4 minute read

THE BIODÔME’S ECOSYSTEMS

• BY MARION SPÉE

The Biodôme is close to reopening! Its bold architecture provides a brand-new setting for showcasing the beauty of nature and the complex, fragile interrelationships that exist within ecosystems. The visitor experience promises to be more immersive and participatory, but also more moving and introspective.

It has to be said that the subject matter—ingenious, irreplaceable nature—lends itself to this kind of experience. Now—as we are being made increasingly aware of how fragile nature has become in recent decades—is more than ever the time to give it a place of honour. While the Biodôme has a role to play in the conservation of endangered species, it also has a responsibility toward its visitors. The Biodôme team has therefore focused its efforts and attention on ensuring optimum living conditions for its plants and animals, but also on providing a one-of-a-kind experience, with new perspectives, for its visitors.

The Tropical Rainforest, the Laurentian Maple Forest, the Gulf of St. Lawrence, as well as the Sub-Antarctic Islands and the Labrador Coast are still its flagship ecosystems. But, from now on, each will be enveloped by a “living” wall: a curved, fluid, flexible structure. The clean, white surface contrasts sharply with the multisensory profusion of the living collections. In addition, a mezzanine level gives visitors a wonderful vantage point on the individual ecosystems, as well as an overall panorama. The design lets visitors observe the wildlife from above, so that they can appreciate the vital interrelationships between individuals, but also provides a “macro” overview, which is an essential dimension, as the links that exist between species within an ecosystem are what make life possible.

LINKS ESSENTIAL TO LIFE

The Gulf of St. Lawrence, for instance, teems with life. There are all kinds of examples of the relationships among its species. Take plankton, for instance, which consists of both plant organisms (phytoplankton) and animal organisms (zooplankton) that are carried along by the currents. Together, these minute organisms make up the largest aquatic biomass: their total weight is equivalent to the near-totality of the weight of all the other creatures in the sea, including fish, shellfish and whales! What’s more, plankton is the first link in marine food chains. It includes microscopic species as well as others as large as 5 cm in diameter. It is the prey of small predators, which are themselves eaten by larger creatures. Also, big animals like blue whales consume large amounts of plankton. Without plankton, marine species simply couldn’t exist! Plankton is where it all begins.

Another example is the acorn barnacle, a small crustacean resembling a shrimp covered that attaches itself to boat hulls, wrecks, rocks and even whales (especially humpback whales, grey whales and right whales). The acorn barnacle secretes a calcareous carapace (shell) that enables it to remain attached to its host and feed by extending its legs to filter the water and ingest suspended plankton. This relationship between barnacle and host is sometimes referred to as commensalism, but the relationship is not reciprocal, as the barnacle alone benefits from it, although at least it doesn’t bother its host. One interesting finding reported by researchers is that by analysing the composition of fossilized barnacle shells, they were able to retrace whales’ migration routes: it turns out they’ve been following the same routes for 270,000 years!

Likewise in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, real forms of mutualism can be found, such as between the hermit crab and the sea anemone. In mutualism, both species benefit from their relationship with the other. In practice, the anemone attaches itself to the hermit crab so it can move around effortlessly and gain easy access to food, including cleaning up the crab’s leftovers. In return, the crab enjoys added protection against possible predators, which learn to avoid the stinging cells on the anemone’s tentacles. In addition, the anemone produces a horn-like substance that increases the size of the shell the crab is squatting in. As a result, the crab doesn’t have to move house so often. It’s a win-win arrangement.

A hermit crab with an anemone on its shell.

PHOTO Shutterstock/southmind

Through the emphasis it places on a novel, immersive visitor experience, the new Biodôme pays tribute to nature by focusing on how beautiful it is. The goal is straightforward: Leave us marvelling at the wonders of nature and remind us just how valuable biodiversity is. But also awaken our commitment as members of a community to help preserve ecosystems.

People say that an experience has been great if it was a source of pleasure. So we often hear people say, “we love what we know, and protect what we love.” The team at the Biodôme is investing all its energy into ensuring that’s true.

ON THE OTHER HAND

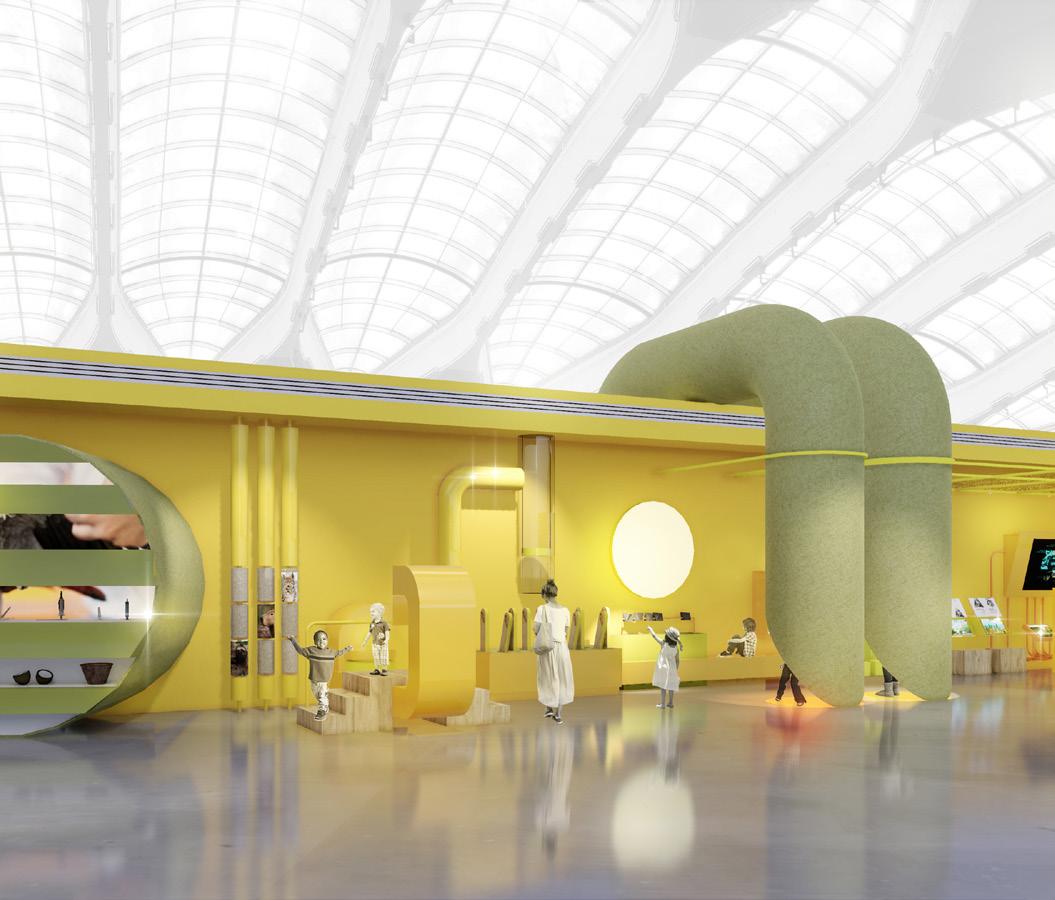

The Bio-machine: A new Biodôme experience, that lets you see what goes on behind the scenes. How do we get the turtles in the Laurentian Maple Forest to hibernate in winter? How do our veterinarians examine wild animals? How do we encourage our animals’ natural behaviour? At 23 interactive stations, which include games, videos and objects, you can now learn more about the tips and tricks used to ensure the care, feeding and general well-being of the Biodôme’s plants and animals. Also, with the video game “Mission: Biodôme Operator,” you can pretend you’re an operator and assume responsibility for maintaining the best possible conditions of water, air and light in the living environments.

IMAGE La bande à Paul