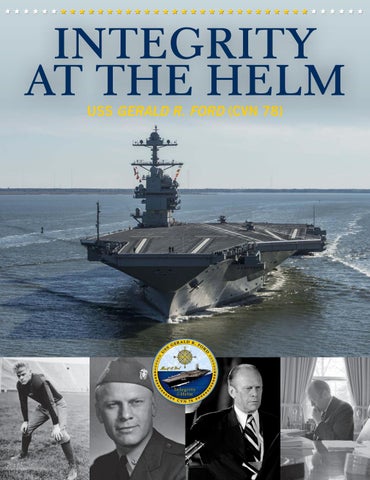

INTEGRITY AT THE HELM USS GERALD R. FORD (CVN 78)

MITIGATING RISK IN DIFFICULT ENVIRONMENTS. For any organization that must deploy equipment, secure critical infrastructure and protect people, assets and workflow - locally or worldwide: BH Defense translates advanced military technologies, security solutions and cyber defenses into strong risk-mitigation plans and “on the ground” results.

GOVERNMENT SERVICES

WHY CHOOSE BH DEFENSE

PLANNING PLUS EXECUTION

ALREADY WHERE YOU NEED US

100% SUCCESSFUL PAST PERFORMANCE

DEPTH OF EXPERIENCE

TECHNOLOGICAL EXPERTISE

CUSTOM SOLUTIONS FROM PRECONFIGURED COMPONENTS

ABILITY TO BUILD FROM ZERO

ENTIRELY VENDOR-NEUTRAL

ISO CERTIFIED

OIL & GAS PRODUCTION AND STORAGE

We attack your risks before they attack your success.

AMANDA CORDANO, BH DEFENSE, LLC, 233 EAST BAY STREET, SUITE 1010, JACKSONVILLE, FL 32202

844-266-7775 ACORDANO@BHDEFENSE.COM WWW.BHDEFENSE.COM

TRANSPORTATION

INFORMATION & COMMUNICATIONS

WATER & ENERGY

POWER GRID

FIELD MEDICAL

FINANCE & BANKING

SETA DRONES SECURITY ADVANCE WEAPON SYSTEMS

CONSULTING

LOGISTICS SUPPLY CHAIN PROJECT MANAGEMENT CONSTRUCTION TRAINING

TRANSPORTATION

INTEGRITY AT THE HELM USS GERALD R. FORD (CVN 78)

WE PROUDLY SUPPORT THE MEN AND WOMEN SAFEGUARDING OUR FREEDOM. The Navy Exchange is extremely proud to celebrate the historic commissioning of the USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78).

“I

n my life, I’ve received countless honors. But none was greater than the opportunity to wear the uniform of lieutenant commander in the United

States Navy. On an aircraft carrier in the South Pacific during World War II, I learned to respect, and to rely on, my comrades as if my life depended on them – because it often did. As a World War II veteran, I yield to no one in my admiration for the heroes of Omaha Beach and Iwo Jima. At the same time, I take enormous inspiration from their grandsons and granddaughters who are writing new chapters of heroism around the globe. Thus, it is a source of indescribable pride and humility to know that an aircraft carrier bearing my name may be permanently associated with the valor and patriotism of the men and women of the United States Navy.” – President Gerald R. Ford

Photo credit by Chris Oxley/Hill

As America’s largest company dedicated to industrial automation and information, we’re proud to welcome USS GERALD R FORD CVN 78 as the newest carrier to the US Navy. We’re proud to provide the advanced automation technologies that help make this ship world-class. We salute the men and women whose service protects our national interest.

For more information visit: www.rockwellautomation.com/global/industries/marine/government Copyright © 2016 Rockwell Automation, Inc. All Rights Reserved. AD2015-61

National Security, Made in America.

americanmanufacturing.org

JBT is proud to support the U.S. Navy and to be part of...

Shipboard Mobile Electric Power Plant to service past, present, and future aircraft

... the new CVN 78 USS Gerald R. Ford and the F-35. +1 801 627 6600 - Ogden, Utah USA www.jbtaerotech.com

+44 208 587 0666 - United Kingdom +852 3966 1360 - Hong Kong, China

American Power Kato Engineering proudly supports the US Navy as an established manufacturing partner for surface ship alternators

The employees of Kato Engineering congratulate everyone involved in the design and construction of USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78). We are gratified by the opportunity to manufacture a key component of the EMALS system, continuing Kata’s history of supporting the US Navy.

The USS Gerald R. Ford is the latest addition to a long list of Navy ships with Kato power supply and energy storage equipment onboard. We’re honored to play a role supporting the people who are keeping our country strong.

katoengineering.com The US Navy did not select or approve this advertiser and does not endorse and is not responsible for the views or statements contained in this advertisement.

C O M M I S S I O N I N G

C O M M I T T EE

USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78) Commissioning Committee Ship’s Sponsor

Susan Ford Bales Chairmen Gregory D. Willard • Douglas L. DeVos • Bryon M. Cavaney, Jr. Matrons of Honor Tyne M. Berlanga • Heather E. Devers Honorary Chairman Richard A. Ford (In Memoriam) Honorary Co-Chairpersons Hon. and Mrs. James A. Baker, III; Hon. and Mrs. James Cavanaugh; Hon. and Mrs. Dick Cheney Hon. and Mrs. William Coleman (In Memoriam); Hon. and Mrs. Alan Greenspan Hon. Carla Hills and Hon. Roderick Hills (In Memoriam); Mr. and Mrs. Bob Innamorati; Hon. and Mrs. Henry Kissinger Hon. and Mrs. John Knebel; Hon. and Mrs. Melvin Laird (In Memoriam); Hon. and Mrs. John O. Marsh Hon. and Mrs. David Mathews; Hon. and Mrs. Terrence O’Donnell; Hon. and Mrs. Paul O’Neill; Mr. and Mrs. Leon Parma Hon. and Mrs. Donald Rumsfeld; Lt Gen Brent Scowcroft, USAF (Ret.); Hon. and Mrs. William Usery (In Memoriam) Hon. and Mrs. John Warner; Mr. and Mrs. Sanford Weill; Hon. and Mrs. Donald Winter; Hon. and Mrs. Frank Zarb Mr. and Mrs. Michael Ford; Mr. and Mrs. John Ford; Mr. Steven Ford Commissioning Committee VADM David Architzel, USN (Ret.); Vaden and Susan Ford Bales; Allen Beermann; Tyne and Hector Berlanga; Dan Bitzer Randy Bumgardner; Joe and Donna Calvaruso; Red and Sheri Cavaney; CAPT William Crow, USN (Ret) Ann Cullen and Len Nurmi; Doug and Maria DeVos; Heather and Jeff Devers; Jennifer Dunn; Linda Ermen; Allen Fabijan Jim and Kathy Hackett; Larry Harlow; J. C. and Tammy Huizenga; Dennie Jagger; Ross Jobson; Bre Kingsbury; Stephen Kirkland CAPT Wayne Kruger, USN (Ret.); Gayle Lemieux; Victor Martinez, Hank and Liesel Meijer; FORCM James Monroe, USN (Ret.) Don and Angela Sheets; FLTCM Jon Thompson, USN (Ret.); Steve and Amy Van Andel; Greg and Annie Willard Michael Williams; MaryPat Woodard Maryellen Baldwin, President & CEO, Navy League of the United States, Hampton Roads Ship Sponsor’s Advisory Committee Bryan Moore; Dalton DeVos; David Willard; Eric Ochmanek; Geoff Hummel; George Gigicos; Gina McLanahan; Heather and Jeff Devers; Jennifer Dunn; John Willard; Leon Parma; Lucas Hicks; Matt Bales; Matt Mulherin; Matthew Innamorati; Mike Willard; Rob Hackett; Rolf Bartschi; Sammy Vreeland; Tyne and Hector Berlanga

USS GERALD R. FORD

19

We salute you

The hard-working men and women of Milwaukee Valve salute the USS Gerald R. Ford and its crew.

Milwaukee Valve products have been installed on U.S. Navy warships for more than 50 years – and every platform of U.S. warship and submarine today. From concept and engineering to design and manufacture, our valves utilize the best technologies available to meet the Navy’s stringent requirements. And our legacy as a trusted shipbuilding partner reflects how proud we are to salute, support and protect our warfighters at sea.

www.MilwaukeeValve.com The U.S. Navy did not select or approve this advertiser, and does not endorse and is not responsible for the views or statements contained in this advertisement. © 2016, Milwaukee Valve Company

B OA R D

O F

D I R E CTO R S

Navy League of the United States Hampton Roads Council EXECUTIVE BOARD AND BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chairman of the Board CAPT Bill Crow, USN (RET) President and CEO Maryellen Baldwin Executive Board CAPT Christopher “Kit” Chope, USN (RET) – Vice President At Large MajGen Jon A. Gallinetti, USMC (RET) – Immediate Past President CAPT Robert N. Geis, USN (RET) – Vice President At Large Mrs. Julie A. Gifford – Vice President of Membership Mr. John Griffing – Vice President of Development VADM James D. McArthur, Jr., USN (RET) – Vice President of Military Affairs FORCM James “Jim” Monroe, USN (RET) – Treasurer CDR Mark E. Newcomb, JACG, USN (RET) – Judge Advocate FLTCM Jon Thompson, USN (RET) – Secretary

Board of Directors HON David H. Adams VADM David Architzel, USN (RET) CDR Charles S. Arrants, USN (RET) RADM Charles J. Beers, USN (RET) CAPT Robert E. Clark, USN (RET) Mr. Joseph Gianascoli ADM William “Bill” E. Gortney, USN (RET) CAPT Ronald Hoppock, USN (RET) CAPT Cameron Ingram, USN (RET) RADM Jack Kavanaugh, SC, USN (RET) Mr. Kevin F. King CAPT Louis P. Lalli, USN (RET) Mrs. Elizabeth Mayo Mrs. Christina Murray CAPT Michael O’Hearn, USN (RET) LtCol John A. Panneton, USMC (RET) CMDCM Len Santivasci, USN (RET) CAPT Louis J. Schager, Jr., USN (RET)

USS GERALD R. FORD

21

SERVICE. LOYALTY. COURAGE. HONOR.

YOU HAVE WHAT IT TAKES. BECOME A STATE FARM® AGENT.

“Being in the State Farm Agency business is the second best job in the world. Service to your country is the best job. But I find that even though it’s the second best job, it’s kind of like 1 and 1A. I’m proud to do what I do.” – Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force (retired), and State Farm Sales Leader David Campanale

statefarm.com/careers The U.S. Air Force did not select or approve this advertiser and does not endorse and is not responsible for the views or statements contained in this advertisement.

Contents 19 COMMISSIONING COMMITTEE

77 EAGLE SCOUTS CARRY ON FORD’S LEGACY By Ben Pycraft

21 NAVY LEAGUE BOARD OF DIRECTORS 79 COMMISSIONING SPONSORS

INTERVIEWS

96 “WHERE ARE THE CARRIERS?”

48 SUSAN FORD BALES, SHIP’S SPONSOR

By Norman Friedman

62 GREGORY D. WILLARD, COMMISSIONING CO-CHAIRMAN

114 USS GERALD R. FORD AND TOMORROW’S AIRCRAFT CARRIERS

84 MATT MULHERIN, EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, HUNTINGTON INGALLS INDUSTRIES AND PRESIDENT, NEWPORT NEWS SHIPBUILDING

By Norman Friedman

126 DESIGNING AND BUILDING AN AIRCRAFT CARRIER By Edward Lundquist

110 COMMISSIONING CO-CHAIRMAN DOUGLAS L. DEVOS AND PRESIDENT GERALD FORD’S CLOSE PERSONAL FRIEND RICHARD M. “RICH” DEVOS, SR.

136 FORD’S CREW REPRESENTS ALL OF THE NAVY, AND ALL OF THE NATION By Edward Lundquist

134 BYRON M. “RED” CAVANEY, JR., COMMISSIONING CO-CHAIRMAN

BIOS 28 PRESIDENT GERALD R. FORD 57 CAPT. RICHARD C. MCCORMACK, COMMANDING OFFICER 59 CAPT. BRENT C. GAUT, EXECUTIVE OFFICER 61 MASTER CHIEF LAURA NUNLEY, COMMAND MASTER CHIEF 67 THE SHIP’S CREST 68 COMMUNICATION, COMMISSIONINGS, COMMITMENT The Navy League Supports the Sea Services By Edward Lundquist

Velan congratulates all the hardworking men and women who helped build the USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78).

As a major supplier of valves to Northrop Grumman Newport News and the U.S. Navy for over 60 years, we are proud to design, qualify, and manufacture valves for the lead ship in the Ford class fleet of the United States Navy supercarriers. www.velan.com

Quality that lasts.

Contents 157 CVN 78 DEPARTMENTS By USS Gerald R. Ford Public Affairs

164 THE CARRIER AIR WING: TODAY AND TOMORROW By Eric Tegler

174 CARRIERS IN WAR AND PEACE By Dwight Jon Zimmerman

197 THE JEEP CARRIERS By Dwight Jon Zimmerman

202 AIRCRAFT CARRIER EVOLUTION By Norman Friedman

215 THE PADDLE WHEEL AIRCRAFT CARRIERS By Dwight Jon Zimmerman

218 SCOUT, STRIKE, FIGHT The Birth and Evolution of the Carrier Air Wing By Jan Tegler

234 THE POSTWAR CARRIER REVOLUTION By Norman Friedman

247 THE SEA CONTROL SHIP By John D. Gresham

252 UNDERWAY ON NUCLEAR POWER By Norman Friedman

264 CARRIERS AROUND THE WORLD By Norman Friedman

278 USS GERALD R. FORD PLANKOWNERS

Photosensitive Anodized Aluminum

THE MOST SPECIFIED IDENTIFICATION MATERIAL IN THE US NAVY

Metalphoto® is photosensitive anodized aluminum, specified for durable label plates, placards, instruction plates and UID compliant barcode labels.

Cross Section anodic layer

Metalphoto’s durability comes from its image – which is sealed inside of the anodized aluminum, providing resistance to hydraulic fluids, fuels, salt spray corrosion, sunlight degradation, abrasion, high temperatures and other chemicals.

sealed image aluminum base

Metalphoto® is a Registered Trademark of Horizons Inc.

The manufacturer of Metalphoto® (Horizons Imaging Systems Group) congratulates the men and women of the US Navy on the launch of the USS Gerald R. Ford CVN 78. We look forward to continuing to provide the US Armed Forces with the highest quality material for all their asset identification needs, as we have for the past 65 years.

UID LABELS

VALVE & PIPE MARKINGS

SHIPSETS

DAMAGE CONTROL PLACARDS

WARNING COMPLIANCE

Visit metalphoto.com to receive a data sheet, case study & product sample. For specific application questions, contact Horizons ISG at 877.594.8173 or info@horizonsisg.com.

INTEGRITY AT THE HELM USS GERALD R. FORD (CVN 78)

Published by Faircount Media Group 4915 W. Cypress St. Tampa, FL 33607 Tel: 813.639.1900 www.defensemedianetwork.com www.faircount.com EDITORIA L Editor in Chief: Chuck Oldham Managing Editor: Ana E. Lopez Editor: Rhonda Carpenter Contributing Writers: Norman Friedman, John D. Gresham, Edward H. Lundquist, Ben Pycraft, Eric Tegler, Jan Tegler, Dwight Jon Zimmerman DESIGN AND PRODUCTION Art Director: Robin K. McDowall Designer: Daniel Mrgan Ad Traffic Manager: Rebecca Laborde ADVERTISING Ad Sales Manager: Steve Chidel Account Executives: Benjamin Baugh Chris Day, Art Dubuc, Joe Gonzalez Andrew Moss, Troy Koontz OPER ATIONS AND ADMINISTR ATION Chief Operating Officer: Lawrence Roberts VP, Business Development: Robin Jobson Business Development: Damion Harte Financial Controller: Robert John Thorne Chief Information Officer: John Madden Business Analytics Manager: Colin Davidson FAIRCOUNT MEDIA GROUP Publisher, North America: Ross Jobson Copyright Faircount LLC. All rights reserved. Reproduction of editorial content in whole or in part without written permission is prohibited. Faircount LLC and the Navy League of the United States, Hampton Roads, do not assume responsibility for the advertisements, nor any representation made therein, nor for the quality or deliverability of the products themselves. Reproduction of the articles and photographs, in whole or in part, contained herein is prohibited without written permission of the publisher, with the exception of reprinting for news media use. Permission to use various images and content in this publication was obtained from the U.S. Department of Defense and its agencies, and in no way is used to imply an endorsement by any U.S. Department of Defense entity for any claims or representations therein. None of the advertising herein implies U.S. government, U.S. Department of Defense, or U.S. Navy endorsement of any private entity or enterprise. This is not a publication of the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Navy, or the U.S. government.

P R E S I D E N T

28

CVN 78

G E R A L D

R .

F O R D

P R E S I D E N T

G E R A L D

R .

F O R D

President Gerald R. Ford

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

(July 14, 1913 – Dec. 26, 2006)

USS GERALD R. FORD

29

P R ES I D EN T

G ER A L D

R.

F O R D

According to an ancient tradition, God preserves humanity despite its many transgressions because at any one period there exist ten just individuals who, without being aware of their role, redeem mankind. Gerald Ford was such a man. Propelled into the presidency by a sequence of unpredictable events, he had an impact so profound it’s rightly to be considered providential.

– Secretary of State Henry Kissinger EARLY YEARS Gerald R. Ford, 38th President of the United States, was born Leslie Lynch King, Jr., the son of Leslie Lynch King and Dorothy Ayer Gardner King, on July 14, 1913, in Omaha, Nebraska. His parents separated two weeks after his birth, and his mother moved with him to Grand Rapids, Michigan, to live with her parents. On Feb. 1, 1916, approximately two years after her divorce, Dorothy King married Gerald R. Ford, a Grand Rapids businessman. The Fords immediately began calling her son Jerry Ford, and in 1935, his name was officially changed to Gerald Rudolph Ford, Jr. The future president grew up in a close-knit family that included three younger brothers – Thomas, Richard, and James. Mr. Ford attended South High School in Grand Rapids, where he excelled scholastically and athletically. He was named to the honor society and both the “All-City” and “AllState” football teams. To earn spending money he worked for the family paint business and at a local restaurant. He was also active in Scouting, and achieved the rank of Eagle Scout in November 1927 – the only American president to do so.

COLLEGE YEARS From 1931 to 1935, Mr. Ford attended the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, where he majored in economics and political science, and graduated with a B.A. degree in June 1935. At a time of national economic hardship, he financed his education with part-time jobs, a small scholarship from his high school, and modest family assistance.

Gerald R. Ford’s high school graduation portrait.

OUTSTANDING ATHLETE An extremely gifted athlete, Mr. Ford was a three-year letterman and played on Michigan’s national championship football teams in 1932 and 1933. He was voted the Wolverines’ most USS GERALD R. FORD

31

P R ES I D EN T

G ER A L D

R.

F O R D

Gerald R. Ford on the football field at the University of Michigan (1933).

valuable player. On Jan. 1, 1935, he played in the annual East-West College All-Star Game in San Francisco. That August, he played at Soldier Field against the Chicago Bears in the Chicago Tribune College All-Star Football Game, and his performance led to offers from the Detroit Lions and the Green Bay Packers. In tribute to one of its greatest student-athletes, Michigan subsequently retired Mr. Ford’s jersey number – 48. In addition, he was named to Sports Illustrated’s Silver Anniversary All-America Football Team, received the National Football Foundation’s Gold Medal – its highest honor – and in 2006, was recognized by the NCAA as one of the 100 most influential student-athletes of the last century. In 2003, the NCAA created the NCAA President Gerald R. Ford Award, which is presented annually to an individual who has provided significant leadership as an advocate for intercollegiate athletics on a continuous basis over the course of their career. In 2005, the Gerald R. Ford Legends of Center Award was created to honor and promote President Ford’s athletic and public service ideals. The award is presented annually to an outstanding former collegiate or professional football center who has also made significant contributions to his community through philanthropic or business endeavors.

32

CVN 78

“Long before he arrived in Washington, Gerald Ford’s word was good. During the three decades of public service that followed his arrival in our nation’s capital, time and again he would step forward and keep his promise even when the dark clouds of political crisis gathered over America. After a deluded gunman assassinated President Kennedy, our nation turned to Gerald Ford and a select handful of others to make sense of that madness. And the conspiracy theorists can say what they will, but the Warren Commission report will always have the final definitive say on this tragic matter. Why? Because Jerry Ford put his name on it and Jerry Ford’s word was always good. A decade later, when scandal forced a Vice President from office, President Nixon turned to the minority leader in the House to stabilize his administration because of Jerry Ford’s sterling reputation for integrity within the Congress. To political ally and adversary alike, Jerry Ford’s word was always good. And, of course, when the lie that was Watergate was finally laid bare, once again we entrusted our future and our hopes to this good man. The very sight of Chief Justice Burger administering the oath of office to our 38th President instantly restored the honor of the Oval Office and helped America begin to turn the page on one of our saddest chapters.” – President George H.W. Bush

P R ES I D EN T

“Jerry and I frequently agreed that one of the greatest blessings that we had after we left the White House during the last quarter-century was the intense personal friendship that bound us together … During our closely contested political campaign, as Don [Rumsfeld] just reminded me, we habitually referred to each other as ‘‘my distinguished opponent.’’ And, for my own benefit, while I was president, I kept him fully informed about everything that I did in the domestic or international arena. In fact, he was given a thorough briefing almost every month from the head of my White House staff or my National Security Adviser. And Jerry never came to the Washington area without being invited to have lunch with me at the White House. We always cherished those memories of now perhaps a long-lost bipartisan interrelationship … As president, I relished his sound advice. And he often, although, I must say, reluctantly, departed from the prevailing opinion of his political party to give me support on some of my most difficult challenges … We enjoyed each other’s private company. And he and I commented often that, when we were traveling somewhere in an automobile or airplane, we hated to reach our destination, because we enjoyed the private times that we had together. … One of my proudest moments was at the commemoration of the 200th birthday of the White House, when two noted historians both declared that the FordCarter friendship was the most intensely personal between any two presidents in history. …”

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

– President Jimmy Carter

WILLIS WARD The University of Michigan’s 1934 football season was not as strong as the previous two years. The Michigan Wolverines faced Georgia Tech in 1934, and Georgia Tech being from the South, and the year being 1934, Georgia Tech refused to take the field unless Michigan benched its star half-back Willis Ward. Why? Simply because Willis Ward was black. Unconscionable today, but the time was 1934, and Georgia Tech was set in its ways. Unfortunately, Michigan acquiesced and benched Ward. As the captain of the team, and close friend and roommate with Ward for away games, Ford was outraged. He decided to quit the team and stand up for his friend. Only after an emotional personal appeal from Willis Ward that he suit up and play for Ward and for the team did Ford take the field that Saturday. Michigan won the game (their only win that season!). The moral courage exhibited by team captain Ford that weekend was an early indicator as to how

G ER A L D

R.

F O R D

A game of basketball in the forward elevator well of USS Monterey (CVL 26) in 1944. The jumper on the left is future President Gerald R. Ford.

he would respond 40 years later when faced with an unprecedented challenge confronting the American people.

YALE LAW SCHOOL Mr. Ford chose the legal profession over a professional football career. To help pay for law school, he initially took a dual position as assistant varsity football coach and boxing coach at Yale University, where he coached future U.S. Senators Robert Taft, Jr., and William Proxmire. He enrolled in Yale Law School while also continuing his coaching responsibilities. Among an extraordinary group of law school classmates were future Supreme Court Justices Potter Stewart and Byron White, Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, Sargent Shriver, Pennsylvania Governors William Scranton and Raymond Shafer, U.S. Senator Peter Dominick, and author William Lord. Gerald Ford earned his LL.B. degree from Yale in 1941, and graduated in the top 25 percent of his class. After returning to Michigan and passing the bar exam, Mr. Ford and a University of Michigan fraternity brother, Philip A. Buchen (later to serve as President Ford’s White House Counsel), established a law partnership in Grand Rapids. Mr. Ford also became active in a local group of reform-minded Republicans who called themselves the Home Front. When the United States entered World War II. Mr. Ford promptly joined the U.S. Naval Reserve, where he received a commission as an ensign in April 1942 and subsequently was appointed lieutenant commander. Following an orientation program at Annapolis, he became an instructor at a pre-flight school in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. In spring 1943, he began service on the aircraft carrier USS Monterey. Initially assigned as a gunnery division officer, then assistant navigator, he took part in major operations in the South Pacific, including the battles for Truk, Saipan, Guam, Formosa, Marianas, and the Philippines. During a vicious typhoon in the Philippine Sea in USS GERALD R. FORD

33

STANDING READY TO SERVE AND PROTECT OUR NATION AND OUR FREEDOM.

T H A N K YO U, U S S G E R A L D R . F O R D ( C V N 7 8 ) .

Use of U.S. DoD visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

Photo courtesy of Huntington Ingalls Industries.

Congratulations and Best Wishes to the United States Navy on the Commissioning of the USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78). L3 is proud of our long-standing relationship with the nation’s shipbuilders and the U.S. Navy, and we are honored to provide our systems and expertise to this highly capable addition to the fleet. We wish the USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78) and its crew great success in the many years ahead. To learn more, please visit L3T.com/B2P.

Electronic Systems

L3T.com

P R ES I D EN T

“President Ford is remembered for the cheerful, unassuming spirit he brought to the nation’s highest office, at a time when a dose of the normal and the modest went a long way. Scandal, bitter conflict, needless drama and posturing – all of these were at their worst in Washington. And here, almost by chance, was perhaps the one man best suited to put it all behind us. Gerald Ford accomplished that by being more than a nice guy, though he surely was that. He saw America through its travails – through the end of the war in Vietnam as well – by wisdom and by strength of character. When Americans can look at the Oval Office and see our country’s finest qualities at work, that’s always worth a lot. In the 895 days of the Ford presidency, it mattered more than anything. No one who saw it up close can ever doubt the difference that one good man can make.”

G ER A L D

R.

F O R D

Gerald R. Ford, as an officer in the U.S. Navy in 1945.

– Vice President Dick Cheney

December 1944, he came within inches of being swept overboard. Severely damaged by the storm and a resulting fire, the ship had to be taken out of service. Lt. Cmdr. Ford was honorably released from active duty in February 1946, having been awarded an Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with one silver star and four bronze stars, a Philippine Liberation Ribbon with two bronze stars, an American Campaign Medal, and a World War II Victory Medal.

CONGRESS Following the war, his passion for public service remained. As one journalist emphasized, “(H)e came from a generation accustomed to difficult missions, shaped by the sacrifices and the deprivations of the Great Depression, a generation that gave up its innocence and youth to then win a great war and save the world. And when that generation came home from war, they were mature beyond their years and eager to make the world they had saved a better place. They re-enlisted as citizens and set out to serve their country in new ways, with political differences but always with the common goal of doing what’s best for the nation and all the people.” Returning home to Grand Rapids, Mr. Ford became a partner in the prestigious law firm of Butterfield, Keeney and Amberg. A self-proclaimed “compulsive joiner,” he was already well known throughout the community. He rejected his previous support for isolationism and USS GERALD R. FORD

35

P R ES I D EN T

G ER A L D

R.

F O R D

adopted, instead, an outlook more in keeping with America’s new-found responsibilities on the global stage. In 1948, with the encouragement of his hometown political hero, Sen. Arthur Vandenberg, and reinforced by his stepfather, who was county Republican chairman, Mr. Ford decided to challenge isolationist Congressman Bartel Jonkman in the Republican primary. Against all odds, the upstart Gerald Ford defeated Jonkman. In the subsequent general election that fall, he received 61 percent of the vote. At the age of 35, Gerald Ford was on his way to Washington for the first of 13 terms in the House of Representatives. A seat in Congress wasn’t the only thing he won in autumn 1948. On Oct. 15, at the height of the fall campaign, Mr. Ford married Elizabeth Ann Bloomer Warren. For more than 58 years, their partnership flourished, enriched immeasurably by their four children, Michael, John, Steven, and Susan, and by their grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Ford served in the House of Representatives from Jan. 3, 1949 to Dec. 6, 1973, being reelected 12 times, each time with more than 60 percent of the vote. The new Congressman quickly established a reputation for personal integrity, hard work, and the ability to deal effectively with both Republicans and Democrats – qualities that would define his entire political career. He once described himself as “a moderate in domestic affairs, an internationalist in foreign affairs, and a conservative in fiscal policy.” He became a member of the House Appropriations Committee in 1951 and rose to prominence on the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee, becoming its ranking minority member in 1961. In 1949, President Harry S. Truman invited him to the White House for a personal tour to examine the dilapidated and dangerous conditions of the White House. Mr. Ford subsequently was instrumental in securing necessary congressional funding to rebuild and modernize the White House during the Truman presidency. As his reputation as a legislator grew, Gerald Ford was called upon, among other assignments, to serve on the first NASA Oversight Committee and on the CIA and Intelligence Oversight Committees. He declined offers in the 1950s to run for both the Senate and the Michigan Governorship. His political ambition was specific – to become Speaker of the House. In 1960, he was mentioned as a possible vice presidential running mate for Richard Nixon. In 1963 a group of younger, more progressive House Republicans – the “Young Turks” – rebelled against their party’s leadership, and Mr. Ford defeated Charles Hoeven of Iowa for chairman of the House Republican Conference, the No. 3 leadership position in the party. In 1963, following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, President Lyndon Johnson appointed Gerald Ford to the Warren Commission that investigated the crime. Mr. Ford was the last living member of the Warren Commission. President George H.W. Bush assessed Ford’s central role on the Warren Commission: “The Warren Commission report will always have the final definitive say on this tragic matter. Why? Because Jerry Ford put his name on it and Jerry Ford’s word was always good.” The battle for the 1964 Republican presidential nomination was drawn on sharp ideological lines between Liberal Nelson Rockefeller and conservative Barry Goldwater. However, Mr. Ford

36

CVN 78

“Gerald Ford brought to the political arena no demons, no hidden agenda, no hit list or acts of vengeance. He knew who he was and he didn’t require consultants or gurus to change him. Moreover, the country knew who he was and despite occasional differences, large and small, it never lost its affection for the man from Michigan, the football player, the lawyer and the veteran, the Congressman and suburban husband, the champion of Main Street values who brought all of those qualities to the White House. Once there, he stayed true to form, never believing that he was suddenly wiser and infallible because he drank his morning coffee from a cup with a Presidential seal. He didn’t seek the office. And yet, as he told his friend, the late, great journalist Hugh Sidey, he was not frightened of the task before him. … My colleague Bob Schieffer called him the nicest man he ever met in politics. To that I would only add the most underestimated. In many ways I believe football was a metaphor for his life in politics and after. He played in the middle of the line. He was a center, a position that seldom receives much praise. But he had his hands on the ball for every play and no play could start without him. And when the game was over and others received the credit, he didn’t whine or whimper.” – Tom Brokaw

had previously endorsed Michigan’s favorite son, Gov. George Romney, and thus did not become embroiled in the resulting schism in the party. In the wake of Goldwater’s lopsided defeat at the hands of Johnson, Gerald Ford was chosen by the Young Turks to challenge Charles Halleck for the position of minority leader of the House. With the help of then- Congressmen Donald Rumsfeld and Bob Dole, Mr. Ford narrowly upset Halleck. He assumed his new position early in 1965 and held it for eight years. As minority leader, his national stature rose quickly. As part of his efforts to rebuild the Republican Party, he typically made more than 200 speeches a year across the country. Under Mr. Ford’s leadership, the House Republicans steadily gained members, but never a majority. In both the 1968 and 1972 elections, Mr. Ford was a supporter of Richard Nixon, who had been a friend for many years. In 1968, Gerald Ford was again mentioned as a possible vice presidential candidate. Not even the Nixon landslide of 1972 could give Republicans a majority in the House, thereby leaving Mr. Ford unable to reach his ultimate political goal – to be Speaker of the House of Representatives.

VICE PRESIDENT When Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned in October 1973, President Nixon was authorized by the 25th Amendment to appoint, subject to congressional confirmation, a replacement. He needed someone who could work with Congress, survive close scrutiny of his political career and private life, and be confirmed quickly. Heeding an immediate and strong bipartisan consensus, he chose Gerald R. Ford. Following one of the most thorough background investigations in the history of the FBI,

P R ES I D EN T

G ER A L D

R.

F O R D

President Gerald R. Ford is sworn in by Chief Justice Warren Burger.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Mr. Ford was confirmed by a vote of 92 to 3 in the Senate and 387 to 35 in the House of Representatives and sworn in as vice president on Dec. 6, 1973.

PRESIDENT The specter of the Watergate scandal, the break-in at Democratic headquarters during the 1972 campaign, and the ensuing coverup by Nixon administration officials hung over Mr. Ford’s ninemonth tenure as vice president. When it became apparent that evidence, public opinion, and the mood in Congress were all pointing toward impeachment, Richard Nixon became the only president to resign. On Aug. 9, 1974, Gerald Ford assumed the presidency amidst the gravest constitutional crisis since the Civil

War. Few presidents confronted so daunting a challenge. Not only did the new president face widespread public disillusionment in the wake of the Watergate scandals and the Vietnam War, he had to grapple with a devastating economic recession, a burgeoning energy crisis, and mounting tensions around the globe. The president who never sought the presidency resolved that his time in office, however long or short, would be a time of healing and energizing the country to move forward in a positive way. But it was President Ford’s confidence in his fellow citizens, and his devotion to our constitutional heritage, that helped him shoulder so effectively the burdens of the Oval Office. He immediately set about USS GERALD R. FORD

37

BEST WISHES

TO PRESIDENT FORD’S FAMILY AND ALL WHO SERVE ABOARD USS GERALD R. FORD (CVN 78).

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

P R ES I D EN T

restoring confidence in the presidency and healing the wounds of the nation. In his first speech as president – Lincolnesque in tone and Ford-like in its personal modesty – he said: “My fellow Americans, our long national nightmare is over. Our Constitution works; our great republic is a government of laws and not of men. Here the people rule. But there is a higher power, by whatever name we honor Him, who ordains not only righteousness but love, not only justice but mercy. As we bind up the internal wounds of Watergate, more painful and more poisonous than those of foreign wars, let us restore the golden rule to our political process, and let brotherly love purge our hearts of suspicion and of hate. With all the strength and all of the good sense I have gained from life … I now solemnly reaffirm my promise I made to you last December 6: to uphold the Constitution, to do what is right as God gives me to see the right, and to do the very best I can for America. God helping me, I will not let you down.”

G ER A L D

R.

F O R D

President Gerald R. Ford appearing at the House Judiciary Subcommittee hearing on pardoning former President Richard Nixon.

PARDON AND AMNESTY Shortly after becoming president, he announced amnesty terms for Vietnam-era draft evaders and pardoned his predecessor. Both acts were highly controversial at the time, but President Ford courageously put America’s best interests ahead of his own political popularity. The pardon of Richard Nixon was an act as personally courageous as it was politically detrimental. However, Mr. Ford strongly believed that protracted criminal proceedings would keep the country mired in Watergate and prevent the new administration and the American people from addressing other critical issues. Accordingly, he decided to grant the pardon prior to the filing of any formal criminal charges against the former president. Many in Washington and around the country were in an uproar, USS GERALD R. FORD

39

AT-6 WOLVERINE The Beechcraft AT-6 Wolverine provides the latest U.S. Air Force combat-proven technologies for armed reconnaissance and close air support, with HELLFIRE® precision and state-of-the-art sensor and weapons carriage versatility. Defeat threats with +6g maneuvering and battle-tested countermeasures while locating, targeting and engaging the enemy with the U.S. Air Force’s most trusted systems, including the A-10C mission system, MC-12W sensor and laser suite, and the accuracy of an F-16 CCIP targeting solution.

To learn more, contact: +1.316.676.0800 | Visit us at BeechcraftDefense.com.

©2015 Beechcraft Corporation. All rights reserved. Beechcraft is a registered trademark of the Beechcraft Corporation. HELLFIRE is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. All rights reserved. The sale and export of T-6/AT-6 series aircraft and associated technical data may require an export license under the ITAR (title 22, CFR, parts 120-130) or the EAR (title 15 CFR parts 730 to 774).

P R ES I D EN T

G ER A L D

R.

F O R D

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS PHOTO BY THOMAS J. HALLORAN

President Gerald R. Ford (center right) with Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin (center left) and others including Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (right) at the White House.

and Gerald Ford’s political honeymoon was over; his approval rating plummeted immediately with an estimated 60 percent of the American public disagreeing with the pardon. However, history has been much more generous regarding the pardon than were President Ford’s contemporaries. This historical reexamination of the pardon culminated in the May 2001 presentation of the Profile in Courage Award to President Ford by the John F. Kennedy Foundation. As Sen. Edward Kennedy explained in presenting the award: “At a time of national turmoil, America was fortunate that it was Gerald Ford who took the helm of the storm-tossed ship of state. Unlike many of us at the time, President Ford recognized that the nation had to move forward, and could not do so if there was a continuing effort to prosecute former President Nixon. So President Ford made a courageous decision – one that historians now say cost him his office – and he pardoned Richard Nixon. I was one of those who spoke out against his action then. But time has a way of clarifying past events, and now we see that President Ford was right. His courage and dedication to our country made it possible for us to begin the process of healing and put the tragedy of Watergate behind us.” President Ford’s Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, was equally direct in concluding that Gerald Ford “saved the country. In fact, he saved it in such a matter of fact way that he isn’t given credit for it.” Four decades later, the conclusion of historians across the spectrum is that President Ford’s decision to pardon Mr. Nixon was one of the most courageous acts in this history of the presidency.

NEW ADMINISTRATION Within the month, President Ford nominated Rockefeller for vice president. On Dec. 19, 1974, Congress confirmed Rockefeller, and the country once more had a full complement

of leaders. Mr. Ford confronted a divisive war in Southeast Asia, rising inflation at home, and a desperate need to restore the credibility of the presidency. He also found himself dealing with a Congress increasingly assertive of its rights and powers. The Ford philosophy was best summarized by one of his favorite speech lines: “A government big enough to give us everything we want is a government big enough to take from us everything we have.” In domestic policy, President Ford pioneered economic deregulation, formulated tax and spending cuts, and decontrolled energy prices to stimulate production. Through such steps, he successfully contained both inflation and unemployment, while at the same time reducing the size and role of a federal government whose growth to many observers seemed inexorable. Thus, President Ford foreshadowed subsequent efforts by his successors to continue these policies to make government smaller, smarter, and more supportive of private initiatives. He championed policies and legislation that brought about changes that today we take for granted, including individual retirement accounts (IRAs), automated teller machines (ATMs), Title IX regulations for women’s high school and college athletics, and the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act. The heavily Democratic Congress often disagreed with President Ford, which led to numerous confrontations and his frequent use of the veto to restrain runaway government spending. Presidential historian Richard Norton Smith described the essence of Gerald Ford’s leadership and strength of character: “President Ford never confused compromise with surrender, or moderation with weakness. While he had adversaries, he never had an enemy.” Columnist Mort Kondracke noted, “Gerald Ford represented the best in American politics … and [a style] that I’m afraid we are never going to see again.” Through tough negotiations and principled compromise and despite large Democratic majorities in Congress, landmark legislation was enacted to promote energy USS GERALD R. FORD

41

Your legacy of integrity comes to life today.

Below deck, on the bridge, or in the cockpit, you’ll find SKILCRAFT® products. We’re honored to help write a new chapter in our nation’s naval history.

SKILCRAFT® is a registered trademark of National Industries of the Blind, the nation’s largest employement resource for people who are blind.

An AbilityOne® authorized enterprise.

P R ES I D EN T

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS PHOTO BY MARION S. TRIKOSKO

decontrol, implement sweeping tax cuts, deregulate the railroad and securities industries, and reform antitrust laws.

OUTSTANDING CABINET AND WHITE HOUSE STAFF One of President Ford’s greatest strengths as a leader was his self-confidence and sense of security around others. According to columnist David Broder, President Ford “had one of the most competent staffs any of us have seen.” The advisers he appointed included a large number of extremely bright, capable people who would go on after the Ford administration to render further outstanding service to the American people. George H.W. Bush was his CIA Director; his White House chief of staff was Dick Cheney; his Secretary of State was Henry Kissinger; his chief economic advisor was Alan Greenspan; Donald Rumsfeld was his Secretary of Defense; his Attorney General was Edward Levi; his Secretary of Housing and Urban Development was Carla Hills; Brent Scowcroft was his National Security Advisor, William Simon was Treasury Secretary, and David Mathews was Secretary of HEW; his Under Secretary of Commerce was James Baker; his Secretary of Transportation was William Coleman; Frank Zarb was Administrator of the Federal Energy Administration; his OMB Director and Deputy Director were James Lynn and Paul O’Neill; and his White House staff included Robert Gates, James Cannon, John Marsh, Lawrence Eagleberger, Winston Lord, William Seidman, and Max Friedersdorf. And among his many appointees, none brought greater pride to President Ford than his appointment of John Paul Stevens to

G ER A L D

R.

F O R D

President Gerald R. Ford surrounded by members of the 94th Congress, including Majority Leader Tip O’Neill, after delivering the State of the Union address.

the United States Supreme Court. The list of President Ford’s outstanding advisers who continued with distinguished public service careers goes on and on.

FOREIGN POLICY In foreign policy, Mr. Ford was resolute and visionary. He continued the policy of détente with the Soviet Union and developed an aggressive “shuttle diplomacy” in the Middle East. U.S.Soviet relations were marked by ongoing arms negotiations, the Helsinki agreements on human rights principles and East European national boundaries, trade negotiations, and the symbolic Apollo-Soyuz joint manned space flight. One of President Ford’s boldest, and at the time most controversial, foreign policy initiatives occurred in southern Africa. For many years, U.S. policy was to support the government of South Africa, which for decades had practiced apartheid. In 1976, President Ford decided that a change in U.S. policy was long overdue, despite political considerations that strongly suggested otherwise. Secretary of State Kissinger went to Zambia and announced President Ford’s decision that the longstanding U.S. support of South Africa, with its unconscionable policies of apartheid, was over. Former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations William Scranton characterized this decision by President Ford as “one of the finest achievements” of twentieth century U.S. foreign policy. President Ford forcefully pushed for conclusion of the Helsinki agreements. His tireless efforts in negotiating those USS GERALD R. FORD

43

G ER A L D

R.

F O R D

“This president’s hardest decision was also among his first. And in September 1974, Gerald Ford was almost alone in understanding that there can be no healing without pardon. The consensus holds that this decision cost him an election. That is very likely so. The criticism was fierce. But President Ford had larger concerns at heart. And it is far from the worst fate that a man should be remembered for his capacity to forgive. In politics it can take a generation or more for a matter to settle, for tempers to cool. The distance of time has clarified many things about President Gerald Ford. And now death has done its part to reveal this man and the president for what he was. He was not just a cheerful and pleasant man – although these virtues are rare enough at the commanding heights. He was not just a nice guy, the next-door neighbor whose luck landed him in the White House. It was this man, Gerald R. Ford, who led our republic safely through a crisis that could have turned to catastrophe. We will never know what further unravelings, what greater malevolence might have come in that time of furies turned loose and hearts turned cold. But we do know this: America was spared the worst. And this was the doing of an American president.” – Vice President Dick Cheney

44

CVN 78

President Gerald R. Ford meeting with Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld at the White House.

agreements, though politically controversial at the time, are now seen with the benefit of history as the first step toward democratization of Eastern Europe and the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union. Years later Colin Powell declared Gerald Ford’s leadership and personal participation in the Helsinki agreements as “a bold, brave, visionary act” and “one of President Ford’s greatest moments.” “Historians will debate for a long time over which president contributed most to victory in the Cold War,” said Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in summarizing President Ford’s profound impact. “Few will dispute that the Cold War could not have been won had not Gerald Ford emerged at a tragic period to restore equilibrium to America and confidence in its international role.” President Ford’s personal diplomacy also included trips to Japan – the first by an American president – and China; a 10-day European tour; and establishment of the annual international economic meeting of leaders (today known as the G-8 summits). In addition, as America’s Bicentennial president, Gerald Ford received numerous foreign heads of state in the nation’s capital. Henry Kissinger noted the depth and breadth of President Ford’s achievements in foreign policy. “President Ford established the

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS PHOTO BY MARION S. TRIKOSKO

P R ES I D EN T

P R ES I D EN T

closest relationship of any American President, in any period, with European leaders, and he did this by his special qualities – openness, intelligence, directness,” Kissinger said. “And what is even more remarkable is that they have remained friends of his even after he left government … Abroad, his reputation was enormous.” With the fall of South Vietnam in 1975 as background, Congress and President Ford repeatedly clashed over presidential powers, oversight of the CIA and covert operations, military aid appropriations, and the stationing of military personnel. On May 14, 1975, just days after Saigon fell, President Ford ordered U.S. forces to retake the SS Mayaguez, an American merchant ship seized by Cambodian gunboats in international waters two days earlier. The vessel was recovered, and all 39 crewmembers were saved. Unfortunately, 41 brave Americans lost their lives in the preparation and execution of the rescue. The president himself did not escape the tumult of those times. On two separate trips to California in September 1975, Gerald Ford was the target of assassination attempts. The next year he fought off a strong challenge from Ronald Reagan to secure the Republican nomination for president, and a chance to have his leadership confirmed by the voters. He chose Sen. Robert Dole of Kansas as his running mate. The Ford-Dole team succeeded in narrowing Democrat Jimmy Carter’s large lead in the polls, only to fall short in one of the closest presidential elections in U.S. history.

THE PRESIDENCY OF GERALD FORD The presidency of Gerald Ford is defined by his personal integrity and unbending adherence to the truth. Ever the Eagle Scout – literally and metaphorically – in reflecting on his life, President Ford consistently referred to the straightforward standards of conduct taught by his parents: “Work hard, tell the truth, and come to dinner on time.” Openness was, and is, a core Ford family value. He brought to the political arena “no demons, no hidden agenda, no hit list or acts of vengeance. He knew who he was and he didn’t require consultants or gurus to change him.” Equally honest and open was Betty Ford, who as First Lady developed a reputation for candor and lack of pretense. President Ford strongly supported his wife in her battles with breast cancer, alcoholism, and addiction to prescription medicines, and he warmly endorsed her frank talk about these and other issues. In 2003 Vice President Dick Cheney observed, “President Ford restored trust and confidence in the presidency and the White House simply by the sheer force of his character.” Thus, by the time of the nation’s Bicentennial, the American people had a renewed pride in their free institutions, and in themselves. Presidential biographer Richard Reeves acknowledged that his earlier assessment of the 38th President had been unduly harsh. A quarter century later, Reeves took a very different tack: “We judge presidents by the one or two big things that they do,” he wrote. “Nobody remembers that Lincoln balanced the budget, and nobody cares. In the end, President Ford did the indispensable thing he had to do, which was hold the country together.” With the passage of time and the perspective

G ER A L D

R.

F O R D

of a broader historical context, the presidency of Gerald Ford has been understood and acknowledged with much greater clarity and appreciation. Columnist David Broder was unequivocal: “In an odd, inexplicable way, the truth has begun to dawn on people – that he was the kind of president Americans wanted – and didn’t know they had.” Former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill concluded, “God has been good to America, especially during difficult times. At the time of the Civil War, he gave us Abraham Lincoln. And at the time of Watergate, he gave us Gerald Ford – the right man at the right time who was able to put the nation back together.” Former Sen. Tom Daschle observed, “As our president, Gerald Ford did more than wake us from our long national nightmare; he made it possible for us to dream again.” As President Jimmy Carter graciously acknowledged on Jan. 20, 1977, with his first words as president, the man from Grand Rapids had indeed healed the land.

PRIVATE CITIZEN Upon returning to private life, President and Mrs. Ford moved to California, where they built a home in Rancho Mirage. President Ford’s memoir A Time to Heal was published in 1979. He remained an active participant in the political process. He spoke out on important political issues and wrote numerous op-ed columns and other articles dealing with issues ranging from support for stem cell research and affirmative action, to urging a censure alternative to the impeachment of President Bill Clinton. In 1999, 25 years after he assumed the presidency, he returned to the East Room of the White House to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He and Mrs. Ford were also awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, the first-ever joint presentation of Congress’ highest civilian honor. In November 2006, President Ford became the longest-living president in U.S. history. The year 1981 saw the dedication of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Both institutions quickly established themselves as an important part of the Ford legacy. In 2006, the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy moved into its new home at the University of Michigan. President Ford was a frequent participant in conferences examining Congress, the presidency, and foreign policy; Soviet-American relations; German reunification, the Atlantic Alliance, the future of American foreign policy; national security requirements for the 1990s; humor and the presidency; and the role of first ladies in the life of the nation. At hundreds of colleges and universities, he lectured on Congressional/White House relations, federal budget policies, and domestic and foreign policy issues. He attended the annual Public Policy Week Conferences of the American Enterprise Institute, and in 1982 established the AEI World Forum, which he hosted for many years in Vail, Colorado. This continues as an international gathering of former and current world leaders, as well as business executives – all gathered to discuss issues of topical concern. On Aug. 9, 2004, President Ford spoke in Statuary Hall at the USS GERALD R. FORD

45

Congratulations On the commissioning of the USS Gerald R. Ford

“

”

We salute our U.S. military and are proud supporters of the first-in-class addition to our Navy fleet—the CVN-78

U.S. Navy photo by Joshua J. Wahl

The American Iron and Steel Institute and the people who work in the American steel industry

P R ES I D EN T

G ER A L D

R.

F O R D

President Gerald R. Ford U.S. Capitol to members of his cabinet with his daughter, Susan and White House staff and reflected on Ford Bales. his life and presidency. “At my stage in life, one is inclined to think less about dates on a calendar than those things that are timeless – about leadership and service and patriotism and sacrifice, about doing one’s best in meeting every challenge that life presents,” he said. “History will judge our success. But no one can doubt our dedication. We set out to bind America’s wounds, and to heal America’s heart. By the time we celebrated our Bicentennial in 1976, we celebrated more than a distant event – we were able to take heart ourselves from the renewal of the great truths expressed by our Founders. Without seeking them, I was called upon to fill this nation’s highest offices. For two and a half years, I had the greatest privilege that can come to any American – to lead my countrymen through trying times, and uphold the sacred honor of free men and women everywhere. So I ask you to join me in saluting the past, savoring the present, and anticipating the future. For in America, the best has never been – it is always yet to be.”

FAREWELL President Ford died on Dec. 26, 2006, at his California home. During the several days of state funeral services and tributes in California, Washington, DC, and Michigan, tens of thousands of Americans turned out to express their gratitude and pay tribute to President Ford. The services and tributes were a symbolic mosaic to President Ford, the leader, and Gerald Ford, the man. The state funeral, and its thematic mosaic, let Americans young and old consider him in a broader historical context. Author Peggy Noonan later wrote,“[President] Ford’s was the most human of presidential funerals. Maybe because the Fords wanted so little done, so insisted on modesty, all that was done was genuine, and sincere, and – perfect.” The tributes to President Ford continued after his death. On Jan. 16, 2007, Navy Secretary Donald Winter named America’s next aircraft carrier, CVN 78, the USS Gerald R. Ford. And in 2011, a magnificent new statue of President Ford was placed in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda. Historian Jon Meacham reflected on Gerald Ford’s place in the broad sweep of history. “President Ford was a man who trusted in the essential goodness of the people and who knew the dangers of excessive faction and extremism,” Meacham said. “No other American president, including Washington himself, has more closely resembled the ideal of the Roman leader Cincinnatus – the man who was summoned from his plow against his will to restore faith in the republican ideal. Like Cincinnatus, Gerald Ford did not seek – but did accept – ultimate responsibility in an hour of maximum danger. We live in a better and brighter country because he answered that call.” Vice President Dick Cheney concurred. “It was Gerald R. Ford who led our republic safely through a crisis that could have turned to catastrophe,” Cheney said. “We will never know what further

unravelings, what greater malevolence might have come in that time of furies turned loose and hearts turned cold. But we do know this: America was spared the worst. And this was the doing of one man – an extraordinary man and American president. For all the grief that never came, for all the wounds that were never inflicted, the people of the United States will forever stand in debt to that good man and faithful servant from Michigan – Gerald R. Ford.” USS GERALD R. FORD

47

I N T ER V I E W

Susan Ford Bales SHIP’S SPONSOR SUSAN FORD BALES IS A VIRGINIA NATIVE and now resides in Tulsa, Oklahoma. She is the daughter of President Gerald R. Ford and Betty Ford and is married to Vaden Bales, an attorney with the Hall Estill firm in Tulsa. Susan is the mother of two daughters, Tyne Berlanga and Heather Devers, three grandchildren, Joy Elizabeth Berlanga, Cruz Vance Berlanga, Elizabeth Blanche Devers, and three step-sons, Kevin, Matthew, and Andrew Bales. Susan was raised in Alexandria, Virginia, and attended Holton Arms School and the University of Kansas, where she studied photojournalism. She is the recipient of an honorary doctorate of public service degree, an honorary doctorate of letters degree, and an honorary doctorate of humane letters degree. She is the author of two novels set in the White House, Double Exposure: A First Daughter Mystery, and its sequel, Sharp Focus. Susan is the Ship’s Sponsor for the aircraft carrier USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78), which she officially christened on Nov. 9, 2013. On April 8, 2016, in recognition of her extraordinary service as the Ship’s Sponsor, she was named an honorary naval aviator by the United States Navy, becoming only the 31st American to receive this distinction. And history was made with her selection – Susan is the first woman to be chosen as an honorary naval aviator. Susan has served as a trustee of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Foundation since 1981 and currently serves as

co-chair of the Foundation’s Programs Committee. Susan’s work with the foundation centers on promoting the ideals of integrity, courage, and candor that were the hallmarks of America’s 38th president and his distinguished service as a naval officer in World War II, member of Congress, and as vice president and president. During her high school years, Susan lived in the White House and served as official White House hostess following her mother’s surgery for breast cancer in 1974. In 1984, she and her mother helped launch National Breast Cancer Awareness Month, and Susan subsequently served as national spokesperson for breast cancer awareness. Since the founding of the Betty Ford Center in 1982, Susan worked side by side with her mother on projects at the center and was elected to the center’s board of directors in 1992. She succeeded her mother as chairman of the board from 2005-2010, and currently serves on the board of directors of the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation. In addition to her many charitable and public service activities, Susan serves as co-trustee of the President Gerald R. Ford Historical Legacy Trust, a member of the advisory board of the Rosalynn Carter Fellowships for Mental Health, trustee of the Elizabeth B. Ford Charitable Trust, global ambassador for Susan G. Komen for the Cure, the executive board of the Betty Ford Alpine Gardens Foundation, and the Honorary Advisory Committee of the Children’s National Medical Center.

How did your father feel knowing this new aircraft carrier and carrier class were being named for him? Susan Ford Bales: From the moment he learned that CVN 78 was going to be named for him, Dad was, as they say, on Cloud 9! He displayed so many emotions – surprised, amazed, humbled, proud, grateful, happy – and then some! Most of all was his gratitude for such an honor. He tried and tried, but, not surprisingly, was never able to find the words that he felt adequately expressed how much the naming of the new aircraft carrier and carrier class meant to him. It was so funny to watch the almost boyish excitement and enthusiasm anytime the subject of CVN 78 came up. Whenever Mom and I would mention CVN 78 to Dad, we knew we would immediately see Dad’s great big grin and hear a steady stream of comments about the ship. There were particular moments the last year of his life that are vivid memories when I think about Dad’s feelings about

the ship. In late summer of 2006, he learned about the naming for the first time. Vice President [Dick] Cheney telephoned him to share the news of Navy Secretary [Donald] Winter’s intentions for the name of CVN 78. Several weeks later, Secretary Winter held a meeting at the Pentagon to plan the official Naming Ceremony, and right after the meeting Dad, Mom, and I received a telephone report about the ship and its naming plans. And then, during Thanksgiving, Defense Secretary Don Rumsfeld and Joyce [Rumsfeld] made a surprise visit to see Dad and gave him a USS Gerald R. Ford ball cap. Every one of those moments is a special memory. And even though Dad’s health was fading, he was ebullient with every one of those moments and would chatter for days afterwards about those conversations and his soon-to-be namesake aircraft carrier. I’ve tried for years to describe what this honor meant to Dad; I always come up short. As was so often the case with

48

CVN 78

I N T ER V I E W

Dad, his own words about the ship are the best guide. That’s why it’s so fitting that the words from his letter about CVN 78 are now a permanent part of the ship’s statue of Dad as lieutenant commander in World War II. Your father served as a naval officer in World War II aboard the aircraft carrier USS Monterey (CVL 26). Did he talk often about his naval service and what it meant to him? Almost never; in fact, I can probably count on less than one hand the number of times he talked to me about his service as a naval officer in World War II. His attitude was like so many of his generation. He saw it as his duty to serve his country, and, after Pearl Harbor, he volunteered to do so – no fanfare, no self-aggrandizement, no bravado. He and his comrades proudly did their duty – end of story. One of the eulogists at Dad’s state funeral captured that part of Dad’s life well: …(H)e came from a generation accustomed to difficult missions, shaped by the sacrifices and the deprivations of the Great Depression, a generation that gave up its innocence and youth to then win a great war and save the world. And when that generation came home from war, they were mature beyond their years and eager to make the world they had saved a better place. They re-enlisted as citizens and set out to serve their country in new ways, with political differences but always with the common goal of doing what’s best for the nation and all the people. When he entered the Oval Office, by fate not by design, Citizen Ford knew that he was not perfect, just as he knew he was not perfect when he left. But he was prepared because he had served his country every day of his adult life, and he left the Oval Office a much better place.

Caption needed

Do you think his service, especially in combat, affected his decision-making when he became Commander in Chief? Without question, Dad’s service in World War II directly affected his perspectives as Commander in Chief. Like a number of our presidents, he saw first-hand the ravages of war and the horrors of combat. How can that experience not affect you when contemplating sending our brave men and women in uniform into harm’s way? And, if the history books teach us nothing else, they vividly illustrate how military service affected those presidents who wore the uniform. I suspect Dad’s perspectives as Commander in Chief were strikingly similar to those formed by others who served, such as Washington, Jackson, Lincoln, Teddy Roosevelt, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Bush, and others. There is USS GERALD R. FORD

49

I N T ER V I E W

U.S. NAVY PHOTO BY PETTY OFFICER 3RD CLASS SEAN ELLIOTT

Capt. Richard C. McCormack, commanding officer, PreCommissioning Unit Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78), and Susan Ford Bales, Ship’s Sponsor, tour a jet shell located on elevator one in Ford’s hangar bay during a guided visit aboard the ship. Bales is the daughter of the ship’s namesake, President Gerald R. Ford.

nothing – absolutely nothing – more difficult for a president – and Dad certainly felt that way! – than issuing orders that put at risk the lives of Americans in uniform. Dad bore that solemn responsibility to the depths of his soul. Tell us about how it was that you became the Ship’s Sponsor of your father’s namesake aircraft carrier. Oh, if only there was some great narrative behind it all. It wasn’t because I harbored a mountain of Ship’s Sponsor expertise that made me the odds-on favorite – that’s for sure! Seriously, the selection of a sponsor is steeped in Navy

tradition. And I had an advantage on my brothers – the tradition is that sponsors are females. That 2006 telephone call Dad, Mom, and I had about Secretary Winter’s planning meeting at the Pentagon was the first time I learned I was being considered as the CVN 78 Ship’s Sponsor. Initially, I thought Mom should be selected. I talked about it with Mom and Dad. They felt strongly that I should do it. They wanted to be sure that the Ship’s Sponsor could carry out their wishes for the ship for several decades. So, I proudly accepted Secretary Winter’s designation, and almost 11 years later the honor and joy I’ve experienced is USS GERALD R. FORD

51

Congratulations to the Captain and Crew! May God Bless You All and Keep You All Safe.

Congratulations Susan Ford Bales on such an impressive ship. Your dedication and hard work are a lasting tribute to the USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78).

Mary and MaryPat Woodard

I N T ER V I E W

U.S. NAVY PHOTO BY MASS COMMUNICATION SPECIALIST SEAMAN APPRENTICE GITTE SCHIRRMACHER

beyond description. I could not be prouder or more grateful to serve in this role. What are the duties of the Ship’s Sponsor? Is there a manual that tells you what’s expected? I originally hoped there was a book somewhere titled: Seven Easy Steps To Being A Ship’s Sponsor. Alas, there’s no CliffNotes ®, or how-to instructions, for a Ship’s Sponsor. Other than breaking the bottle of sparkling water on the ship’s bow at the christening, and when I “bring the ship to life” at the commissioning, there are no specified duties for a Sponsor. But, in a way, that’s a real benefit. Each of us can shape our role to fit our own priorities and those of our ship. And, in my case, I could focus on carrying out what Dad would have set as his priorities with the ship. It’s been fantastic, and I know Dad would share my happiness. As the Ship’s Sponsor of this first-in-class aircraft carrier, what have been your priorities? My priorities have evolved since 2006. In the early years, my focus was 100 percent on the shipbuilders. I visited

Ship’s Sponsor Susan Ford Bales poses with the PreCommissioning Unit Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78) choir during a reception following a change of command in the ship’s hangar bay. Ford is the first of a new class of aircraft carriers.

the ship as often as I could. My mantra at the shipyard was always the same – tell me how I can help! And, my goodness, did the shipbuilders ever take up my challenge; they put me to work, and I loved it! Then, when the first commanding officer, John Meier, and the first crew members began to arrive, I expanded my priorities to focus also on the crewmembers and, in particular, their families. First and foremost, I want to make certain to always tell the shipbuilders and crewmembers how much I appreciate their sacrifice and service to our country. Secondly, I want to convey to them how much this ship meant to Dad and his own “Integrity at the Helm.” CVN 78 and those who built her and will serve aboard her are the most magnificent tribute Dad will ever receive. In a very personal sense, the shipbuilders and crew embody Dad’s legacy in an unprecedented way. And, finally, I want to make certain that all of us involved with the ship set a standard of integrity and USS GERALD R. FORD

53

I N T ER V I E W

excellence that will define CVN 78 and each of the ships in the Ford class. If my service as Ship’s Sponsor has helped the shipbuilders and crew in their responsibilities, if I’ve made them proud to be associated with this ship and Dad’s legacy of integrity, or if their families have an extra gleam of happiness from activities we’ve done together, then mark me down as the proudest Ship’s Sponsor in the history of the United States Navy. During his visit to CVN 78 earlier this year, President Donald Trump was clearly quite impressed by your tireless support to the shipbuilders and the crew, and he specifically explained to the thousands gathered in the hangar bay that you had made 17 visits to the ship. Tell us about those trips and what you’ve learned about the shipbuilders and sailors. Unless there is some ceremonial activity I need to do, when I visit the ship I want to do two things: spend time with the shipbuilders and crew, especially to tell them how grateful I am – and Dad most certainly would be – and do any task – no matter how large or small – I can to make their lives on board a little nicer and satisfying. On my many visits, I’ve pulled cables, punched holes, welded, served food to the sailors in the mess, installed telephone systems, worked on the dual-band radar, calibrated laser measurements, tested the anchors and weapons elevators, participated in All Hands Calls, worked up in the giant big blue crane, and assisted with signal commands out on the flight deck to test the EMALS by launching sleds into the James River. And, of course, we’ve had lots of fun and laughs along the way. One of the great moments was when Matt Mulherin, president of Newport News Shipbuilding, announced that they’d designated me as an honorary shipbuilder. It is fantastic to be able to say: “my fellow Newport News Shipbuilders.” What I’ve learned along the way is that the shipbuilders and crewmembers come from all walks of life in America; it is such an amazing tapestry. Common to every single one of them – without exception – is a love of country and a personal character of integrity and courage without equal. Dad summed it up perfectly when he wrote that there’s no greater honor he ever received than to have his name and our family’s name associated with the brave men and women of the USS Gerald R. Ford. Your father, like any political leader, had many political adversaries, but it’s virtually impossible to find anyone who didn’t like and respect him as a person. Why was that the case, especially considering the political adversaries who (remarkably) were close personal friends of his? There are lots of reasons people point to, but I think they all have a common denominator – he was a great listener. It didn’t matter if you were some powerful political leader, corporate luminary, or a classmate from South High in Grand Rapids [Michigan]. Dad always listened to what you had to say and did so with a genuineness and interest that inevitably made disagreements less disagreeable – much less disagreeable.

You have spent hundreds and hundreds of hours with the shipbuilders and the crew. What are some of your favorite memories of those interactions? That’s easy; the countless friendships I’ve made with shipbuilders and crewmembers. They are such wonderful people, and I’m blessed to call them my friends. They will forever have a special place in my heart. Last year, I was completely surprised when it was announced at the change-of-command ceremony that Adm. John Richardson, Chief of Naval Operations, had appointed me as the first female honorary naval aviator in history. To be sure, the appointment itself was special and extraordinary. But it was made even more meaningful when I learned from Adm. Richardson and from dozens of comments made to me afterwards that the decision was intended to specifically recognize the positive impacts I’ve had on the lives of the CVN 78 crewmembers and their families. Without question, I’ll cherish that memory and my wings of gold forever. What has impressed you the most about the aircraft carrier itself? No matter how many times I’ve been to the ship, I’m simply gobsmacked on every visit by how absolutely massive she is. People sometimes refer to her as a “floating city.” I used to think that was silly. I don’t anymore; it’s the best description there is. As Commanding Officer Rick McCormack and I have observed many times, she is indeed the mightiest ship ever built. USS Gerald R. Ford will sail for many decades, and tens of thousands of sailors will live and serve aboard this ship. What about your father would you want them to keep in mind as they serve aboard her? Dad showed America and the world, by word and deed, that doing the “right” thing is not always easy, and it’s definitely not always popular. At the end of Dad’s life’s journey, the integrity to do the “right” thing is the example he left for all of us, most especially for the crew of his namesake carrier. I hope the crews who serve aboard CVN 78 will follow his example every day and do the “right” thing, no matter the challenges or difficulties that “thing” may pose. What a wonderful testament to Dad that would be! Your father’s personal integrity is the cornerstone of the ship’s motto – Integrity at the Helm. What do you remember most about his integrity as a dad? Whether he was called lieutenant commander, Congressman, Mr. President, Jerry, or Dad, he was always the same wonderful man. There were no hidden agendas, no lurking demons, and no bursts of bravado. The person whose Integrity At The Helm the public witnessed for decades is the same special person who was at our home. How lucky I was that he was my dad. I know he’ll be watching over me every step of commissioning week. I miss him. USS GERALD R. FORD

55

Congratulations to the Captain and Crew on the Commissioning of USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78) into the United States Navy Steve & Amy Van Andel

C O