8 minute read

LIFE ON THE ISLAND

BY DAVID STEELE

THE SITE FOR THE MOST LEGENDARY BATTLE IN MARINE CORPS HISTORY WAS A DAMP, DESOLATE, VOLCANIC ISLAND THAT REEKED OF SULFUR. LIFE AS A FIGHTER OR NONCOMBATANT WAS DREARY, FRIGHTENING, HEROIC – AND SOMETIMES HUMOROUS.

Cold. Damp. Desolate. Wretched. Smelly. Godforsaken. An entire Roget’s Thesaurus of unpleasant adjectives has been used to describe Iwo Jima. They’re appropriate depictions, even without the horrors of war. Add the fury of unrelenting attacks by a fanatical enemy, and it’s not surprising that those who were on Iwo in February 1945 vividly recall it as 8 square miles of living hell.

From landing to departure, Marines of the 4th and 5th Divisions were on Iwo for slightly more than a month. Relatively few individuals, however, actually spent the entire 36 days on the island, because few of the initial landing troops survived unscathed. Whether they remained for hours or weeks, however, the experiences left indelible impressions on every man who set foot on Iwo Jima.

What was it really like to be there? Here are glimpses into a life that no one likes to remember, but no one can forget.

It was always too cold on Iwo, except when it was too hot. The temperature might drop into the 40s with rain during the day, and Marines would shiver in a foxhole or bomb crater night after night. Sometimes, though, the foxholes could be uncomfortably warm, with the Earth temperature hitting 100 degrees.

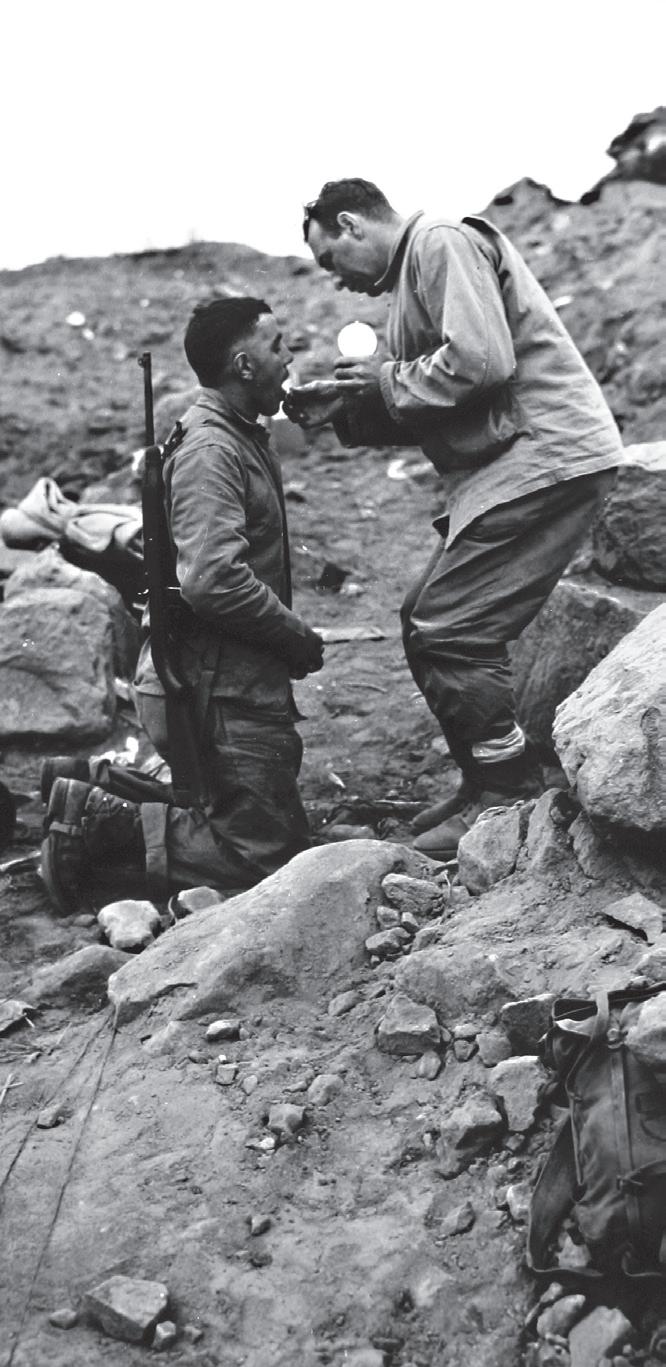

Father Joseph Hammond gives Holy Communion to a 4th Division Marine on Iwo Jima, Feb. 27. 1945, even as the battle rages on.

MARINE CORPS HISTORICAL CENTER PHOTO

This heat could be useful. Some foxholes hit sulfur steam vents and Marines discovered they could warm their C-rations in them. But it took the care of a gourmet chef to get the cooking time just right – even a few extra seconds of heat could turn a hot meal into an exploding mess.

During the early days of the invasion, Marines were warned to preserve their water since there were no natural supplies on Iwo. The only wells were cisterns built by the Japanese to collect rainwater. Eventually desalination units were erected, but with thousands of men to serve, water was always in short supply. Shaving and bathing, even with cold helmet water, was a luxury.

It was even worse for the Japanese, particularly after Marines captured the cisterns located about halfway up the island. The defenders had stored about a month’s worth of supplies in caves and pillboxes, and the few captured Japanese invariably talked of troops who were continually thirsty and malnourished. In desperation, they’d venture out of their caves at night to sneak through Marine lines and forage for essential supplies.

From many accounts, it appears that the most-often used word on Iwo Jima was “Corpsman!” Certainly among the most courageous men on this, or any other battleground, were those who gave fallen Marines their first vital medical aid, often in the midst of hostile fire.

In fact, medical personnel often earned the most decorations in their units. They also took the most casualties, because corpsmen were among the favored targets of Japanese gunners, as were the litter bearers who carried the injured back to aid stations and the beach. That’s why the term “noncombatants” typically appears in quotation marks in various Iwo histories.

Marines had no shortage of derogatory words to describe the day-to-day life on Iwo Jima. With most of their time spent dislodging a tenacious and fanatical enemy, mundane moments like making a cup of coffee (seen here) were a welcome thing. Here, two Marines use a hot sulfur spring as a heating device.

MARINE CORPS HISTORICAL CENTER PHOTO

Quite simply, no one on Iwo escaped combat, even if they never used a weapon. Yet countless lives were saved because these men did their job so well under such adverse conditions.

For example, one of the first makeshift surgical amphitheaters on Iwo was located in a 15-foot crater created by a 16-inch naval shell during the preinvasion bombardment. Niches were carved from walls to accommodate the wounded, and two larger platforms were sculpted as operating tables. This temporary operating area accommodated 16 wounded below ground level.

Unlike several other locations, this site didn’t take a direct hit. One time, though, a Marine was blown into the crater, landing on a patient being sutured.

Many bodies were mangled so badly by explosives that the only way to distinguish them as Marines was by the leggings they wore. Other injuries were simply, painfully bizarre. One Marine shattered all the bones in his feet, without the skin being broken, when a satchel charge blew up under his tank. Another awoke to discover he couldn’t pry his feet apart. The surgeon, seeing an entry wound in one foot but no exit wound, finally determined that the crossed feet had been “nailed” together by a spent .30-caliber bullet.

Among the most terrifying of all the weapons used against the Americans was the “spigot” mortar. It was a 5-foot-long, 13-inch-wide projectile whose flight could be followed like some gigantic ash can, speeding through the air. It was notably inaccurate for hitting a specified target. But it was terribly lethal as well, sending out pieces of shrapnel that could be several feet long. Another deadly part of the Japanese arsenal was the knee mortar. A soldier could fire it once or twice, then quickly shift to a new position before being located.

Perhaps, though, as many Marine casualties were caused by the weapons of close-in combat – grenades, small arms, and swords – as any other. The Japanese had vowed to conduct a guerrilla war, and they did it well. Attackers would suddenly emerge from caves as human bombs, blowing up themselves and those around them with satchel charges. Infiltrators would silently creep up to Marine foxholes, then roll grenades down the sides. And, using captured U.S. uniforms, saboteurs might lie in wait for hours to cause maximum devastation.

Grim as this supply container might seem, its contents undoubtedly saved some lives.

MARINE CORPS HISTORICAL CENTER PHOTO

Surgeon James Vedder recalls accompanying a line officer as he did a reconnaissance on a supposedly just-secured plot of land. The two men walked past a body covered by a Marine poncho, then the officer wheeled around and fired into the poncho. Underneath was a Japanese soldier, a bag of grenades clutched to his chest.

“All of the Marines in this sector were accounted for,” explained the officer to a quizzical Vedder. Therefore, the hidden body had to be an unfriendly ambusher just waiting to strike.

Sentries and patrols, including some with canine support, were used to counter the nightly infiltrators. So, like a mantra, Marines chanted the day’s passwords to avoid friendly fire as they returned to their own lines or simply made a midnight nature call. Today’s passwords might include the names of U.S. cities; tomorrow’s might be U.S. cars; the following day’s, U.S. presidents.

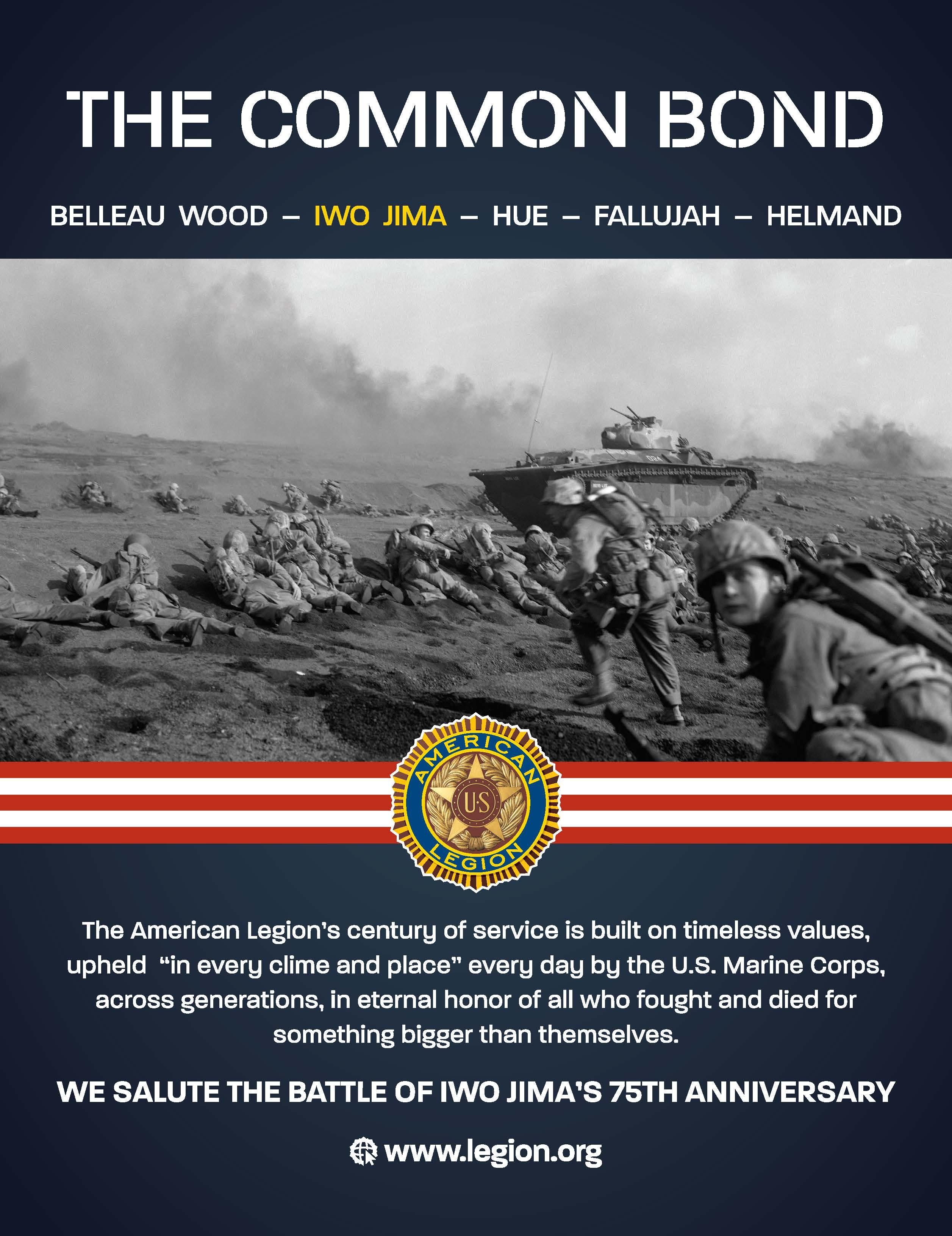

Advertisement

Naturally, the tension could lead to mistakes and occasionally a lighter moment. “Password?” challenged one sentry. “Wallace, Wallace, Wallace,” responded a startled Marine.

“Not vice presidents … presidents!” hissed the sentry.

Amid all the mind-numbing horror, there were other stories destined to elicit a much-needed laugh both then and in the re-telling over the years. For example, a Marine officer awakened one morning to find that a Japanese soldier had shared his foxhole the entire night. They both leaped out in amazement, running in different directions. “Why didn’t you shoot him?” asked a buddy hearing the story.

A Marine inspects a Japanese 320mm mortar shell (without warhead) still partially resting on the fallen spigot mortar’s base plate. Other sections, bodies, and heads are in the right recess of the position. Fully assembled, the mortar shell weighed 675 pounds and was 5 feet tall. Gen. Robert E. Cushman, Jr., 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines commander at Iwo Jima and later a Commandant of the Marine Corps, said, “You could see it coming, but you never knew where the hell it was going to come down.”

MARINE CORPS HISTORICAL CENTER PHOTO

“It’s not right to shoot someone you just slept with,” explained the officer.

Stretcher bearers bring in a wounded Marine while under sniper fire near Motoyama Airfield No. 2. Corpsmen and stretcher bearers were among the favorite targets of the Japanese.

MARINE CORPS HISTORICAL CENTER PHOTO

One morning, Marines near one of the airfields noticed a bulldozer leveling the ground. As with any vehicle on Iwo, it drew a lot of unfriendly sniper fire. But two ingenious Seabees figured a way to improve their chances. As the bulldozer reached the airfield’s end, a Seabee appeared from a foxhole, jumped aboard the driverless vehicle, headed it in the opposite direction, then scampered back into hiding. At the other end of the field, a second Seabee repeated the process until the job was completed.

Mail calls became a much-appreciated morale booster for troops who hadn’t heard from home for weeks. They, too, could provide a moment of humor. At his first mail call, Vedder got a letter from the Naval Bureau of Medicine and Surgery noting that he hadn’t completed some required correspondence courses. A stern warning followed: If these courses weren’t completed immediately, Vedder would be transferred to “more hazardous duty.”

As Vedder tried to picture more hazardous duty than Iwo Jima, the other medics chuckled and asked if they might join him.

There were also moments of normalcy conducted in surreal settings. Chaplains had crawled up Iwo’s terraces and hills along with the infantry. They conducted services when and where possible: the Protestants might meet in a spigot mortar crater; Catholics by wrecked enemy anti-aircraft guns. Attendance was always good.

A Marine tends to the grave of Gunnery Sgt. John Basilone, who received the Congressional Medal of Honor for actions at Guadacanal. He died while leading an assault at Iwo Jima.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO

Even as the battle raged, division cemeteries were created on Iwo. Here, too, noncombatants tried to do their depressing work under the never-ending threat of enemy fire. Sometimes there were so many men to be buried at one time that long rows of graves were dug and, following brief services, covered en masse with bulldozers. Eventually, more than 5,000 American fighting men would be interred on Iwo Jima. Years later these cemeteries would be closed and the bodies returned to the United States. But no Marine, medic, or Seabee who walked – or was carried away – from the island in 1945 would ever forget those left behind.

Nor would they forget how razor thin the line was between surviving and perishing on Iwo Jima. In what could be a testament for all those who came home, one private said simply to a friend who asked him what it was like on the island, “I’m alive.”