4 minute read

The position of comics in literature

VINCENT TEETSOV

On Estonian second-hand shopping sites like Taaskasutuskeskus Sahtel (literally translated as “used-again drawer”), vintage copies of comics by Olimar Kallas go for as little as four Euros.

Advertisement

For instance, Seiklus Sekontias sundmaandumisega Pelika nisaarel (An Adventure in Sekontia with a Forced Landing on Pelican Island), one of Kallas’ comic books from 1986. It’s used. It’s not in a sealed plastic poly bag. Yet, this six inch by nine inch, 32-page paper comic book has substantially larger cultural value.

The place of comic books in literature is continuing to change. In 2018, the Booker Prize, a British literary award, long-listed Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina (published by Montréal, Québec based publishing company Drawn & Quarterly). However, this change is not without its detractors, as was shown when American comic book writer Stan Lee passed away in 2018. While fans mourned Lee’s death, TV host Bill Maher wrote critically on his blog about comic books, saying that at some point “... adults decided they didn’t have to give up kid stuff. And so they pretended comic books were actually sophisticated literature.”

Even in my formal studies of children’s literature and its techniques in the last few years, the opinion of graphic novels and comics was low. In a sense, it was deemed a distraction from real literature because of the lack of emphasis on words themselves. Some people believed that graphic novels prevent children, particularly young boys, from moving on to reading novels and other longer texts.

Yes, Kallas’ comics were written and illustrated for Estonian children, and of a different era than today’s for that matter. But it serves many of the functions of literature. First and foremost, it entertains.

Kallas published a handful of longer comic books over the years, as well creating caricatures, comics in magazines (such as Pioneer), and other illustrations for books. His first comic book, from 1979, was Kolm Lugu (Three Stories); which contained Toomas ja Krahv (Toomas and Krahv [the Count]), Operatsioon “Mari” (Operation, “Mari”), and Karvane külaline (A Hairy Guest). Every entertaining story needs an eccentric cohort of characters, and Kallas’ comic books delivered on this. Gen-X and early Millennials were introduced to the engineer Noonius, Kraaps the tailor, the beetle researcher Tundel, and a science fiction author named Ulmik.

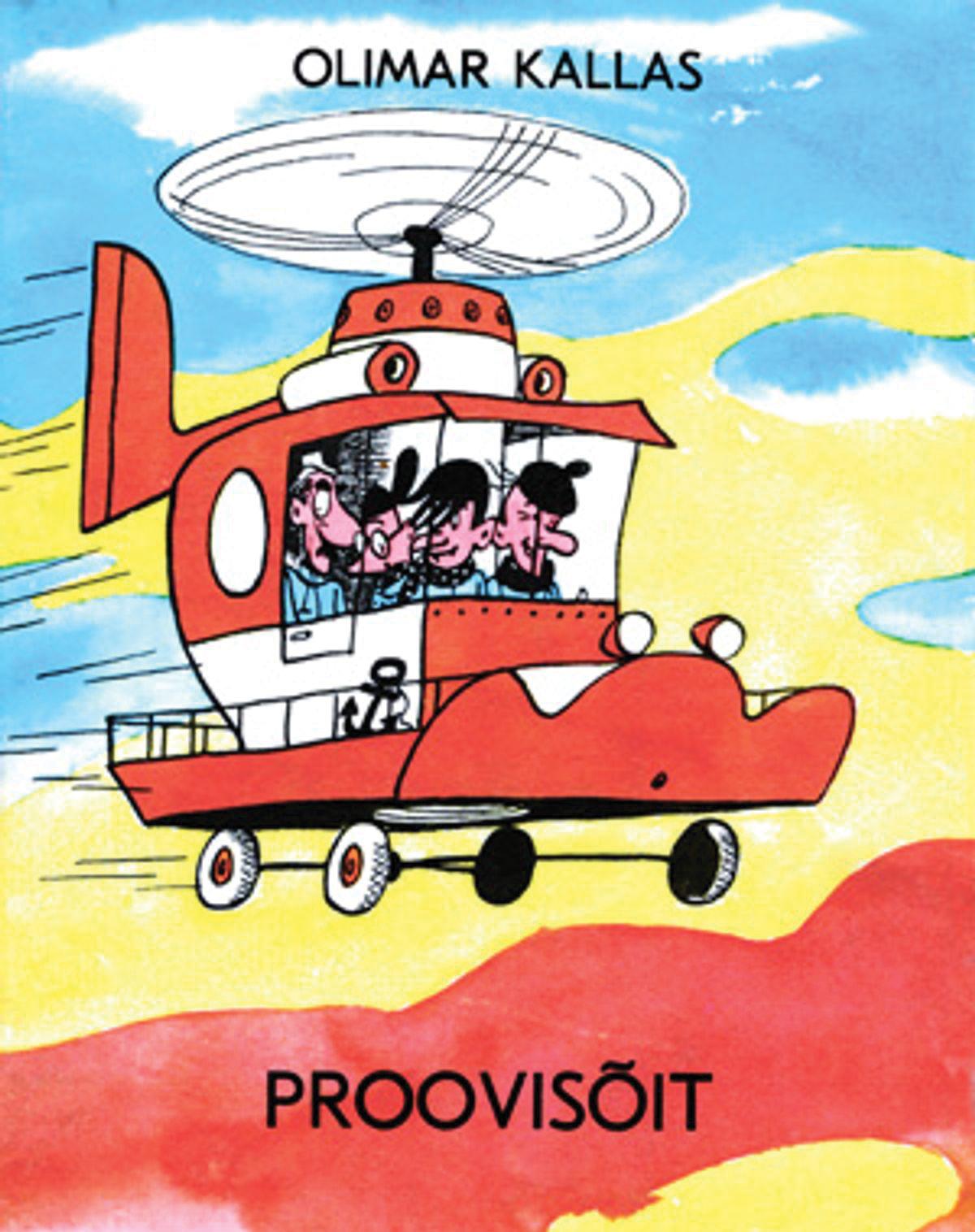

One of his more famous books is Proovisõit (Test Drive), from 1981, in which Noonius and his friends test drive, and eventually have to crash-land the MÕV (referring to Maa-Õhk-Vesi, or “land, air, and sea”) vehicle that he invented. Following this is Seiklus Sekontias sundmaandumisega Pelikanisaarel, where the characters encounter a power hungry antagonist named Pontšik (which is also the name of a donut with powdered sugar on top). Characters are recognizable for their out-of-this-world fashion sense and distinctive facial features. We see the propensity of Kallas to sprinkle absurdities and humour into his comics, alongside action-packed chases, space travel, shady criminals, and other villains.

Other comic book titles of his include the mystery-focused Kevadtriller (Spring Thriller) and Parem käsi tegutseb (The Right Hand Operates). Visually, Kallas’ illustrations are intriguing when he produces shadows with dense application of ink and only a small amount of hatching. There are clearly defined lines and shape boundaries. Quick movements like spinning are shown through black lines. Furthermore, the ink hues in Kallas’ comics are saturated. The hues contrast each other in quite striking ways, and there are less colour variations than, say, Hanna-Barbera cartoons like The Jetsons. However, the sometimes heavy approach to shadow is reminiscent of the ligne claire style made famous by Hergé, creator of The Adventures of Tintin series.

In 2006, Olimar Kallas passed away. Shortly after his death, Eesti Päevaleht published an article paying tribute to his life, noting how comics were considered a lower form of culture during the Soviet occupation. Still, the popularity of his fun stories broke past this snobbery.

In this same year, an anthology of his comics, titled Kogu Lugu (The Whole Story) was published. In Delfi’s Täheke publication for children from January 2007, Jaak Urmet (AKA Wimberg) writes about how his childhood copies of Kallas’ comics were brought everywhere he went, including to the dinner table or the meadow where he sat as his grandfather made hay. His copies were tattered and well-loved, a source of great happiness because, as he notes, comic books were rarely published in Estonia.

One could argue that another purpose of literature is to temporarily exit our own world, and when kids are tired of the limitations of being a kid or face other challenges in life, comics can be a refuge, like a novel might be.

Encyclopaedia Britannica notes that the word “literature” derives from the Latin “littera”, which means “a letter of the alphabet.” Literature is shaped by the use of letters, words, and sentences. Getting down to definitions, comics may not fit the hard definition of literature.

As much as I adore words and their possibilities, though, comics have charm and give us stories in an especially complete package. While comics are driven by drawn shapes and ink, they are clever in their implication of movement in storylines. It’s the same with films, or tales of ghosts around the campfire. The specter of a story, its imprint on time itself, is supreme. Not the medium.

Perhaps we are lost too much in the semantics of titles, or of sections in a library. Comics can tell a story just as capably as a novel if you give it enough space on paper. And the combination of art and words gives our imagination a nudge when the story lingers in our mind after it goes back on the shelf.

You can get ebook copies of Olimar Kallas comics on Kobo or the Rahva Raamat website (rahvaraamat.ee).

The cover of the Olimar Kallas comic book Proovisõit.

Photo: kobo.com