7 minute read

ARTS & CULTURE ARTS & CULTURE The Art of Less The Art of Less

Now on display, the Cincinnati Art Museum’s Alice F. and Harris K. Weston Collection features 18 works by post-modern and contemporary artists.

BY STEVEN ROSEN

BY STEVEN ROSEN

For those looking for an artwork of exquisite minimalism, Sol LeWitt’s Atlantic City Piece (1971), now at Cincinnati Art Museum, is the visual equivalent of one hand clapping. It’s kind of only partly there, but the allure of it — the idea of it — brings it to full, vivid life.

For those looking for an artwork of exquisite minimalism, Sol LeWitt’s Atlantic City Piece (1971), now at Cincinnati Art Museum, is the visual equivalent of one hand clapping. It’s kind of only partly there, but the allure of it — the idea of it — brings it to full, vivid life.

e piece only exists as a drawing on a gallery wall. After being physically created, it went on view at the museum in August. In contemporary art, anything is potentially a material and can be drawn or painted upon, and an artwork can be site-speci c and durational.

e piece only exists as a drawing on a gallery wall. After being physically created, it went on view at the museum in August. In contemporary art, anything is potentially a material and can be drawn or painted upon, and an artwork can be site-speci c and durational.

But one strange thing in this case is that the artist, LeWitt, died in 2007 at age 78, so he wasn’t there to actually draw the work on the wall, nor even to supervise apprentices. A museum art handler, Bobby Burke, did the actual hands-on work, using a framed set of instructions provided by LeWitt.

But one strange thing in this case is that the artist, LeWitt, died in 2007 at age 78, so he wasn’t there to actually draw the work on the wall, nor even to supervise apprentices. A museum art handler, Bobby Burke, did the actual hands-on work, using a framed set of instructions provided by LeWitt.

Another stumper: the artwork at rst looks like a blank space on a white gallery wall. e area where it’s located has a notably lighter whiteness from the rest of the wall, as if something that once

Another stumper: the artwork at rst looks like a blank space on a white gallery wall. e area where it’s located has a notably lighter whiteness from the rest of the wall, as if something that once had been there for years was removed and the area revealed is free of any grit or grime that comes with exposure. Visitors have to get close to see the actual art, and even then keep an open mind and laser-focused eye to see the faint, somewhat unsteady, pale-yellow pencil lines that form a somewhat shaky grid within a ve-square-foot space. had been there for years was removed and the area revealed is free of any grit or grime that comes with exposure. Visitors have to get close to see the actual art, and even then keep an open mind and laser-focused eye to see the faint, somewhat unsteady, pale-yellow pencil lines that form a somewhat shaky grid within a ve-square-foot space.

If it were a three-dimensional sculpture, it’d be roped-o so people can’t get too close.

If it were a three-dimensional sculpture, it’d be roped-o so people can’t get too close.

It’s mesmerizing; humbling, even. Ghostly and seemingly ephemeral, like a fading rainbow, it’s all the more beautiful and emotionally charged because of it. It persists in existing despite our inclination to overlook it — a metaphor for art itself. And, really, for us.

It’s mesmerizing; humbling, even. Ghostly and seemingly ephemeral, like a fading rainbow, it’s all the more beautiful and emotionally charged because of it. It persists in existing despite our inclination to overlook it — a metaphor for art itself. And, really, for us.

Atlantic City Piece (1971) debuted at the museum as part of a show o ering highlights from a 2019 bequest from Alice and Harris Weston. ey were longtime visual arts supporters and collectors in Cincinnati, especially receptive to contemporary art. Harris died in 2009, followed by Alice in 2019. is exhibit will be on view in a rst- oor

Atlantic City Piece (1971) debuted at the museum as part of a show o ering highlights from a 2019 bequest from Alice and Harris Weston. ey were longtime visual arts supporters and collectors in Cincinnati, especially receptive to contemporary art. Harris died in 2009, followed by Alice in 2019. is exhibit will be on view in a rst- oor gallery — e Alice F. and Harris K. Weston Collection of Post-World War II Modern and Contemporary Art — at least through Jan. 2024, so Atlantic City Piece (1971) will be there for quite a while and is worth a special trip. gallery — e Alice F. and Harris K. Weston Collection of Post-World War II Modern and Contemporary Art — at least through Jan. 2024, so Atlantic City Piece (1971) will be there for quite a while and is worth a special trip.

But what happens when LeWitt’s artwork must come down? Do they have to tear out and preserve the chunk of wall upon which it’s drawn? According to an email from Cynthia Amnéus, the museum’s chief curator, it just disappears until the next time it’s displayed, though the museum still technically has access to the set of instructions LeWitt provides to recreate it in the future.

But what happens when LeWitt’s artwork must come down? Do they have to tear out and preserve the chunk of wall upon which it’s drawn? According to an email from Cynthia Amnéus, the museum’s chief curator, it just disappears until the next time it’s displayed, though the museum still technically has access to the set of instructions LeWitt provides to recreate it in the future.

“What we have in the collection is a framed set of instructions,” she tells CityBeat. “LeWitt wanted these pieces to live on and notes that, ‘each person

“What we have in the collection is a framed set of instructions,” she tells CityBeat. “LeWitt wanted these pieces to live on and notes that, ‘each person draws a line di erently and each person understands words di erently,’ so the execution is di erent each time.” draws a line di erently and each person understands words di erently,’ so the execution is di erent each time.” e museum does have plenty of LeWitt artwork in its collection, mostly light sensitive prints, but Amnéus believes this to be its rst wall drawing by him. e museum does have plenty of LeWitt artwork in its collection, mostly light sensitive prints, but Amnéus believes this to be its rst wall drawing by him.

Really, the whole show is rewarding for some unusual reasons. Many of the 18 works available for viewing are relatively small and leave a lot of open space in the gallery. Since the Westons collected minimalist art as well as examples of Pop art and earlier movements, the gallery underscores the subtle sublimity of the best pieces — visitors have to look closer, try harder, to fully appreciate the work. In doing that, they form a closer connection.

Really, the whole show is rewarding for some unusual reasons. Many of the 18 works available for viewing are relatively small and leave a lot of open space in the gallery. Since the Westons collected minimalist art as well as examples of Pop art and earlier movements, the gallery underscores the subtle sublimity of the best pieces — visitors have to look closer, try harder, to fully appreciate the work. In doing that, they form a closer connection.

Among the other artists with ne, rewarding pieces are Andy Warhol, Josef Albers, Joseph Cornell, Tom Wesselmann, Carl Andre, Alan Son st and more.

Besides the LeWitt piece, several others especially stand out. To the right of the LeWitt, if you’re facing it straight-on, is a Dan Flavin uorescent tube tucked into a corner where two walls meet the oor. is 1976 artwork, titled Untitled (Fondly, to Helen), is much easier to see than the LeWitt — the white, green and yellow lighting glow brilliantly. It’s a beacon; a virtual lighthouse amid the other work in the gallery.

Flavin, who died in 1996, is a very familiar name in the art world, but this is Cincinnati Art Museum’s rst sculpture by him. Many people over the years have wondered what the heck a uorescent light is doing in a museum instead of an o ce. ey can’t get past its common function to see it as a sculpture. Flavin is teaching us that no object is inherently mundane and boring. It just waits for a visionary person to see it in a new way and then share it.

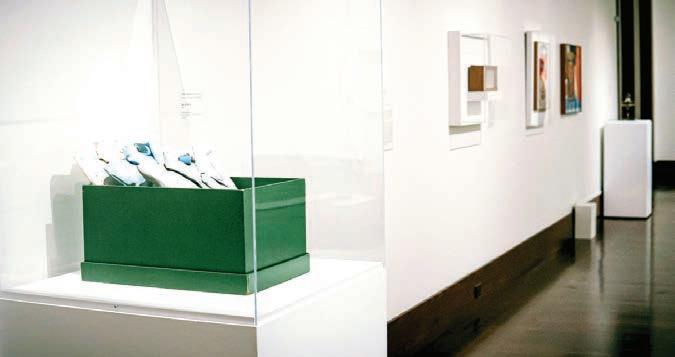

Claes Oldenburg, who died in 2022, also liked to mess with our heads, and Box of Shirts — his rst sculpture to enter the art museum’s collection, although the museum has seven of his prints — has that kind of impact.

It’s an early piece for him, from 1964 when he was just 34 and still an emerging name in Pop art ( is was the Westons’ rst purchase of a Pop artwork).

On display in a vitrine that reminds one of a clothing store’s glass display case, it really seems to be a box of shirts. ey look carefully folded and placed by each other — a gray, a powder blue, a white one with patterns. But in fact, these are oil-painted on canvas and in a wood bin. Oldenburg once did a whole store of this kind of art, and his sculptures are as much a weird and memorable product of Pop art as Warhol’s soup cans, one of which is also in the Weston collection.

One perhaps shouldn’t suggest that, with contemporary art, small is better than big. e Westons’ collection was chosen to t comfortably in their East Walnut Hills home. e art museum has some excellent large contemporary pieces in its collection and should pursue more, including more by those who are underrepresented ( ere is a new Weston endowment for the purchase and preservation of contemporary art). But when relatively small pieces are as rewarding as these, it’s a big treat.