5 minute read

PORTSMOUTH HISTORIC DOCKYARD

PORTSMOUTH HISTORIC DOCKYARD

When HMS Prince of Wales joins her sister ship at Portsmouth, she will be in some very illustrious company. Ian Goold looks at some of the historic ships already at Portsmouth.

HMS Prince of Wales enters Her Majesty’s Naval Base Portsmouth following sea trials, she will berth for the first time at the home port from which she will deploy over the next five decades. That affords the prospect of a half-century’s service set in the context of a very much longer maritime story preserved in Portsmouth Historic Dockyard. The base has been an integral part of Portsmouth city for more than 820 years, more than 500 of which are represented by four grand old ladies waiting to greet HMS Prince of Wales: Mary Rose, HMS Victory, HMS Warrior, and HMS M.33. A

Mary Rose

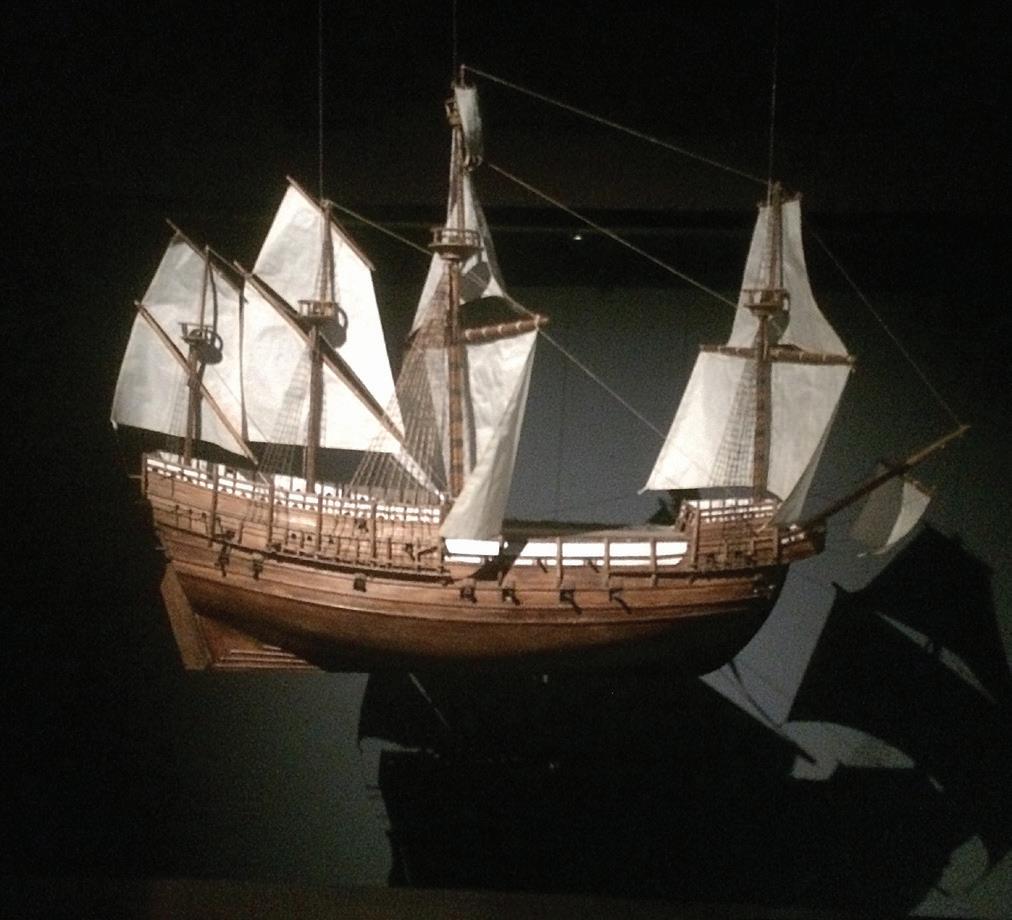

Built in 1510, and the only 16th-century warship on display, King Henry VIII’s flagship Mary Rose is preserved in a museum that captures the moment she sank in the Solent in 1545. Her story covers 30 years of British battles against the French, her re-discovery in 1971, her subsequent resurrection from the seabed in 1982, and her conservation by the Mary Rose Trust. Mary Rose is displayed in a £27-million museum in No. 3 Dock, where floor-to-ceiling glazing on the lower and main decks enables visitors to view the Tudor vessel. Almost 20,000 artefacts, including many weapons (from longbows to two-tonne guns) and personal effects (leather footwear, musical instruments, nit combs, and wooden bowls), provide a unique insight into the ship and the lives of her crew.

Photo by Megan Michell

Henry VIII’s flagship, Mary Rose, saw action against the French before sinking in the Battle of the Solent in 1545.

Photo by Megan Michell

In the 1512-14 First French War, Mary Rose had taken part in the Battle of Saint-Mathieu. Between into dry dock at Portsmouth. Annually, 400,000 people visit her to see the spot – marked by a brass plaque on the quarterdeck – where Nelson fell. The ship is undergoing a 13-year, £35-million conservation programme to repair and maintain her structure and improve the system of supports within her dry dock, overseen by conservation, engineering, heritage, rigging, shipbuilding, and timber-preservation experts. This work has included a £2-million conservation project in 2013-14 for routine maintenance, painting, surveys, and a thorough overhaul of the ship’s boats.

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson’s flagship during the Battle of Trafalgar, Victory, is preserved at Portsmouth Historic Dockyard and visited by 400,000 people every year.

Barry Swaninbury- Fleet Photograph Crown Copyright

1522 and 1536, when she was held in reserve, the ship was re-caulked and refitted. Reports of the circumstances that preceded her sinking at the Battle of the Solent are conflicting, but it is clear that many hundreds of sailors died when Mary Rose sank. Early attempts to raise her were abandoned and she remained undisturbed until divers discovered the vessel in 1836.

HMS Victory

Some 250 years younger than Mary Rose, HMS Victory is the Royal Navy’s most famous warship, best known for her part in the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. She currently serves as the flagship of the First Sea Lord and as a living museum to the Georgian Navy at the National Museum of the Royal Navy.

From 1778 to 1812, HMS Victory participated in five naval battles: the First and Second Battles of Ushant, the Battle of Cape Spartel, the Battle of Cape St Vincent (where she was Admiral John Jervis’s flagship), and finally, against a combined Franco/Spanish fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar, where she suffered the highest British casualties with 51 of the 800+ crew killed aboard, including Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, who was shot at the height of the battle and died after receiving news of victory, as well as a further 11 seamen who later died of their wounds.

A national appeal saved Victory for posterity some 97 years ago, after which she was placed

HMS Warrior

The world’s fastest, largest, most powerful warship when launched in 1860, the steam- and sail-powered HMS Warrior never fired a shot in anger. Rather, her reputation and obvious supremacy intimidated enemy fleets and deterred them from attacking. HMS Warrior was the pride of Queen Victoria’s fleet, Britain’s first iron-hulled, armoured warship sporting iron sides for protection against exploding shells and large guns – a combination that changed naval warfare. The Royal Navy had been determined to design an invincible ship, and her armament, size, and speed had a profound effect on naval architecture. Nevertheless, Warrior’s warship career was shortlived: within a few years she was obsolete, replaced by faster designs with bigger guns and thicker armour. By 1871, she was downgraded to coastguard and reserve services, put up for sale as scrap in 1924, then converted into a floating oil pontoon at Pembroke Dock. After the oil depot closed in 1978, Warrior became the world’s largest-ever maritime-restoration project under the Maritime Trust before returning in 1987 to Portsmouth Harbour, where she now occupies a gateway position as a ship museum and monument.

HMS Warrior was Britain’s first iron-hulled ship, and as such, the pride of Queen Victoria’s Royal Navy fleet.

Photo by Bennett Via Wikimedia Commons

In 2017, she came under new ownership on April 1 following the Warrior Preservation Trust’s merger with the National Museum of the Royal Navy, which owns HMS Victory and First World War monitor, HMS M.33. The completion of a £4.2-million upper-deck conservation programme was celebrated on July 12, 2019, when the ship was presented as she was during the Round-Britain tour of 1863, and now even more of this historic warship is open for visitors to explore.

HMS M.33

Youngest of the four maritime ladies welcoming HMS Prince of Wales to Portsmouth is HMS M.33,

One of only three British surviving warships from World War I, the floating gun platform HMS M.33 saw action at the Battle of Gallipoli in 1915.

Photos by Megan Michell

The sole British survivor of the 1915-16 Dardanelles Campaign (and Russian Civil War that followed). M.33 is one of just three existing British World War I warships. She was a floating gun platform, whose first operation was at the Battle of Gallipoli in August 1915, the year in which her keel was laid down. Her shallow draft permitted her to approach close inshore and fire her two powerful six-inch guns. The rest of the war was spent in the Mediterranean, where M.33 was involved in seizure of the Greek fleet at Salamis Bay in 1916. Before returning to Portsmouth to become a mine-laying training ship (renamed HMS Minerva), she had been sent to Murmansk in Russia after the war to relieve the North Russian Expeditionary Force. World War II saw the vessel serving as a floating staff office; after her boilers and engines were removed she was converted to a boom defence workshop and later served as a floating workshop at Royal Clarence Yard in Gosport. Since 1997, M.33 has sat beside HMS Victory in No.1 Dock in Portsmouth Historic Dockyard, where she was part of the Great War at Sea 1914-1918 programme, and where she was opened in 2015 in time for her centenary to be celebrated.