32 minute read

ARTS & CULTURE

ARTS & CULTURE ARTS & CULTURE

Adelia Killian hopes that her content inspires others to feel comfortable in their own skin.

PHOTO: ADELIA KILLIAN

TikTok and the City TikTok and the City Cincinnati resident and TikTok in uencer Adelia Killian aims to change Cincinnati resident and TikTok in uencer Adelia Killian aims to change the plus-size in uencer industry. the plus-size in uencer industry. BY BRYN DIPPOLD

BY BRYN DIPPOLD

Adelia Killian’s marketing instincts kicked in early.

At the age of 10, Killian, whose birth name was Lauren, knew that her middle name, Adelia, t her better. At the age of 18, she o cially changed her name to Adelia.

“Adelia always felt more ‘me,’” she says. “In school, I was never the only Lauren and I always loved how unique Adelia is. I quickly attached my identity to it.”

Now the 25-year-old in uencer and Cincinnatian has made her name her brand, known as “AdeliaLaughs” on Instagram and TikTok.

On Instagram, Killian posts about plus-sized fashion and her personal life – with the streets of Cincinnati and her bright,airy apartment as the backdrop – to more than 15,600 followers. Her TikTok audience of almost 200,000 followers receives similar content, including videos about “romanticizing” the Midwest, how to dress trendy at any size and content for expectant mothers.

“I love variety,” Killian says. “I never want to pigeonhole myself into just one area of content.”

Before Killian’s career moved to TikTok and Instagram, she started a blog called “She Laughs” in January 2018 while attending Miami University in Oxford. e blog, which Killian still runs, is about lifestyle, health, beauty and fashion.

At Miami, she was on the pre-med track and majored in philosophy and French, but after about a year of running her blog, Killian decided to go a di erent route. She got a corporate job in in uencer marketing after graduating in 2019, one that she says particularly prepared her to become an in uencer.

“If you’re not going viral, if you’re not developing a brand or platform early, then it might not happen,” Killian says.

When Killian rebooted her TikTok in May 2021, she had planned videos and a strategy of building her brand. Just a month later, her TikTok about wearing whatever you want at any size went viral.

“I feel like everyone’s story these days sounds like this, but basically, I blew up on TikTok one time and then everything changed,” Killian says.

Being online does come with its downsides, though – especially as a plus-size content creator. ough Killian has received negative and bullying comments about her body, she says that she is able to deal with it because of an eating disorder when she was young.

“I recovered at a very young age, so with that I had zero tolerance with body shaming,” Killian says. “I was going through puberty already fed up with diet culture, with fat shaming and anything of the sort. When I rst launched my website and my brand, I wanted it to be less about lifestyle and a lot more about positivity, about growth and about con dence. I wanted to be the ‘inspo-Pinterest-girly’ for bigger people.” ough Killian feels con dent with her body and her image, there are some things she wishes she would have been clearer about when she rst gained a following on TikTok.

“For me, as a creator, I wish I was much more comfortable and open about fatphobia and other struggles of being in a bigger body,” she says. “I wish I was more open in the beginning or more ready to take down the bullshit, if you will.”

Killian and her husband, Connor, recently announced that they’re

expecting their rst child, just a few months after she was laid o from her corporate job and decided to make content full-time in July 2022. is was a change she had considered since March of this year. “For me, I rst considered going full-time back in March this year when I had one month of blog income that surpassed the income I had with my day job,” she wrote on her blog She Laughs in Sept. 2022. “I quickly ignored that thought in my head because while I was reaching some smaller goals with my business, those ‘good months’ as I call them were still too sporadic. At the time the idea of holding onto predictable income seemed like the smart thing to do.” e decision was made for her when she was laid o . “I knew this was the sign I needed to go full-time,” she wrote. “I had hoped to have a more stable nancial picture, but the past few months of planning and strategizing campaigns and other projects has me signi cantly more hopeful for our future.” Now, as an expecting mother, Killian is clear about how that might change her content and platform. “I want to share cute little family moments here or there, but I’m against family vlogging,” she says. Family vlogging, in which social media in uencers lm and share details about their partner and children, increasingly has been seen as controversial, Killian notes. e in uencer knows that “small details can cause massive problems,” A delia Killian’s marketing instincts kicked in early. At the age of 10, Killian, such as a picture of her child wearing a school insignia, a street sign in the background or even sharing her child’s whose birth name was Lauren, knew favorite color. “A person could go up that her middle name, Adelia, t her to my child and pretend they know me better. At the age of 18, she o cially and know them because they know changed her name to Adelia. these little details,” Killian says.

“Adelia always felt more ‘me,’” she e privacy and safety of her child is says. “In school, I was never the only of utmost importance to Killian. Lauren and I always loved how unique Killian says her child will get to Adelia is. I quickly attached my identity decide whether or not they want to be to it.” in videos when they’re 14 years old.

Now the 25-year-old in uencer and Until then, she says she will continue to Cincinnatian has made her name her share the types of content that has gotbrand, known as “AdeliaLaughs” on ten her to where she is now. Instagram and TikTok. Killian says she wants two things to

On Instagram, Killian posts about come across to TikTok users who nd plus-sized fashion and her personal life her while casually scrolling. – with the streets of Cincinnati and her “One, I want people to understand bright,airy apartment as the backdrop that insecurity is a waste of time. Two, – to more than 15,600 followers. Her I want people to leave with a nugget TikTok audience of almost 200,000 fol- of wisdom around personal style and lowers receives similar content, includ- fashion,” Killian says. “I want to instill ing videos about “romanticizing” the con dence. And I want to encourage Midwest, how to dress trendy at any size people to look at themselves and appreand content for expectant mothers. ciate themselves for who they are.”

“I love variety,” Killian says. “I never want to pigeonhole myself into just one area of content.”

Before Killian’s career moved to TikTok and Instagram, she started a blog called “She Laughs” in January 2018 while attending Miami University in Oxford. e blog, which Killian still runs, is about lifestyle, health, beauty and fashion. At Miami, she was on the pre-med track and majored in philosophy and French, but after about a year of running her blog, Killian decided to go a di erent route. She got a corporate job in in uencer marketing after graduating in 2019, one that she says particularly prepared her to become an in uencer. “If you’re not going viral, if you’re not developing a brand or platform early, then it might not happen,” Killian says. When Killian rebooted her TikTok in May 2021, she had planned videos and a strategy of building her brand. Just a month later, her TikTok about wearing whatever you want at any size went viral. “I feel like everyone’s story these days sounds like this, but basically, I blew up on TikTok one time and then everything changed,” Killian says. Being online does come with its downsides, though – especially as a plus-size content creator. ough Killian has received negative and bullying comments about her body, she says that she is able to deal with it because of an eating disorder when she was young. “I recovered at a very young age, so with that I had zero tolerance with body shaming,” Killian says. “I was going through puberty already fed up with diet culture, with fat shaming and anything of the sort. When I rst launched my website and my brand, I wanted it to be less about lifestyle and a lot more about positivity, about growth and about con dence. I wanted to be the ‘inspo-Pinterest-girly’ for bigger people.” ough Killian feels con dent with her body and her image, there are some things she wishes she would have been clearer about when she rst gained a following on TikTok. “For me, as a creator, I wish I was much more comfortable and open about fatphobia and other struggles of being in a bigger body,” she says. “I wish I was more open in the beginning or more ready to take down the bullshit, if you will.” Killian and her husband, Connor, recently announced that they’re expecting their rst child, just a few months after she was laid o from her corporate job and decided to make content full-time in July 2022. is was a change she had considered since March of this year. “For me, I rst considered going full-time back in March this year when I had one month of blog income that surpassed the income I had with my day job,” she wrote on her blog She Laughs in Sept. 2022. “I quickly ignored that thought in my head because while I was reaching some smaller goals with my business, those ‘good months’ as I call them were still too sporadic. At the time the idea of holding onto predictable income seemed like the smart thing to do.” e decision was made for her when she was laid o . “I knew this was the sign I needed to go full-time,” she wrote. “I had hoped to have a more stable nancial picture, but the past few months of planning and strategizing campaigns and other projects has me signi cantly more hopeful for our future.” Now, as an expecting mother, Killian is clear about how that might change her content and platform. “I want to share cute little family moments here or there, but I’m against family vlogging,” she says. Family vlogging, in which social media in uencers lm and share details about their partner and children, increasingly has been seen as controversial, Killian notes. e in uencer knows that “small details can cause massive problems,” such as a picture of her child wearing a school insignia, a street sign in the background or even sharing her child’s favorite color. “A person could go up to my child and pretend they know me and know them because they know these little details,” Killian says. e privacy and safety of her child is of utmost importance to Killian. Killian says her child will get to decide whether or not they want to be in videos when they’re 14 years old. Until then, she says she will continue to share the types of content that has gotten her to where she is now. Killian says she wants two things to come across to TikTok users who nd her while casually scrolling. “One, I want people to understand that insecurity is a waste of time. Two, I want people to leave with a nugget of wisdom around personal style and fashion,” Killian says. “I want to instill con dence. And I want to encourage people to look at themselves and appreciate themselves for who they are.”

Learn more about Adelia Killian Learn more about Adelia Killian on Instagram and TikTok by on Instagram and TikTok by searching for @adelialaughs. searching for @adelialaughs. Info: adelialaughs.com. Info: adelialaughs.com.

CULTURE CULTURE A New Exhibit at Hebrew Union College’s Skirball Museum A New Exhibit at Hebrew Union College’s Skirball Museum Explores the Legacy of Cincinnati’s Jewish Community

BY TYLER FRIEDMAN

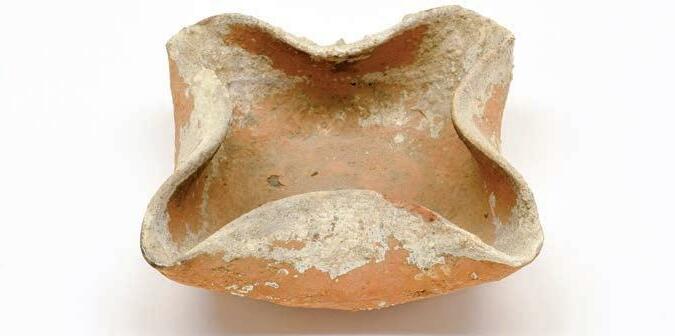

Qumran Jar and Lid Palestine, 100 BCE—100 CE Qumran Jar and Lid Palestine, 100 BCE—100 CE Pottery, jar: h. 24 x dia. 16 in.; lid: h. 8 x dia. 10 in. Pottery, jar: h. 24 x dia. 16 in.; lid: h. 8 x dia. 10 in. Cincinnati Skirball Museum, gift of Jack and Audrey Skirball, a/869A-B. Cincinnati Skirball Museum, gift of Jack and Audrey Skirball, a/869A-B. PHOTO: PROVIDED BY CINCINNATI SKIRBALL MUSEUM

PHOTO: PROVIDED BY CINCINNATI SKIRBALL MUSEUM

Memory is a big deal in Judaism. Zakhor—the Hebrew imperative meaning “remember”—appears upwards of 200 times in the rst ve books of the Hebrew Bible. e exhortation has served Jews well. Over a millennia of diasporic dispersal, the Jewish people remained a people precisely by virtue of heeding the calls to remember commandments, traditions and holidays. Institutions played a central role in preserving memory, continuing to facilitate remembrance to this day.

Hebrew Union College’s Skirball Museum in Cincinnati’s CUF neighborhood is one such bastion of Jewish memory. Its collection spans a broad swath of Jewish history, encompassing both art and archaeology. Among its historical artifacts are archaic oil lamps dating back thousands of years to the Middle Bronze Age.

A new exhibition at the Skirball is an exercise in remembrance. Jewish Cincinnati: A Photographic Record presents 36 works by artist J. Miles Wolf that merge architectural photography and archival images into collaged aides-mémoire that document Cincinnati’s illustrious Jewish past and the traces that have survived into the present. e Skirball Museum’s collection contains several Jewish artifacts, like an unassuming two-foot-tall pottery vessel. When discovered in 1947, this Qumran jar—named after the site on the western bank of the Dead Sea—contained seven scrolls representing some of the earliest surviving manuscripts of the Bible. “ e Dead Sea Scrolls o er unparalleled insight into ancient Jewish life,” explains Abby Schwartz, director of the Skirball. “And the Qumran jar is a tangible connection to these communities.”

As for art, Schwartz points to a marble bust of Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise from 1903 as a collection highlight.

“You can’t overstate Wise’s impact on American Judaism,” Schwartz tells CityBeat. “He gave birth to the Reform movement, founded Hebrew Union College, built the Plum Street Temple, and founded the Central Conference of American Rabbis.” e signi cance of the bust, crafted by Jewish sculptor Moses Jacob Ezekiel, goes beyond its subject. It also is believed to be the rst three-dimensional image of a rabbi in art history. Exodus 20:4-6 pronounces, “You shall not make for yourself an image in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below.” roughout Jewish history, this prohibition has been observed with varying degrees of exactitude; but such a lifelike bust is the nal frontier of graven images. e works in the Jewish Cincinnati exhibition are acts of artistic reclamation, with sepia photos of places and faces superimposed atop present-day locations. Where the buildings and their environs have survived in their original condition, the combination of past and present is seamless. In other cases, the juxtaposition is as jarring as shrimp at a seder. Eighteen of the works, which focus on houses of worship, were displayed at the Skirball as part of the 2018 FotoFocus Biennial, according to Schwartz. e enthusiastic reception of the rst exhibition convinced Wolf to continue his research. “Searching for old photographs is like a treasure hunt,” Wolf says. “I’ve looked in dozens of places: the American Jewish Archives, the Museum Center’s Cincinnati History Library and Archive,

synagogues in Cincinnati and Kentucky as well as their members and descendants of past members.” Wolf’s tireless search uncovered forgotten photographs, occasionally with assistance from serendipity. “I was researching the West Side Sephardic synagogue Beth Sholom and came across an uncommon last name, Ouziel, which happened to be the last name of someone I went to high school with.” e schoolmate provided photos and put Wolf in contact with the widow of Beth Shalom’s former rabbi who, in turn, had photographs of her husband as well as his grandfather, Rabbi Jeruzalmi of Turkey. e two rabbis and a family photo with Albert Ouziel as a ve-year old boy are featured in the work of M emory is a big deal in Judaism. Zakhor—the Hebrew imperative meanart entitled “Beth Sholom, Price Hill, Cincinnati 1933-1992.” Wolf used an archival photograph of the synagogue itself, which has been converted to a ing “remember”—appears upwards of Hispanic church with the Star of David 200 times in the rst ve books of the removed and the name of the building Hebrew Bible. covered up. e exhortation has served Jews well. Many of the 18 new images in Jewish Over a millennia of diasporic dispersal, Cincinnati: A Photographic Record at the Jewish people remained a people the Skirball Museum focus on Jewprecisely by virtue of heeding the calls ish contributions to culture and their to remember commandments, tradirole in Cincinnati’s industrial golden tions and holidays. Institutions played age. “Many people recognize the name a central role in preserving memory, ‘Manischewitz’ as a giant of the kosher continuing to facilitate remembrance to foods industry,” explains Wolf. “But most this day. people don’t realize that the company

Hebrew Union College’s Skirball got its start in Cincinnati and was active Museum in Cincinnati’s CUF neighhere for 100 years.” For millennia, matzo borhood is one such bastion of Jewish was handmade and consumed locally. memory. Its collection spans a broad Even with the emergence of mass swath of Jewish history, encompassing production in the food industry, the both art and archaeology. Among its meticulousness of the laws of kashrut historical artifacts are archaic oil lamps kept matzo a small batch product. dating back thousands of years to the Rabbi Dov Behr Manischewitz’s innovation was to produce matzo with a

Middle Bronze Age.

A new exhibition at the Skirball is an exercise in remembrance. Jewish Cincinnati: A Photographic Record presents 36 works by artist J. Miles Wolf that merge architectural photography and archival images into collaged aides-mémoire that document Cincinnati’s illustrious Jewish past and the traces that have survived into the present. e Skirball Museum’s collection contains several Jewish artifacts, like an unassuming two-foot-tall pottery vessel. When discovered in 1947, this Qumran jar—named after the site on the western bank of the Dead Sea—contained seven scrolls representing some of the earliest surviving manuscripts of the Bible. “ e Dead Sea Scrolls o er unparalleled insight into ancient Jewish life,” explains Abby Schwartz, director of the Skirball. “And the Qumran jar is a tangible connection to these communities.”

As for art, Schwartz points to a marble bust of Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise from 1903 as a collection highlight.

“You can’t overstate Wise’s impact on American Judaism,” Schwartz tells CityBeat. “He gave birth to the Reform movement, founded Hebrew Union College, built the Plum Street Temple, and founded the Central Conference of American Rabbis.” e signi cance of the bust, crafted by Jewish sculptor Moses Jacob Ezekiel, goes beyond its subject. It also is believed to be the rst three-dimensional image of a rabbi in art history. Exodus 20:4-6 pronounces, “You shall not make for yourself an image in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below.” roughout Jewish history, this prohibition has been observed with varying degrees of exactitude; but such a lifelike bust is the nal frontier of graven images. e works in the Jewish Cincinnati exhibition are acts of artistic reclamation, with sepia photos of places and faces superimposed atop present-day locations. Where the buildings and their environs have survived in their original condition, the combination of past and present is seamless. In other cases, the juxtaposition is as jarring as shrimp at a seder. Eighteen of the works, which focus on houses of worship, were displayed at the Skirball as part of the 2018 FotoFocus Biennial, according to Schwartz. e enthusiastic reception of the rst exhibition convinced Wolf to continue his research. “Searching for old photographs is like a treasure hunt,” Wolf says. “I’ve looked in dozens of places: the American Jewish Archives, the Museum Center’s Cincinnati History Library and Archive, synagogues in Cincinnati and Kentucky as well as their members and descendants of past members.”

Wolf’s tireless search uncovered forgotten photographs, occasionally with assistance from serendipity.

“I was researching the West Side Sephardic synagogue Beth Sholom and came across an uncommon last name, Ouziel, which happened to be the last name of someone I went to high school with.” e schoolmate provided photos and put Wolf in contact with the widow of Beth Shalom’s former rabbi who, in turn, had photographs of her husband as well as his grandfather, Rabbi Jeruzalmi of Turkey. e two rabbis and a family photo with Albert Ouziel as a ve-year old boy are featured in the work of art entitled “Beth Sholom, Price Hill, Cincinnati 1933-1992.” Wolf used an archival photograph of the synagogue itself, which has been converted to a Hispanic church with the Star of David removed and the name of the building covered up.

Many of the 18 new images in Jewish Cincinnati: A Photographic Record at the Skirball Museum focus on Jewish contributions to culture and their role in Cincinnati’s industrial golden age. “Many people recognize the name ‘Manischewitz’ as a giant of the kosher foods industry,” explains Wolf. “But most people don’t realize that the company got its start in Cincinnati and was active here for 100 years.” For millennia, matzo was handmade and consumed locally. Even with the emergence of mass production in the food industry, the meticulousness of the laws of kashrut kept matzo a small batch product.

Rabbi Dov Behr Manischewitz’s innovation was to produce matzo with a

Oil Lamp Canaanite from Sinijil, Middle Bronze Age 1, 2400-2000 BCE Oil Lamp Canaanite from Sinijil, Middle Bronze Age 1, 2400-2000 BCE Clay Clay Cincinnati Skirball Museum, HUC 5902. Cincinnati Skirball Museum, HUC 5902. PHOTO: PROVIDED BY CINCINNATI SKIRBALL MUSEUM

PHOTO: PROVIDED BY CINCINNATI SKIRBALL MUSEUM

Portrait Bust of Isaac Mayer Wise Moses Jacob Ezekiel (Richmond, VA 1844–1917 Rome, Italy) Portrait Bust of Isaac Mayer Wise Moses Jacob Ezekiel (Richmond, VA 1844–1917 Rome, Italy) Carrara marble, 1903 Carrara marble, 1903 Cincinnati Skirball Museum, gift of Isaac Mayer Wise heirs, 67.123. Cincinnati Skirball Museum, gift of Isaac Mayer Wise heirs, 67.123. PHOTO: PROVIDED BY CINCINNATI SKIRBALL MUSEUM

PHOTO: PROVIDED BY CINCINNATI SKIRBALL MUSEUM

process involving three machines—one to knead the dough, one to roll it, and one to re it—ensuring strict adherence to kosher standards. us Manischewitz became the rst company to sell rabbinically-approved kosher foods nationally and internationally.

Also represented is Lipman Pike, the rst professional Jewish baseball player. “Pike was known for his power and speed on the baseball diamond,” says Wolf. He was powerful enough to lead the league in home runs for four seasons and fast enough to have beaten a horse in a 100-yard sprint, according to a biography of Pike by the Society for American Baseball Research. Pike served a brief stint with the Cincinnati Reds in the late 1870s as center elder and de facto manager.

In addition to his subjects’ compelling historical backgrounds, the aesthetic e ect of Wolf’s photographs is enhanced by subtle artistic decisions, says

process involving three machines—one to knead the dough, one to roll it, and one to re it—ensuring strict adherence to kosher standards. us Manischewitz became the rst company to sell rabbinically-approved kosher foods nationally and internationally. Also represented is Lipman Pike, the rst professional Jewish baseball player. “Pike was known for his power and speed on the baseball diamond,” says Wolf. He was powerful enough to lead the league in home runs for four seasons and fast enough to have beaten a horse in a 100-yard sprint, according to a biography of Pike by the Society for American Baseball Research. Pike served a brief stint with the Cincinnati Reds in the late 1870s as center elder and de facto manager. Schwartz. He sets most of his images against a twilight sky. e transitional state between day and night enhances the dreamlike e ect of merging the past and the present. Wolf’s deliberately slow shutter speed captures the headlights and taillights of passing cars as neon streaks. “ ese streaks of light are visualizations of the passage of time,” explains Wolf. “ is exhibition drives home the point that Jews have been a part of Cincinnati’s fabric since the very beginning,” says Schwartz. “It’s not about patting ourselves on the back. Every immigrant community has done extraordinary things in our city. Jewish Cincinnati is a reminder of that shared experience.”

In addition to his subjects’ compelling historical backgrounds, the aesthetic e ect of Wolf’s photographs is enhanced by subtle artistic decisions, says Schwartz. He sets most of his images against a twilight sky. e transitional state between day and night enhances the dreamlike e ect of merging the past and the present. Wolf’s deliberately slow shutter speed captures the headlights and taillights of passing cars as neon streaks. “ ese streaks of light are visualizations of the passage of time,” explains Wolf. “ is exhibition drives home the point that Jews have been a part of Cincinnati’s fabric since the very beginning,” says Schwartz. “It’s not about patting ourselves on the back. Every immigrant community has done extraordinary things in our city. Jewish Cincinnati is a reminder of that shared experience.”

Jewish Cincinnati: A Photographic Record runs through Jan. 29 at Jewish Cincinnati: A Photographic Record runs through Jan. 29 at Hebrew Union College’s Skirball Museum, 3101 Clifton Ave., Clifton. Hebrew Union College’s Skirball Museum, 3101 Clifton Ave., Clifton. Info: csm.huc.edu. Info: csm.huc.edu.

CULTURE CULTURE

A Timeless Town

A Timeless TownOur Town is every town in Xavier University’s latest production. Our Town is every town in Xavier University’s latest production.PREVIEW BY RICK PENDER

PREVIEW BY RICK PENDER

Casey Johnson as George and Mia Helbig as Emily in Our Town.

PHOTO:MAC MCDERMOTT Casey Johnson as George and Mia Helbig as Emily in Our Town.

PHOTO:MAC MCDERMOTT

In 1938, playwright ornton Wilder’s Our Town won the Pulitzer Prize for drama. Staged simply with almost no scenery but featuring a stage manager as a kindly narrator, gently guiding audiences through the action, it’s about the daily lives of two families as their children fall in love, marry and eventually die. e story is set in Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire, in the rst decade of the 20th century. But Wilder’s themes had a universality that continues to ring true today.

Nevertheless, one might ask if it’s a play that can advance the education of Xavier’s theater majors.

Stephen Skiles, director of Xavier’s theater program, tells CityBeat that Our Town’s themes are a good t with several campus organizations presenting “Spirituality and the Arts” events this fall. One of those will be a talk-back after an Our Town performance.

“We all go back to the pandemic,” Skiles points out. “ ere was so much loss, not only of life, but of time and connection and relationships. Our Town was in the back of my mind as I considered shows for this year. I read it one afternoon and before I knew it, I was crying. I was incredibly moved. It has a hopeful yet realistic side to it when it deals with some of these issues.”

He cites a speech by a young woman about how we too often miss out on the beauties of life.

“[ ings that are] right in front of us. at feels like a really important message for our students,” Skiles says. “It’s often in my mind – this story and these people. e simplicity of this story and these people — there’s a reason this play has stuck around. I really wanted students to participate in this story.”

Skiles sought out Aaron Rossini, a professional director and founder of New York City’s Fault Line eatre, to stage Our Town. At rst glance, Rossini — a graduate of Miami University — might seem an unusual choice, since his theater focuses on new plays. But Xavier has bene ted from Rossini and others from Fault Line who have come to campus to workshop new scripts, sometimes taking them to full productions.

“What is so compelling about Our Town is that its ubiquity is well earned. It connects simply and directly to American audiences,” Rossini tells CityBeat. “It does that ne dance between being saccharine and appropriately self-re ective and nostalgic. Our Town goes right up to the edge but never gets into the ‘Lifetime [or] Hallmark original-movie’ kind of thing. It’s grounded emotionally in a realistic space.”

Rossini has developed new plays while working with Xavier theater students, but this time around, Skiles suggested Our Town.

“I’m never going to do this play in my theater company. We are proud to do new plays, and it is meaningful to do that. But boy, oh, boy, do I love that show!” Rossini recalls thinking then. “We wanted to do something that would give students a lot of opportunities.” e size of the production’s cast provided some inspiration to Rossini, as well.

“Our Town has a big cast. When Stephen put that on the list, it lit up for me, because it’s not something I would normally give myself the opportunity to work on,” Rossini says. “It’s been a very long time since I’ve worked on a play where the writer was not sitting next to me.”

Asked what he’s doing to bring Our Town’s story out of a New England town and into the present at Xavier University in Cincinnati, Rossini says he envisions telling “the story of today using Wilder’s words from the past.” He says the play’s title implies not just the speci c New Hampshire setting,

but all the towns and locales where it’s produced. Rossini says he wants to nd ways to incorporate Xavier’s theater department into the design of the show. “We’re not going to change any words,” Rossini says. “We’re not going to alter the text to make it seem like conceptually we’re in a section of Cincinnati in the middle of campus. But I want the actors to think about their experiences in the world right now.” He says to do that, a set piece from a recent production might be leaning against a wall. “Is there something that feels like what happened last year at Xavier?” Rossini wonders. “Rather than making Grover’s Corners new, what do we have in our possession that can tell the ‘our town’ of the story – the ‘Xavier town’?” Rossini agrees with Skiles that Wilder’s play addresses issues that come up in everyday small town life. “I really want the students to think about the ways that global issues a ect them, personal issues, political issues. What does it mean to fall in love and get married and lose your wife at such a young age?” Rossini says. “Even if you’re doing a period piece – say, I n 1938, playwright ornton Wilder’s Our Town won the Pulitzer Prize for drama. Staged simply with Romeo and Juliet – it still has to be about right now. “Wilder has given us a very loose container to ll with the contempo-almost no scenery but featuring a stage rary world. at’s what I want to focus manager as a kindly narrator, gently on and that’s how I’ve interpreted the guiding audiences through the action, lines,” he continues.it’s about the daily lives of two families Staging shows within a college as their children fall in love, marry and theater program is also about training eventually die. young actors. Rossini says his goal is to e story is set in Grover’s Corners, teach students to rehearse a play with New Hampshire, in the rst decade of positive results. the 20th century. But Wilder’s themes “I want them to bring tools they’ve had a universality that continues to ring learned like script analysis, acting and true today. movement into our rehearsals and

Nevertheless, one might ask if it’s a make bold and brave choices that are play that can advance the education of based in what the author has o ered Xavier’s theater majors. in his text, so they can tell the story in a

Stephen Skiles, director of Xavier’s way that’s clear and theatrical and fun theater program, tells CityBeat that and repeatable,” Rossini says. “I treat Our Town’s themes are a good t with the students as professionals and show several campus organizations present- them how to successfully rehearse a ing “Spirituality and the Arts” events play.”this fall. One of those will be a talk-back Our Town is a powerful vehicle to after an Our Town performance. teach these lessons. Xavier’s cast of

“We all go back to the pandemic,” 15 young actors will gain meaningful Skiles points out. “ ere was so much experience while working on one of loss, not only of life, but of time and the great American plays. at’s what connection and relationships. Our theater education is all about. Town was in the back of my mind as I considered shows for this year. I read it one afternoon and before I knew it, I was crying. I was incredibly moved. It has a hopeful yet realistic side to it when it deals with some of these issues.” He cites a speech by a young woman about how we too often miss out on the beauties of life. “[ ings that are] right in front of us. at feels like a really important message for our students,” Skiles says. “It’s often in my mind – this story and these people. e simplicity of this story and these people — there’s a reason this play has stuck around. I really wanted students to participate in this story.” Skiles sought out Aaron Rossini, a professional director and founder of New York City’s Fault Line eatre, to stage Our Town. At rst glance, Rossini — a graduate of Miami University — might seem an unusual choice, since his theater focuses on new plays. But Xavier has bene ted from Rossini and others from Fault Line who have come to campus to workshop new scripts, sometimes taking them to full productions. “What is so compelling about Our Town is that its ubiquity is well earned. It connects simply and directly to American audiences,” Rossini tells CityBeat. “It does that ne dance between being saccharine and appropriately self-re ective and nostalgic. Our Town goes right up to the edge but never gets into the ‘Lifetime [or] Hallmark original-movie’ kind of thing. It’s grounded emotionally in a realistic space.” Rossini has developed new plays while working with Xavier theater students, but this time around, Skiles suggested Our Town. “I’m never going to do this play in my theater company. We are proud to do new plays, and it is meaningful to do that. But boy, oh, boy, do I love that show!” Rossini recalls thinking then. “We wanted to do something that would give students a lot of opportunities.” e size of the production’s cast provided some inspiration to Rossini, as well. “Our Town has a big cast. When Stephen put that on the list, it lit up for me, because it’s not something I would normally give myself the opportunity to work on,” Rossini says. “It’s been a very long time since I’ve worked on a play where the writer was not sitting next to me.” Asked what he’s doing to bring Our Town’s story out of a New England town and into the present at Xavier University in Cincinnati, Rossini says he envisions telling “the story of today using Wilder’s words from the past.” He says the play’s title implies not just the speci c New Hampshire setting, but all the towns and locales where it’s produced. Rossini says he wants to nd ways to incorporate Xavier’s theater department into the design of the show. “We’re not going to change any words,” Rossini says. “We’re not going to alter the text to make it seem like conceptually we’re in a section of Cincinnati in the middle of campus. But I want the actors to think about their experiences in the world right now.” He says to do that, a set piece from a recent production might be leaning against a wall. “Is there something that feels like what happened last year at Xavier?” Rossini wonders. “Rather than making Grover’s Corners new, what do we have in our possession that can tell the ‘our town’ of the story – the ‘Xavier town’?” Rossini agrees with Skiles that Wilder’s play addresses issues that come up in everyday small town life. “I really want the students to think about the ways that global issues a ect them, personal issues, political issues. What does it mean to fall in love and get married and lose your wife at such a young age?” Rossini says. “Even if you’re doing a period piece – say, Romeo and Juliet – it still has to be about right now. “Wilder has given us a very loose container to ll with the contemporary world. at’s what I want to focus on and that’s how I’ve interpreted the lines,” he continues. Staging shows within a college theater program is also about training young actors. Rossini says his goal is to teach students to rehearse a play with positive results. “I want them to bring tools they’ve learned like script analysis, acting and movement into our rehearsals and make bold and brave choices that are based in what the author has o ered in his text, so they can tell the story in a way that’s clear and theatrical and fun and repeatable,” Rossini says. “I treat the students as professionals and show them how to successfully rehearse a play.” Our Town is a powerful vehicle to teach these lessons. Xavier’s cast of 15 young actors will gain meaningful experience while working on one of the great American plays. at’s what theater education is all about.

Xavier University will present Xavier University will present Our Town Nov. 18-20 at the Gallagher Student Center eatre, 3800 Victory Pkwy., Evanston. Our Town Nov. 18-20 at the Gallagher Student Center eatre, 3800 Victory Pkwy., Evanston. Info: xavier.edu/theatre-program. Info: xavier.edu/theatre-program.