art culture inspiration EVOKATION

2O24 ISSUE

An Evoke Contemporary publication

2O24 ISSUE

An Evoke Contemporary publication

Santa Fe is bustling with summer activities and artistic energy! The gallery’s Summer Salon promises a vibrant showcase of diverse artworks, complemented by a series of engaging events such as artist talks, studio visits, and demonstrations. This creates an excellent opportunity for art enthusiasts to connect with the artists, understand their creative processes, and gain insight into their inspirations.

Moreover, the achievements of several artists are being highlighted across various museums in New Mexico this year. Thomas Vigil and Patrick McGrath Muñiz are featured in the exhibition The Ugly History of Beautiful Things at the Nuevo Mexicano Heritage Art Museum in Santa Fe. Esha Chiocchio’s photography can be viewed at the Roswell Museum as part of the group show Regenerative Actions. Irene Hardwicke Olivieri and Patrick McGrath Muñiz are showcased in Vivarium: Exploring Intersections of Art, Storytelling, and the Resilience of the Living World at the Albuquerque Museum. Additionally, Nicholas Herrera’s artwork is part of Common Ground: Art in New Mexico at the Albuquerque Museum, leading up to a major solo exhibition at the Harwood Museum in Taos this fall, followed by another solo exhibition at Evoke.

For those interested in art and culture, Santa Fe and its surrounding areas seem to be the place to be this summer. Whether attending exhibitions at the gallery or exploring the museum shows across the state, there’s plenty to celebrate and appreciate about the artistic community in New Mexico.

Kathrine Erickson + Elan Varshay Owners and Publishers

Michael Abatemarco is a freelance writer and amateur photographer with a passion for New Mexico’s culture and history. He lives in Santa Fe.

Mara Christian Harris is a marketing and communications professional. She has been associated with Evoke since its inception.

Kelly Koepke is a freelance arts, culture and food writer who loves talking to smart people about what they are smart about.

Richard Lehnert is a poet, music critic, and freelance copyeditor who for 40 years has edited arts copy for many New Mexico publications. After 30 years in Santa Fe, he now lives in Ashland, Oregon.

Staci Golar is an arts and culture writer who has had the privilege of sharing creative people's stories in publications across the US.

Emily Van Cleve is a Santa Fe-based freelance writer whose articles have appeared in local, regional and national magazines.

Calendar of events 4 The Fate of Poetry: Alice Leora Briggs

8 Summer Salon: group exhibition & events

16 Honey in the Desert: Irene Hardwicke Olivieri

22 Pasión: Nicholas Herrera

28 Inscapes and the Persistence of Nature: David T. Alexander

32 Curators We Love: Jana Gottshalk

EVOKATION is published by Evoke Contemporary, 550 S. Guadalupe St., Santa Fe, NM 87501.

© EVOKE Contemporary. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

On the cover: Kent Williams, Hike Through Bailey Canyon (detail), oil on clayboard,36" x 36".

All events take place at Evoke Contemporary, 550 S. Guadalupe Street, Santa Fe, NM 87501. Visit evokecontemporary.com to sign up for special previews and for further information.

Jun 28 TheFateofPoetry | Alice Leora Briggs

An exhibition suggesting that the foundation of art, like that of poetry, continues despite death, despite endings.

On display through July 20, 2024.

Jun 28 SummerSalon,PartI | Group Exhibition

A two-part show with an emphasis on the artwork of Patrick McGrath Muñiz.

On display through July 20, 2024.

Jul 26 Summer Salon, Part II | Group Exhibition

Introducing paintings by Jeremy Miranda who seeks the magic and beauty of the moment in everyday life.

On display through August 24, 2024.

Aug 3 Artist Demonstration | Thomas Vigil reveals his unique technique using discarded street signs, aerosols and stencils combined with the Catholic religious iconography that permeates Hispanic culture.

1pm Saturday, August 3, 2024.

Aug 17 Artist Talk | Esha Chiocchio uses her combined knowledge of visual storytelling, anthropology, and sustainable communities to weave narra-tives about land, culture, and climate solutions. 1pm Saturday, August 17, 2024.

Aug 24 Artist Demonstration | Kristine Poole presents her sensitive approach to the human form in clay contrasting classically rendered figures with contemporary motifs and surface treatments.

1pm Saturday, August 17, 2024.

Aug 30 Honey in the Desert | Irene Hardwicke Olivieri

An exploration of an ongoing theme of rewilding the heart, exploring connections to wild animals, wild lands.

On display through September 21, 2024.

Aug 31 Artist Talk | Irene Hardwicke Olivieri will be giving a talk on her creative process; what sparks ideas; and the life experiences that feed her imagination.

1pm Saturday, August 31, 2024.

Sep 27 Pasión | Nicholas Herrera

Pasión explores the finality of death and the brutality and heartbreak of war and oppression, with a good dose of current politics. On display through October 19, 2024.

Oct 25 Inscapes and the Persistence of Nature

David T. Alexander’s exuberant, layered brushstrokes packed with color are part of this artist’s constant dialogue with the natural world in this solo exhibition focusing on the remote high desert regions of New Mexico. On display through November 23, 2024.

“The fate of poetry is to fall in love with the world, in spite of History,” said poet and playwright Derek Walcott (1930–2017) in his 1992 Nobel Laureate Lecture. The same words emblazon The Fate of Poetry, a mixed-media work by artist Alice Leora Briggs, bisecting the vertical composition into a dark, claustrophobic bottom half and a light-filled upper portion. Below, human skeletal remains sprawl motionless in a grave. Above, two skeletal feet dangle over the grave.

History is rife with endings. In The Fate of Poetry, a combination of acrylic painting and sgraffito, Briggs suggests that the foundation of art, like that of poetry, continues despite death, despite endings. And while everyone who walks above the world’s cemeteries inevitably meets the same fate, still they persist in their attempts to indelibly imprint themselves on history.

“What Walcott meant, and what I mean by using his phrase, is that everything inevitably breaks, unravels, falls to pieces: our bodies,

our cultures—and someday, no doubt, the entire world,” Briggs says. “But we’re always in the process of trying to glue things back together. To paraphrase [art critic] Dave Hickey, any attempts to reconstitute the past are akin to reassembling a branch thrown through a woodchipper.”

This understanding of the futility of re-creating the past— especially as, of course, we are always working with incomplete knowledge—is not intended to be bleak. We select from the past, from memories, and create new meanings, new narratives.

After a hand-painted ceramic tile made by her daughter shattered on the floor, Briggs reassembled it. “It was a little bit askew and a little less complete,” she says, “but it contained a great deal more love than when it was intact and taken for granted.”

The Fate of Poetry is also the title of Briggs’s June exhibition at Evoke Contemporary, which uses words and imagery to explore death as reality and as metaphor. Massacre of the Innocents, for instance, makes references to several mass killings, including the 1994 Rwandan Genocide; the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School mass shooting, in Newtown, Connecticut; and the 2022 Robb Elementary School shooting, in Uvalde, Texas. While some words and phrases inscribed on the text-filled composition appear to be from news reports relating to these bloodbaths, others are musings by the artist, who contrasts the slaughter of innocent schoolchildren with her own mother’s 101st birthday, suggesting a bitter irony.

Briggs is known for works that comprise provocative amalgams of classical and contemporary imagery that illuminate the narcotictrade–driven violence of Ciudad Juárez. Her new work includes more recent images that “are an examination of my own history and that, hopefully, manifest some larger meaning.”

Briggs now cares for her elderly mother, who is cognitively impaired. “I’m in strange territory now,” the artist says. “Instead of Mexico, I’m in ‘Dementia’. But my work has always been about mortality. That’s the overarching theme.”

Briggs was born in West Texas and grew up in Idaho’s Snake River Valley. A Fulbright Scholar and a 2020 Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellow, she now has work in major collections, including the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, in Bentonville, Arkansas; the Library of Congress; Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library; and the de Young Museum, in San Francisco.

Sgraffito, her main medium, was a popular art form in Europe with roots in antiquity. Briggs often works in large scale (La Familia,

a triptych, is 17 by 62 inches) on wood panels reinforced with crossbraces. She scratches into panels prepared with layers of rabbit-skin glue or acrylic, kaolin clay, and a binder. The surface is then airbrushed with India ink. This creates a dark ground with light-colored clay beneath, which is revealed by incisions and ablations made using scalpels, X-Acto knives, sandpaper, steel wool, and other tools.

Unlike other forms of drawing, which are additive, Briggs’s process is subtractive, or rather extractive, which seems ideal for her themes of mortality and history. Images are revealed as in an archeological dig and are rendered with fine detail. Take the hairs and musculature of the hapless, chained dogs in La Familia. Their fur billows and undulates, the subtle contrasts of light and shadow created by careful mixes of faint and heavy scratches.

The imagery, which includes many direct and indirect references to death, is not intended to convey a dour view of the world. Even in the case of searing, challenging works such as Massacre of the Innocents, the choice of subject questions, surveys, and seeks some point, some meaning, amid futility.

In the grand tradition of art—and poetry—it seeks meaning in the patently absurd while evoking compassion and hope—and perhaps even change.

Despite the guns, the bones, and the piled corpses, tossed from a cliff in acts of genocide—or, taking a cue from Walcott, despite History—a continuum stretches from art history’s ancient past to its present. Memento mori—reminders of mortality—are reflected in the mirror so that actions on our side of it might be

meaningful, even worthwhile. Still, we’ll be mindful of each life’s impermanence.

“What an amazing gift this is,” marvels Briggs—“to be able to breathe, make work about this, and make some attempt to communicate it to other people.”

—Michael Abatemarco

Evoke celebrates summer with a two-part group show featuring 25 artists over a two month period. In addition to the exhibitions in the galleries, watch for a series of artist talks, demonstrations, and studio visits throughout the season. This two-part series headlines with the compelling and symbolic work of Patrick McGrath Muñiz and in follows with the introduction of the paintings of Jeremy Miranda focused on beauty in daily life.

Artist Patrick McGrath Muñiz’s library of figures and symbols is filled with images from Spanish Colonial iconography, American pop culture, and tarot, as well as personal myths and symbols. While much of his painting practice is based on Renaissance and Baroque traditions, he’s also very tuned in to contemporary culture. Finding ways to bring past and present together in new and exciting ways is a driving force in his work.

Born in Puerto Rico and educated there, in San Juan, and at Savannah College of Art and Design, in Georgia, Muñiz now lives in Texas. The paintings that materialize in his Houston studio reflect his passion for exploring questions both existential and earthly. What makes us human? Muñiz asks himself. Where are we going as a species?

In Muñiz’s latest body of work, exhibited in Evoke’s Summer Salon, human vulnerability is front and center. Most of the paintings feature the nudes that have been part of his art practice since the 1990s. “Nudes are the perfect emblematic image representing vulnerability and exposure,” he says. “They break down to the essence of humanity.”

Muñiz’s nudes are presented in environments rich in imagery. In the painting Mystical Graces, which features the Three Graces, the artist seems to wonder what these women, whom he’s surrounded with bits and pieces of modern culture—books, a television, a can that appears to be leaking oil, etc.—are telling us about our world today.

While women regularly appear in his works—Muñiz grew up with a mother but not a father—men show up more often in his latest pieces. “Now that I am a father”—Muñiz has a six-year-old son—“I am becoming the archetype that was absent in my life,” he explains. “A father figure is very important.”

The only painting in Summer Salon that does not feature nudes is La Barca de los Creyentes (The Ship of the Believers). In this work depicting men, women, children, and animals on a small boat in the middle of a large body of water, Muñiz ponders the ideas of belonging to a community and feeling stranded. Hovering in the sky about their heads are three figures: a pagan goddess, the Virgin Mary, and a UFO. It’s not unusual for Muñiz to combine such disparate images in one work. “I always think about what imagery is meaningful to me,” he says. “The challenge I face is balancing personal symbols with universal ones. Sometimes I find myself working with images that are very personal to me, and realize I need to make changes so the images are more accessible.”

Although there is a serious aspect to his work, Muñiz is aware that his paintings include satire and sarcasm, even if they’re not readily apparent to the viewer. “I’m hiding, concealing, and revealing, all at the same time,” he says. “At the heart of my practice, I make art as a way to know myself, and to connect my own story with the larger story of humanity.”

Be aware in the present. Notice the magic and beauty of the moment. These are Jeremy Miranda’s painting mantras. A graduate of the Massachusetts College of Art and a native of Rhode Island who now lives in Maine, with his wife and two children, Miranda finds in daily life unlimited inspiration for his paintings. The works he exhibits in Evoke’s Summer Salon are interior environments and exterior scenes close to home.

“I’m finding beauty in everything,” says Miranda, whose latest pieces include images of a pot of boiling water and a simple wooden table with two chairs. One work in the show captures sunset light on a potted indoor plant. “It was my daughter’s bedtime, and she asked me to find her stuffed animal,” he recalls. “I walked downstairs and saw evening light coming through the window and illuminating the plant. It was so beautiful. I took a photo of it before I went back upstairs to tuck my daughter into bed.”

Miranda never travels far from home to find his subjects. Instead, he portrays interior and exterior scenes within a five-mile radius of his studio. “I couldn’t paint a place I visit,” he says. “I need to feel a connection to a place. When I do, I start to see the whole universe there. Then I can drift into a kind of cosmic existence when I paint.”

Most days begin with an informal meditation practice: an hourlong session during which Miranda creates a small sketch. Then, when it comes time to paint, he takes great joy in building up layers and adding glazes so that the work feels handmade. To sidestep decision fatigue, he intentionally limits his color palette. “I struggle with controlling color,” he explains. “I may not even start with three primary colors. I purposely give myself a tight palette, and pull as much variation out of it as possible.”

While there may be a story behind a painting, that’s not what captivates Miranda, who is primarily interested in slowing down, taking the time to notice the world around him. “I want to see the world hidden from plain sight,” he says. Although his paintings are completely devoid of humans, evidence of their existence is apparent. “I’ve never been interested in painting the figure,” he says. “I’m fixated on the idea of being alone in the moment.”

In retrospect, Miranda feels his earlier work was driven in part by his ego. Since the birth of his first child, eight years ago, he’s been more committed to allowing the painting process to happen, and then seeing what emerges on panel or canvas. Painting has become a practice of being loose and aware, and watching the movement of the paint. That practice feels most alive when the painter occupies this space.

“I always want my paintings to feel that they’ve been created with excitement,” he says. “Rather than focus on whether a painting is good or not, I want it to come from a place of fascination and joy. For me, paintings are full of mystery.”

—Emily Van Cleve

Lee Price creates realistic oil paintings, that show women and food in their intimate and private settings. The pictures are female subjects, getting excessive with food that is considered indulgent, forbidden, or comforting. Her works addresses the intersections of food with body image, addiction, and unabating desire.

Brian Rego combines imagination and memory with the sense of sight and components from the observable world to make his paintings. As he works directly from life and in the studio, his paintings result in the accumulation of personal experience and narrative that embody themselves as symbols of his interior world.

An innate desire to channel nature’s magnificence lay at the center of McElwain’s work. Through thick, heady strokes of luminous pigments, she managed to build a connection among physical, spiritual, and external forces in two dimensions.

Javier Marín conceives an integral human being through analyzing the construction and deconstruction process of threedimensional forms. To achieve his objective, he works with photography, textile, graphics, drawing and sculpture. Although many of his pieces are paradoxically abstract, he is mostly known for his figurative sculpture.

KENT WILLIAMS

Kent Williams puts forth bold realism with combined attributes of abstraction and neo-expressionistic sensibilities. His work is characterized by strong gestural forms combined with areas of layered and arresting detail, rendered with rich dynamic brushwork.

HARRIET YALE RUSSELL

Harriet Yale Russell’s geologically inspired, thickly textured abstract paintings present an exciting exploration of shape and line in an energetic, yet sophisticated color palette.

1 PM Saturday, August 3

Santero and stencil artist Thomas Vigil will give a demonstration of his process: how a template is developed, sketched over, cut and recut for each layer of paint used on an artwork.

At conception, an idea is hundreds of hours away from the birth of an image; sketching, cutting, evaluating, and testing—each step needing multiple and minute adjustments. Vigil’s precise layering and meticulous blending are only done with aerosols, over stencils and freehand. And true to street art techniques, wheat paste, stickers and markers complete the work.

1 PM Saturday, August 17

Please join multimedia artist Esha Chiocchio and Reunity Resources Program Director Juliana Ciano for a discussion about regenerative agriculture, land restoration, and the importance of storytelling to elevate the efforts of those who are revitalizing our most precious resource: soil. Chiocchio will discuss her gilded aerial prints of a landrestoration project near the Lordsburg Playa and share a short video about Reunity Resources. Ciano will give an update on the farm's many activities, followed by a discussion about the intersection of land and art.

Gugger Petter’s works embody a balance of tensions beyond the loom on which she weaves. Her woven paper tapestries hover between opposites: control and chaos, light and dark, the everyday and the historical.

The artwok of Andrew Shears centers on his unconventional experiences with the mundane. Through beguilingly simple subject matter primitively centralized in composition, the work emanates wholeness.

1 PM Saturday, August 24

Kristine Poole will be doing an exclusive demonstration at Evoke in which she’ll show techniques for designing and sculpting the elaborate hairstyles that are a hallmark of her fired clay sculptures. As the hair design often relates to the words, she’ll also demonstrate how she chooses and inscribes patterns and text on her figures.

1 PM Saturday, August 31

Irene will be giving a talk on her creative process; what sparks ideas and the life experiences that feed her imagination. She grew up in the borderlands of south Texas and Tamaulipas Mexico; her childhood years were spent along the Rio Grande River . These early experiences in the natural world surrounded by rich diversity of cultures lit the way for the rest of her life.

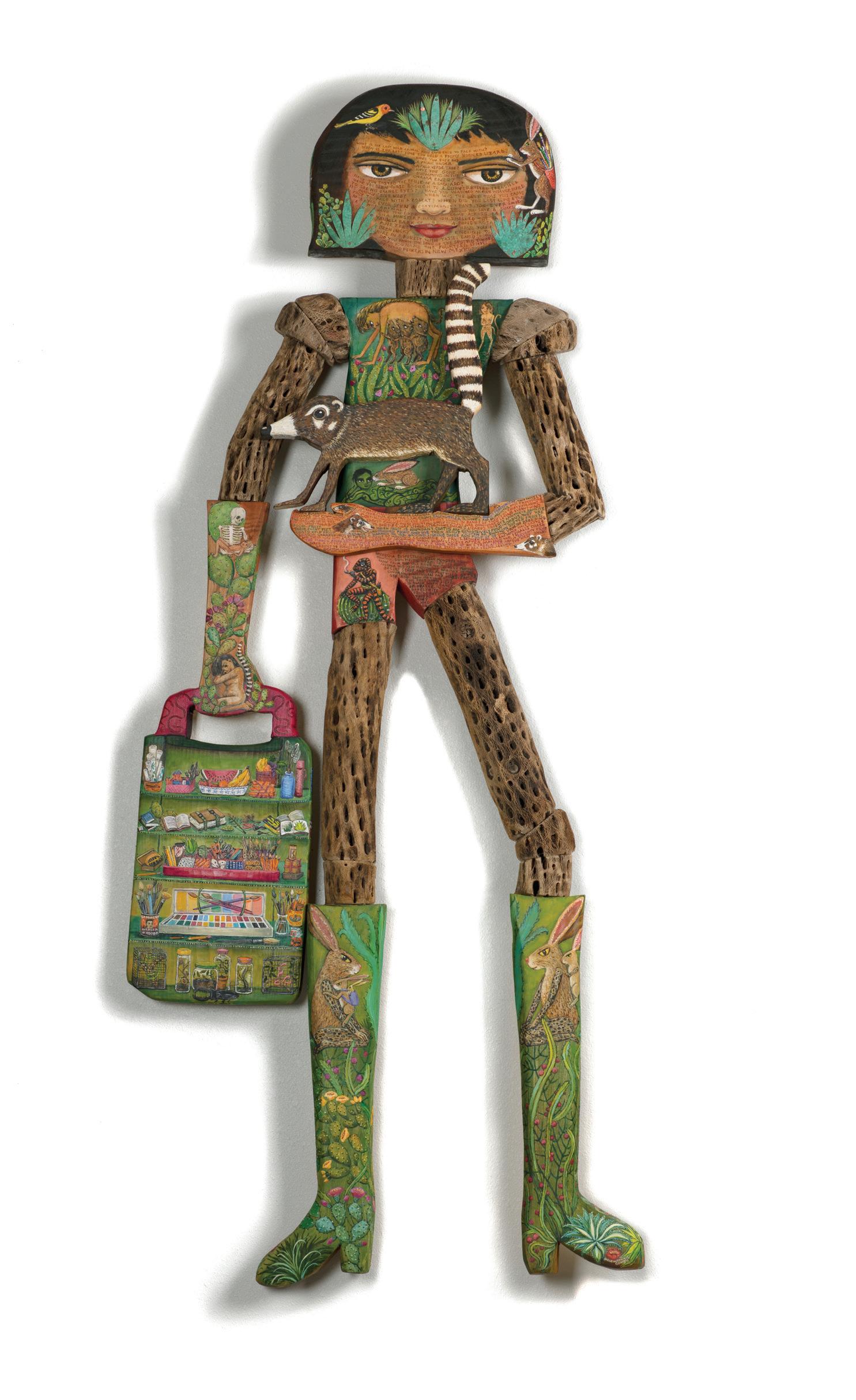

Irene Hardwicke Olivieri presents her recent work, introducing her multidimensional cholla figures alongside her paintings and drawings in a solo exhibition comprising 25 works of art.

The cholla is a cactus family of more than 35 species, all characterized by a hardwood-like skeletal structure and cylindrical stems sprouting abundant spines. “I love cholla!” said Olivieri. “Each species has such interesting characteristics, and provides food and shelter to a variety of birds and animals. I love how they demand their own space in the desert.” She has honored this nurturing plant by incorporating its skeletal remains into her most recent works. Starting with the New Mexican cane or tree cholla (Cylindropuntia imbricata) found in the Santa Fe area, she quickly realized that its small size was limiting her; she then ventured into Arizona’s Sonoran Desert to gather the skeletons of the thicker teddy-bear or jumping cholla (Cylinropuntia bigeloveii). This allowed her to construct large-scale sculptural figures, along with giving her the pleasure of hiking through nature to harvest dead cholla, and being surprised by glimpses of the horned lizards, rattlesnakes, javelinas, and other desert creatures that inspire her work.“When I find a cholla that is skeletonized,” Olivieri explained, “they still have some thorns on them—sometimes they’re completely covered in spines. Using a variety of saws and rasps, I scrape off the thorns, then bring them home, where I sand them with an electric pad sander until they’re very smooth.”

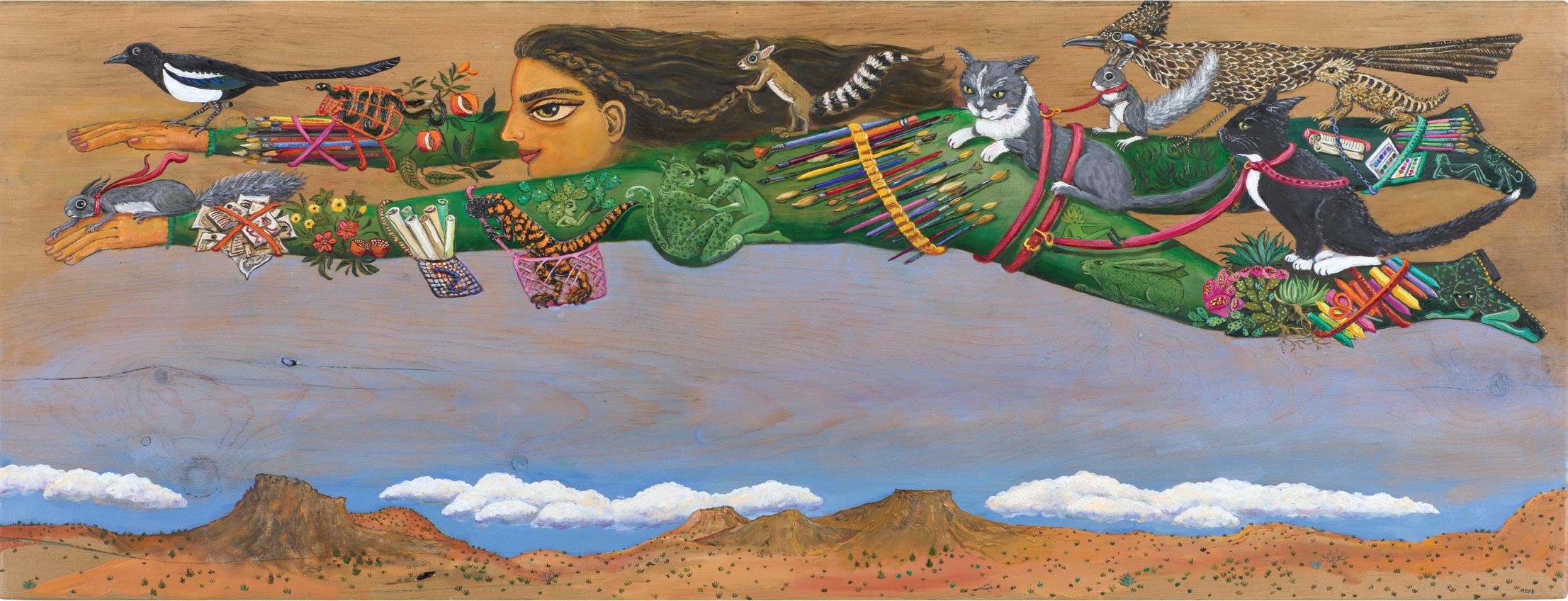

The creative process of working with cholla wood has introduced Olivieri to entirely new tools and media, and brought to her work a new excitement. In addition, there are times when the creativity of making art works in both directions, as in the case of Teporingo and Zacatuche, her painting of a jackrabbit making other creatures. Olivieri found that painting the jackrabbit doing what she wished to do enabled her to do the same—a thrilling discovery.

“My cousin is a kinkajou features an intrepid desert girl with a pet coati in one hand; in the girl’s other hand is a special satchel filled with everything needed to explore the desert: fresh fruit, plant press, collecting jars, books, sketchpads, pencils, paints, and brushes. Her shoulders are strong in their teddy-bear cholla shapes, and her cholla legs are powerful—as are her painted ponderosa-pine boots.

“The title is being spoken by the coatimundi the girl is holding. Coatimundi are in the family Procyonidae, along with ringtails, cacomistles, raccoons, and kinkajous. When we lived in Arizona we often saw coatimundi while hiking in Madera Canyon, and here, in the nearby Sangre de Cristo Mountains, we see ringtails on our trail camera.”

Olivieri said that making art is how she reacts to being alive. When she first encountered a spotted skunk, she couldn’t contain her excitement and researched all she could about the animal. She immediately made a painting about the skunks, thinking that in some way anyone who learns about them would be happier because of it. This continued with the artist’s introductions to the Gila monster, the rubber boa, the packrat. She feels astonishment and love for each new living creature she discovers.

Olivieri also finds inspiration for paintings in relationships. She has found painting to be healing in helping her to navigate challenging times in her life, and that her paintings help with sadness and difficulty. For example, she feels she was able to survive her father’s illness by painting about it. “My work is about so many different things—forever rewilding the heart, exploring connections to wild animals, wild lands. But I’m always painting about love, relationships, and obsessions, parts of life that are

often subterranean. My work portrays secret worlds of sensuality, emotional autopsies, and unexpected explorations of mortality.” The largest painting in Honey in the Desert is Secrets of the Neighborhood, which was inspired by true stories of some of Olivieri’s idiosyncratic neighbors in places she’s lived. The central figure was inspired by a neighbor who told Olivieri that she frequently walked her dog in the middle of the night down their road wearing nothing but her bedroom slippers. Olivieri was surprised, and couldn’t stop picturing her pale nude body as she walked her little white dog in the moonlight. Another neighbor told her of an incubus who visited her regularly in her bedroom. The artist loved this neighbor’s spotted dachshund, and couldn’t stop thinking of the poor dog anxiously watching this mysterious scene. And when Olivieri lived in the Oregon wilderness, a neighbor there built of juniper a gigantic chair that he would sit in naked.

“Another painting I’m still working on and have not yet named depicts a woman wearing a backpack filled with a collection of art supplies and staring defiantly at her own skeleton as water rises around them, symbolizing the passing of time. On my studio wall is a line from a poem by Rilke: ‘Is not impermanence the very fragrance of our days?’

“I keep a picture of me when I was eight years old on my studio wall,” Olivieri continued. “We are always still that eight-year-old kid, and seeing the little me every day reminds me not to let her down. I like thinking of the scope of our lives, from when we were a kid leaping forward to our future skeleton. What would my skeleton ask me? ‘Are you doing what you really want to do in this life? Do you owe someone an apology? Are you making the most of every day . . . ?’

“Thinking that the clock is ticking actually enlivens me, fills me with excitement for each day that I get to be alive. Making the most of every day, appreciating every beetle, bobcat, jackrabbit, roadrunner—every cactus, every thunderstorm—everything!

“I got the idea for the painting Favorite Neighbors in response to comments I’ve received from people at past shows, who let me know that some of the subjects I choose to paint—such as centipedes, packrats, snakes—are not very desirable. Why not paint more appealing animals?

“I paint what I love. I never think about whether or not someone else will like it. But as I look around my house, I see that those are the paintings that don’t always sell. Which is okay, because I love them—it makes me happy to have the packrat and spotted skunk in my living room. One day, I thought, Well, who would like those paintings and want to live with them?

Of course, it would be the animals who are in the paintings. So I decided to paint an apartment building where each floor has a family—one is the skunks, and a tiny version of my skunk painting is on the wall, and the skunks are at the dinner table nearby. Another floor is the packrats, then the javelinas, the vultures, the snakes, etc. The first floor is the art studio for the building. A Gila monster is painting a centipede girl, and a snake man is doing a self portrait.”

About the words that often adorn her paintings, Olivieri said, “The tiny painted lettering enlivens my paintings as it trails across the surfaces, creating new patterns and textures, sometimes questioning the viewer or sharing unusual details about some fascinating creature—or a miniature description, such as how to grow agave from seed. Wherever I go, I like to study and observe the flora and fauna, and draw and write about it in my sketchbooks. Sometimes these writings find their way into my paintings. I don’t expect the viewer to read the text in my art, but if they do, they just might thank me—because all of it is interesting, and might spark a new relationship with a wild animal or reptile that they might not have considered before, or maybe offer a different way to think about something they are experiencing.”

One of the biggest influences in Olivieri’s life was growing up in the borderlands of south Texas and the Mexican state of Tamaulipas. Her father was a farmer, and much of her childhood was spent along the Río Grande. This early experience of the natural world, surrounded by a rich diversity of cultures, set the course for the rest of her life. After living in nature—in Latin America, central Mexico, Austin, central Oregon, Maine, and for the last five years in Santa Fe—Olivieri is dedicated to supporting wildlifeconservation organizations. A percentage of the proceeds from Honey in the Desert will be donated to the New Mexico Wildlife Center and the Northern Jaguar Project.

In addition to Honey in the Desert, Irene Hardwicke Olivieri’s work can be viewed in the Albuquerque Museum of Art’s exhibition Vivarium: Exploring Intersections of Art, Storytelling, and the Resilience of the Living World. June 22, 2024–February 9, 2025.

A trail of pickup trucks piled high with timber winds down a mountain road—firewood for heating residents’ homes come winter. A farmer slops new mud on his old horno oven, as his ancestors have done for centuries. A rusted metal heart containing horseshoes, gears, and nuts and bolts of all sizes, all welded together to represent that organ’s hidden inner workings. A line of penitentes (penitents) make their way to church to be blessed.

Such are the images Nicholas Herrera creates in his self-taught, almost primitive style in his studio on ancestral land in El Rito, about an hour north of Santa Fe. Life in these remote northern New Mexico villages, their yearly secular and religious rituals, and the often-harsh realities of life generally—all are woven into his works.

Herrera’s show at Evoke, Pasión (Passion), opens September 27, featuring dozens of these and other brightly colored paintings and metal sculptures, each in some way expressing the idea of passion—whether interpreted as intense emotion, or as represented by a capital letter P for the Passion, the suffering and death of Jesus Christ, a frequent subject of Herrera’s works.

“To do something real, like a good piece of art, the passion comes out,” he says. “And that’s what makes the piece more. It’s like my mom and my dad used to say: from one bad thing, a lot of good things come out of it. So, that’s the way I see my life. A lot of bad things happened when I was younger, and they changed me. They made my art stronger. And I’ve never really followed other artists. I follow my instincts and my passion.”

The bad things Herrera has experienced range from alcohol and drug abuse to incarceration, violence, and, in his mid-twenties, a car accident that put him in a coma for weeks. That wreck, and the subsequent jail time for the reckless driving that caused it, are what he says turned his life around.

“I landed in jail in Los Alamos,” he says. “That’s where I met this guard who liked the sketches I was doing and trading him for cigarettes. He said his wife, who was an art curator, had seen the sketches and wanted to give me a show when I got out. So something good came out of almost dying.”

Since then, Herrera has become one of the country’s most renowned folk artists, carving retablos and bultos, painting santos in his throwback style, and experimenting with metal sculpture. He rode the late-1980s and early-1990s wave of outsider art with exhibitions around the country. He’s been honored with many awards, and his work is part of many museum collections,

including the Museum of American Folk Art, in New York City, and the Museum of International Folk Art, in Santa Fe. His most famous piece, Protect and Serve, portrays Jesus Christ in the back of a police car, and is part of the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. In September, the Harwood Museum, in Taos, will mount a retrospective of his artwork comprising some fifty pieces.

A 15th-generation New Mexican, Herrera grew up surrounded by the religious art and historic Spanish-colonial influences of his community. Using natural pigments, found items, and an ingenuity bred from having to create, maintain, and fix everything using only the few resources and options of his isolated village, in each of his pieces Herrera explores traditional Catholic beliefs, Native American spirituality, and his Sephardic, crypto-Jewish ancestry. All of this is mixed in with the challenging, uncomfortable circumstances faced by communities such as El Rito: lack of opportunity, poverty, drug use, and violence.

Herrera’s Pasión explores the finality of death and the brutality and heartbreak of war and oppression, with a good dose of current politics. That’s what’s on his mind right now.

“You know, there’s like a little thing telling me, Well, this is a good idea,” he says of his creativity. “I haven’t planned it. But all of a sudden, it’s like, wow! All of a sudden it comes to me. It just

kind of rattled around in my brain for a while, then it comes out fully formed as an idea and, you know, exactly what it’s going to look like. And then you make it.”

When asked in what direction his passions are taking him today, he shrugs and clenches his gnarled hands, calloused from welding, carving, and working around the farm and on the fifty acres of his

family’s land in the mountains. A touch of carpal-tunnel syndrome in his arms makes them numb. That, and age—he turned 60 in July—have made him contemplative.

“Given my age, I don’t have to work as hard to do a painting,” he says. “Sometimes you gotta go where you can save your health. If I was carving every day, I think my hands would be screwed, right? And metalwork and welding are also physically hard. But I think I have to do what I’m doing. Because it’s in me, and the ideas have to come out. Maybe I’ll start writing about art. But what do I want to say about art? It’s a beautiful thing to be an artist. It’s a hard thing. It’s like you’re giving part of your

life away. Your soul, right? Because you don’t have a retirement, you don’t get much Social Security, you know. You got to learn to budget yourself, you got to learn to invest for when you’re older.”

Wherever Herrera’s passions may take him, don’t underestimate him. Others have, to their consternation. “Some artists were all laughing at me when I did Jesus in the back of the cop car. It was just a weird, crazy piece. Whatever. And now it’s in the Smithsonian.” He laughs. “Well, those people are probably kicking themselves, I think.”

In addition to the show at Evoke, Pasión, opening September 27, Herrera is the subject of a one-man exhibition at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos. Nicholas Herrera: El Rito Santero runs September 21,2024–June 1, 2025.

How do you distill the energy of endless seas and skies, monumental mountains and deserts, into something more tangible? This is what Canadian painter David T. Alexander has endeavored to do throughout most of his career. Whether on imposing canvases spanning several feet or in pieces that can be held in two hands, his exuberant, layered brushstrokes packed with color are part of this artist’s constant dialogue with the natural world.

Born in Vancouver, British Columbia, Alexander seemed destined to be an artist. His grandmother and mother were both painters, and his mother knew Emily Carr, a Canadian painter—in her childhood, Alexander’s mother often visited the famed painter’s studio. “I was kind of fearful of her,” she admits, “but I loved her work.” After pursuing art at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, where he graduated with an MFA, he began a career that has taken him around the world for research trips, exhibitions, and prestigious artist residencies, including a stay at the Morris Graves Foundation, in California; Icelandic Artist Residency; Helene Wurlitzer Foundation Residency in Taos, NM; and another at Grand Canyon National Park. In 2018 Alexander was inducted into the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, the oldest national body of artists in Canada. His work can be found in important public, private, and corporate collections throughout the world, including the Museum of London, the Vancouver Art Gallery, the HBC Global Art Collection, NYC, and embassies in Berlin, Beijing, and Krakow.

While Alexander has now come full circle, returning after some 50 years to live and work near the wild sea and evergreen forests of the coastal region of Western Canada, in British Columbia, he continues to feel drawn to scenery that offers stark contrasts with what’s just outside his door. It’s part of his ongoing examination and documentation of places that require a bit of a journey to get to, that feel less marked by the constant buzz of civilization.

Much of Alexander’s latest work is inspired by his recent explorations of New Mexico, a state he first visited in 1996 and felt immediately drawn to. “I instantly fell in love with the desert,” he recalls. “I don’t know why, but I feel extremely comfortable there. . . . Visually, I find it astounding.” He says this new work is “an amalgamation of where I’ve hiked, driven through, walked over, looked at, and thought about that is so different than where I live.” Some pieces show dramatic shifts between mesas and buttes, rock and sky; others depict land patterned with sage and juniper. Many reference areas that left him quietly awestruck. “At one point last fall 2023, I couldn’t even talk about the landscape I was looking at because it was so different than what I’ve experienced there many times. But I’m always looking for that experience—it’s got to be there for me.”

The landmarks of interest in this body of work signify his endeavor to depict the dynamics between land and water. The more casual viewer might be surprised that several of Alexander’s current paintings—landscapes that clearly reflect the rich earth tones and iconic vistas of the arid Southwest—are actually astute observations of water in the desert. A closer look reveals that the element’s relationship and interaction with land is, as Alexander says, “basically a reflection of anywhere.”

Alexander draws on site and in his studio as a reference, and takes photos of places he visits time and time again, until he feels satisfied with what he understands of an area. Back in his studio, he refers to those images while using brushes, trowels, sponges, and other tools to push, pull, and even extract paint, until his reimaginings of the layers of soil, rock, and color eventually emerge. And just as time, erosion, and water constantly transform the surfaces of the earth, Alexander repeatedly changes and exaggerates the shapes, textures, and energy of the land with brushstrokes and paint.

“When it rains in the desert, the top layer of pigment in the soil gets washed down and runs over the other colors by gravity, like a brush veil of color from the top distributes the color to the bottom, ” Alexander explains, remembering a time when he saw the ochres, grays, and whites of a New Mexico cliff stacked atop one another, changing as it mixes with the color beneath. “That’s a thrill,” he says—“and it’s not just the way it looks, but the way it feels in my experience. Somehow, those experiences get connected, and along with those connections come the oddities of a landscape. It is the dynamics and formats of the painting itself which creates an understanding of the land and culture. Things such as the crust of a hot land’s pigment are like colors of chiles,

maize in unique shapes created by erosion. These things are what helped me create images of a land in flux.”

Each time Alexander puts pencil to paper or brush to canvas, the end result contains a degree of that type of experience. It’s become an almost daily ceremony of endless reexamination and contemplation, he says, of “being in a place over and over and over, until I don’t need to look anymore. I can honestly say I go to bed and I dream about making art, I wake up and I make more art. I can’t stop. The inquiry is never-ending.”

The institution formerly called the Museum of Spanish Colonial Art has taken a new path under a new name: the Nuevo Mexicano Heritage Arts Museum (NMHA). Why the change? “The old name no longer represented the depth of our collection,” says curator Jana Gottshalk. “The collection represents so much more than ‘Spanish’ or ‘Colonial,’ and that name factors out indigenous voices—and now contemporary voices—that have built New Mexico. There’s a reason for each word in the new name.”

Originally from Maine, Gottshalk came to the former College of Santa Fe in 2000 to study painting. After school, she found a job in the development department at El Rancho de las Golondrinas, in Santa Fe, doing everything from producing spreadsheets to working with volunteers to making tortillas at the event-based living history museum. She eventually became its assistant

curator, overseeing, among other things, the update of the museum’s DOS-based database to a more current system—as she describes it, “from the 17th century to the 21st!”

After that, she worked for five years as a curatorial assistant in the New World Department of the Denver Art Museum. “I loved working in a big museum. Constantly changing exhibitions and new interpretations of preColumbian and colonial art—along with fashion and contemporary exhibitions—kept things fresh.”

Gottshalk then returned to New Mexico to get a master’s degree in art history from UNM, studying colonial and WPA art (1935-1943). Her thesis work took her to archives all over the state. “I love archives,” she says. “It’s a treasure hunt, and grounds everything we do in fact.”

After graduate school, Gottshalk worked at the Museum

of Spanish Colonial Art (MOSCA), the New Mexico State Archives, and the New Mexico Museum of Art, returning to MOSCA in 2022 to assume the role of curator of the museum. “The new name is an opportunity to reexamine what it means to be a curator. We examine the voices we’re using, what communities we’re talking to—many of the exhibition labels are written by the artists themselves. We’re tapping into our archives to use original sources to pull original quotes on historic objects. Here we have a historic collection along with a lot of contemporary stuff, which is great, because it’s hard to talk about the new without talking about the old, and vice versa.”

Though other regions are represented, the NMHA’s collection primarily comprises the work of artists from New Mexico. “It’s more interesting to describe what’s currently going on here in the context of history and what’s going on elsewhere,” says Gottshalk.

Gottshalk describes her curatorial role as being both storyteller and project manager, coordinating artworks and artists’ voices, and allowing their works to play off each other. “We want to use primary sources, grounded in fact, as opposed to a top-down approach with curator as “expert”. Dialogue and education bring understanding, and we need to be open to that. It’s hard work, but we have to have it, here and at all museums, I think. We can have a concept for an exhibition, but be open to changing it as archival evidence or different voices dictate it. It’s like a scientific

hypothesis, or writing a thesis—you start out with one idea, but sometimes have to go back and change the thesis.”

The museum no longer runs the Traditional Spanish Market, but it still has a role in helping regional youth learn about their art and culture. “They learn their contribution is important to the overall conversation,” says Gottshalk. “Mentoring and education are so important, and we support a number of programs to tap the cultural knowledge of families.” A case in point is the current exhibit The Lowrider Bike Club: stunning examples of lowrider bicycles created by young people in collaboration with mentors, law enforcement, community leaders, and others. “You can really see the throughline from mentors to the youth, even as the collaborations introduce contemporary imagery and concepts,” says Gottshalk. “Also, it’s badass art!”

Going forward, the Nuevo Mexicano Heritage Arts Museum will work to increase its educational programs and make its library and archives more accessible, using more primary sources as part of the exhibitions. “It’s an amazing collection here, with so many stories to tell, that makes me want to stay here and in New Mexico,” says Gottshalk. “It’s an exciting moment.”

—Mara Christian Harris