2 minute read

The NOAA Diving Program

By Craig Collins

On the website of NOAA’s Marine Debris Program, a video from 2014 shows two NOAA divers, somewhere in the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in Hawaii, patiently free a young green sea turtle hopelessly tangled in an abandoned fishing net. The one-minute clip has a happy ending: the liberated turtle swims away into the turquoise waters.

The divers belonged to a team of 17, sent to remove marine debris from the World Heritage Site. The dive team, in the course of removing 57 tons of derelict nets and plastic litter from the World Heritage Site, found and freed three turtles.

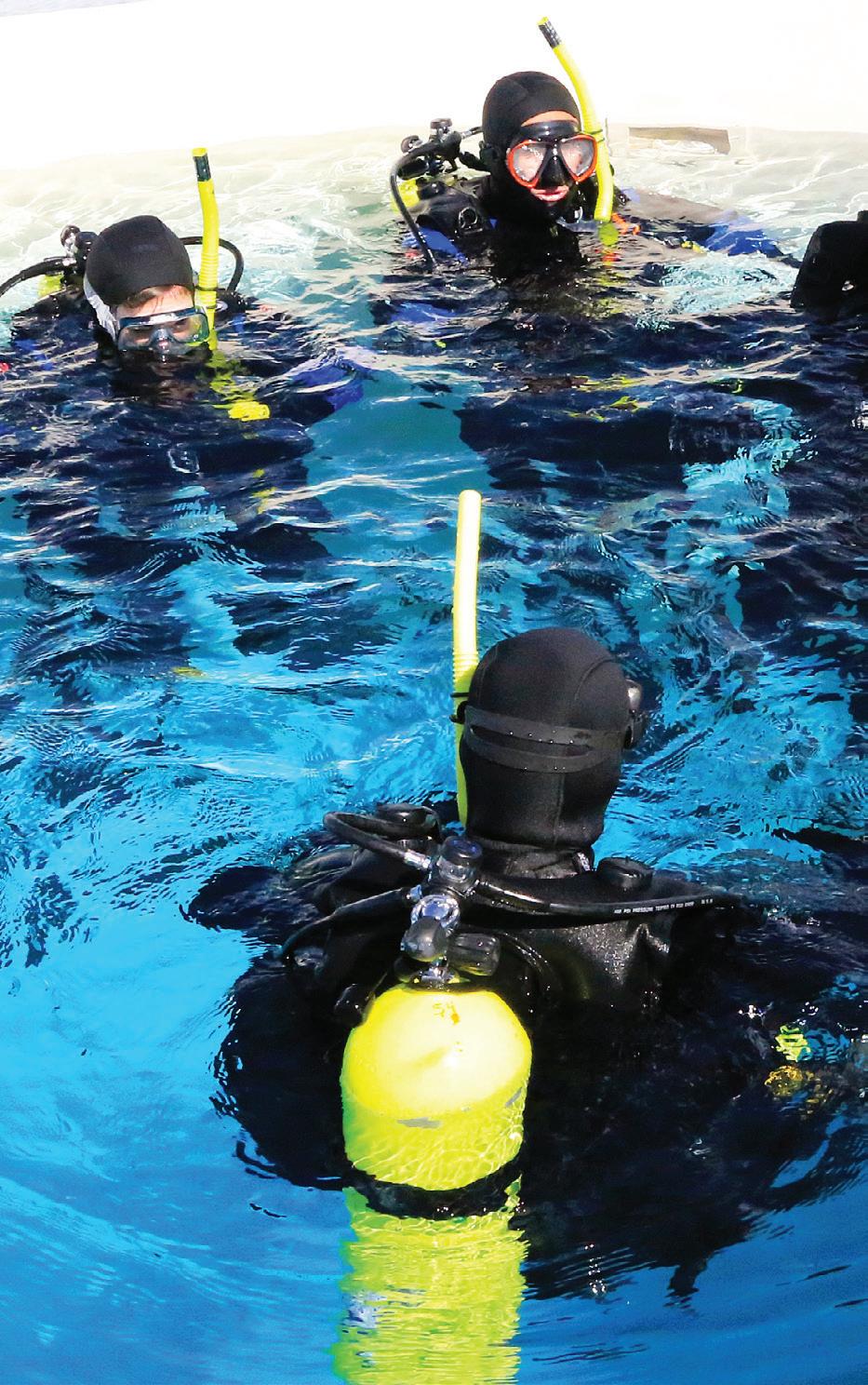

NOAA Diver students and a NOAA Diving Center (NDC) instructor prepare to descend into the NDC training tank to complete a check out dive.

When you work in the ocean, as many NOAA people do, sometimes you need to dive. You may need to dive a lot, actually – over the past five years, NOAA divers have averaged about 12,000 dives a year. The vast majority of these are scientific dives in support of NOAA’s mission of science, service and stewardship; while NOAA dives are conducted for each of the agency’s six line offices, most are performed for either the National Marine Fisheries Service (NOAA Fisheries) or the National Ocean Service (NOS). Mostly NOAA divers help to conserve and manage coastal and marine ecosystems and resources, though they do much more, from installing mooring sites in National Marine Sanctuaries to maintaining ships, sensors or buoys. OMAO facilities and aboard NOAA research vessels.

Curious dolphins enter the area within a diver’s reef visual census survey in St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands.

The program’s training hub and administrative headquarters are at the NOAA Diving Center (NDC) in Seattle, Washington, where instructors train and certify scientists, NOAA Corps officers, engineers and technicians to carry out NOAA diving operations. NDC provides year-round training opportunities to these and other federal, state and local government employees whose jobs require them to dive. These instructors also travel to NOAA diving units around the country to offer individualized training. In the winter, when Seattle weather and temperatures aren’t diver-friendly, NDC offers various courses in Florida.

The program has a diving medicine component dedicated to training and preparing divers, dive masters, and field medical personnel to become first responders in case of barotrauma events or other emergencies. Courses for diving medical technicians and physicians are also offered at the Diving Center.

Cmdr. Eric Johnson conducting a dive in Hawaii during his time aboard NOAA Ship Hi’ialakai.

To increase the scope and impact of their work, NOAA divers often work with partners from other agencies, research institutions or private foundations (i.e., the University of Hawaii, the American Academy of Underwater Sciences; the Alaska Department of Fish and Game). Only partners who have “reciprocity” agreements in place can send “reciprocity divers” to work with NOAA divers. These reciprocity agreements, managed by the Diving Program, assure all divers are following NOAA diving safety standards and procedures and are properly equipped.

NOAA Diver Shay Viehman (left) and her National Park Service (NPS) colleague Lee Richter aboard an NPS vessel during National Coral Reef Monitoring Program surveys in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

From the pristine waters of a protected marine area to murky, congested coastal harbors, NOAA divers work in a variety of conditions to meet a variety of missions: keeping coastal communities safe, keeping shipping lines navigable, maintaining the health of fisheries; monitoring and restoring coral reefs; and installing buoys that help recreational divers find their way within our National Marine Sanctuaries. Any underwater effort that requires NOAA expertise is likely performed by NOAA divers, working under the guidance and supervision of the NOAA Diving Program.