13 minute read

MARSOC: An Agile Force Adapts to New Challenges

MARSOC

An Agile Force Adapts to New Challenges

BY J.R. WILSON

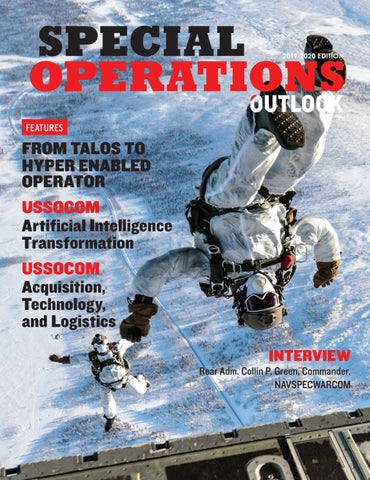

Marines with 1st Marine Raider Support Battalion and Operational Detachment- Alpha Special Forces soldiers conduct movement to a landing zone for a low altitude resupply drop at Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center, Bridgeport, California, Aug. 5, 2018. The purpose of the training was for Army Special Forces and MARSOC to improve upon their joint training techniques.

Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command (MARSOC) was born in 2006 as the Corps’ dedicated special operations unit and their component of the U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM), fighting an asymmetric war on two fronts – the deserts of Iraq and the mountains of Afghanistan. As the U.S. military commitment to those two countries has declined, MARSOC has begun retailoring itself for future conflicts worldwide, possibly including peer-to-peer combat for the first time since World War II.

Their guidebook for this evolution, issued in March 2018, is q MARSOF 2030. It is the goals and requirements statements by which MARSOC will determine the best unit compositions, training, equipment, concept of operations (CONOPS) and tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) for any conflicts in which they may engage or other deployments.

“The future operating environment will challenge MARSOC in the same way that warfare has challenged militaries throughout history. However, the pace of change today is accelerating exponentially. The interplay of technological innovation, global demographic shifts, challenges to the post-WWII world order and the rise of both state and non-state powers portend a future operating environment that is increasingly uncertain, volatile, and complex. The degree to which MARSOC will contribute to our nation’s future defense will depend on its ability to recognize and adapt to the challenges of the future operating environment,” the document states in its introduction.

“We’ve really come up with a vision in continence with SOCOM, looking at the applicability of SOF. Our vision – MARSOF 2030 – gives us a roadmap of innovation pathways we need to be relevant in an operating environment that continues to change,” said Maj. Gen. Dan Yoo, who took command of the Marine Raiders organization about six months after MARSOF 2030 was issued.

“There is a lot of work to do to implement some of those things. As a relatively new component – we just had our 13th anniversary – and as we move forward, it gets back to the daily challenge you have in force deployment as well as force development and, more importantly, force design, which is where 2030 takes us. The cognitive Raider is the centerpiece of that, how we select, train, and educate on deploying forward into the different environments.”

An additional 368 personnel will be added to MARSOC through October 2022 to bring the command to its full authorized size. Yoo said he does not see any need to expand MARSOC beyond that number, noting, “It’s not about the numbers, but the capabilities.”

“We’re continuing to evolve our Raider training center, where we certify spec ops officers and critical skills operators and spec ops-capable specialists, increasing the advanced courses associated with that. As resources, from a monetary perspective, get reduced, we’re trying to turn training into a joint venue and bring in coalition and interagency and conventional forces and replicate as much as possible what we will see downrange,” he explained.

“This year we’re bringing in the next 50 new Raiders in combat support and combat service support and integrating them into the formation. That is the first draw of 368. We’re also looking at flexible deployment models to build readiness. By 2025, we’re trying to get to the cognitive Raider with a better model where we’re doing force development, as well as some efficiencies on force posture.

“Our base unit of action is the Marine Special Operations Company, about 125 individuals across multiple functions and led by a major. Compared to our fellow SOF components, it is what the Army would put out as an AOB [Advanced Operational Base]. We have the ability to add on to that, and one thing we’re looking at is putting out hyperenabled teams, about 14 individuals with some of the enablers across different disciplines, so we have a very flexible unit of action that can go forward.”

Yoo believes there are a number of advantages to MARSOC’s size – the smallest of the four service SOF components of USSOCOM.

“From a component level, we’re a very flat organization. We have a little more than 200 civilians and active-duty personnel in my headquarters. About 80 percent of the whole component is available for deployment,” he noted. “So we can turn and focus on problem sets we’re tasked by SOCOM much more agilely than some of the other SOF components. Having a flatter command and control organization, the ideas are both bottom-up and top-down driven.”

Marine Raiders from Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command (MARSOC) K-9 Unit, along with Naval Air Station Key West’s Search and Rescue Team, conduct helicopter casts in Truman Harbor during the special operations command’s multipurpose canine handler training.

U.S. Navy Photo By Danette Baso Silver

That provides MARSOC with the flexibility to make changes quickly and efficiently – as listed in MARSOF 2030 – as one of four core pathways of innovation, along with MARSOF as a connector, combined arms for the connected arena, and the cognitive operator.

“Each of the pathways are individual concepts capable of standing alone; however, they are interrelated and mutually supporting,” according to the document. “The pathways are multifaceted and represent a range of ideas; many of the possibilities are as yet undiscovered. These concepts represent the ‘what’, conceptual visions which can provide MARSOC distinct value in the future operating environment.

“None of the innovation pathways are necessarily ‘end state’ oriented as much as they each create a broad field of opportunity. The ‘how’ will be a greater challenge. Implementing these concepts to achieve concrete capabilities will require time, effort, resources and flexibility. We must recognize the connection between these concepts and programmatics. This will require leveraging both USMC and USSOCOM capability development mechanisms.”

According to MARSOF 2030, “the consequences of the information environment relate to how it affects the cognition (perceptions, beliefs, decisions, etc.) of its relevant actors.”

“Our units must be able to thoughtfully combine intelligence, information, and cyber operations to affect opponent decisionmaking, influence diverse audiences, and counter false narratives. Furthermore, we must be able to synchronize operations, activities and actions in the information environment with those across operational domains and, when necessary, fuse cognitive and lethal effects. Given current trends, effects in the information environment will become increasingly decisive across the conflict continuum.” That is where the cognitive Raider comes in, the report continued. “Sharp regional competition by adversaries with the ability to mitigate or deny traditional U.S. military strengths will increasingly drive missions demanding a high degree of skill and nuance to discern the sources of the problem and develop meaningful solutions. These problems will strain current conceptions of conflict and joint phasing, thus requiring SOF capabilities that can effectively address them while minimizing open hostilities.

Marines with 1st Marine Raider Support Battalion post security during a medical evacuation exercise at a training area in Hawthorne, Nevada, during Training Readiness Exercise II, July 28, 2018.

U.S. Marine Corps Photo By Staff SGT. Joseph Sanchez

“The Raiders we send into such environments must be able to understand them and then adapt their approaches across an expanded range of solutions. While tough, close-in, violent actions will remain a feature of future warfare, MARSOF must increasingly integrate tactical capabilities and partnered operations with evolving national, theater, and interagency capabilities across all operational domains, to include those of information and cyber.”

That effort will emphasize the plan’s goal for enterprise-level agility, using MARSOC’s small force as an advantage to rapidly re-orient to confront new challenges as they emerge.

“The unity of purpose and organizational dexterity over which MARSOC presides provides SOCOM with an agile, adaptable force to meet unexpected or rapidly changing requirements. Seen from the bottom up, forward-deployed Raider echelons are able to reach directly back into a responsive component command headquarters to assist in innovating solutions for operational problems,” the report stated. “The results of our wargames are in line with most of the future operating environment assessments that forecast increasing uncertainty, volatility, and complexity … An institutionally agile MARSOC provides USSOCOM with a component that can rapidly orient, focus, or retool capabilities to meet emerging requirements or work a discrete transregional problem set with full-spectrum SOF from onset through resolution.

A Critical Skills Operator with 1st Marine Raider Battalion participates in horsemanship training as a part of the Special Operations Forces Horsemanship Course aboard Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center, Bridgeport, California, June 20, 2018. The purpose of the advanced horsemanship course is to teach the special operations forces (SOF) personnel the necessary skills to enable them to ride horses, load pack animals, and maintain animals for military applications in remote and dangerous environments.

U.S. Marine Corps Photo By Lance CPL William Chockey

“In realizing this vision, MARSOC will remain true to its Marine Corps values and warrior ethos, while simultaneously challenging its own organizational culture and service paradigms. Mere declarations of agility will be insufficient to achieve this vision; MARSOC will have to examine processes, assess emerging requirements and adapt capabilities across DOTMLPF [Doctrine, Organization, Training, Materiel, Leadership and Education, Personnel, Facilities] to achieve a capability that currently resides in only one area of the SOF Enterprise. Unity of purpose and effort, as well as a shared identity as Marine Raiders, provide MARSOC with the institutional resiliency to pursue new constructs and approaches that optimize capability, flexibility, versatility, and adaptability. This new level of agility and adaptability also requires willingness and the processes to critically assess performance, internally identify flaws, and make the necessary corrections. MARSOC may provide singular value to USSOCOM by actively striving to be its most agile, adaptable and responsive component.”

For Yoo, MARSOF 2030 outlines a natural progression of MARSOC, reflecting changes occurring throughout the Marine Corps and other services as well as within SOCOM and its Army, Navy, and Air Force components.

“As you look at the four pathways, MARSOF has a connector with combined arms. The focus as we move forward is the cognitive Raider and providing training to those individuals,” he said. “The area we’re focusing on is interoperability, the global combatant commands, and other non-kinetic capabilities in the combined arms connected arena, which have not been traditional parts of military effects.”

MARSOC also is looking to SOCOM, the “Big Corps,” and the Navy to provide access to the latest technologies and advanced equipment, from communications and cyber warfare to battlefield transport and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR)-capable unmanned platforms. Again, MARSOC’s small size could serve as an advantage, making acquisition, training, and implementation of developing technologies far easier than is typical for the larger organizations.

“We’re trying to ensure we have access to those new systems [including] machine learning and AI [artificial intelligence] as we go forward to access information no matter where you are and work in a degraded comms environment; semi-autonomous capabilities; Group 2-level UAS – something more expeditionary and long duration that doesn’t need a runway,” Yoo said.

“As we bought equipment, there are some things we off-ramped, such as the large MRAP and other heavy vehicles, relying on some of the new GMVs [ground mobility vehicles] coming in and buying just what we need to train with and outfit units going forward. We want to increase our equipment sets so there is more stability in units without having to share. We’re also involved in the development of new technologies.”

U.S. Marine Corps Raiders with the 3rd Marine Raider Battalion ride in a 1st Special Operations Support Squadron watercraft at Eglin Range, Florida, May 30, 2018.

U.S. Air Force Photo By Senior Airman Joseph Pick

In the coming years, new, far more size, weight and power (SWaP) – reduced technologies also will continue to evolve the individual Raider and small units into increasingly advanced, self-contained warfighters across fronts never before possible.

In the late 1980s, when the world and war were a different place, an Army Special Forces colonel said, “If you want to kick down doors and kill people, call the Marines; if you want to teach others how to kick down doors and kill people, send in the Green Berets.” While both Big Corps Marines and Green Berets are far more sophisticated in their skills and abilities today, the Raiders rapidly are becoming something only imagined in science fiction not so long ago.

When asked if he sees a greater MARSOC reliance on wearable electronics, including direct individual Raider control of remote devices and electronic warfare/cyber warfare equipment and training, for example, Yoo replied:

“Everything is leading that way. From the cognitive Raider to the hyper-enabled team SOCOM is looking for, each individual team member, yes. We’re also working with SOCOM and the Marine Warfighting Lab on autonomous and semi-autonomous air and ground vehicles for resupply, medevac, weapons, etc. We’re already utilizing quad copters, but need autonomous vehicles to go into tunnels and assisted learning/machine learning to access and share the vast amount of data that’s out there.

“Awareness of the vulnerabilities we have in the virtual domain we’re in means everything you do has significant [electronic] profiles out there. We’re doing some things with MARFORCYBER [Marine Corps Forces, Cyberspace Command] and U.S. Cyber Command. In the future, every operator will be a cyber specialist. The cognizance of everyone in the information environment about the vulnerabilities that exist is critical.”

Commandant of the Marine Corps Gen. Robert B. Neller and Commander of U.S. Marine Corps Forces, Special Operations Command, Maj. Gen. Daniel D. Yoo view the Memorial Wall etched with the names of fallen Raiders after MARSOC’s 13th Anniversary Ceremony at Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, Feb. 21, 2019. The organization has paid a high price for the victories it has achieved. The youngest and smallest component of the DOD’s special operations forces, MARSOC has lost 43 souls in combat and in training, including two multipurpose canines.

U.S. Marine Corps Photo By SGT Olivia Ortiz

While the military as a whole is restructuring to follow the Department of Defense’s (DOD) shift of focus from Southwest Asia and Europe to the Asia/Pacific, Yoo said that will have little effect on MARSOC.

“As Marines and Raiders, we never lost our focus on Asia. We’ve been supporting global ops, primarily in the Central Command arena and Africa, but we have 500 operators in 18 countries, many of them in the Indo-Pacific, in support of our partners out there. When you talk about what other regional powers are looking for, our engagements in support of our national objectives and diplomatic relationships, the forces we have there facilitate those. The five potential threats in the national defense strategy are all there. China, for example, is a global competitor. So you can still affect decision-making in support of U.S. objectives whether you’re in that region or not.

“The support we’re providing Africa right now is not and will not change in the near term. There are 54 countries on that continent, each with their own say in the kind of support they need. For MARSOC, the support we have there will remain consistent. I don’t think there will be any major increases [for MARSOC] in one region or another. We’re a global force.”

MARSOC retains as its fundamental structure the Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF) construct, despite having no organic aviation component. For that, it relies on other parts of the military, although it could be said their increasing use of UAVs might be considered a 21st century aviation capability.

“If you look at SOCOM in general and what is required for air support, it is hard to get the same level of support on the West Coast as the East. We get good support for interoperability here because of our location [Camp Lejeune, North Carolina]. As far as owning our own SOF-capable platforms, there is a shortfall. We try to deal with that in dealing in a joint environment with our fellow SOF components.

“Right now – and everybody is measuring unmanned aerial systems [UASs] with what we currently have in the inventory – the Stalker has been an evolutionary process. That has gone very well since the initial deployment about a year ago. The Big Corps also is procuring those. Having those ISR platforms has proved out very well for us in terms of support for our deployed teams.”

The record-setting combat period in South West Asia – and the subsequent drawdown – have negatively affected retention and recruitment across the military – and brought claims of reduced quality of recruits in some areas – but MARSOC stands out as a notable exception. However, Marine special ops has yet to include a female operator since the Pentagon’s change in policy regarding women in combat.

“Retention is exceptional, probably better than the Corps at large,” Yoo said. “And recruiting has been very good. In our last class, we had 31 officers and 161 enlisted. Our capacity to get through that is 120, so recruiting has been very, very good. We’re getting everyone from aviation specialists to communications to intel who want to be part of this formation.

“If anything, quality has gone up as we institutionalized our schoolhouse and turned it into an MOS-producing school. The female who made it through phase one and phase two last year was one of 24 – her and the rest males – who were dropped because they did not meet the metric based on the indicators we have found will predict success based on four or five years of collecting data on individuals who have graduated and gone into teams as members of a successful deployment.”

Three more women are scheduled to make the attempt during the spring, summer, and fall assessment and selection processes this year.

While Yoo, who has been with MARSOC since its inception, believes what has been achieved to date is “truly impressive,” he sees the future of SOF in general and MARSOC in particular to be one of increasing value and utility to DOD and the nation as a whole.

“SOF at large – and MARSOC specifically – is a relevant force, whether counterterrorism or the regional challenges we have out there. I honestly believe SOF is a contact and blunt force. You have to get out there, forward deployed on a regular basis, building capacity and supporting allies and being able to provide options for military leaders going forward. SOF is a huge force multiplier for governmental and interagency collaboration in the Pacific, CENTCOM, and AFRICOM. Look at where we‘ve been helpful in the Pacific, such as the height of the counter-ISIS fight in the Philippines, allowing nations in CENTCOM to restore their sovereignty and in Africa allowing nations to build capacity to maintain security and stability,” Yoo said.

“The need for SOF in the future will be as relevant as it is today; quite honestly, more relevant due to the significance of a small footprint. There are coalition partners as reliant on China or Russia as they are on the U.S. for trade, for example, so having a small unit to support their military needs is less provocative when you compete below the threshold. As we start cyber and info ops more as the norm rather than an afterthought, such small, less intrusive support will help enable countries to deal with problems on their own. The Philippines was an example of that, understanding the political sensitivities and allowing them to take care of their problems with advice and assistance to enable ops.”