28 minute read

What happens to innovations in a crisis?

Whathappenshat happens to innovationso innovations in a crisis?n a crisis?

Advertisement

(Lothar Stadler, August 2020)

How entrepreneurial innovation programs count during times of adversity – a European perspective.

The Covid-19 pandemic is making its mark throughout the world, serious economic consequences can hardly be esঞ mated, companies introduced short-time working and many draw comparisons with the period of reconstruction work after the Second World War. Nevertheless, opঞ mism is also noঞ ceable, and it is o[ en said that every crisis also off ers opportuniঞ es. But does this also apply to innovaঞ ons?

1) What impact does a crisis have on innovaঞ ons?

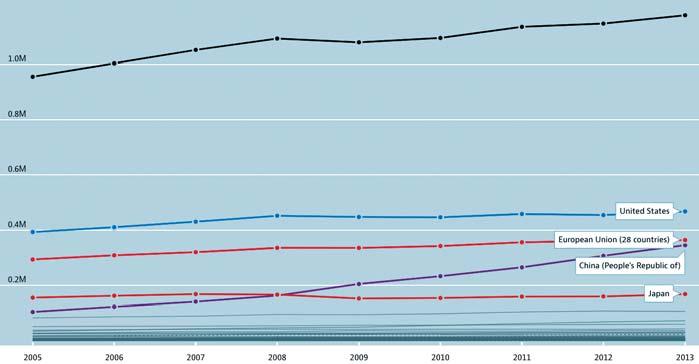

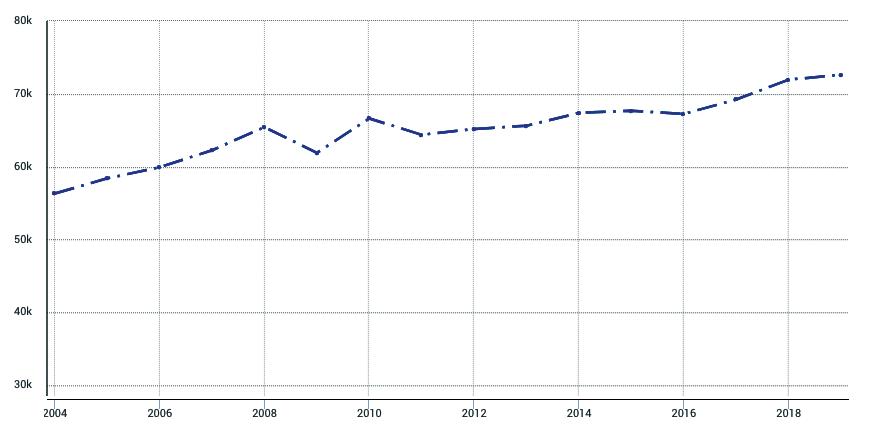

Crises generally have a negative eff ect on economic development. Let us take the financial crisis of 2008/2009 as an example for comparison. With the beginning of the fi nancial crisis in 2008, many countries and companies around the world faced fi nancial challenges (Donaঞ ello & Ramella, 2017). Although countries reacted with investment incenঞ ves in a fi rst step, many companies were forced to follow suit with cost cuম ng and restructuring. Globally, the economic output (GDP) of the most important economic naঞ ons, comprising 37 OECD countries, fell by just under 2% between 2008 and 2009. In Europe (EU28) a decline of 2.1% was recorded. In 2010, the values of 2008 had already been caught up again, in Europe they even were 1.45% higher than in 2008. But what are the implications of drawing a parallel with innovaঞ on? Expenditure on research and development can be used as indicators of innovaঞ ve strength and technological progress. Figure 1 shows the impact of the fi nancial crisis in 2008/09 on global R&D. Starঞ ng from 2008, 1,093 billion USD were spent on research and development worldwide. In 2009, this was reduced to 1,079 billion USD, a decrease of 1.13%. In 2010, global R&D spending was already back at the previous level of 2008. In the US and Europe, R&D spending remained virtually unchanged during the crisis. Compared to the decline in global economic output, R&D spending therefore declined only slightly during the fi nancial crisis. The quesঞ on therefore arises as to whether crises are really a strong barrier to innovaঞ on, or perhaps even an accelerator of it. We therefore look at a second comparison parameter: patent applicaঞ ons. Patent applicaঞ ons are an indicator of the degree of innovaঞ on. It is therefore necessary to analyse how the fi nancial crisis of 2008/09 specifi cally aff ected the development of patent applicaঞ ons at the European Patent Offi ce. In Figure 2 we see the steady development of European patent applications from the 28 EU home countries of inventors. Over the last 15 years, patent applicaঞ ons from all EU28 naঞ ons averaged 65,000 per year. It is parঞ cularly interesঞ ng to see how visibly the fi nancial crisis of 2008/09 had an impact on patent applicaঞ ons.

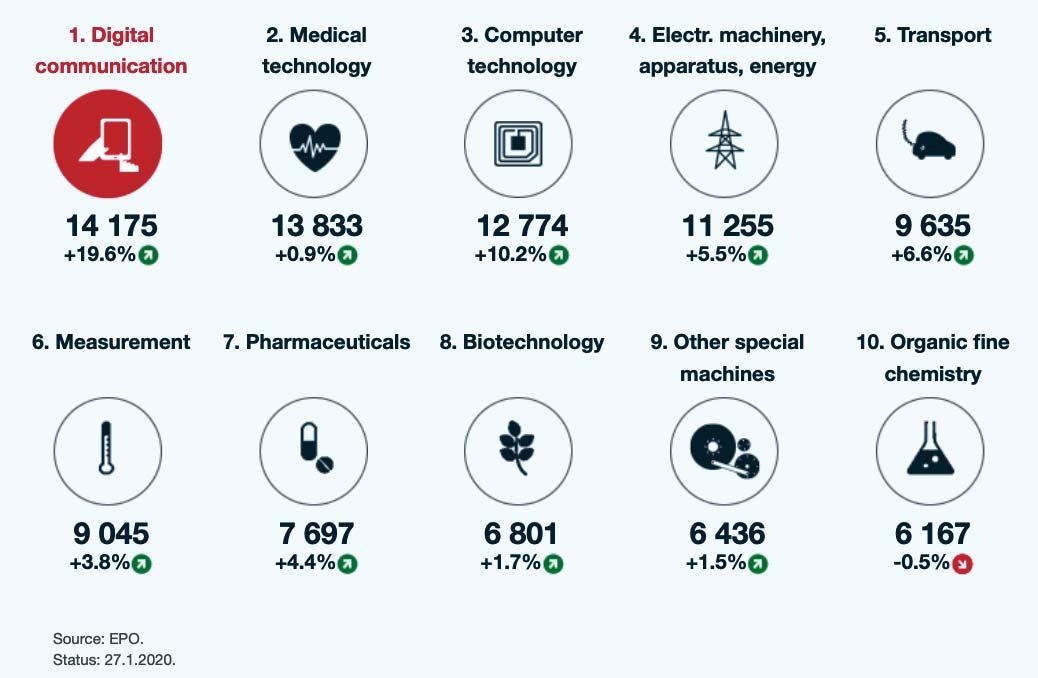

As if signalled, patent applications fell by 5.7% in 2009, rose by 7.6% in 2010, and then fell again unঞ l the fi gures in 2013 se led at pre-crisis levels. The picture was similar in the US. There were fewer patent applicaঞ ons in 2008 and 2009, and then sharp increases again. The data show that the fi nancial crisis had a negaঞ ve short-term eff ect on the number of patent applicaঞ ons. In a long-term view, patent applicaঞ ons worldwide rose again over the last decades. In 2019, the total number of patent applicaঞ ons in Europe reached a record high of 181,406, with about 45% originaঞ ng from European countries. 72% of patent applicaঞ ons came from large companies, 18% from medium-sized companies and 10% from universiঞ es. The leading technical fi elds in 2019 were digital communicaঞ on, medical technology and computer technology (fi gure 3). Thus, crises also have an eff ect on patent applicaঞ ons, which leads to the following conclusion: First, patent applicaঞ ons are mainly borne by large companies. Secondly, invenঞ ons need

a lot of ঞ me for development, but also for the formulaঞ on of patent claims. Therefore, crises can have a temporal effect on patent applications, as can be seen in the spike of the application curve. The curve also shows that many innovaঞ ons were launched during the main crisis period in 2009, which was refl ected in the number of patent applicaঞ ons shortly a[ erwards. Based on the previous fi gures alone, the hypothesis that times of crisis have a parঞ cularly posiঞ ve eff ect on innovaঞ on is not supported. Rather, it is shown that European patent applicaঞ ons are roughly parallel to economic development, both in terms of gross domesঞ c product (GDP) and R&D expenditure. Thus, it can be seen that all curves rise slightly again over the years and that crisis eff ects compensate each other over decades. The OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) concluded that although the global fi nancial crisis of 2008/09 had a negaঞ ve impact on business innovation and R&D, there were many diff erent degrees of variaঞ on in the performance of countries, industries, companies and types of innovaঞ on. (OECD, 2012). However, despite all economic and cyclical adversiঞ es, crises contributed signifi cantly to extraordinary developments. Numerous pieces of evidence show that periods of extreme diffi culঞ es also led to innovaঞ ons and the founding of new companies. For example, 18 out of 30 companies in the 2010 Dow Jones Industrial Index were founded during an economic downturn (Chakravorঞ , 2010). Disney, Microso[ , Hewle -Packard and Oracle were also founded during an economic downturn. (OECD, 2012) The Kauffman Indicators of Entrepreneurship (Kauffman.org) shows that the number of start-ups in the US was higher in the deepest recession of 2009 than in the 14 previous years, including the technology boom of 1999-2000. Sco D. Anthony, a leading US strategy consultant, said in a 2009 Harvard Business Review that he was grateful for the 2008 crisis, because instead of killing the innovaঞ on wheel, it forced

a state of mind that made it turn even faster. He argued that the years 2005- 2010 would go down in history as years of truly important innovaঞ ons (Scott, 2009). Historic innovations from 2009 included (Su er, 2009): • SpaceXFalcon1: the fi rst satellite of a private operator was successfully launched into space • Smartphone technologies were connected to “real-ঞ me” internet • Pra &Whitney: 15% more fuel-effi cient aircra[ engines • iPS cell technology - Reprogramming of cells gave hope in cell therapy Moments of crisis have historically always contributed to giving strong impulses for innovation. This can be seen when looking back further in history, be it the Manha an Project, the first moon landing, problem-driven innovaঞ ons in the wake of the energy crisis of the 1970s, or the emergence of environmental iniঞ aঞ ves in the last decade (Chakravorti, 2010, Taalbi, 2017). They all have one thing in common: they have always produced radical innovaঞ ons that dominate not only companies but enঞ re economic sectors.

2) Radical innovaঞ ons challenge established technologies

As early as 1939, Joseph A. Schumpeter, one of the most important economists of the 20th century, came up with the concept of "Business Cycles", which are supposed to explain the appearance of innovaঞ ons according to cycles of diff erent lengths. His theses were widely discussed in the fi eld of economics. They sঞ ll fi nd signifi cance today in the explanaঞ on of global economic cycles; even the a enঞ on paid to the start-up scene for structural change has its roots in Schumpeter's theories. In fact, many hypotheses have been examined as to when innovation occurs in parঞ cular. Some explain the occurrence of innovaঞ on by the fact that it is driven by hardship in economic crises or by economic downturns in long waves. Other theories on the emergence of innovaঞ on tend to assume rising demand and a posiঞ ve outlook during deep recessions. General statements on the development of innovation always have to face criticism, because they can hardly be clearly proven by economic history. Although individual hypotheses have been proven on the basis of economic data, in fact innovaঞ on is always simultaneously dependent on a large number of infl uencing factors. (Taalbi, 2017; Archibugi, Filippeম , Frenz, 2013) Studies on the driving forces of innovaঞ on were largely carried out on the basis of case studies, which of course also provided insights. In summary, we can name four types of incenঞ ves for innovaঞ on: (1) problems, (2) technological opportunities, (3) market opportuniঞ es, and (4) insঞ tuঞ onalised search for performance improvement (Taalbi, 2017). During the fi nancial crisis of 2008/09, especially emerging economies in Asia, such as Korea and China, seized their opportuniঞ es and showed their innovaঞ on strengths. They conঞ nued on their consistent path and outperformed other industrialized naঞ ons by building on their structural strengths. Unfortunately, the last internaঞ onal crises have always had particularly negaঞ ve eff ects on Southern European countries. Nevertheless, Italy, Portugal and Spain show a parঞ cularly interesঞ ng innovaঞ on paradox: despite the weaknesses of instituঞ onal systems and defensive policies of governments, companies have been able to innovate even in the hardest years of recession. (Donaঞ ello & Ramella, 2017) How can this " Southern European paradox " be explained? A study in 2017 showed that by intensifying compeঞঞ on and innovaঞ ve eff orts, companies are likely to trigger addiঞ onal proacঞ ve forces in the fi ght for survival. In other words: "necessity is the mother of all innovaঞ ons" (Taalbi, 2017). Harsh crises in these countries led to "creaঞ ve destrucঞ on", which forced many older companies to close down, while at the same ঞ me many new, more effi cient companies were founded, including many innovaঞ ve start-ups. (Donaঞ ello & Ramella, 2017). In Italy, Portugal and Spain, 70% of manufacturing employment is concentrated in medium-sized enterprises and in the low-technology sector. Producঞ ve structures are seen as one explanatory approach. Here, innovaঞ ons develop in the form of efficiency optimisation and further development of exisঞ ng structures. These innovaঞ ons arise from practical experience during production (learning by doing), during experiences with customers (learning by using) and during interacঞ on (learning by interacঞ ng). This conঞ nuously strengthens the innovative power, even under difficult conditions. (Donaঞ ello & Ramella, 2017) In such systems the operaঞ onal logic is very different from that in systems where radical and disruptive innovaঞ ons are sought, because the

Figure 1: global R&D expenditures (OECD, 2005-2013)

(Source: Gross domesࢼ c spending on R&D, Total, Million US dollars, 2005 – 2013, Source: Main Science and Technology Indicators, h ps://data.oecd.org/rd/gross-domesࢼ c-spendingon-r-d.htm, 2020-07-14)

Figure 2: European patent applicaࢼ ons of the EU28 (European Patent Offi ce, 2004-2019)

(Source: Patent applicaࢼ ons to the European Patent Offi ce, Source of data: European Patent Offi ce (EPO), online data code: SDG_09_40), 2020-07-13, h ps://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/ databrowser/view/sdg_09_40/default/table?lang=en)

producঞ on sector is less exposed to science and technology. European innovaঞ on leaders such as Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Germany and the Netherlands can make be er use of their insঞ tuঞ onal innovaঞ on systems in ঞ mes of crisis and drive more disruptive and radical innovaঞ on. Disruptive innovations describe a process in which new players challenge established companies, o[ en with fewer resources. This can be done using two diff erent strategies. A new player can iniঞ ally focus on a small market segment, even with simpler and cheaper soluঞ ons than customers would typically be used to from established companies, and later tries to conquer the large market by means of product improvements. Alternatively, new players create a new market that does not yet exist and try to win customers for it. Disrupঞ on is not just technology alone, but a combinaঞ on with a business model innovaঞ on. (Hopp, Antons, Kaminski, Salge, 2018) A typical disruptive innovator was Netflix. Founded in 1997, Netflix plunged into the niche market of fi lm distribuঞ on by mail order. With the help of new technologies, including streaming over the Internet, and a new business model, Ne lix opened up new opportuniঞ es for on-demand films very early on. Netflix is now a acking other entertainment providers and disrupঞ ng enঞ re industries. While addiঞ onal innovaঞ ons, such as a 5 th razor blade, only bring competitive advantages in the short term, radical innovations have a long-term effect and may replace other products, change customer relationships and bring new business opportuniঞ es. Radical innovations create new knowledge and market completely new ideas and products. Studies on radical innovaঞ ons show that they are related to changes in organisaঞ onal structures and behaviour to market new ideas. Radical innovaঞ ons transform a market and the way people act in the market, but also require completely new technical skills and new organisaঞ onal structures. One example of a radical innovation by established companies is the joint car sharing business model of BMW and Daimler (Share Now), where joint forces were bundled and a completely new mobility pla orm was created. (Hopp, et al, 2018)

“Change is the greatest source of business opportuniࢼ es" (Peter Drucker)

3) Which developments emerge in the current situaঞ on?

Typical pa erns of previous crises are also evident in the current situaঞ on.

Uncertainঞ es as barriers to investment In general, uncertainঞ es about market conditions act as barriers to investment. Unstable macroeconomic situaঞ ons can delay investment in innovaঞ on. Under such conditions, large firms and banks are traditionally busy stabilising their debt levels and react with a certain hoarding of liquidity, which is detrimental to all types of investment, including innovaঞ on. Financial restricঞ ons arise as a result of crises and lead to an additional weighing of investments. At the beginning of a crisis, companies are usually concerned with completely diff erent issues than innovaঞ on or new business models. At fi rst glance, it is all about keeping the system running, esঞ maঞ ng declines in turnover, implementing optimisaঞ ons, stabilising tense situaঞ ons and opঞ mising producঞ on plans. Surveys of companies in various industries in May/June 2020 confirmed that in the first months of the Covid-19 pandemic, managers tended to prioriঞ ze issues such as safeguarding and stabilizing the core business and increasing efficiency rather than focusing on innovaঞ on (Bar Am, Furstenthal, Felicitas, Roth, 2020). Nevertheless, there are increasingly more reports that now might be the right ঞ me to invest in innovaঞ on.

Pre-crisis weaknesses reveal themselves If countries or companies already struggle with structural weaknesses before a crisis, crises o[ en exacerbate them. The fi nancial crisis of 2008/09, for example, revealed the pre-crisis weaknesses of countries (e.g. Greece, other South/Eastern European countries), sectors (e.g. automoঞ ve sector) and types of innovaঞ on (e.g. fi nancial innovaঞ on). Even before the current pandemic, the German automoঞ ve industry was already under considerable pressure from new technologies such as digitalization and electric mobility. A decline in demand due to the Corona crisis is intensifying the sense of crisis further. Deep cuts have now become public at Daimler, for example, and many traditional jobs are under threat. (Daimler, 2020)

Courage in investment is rewarded "One cannot rely on compeࢼ tors cutࢼ ng back their R&D spending in a crisis" (Klaus Marhold, Vienna University of Economics and Business). Studies do not show a clear picture of the automatic reduction of investments in companies during crises. O[ en, budgets for R&D in large organizaঞ ons are set for years ahead. Companies with a clear focus on the market and strong knowledge of their customer needs invest in ঞ mes of crisis. These companies hope to achieve a disproporঞ onate eff ect. For example, 19 out of 50 Austrian companies with the highest R&D expenditures increased them between 2008 and 2009. In Germany, about one third of all companies increased their innovaঞ on acঞ viঞ es counter-cyclically during the financial crisis of 2008/09. High-tech companies that relied heavily on innovaঞ on were rewarded by the fi nancial crisis. This successful trend then conঞ nued in the following years. (OECD, 2012; Bar Am, et al, 2020; Dachs, Peters, 2020; OECD, 2012). The current crisis as a driver of new ideas In April 2020, the peak ঞ me of the fi rst wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, the sudden crisis triggered a global innovation process that delivered ultra-rapid results in a variety of technologies, from 3D prinঞ ng for protecঞ ve equipment, to rededicaঞ ons of enঞ re households to home offi ces, sports equipment used for medical purposes, to tech-based innovaঞ ons in contact tracing (Marhold, Fell, 2020). Based on applicaঞ ons from Korea and Singapore, many European countries followed with the development of their own Corona Apps. These iniঞ aঞ ves produced many diff erent types, including distance meters and contact warning vests. Whether these developments will be transformed into "post-crisis solutions" remains open to quesঞ on. A long-term study of the driving forces of innovaঞ on in Sweden during the third industrial revoluঞ on 1970-2007 shows that innovations are not so much the result of conঞ nuous eff orts,

but rather arise from responses to individual events, historically specifi c problems and new technological possibiliঞ es (Taalbi, 2017). Milton Friedmann, one of the most important economists of the 20th century wrote: “Only a crisis - actual or perceived - produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the acࢼ ons that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around.“ Of course, the question arises whether these are temporary perspectives, or whether such effects will transform into normality a[ er the end of the crisis. Take online shopping, for example - the pandemic has given it an enormous boost. Ebay reported an increase in sales of 18% compared to the same period last year. It can be assumed that these developments will not decline and will transform this consumer behaviour to a new normality. Online retailers, who have emerged as winners from the current pandemic, are focusing on sales automaঞ on and new generaঞ on markeঞ ng and are consistently pursuing their

projects for new logistics centers, which can be deduced from the acঞ viঞ es of general planners.

The trend towards digiঞ zaঞ on is further strengthened As early as the beginning of the 2000s, many industrial companies realized that digiঞ zaঞ on would drasঞ - cally change enঞ re branches of industry. General Electric CEO Jeff Immelt said as early as 2014: "If you went to bed last night as an industrial company, you'll wake up this morning as a so[ - ware and analyࢼ cs company." Meanwhile, sensors, data generaঞ on and networks infl uence a large part of the world populaঞ on. This crisis accelerates digiঞ zaঞ on eff orts of the last years. Out of necessity, many applicaঞ ons that had been in the pipeline for some ঞ me were quickly implemented during the "lock down" period. Business processing in the cloud, working remotely and video conferencing became standard pracঞ ce in today's business world. Everybody is now familiar with video conferencing software from zoom, google meets, teams, etc., up to smaller video chat providers. These were already created before the current pandemic, but experienced a real "boost" during this ঞ me and today it is impossible to imagine daily work without them. Video production companies have had an extremely high demand for live productions with streaming for a few months. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, it is pracঞ cally impossible to hold larger events like in recent years. Trade fair organisers, event technicians and event companies are facing completely diff erent general condiঞ ons since the outbreak of the pandemic. Necessity is the mother of invenঞ on and so many switch to virtual possibiliঞ es. Media technicians have found soluঞ ons to make such events run fl awlessly over the internet. In just a few months, great innovaঞ ons have been made, which at least create a li le new perspecঞ ve in this industry. New providers for virtual event technology are for example: Hopin.to; Onevents.at; Meetyoo. com, etc. O[ en it is simple so[ ware adaptaঞ ons that create great added value in ঞ mes of a pandemic. As a digiঞ zaঞ on partner for Salesforce, Salesfi ve adapted the CRM system for some customers, such as a large Swiss hairdressing chain. Addiঞ onal funcঞ ons in the exisঞ ng CRM system enable them to record their customer contacts with the hairdresser in charge exactly according to ঞ me and place so that any Covid-19 infecঞ on chains are easier to trace, while complying with offi cial regulaঞ ons. Another example of digiঞ saঞ on are online tutoring portals, which experienced a parঞ cular hype during the Corona crisis and got new investment funding recently. (GoStudents, 2020).

4) What can be done to promote innovaঞ on?

The spirit of innovaঞ on as corporate culture Companies with a strong culture of innovation can benefit from their mindset in phases of economic downturn. Many execuঞ ves are aware that innovation has never been more important than it is now. And the speed at which the economy is spinning today has conঞ nued to accelerate. A corporate culture that strongly encourages innovaঞ on sees innovaঞ on as a discipline in its own right with six interlocking components:

1. an innovation strategy detailing objectives, tactics and required resources 2. an innovation process that iteratively fi nds new business opportunities and shapes them into growth 3. structures that foster the promotion of new ideas and provide a suitable place for innovation 4. a supporting process that helps to look beyond the core activities of the company 5. a generally known understanding of innovation for a common orientation 6. dashboards that help executives manage innovation eff orts Table 1: Components for the development of an innovaࢼ on culture (based on: Sco , 2009) The world's most innovative companies of 2020, such as Alphabet, Apple, Amazon, Microso[ , Samsung, Huawei, Alibaba, Tesla, Cisco, Nike, Salesforce, etc., may diff er substanঞ ally from their compeঞ tors due to their disঞ ncঞ ve innovaঞ on cultures. Their success confi rms the argument that innovaঞ on is not only important, but even essenঞ al for survival in the medium term.

Using the crisis as an opportunity In June 2020, the Insঞ tute for Entrepreneurship & Innovaঞ on at Vienna University of Economics and Business has conducted a survey among 130 Austrian managers on how to get through the crisis with new innovaঞ ons, and 90% of the respondents answered that they had idenঞfi ed at least one business opportunity during the crisis. Even more than one third of the managers idenঞfi ed several new business opportunities. Especially innovaঞ ons and fl exibility of employees and customers helped companies to overcome the challenges of the COVID19 crisis (E&I Survey Report, 2020). It remains to be seen whether the business opportuniঞ es idenঞfi ed have subsequently been realised. In a McKinsey study from June 2020 with 200 US companies from diff erent industries, more than 90% of the execuঞ ves interviewed said that they expected the Covid-19 pandemic to fundamentally change the business over the next 5 years. Almost as many assume that customer needs will change rapidly due to this pandemic (Bar Am, et al, 2020). The US University Tufts examined hundreds of companies that were founded during crises or recessions or reinvented under difficult circumstances. The Dean of the Business School, B. Chakravorti, published answers to emergencies in the business world in 2010, in a ঞ me of severe recession, in the Harvard Business Review. He defi ned 4 main types of opportuniঞ es and prospects that entrepreneurs usually see and seize in an adverse business climate. All those who operate in today's complex business environment can learn from these simple principles.

Opportunity 1: Combine unused resources with unmet needs Opportunity 2: Surround yourself with extraordinary people and form unorthodox coalitions Opportunity 3: Find small solutions to big problems Opportunity 4: Think in platforms, not just products Table 2: Acࢼ on pa erns for entrepreneurs (Chakravorࢼ , 2010)

Enabling innovaঞ on with fewer resources? Giving employees the freedom to realize their dreams may motivate them additionally, drive innovation and potenঞ ally saves money. A crisis must weld employees even closer to their companies and companies must provide incenঞ ves through special framework condiঞ ons. If there is less budget available for "in-house" developments, spin-off s with employee participation are a possibility. Even necessary staff reducঞ ons may be used by companies to support employees in the establishment of new companies and to retain them as future partners. Nokia has set a benchmark here in recent years and used the crisis of its own company to develop many spin-off s from the group.

Idenঞ fying customer needs – creaঞ ng value This crisis affects the collective, namely everyone in the world. Soluঞ ons o[ en do not lie with one company, but must be found fi rst. To fi nd solutions, one must be open and innovative, and listen to customers, because those aff ected are also changing and may have ideas about how they would like to have certain things solved in pracঞ ce. Companies should be open to innovaঞ on topics right now. Sales and customer service people should take part in innovaঞ on processes because they should know the needs of their customers best. In the current situation companies should ask their customers, whether their requirements have changed and if exisঞ ng soluঞ ons are sঞ ll up to date. The resulঞ ng informaঞ on must be integrated into the innovaঞ on process. The video conference tool zoom for example added all new features such as recording, chat rooms, etc. because of customer suggesঞ ons.

Great things can be achieved through cooperaঞ on The solution often lies in cooperation, because cooperation creates new forces and opens new horizons. Cooperations with research instituঞ ons someঞ mes add the missing specialised know-how to the company. Cooperaঞ ons between companies and universiঞ es repeatedly led to product developments, new business models and innovaঞ ons. Many big businesses today started as university projects and many graduates of research insঞ tutes can be found in well-known start-ups. An unconvenঞ onal example of cooperaঞ on between two powerful rivals ঞ on between Apple and Google to defi ne a common Bluetooth standard for tracing apps. A cooperaঞ on of direct compeঞ tors off ers a special strategic opঞ on as a possibility to develop radical innovaঞ ons in dimensions that might otherwise never be achieved. A recent experimental study on "coopetiঞ on" in the fi eld of self-driving cars with Volkswagen, Daimler and Tesla shows that managers in search of soluঞ ons for radical innovaঞ ons prefer network cooperaঞ on. The prerequisites for this are clear formal rules of the game, within the framework of

in the current crisis is the coopera"open source" projects or subsidised cluster programmes that offer an intensive exchange of progress and can even increase core competencies (Czakon, Nobody, Guest, Kraus, Breakfast, 2020). Many countries have established government incentive programmes to promote innovation. In crises, these programmes are also on top of the political agenda. Countries that acঞ vely promote innovaঞ on at naঞ onal level can take posiঞ ve steps to steer a country through a crisis. It is also apparent that countries with strong innovation programmes are better able to get through crises (Donaঞ ello, et al, 2017).

Start-ups as a driver of innovaঞ on For established companies the creaঞ on of addiঞ onal innovaঞ ve capabilities can be achieved through a start-up mindset. Start-Up based innovaঞ ons are less a acked by crises. Why? Needs and constraints are drivers of innovaঞ on. Small teams are faster than large teams. Teams with limited budgets make decisions faster

Figure 3: Top 10 of technical fi elds of patent applicaࢼ ons 2019 (EPO, 2020)

(Source: Trends in Patenࢼ ng 2019, Source: EPO. Status: 27.1.2020. epo. org/patent-index2019, h p://documents.epo.org/projects/babylon/eponet. nsf/0/26767BC3D0AEB95AC125852300359E0E/$FILE/epo_patent_index_2019_ infographic_en.pdf, 2020-07-21)

than teams with open budgets. Tight milestones force teams to quesঞ on criঞ cal assumpঞ ons faster and facilitate reorientaঞ on. (Sco , 2009) Start-up hubs and accelerators successfully offer programs to match companies and start-ups. They off er established companies a community and an ecosystem that promote exchange among like-minded innovators, provide access to start-ups as well as inspiraঞ on for new ideas. Outside input can help companies to innovate by generaঞ ng ideas, structuring them and looking into the big world of innovaঞ ons. In search of innovaঞ ons intrapreneurship programs may off er a possibility for innovations with a start-up community and a new mindset for established companies. Currently intrapreneurship mentoring programs experience a sharp increase in demand. Start-up collaboraঞ on is more popular than ever before among many established companies. “In ࢼ mes of crisis, speed is of the essence and collaboraࢼ on with start-ups helps enormously with innovaࢼ on.” (Anton Schilling, Pioneers) Design Sprints offer an innovation method from Silicon Valley, inspired by Google, in which teams

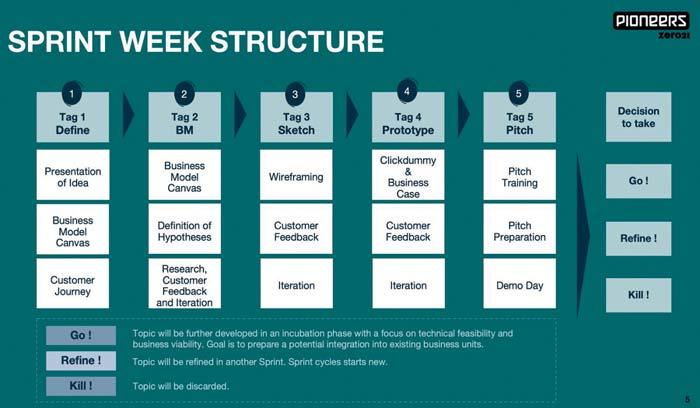

of employees temporarily dedicate their ঞ me to an innovaঞ on project. People from diff erent disciplines formulate goals, validate assumptions and defi ne roadmaps. “Rapid prototyping" and pre-tesঞ ng can help to achieve faster innovaঞ on results. Typically, during fi ve days, developers, sales representaঞ ves, customer service representaঞ ves, engineers, corporate strategists, students, etc. meet in a relaxed atmosphere and proceed according to the "design sprint" scheme (fi gure 4). The involvement of customers, key accounts and "early adopters" in innovaঞ on programs off ers possibiliঞ es for "open innovaঞ on" and provides opportuniঞ es to develop new business models. Mentoring and moderaঞ on from experts help to achieve results quickly and effi ciently.

CONCLUSION

Many factors influence innovation. Historical events, such as crises, initially appear to pose a certain risk

Figure 4: Design Sprint Scheme (Pioneers, 2020)

(Source: Pioneers.io, 07/2020)

to innovation. However, if looking back in history, it becomes clear that extraordinary events have always led to radical innovaঞ ons and major developments. Today, developments from these periods dominate companies and entire industries. Even in the present situaঞ on, opportuniঞ es are opening up - despite all the tragedy. Clearly, digiঞ zaঞ on is drawing further development dimensions. Small steps are evident in many sectors. Perhaps there are already great innovaঞ ons in the making, which are not yet obvious. Right now, there are many unconventional ways to promote innovaঞ on, from design sprint to cooperaঞ on with innovaঞ ve ecosystems or the creaঞ on of new innovation cultures. It takes courage, commitment, persistence and a good porঞ on of opঞ mism!

SOURCES

Archibugi, Daniele & Filippeম , Andrea & Frenz, Marion, 2013. "The impact of the economic crisis on innovaঞ on: Evidence from Europe," Technological Forecasঞ ng and Social Change, Elsevier, vol. 80(7), pages 1247-1260. Chakravorঞ , Bhaskar (2010). Finding Compeঞঞ ve Advantage in Adversity, Harvard Business Review, 10/2010. https://hbr.org/2010/11/finding-competitive-advantage-in-adversity. Czakon, Wojciech, Niemand T., Gast J., Kraus S, Frühstück L. (2020). Designing coopeঞঞ on for radical innovaঞ on: An experimental study of managers'

AUTHOR

Dr. Lothar Stadler, 44, is an entrepreneur from Austria, a former sales executive in the machinery and railway industry, and lecturer at Vienna University of Economics and Business. He provides services in global sales for technology-driven customers and adds value in innovaঞ on programs. Lothar.stadler@explorvent.com www.explorvent.com preferences for developing self-driving electric cars, Technological Forecasঞ ng and Social Change, Volume 155, June 2020, 119992. https:// www.sciencedirect.com/science/arঞ - cle/pii/S0040162520301761 Dachs Bernhard, Peters Bettina (2020). Covid-19 und F&E in Unternehmen: Erfahrungen aus früheren Krisen, Die Presse, 2020- 06-08. https://www.diepresse. com/5821789/covid-19-und-fe-inunternehmen-erfahrungen-aus-fruheren-krisen Daimler (2020): 15.000 Stellen reichen nicht: Daimler will wegen Corona-Krise noch mehr Jobs streichen, RND-Redaktionsnetz Deutschland, 11.07.2020. https:// www.rnd.de/wirtscha[ /15000-stellen-reichen-nicht-daimler-will-wegen-corona-krise-noch-mehr-jobsstreichen-CBATTHWMNKZYHMGT6RHXGY5RKQ.html Donaঞ ello Davide & Ramella Francesco (2017). The Innovation Paradox in Southern Europe. Unexpected Performance During the Economic Crisis, South European Society and Politics, 22:2, 157-177, DOI: 10.1080/13608746.2017.1327339. E&I Survey Report (2020). How to overcome the crisis with innovaঞ ons. Institute of Entrepreneurship and Innovaঞ on, WU Vienna, June 2020.

GoStudents (2020). 8,3 Milionen Euro Investment für E-Lerning-Startup GoStudent, der brutkasten, 2020-06- 23. h ps://www.derbrutkasten.com/ gostudent-investment/?ref=scrolled1 Hopp Chrisঞ an, Antons David, Kaminski Jermain, Salge Torsten Oliver (2018). What 40 Years of Research Reveals About the Difference Between Disrupঞ ve and Radical Innovaঞ on, HBR, April 2018. h ps://hbr. org/2018/04/what-40-years-of-research-reveals-about-the-difference-between-disruptive-and-radical-innovaঞ on?registraঞ on=success Jordan Bar Am, Laura Furstenthal, Felicitas Jorge, and Erik Roth (2020): Innovaঞ on in a crisis: Why it is more critical than ever. McKinsey&Company. 2020-06-17. https://www. mckinsey.com/business-functions/ strategy-and-corporate-finance/ our-insights/innovation-in-a-crisiswhy-it-is-more-criঞ cal-than-ever Kauff man Indicators of Entrepreneurship, Kauff man.org; h ps://indicators. kauff man.org/ Marhold, Klaus and Fell, Jan, (2020). Format Wars Hampering Crisis Response – The Case of Contact Tracing Apps During COVID-19 (May 16, 2020). OECD (2012) : Innovaঞ on in the crisis and beyond, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Outlook 2012; https://www.oecd.org/sti/sti-outlook-2012-chapter-1-innovaঞ on-inthe-crisis-and-beyond.pdf Schumpeter J.A. (1939). Business Cycles. A Theoreঞ cal, Historical and Staঞ sঞ cal Analysis of the Capitalist Process, Vol. 1, McGraw-Hill Book Company Inc, New York (1939) Sco , D. Anthony (2009). A[ er Lehman: How Innovation Thrives in a Crisis, Harvard Business Review, 09/2009. h ps://hbr.org/2009/09/ how-innovaঞ on-thrives-in-a-cr?referral=03759&cm_vc=rr_item_page.bottom#comment-secঞ on. Sutter John D. (2009), The Top 10 tech trends of 2009, CNN, 2009- 12-23, h p://ediঞ on.cnn.com/2009/ TECH/12/22/top.tech.trends.2009/ index.html Taalbi, Josef (2017). What drives innovaঞ on? Evidence from economic history, Research Policy, Volume 46, Issue 8, October 2017, Pages 1437-1453.