11 minute read

VA Research

Approaching a century of lighting the way

By Craig Collins

In September of 2021, a team of VA researchers added to the medical community’s growing understanding of a novel coronavirus which, just two years earlier, almost nobody knew existed. The study, reported in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, compared data from almost 90,000 people who’d recovered from the virus known as SARS-CoV-2 to data from a control group of more than 1.6 million people who had not had the virus. Among its findings was that those who had the viral disease now known as COVID-19 – even a mild or moderate case – had three times the risk of end-stage kidney disease, requiring dialysis or a kidney transplant, than the uninfected.

Led by Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research and development at the VA St. Louis Health Care System, the study was one of many launched within the previous year-and-a-half – some of them, like Al-Aly’s kidney study, deep dives into medical record data in search of insights about risk factors, disease pathways, and outcomes for COVID-19 patients; some of them clinical trials exploring vaccines or therapies for the disease; and some of them observational studies to better understand its clinical course. All of these studies, of course, were launched – and several completed – within the first 18 months of a global pandemic that severely limited the ability of professionals to work together and learn how to combat a new and bewildering disease.

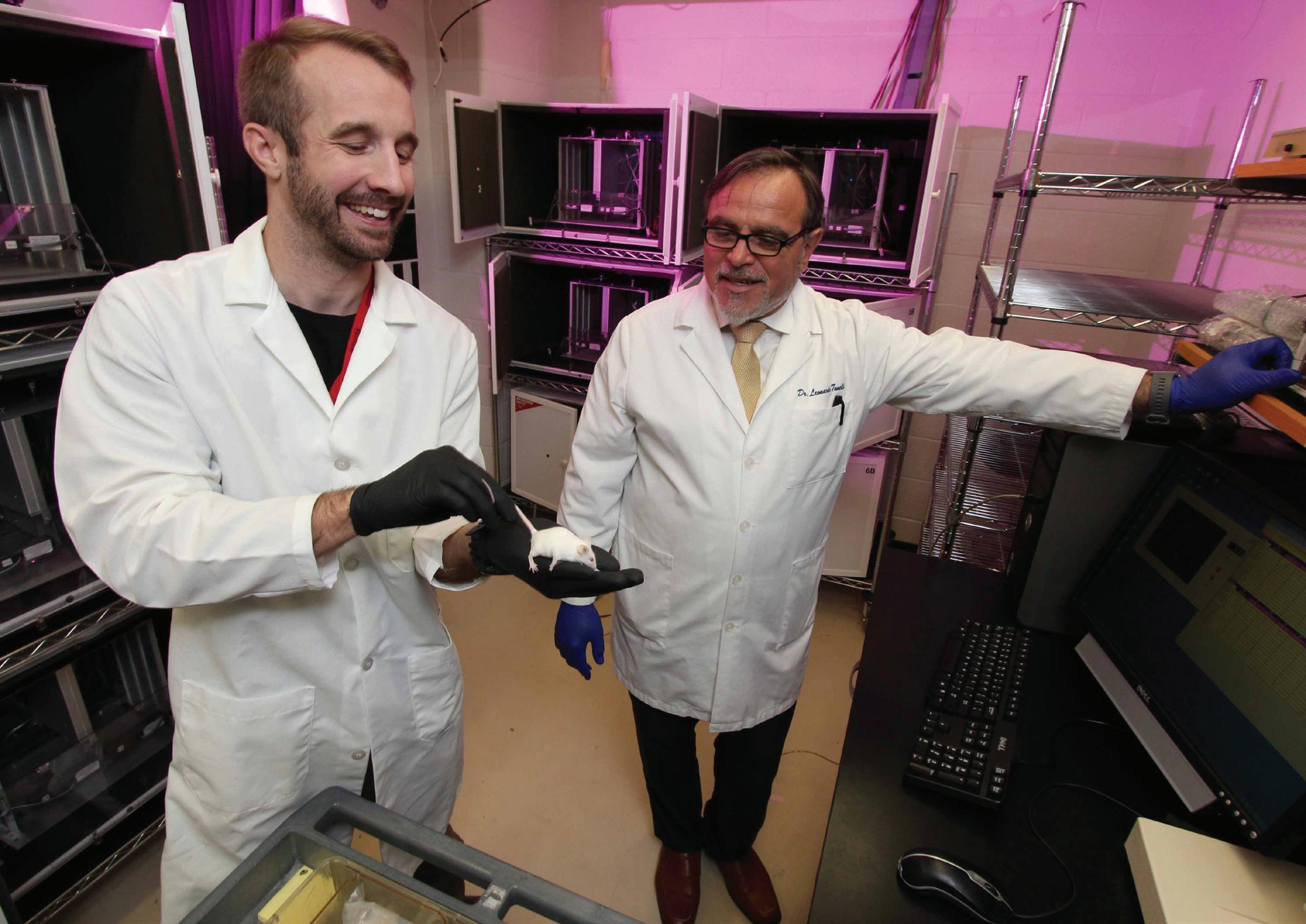

Leonardo Tonelli, PhD, (right) and research assistant Brent Stewart are conducting mouse studies to learn about the role of the immune system in mental health.

How such a research program came to exist, is capable of rapidly mobilizing the nation’s foremost clinical experts against a deadly disease, and learns from hundreds of thousands of volunteer participants, is a story that reaches deeper into American history than most people realize. Now nearly a century old – older than the National Institutes of Health – the research program of the Veterans Health Administration, now housed within the Office of Research and Development (ORD), funds more than 2,250 total projects, partners with more than 200 medical schools and other institutions, and supports the work of more than 3,600 investigators who are funded directly by ORD or by outside sources. Principal investigators are often VA clinicians on the leading edge of medical knowledge. Over more than nine decades, the program has pioneered therapies and technologies that have contributed to the well-being of the nation’s Veterans and people around the world.

William Unger, PhD, a PTSD clinician and researcher at the Providence VA Medical Center, has studied the use of virtual reality in PTSD treatment.

ORIGINS

It was after World War I when the nation’s concept of a hospital began to change. Long considered charitable institutions designed to serve the poor, the hospitals of the U.S. Public Health Service became, with the 1921 creation of the Veterans Bureau, anchors of a federally funded health care system for Veterans of World War I. In 1924, Congress extended federal hospitalization benefits to Veterans of every war, regardless of disability, and within a year the bureau was caring for 30,000 hospitalized Veterans.

A 22-member Council on Medical Affairs, established to offer the bureau advice, quickly recognized that knowledge gleaned from such a large patient population could be of great benefit in advancing medical science and the delivery of health care to Veterans. The council recommended a system of diagnostic hospital beds, the establishment of a research program emphasizing investigations related to Veterans’ health care needs, and the publication of the bureau’s research findings in a journal.

The Veterans Health Administration did not solicit or approve this content

Articles published in the United States Veterans Bureau Medical Bulletin, issued continuously from 1925 until 1944, depicted a hospital-based research program aimed at curing diseases through systematic observations, with an emphasis on outcomes. Under the leadership of the bureau’s first Research Chief, Dr. Philip B. Matz, MD, physicians published articles on topics such as malaria, cancer, tuberculosis, the long-term effects of chemical warfare, cardiovascular health, and morbidity and mortality among Veterans with mental illness. This early work produced several influential studies that were later published in the nation’s most prestigious medical journals. It also contributed to observable outcomes: Tuberculosis, the predominant condition treated at early Veterans’ hospitals, accounted for only about 13 percent of the conditions treated by the middle of the 1930s.

During its first several years, the bureau’s research was conducted without direct federal funding – a circumstance removed in 1930, when the bureau was expanded, renamed the Veterans Administration, and established its own research laboratories. The first VA-funded laboratory, the Tumor Research Unit at Hines Hospital in Chicago, received funding in 1933. It was here that Dr. Robert Schrek, MD, one of the first researchers to study the effects of radiation on cancer cells, discovered the link between sun exposure and skin cancer. Two additional VA laboratories were established in 1935: the Neuropsychiatric Research Unit in Northport, New York, and the Cardiovascular Research Unit in Washington, D.C. The Cardiovascular Research Unit would later publish a study in the New England Journal of Medicine that demonstrated a link between cardiovascular disease and hypertension among World War II Veterans.

VA RESEARCH IN THE POSTWAR ERA

Veteran research, along with many other government functions, entered a dormant period as doctors entered service in World War II. At war’s end, the VA employed about 2,300 doctors, nearly three-quarters of whom were still on active military duty.

VA would emerge from World War II with an expanded structure and purpose, courtesy of Public Law 79-293. In January of 1946, the law established the Department of Medicine and Surgery (forerunner to the modern Veterans Health Administration), and authorized the agency to directly hire its own doctors, dentists, nurses, administrators, and other professionals. The law also provided the legal basis for affiliations between the VA and American medical schools, which had provided valuable expertise and insight to military medicine during the war.

The new VA offered good pay, a large patient cohort treated in state-of-the-art facilities, and the opportunity to serve one’s country alongside colleagues from some of the nation’s best medical schools. Within six months of the law’s passage, VA’s full-time physicians had increased from 600 to 4,000.

The Veterans Health Administration did not solicit or approve this content

As dedicated VA staff physicians began leading clinical studies of Veterans’ health issues, the findings inevitably carried implications for the general population. In every decade after World War II, the VA research program employed world-class investigators whose groundbreaking discoveries are now everyday knowledge for health care professionals: biological substances such as hormones, vitamins, and enzymes. Their discovery is today considered one of the most important in the field of endocrinology. on anti-rejection medications that increased transplant survival rates.

TRAILBLAZING VA RESEARCHERS

Oscar Auerbach, MD

Oscar Auerbach, MD, a pathologist who began his VA career in 1947, built on Schrek’s tumor research and became the first physician to link smoking to lung cancer – and later, to heart damage.

VA PHOTO

Rosalyn Yalow, PhD

At the Bronx VA Hospital, beginning in 1947, Bernard Roswit, MD, and Rosalyn Yalow, PhD, investigated health issues related to Veterans who’d been sickened by radiation exposure during nuclear weapons testing in the Pacific. Yalow would later collaborate with Solomon Berson, MD, at the Bronx VA to develop radioimmunoassay, a technique that traces radioisotopes in the blood to allow measurement of biological substances such as hormones, vitamins, and enzymes. Their discovery is today considered one of the most important in the field of endocrinology.

VA PHOTO

William Oldendorf, MD

William Oldendorf, MD, of the West Los Angeles VA Medical Center (now part of the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System), invented the idea of a computerized tomography (CT) scanner, which assembles multiple X-ray images of structures into cross-sectional images, or “slices,” of the body, during the 1950s. VA researchers eventually turned Oldendorf’s idea into a working CT scanner.

VA PHOTO

The idea of the CT scanner was originated by William Oldendorf, MD.

VA PHOTO

Thomas Starzl, MD

Thomas Starzl, MD, a transplant surgeon and research scientist for more than 50 years at VA medical centers in Chicago, Denver, and Pittsburgh, was widely regarded as the “father of transplantation,” with research that not only focused on surgical transplants – he performed the first successful liver transplant in 1967 – but also pioneered work on anti-rejection medications that increased transplant survival rates.

VA Photo

Michael DeBakey, MD

Michael DeBakey, MD, often called the “father of modern cardiovascular surgery,” performed many firsts throughout his illustrious career: He pioneered dozens of procedures including aneurysm repair, coronary bypass, and endarterectomy, which save thousands of lives each year. He also performed some of the first heart transplants, and supervised the first multi-organ transplant in 1968. For 55 years, DeBakey chaired the dean’s committee at the Houston VA Medical Center that now bears his name.

VA PHOTO

Andrew Schally, PhD

Endocrinologist Andrew Schally, PhD, directed hypothalamus research at the New Orleans and Miami VA Medical Centers and developed the knowledge of how the brain controls body chemistry through the release of peptide hormones. A full-time VA researcher since 1962, Schally still leads a laboratory at the Miami VA.

VA PHOTO

Ludwig Gross, MD

Virologist Ludwig Gross, MD, in the 1950s and 1960s, discovered two different cancer-causing viruses at the Bronx VA Hospital (now the James J. Peters VA Medical Center).

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

Edward Freis, MD

In 1964, Edward Freis, MD, launched the first multicenter, double‐blind, randomized placebo‐controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of antihypertensive drugs in preventing or delaying serious cardiovascular events and organ damage. The study was conducted among more than 500 patients at 17 centers, and demonstrated that early treatment of high blood pressure with these drugs could save lives.

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

These are just a handful of the trailblazing VA researchers who have transformed medicine. Yalow and Schally, along with former Palo Alto VA researcher Ferid Murad, MD, PhD, are the VA’s recipients of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Along with Oldendorf, Starzl, Gross, Freis, and DeBakey, they are also winners of the Lasker Clinical Research Award, one of the most prestigious science prizes in the world. The Lasker was renamed to honor DeBakey – the Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award – in 2008.

Freis’s hypertension drug trial was groundbreaking in more than one way: Its success led to the 1972 establishment of VA’s Cooperative Studies Program, which is charged with coordinating multicenter clinical trials that evaluate novel therapies or new uses for existing treatments. It was an early-21st-century VHA-wide clinical trial involving nearly 39,000 participants at 156 VA Medical Centers, for example, that led to FDA approval of a shingles vaccine.

AN EVOLVING RESEARCH PROGRAM; A LEARNING HEALTH CARE SYSTEM

The evolution of VA research has been influenced by several factors: Veterans from different conflicts, for example, have had different health care needs. High rates of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C infections among Vietnam Veterans led to an increasing focus on these diseases by VA researchers. As traumatic brain injury (TBI) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) became known as the “signature injuries” of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts, the VA mobilized considerable resources, often in partnership with the Department of Defense, to gain insights and seek solutions. VA researchers have helped shape the medical community’s basic understanding of the disorder, publishing and disseminating some of the first evidence of PTSD-related biomarkers.

VA’s research programs have also changed to meet the special needs of its Veteran patient population as it ages: Beginning in 1975, to accommodate aging World War II and Korean War Veterans, VA began training interdisciplinary teams of specialists, and Congress later authorized Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Centers.

The Veterans Health Administration did not solicit or approve this content s

Changes to the way VHA delivers health care have also influenced the focus of VA research: In the 1990s, as the VHA began to increase its emphasis on primary and preventive care, rather than the hospital-based model, VA’s clinician researchers became key collectors of population-based data to document the impact of these changes. While clinical, biomedical, and rehabilitative studies had always been an important focus of VA’s research program, these new investigations of the quality, safety, and efficacy of care – conducted by a Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Service that traced its roots to the 1950s – have become increasingly important, particularly as more Veterans seek care from community providers under the Veterans Choice Program.

Technician Yasamin Azadzoi processes samples in the Million Veteran Program biorepository in Boston, Massachusetts.

In 1998, aided by a trove of data available from electronic health records, the VA established a new initiative aimed at translating research in high-priority areas into clinical practice: the Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI). QUERI has supported nearly 400 studies that inform the implementation of best practices in clinical care, including the nationwide deployment of integrated primary care mental health services and a national registry for monitoring outcomes of cardiac catheterization.

VA researchers have also capitalized on – and often participated in the development of – technological innovations. In the 1980s, a team of researchers led by Murray Jarvik, MD, PhD, and supported by both the VA and the University of CaliforniaLos Angeles, experimented with the transdermal absorption of tobacco compounds, and ultimately invented the nicotine patch, a method of nicotine replacement therapy that helps reduce withdrawal symptoms associated with quitting smoking. VA investigators have also been at the forefront of prosthetics research and development: the “Seattle Foot,” attachable to either a below- or above-the-knee prosthetic leg, was developed by VA researchers and released in the mid-1980s. Its simple design allows lower-limb amputees to run and jump.

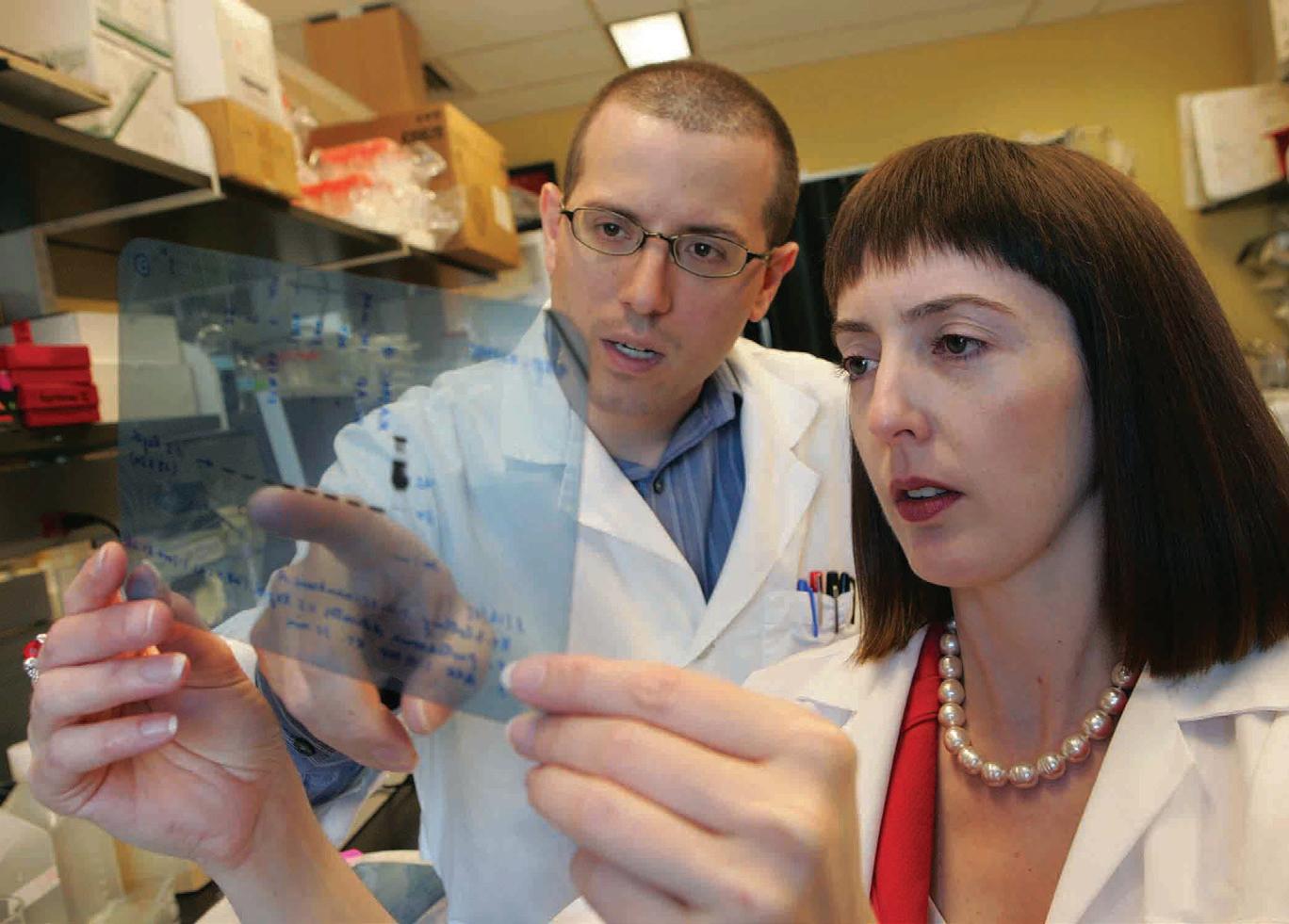

Melina Kibbe, MD, today dean of the University of Virginia School of Medicine, won a 2008 Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers for her VA research focused on nitric oxide. In this 2009 photo, she reviews a lab image with Nick Tsihlis, PhD, at the Jesse Brown VA Medical Center in Chicago, Illinois.

The completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003 led to a transformational effort within VHA: the Million Veteran Program (MVP). So far nearly 850,000 Veterans have volunteered to provide genetic, military service, lifestyle, and health information to the largest database of its kind in the world, an integrated health and genomic database tied to the nation’s largest health care system. Several studies of the MVP cohort have been completed or are underway, examining the role genes play in cardiovascular risk, anxiety, substance abuse, metabolic disorders, Gulf War illness, kidney disease, PTSD, schizophrenia, age-related macular degeneration, and other diseases or disorders.

Investigators in these studies examine genetic and other data from anonymous blood and tissue samples, donated by Veteran volunteers and stored at the Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center (MAVERIC) in Boston. The ability to sequence genomic information has anchored several initiatives aimed at discovering drugs or therapies that target specific genetic variations. New health care initiatives, such as the National Precision Oncology Program, launched in 2016, and the Precision Medicine in Mental Health Care (PRIME) Program, have been built on these research efforts.

Many leading-edge technological breakthroughs by VA researchers have been in the field of neuroprosthesis and brain-computer interfaces: Using digital technology, researchers have been able to simulate the activity of both sensory and motor neurons, with surprising results. Probably the highest-profile demonstration of these capabilities occurred in 2011, when a team including VA researchers demonstrated that people with tetraplegia, using a brain-computer interface, could control a robotic arm to perform basic tasks. These advances have helped VA researchers explore a new realm of capabilities for prosthetics, many of which were developed with their input.

One of the most important aspects of VA’s research program may be the way it leads to a direct and immediate enhancement of the care Veterans receive. It’s a largely intramural program: Investigators can lead VA research projects only if they have at least a 60 percent commitment to the VHA system; and because more than half of principal investigators are also VA clinicians, they have a close personal understanding of the health care needs of Veterans, and of the system that serves them. It’s a relationship that rewards researchers and Veterans alike: a team of the highest-caliber professionals, leaders in their fields, collaborating to advance the state of the art and provide the best possible medical care to American Veterans.