73 minute read

Sports: A conversation with NBA Medical

Sub-Continent Society” because he had befriended students of Indian and Pakistani descent in Ewald who said, “‘Hey, come out [to one of our meetings].’ And I did.”

“I was so raw with where I was, I was just an open book to new experiences,” he recalls.

He also rose to the challenges the Academy presented. A notion of using spring track as a means to stay in shape for basketball was rewarded with a humbling 400-meter tryout lap that ended with a gassed Sims lying supine at the fnish line. Sims says Big Red track and feld coach Hillary Coder Hall dared him to measure up to his potential.

“She said, ‘You’re fast, and if you decide to take this sport seriously, you can do very well. But you have to decide if this is something you want to take seriously,’” says Sims, who calls the conversation one of the defning moments of his two years at Exeter. “She was basically telling me, ‘You can’t just do this on talent. There’s a lot of talent around here. You need to show up, be disciplined, and you need to be ready.’ And I took that to heart.”

The faculty recognized Sims’ commitment to his Exeter experience on graduation day, giving him the Warren Burke Shepard ’84 Award, which rewards a student who “tries hardest to realize the Exeter opportunity.”

“I knew I had been given a gift, and I had to take advantage of that gift,” he says.

STANFORD, PERIOD

As open as Sims was to possibilities at Exeter, his college choice was less negotiable. He had fxated on Stanford University since boyhood when a 1988 issue of U.S. News & World Report ranked the Bay Area institution the best college in America. Photos of Stanford’s campus beguiled a 9-year-old Sims. The California Avenue stop on Chicago’s Green Line “L” near his home and reruns of the Los Angeles-based paramedic drama “Emergency!” were the limits of his Golden State knowledge, but he never wavered from his goal to attend Stanford. He still recalls fshing the acceptance letter out of his student P.O. box in the Academy Center. “By the end of that day, pretty much everyone on campus knew I had gotten into Stanford,” he says with a laugh.

Sims poured himself into Stanford as he had Exeter. He walked on to the Cardinal’s national championship track team (he will forever own the school’s 55-meter dash record, an event no longer contested) and earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in biology. A sour experience with a doctor treating a stress fracture in his foot during his senior track season planted a seed in Sims’ mind that there must be a better way to perform sports medicine, but he was focused on one goal: to become a brain surgeon.

He studied neurosurgery at Stanford School of Medicine, received a fellowship from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute to conduct research in neurosurgery, and was tracking toward his goal when he began a neurosurgery sub-internship back at Stanford.

“My frst day, I got there at 8 a.m. [on Monday] and stayed in the hospital until about 8 p.m. on Tuesday,” he says. “My frst week, I [worked] 106 hours in six days.”

In addition to meeting his wife, Dr. Melissa Enriquez Sims, in medical school, Sims also was introduced to a mentor whose simple advice was to make a spreadsheet mapping his professional goals against his personal goals. “Neurosurgery hit all my professional goals and very few of my personal ones,” Sims says. “I need to work toward a more balanced life.”

NEW DIRECTION

The decision pained him — “I had told everyone in my life I was going to be a brain surgeon,” he says — but the seeds that took root years before while he was rehabilitating his foot injury steered him into sports medicine. He did a three-year emergency medicine residency at HarborUCLA Medical Center in Torrance, California, and returned to the Bay Area for a fellowship in primary care sports medicine at Stanford just as Stanford contracted to be the medical provider for the NBA’s Golden State Warriors.

That opened new doors for Sims. In addition to eventually becoming the team doctor for the Warriors, he served as a team physician for USA Track & Field and was one of the two team physicians for USA Track & Field during the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Summer Olympic Games. In May 2018, he was hired as a vice president and medical director of events for the NBA. He was promoted to senior vice president of medical afairs in December on the heels of his “bubble” triumph over the virus.

His current challenge may be even more complicated: overseeing health protocols for the new NBA season just underway — this time in 28 cities across the country as the virus spikes.

Sims calls his feeling of accomplishment “multifactorial.” He is proud of the public-health impact his work has made on virus testing, particularly the data produced from asymptomatic populations tested daily, which didn’t exist in the medical literature. And he is personally gratifed for how his high-profle role helped him bring attention to a disproportional lack of people of color in the medical feld. “We need more Black doctors. We need more brown doctors,” he says. “The bubble gave me the visibility to push that message.”

“Doing something that has an impact on sport, for the greater society and for the community, that’s how I look back on it,” Sims says. “There’s a lot of good that has been done. Completely exhausting, but so worth it.” E

Person and Path

HOW EXETER SUPPORTS STUDENTS

IN THEIR IDENTITY BUILDING

By Nicole Pellaton Illustrations by Davide Bonazzi

The question “Who am I?” is central to adolescence. The process of exploring that question with authenticity and goodness is complex and highly individualized. As the world becomes increasingly global and fast-paced, so do the challenges to identity. You need only look back to 2020’s cascade of crises and polarizations to appreciate the urgent impacts on adolescents who are in key stages of forming their identities.

“To be a teenager is to fgure out who you are, and that is something that is fundamental to the work of secondary school education,” Religion Instructor Tom Simpson says. “How do you become a full person? How do you become a person who’s not only going to have the technical skills to thrive and succeed in today’s world, but also have the integrity and the sense of self, and the confdence, and the type of relationships, and an awareness of the ways in which our world functions, to be truly who you are and let those technical skills be used for something good?”

Supporting students as they begin the lifelong journey of discovering who they are, and building self-awareness into that process so that they may continue to thrive, is a key theme of the updated Academy mission and values released last September by Principal William Rawson ’71; P’08. Exeter’s mission is to “Unite goodness and knowledge and inspire youth from every quarter to lead purposeful lives.” Five

See the full Academy mission and values at www.exeter.edu/ academymission.

timeless values outline Exeter’s commitment to provide the foundation from which Exonians can become productive citizens of the world. One value, “Youth Is the Important Period,” specifcally addresses identity work through its emphasis on instilling a “lasting capacity to nurture one’s self, develop a sense of one’s own potential and consider one’s place in the larger

whole” in order for students to develop “their values and passions and the agency needed to carry these forward.”

In these pages we take a look at some of the ways Exeter supports identity-building, including some recent innovations, through the lens of one student’s experience and in conversations with faculty. In future articles, we will continue to explore identity-building for self and in relation to being part of a diverse community.

DISCOVERY

“Something I love about Exeter is how clubs and classes feed into each other and build of of each other to help you fgure out who you are,” says Anne Brandes ’21. The club that captured this senior’s interest, starting in prep year, was The Exonian, the Academy’s studentrun newspaper. In December, she completed her year as editor-in-chief. Brandes was drawn to The Exonian as a way to make an impact on her community, but as a self-identifed introvert, she initially found the work of interviewing daunting. Over time, she acclimated and made important discoveries. “It was great that I could write and I was learning how to write. That was a really signifcant moment for me,” she says. The other discovery was people. “I can say this confdently as a senior: The point of Exeter isn’t really to get everything right or to have your homework done perfectly or be the most well-prepared when you go into class. If you’re that person, that’s excellent and I defnitely recognize why it feels comfortable to be that person, but there’s a lot to be said for taking the extra moments. … If you don’t spend time talking to people, you’re going to miss out on a signifcant part of Exeter.” A highlight of Brandes’ work at The Exonian is the “Since 1878” project, an investigation of the newspaper’s coverage of racism at the Academy. Brandes and the editors started formulating the idea in June 2020, after the police killing of George Floyd ignited outrage around the world, and as the Academy was announcing initiatives to institutionalize the practice of anti-racism. “We felt that there was a dissonance between running anti-racist articles now without acknowledging how we’ve contributed to racism and documented racism in the past,”

Brandes explains. “The Exonian was also having some serious conversations about its own racism much more recently than 1878 — more like 2020, 2019 — because of the lack of Black and Latinx voices in the newsroom.” Over the summer, a core group of writers researched and wrote the pieces that comprise the series, an amount of work that Brandes considers both stunning and indicative of her peers’ commitment to the Exeter community. To publish the series, Exonian staf spent weeks fact-checking, then Brandes and a small cadre of Exonian editors worked from 11 a.m. to dorm check-in for fve days in November. “Hopefully we can … continue to acknowl-

edge the truths that are part of the Exeter community and part of The Exonian that are harder or uncomfortable to acknowledge,” she says.

It was in a class with History Instructor Leah Merrill ’93 during fall of lower year that Brandes realized “what good writing looks like.” She attributes much of her writing progress to Merrill’s thoughtful comments, which afected Brandes deeply. The research paper from that term holds pride of place in her desk drawer. “I look at that paper and I realize, ‘I can do this. Mrs. Merrill believes in me.’”

Another key to Brandes’ development was the bookending of her work at The Exonian with two religion courses: Faith and Doubt in prep year and Epistemology in senior fall, both taught by Religion Department Chair Hannah Hofeinz. (Science Instructor John Blackwell co-teaches Epistemology.) As her focus on journalism increased, Brandes became acutely aware of the ethics of reporting. Immersion in the Epistemology course readings (a 2,000-year retrospective of knowledge, from Plato and the Western philosophical tradition, to the scientifc revolution, postmodernism and modern-day authors), and in particular a 2017 meditation by Math Instructor Jef Ibbotson on the topic of fnding truths, led to a breakthrough. “I realized that I didn’t believe in moral relativism, that I did think that pushing for objectivity was an incredibly important part of journalism … that there are such things as moral truths and that some ways of going

about the world are objectively right and objectively wrong,” Brandes explains. She is well aware of the difculty of achieving objectivity, “especially in historically white newsrooms,” and feels that the Epistemology course had an “immediate impact on my work in journalism, especially because as an editor, ethical decisions are the name of the game.”

Over her years at Exeter, Brandes pushed herself beyond her comfort zone many times and found the “moments of discomfort” to be “some of the biggest moments of growth.” “The true, amazing part of what we’re doing here is the community we’re in, the people who make it up and the stories they have,” she says. “I think that’s a collective experience that Exonians feel about Exeter: just this tremendous gratitude. You’re not feeling comfortable really until you’re about to leave, because that means that you’re

constantly trying to improve yourself while you’re at the Academy.”

For Brandes the “end goal” is “being a listener above everything else, being respectful, regardless of whether or not you agree with the position at hand, and acknowledging the unique context that everybody is in before they enter that Harkness table. … [These] are the moments where the Harkness table becomes the most hard and dangerous, but also the moments where the Harkness table has the most to give back.”

TRADITION

All of Exeter’s academic departments share the focus on helping students develop

values, identity and purpose, but Hofeinz feels that the Religion Department is exceptionally positioned because of its course catalog, which the department chair compares favorably to that of “any high school or college in terms of the robustness of the oferings and their coherence.” “We get to explore how traditions around the globe throughout time have helped people with that process, not just here now, but everywhere and always,” Hofeinz says. “The wisdom traditions, the religious traditions, the philosophical traditions, ethical traditions, all have massive archives of some of the most committed and beautiful people, writings, artifacts, ideas, dilemmas, puzzles, games: everything that we get to explore with the students and let them experience the possibilities within those diferent languages. … This allows students diferent registers into which to enter into this conversation and build on it. What does it mean to live a meaningful life? But also what type? What is meaning? What are you here for? Why are you at all?”

The faculty members of the Religion Department see identity formation as a process, not an outcome. They observe closely and use a variety of techniques to assess how students are progressing along the path of greater self-realization.

Ultimately, Hofeinz hopes to see students move toward a state of “coherence” where they are able to achieve authenticity and learn to “hold the whole — contradictions and dilemmas included within [themselves] — and be able to also recognize that other people are doing that as well. … Part of forming yourself is being able to have that coherence.”

“How do I know when they’re doing the work?” Hofeinz asks. “Can they get trac-

tion with seeing themselves? Can they get traction with saying not only, ‘This is what it is, but this is why I care.’ Or, ‘This is what I believe, but I see that there are alternatives.’ Or, ‘I used to say this, but I realized that I really said that because that’s what I always heard, and I’m not so sure about that anymore.’ Or, ‘I don’t know.’ … To me that’s one of the greatest successes at the end of a class: when a student says, ‘I don’t know, but I do know that this is a question that I’m interested in.’ … That indicates to me very concretely that they have moved from that immediate, intuitive, sure response that is not yet thought out, and there’s a refection of the middle years that they’re moving through to becoming more of an autonomous grown-up.”

“With preps and lowers, there are moments when it seems they’re trying to fgure out if the idea they hold really matters,” observes Religion Instructor Austin Washington, who came to Exeter in large part because he wanted to teach at a school where “the role of an educator is

understood to be in many respects all about identity-building or -shaping in some way.” In contrast, he sees uppers and seniors who are “more convinced of their ideas, and their ability to disagree and sustain their opinions, and allow them to be enriched, but not fundamentally changed. Those are some of the most exciting moments of identity development that I’ve witnessed,” he says, “when students understand that their ideas matter and that it doesn’t make them a bad person to have strong opinions about something, but it does matter how they share those opinions.”

Hofeinz and the other members of the department see Harkness as an ideal environment for identity formation. “That’s the strength of Harkness: It allows that dialectical movement between an individual doing their own wrangling and wrestling, and the teacher being able to interact with them one-on-one through written assignments and individual conferences and conversations, but then really emphasizing that it’s in the students’ mutual interactions that they’re pushing each other to think slightly more and to come at it from diferent directions,” Hofeinz says. “It’s in that community work that the individual becomes possible.”

INTENTION

Self-authoring is the name of a new program developed by the College Counseling Ofce that asks lowers to consider who they are through a series of conversations and written refections, all based on identity-related questions, such as: Who infuences you and how? or, Where are you happiest? These forays into explicit identity work have the double beneft of initiating the college process with a focus on and understanding of self, as opposed to societal trends or external pressures, and introducing the college counselors to younger students in a friendly and supportive way.

“Self-authorship is a way of empowering adolescents,” explains Dean of College Counseling Betsy Dolan. “Being self-actualized and being content with not just who you are, but the fact that you can see yourself growing and that you’re going to continue to grow — you can make decisions

that are informed.”

Dolan was inspired to start the program after reading research by Marcia Baxter Magolda, a professor emerita at Miami University of Ohio and a leader in self-authorship theory. Recognizing a clear link between self-authorship and encouraging intentionality in Exeter students, Dolan introduced the concept to her team. Counselors Courtney Skerritt and Jef Wong developed a curriculum specifc to Exeter lowers.

The program launched as a pilot with

new lowers in the winter term of the 2019-20 academic year. Partnering with the Health and Human Development Department, college counselors, in pairs, visited several sessions of HHD240: Thriving in Community, a course that focuses on developing decision-making skills based on purpose and thoughtfulness.

The two-session program culminated in a Harkness discussion about fundamental questions: What does Exeter mean to you? Who are you at Exeter?

“Every class was diferent,” Wong says. “It usually started with the concrete steps of what is Exeter. But then it became so much more, and that’s where you’d see people jump in and say, ‘I had a very diferent experience choosing to come here,’ or, ‘I’ve had a very diferent experience since I’ve gotten here.’ Some people talked about it from the 30,000-foot level of what it means to them or their families. For others, it was much more on the ground: ‘This is a change from where I grew up.’”

Skerritt observed in the self-authoring Harkness conversations a clear willingness among students to “unpack” identity preconceptions, and an openness to new points of view, including those brought by students from around the world and from a tremendous diversity of personal experiences. She sees particular value in exploding some of the negative impacts of social media on identity-building: “With social media, it’s really easy to listen to the voice that is your own echo in terms of political beliefs, background and interests. But you don’t know who you’re going to be with at the Harkness table. … I see Harkness as the anti-social media.” Although the college counselors planned to reconnect with the lowers during spring term and again in the fall, the coronavirus pandemic put a temporary halt to those eforts. The college counselors are looking forward to rolling out the full program once in-person classes resume. “The best thing that could happen is students have this experience over the winter and spring terms,” Dolan adds. “We meet with them in the fall to remind them of it. And it informs their college process to such a degree that it doesn’t matter where they go. They know they can feel good about their person going forward, whatever the adventure is.”

THRIVING

Exeter’s Counseling and Psychological Services team provides another framework for identity formation based primarily on one-to-one meetings between a counselor and a student. The keys to creating a supportive environment for identity work, says Szu-Hui Lee, director of CAPS, are

providing a “safe place, trusted adults, trusted relationships so that students can explore diferent aspects of themselves and know they’re still cared for, and know they are not judged.” For some Exonians, Lee says, fnding their voice can involve healing from experienced trauma. “What we know about trauma work is healing starts when people feel safe,” she says.

CAPS ofers free counseling to Exeter students while they are on campus. During the pandemic, as some states have loosened licensure regulations and allowed out-ofstate counselors to provide care, CAPS has been able to ofer remote counseling to an increasing number of students who live outside of New Hampshire. The fve coun-

selors can provide a level of service that is unheard of in public schools and even at many universities, where individualized appointments can be strictly limited, Lee says. “We can see students every week if there is a need, from the time they are preps to the time that they’re seniors. … What does that mean? Some of the things that people might unpack in their adulthood or in college, our students have the opportunity to start a little earlier because they have these resources.”

Lee’s advice to students is: Explore, explore, explore. “This is the time to go down every aisle in the grocery store and check everything out,” she says. “See what’s of interest. Discover things that are diferent and unfamiliar. And fnd joy in what you know and love.”

The hoped-for result of this exploration is to anchor habits during four very formative years. “Studies have shown that if you form habits at an early age, that includes between 14 and 18, you’re more likely to have those habits stay with you as an adult,” Lee says. “And it doesn’t end when you graduate from Exeter. … Positive self-identifcation means that you allow yourself the permission to continue to evolve. … At 24, when you decide to change your mind about something you thought you were pretty darn sure about at 14, that’s OK.”

For many students, Exeter can be a bit of a jolt. “A lot of our students’ identity is grounded in their academics,” Lee says. “They’ve been on this journey to get ahead, get to Exeter, with the hopes that a great college would be next on their trajectory. They’re following markers that they themselves, or society, or their families have set for them.” When those markers are missed

— students don’t get the straight-A’s they are used to, or they get injured and can’t perform at their sport — they can falter and wonder about their own identity, sense of purpose and direction. “Counseling comes in around that time to say, how do we modify or create new markers? Let’s explore all aspects of who you are beyond the measures you are used to.”

Lee explains: “I often tell students, think of a stool. There are three legs to a stool to hold it steady. When one is broken of, you can probably still lean on the other two. Healthy self-identifcation is making sure you know your identity comes from a collection of things that make you who you are. So, you have to make sure to have a lot of legs of diferent things, so that when something in your life isn’t going well, you’re still getting feedback from other things that matter to you, and holding steady. … That’s how you thrive: You have other things to lean on.” E

KETV 7

Ryan Pettit ’21 pens letters to veterans weekly to help ease their loneliness during the pandemic lockdown.

It was summer 2020, and Ryan Pettit ’21 was on the phone at his parents’ home in rural Papillion, Nebraska, answering questions about corn. His interrogator on the other end was an elderly friend, confned by COVID-19 restrictions to his room at a nearby veterans home in Norfolk. The friend wanted to know, how was the year’s crop looking? (Healthy.) How tall, on average, were the plants? (Six feet.) This being Nebraska, the nation’s number three state in corn production, the topic was of perennial interest during the pair’s weekly phone calls. “You take it for granted, seeing the corn grow outside your window,” Pettit says. “But you can’t really see it from his home.”

Curiosity satisfed, the veteran (whom Pettit declines to name, citing privacy concerns) turned to another favorite topic. “What he really likes,” Pettit says, “[are] puzzles. He talks to me every time about puzzles. He’s even built a 3D one!”

Despite chatting for months, the two have never met in person. Their telephonic friendship began in the spring, when Pettit — marooned at home for the foreseeable future and itching both to ease his own isolation and to mitigate the loneliness of others — decided to reach out to elderly veterans. The son of a veteran himself, he wanted to express his gratitude to those who’d served. And he’d seen the COVID-19 lockdown’s toll on his own grandparents, confned to their rooms in a Florida nursing home. “The isolation was terrible,” he says. “They almost just wanted to give up and leave the home and risk the pandemic. To be stuck in your room like that … it’s just miserable.”

Pettit contacted Nebraska’s three veterans homes to ask whether residents would enjoy weekly phone calls. Deb Becker, volunteer coordinator at the Norfolk Veterans’ Home, responded quickly, and was surprised to learn that Pettit was acting independently. “When we frst spoke with him, we thought it was a school project,” she says. “But he said no, he just wanted to do it because the veterans

were alone and couldn’t be with their families.”

Pettit helped Becker establish a Skype connection, then created a system: At a prearranged time, he would dial the facility, where a resident would be waiting. After chatting, the resident would trade places with another interested party. Amid the swirl of conversationalists, his friend emerged as a steady, weekly presence. “This gentleman has some PTSD,” Becker says, “and he needs that one-on-one contact.”

This impulse to foster personal connections comes

naturally to Pettit, who grew up in a family rooted in community and steeped in a culture of non sibi. His father, a civilian strategist in the U.S. Strategic Command, served for 28 years as a Navy pilot and captain, and was deployed to Iraq when Ryan was in kindergarten. It was community, Ryan says, that buoyed the family during and after that time — the military community, whose members understood the toll of parental absence, and the Pettits’ rural Nebraska neighbors, who became what he calls an “extended family,” delivering cookies and helping to fx the family’s leaky plumbing. He’d never forgotten their kindness, and made it his mission to treat others similarly.

He brought this spirit of reciprocity and empathy to Exeter, where he co-founded a nonpartisan student political journal devoted to “respectful discourse,” and where he co-led ESSO youth basketball games and served as a Wentworth dorm proctor. Pettit takes proctoring seriously and has continued his duties remotely, for which his adviser, Sean Campbell, is grateful. “I think the role of proctor has a huge component of selfessness,” says Campbell, an instructor in computer science. “A lot of personal time is devoted to making sure students are welcomed and feeling connected to others, [which is] especially important for remote students.” During the pandemic, Campbell asked Pettit to organize online activities for the other dorm students and was delighted with the care Pettit took. “He did a great job putting this together,” Campbell says, “and those in attendance had a blast.”

While tending remotely to young and old, Pettit has also been nurturing some smaller, nonhuman charges: A lifelong gardener, he spent spring break last March sowing a 300-plant nursery in his family’s sunroom, complete with a homegrown vermiculture composting system.

Early last summer, he learned that a center serving low-income children and families wanted to build a community garden in downtown Omaha. “I said, ‘I can do this for free!’” he laughs. He brought 40 or 50 plants over from his own garden and planted them at the community center. With typical forethought, he built raised boxes with plexiglass windows so “kids could see the carrots growing in the box, and the potato tubers growing underneath the soil.

“I really enjoyed nature growing up,” he explains. “I thought it’d be nice for kids from places in the city where they maybe weren’t exposed to that to be able to garden.” The Omaha–Council Blufs, Iowa, area has a high concentration of “food deserts,” according to the Omaha Community Foundation, meaning many families struggle to fnd afordable produce. As Pettit’s home garden grew to bursting — it seems 40 tomato plants can yield thousands of tomatoes — he began ferrying over his own peppers, cucumbers, tomatoes and herbs, delighted to share with needy families the vegetables of his labors.

While he was fostering growth and greenery, however, life in veterans homes was contracting and darkening daily. COVID-19 restrictions had halted outings and interactions with the outside world for residents. Indoors, strict room-capacity limits meant no more games or bingo nights. At most, two residents were allowed at a table. Social life was nonexistent. Already at particular risk for loneliness and social isolation — both associated with higher rates of depression, anxiety, suicide, stroke and heart disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — the elderly were reeling.

The ongoing misery made the moments of joy even more poignant. One of Pettit’s happiest days came when a Norfolk nurse told him that staf had never been able to persuade his veteran friend to attend physical therapy. Now, after each call, the resident headed to PT without complaint. “You’re making a large diference in his life,” she told Pettit.

“I didn’t really imagine this to be that impactful,” he admits. “I thought it was just kind of a nice thing to do, to brighten the vets’ days a little, but as soon as I heard that, I thought, ‘I’ve got to try to do something more.’”

He wanted to expand his phone initiative, but while his relationship with Norfolk was strong, his connection to other veterans homes was, quite literally, faltering. At some, poor bandwidth made for glitchy and unreliable communication; others had limited technology, meaning there might be only one device among residents. Some residents didn’t want to interact with newfangled Skype or Zoom, or with phones at all. Pettit tried to

enlist local friends as callers, but wrangling a posse of teenage volunteers into some semblance of consistency during a pandemic proved difcult, and too often, callers would renege, leaving veterans waiting in vain. “It was extremely frustrating,” Pettit says.

Last summer, he decided to eschew electronics entirely and embrace an older technology: pen and paper. He began cold-calling veterans homes across the country asking whether residents would enjoy receiving citizens’ letters. Ultimately, 29 veterans homes from 23 states signed on. To amplify his eforts, Pettit created a website, Hellos for Heroes (hellosforheroes.org), explaining the initiative and urging visitors to write. The mission was simple: “to brighten the days of the many retired veterans stuck in isolation at residency homes.”

Other than encouraging gratitude, he avoided posting editorial guidelines. The point was simply for writers to chat in their own voice, leaving recipients a bit cheerier than before. The site features a sample letter from “Shannon” — a transplanted Georgian, new owner of a rambunctious puppy, peanut-brittle connoisseur — who turns out to be Pettit’s mom. Pettit refuses to post the family surname, because, he says, “It feels cheesy to me when people stamp their name all over volunteer work.”

“Ryan has never been one to boast about his work or his achievements,” Campbell, his adviser, says. “That just seems to be his personality.”

Once the website launched, Pettit spread the word via Facebook, friends, relatives and media outlets. The publicity blitz worked. “My website trafc has gone way up,” he says. “About 1,000 people or so have interacted with the site, so I imagine if half those people are actually sending letters, that’s 500. I’m happy with that!” Local media has come calling. Daughters of the American Revolution awarded him its Outstanding National Community Service Award for 2020, and 110 DAR chapter members pledged to write letters in December. “Probably the time vets need letters the most,” Pettit says, who spends up to two hours weekly writing letters.

Becker is delighted with the initiative. “We’ve gotten a lot of letters and cards, a lot of calls from people who heard about it on the news,” she says. Most missives arrive from Nebraska, but some hail from as far as Washington, D.C. Her staf pass around the letters and make sure to read them aloud for residents incapable of reading on their own. Other veterans homes post letters to a community board, or save them for residents having a particularly difcult day.

Pettit’s one disappointment: “I don’t really receive letters back,” he says. Veterans homes are cognizant of HIPAA rules and wary of scams, so letters are monitored and residents generally discouraged from responding. Pettit’s letters haven’t reached any PEA alumni that he knows of, but the more writers, the better the chance. Even though he doesn’t receive responses, he knows that Hellos for Heroes missives are appreciated. “A lot of [Norfolk’s veterans] think Ryan is older than he is because he’s so polite and respectful,” Becker says. “He asks questions: ‘What’s your favorite ball team? What do you like to eat?’ It’s helped them pass the time. And the families really appreciate it, too.” Lately, residents have been assiduously following Pettit’s college-application process, hoping for happy results. “The guys are so anxious to see how far Ryan goes in life,” she says. “He has really stuck with [us]. He’s just the sweetest young man.”

So what’s next for this empathetic entrepreneur? In college, he hopes to dual-major in biology and economics. At Exeter, his biology classes so inspired him, he launched his own research project studying human metabolic processes; and well before COVID-19, he’d found the world of pharmaceutical development and biotechnological innovation intriguing.

For now, he continues his senior year remotely, writes letters, and, of course, tends to his plants. He calls his grandparents, who are surviving isolation, and speaks to his veteran friend weekly. He accepts all media opportunities to publicize Hellos for Heroes, because ideally, he’d like to see every veterans home in the country deluged with letters from grateful citizens.

Pettit would love to launch a letter-writing program for all retirement facilities, but with an estimated 15,600 nursing homes in the U.S., it’s a steep goal. That said, he’s shown himself to be a gifted and creative problem-solver. “He is doing great things despite the fact that they may be less visible,” Campbell says. “He’s a great kid and a phenomenal scholar.” Don’t put it past him. E

Impact

Every time Connie Liu Trimble ’80 advances the fght against cervical cancer; every day Maria Cabildo ’85 lifts the disadvantaged with her work on low-income housing; every essay Roxane Gay ’92 pens for those in need of a champion, we are reminded that Exeter is not a fnal destination. It is a path to a purposeful life.

Likewise, as we hail 50 years of coeducation at the Academy, we recognize not only our alumnae’s time on campus yesterday but the women they’ve become and the contributions they are making today.

Trimble and Cabildo have earned recognition as John and Elizabeth Phillips Award winners. Gay is a best-selling author and an opinion writer at The New York Times, who delivered the keynote address last month during Exeter’s annual MLK Day. They are exemplary in that they are representative of so many of their fellow alumnae: a blend of goodness and knowledge, embodying the spirit of non sibi. Like a Harkness discussion that resonates long after class has ended or a season-ending victory over Andover, it is the way it should be.

In the following pages, we meet fve alumnae who — like Trimble, Cabildo and Gay — are among the thousands of Exonians doing good works, pushing boundaries and living the values they expressed as students at Phillips Exeter Academy.

IN THIS ISSUE

44 Her History 47 Exeter's 12th Principal 48 Her Voice ... in Action 54 Her Voice ... in Reflection

Her History

KEY HISTORIC EVENTS IN THE COEDUCATION TIMELINE FROM 1980 – 2000

Compiled by Patrick Garrity

Women in the Faculty Get a Boost

William L. Dunfey, father of alumna Julie Dunfey ’76, donates funds to further improve opportunities for women teaching at Exeter, resulting in the establishment of the Committee to Enhance the Status of Women.

APR 11, 1980

Gloria Steinem Headlines Exeter Conference

Exeter hosts a national conference of more than 200 women in independent school education. Speakers include Gloria Steinem, Carol Gilligan, Estelle Ramey, Natasha Josefowitz, Pauli Murray and Eleanor Holmes Norton.

JUN 22–25, 1983

Women Bolster Faculty Ranks

Eighteen of the 24 new full- and part-time instructors for the academic year 1985-86 are women.

SEP 1985

JUN 1981 Four-Year Girls Graduate

Included in the Academy’s bicentennial class are dozens of girls who arrived as preps, the first four-year boarding girls to graduate.

NOV 18, 1983

Trustees Commit to Hiring More Women

The Trustees approve plans for afirmative action to increase the number of women on the Academy faculty. Only one-quarter of the Academy faculty are women, while 40% of the student body are girls.

JUL 1, 1985

Herney Becomes Dean of Students

Susan Jorgensen Herney, a longtime member of the dean’s ofice, begins a six-year run as dean of students, the first woman to fill the role.

Men tend to pick those with whom they feel most comfortable, and men feel comfortable with other men. ... Te selection process is very male-oriented.”

—Assistant Principal Lynda Beck, on the lack of women in Exeter’s faculty, November 1983

Exeter is strong enough that it need not hesitate at appointing a woman to the position. It is a recognition that the Academy is moving with the times.”

Girls Comprise 43% of Student Body Stewart Makes StuCo History

—Chairman of the Trustee Search Committee Chauncey C. Loomis ’48, on the selection of Kendra Stearns O’Donnell as the school's 12th principal, Feb. 21, 1987 The school year begins with a student enrollment of 985, including 424 girls.

SEP 22, 1988

Carmen Stewart ’92, a rising senior from South Carolina, is the first girl to be elected president of the Student Council.

MAY 1991

FEB 21, 1987

O’Donnell Chosen as 12th Principal

Trustees announce the appointment of Kendra Stearns O’Donnell as Exeter’s 12th principal, the first woman to hold this position.

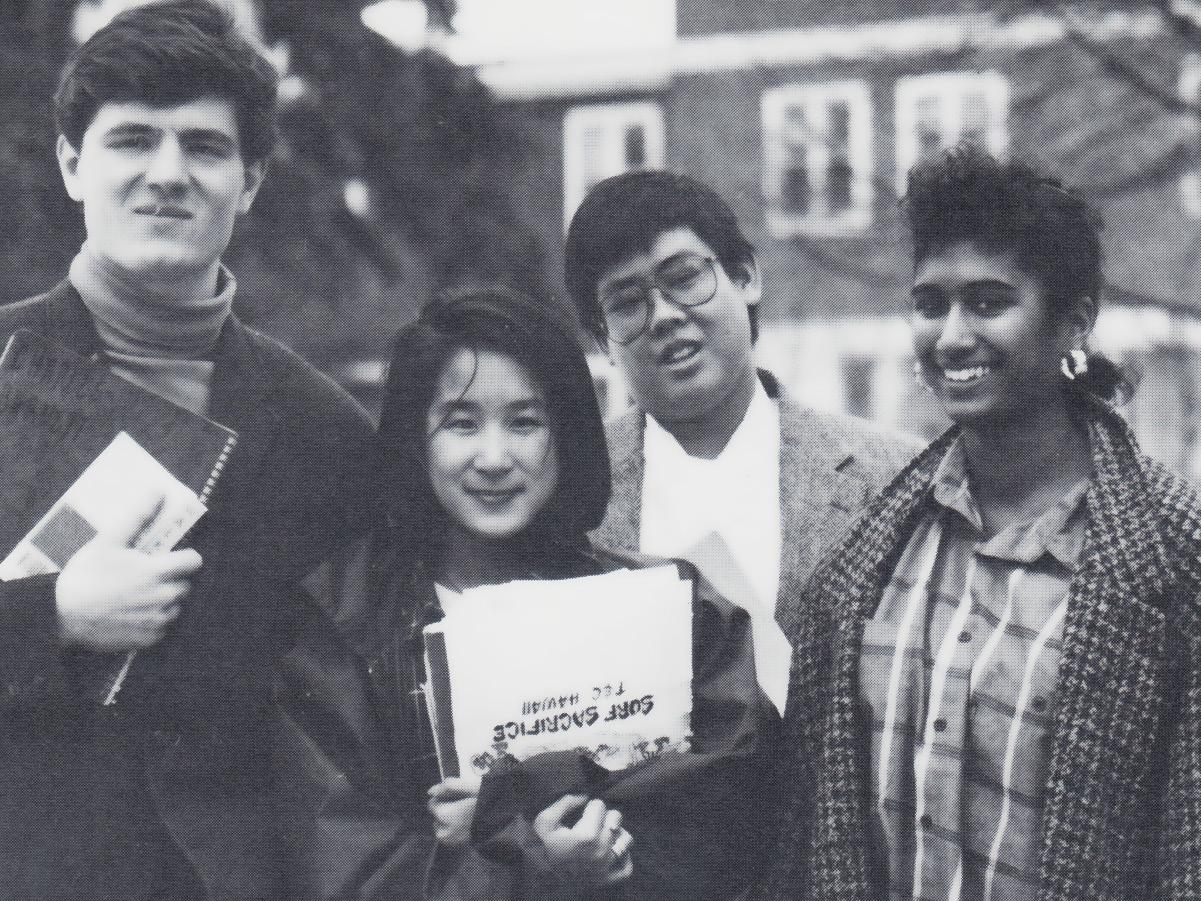

SEPT 21, 1987

’A Place in History’

Kendra Stearns O’Donnell delivers Opening Assembly remarks, welcoming students and faculty ”not just to this lovely school ... but to a place in history.”

JUL 1993

Kendrick Honored as First Emerita

Dolores Kendrick, the Vira I. Heinz Instructor in English, becomes Exeter’s first retiring woman instructor to be extended emerita status.

Dolores Kendrick in 1980

Coeducation Anniversary Honored

The Academy kicks of a yearlong celebration of coeducation’s 25 years with an assembly that pays tribute to some of the first women who joined the faculty.

SEP 25, 1995

Academy Building Gets Face-lift

Academy Building lintel receives a new Latin inscription honoring the first quarter-century of coeducation: “HIC QUAERITE PUERI PUELLAEQUE VIRTUTEM ET SCIENTIAM.” (“Here, boys and girls, seek goodness and knowledge.”)

APR 16, 1996

Student Enrollment Reaches 50-50 Split

The 2000-01 school year is the first in which enrollment is evenly distributed between boys and girls, reports then-Director of Admissions Thomas Hassan.

SEP 2000

It was very disappointing to see that no one acknowledged during Coeducation Weekend that women brought more to the school than dresses and feld hockey — namely, intelligence and a drive that was equal to that of the boys.”

—Marissa King ’97 and Reyhan Harmanci ’97, in an Exonian op-ed, Oct. 21, 1995, after the school’s reflection on coeducation.

We are really still evolving. … Each year we learn a litle bit more about living and working together in a coed environment.”

—Susan Herney, September 1995

JUL 1, 2000

Eggers Takes Over as Dean of Faculty

Barbara Eggers, an instructor in history, becomes dean of faculty. She is the first woman to hold this position.

To see the full coeducation timeline, visit exeter.edu/coeducation.

Exeter’s 12th Principal

By Patrick Garrity

Other than the groundbreaking decision to enroll girls, few milestones in the Academy’s coeducational journey measure up to the hiring of Kendra Stearns O’Donnell as the frst woman to serve as Exeter’s principal.

The Trustees announced to the campus community on Feb. 21, 1987, that O’Donnell would be assuming the role upon Principal Stephen Kurtz’s retirement that June. The announcement concluded a search process that O’Donnell nearly won after one interview. “Why don’t we stop the search right now? Why are we looking anymore?” a member of the nine-person search committee is reported to have asked.

History is not so hasty, however, and this decision was unquestionably historic. After all, no formerly all-boys preparatory school in the United States had chosen a woman to run things. O’Donnell had won over the search committee; but the committee had to convince the Trustees. Another fnalist, a man with a more traditional résumé, was a safer choice than O’Donnell, who at the time was not in academia but rather working at a private philanthropy.

A story about O’Donnell’s frst months on the job merited 3,000 words in the Sunday New York Times and recounted how the selection ultimately came to pass:

“In the end, the search committee prevailed. At a meeting in the fusty downstairs billiard parlor of the Century Association (which does not yet admit women as members), the committee members persuaded the board of trustees to see things their way. ‘The trustees decided that if this is the way the school feels, we don’t dare not take her,’ one participant said.”

O’Donnell told The Exonian on the day of her appointment, “Exeter is in a period where it is examining the old ways, and seeing how it can make things work better. I especially want to examine just what it means to be a coeducational school today. I am going to listen a lot,” she said, “to listen and to learn. This is a school that knows where it wants to go.”

Last fall, in a conversation with Principal Bill Rawson ’71; P’08, O’Donnell spoke about her selection. “I think I felt like every new student at Exeter: I was full of imagining all the great things ahead and also some nervousness about everything being so new.

“I was excited to be a part of Exeter’s history. I was less wrapped up in being the frst woman and more conscious, I think, of being the 12th principal at this ancient and revered institution.” E

Watch O’Donnell and Rawson’s conversation at exeter.edu/principalstalk

Her Voice ...

in Action

ALUMNAE WHO ARE MAKING THEIR VOICES HEARD, EMPOWERING OTHERS AND ADVOCATING FOR CHANGE

Shirley Jennifer Lim ‘86

By Debbie Kane

Shirley Jennifer Lim ’86 discovered the focus of her life’s work in a stack of flms in UCLA’s Paramount Pictures archives.

A doctoral candidate at the time, Lim was researching the history of Asian American women in flm. She was especially fascinated by Anna May Wong, an elegant Asian American actress whose career spanned silent flms, talking pictures, stage, radio and television. While reviewing Wong’s flms in the Paramount archives, Lim was struck by her performance in King of Chinatown, a 1939 black-and-white flm. “She was speaking in a British accent, portraying a surgeon,” Lim says. Asian female characters at the time were often portrayed as prostitutes or evil temptresses. “Wong’s portrayal blew the customary narrative out of the water,” Lim says. “My interest was piqued.”

Lim, now a history professor at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, has long been interested in the history of Asian Americans, especially women. The daughter of Indonesian immigrants, she grew up in Bakersfeld, California. (Her family had previously lived in Libya and Scotland.) When her family moved to China for her father’s job, she headed east to attend Exeter, the frst in her family to go to boarding school.

Her frst book, A Feeling of Belonging: Asian American Women’s Public Culture, 1930-1960, is the book she says she wished she’d read while attending Exeter and, later, Cornell University. “Coming from an immigrant family, from the Central Valley of California, and having parents who’d escaped mass murders in Indonesia in the 1960s, it was very hard to be there (at Exeter). I didn’t feel at home or understood,” Lim says. She singles out English instructor Peter Greer ’58, Exeter’s frst BatesRussell Distinguished Professor, as a supportive teacher who inspired her to write.

A Feeling of Belonging examines how Asian Pacifc American women established identities in Southern California by creating their own sorority, beauty pageants and more. “Most Americans think of racism as being white versus Black, but on the West Coast, it was Asian Pacifc Americans that were segregated from society, especially from the 1930s to the 1960s,” Lim says. (That included being barred in California from marrying a white person.) “Asian American women’s history is very understudied. History and historical sources accrue around famous, elite people, especially men. It’s harder to come up with records about women.”

Lim’s most recent book, Anna May Wong: Performing the Modern, is getting acclaim at the same time that Wong is being recognized as the frst prominent Asian American flm star and for creating a 20th-century persona not defned by ethnicity. Lim examines the actress in the larger context of race, contrasting her work with other prominent actresses of color who played Asian

roles in flms from the 1920s through the 1940s, including Black actress Josephine Baker and Mexican actress Dolores Del Rio. “It’s a more interesting and complete way to think about Wong — that race is developed in conjunction with other races,” Lim says. “The Modern” in her book title refers to the way Wong fought typecasting of Asian characters and made them modern; she humanized Asian Americans during a time of intense racism, when laws such as the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred Chinese immigration to the United States, discriminated against Chinese immigration and citizenship.

The national conversation around racial diversity and equity is enabling Lim to share Wong with larger audiences through television and radio. She’s also writing another book about the actress. “It’s great from a scholarly perspective but also a political perspective to foster greater gender and racial equality,” she says. “It’s why I get up in the morning and why I teach. I hope my work is having an impact.”

Often with tech, you think there can't be a big impact — everything's in the cloud. ... But there can be both environmental and social impacts ... ."

Madelyn Postman ’90

By Sarah Pruitt '95

For Madelyn Postman ’90, a commitment to protecting the planet goes back to her years at Exeter, when her friend Scott Heald ’88 made an ofand comment — “Out of sight, out of mind” — as Postman threw something in a nearby trash can. “I realized that our waste doesn’t just disappear when you throw it away,” Postman says. “That has stuck with me all these years.”

More than three decades later — after experience working as an in-house creative at Gucci Group and consulting for brands such as Burberry, Sunglass Hut and Nokia — Postman has merged her core interest in sustainability with her expertise in branding and marketing as co-founder and director of Grain Sustainability, a management consultancy with a mission to help businesses “become champions for the planet.”

The new company builds on Grain Creative, a branding and design agency Postman ran alongside her husband, Christoph Geppert. The agency merged with Leidar, an international communications consultancy, in 2018, and Postman began working as the managing director there. But when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and Postman found herself in lockdown with Geppert and their two children in their home near London, she realized she needed to make a change.

“I was able to step back a bit and think, do I really want to be doing this?” Postman recalls. “There’s always this desire to not just be a vessel for clients’ work, but to really try to change things more fundamentally.”

In late 2020, Postman and Geppert left Leidar to found Grain Sustainability. In their new roles, she says, “we can really work with the fundamental day-to-day operations of a company to ensure that it’s more sustainable.” Clients include companies in the education, technology and transportation felds, both in the United Kingdom and abroad. “Often with tech, you think there can’t be a big impact — everything’s in the cloud,” Postman says. “But there can be both environmental and social impacts, depending on what the company is doing.”

That lightbulb moment by the trash can wasn’t Postman’s frst exposure to the concept of sustainability.

Growing up in San Francisco, she became aware early on that water was a scarce, valuable natural resource. During her four years at Exeter, she remembers joining Amnesty International and participating in protests against the newly constructed nuclear plant in Seabrook, New Hampshire.

Postman considered pursuing environmental studies at Brown University before deciding instead on a double major in visual arts and art history. She spent her junior year abroad in Bologna and ended up staying for the next eight years, working for various design frms before landing the job at Gucci. She returned to the United States only to complete her degree at Brown in late 1994.

Her experience in Italy introduced Postman to what seemed like a more sustainable way of life — one that felt less tied to the ubiquitous consumption that she had come to fnd oppressive. “I remember just feeling a bit depressed when I walked into a big store full of stuf,” she says. “In Italy, you go to the market and buy fresh fruit and vegetables in paper bags. There aren’t as many big chain stores as in the U.S. and the U.K. I look back on those years a bit wistfully, thinking that’s the way we should all be shopping now.”

Postman moved to London with Gucci Group in 2000, but left two years later to co-found the design frm Vivian Cipolla. Before joining Grain Creative, she established her own agency, Madomat, which focused on providing art direction, graphic design and 3D design with a focus on eco-friendly materials.

In addition to her work with Grain Sustainability, Postman is on the U.K. steering committee for 1% for the Planet, a movement that encourages businesses and individuals to contribute at least 1% of their annual turnover or income to environmental causes. She’s also working on a narrative nonfction book, Sixteen Stories, based on her family’s roots in China, Poland, Lithuania and California.

Postman credits her Harkness experience with preparing her as a frequent commentator on branding and business for BBC World and a public speaker at universities, business schools and other venues — and in the corporate world in general. “As a woman, being articulate and having the confdence to speak up really helps,” she says.

Harkness also helped her understand early on the diferent ways people can show leadership. “Saying what you think is part of it, but you don’t always have to be talking just for the sake of it either,” Postman points out. “It’s about knowing when to say something: I believe in ‘quiet leadership.’ ”

Camilla Norman Field ’93; P’24

By Jennifer Wagner

Camilla Norman Field ’93; P’24 remembers vividly the frst time she visited San Quentin Prison. “There was that jarring moment when I heard the clank of the door, when I was in the sally port between the outside and the inside,” she says. “You notice your nervous system responding to that and you also recognize that you’re coming in with a certain bias. I’ve seen Shawshank Redemption, but I thought, is that really refective of what I am walking into?”

Turns out, it wasn’t. As a professional certifed coach with the Enneagram Prison Project, Field regularly meets with incarcerated individuals in correctional facilities across Northern California. “I don’t see people who are nothing like me because of the lives and choices they made,” she says. “I see human beings who are in the condition and position they are in as a result of tremendous childhood trauma.”

In courses that span up to fve months, Field teaches an eight-module curriculum designed to help inmates

It is not OK to just sit back and coast and enjoy the ride. It's a much more enriching and wonderful life knowing that I'm both receiving support and giving support ... ."

validate their self-worth and foster self-awareness. “Starting from week one, it’s always some combination of self-acceptance, self-regulation, self-compassion, understanding that there’s actually nothing wrong with them,” Field says. “They’ve done some things that have certainly caused harm to themselves, to individuals, to communities and they’re very aware of that. It’s not about erasing that, but there are things that happened to them that led them to those choices and there’s redemption. There’s a way forward. No one is too far gone.”

Field frst became passionate about reforming the criminal justice system after one of her dearest friends from Exeter was arrested on a drug distribution charge. “Through him, I learned about mandatory minimums and asset forfeiture and the inherent racism in the drug war,” she says. Field helped her friend acquire an attorney and, after his conviction, a commutation from then-President George W. Bush. He served eight and a half years of a 14-year sentence.

“Even though I couldn’t fx my friend’s issue directly, I could work on the policies around the country,” she says. For fve years before joining Enneagram Prison Project, Field advocated with the Drug Policy Alliance to address failed drug war policies.

While reckoning with America’s history of mass incarceration was new for Field, a natural inclination to help others wasn’t. At Exeter, she was an active member of ESSO and recalls tutoring a local woman in math in order to help her earn her GED. “That sense of agency, that sense that even at that age, I had an important role to play to make my local community better really landed with me,” she says.

Field continued on this path at Princeton, studying history and taking on a leading role within the university’s Big Brother Big Sister program. After graduation, she worked in fnance and held a series of temp jobs before joining buildOn, a nonproft committed to ending poverty through service and education. “It is not OK to just sit back and coast and enjoy the ride,” she says. “It’s a much more enriching and wonderful life knowing that I’m both receiving support and giving support and just feeling that connection.”

It is that sense of connection that keeps Field motivated. “I remember one student at San Quentin,” she says. “We asked everyone to write their names and he wrote his surname. So, I said, ‘Write your frst name.’ Over the course of the class, I kept saying his name. At the end of class, he said to me, ‘You said my name. You said it a lot.’ I said, ‘I did. How did that feel?’ He said, ‘I don’t think I’ve ever been seen before.’ That was just heartbreaking to hear. But it makes me remember that just being present with someone is such a gift no matter what the circumstance.”

Meredith Hitchcock ’06

By Sandra Guzmán

Meredith Hitchcock ’06 grew up near Capitol Hill, and every morning on her drive to grade school her parents were extremely enthusiastic about wanting to teach her the history that had been made in her backyard. She remembers when her father pointed to Constitution Hall and told her how in 1939 opera superstar Marian Anderson was barred from performing there because the building, owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution, banned Black performers.

“I would hear them and think, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah, more history,’” Hitchcock says with a laugh. “I thought government was boring.” Of course, she adds, “I appreciate with distance and time how foundational growing up in D.C. and the center of government was, and how the city and my parents’ seeds helped shape me.”

For the past six years, Hitchcock has used her skills to develop technological solutions in the service of social justice. “I work with people who do the coding and help guide them in terms of the technology by making sure that anything being built is oriented toward solving real problems for real people, not just to increase revenue by x percent.”

Her interest in technology was frst piqued during her lower year at the Academy when she learned simple programming, as well as the importance of being a role model for others. “It’s ironic that the experience of being one of two women and the only Black student in Java and HTML classes at Exeter prepared me for Silicon Valley,” she says. “I learned that I must occupy spaces even if no one else looks like me and not feel intimidated. It also left me with a sense that I have to always pull up an extra chair and mentor women and young people of color.”

Hitchcock studied comparative literature at Yale University, then went to work at Google, where she spent fve years as a product specialist in digital publishing while pursuing a master’s degree from the University of California, Berkeley, in information management and systems.

Hitchcock’s tech activism began after she read Michelle Alexander’s groundbreaking book, The New Jim Crow. “I am, by nature, a risk-averse person,” she says, “but a friend pushed me to think about what kind of decisions I would make in my career if I weren’t afraid.”

The question led the 32-year-old to quit her lucrative job at Google and become a justice design fellow for Code for America, a government technology nonproft where she began developing RideAlong with another fellow. The data-driven criminal justice app helps frst responders and police ofcers de-escalate situations with people who are having a mental health crisis and connect them with social services. So far, 11 American cities, including Seattle, are using the interface to great success. “It’s gratifying to help police departments re-envision what technology can do and help support this shift from the warrior mentality to the guardian mentality,” explains the entrepreneur.

After the app was sold to OpenLattice in 2018, Hitchcock worked at Promise, a cash bail-reform startup. Now she is at Airbnb, where she is a design and user-experience researcher focusing on inclusion, accessibility and equity. During the earlier part of the last year, she collaborated with the company’s philanthropic arm to launch a global initiative to provide free or subsidized housing for COVID-19 health care providers, relief workers and frst responders. Hitchcock, who lives in San Francisco, spent hours on virtual calls interviewing hosts. “To be a witness to all the highs and lows people are going through was very powerful,” she says.

During her free time, Hitchcock volunteers with U.S. Digital Response, a nonproft that works to improve local and state governments’ responses to the COVID19 pandemic. “I really believe in government now, but in local government in particular, because it has the most immediate impact on the quality of life for people,” she says. E

To read and hear more stories from Exeter alumnae, visit exeter.edu/coeducation.

Editor’s Note: The following meditation was shared with the campus community on October 26, 2020.

Hello from afar. I picture us in Phillips Church, music just ending. I am standing in front of you, but actually the setup is diferent — as so many things are these days. I am in my living room, recording and thinking of you there at Exeter, and hoping it is a beautiful fall day and you are doing well. I will imagine I am there with you.

I’m very cognizant of this incredibly strange and endlessly challenging moment in which we fnd ourselves. There is so much for us to meditate on right now — really, too much. So, before I proceed, I want to acknowledge that many of you are in pain today, and all of us know other people in great pain. Pain from the health and economic impacts of the pandemic, which are being borne disproportionately at every turn by communities of color; from the fact of and reckoning with widespread racial injustice in our country; from the stress on our democracy and the polarization of our country and our communities; and from so many losses of people we cherish. Before I share more, I hope you’ll join me in acknowledging our individual and shared pain, here in community ... .

My name is Jen Holleran; I am class of 1986, from the great dorm Wheelwright, and I am a trustee in my 10th year of service. It is my honor to get to carry on the tradition of a retiring trustee giving a meditation. I may not be your frst-choice candidate to do so in this moment in history — I am a white middle-aged woman who grew up with enough privilege that my father is an alum of Exeter from the 1950s, and all three of my sisters also attended. Nonetheless, here I am to share with you the story of my love of schools, how my experience at Exeter helped shape that love, and of the journey of focusing on working toward quality education for every child.

Let’s start with some context. Exeter is an extraordinary place, as you know, with its centuries-long commitment to “youth from every quarter” and the social mobility that implies, and with alums that hold that commitment as their highest priority. While not perfect, we have a clear purpose and we work to continuously improve. And, by virtue of being here, all of us have some degree of privilege. For each person, the privilege and the challenges are meted out by life in diferent measure, with little consideration of fairness. Both make us who we are.

This fall, after six months of virtual school and a very long summer break, dropping my twin sons of at school has been a diferent experience than in the past. Often, I fnd myself close to tears as I drive in and see kids playing or talking, and I send my boys of with an “I love you, have a great day” as they close the door, with their eyes focused on their community, the other sixth graders around them.

My heart swells with joy that they are able to go to school and be with their peers, to be with their amazingly dedicated teachers and school leaders. That they are able to leave me behind without a word if they choose, to set of on their own and take on their own challenges. Who knows how long school will stay open, but every day on campus with their classmates is precious — and we treat it as such.

One son’s comment at the end of that frst day — “Mom, that was a good day” — let me know they appreciate what is going on here and how lucky they are to be back. It is a privilege only a small percentage of the country is experiencing.

I think of you, coming back to Exeter, which for so many of you has become home, the place your friends are; the place where your academic, athletic, arts and other pursuits await you; where your teachers, coaches, advisers, D hall staf, school leaders and others work so hard to enable these opportunities for you. Many of the adults around you have worked tirelessly all summer and wrestled with incredibly difcult decisions, all so that you could come back here to be together safely. The many changes in this time have made clear to the whole world the critical role of school for students’ academic, social and emotional growth, how incredibly essential teachers are, and what an art it is to be a good teacher. You are surrounded by such teachers.

Some of you have been here for seven weeks now; for others, you may be newly arrived and are just starting to make it your place. For all, I hope, it is an amazing year.

One thing I ask you to consider during this meditation and in the days to come is: “What makes a good day for you?”

This year stands out for so much loss of opportunity in schools that haven’t opened. For students who don’t get to be with their peers. For the millions of students who don’t even get to go school. For the many who are doing hybrid or online learning, and particularly those who don’t even have the connectivity to make remote learning a meaningful reality. Research shows the impact is most dramatic for the students who were most behind to start with, and each week of the school closures widens the divide. The pandemic has put on full display what has been true all along: Our education system is not equitable, those with the least are often given the least, and those with the most fnd an abundance of options.

And now a bit of my story. My appreciation for Exeter started before I ever arrived, with truly terrible ffth and sixth grades. Middle school may be tough on everyone; my version of that particular agony was moving to a new state and showing up at my new school at close to my full adult height of almost 5-foot-10, well on the way to becoming one of the strongest and bigger-boned women you are likely to meet. Since stores presumed 10-year-old girls were small and there was no internet shopping, I had to shop at middle-aged ladies stores or in the boys department. I was new, stood out, and felt unwelcome.

Fifth grade was terrible: being made fun of daily to the point of what we know today as real bullying, not making a single friend, and teachers not showing any sign of noticing. Despite the seventh and eighth grades being much better, my experience had left an indelible mark.

Thankfully, Exeter was diferent; I knew it right away. When I arrived here that gorgeous fall day in 1983, my family pulled up in our car loaded with my stuf to the sidewalk outside of Wheelwright. I looked up at the brick building and breathed a sigh of excitement and relief. This was my dorm, my community. This would be the place where I would live with other students and they would get to know me; no early judgments would carry much weight because they would get to know me, the substance of me, and they would like me.

It was an intense realization. I was not disappointed. It was a transformational fall, and a transformational three years. The proctors and older girls opened their arms to the new lowers and preps, and we dove into dorm life. We got to know each other fast and intensely, the doors of our rooms becoming permeable boundaries where we crossed in and out of each other’s spaces with ease, complaining about chem labs or getting homework help, borrowing sweaters, and delving into deep conversations until late in the night. Mr. Hertig would chase us out of each other’s rooms, working hard to try to demonstrate he was annoyed that we were up late talking, but you could see that the power of the bonding going on was not lost on him. I had found my second home.

In classes, I was intimidated by Harkness at frst, amazed by the returning lowers who had such clear opinions and the ability to share their ideas. Then by late fall, I realized they were just experienced at Harkness (Harknessing, I think you say), and I found my voice around the table and started having fun in class. Homework and classes every Saturday seemed endless but purposeful, and there were all of my dormmates to commiserate with, so we were happily resigned to both. Mr. Polychronis opened my eyes with his genetics course and Mr. Tremallo brought short stories to life, even in a new course called “Writing on the Computer.”

I loved the challenge of sports and got to know upper-class women as I played on the feld hockey, squash and lacrosse teams. What at frst seemed a crazy expectation — that we were going to run Drinkwater as just a warm-up — quickly became the norm, and I learned to push myself. Mrs. Anderson was one of the best coaches I ever had, even after I played two Division I sports in college. She taught us to prepare well, rise to the challenge of the moment, and be honorable in victory or defeat, and she showed us how much better we could be when we truly played together. As we celebrate 50 years of coeducation this year, I think back and can only imagine all that she, Mrs. Nekton and others did to make us not even notice that we were only in the frst decade of girls’ sports teams.

When I refect on my experience at Exeter, it was really formative in three main ways:

The frst was the great gift of making lifelong friends. Those friendships have become my sustaining relationships, the bedrock in my life along with my family. From those friendships, I have one clichéd piece of advice, simple but hard to do: Keep in touch with your close friends even when it is inconvenient, enjoy the things that bond you, work through your diferences, push each other and fnd the time to get together in person! That seems easy now, but a decade or two out, living in diferent cities or even diferent countries, with pressures of jobs and children, getting together in person can be a challenge.

Every year for the past 35 years, my close friends and I have met somewhere fun, with restaurants to go to, mountains to hike, or arts to explore. But despite whatever great attractions there are, we often end up having the best times of the weekend sitting on the foor in pajamas or sweats, laughing ridiculously, looking a bit like teenagers in a dorm.

This was my dorm, my community. This would be the place where I would live with other students and they would get to know me ... the substance of me, and they would like me."

The second way Exeter was transformational for me was the plethora of small communities within the school, whether the dorm, teams or classes, that enabled me to be seen and heard and belong. This reality was particularly pronounced for me, set against those awful early middle school years. One of the exceptional things at Exeter is that there are so many opportunities to join small communities that allow each person to fnd their place to belong. I hope you each fnd your place.

The sense of myself I developed at Exeter around the Harkness table and in leadership positions in the dorm and on the feld built a formidable foundation. My sister and several professionally successful women friends from the class of ’91 refected recently on all they had taken for granted about what being at the Harkness table did to set them up to enter the working world with the presumption that they had a full voice at any table, and the confdence and skills to take on the many battles in their careers as women.

Finally, my experience at Exeter catalyzed what has become a lifelong drive to create school communities and growth and learning experiences like those I found here at Exeter — but doing so at scale, often in more challenging circumstances and on more limited public funding, so that all children can get a quality education. A fter college, I started teaching at Deerfeld Academy. It was 1990 — long before you were born. I was a 22-year-old, brought in to help integrate girls in what was only the 12th month of coeducation at a school that was deeply rooted in tradition, so I got more experience trying to shift a culture than I had bargained for. I loved teaching, coaching and even being on duty fve nights a week in the dorm. I found myself drawn to the students who had to work hardest to ft in, for whom I wanted to create a bridge. Often these were students who were low income, or people of color, or gay or lesbian students.

Right: Jen Holleran in 1985. Below: Holleran, top row and third from left, with the Exeter field hockey team and Coach Anderson in 1985.

In my mid- and late 20s, like many, I explored around a bit. During graduate school, curious about the broader world of public education, I tried an internship with a principal in an urban high school. I saw crowded classrooms, often disengaged students, a range of teachers from good to horrible, and a system where I couldn’t fgure out how to even enter in an impactful way. I ended up limiting my job search to independent schools, and went on to lead a high school division of a private day school — a place I recognized and comfortably slid right into. While my responsibilities had broadened considerably, my world had not.

Later, I had the opportunity to work on a short consulting project with the superintendent in the Oakland (California) Unifed School District, who was aggressively opening small schools in an efort to replace poorly performing elementary schools and high schools that had such bad results that researchers refer to them as “dropout factories.” When I went to visit the new small schools and met the school leaders from the community, I was deeply moved by the engaged, joyous belonging happening for students, almost all of whom were students of color, many living below the poverty line. I saw enough resonance with what I had experienced at Exeter, I could fnally see that I might be able to apply what I knew of quality small-school communities to a school with students with broader needs in a more resource-constrained setting.

It was 2002, and as that consulting project was wrapping up, a woman named Katrina Scott George asked to meet. She was just joining the district to lead the ofce of school reform. She had a clear idea, I realized in retrospect, that I might be useful. She handed me a book instead of engaging in traditional interview questions. It was titled The Answer to How Is Yes. She challenged me with the question: How do we make equitable schools? How do we battle the injustices all around us. She let me know that in her mind, the answer is you do something, you start somewhere, you bring what you have, and you work to see where you can fnd an opening to make the next step of progress, because no opening is likely to show itself until you are in the fght. She wanted to know, “Was I In? How hard would I fght for kids?” And in that moment, I realized I wanted to do that work, this work that had broad reaching purpose, to dive into the world of educational equity and of systemically broken districts. It wasn’t at all comfortable, but I knew that if we could be successful it could be trajectory-altering for thousands of students.

Katrina was a Jamaican-born woman who had seen big change in her country and believed signifcant progress was possible. She came to the U.S. to study engineering, got a good job and stayed. When she had her own kids and started to see how badly underserved the Black and brown students in her East Bay neighborhood were, she adapted her engineering skills into focused work to transform underserved schools. She was the mastermind behind our work. We became focused on how to build more equitable schools, give principals the training and autonomy they needed, and work with communities to meet families’ needs. We recruited and helped develop dozens of school leaders for the movement, each of whom was committed to creating equitable, caring, rigorous education communities.

We made lots of progress — built some great schools, helped improve others, trained many leaders who today lead schools or whole networks of schools. At the same time, we had our gaps and made plenty of mistakes. It is work whose results are measured not in weeks or months, but in years or sometimes decades. And so we persevered, did all we could, and are still, almost two decades later, seeing results unfold.

My own life was disconcertingly divided; after long days in the Oakland schools I would drive across the Bay Bridge, which separated the two cities, my two worlds, to San Francisco. By that point, I felt I no longer fully ft in either world. In San Francisco, my mind was often questioning the things around me — the excess of fancy restaurants, second homes, and private schools with unrivaled views of the Golden Gate Bridge. In Oakland, I stuck out visually and otherwise. Often the only white person in a room, I faced people who looked at me askance, wondering why I was in this work, people who at times pointed out how little I had experienced of injustice and how limited my language was around racism. I learned so much as I worked directly with families in Oakland and learned about the power of parent community organizing groups, about getting policy passed at school board