16 minute read

American Adjustment

A Korean American’s journey to find his cultural balance An American ADJUSTMENT

Advertisement

It was 12:51 p.m. on a Saturday afternoon. The sun had just peeked out for the first time from behind the gray rain clouds that filled the Eugene sky. For Jae Chan Lee, today’s weather wasn’t on his mind as he prepped the home of EunHee Kim with cookies and La Croix. His light-blue button-up paired with his dark-blue sweater and round wire glasses completed the look for his professional attire.

This small condo was not the usual kind of property Lee and his real estate company helped to sell. However, Lee made an exception for Kim. As a member of the closely knit Eugene Korean American community, Lee was always willing to help out one of his own.

As the open house began and interested buyers started to arrive, Lee sprang to life. His knowledge of the real estate world went hand-in-hand with his bright, welcoming personality as he interacted with each and every person that walked through the door. The One-and-a-Half Generation

For many immigrants coming to live in the United States, transitioning and adjusting to American culture is a long and difficult road. However, according to a study published by the Association for Psychological Science, this adjustment process is easier for children under the age of 15.

Korean immigrants like Lee, who immigrated to the U.S. at a young age with their parents, are so common that they have their own name: the one-and-a-half generation. They are known to act as a ‘human bridge’ for their relatives, who are usually more set in their homeland’s way of life, and the American culture. UCLA anthropologist Kye Young Park first introduced the term in 1999 to “describe misfits in the Korean community, who were ‘distinct from those of the first- or second-generation ethnic American.’”

The one-and-a-half generation immigrants, or ''Il-chom Ose'' in Korean, arrived in the U.S. as children. Their identities, unlike their first-generation parents or U.S.-born siblings, are split between their birthplace and the country they moved to. This term was used primarily to refer to Korean American immigrants, but it has gained more popularity among other Asian American and Latin American communities.

The one-and-a-half generation children are technically firstgeneration immigrants. However, their experiences are vastly different from older first-generation immigrants. According to the Asian American Society: An Encyclopedia, “The distinguishing characteristics of 1.5ers are that they are conversationally bilingual, bicultural, and able to switch between the two cultures with relative ease," the study reads. The children "have memories of being an immigrant, experienced culture shock, and have felt 'in-between' at times.” Life in Korea

A one-and-a-half generation immigrant himself, Lee, better known as JC in the local community, can relate with other-oneand-a-half generation immigrants and their battles to find a balance between their birth country’s culture and American life. Born in Seoul in 1988 and raised in Seongnam, South Korea, Lee’s life in Korea was spent living in an apartment with his mother, Jong Choi, his father, J.Y. Lee and his older sister, Jennifer Lee. Written by Julia Page Photography by Eric Woodall

Jae Chan Lee poses with his family on the porch of his childhood home in Eugene. Lee’s family built and moved into the house in 2004. Photo by Eric Woodall

Surrounding the family’s five-bedroom apartment was a mixture of residential communities and commercial buildings. With new apartments and shops popping up all the time, a quick walk from his home could lead Lee to the newly built Samsung Plaza, a 10-story shopping mall or neighborhood street food carts. He also recalls frequenting his local ABC Store for school supplies and local arcade rooms as a kid.

Living in one of the most educated countries in the world, the one thing that stood out the most to Lee in South Korea was how rigorous the schooling was in comparison to the U.S. The first 12 years of schooling for every South Korean lead up to a very important test: the Suneung, or the College Scholastic Ability Test. Although it can be equated to the American SAT, this eight-hour test can determine the fate of a student’s life. Not passing the test with flying colors means one more year of preparation for a second chance.

“Life in Korea was pretty intense, like education itself was pretty intense,” Lee says. “You go to school earlier and you even go to school on Saturdays, and when you’re done with school you do other things like personal tutoring, English and piano lessons.”

Within these memories of hard, non-stop schooling, however, were fun memories made between classes. With the weekly allowances he got from his family as a child, one of Lee’s favorite things to spend his money on was food. Living in a country famous for its cuisine, Lee’s small amount of free time was spent trying local foods.

“I used to always go buy fish cakes and spicy rice cakes on the street as a really young kid,” Lee says. “You’d eat and then go and do the studying and then go back home, but when I was coming back home, I would always stop by the food carts.”

Along with the food from local vendors, Lee also found joy in making food at home for him and his sister. His specialty was instant ramen with a twist.

“JC always had really creative ramen recipes, so whenever I wanted to eat ramen, I always asked him to cook ramen for me,” Jennifer Lee says. “He would put in seafood or he would put in bean sprouts. He would add little toppings that I would never try and make it really great.”

Despite these light-hearted memories of growing up in South Korea, the intensity of the country’s schooling paired with a very competitive university and corporate system eventually pushed Choi and J.Y. Lee to move to Eugene, Oregon, with JC Lee and his sister in 1999.

“It’s a system that is very hard to succeed in,” JC says. “The corporate world and drinking culture just doesn’t really have that ‘happy effect’ in the family.”

The drinking culture in South Korea is a known problem, according to the Monsoon Project, a student publication that discusses issues affecting the Asia-Pacific and Australia. “An

With these issues of alcoholism showing links to the harsh, stressful schooling and work environments of South Korea, JC’s parents decided it would be best for their two children to immigrate to the United States. JC's dad, J.Y. Lee, who initially traveled back and forth between South Korea and the U.S., decided to stay in South Korea permanently about 10 years ago.

“His heart is really in South Korea,” Jennifer says. “That’s when my parents kind of decided that my mom wanted to stay here and my dad wanted to stay in Korea.”

The Eugene Experience

After moving to Eugene, where his aunt was already living, JC and his sister started attending school at the local elementary and high schools. Being three years older than JC, Jennifer went to Willamette High School as a freshman, while JC went to Clearlake Elementary School as a sixth-grader.

Although the schools had different names, locations and age groups, there was one thing that both of these schools had in common: the lack of diversity. For JC and Jennifer, the absence of other Asian Americans that they could relate to made it harder for both of them to fit in. Coming from a Korean neighborhood that had little to no white people, becoming racial minorities in the Eugene community was a complete change in perspective.

“It was a rough transition,” Jennifer says. “I was the only Korean girl and I think I was only one of three Asian American students in school. Because I don’t see a lot of my own representation in school, it was hard.”

Even though the siblings had taken English as a required class in South Korea, neither of them were very fluent in the language when they moved to Eugene. As with many child immigrants from non-English speaking countries, JC and Jennifer were both enrolled in an English as a Second Language (ESL) class. With the help of this class, MTV and the radio, JC and Jennifer eventually caught on to the English language.

In contrast to her young children, Choi, a first-generation immigrant who immigrated as an adult, never learned to speak English to the extent that her U.S.-educated children did. Like many one-and-a-half generation immigrants, JC and Jennifer helped break this language barrier for their mother by becoming her translators.

During his first year of schooling, JC struggled to find a sense of belonging among his peers and his community. Although JC's outgoing personality made it easy to make friends and meet new people, he says his sense of self and of his own identity were still in the making.

“I think the first couple years were a little bit difficult,” JC says. “As all Asian Americans, when they first come to America, they are really lost. It takes like three or four years for them to go through that phase.”

North Korea

Seoul

Seongnam

South Korea

One thing that helped JC connect with his fellow classmates was through sports. By playing sports like basketball, baseball and soccer with kids his age, language wasn’t an issue when interacting with other children. Unlike in Seongnam, which JC recalls only having cement and dirt soccer fields, the schools in Eugene had large, green grass fields. Some of JC's best memories in school took place on these fields during recess.

“That’s kind of how I bonded with my friends when I first came,” JC Lee says. “That’s kind of how I learned some English: just by being playful.”

The first few years of living in the U.S. were years of social struggles but also years of personal growth, he says. It was during this transition from the Korean lifestyle to the American way of life that JC and Jennifer's relationship grew stronger. Both JC and Jennifer had to face and experience the same types of personal struggles of being a part of the one-and-a-half generation.

“When we were in Korea, we were kind of far apart because my sister had her friends and I had my friends,” JC says. “But when we came here, we were both Korean American, one-pointfive generation, so we kind of got super tight. We definitely have a special bond between me and my older sister.”

Finding A Balance

It wasn’t until JC was in high school that he began to truly discover who he was as a Korean American.

“When I was in high school, I really didn’t know what I was because there was nobody like me around,” JC says. “But after a while, you kind of find yourself and the fact that you’re able to share the culture with other people who are not really familiar with it.”

Although this way of thinking helped to prompt JC in the right direction towards his desire to find himself, it wasn’t until his time at college that he started to find a balance between his American and Korean identities.

“Korean culture is a very long culture; it’s like 2000 years of history that you have to learn. But when I was in Korea, it didn’t intrigue me that much,” JC says. “But now that I’m here in America and I learned about 200 years of United States history, there’s definitely a lot of depth to Asian history.”

It was in 2009, when JC was still in college, that he started to see where his life path was heading after his mother bought a local Eugene restaurant called Noodle Bowl.

When he first started working at Noodle Bowl, he had no experience with running a restaurant or cooking food other than instant ramen, but after watching many YouTube videos about the craft and creation of Korean cuisine and practicing these skills every day, JC Lee’s knowledge of the Korean culture and cuisine grew.

“For most of my life, I always thought I was the minority, I am different from everyone else here,” JC says. “But as I grew up and learned about my culture more, I really thought that I’m

With dishes such as bibimbap, JC always makes sure customers know that there is a particular way to mix . . . JC sometimes takes it upon himself to mix the dish himself at the table

unique and I want to be able to share my culture, where I came from, with other people from the United States so that they understand what I’m all about.”

Through the restaurant’s food and the interactions he had with his customers, JC was able to showcase his knowledge about the Korean culture.

Although JC Lee and his mother, Choi, had many fights during the first few years of owning and running Noodle Bowl, the mother-and-son duo eventually found their rhythm. Working with each other cooking and serving every day helped strengthen their bond and understanding of one another.

“In the beginning, my mom saw JC as more of a young son. She had to take care of him,” Jennifer says. “But now, the relationship kind of changed and now it’s more JC taking care of my mom, and I can definitely see her depending more on him.”

Life with Noodle Bowl

“He’s really enthusiastic,” Kevin Brown, a long-time server at Noodle Bowl, says about JC. “He cares a lot about the restaurant, so he’s very willing to walk people through the menu and show new people what is what; what’s popular, what’s good, suggest things.”

With dishes such as bibimbap, a Korean rice bowl topped with vegetables and meats, JC always makes sure customers know that there is a particular way to mix, prepare and eat the traditional Korean dish, Brown says. To ensure that the customer won’t just pick at the individual ingredients, JC sometimes takes it upon himself to mix the dish himself at the table.

“Sometimes it’s awesome and they’re totally into it and sometimes they’re like ‘Whoa, what is happening?’” Brown says.

Along with running Noodle Bowl, JC has come to be a part of many organizations throughout the Eugene community, including the Eugene Korean Association, the Oregon Asian Celebration and InEugene Real Estate. With his real estate office only a block away from Noodle Bowl, JC Lee has no problem jumping back and forth between his two jobs and passions.

“If it wasn’t for the church and the volunteering since I was young, I don’t think that I’d be able to do the kind of things that I do right now,” JC says. “Church was the one entity that is all about giving back. It’s not about you, but it’s about giving back.”

For Choi, the Eugene/Springfield Korean Church has seemed to have an even greater effect on her life after immigrating to the U.S. than it had on himself, JC says.

“Finding the church that she really enjoys serving for is one of the key things that she wants to stay here for the rest of her life,” JC says. “She really sees that it was her calling to come to Eugene to be able to to help the church that she serves. Every time she is volunteering for the church and getting involved with the church she feels the most lively at that time.”

A Bridge Between Cultures

When the house-hunters began asking more specific questions about the condo and the area, JC looked to EunHee Kim for answers. Being a first-generation immigrant from Korea, there was a slight language barrier between Kim and the interested buyers. This sense of disconnect was soon broken as JC asked Kim the question in Korean, bridging the language gap with ease. This flow of information, moving from JC to Kim, back to JC, and finally, to the interested buyers, carried on through the open house.

Acting as a bridge between both the Korean community and the Eugene community, as he did at Kim’s open house, will forever be one of JC’s personal jobs as a one-and-a-half generation immigrant. What he’s learned from living in two different worlds with two different ways of speaking and acting has led him to become an active member throughout the communities.

Through his job as a realtor, his restaurant, his organizations and his everyday interactions with the residents of Eugene, JC now feels like Eugene is where he belongs. Living in the U.S. for over 20 years and experiencing life as a one-and-a-half generation Korean American immigrant, he says he feels like he’s made an impact within his community.

“If I go to any other place, I’m really nobody. I’m just another guy who’s just living his life,” JC says. “But being consistent and being persistent of the things that I do on a daily basis, I feel like I really became somebody in this town.”

A story of a young woman’s life in a divided Germany Die Mauer

She didn’t quite understand what she was watching. Sitting in her childhood home outside of East Berlin, Katharina Jones watched an East German official fumble through the announcement: The Berlin Wall was open. Written by Sam Nguyen Illustrations by Eleanor Klock

The late evening news reported that people were moving towards the border. It started as a small trickle of people, unsure but hopeful that what they had heard on the news was true. Unprepared border guards turned them away at first, but people kept coming.

Soon the trickle of people would turn into the largest celebration the world has ever seen.

Jones woke up to her father’s whispering the next morning. She says he beamed with excitement in the darkness. Hearing the news in her father's voice, it finally resonated with her. She could now travel freely between East and West Germany.

In the early morning hours, they drank champagne to the sound of the radio.

After celebrating with her father, Jones headed off to her early-morning nursing shift. Even at work, everyone’s eyes followed the news on television screens. While she was at work, her younger siblings had already entered West Berlin without even showing their identification cards. The barrier of applying for a visa, paying fees and going through interrogation in order to cross into West Germany was gone.

At the end of their work day, Jones and her family walked the Bornholmer Strasse bridge, one of the checkpoints in the Berlin Wall. On the bridge, Jones could barely move with so many people headed towards West Berlin. The stench of gasoil exhaust from the East German Trabant cars trying to cross remains with her to this day.

On the other side of the Wall, welcoming West Berliners awaited. People greeted each other with hugs, laughter and tears. They drank and danced with strangers as if they were old friends. People exchanged their stories with each other. Previously intimidating and removed police officers became friendly and joined the celebrating masses.

It was a party for the birth of a new Germany.

Geteilte Deutschland

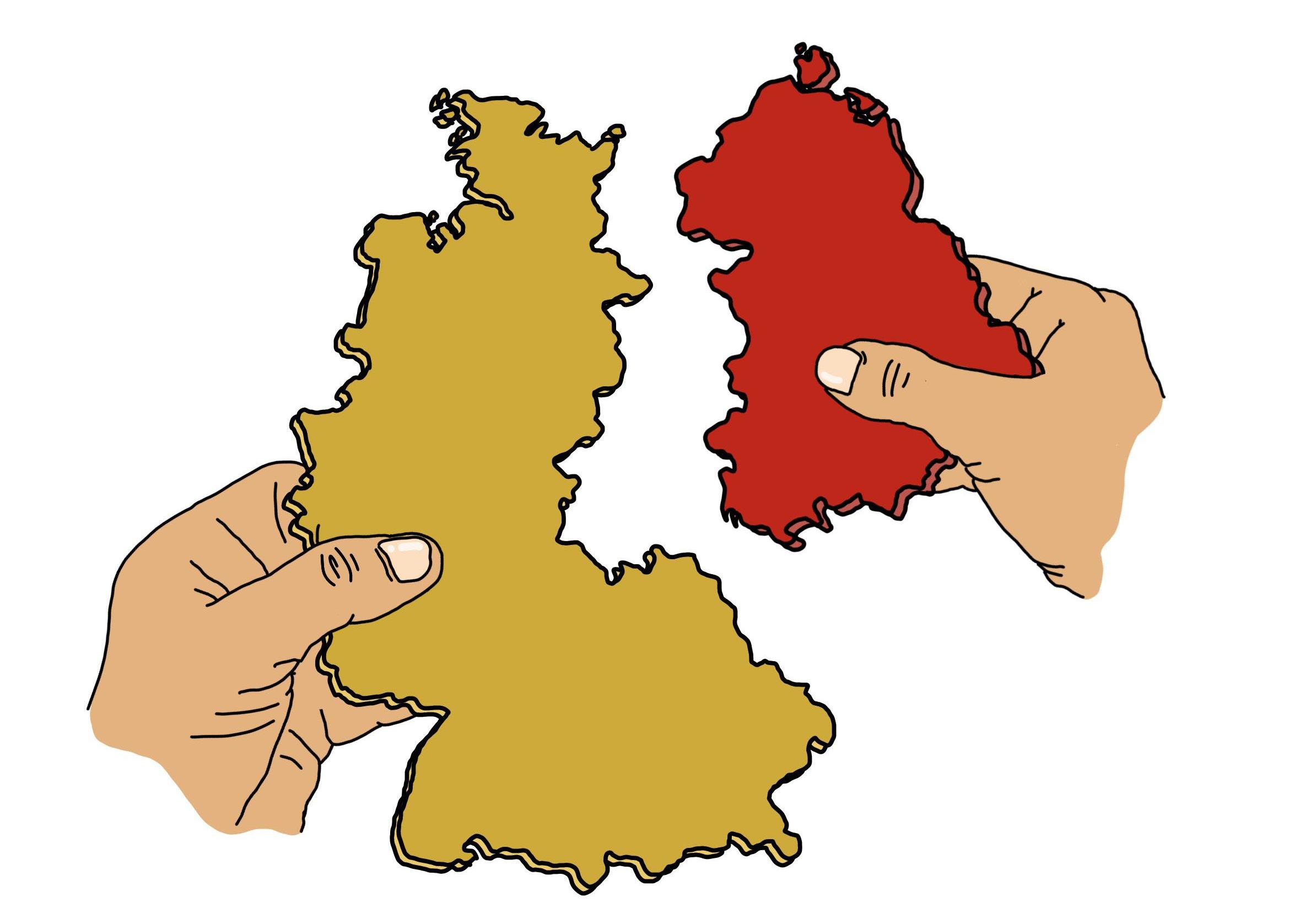

After World War II, with Germany defeated, the Allies decided that they would split the country into four zones, each occupied by one of the Allies. Although Germany’s capital was in the East, Berlin was also split into four by the Allies. Seven years later, in 1952, the U.S.S.R. decided to close the border between West and East Germany, officially setting up the Iron Curtain that divided the capitalist and socialist powers.

Losing their ability to travel to the West, many East Germans turned to the more accessible West Berlin. To stem the East Germans leaving the country, the German Democratic Republic (GDR) started constructing a wall that divided West and East Berlin in 1961. The Berlin Wall, which stood for 28 years, was a