24 minute read

The Journey to a More Sustainable Inner and Outer World

The Journey to a More Sustainable Inner and Outer World with Jerry Yudelson

By Sasha Frate Jerry Yudelson is a LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) Fellow—the highest achievement for a LEED professional in the green building industry—a Federal GSA (General Services Administration) National Peer Professional, a registered professional engineer with more than twenty-five years’ experience, and the author of fourteen books on green buildings, water conservation, green homes, green marketing, and sustainable development.

Advertisement

Yudelson’s work is focused on the long-term environmental impact of urban developments on climate change, specifically greenhouse gas emissions resulting from the operations of homes and buildings. With a B.S. in engineering from Caltech, an A.M. in water resources engineering from Harvard, and a M.B.A. from the University of Oregon, Jerry is an irrefutable expert on green living. A pioneer in organizing Earth Day activities in 1970 on the Caltech campus, Yudelson also taught some of the first university courses in the U.S. in the new field of environmental studies at the University of California Santa Cruz.

Jerry has been a driving force in the green building movement since 1997 and co-founded the first U.S. Green Building Council chapter in 1998. He also served a six-year term as chair of the steering committee for Greenbuild, helping to develop it into the largest green building conference and trade show in the U.S.

In The World’s Greenest Buildings: Promise vs. Performance in Sustainable Design, Yudelson was the first author to address building performance. In his latest book, The Godfather of Green: An Eco-Spiritual Memoir, Jerry shares his unique journey through three major environmental movements while simultaneously pursuing an ancient spiritual path.

Jerry connected with Face the Current and graciously shared his insights into the benefits of meditation, the ways in which we can relate to and live in harmony with our planet, the need for the reinvention of the green building movement, and his recommended green-living action-steps that we can incorporate into our daily lives.

Sasha Frate: You’ve done significant work for the “outer world” of humanity with your sustainability efforts for the planet, and green building and living. In your latest book The Godfather of Green: An EcoSpiritual Memoir, you delve deep into the “inner world”. Why did you decide to go “there” next?

Jerry Yudelson: The inner world is always part of us. Nothing happens without us first thinking about it. And for many, as it was for me, it’s our thinking patterns and habits that keep us stuck. What happened for me is that when I turned thirty, I was blessed to encounter a spiritual master and find a path that I have followed ever since. In the book, I describe how I struggled for a decade to reconcile these two seemingly different worlds, until discovering from within the ways in which I could integrate my personal mission of protecting the earth and my desire for inner realizations and put them into service for each other.

SF: In the beginning of your memoir you point out that, “Children intuitively know and love the earth. From the time their mother puts them on the ground to crawl, the earth is a constant companion.” What have you identified as the biggest contributors to our separation from this childhood intuitive connection when we enter adulthood?

JY: For many of us, it’s when we as teenagers begin to focus more on academic studies and respond to peer group pressure that we start to lose our intuitive guidance and begin to let the “culture” lead us. We start living in our heads, looking only to satisfy the senses, and in doing so, forsake our sense of wonder. Today, social media, Instagram influencers, and incessant screen time amplify this effect. As a younger teen, I used to spend many evenings stargazing, but I gave up that passion in high school for sports, studies, and social life. Like most people, it took a big challenge— an abrupt change in circumstances— to force me to reconsider my life’s direction. For me, the catalyst was dropping out of a high-level PhD program and going to live by myself in the woods of Northern California in a Thoreau-like experience of povertyof-means while opening myself to the riches of the imagination and a growing knowledge of the workings and wonders of the natural world.

For me, the catalyst was dropping out of a high-level PhD program and going to live by myself in the woods of Northern California in a Thoreau-like experience of poverty-of-means while opening myself to the riches of the imagination and a growing knowledge of the workings and wonders of the natural world. “ “

SF: In your book The Godfather of Green, you tell of part of a Sufi qawwali recorded by Gurumayi that recognized how, “The world instructs me: become this, become that; become this, become that; become this, become that… (But) by becoming no one, I have found my Self in ALL.” You elaborate on this, sharing a summary: “To find your (great) Self, you first must lose your (small) self.” What a beautiful recognition! What are a few ways you’ve found and can recommend helping this process of losing one’s “small” self and find his or her “great” Self?

JY: Every great being has given the same message—turn within. Meditation is the easiest means for self-discovery and the royal road to Self-knowledge. But we need a guide—someone who’s traveled the entire road—to keep at it. You must want this experience, recognize its value, and find someone to give you instruction. Every true seeker finds a way to get a practice going. The teacher is the catalyst, but you alone must make the effort to establish a regular practice of turning within, resting in the peacefulness of the Self, spending time there for a while each day, and then letting that spirit of love and kindness guide you as you move through the outer world.

SF: You describe balance as “a life art” in your book. How would you describe the impact and repercussions on the individual level when we are out of harmony in living with our planet, and a few simple changes to bring back one’s life into better balance and harmony?

JY: I have found that living disharmoniously is incredibly stressful, because when you’re out of balance, you’re always oscillating between positive and negative emotions and you only occasionally find your center between pendulum swings

I have found that living disharmoniously is incredibly stressful, because when you’re out of balance, you’re always oscillating between positive and negative emotions and you only occasionally find your center between pendulum swings from one extreme to the other. I find the best way to get back into balance is to focus on seemingly insignificant things that you can control, however unimportant they may seem to others. “ “

from one extreme to the other. I find the best way to get back into balance is to focus on seemingly insignificant things that you can control, however unimportant they may seem to others.

These days on my daily walk, I take time to pick up a few pieces of trash along the road and put them in a nearby container. In a store, I always smile at the cashier and say something uplifting. Once someone asked my teacher a deeply spiritual question and he offered only this simple advice: “Do something kind for someone today.” The person wanted a more “profound” teaching, but that simple direction was what they needed at the time. If you bring your “A game” to each encounter with others, they’ll notice; human beings are incredibly intuitive and can easily recognize the intention behind the smile or kind words.

Sometimes, I’ll pause while walking my dog in the early morning and just look at the sky. An ancient technique for expanding consciousness is just allowing your awareness to lose itself, to merge in the vastness of the sky. If I hear birds singing, I’ll pause to find where they are in the trees or on the roofs and listen for a moment, waiting until I can see the bird. There are so many simple things you can do, but the essence of spiritual practice is to pause and reconnect; pause and reset; pause until you feel the inner bliss arising, and then take that awareness into your day’s activities. If you feel disconnected during the day, pause and let the blissful feeling arise, then begin again.

SF: You stated that, “As a society, we [have] to become as heliotropic as sunflowers.” Solar technology has come a long way in moving us in this direction. Can you explain a bit about how it has evolved, where you currently see us, and your prediction on whether we can indeed become “as heliotropic as sunflowers” in our society?

JY: Every camper knows that if you want a hot shower, all you must do is hang a water-filled black plastic bag in the sun for a few hours. Everyone notices how a brick wall gets warm when the sun shines on it and retains that warmth well into the evening. It’s common knowledge that food plants thrive in the sun and die in the shade. More than 100 years ago, homeowners used simple solar technology for making hot water in Los Angeles, but by the 1920s, cheap fossil fuels began to displace wood and sun for this purpose.

Einstein discovered and described the photoelectric effect in 1905, but it took researchers more than 50 years to create the first working photovoltaic cells. By the 1960s, solar cells powered our satellites and ocean buoys. In the mid 1970s, I led efforts for the state of California to develop a solar power industry based on solar water heating. But again, in the 1980s, cheap oil and gas, along with the ending of solar tax credits, stopped that effort. Finally, about twenty years ago, we began to use cheap solar panels to create electric powerplants. Since then, solar use has quickly grown into a global movement and now represents the best long-term solution to decarbonizing our economy and power sources.

A hundred years from now, living on a much hotter and far less hospitable planet, people will look back on the fossil-fuel era and wonder why human societies waited so long to deploy solar and wind power in far greater amounts. If we are to avoid the worst consequences of global climate change, we must move quickly to base our entire economy on renewable energy, the power of sun, wind, growing plants, and falling water.

SF: Tools such as daily meditation and mantra repetition are attributed to bringing one back to the state of peace, love, and steadiness, a state in which you describe as having been a back and forth process to get to. But, you go on to share that, “Bliss is our very nature,” and that, “Most of us love to talk about our suffering, our victimhood, our troubles and grievances; but we fail to seek out, experience, and live in our innermost nature, which is nothing but a body of bliss.” What do you advise as the greatest steps away from the suffering and victimhood and towards a body of bliss?

JY: Stop listening to other people and listen instead to your own heart. Many people keep a “gratitude journal” and each day recall something for which they are grateful. Others practice positive thinking, looking for the lemonade in every lemon of life experience. Ultimately, we learn the same truth that’s been known since ancient times and fully explained in Indian scriptures such as the Yoga Vasistha, which is “the world is as you see it.”

We have incredible power to shape our own perceptions, memories, and attitudes. All we must do is turn our back on what one famous sales trainer called “stinkin’ thinkin’.” But it takes lots of inner work to give up that sense of victimhood that we love to recall and relive—much as a pig likes to roll in mud—and realize the truth of our own nature; we are and always have been beings of bliss, no matter what has happened to “us” in mind, body, and emotions.

SF: You speak of dropping self-importance to “live more honestly” and with a “sincere spirit”. Why do you believe this is typically such a difficult challenge for most people to achieve, and how would you describe the result of living our lives more honestly and with more sincerity and empathy?

JY: Dropping self-importance is the work of a lifetime for most people, including me! As children, we come to believe we live only because we put ourselves first, and of course my parents also encouraged that sense of “specialness” even as they showed by example how one also could offer service to others in the community. There’s this constant struggle between egotism and altruism that we all deal with. Over time, inner Great beings have gone through the same struggle to give up their egoattachment and realize their essential oneness with everyone and with God, so it’s no wonder that we too must make a similar effort! Ultimately, if we are fortunate in our practices and diligent in giving ourselves to this great love, we naturally begin to live honestly, sincerely, and empathetically. In the end, it becomes who we are, simply because we have identified not with ourselves as a lone individual but with the higher-Self that lives in everyone and everything.

SF: What did you discover as some of the differences between the USA and Europe in terms of green building?

JY: From a technical standpoint, there isn’t much difference. It’s more cultural and in some cases, legal. For example, in Germany you can’t have anyone sitting more than seven meters (about twenty-two feet) from a window. So, for example, every office building must be less than forty-four feet wide. A German would consider placing anyone farther from a window immoral and unethical because it’s human nature to want to see what’s going on outside. We also know it’s healthier.

There’s this constant struggle between egotism and altruism that we all deal with. Over time, inner work begins to bridge that gap and to reveal to us our common humanity. “ “

The lesson for me was simple: it was as if you designed software without ever valuing the user experience or creating a functional user interface, like in the early days of “apps” for the web. Technical experts create eco-labels, not those who own or operate buildings. Until that approach changes and building owners feel more engaged with the process of creating the eco-labels, we will never move en masse to zero carbon buildings which are essential to confront global warming. “ “

In the U.S., by contrast, real estate developers want to cram as many people as possible inside a building footprint, so the emphasis has been on much wider building floors, where some people might sit fifty or 100 feet from a window, or even be entirely closed off from a view outdoors by tall partitions.

Also, in Germany, for example, the architect is legally in charge of construction and completely responsible for the final product. In the U.S., the architect is just another player on the design team, and the contractor has responsibility for delivering the building as a finished product. As a result, sustainable design ideas often get tossed as the contractor (and subcontractor) tries to maximize profit by throwing out “extras” that may make a building healthier or cheaper to operate, but which add initial cost.

SF: One of your encouraging core rationales for green building has been that. “Green buildings are about people. We shouldn’t see buildings only as consuming energy and generating carbon emissions that we must reduce. Buildings are there for people to live, work, play, and study in. They should aim to make people healthy and productive. That’s where we can create real and lasting benefits.” But, despite the surge in green building from the 2000s to approximately 2012, it came to a virtual standstill. Can you summarize what happened that essentially halted everything and how you foresee us reinventing the green building movement?

JY: Well, I wrote a whole book four years ago called Reinventing Green Building, so if anyone is really interested, they can read the full argument in that book. What essentially happened around 2012 was that growth in the use of “ecolabels” for buildings essentially plateaued.

If you were developing a “Class A” office building in a large metro area, you were going to build it green and get it certified because tenants were

willing to pay a little extra rent to be in it. If you were a large university or major corporation, you built green and paid for the certification because your students and employees were asking for it. But for almost everyone else, the extra cost, time, and hassle to get a certification just weren’t worth it. That didn’t mean that architects and building owners stopped using or valuing sustainable design measures, but they no longer saw the formal “eco-label” as essential.

The lesson for me was simple: it was as if you designed software without ever valuing the user experience or creating a functional user interface, like in the early days of “apps” for the web. Technical experts create ecolabels, not those who own or operate buildings. Until that approach changes and building owners feel more engaged with the process of creating the eco-labels, we will never move en masse to zero carbon buildings which are essential to confront global warming.

One principle in the Indian approach called Vastu Shastra is to make sure that everyone gets morning sun since they need that energy boost in the morning. In the Chinese Feng Shui approach, one considers the entire energetic feel of the building and how earth energies affect emotional well-being. “ “

SF: In one of your previous books, Green Building A to Z: Understanding the Language of Green Building, you cover an array of topics on sustainable building from Renewable Energy and Passive Solar Design to Native American and Native Canadian ways of living, and Zen and Vastu Shastra. These are some incredible concepts that not only apply to sustainability, but also to our overall wellbeing. Can you share a few examples from Native ways of living, Zen, and Vastu Shastra that you believe to be ideal for us to incorporate more into our building and lifestyle?

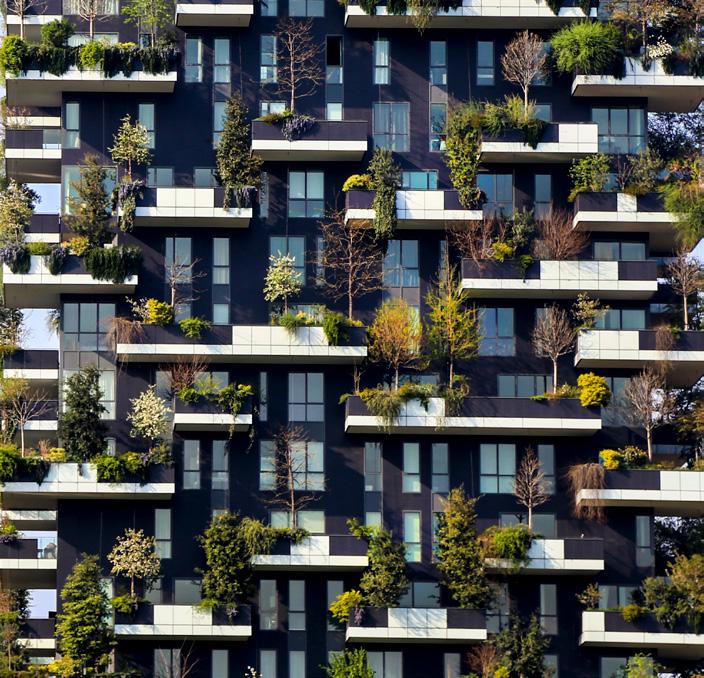

JY: The essence of traditional building design is to use local materials; take sun, wind, and water into account during design and keep things simple. Until the advent of the modern sustainable design movement, building design had lost touch with these principles, with perhaps Frank Lloyd Wright’s “organic architecture” as a lone exception. Buildings adapt to many different uses over a lifetime of 100 or 200 years. Stewart Brand wrote a wonderful book about this, called How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built. One of the key phrases I learned from early thinking about sustainability is that the best approach to designing buildings is to make them “long life, loose fit, and low energy.” That phrase summarizes the essence of green design and is where building design needs to go. For example, there’s a huge movement now to build massive timber buildings. They’re going to be twenty, thirty, or forty-story buildings, but with a much lower “carbon footprint” than the conventional steel, glass, and concrete high-rise building.

About forty years ago, I built a passive solar adobe house in the San Francisco Bay Area with my wife, which was primarily earth, wood, and glass and it was oriented to get maximum solar heating in winter, yet still be cool in summer. It had a deeply spiritual feeling to it and an emotional resonance that’s hard to describe. Today, people are beginning to adopt a similar standard called Passive House that works with many building materials.

Most people aren’t going to want to live that way, but traditional designs offer insights into orienting buildings toward the sun and turning their backs on prevailing winds. For example, one principle in the Indian approach called Vastu Shastra is to make sure that everyone gets morning sun since they need that energy boost in the morning. In the Chinese Feng Shui approach, one considers the entire energetic feel of the building and how earth energies affect emotional well-being. Feng Shui works—I once changed the entire feeling of my home’s entrance in Portland just by hanging a metal sculpture outside the front door after doing a formal Feng Shui assessment.

SF: It’s fascinating how many of the sustainable techniques that you share are ancient practices from various cultures around

the world. In a world that often prides itself on our modern advancements, it seems that we need to reflect on which of these advancements are destructive while also returning to an integration of many ancient techniques and practices that can better serve us and our planet. What are some of your favorite references (or examples) of ancient techniques and practices in this sense?

JY: Most of the issue is, once again, cultural and not technical. We know a lot about “the timeless way of building”, but traditional cultures didn’t mind sweating in summer and putting on a sweater in winter. In our modern Western culture, we want constant comfort year-round. That’s hard to do without using a lot of energy to keep temperature and humidity always within a comfortable range.

The issue is that people vary tremendously in their needs: my wife is always cold and I’m always a little on the warm side. In Tucson, it was easy—we had a house with two zones and two A/C and heating systems. There was a “her” side and a “his” side in terms of thermal comfort. In summer, her zone was always ten degrees Fahrenheit warmer than mine. To help things out in that desert climate, we put in highly efficient windows and planted trees to shade the east and west windows with movable shading on the south side where we had no room for trees. In the desert, the rule is to keep direct sunlight out of the house, because sunlight equals heat. In cooler climates, you’d want to do just the opposite! There are about eight distinct climate zones in the U.S., maybe a few more in Canada, and you need a different approach for each one. We can study techniques from ancient cultures, but we need to adapt them to modern living and cultural preferences.

SF: There is a connotation with green and sustainable living, even health food store shopping, as being expensive and out of range for many people’s budgets. Can you shed some light on this and share some of the ways in which green building, conversions, and lifestyle implementations can be affordable and maybe even save money?

JY: On energy use, it’s always “pay me now or pay me later.” To the extent possible, we should all be tightening our homes with better windows and insulation and supplying most of our electricity (for home and auto) with rooftop solar or purchased green energy. We all know that we’ll eventually save lots of money, but we realize we’ll have to invest money to get there. For example, solar power has a high “return on investment” but if you must spend $20,000 or more up front to get that return, many people don’t have the resources to do that.

So, the key issue is having excess funds to make the investment and that’s where issues of income inequality come in. Right now we’re

testing how millions of people can get along without a regular paycheck for even two or three months. We will find out how few people have any savings at all, let alone enough to last for several months of essential spending. The real issue with green or sustainable living is to reduce demand first before you start investing in exotic ways to increase supply, for example, of solar electricity.

My wife and I have always grown some of our own food. We’re basically vegetarians, almost vegans, and we don’t drink alcohol, so we can economize on food. Lifestyle choices are more important than most people realize, and they are the best way to cut food costs, allowing us to eat organic foods and stay healthy without busting our food budget.

SF: The “larger issue” of climate change has moved to the forefront for you since the green building movement slowed down. What have been some of your primary advocacies with climate change?

JY: I began writing about climate change issues about ten years ago when I called out the lack of interest by green building NGOs in documenting the energy performance of buildings they certified. In 2013, with a German journalist friend, I published The World’s Greenest Buildings, presenting real-world performance data on dozens of green buildings from eighteen countries. In that book, I presented metrics for evaluating “best in class” performance in Asia-Pacific, North America, and Europe. In 2016, my book Reinventing Green Building argued that the lack of independent performance data made any claims about the climate benefits of green buildings suspect and open to challenge.

In writing my memoir, The Godfather of Green: An Eco-Spiritual Memoir, I added an Epilogue in the form of a “Letter to a Young Climate Striker” as I wanted to share a few things I had learned. It’s never technical issues that matter most, as many solutions are well researched and presented in books such as Paul Hawken’s

Drawdown. It’s about attitude and preparing for a long struggle to get beyond our fossil-fuel-based economy.

In the Letter, I point out that the biggest political successes of the last century were based on love and nonviolence: Gandhi in India, Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. in the United States, and Nelson Mandela in South Africa. Climate change is an existential crisis to be sure, and the current system has massive inequities, but the path toward lasting change must be rooted in getting people to come over to your side through the power of your ideas and the passion of your love.

SF: With regards to climate change and green living, if everyone did these seven things, it would have significant positive impact:

JY: Talk to someone now, while we are all open to hearing what might happen with the coronavirus pandemic, about what will happen as climate change begins to raise the

Earth’s average temperature first 1.5C and then 2.0C beyond preindustrial averages. We’re at about 1.0C now and are beginning to see the effects in increased droughts and floods, forest fires and freak storms, heat waves, and disease outbreaks. Most surveys show that up to ninety percent of all people in the U.S. are willing to discuss and learn more about the climate crisis. Effective political action won’t happen until a significant majority favors it.

1. Support student climate strikes and other climate crisis actions. When it’s safe again to have mass demonstrations, attend if you can to show young activists that their parents and grandparents “have their back.”

2. Check your own energy use habits and see where you can cut down ten percent or more.

3. Support local farmers’ markets and grow some of your own food so that it doesn’t have to be trucked in from somewhere far away. 4. Eat lower on the food chain, vegan if you can manage it.

5. Recycling makes less sense now that China has stopped taking most of our trash, but it’s still something everyone can do. Urban recycling is stuck at around forty percent, but it still has a prominent role to play. If you own a home (and you can afford it), put solar panels on your home and/or buy an electric vehicle.

6. Cut back unnecessary travel. Because we’re all now learning how to work remotely and that we can more easily “visit” so many exotic locations remotely, doesn’t it make more sense to explore the small piece of the planet that’s right at your feet, to learn the names of native plants and birds, identify the watersheds in your bioregion, and become a true “inhabitant” of where you live?

7. Take a walk in an old-growth or national forest, on a local nature trail, or simply along the beach. Identify and count the birds flying overhead. Clear your mind, reconnect with

nature, and stay engaged with the real purpose of green living, which is to leave the Earth just as we found it, maybe even better, for the benefit of succeeding generations.

ymore info: www.reinventinggreenbuilding.com

Green Building A to Z: Understanding the Language of Green Building Reinventing Green Building The World’s Greenest Buildings How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built