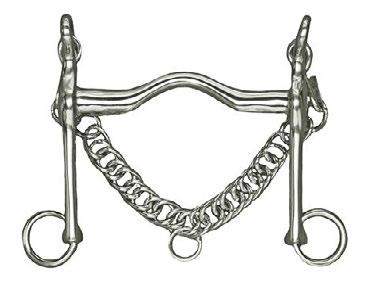

PELHAM: When fitted and correctly used, the pelham, which is essentially a leverage bit, is very effective – particularly if you need a little bit extra breaking power. The pelham should be used with double reins, with the snaffle rein providing the main point of contact, while the curb rein is left slack until needed. The curb chain should be adjusted and fitted so that the chain links lie flat and hang loose below the chin groove. When the curb rein is tightened, the curb acts as a pivot, increasing the pressure on the bars of the mouth. Due to this configuration, the pelham greatly amplifies your rein aids and requires a much lighter touch. This is definitely not a bit to use on young horses or with inexperienced riders.

KIMBLEWICK: This bit has a curb chain, D-shaped rings, and shanks, and is regarded as a type of curb bit. Used with only one rein, the curb action is much less than that of the pelham due to a greatly reduced capacity for leverage. However, some Kimblewicks are configured to allow the reins to be attached to the rings at different positions, giving the option of increased leverage. The lower the reins are placed, the more effective this bit becomes.

WEYMOUTH: The weymouth is a curb bit designed to be used in conjunction with a plain snaffle, referred to as a bradoon, as part of a double bridle. This combination of two bits, often

K

used at the higher levels of dressage, refines and finesses communication between horse and rider. As with the pelham, care should be taken to ensure that the curb chain is properly fitted and lies flat. The rings of the bradoon are smaller than those of a standard bit to allow for the leverage functioning of the Weymouth. This combination should only be used by very experienced riders on welltrained horses.

K: Eggbutt snaffle L: Full cheek French link M: Gag bit Western bits

English snaffles and curb bits are also used in western riding. The curb encourages the horse to lower their head and flex at the poll, which is the correct way a western horse should move forward. In the western riding style, the curb also assists the rider to guide their horse through neck reining, while holding the reins in one hand only.

GRAZING: Probably one of the most popular western bits, it features angled rather than straight shanks. Some sources say that the curved shanks were originally designed to allow a horse to graze while fully bridled (hence the bit’s name), but others disagree with that theory, adding that for safety’s sake, horses should not eat while wearing a bridle. That aside, the grazing bit usually has a mild or low port (the inverted ‘U’ in the middle of the mouthpiece) and is well suited to many horses.

TOM THUMB: Often mistakenly thought of as a snaffle due to the jointed mouthpiece, the Tom Thumb’s shanks exert leverage, thus putting it firmly in the curb class. There’s also some confusion over its severity. Although the shanks are shorter than those of other curb bits, it cannot be considered to be mild in action as the jointed mouthpiece adds to its severity. Given that’s the case, an inexperienced rider should not be using this bit.

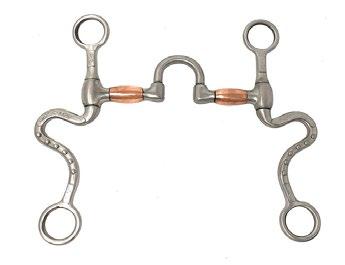

S-SHANK: The ‘S’ shape on the shanks of this bit contribute to the weight, balance, and leverage when the rider applies pressure to the reins, making it more severe than a bit with straight shanks of similar length. The port in the middle of the mouthpiece amplifies the rein aids and provides some relief to the horse’s tongue.

CORRECTION: This bit is intended for training purposes rather than for general everyday riding, and is designed to reinforce rein aids to a horse that is slow to comply. It’s a fairly severe bit, as the length of its shanks suggest, and should only be used by a rider who understands how it works, and also understands how to use rein aids effectively. In the hands of someone less experienced, it could create more problems than it solves. In the hands of an experienced rider, and with a horse that responds well to this kind of bit, it can finesse the communication of the rider’s rein aids to the horse, and, as with a gag bit, can actually be used quite softly.

D-RING SNAFFLE: An attractive and popular choice for showing in-hand and western dressage, this bit is a cross between an eggbutt and a full cheek snaffle. Similar to the eggbutt, it prevents pinching at the corners of the mouth, but without the bulk. The vertical shanks

M

offer fairly significant lateral control without the dangers inherent in the longer shanks of a full cheek snaffle.

It’s all about the hands

The fact is that some people have naturally light hands, some riders have heavier hands. The way the bit works needs to suit the rider as well, often it’s a case of trying a few. A horse that goes well in one bit with one rider, may well need another bit with another rider. Getting the exact size of the bit right is important, and if you are in doubt ask someone to help you measure your horse’s mouth in order to get a good fit. The bit should sit comfortably at the edges of the mouth, without pinching it, but without being too far away from the edges of the mouth either. A bit should not be able to slip through the mouth.

Measuring your horse’s mouth

L

Depending upon their country of origin, the parts of a bit, including the mouthpiece, could be measured in either centimetres or inches, so be prepared. But how do you get a measurement in the first place? Here’re some handy hints:

String: Take a piece of string around 35cms in length. Tie a good sized knot approximately 10cms from one end. Gently place the string in your horse’s mouth where the bit would lie, with the knot against the outside of the lips on one side. Now mark the other end of the string (again, against the lips), and measure between the knot and the mark.

Doweling: You can also use a piece of plain, unpainted doweling. Make a mark at one end in place of a knot, and proceed as if you were using string.

A tape measure: Using a plastic or cloth tape measure, measure from either side of the outside lip with the tape placed across your horse’s mouth in the bit area.

Calipers: These can be handy if you have access to a set. Some have a sliding measurement bar, others look like a giant pair of tweezers. The tweezer variety is probably easiest to use. Adjust the ‘arms’ of the calipers on either side of your horse’s mouth and the distance between the two arms is your mouthpiece measurement.

If the bit fits: Of course, if you have a bit you know fits your horse, measure it from the inside of each cheek piece or ring and you’re good to go!

Where to from here?

The bits we’ve mentioned are only a few of the available options, so clearly, there’s plenty to learn about to make your horse as comfortable as possible with its bit. Brush up your knowledge with a visit to the Bit Bank Australia website, talk to your local saddleries or instructor, and network with friends to get their take on various bits. Perhaps you could borrow one or two that you’re interested in to take for a test drive – after all, it’s always better when it comes straight from the horse’s mouth.