European Prints from the Wetmore Collection

September 12 – December 21, 2024

We are so pleased to present Ink and Time: European Prints from the Wetmore Collection in the Museum’s Bellarmine Hall Galleries to kick off a fall semester which finds both our Walsh and Bellarmine Galleries focused on printmaking. This exhibition of Renaissance and Baroque prints is the second in the Museum’s history to have been co-curated with Fairfield University undergraduate students. It is the product of Michelle DiMarzo’s Museum Exhibition Seminar, which she introduced in 2021, and which resulted in the extremely well-received 2023 exhibition Out of the Kress Vaults: Women in Sacred Renaissance Painting. After that great success, we decided to make this a semi-regular part of the Museum’s exhibition calendar. The course is now taught every two years through the Art History program, with the resulting exhibition presented in the following year (I am excited to share with you that the next exhibition in this series will be focused on Egyptomania, curated by Megan Paqua, and presented in fall 2026!).

We are so very grateful to Connecticut College for sharing the prints in this exhibition with us, and for allowing the students to have a hands-on experience with them during their seminar. At the College this loan was graciously facilitated by Benjamin Panciera, Ruth Rusch Sheppe ‘40 Director of Special Collections and Archives, and Karen Gonzalez Rice, PhD, Associate Professor of Art History.

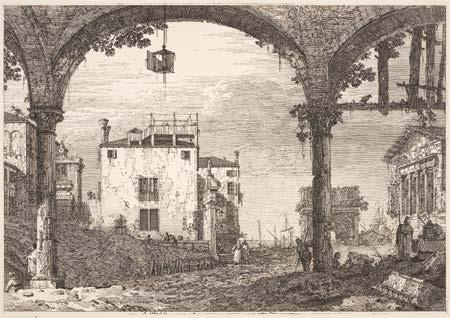

Ink and Time is nostalgic for me, as it was inspired by my own experiences as an undergraduate art history major at Connecticut College using the Wetmore Collection as a student. Several of the prints that have stayed with me in my mind to this day are happily included in this exhibition, with my personal favorite being Portico with a Lantern (cat. 52, facing page) by Canaletto.

We are extremely grateful to the Samuel H. Kress Foundation for their generous support of this exhibition. Their grant will allow us to present an incredible array of hands-on workshops and demonstrations designed to provide our students and community members a deep engagement with these Old Master prints, as much in terms of their technological refinement as their artistic power.

I would like to thank Michelle DiMarzo, PhD for her tireless work on this exhibition, and for her careful shepherding of this project from its inception – through the seminar spent working with her students, to the writing of the informative essay and label texts, and to its final installation and presentation to the public.

We hope you will join us for the wonderful array of associated programming which Dr. DiMarzo has created to complement the exhibition, and which will be presented throughout the fall semester. For information on these programs, please check the listings at the end of this brochure.

Thanks as always go to the exceptional Museum team for their hard work in bringing this exhibition and its associated programming to life: Michelle DiMarzo, Curator of Education and Academic

Engagement (and Exhibition Curator); Megan Paqua, Museum Registrar; and Heather Coleman, Museum Assistant. We are grateful for the additional support provided across the University by Edmund Ross, Susan Cipollaro, and Dan Vasconez, as well as by our colleagues in the Quick Center for the Arts and the Media Center. Finally, we thank Laura Gasca Jiménez, PhD for preparing the Spanish translations of the exhibition materials; her continued partnership enables us to make our materials available bilingually.

~ Carey Mack Weber Frank and

Clara Meditz

Executive Director

Printmaking, with some exceptions, has always been a fundamentally collaborative enterprise, as artists, engravers, and printers combined their talents to produce works of extraordinary beauty on simple pieces of paper. This exhibition is likewise the result of a series of collaborations, without which it could not have come to fruition. First, our colleagues at Connecticut College generously agreed to loan us a large group of works from the Wetmore Collection for a period of two years (rather than the more typical exhibition loan period of just 3-4 months). This paved the way for the group of energetic students (Katherine Antico ’25, Priya Banerjee ’25, Caleigh Hopkins ’24, Arabella Resto ’24, and Blessed Stephen ’26) enrolled in my Museum Exhibition Seminar in Fall 2023 to help me develop the show, refine its checklist, and begin research, all while learning directly from the prints themselves. And finally, no exhibition would have been possible without the help of my Fairfield colleagues in the Museum and beyond.

This exhibition presents a group of woodcuts, engravings, and etchings from the late 15th through late 18th centuries. The Wetmore Collection was assembled in the early 20th century by New London, Connecticut native Fanny Wetmore, and bequeathed to Connecticut College in 1930. Although little is known of Wetmore herself, her collecting activities place her within a tradition dating back to the rise of printmaking in early modern Europe. The surging production of prints by the beginning of the 16th century represented a sea change for both artists and consumers. For artists, prints provided additional revenue, increased their personal fame, and offered greater latitude for experimentation outside the traditional patronage structure. For consumers, prints represented access to visual art on an unprecedented scale; even those who would never have been able to commission an independent work from a great artist could now readily obtain an engraving or an etching. Prints were easily transported, could be pasted up on walls or into albums, and even large collections of them took up relatively little room. And, with the rise of reproductive printmaking, even prints based upon geographically distant or physically inaccessible artworks could be added to the collector’s “paper museum.”

Over these centuries, European printmaking developed through continual technical experimentation on the part of artists, who sought new ways to achieve their own pictorial aims, as well as publishers, who sought to satisfy the demands of the growing market for prints. The relationships between the individuals who made these prints possible were frequently acknowledged in bits of abbreviated Latin sprinkled around their borders – clues that we, the educated print consumer, were expected to recognize. Part of the goal of this exhibition has been to decode some of this hidden language of collaboration, while placing the prints and their makers in the context of the flourishing print culture of early modern Europe (see also the Glossary at the conclusion of this essay).

Printmaking in the West arose around the year 1400, starting with woodcuts. Woodcuts are a relief process; the carver must remove all of the wood from the block except for the lines they want to print, which are left standing up (“in relief”) from the block’s surface. While it was too soon to speak of mass production in the modern sense, this was the first time that visual images could be readily and cheaply reproduced. The earliest examples of the new process included simple religious images and playing cards, and although we are accustomed to thinking of prints as black-and-white, they were frequently painted, either by hand or with the use of stencils.

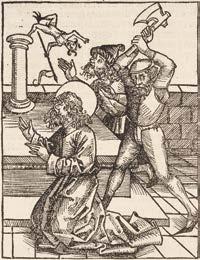

The printing press introduced by Johannes Gutenberg in the middle of the 15th century also relied on a relief process, as the letterforms of moveable type stood in relief from their metal surfaces. This meant that woodcuts could easily be printed alongside text, and illustrated books accordingly became common. Perhaps the bestknown early example was the Nuremberg Chronicle , an ambitious volume of “universal history” written by scholar Hartman Schedel and published in 1493 by Anton Koberger, for which the workshop of Michael Wolgemut provided more than 1,800 illustrations (cat. 4, left). Luxury editions of the Nuremberg Chronicle featured hand-coloring.

Since carving a woodblock required specialized training, most artists relied on skilled craftsmen who could translate their drawings onto the block. Albrecht Dürer, who trained in Michael Wolgemut’s workshop as a young man, may have been an exception in producing at least some of his own woodblocks. In The Holy Trinity (cat. 13, p. 6), for example, which is often considered Dürer’s most technically-proficient woodcut, the gray midtones are produced by criss-crossing lines of extraordinary delicacy.

While the practice of painting individual prints continued, artists began to experiment with methods of adding color into the printing process itself. Around 1509, the Italian Ugo da Carpi developed a technique for dividing a design into multiple woodblocks that could be printed in a range of tones, which mimicked the effect of a drawing with wash, or diluted ink. The Italian term given to this

new process, chiaroscuro , refers to the tonal contrast of light and shadow. Lucas Cranach’s chiaroscuro woodcut Saint Christopher (cat. 5, right) was printed in 1509, but some later printings show a date of 1506 in the cartouche in the tree – evidently an effort by the German artist to take credit for the new process.

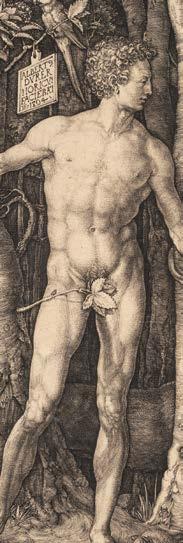

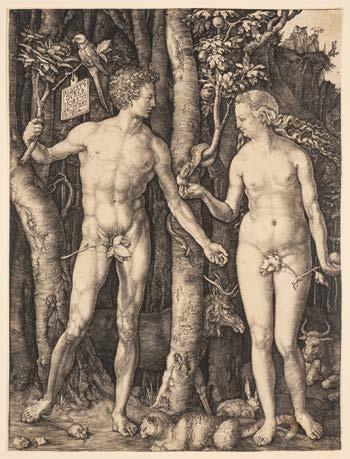

The intaglio printmaking processes (engraving, etching, and drypoint) would come to supplant relief printmaking during the 16th century. The term intaglio comes from the Italian intagliare , “to carve,” and printmakers adapted techniques that had long been used by European goldsmiths and armor-makers. In engraving, artists used a tool called a burin to remove thin strips of metal from a polished metal plate, carefully rotating the plate on a cushioned surface as they kept their hands steady. The engraved line could vary in width depending on the pressure applied. Dürer’s control of line is evident in Adam and Eve (cat. 9, p. 8), creating masterful distinctions in the textures of skin, bark, and fur.

Engraving required training, and furthermore imposed limitations on the freedom of the artist’s hand as it moved across the plate. For this reason, etching – which relied on acid to dissolve metal, as opposed to removing it by physical effort – became increasingly popular among artists in the later 16th and 17th centuries. Using a sharp needle-like tool, the artist scratched his or her design on a copper plate prepared with a thin layer of acid-resistant wax, called ground. The plate’s surface would then be exposed to acid, and only areas where the protective ground had been removed by the needle would be affected, with the acid “biting” the lines of the design into the metal. This technique allowed artists to imitate much more closely the effect of a drawing, and further reduced the barriers to entry to printmaking.

Artists frequently combined the two methods, laying in strong engraved lines first before working on the areas to be etched. Although etching did not permit variability in the width of the line, artists

quickly began to experiment with ways to deepen the tonal range of their prints. After etching the plate, they added ground to areas they did not want to darken, a process known as stopping out. When they returned the plate to the acid, the exposed lines would be etched even more deeply, a process called double-biting.

Artists could also add final touches in drypoint, scratching the plate’s bare surface with the needle so that metal was displaced and pushed to one side of the line, creating a burr. When the plate was inked, these burrs would hold on to much more ink than the etched line alone, producing a softer, richer line in the printed image. The downside of drypoint was its fragility, as far fewer impressions could be produced from the plate before the burr would begin to wear away.

In the Three Trees (cat. 33, above), the 17th-century Dutch artist Rembrandt combined engraving, etching, and drypoint to remarkable effect. He used double-biting to deepen the shadows of the lower zone, while stopping-out protected the lighter areas. He used a burin to reinforce the lines creating the shadows at lower right, where a pair of lovers can just be glimpsed hiding in the bushes. With the drypoint needle, he shaped the masses of clouds, and used a straightedge to incise the shafts of light breaking through. Scholars have even detected in the fields of the middle ground (see fig. 1, right) areas where Rembrandt was experimenting with flicking spots of an acid (like sulfur) onto the plate to create tiny pits that could hold more ink and create greater tone – this is before the invention of aquatint.

An offshoot of etching, aquatint was the first printmaking process capable of producing tonal effects. First invented in the mid-17th century, it did not achieve widespread use by artists until the 18th century. Powdered rosin would be sprinkled across a plate’s surface and subsequently fused by heat. The fused particles would act as a ground, so when the plate was placed in acid, only the areas around

them would be etched. The resulting tonal variation could be deepened in selected areas by re-submerging the plate after stopping out those areas to be printed lighter. Aquatint required a great deal of advance planning and timing, but the benefits it provided to artists were immense in recreating painterly transitions of light and shadow, such as in the clouds behind the female figure in this print by the German artist Maria Catharina Prestel (cat. 43, left).

Although intaglio printmaking generally offered much more control to the artist or engraver, the actual printing process was more complicated than it had been for relief prints. After ink was applied to the plate, its surface had to be carefully wiped – a timeconsuming process – until ink remained only in the engraved or etched lines. Ink left on the surface of the plate would show up as “plate tone” on the sheet (though artists realized that this, too, was something they could experiment with). Specialized intaglio presses had to exert enough pressure to transfer ink from the plate onto a sheet of dampened paper. The pressure of that process also produces a “plate mark,” or the impression of the sheet of metal outside the design.

Some artists produced their prints in multiple states, using the press as a trial process. Rembrandt is well-known for producing prints in multiple states; after each he would return to the plate to make revisions, often printing in larger numbers as he became more satisfied with the work’s development. This impression of Self-Portrait Etching at a Window (cat. 36, facing page) represents the fourth and likely final state of this print (a proposed fifth state may reflect alterations to the plate after Rembrandt’s death). Among the artist’s final changes was the addition of the landscape; this area

of the plate had been marred by “foul biting,” or unplanned marks caused by the failure of the ground to resist the acid, so adding the landscape allowed him to incorporate and conceal these marks in the final state.

Both woodblocks and intaglio plates were typically used to produce prints until they came too worn down or damaged to produce a good impression. Even then, enterprising publishers might have a block re-carved, or intaglio lines reinforced, to protect their stockin-trade. For example, when the publisher Andrea Andreani reprinted a chiaroscuro woodcut after Raphael’s The Miraculous Draft of Fishes (cat. 24, above) he inserted a new signature block at lower left (fig. 2, below) that gave his own monogram, the city of Mantua, and the date of 1609. While Raphael was still given pride of place as the “inventor,” the name of the original 16th-century printmaker Niccolò Vicentino was omitted.

Other reprintings involved more significant changes to the composition. Rembrandt’s copper plates remained in circulation for more than a century after his death, as posthumous printings helped satisfy the ever-growing demand for his work among collectors in northern Europe and England. It was not uncommon for these plates to be reworked to reinforce the lines of Rembrandt’s designs, which could not hold up to large numbers of impressions being pulled from them, particularly the drypoints. In 1775, the English collector and amateur artist Captain William Baillie purchased the plate for the Hundred Guilder Print , one of Rembrandt’s most successful compositions, from a painter named John Greenwood. Baillie “restored” the plate, significantly reworking it in the process, and printed a new edition of 100 impressions. Later, Baillie took things a step further, cutting the reworked plate into four sections, each of which could be printed and sold individually, as seen here, with the four pieces reassembled. (cat. 35, facing page).

Prints tend to be dotted with bits of text about the edges and outside the boundary of the image itself. The simplest of these are monograms or signatures identifying the artist, such as Dürer’s iconic AD (fig. 3, right). As printmaking became more widespread, it became common to include inscriptions that provided information on a print’s authorship. The educated consumer would be expected not only to recognize such Latin terms as pinxit (painted), excudit (published), and sculpsit (engraved) but to recognize them in abbreviated forms like pinx , exc., or sc .

For example, the inscription RAPHA /URBI /INVEN/ MAF appears at the left edge of the Massacre of the Innocents (cat. 20, facing page), illusionistically engraved into the masonry of the low wall. The expectation is that we will expand that inscription into RAPHA[el] / URBI[nas] / INVEN[it] / MA[rcantonio]F[ecit], and understand it to meant that Raphael “invented” the composition, while Marcantonio Raimondi “made” the engraved plate.

While helpful, inscriptions must still be interpreted contextually. For example, art historians of the past tended to assume that Marcantonio simply executed engravings based on highly-finished designs Raphael provided him, but more recent scholarship has emphasized their collaboration as an active, reciprocal exchange.

In other cases, inscriptions might conceal true authorship. The inscriptions at the bottom of Allegory of Virtue Overcoming Envy (cat. 43, p. 10) include, at lower left, Ligozzi Del[ineavit] and at lower right, J. G. Prestel Sc[ulpsit] ), which would appear to attribute it to Johann Gottlieb Prestel, after a drawing by Jacopo Ligozzi in a German collector’s cabinet. However, scholars have recently re-assigned this print to Prestel’s wife, Maria Katharina, who worked alongside him in his studio and later moved to London to establish herself as an independent artist.

In The Good Samaritan (cat. 1, right), the inscription tucked into the decorative border (Ioha[nnes]. bol. inuen[i]t. Eduardus ab hoeswinkel. excu[dit]./ A. collaert. fe[cit] ) tells us that Hans Bol created the design, Adriaen Collaert engraved the plate, and Eduard van Hoeswinckel published the resulting print. However, van Hoeswinckel had in fact died a year earlier; his wife Anna simply continued the publishing operation in his name.

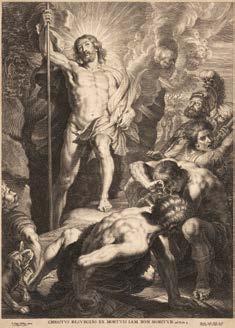

Reproductive prints, or prints based upon a preexisting artwork in another medium, usually include inscriptions linking the print to its source. The bottom margin of the Resurrection of Christ (cat. 29, p. 16) includes a Latin quotation from Romans 6:9: Christus resurgens ex mortuis iam non moritur (Christ, rising from the dead, will die no more). At lower left the inscription P. Paulus Rubbens Cat. 1

pinxit. / S. a. Bolswert fecit tells us that this is a reproductive engraving after a painting by Peter Paul Rubens (in fact the central portion of a triptych in the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp). At the lower right, Martinus vanden Enden excud. / Antwerpae Cum privilegio Regis adds the name of the print’s publisher, Martin van Enden, as well as the privilegio , an early form of copyright.

In contrast, the etching of St. Francis (cat. 28, facing page) simply notes P. P. Rubbens on the rock at lower left. Adapted from a painting commissioned for a Franciscan church in Ghent, the print is likely an example of the many “unauthorized” reproductions after Rubens’ work, which irritated the artist enough that he began to organize the creation of prints “in-house.” By employing artists like Bolswert, Rubens could ensure that the reproductive prints were faithful to his own style and protected by copyright (as well as securing his own share of profits from their sale).

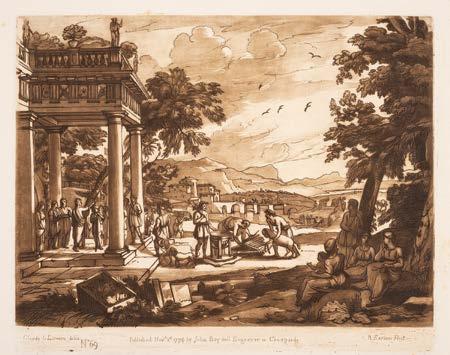

In the case of Saul Anointing David (cat. 46, p. 18) the inscription includes even the month and date of its publication, as well as the neighborhood of the publisher: Claude le Lorrain delin[eavit] / No. 69 / Published Nov[embe]r 1st 1774 by John Boydell Engraver in Cheapside / R Earlom fecit . This print formed part of a remarkably ambitious project known as the Liber Veritatis , which sought to capitalize on the 18th-century English taste for the romantic paintings of the 17th-century painter Claude Lorrain. Boydell, the publisher, commissioned Richard Earlom to reproduce an album of 200 pen and wash drawings that Claude had used to record his own paintings (the album having entered England earlier in the century in the collection of the Duke of Devonshire).

While inscriptions on European prints were never universal nor fully standardized, their prevalence throughout the early modern period suggests the desire on the part of those involved to see their contributions recognized and their names linked to the objects of beauty they helped to create.

~ Michelle DiMarzo, PhD

Aquatint: The was first printmaking process capable of reproducing tonal effects. Powdered rosin was sprinkled across a copper plate’s surface and subsequently fused by heat to form a ground. When the plate was placed in acid, only the areas around the fused particles would be etched, creating subtle variations in tone.

Burin: The tool used by engravers to incise copper plates. It features a rounded handle and long metal shaft ending in a very sharp, lozenge-shaped tip.

Burr: A thin line of metal, displaced by an etcher’s needle from a copper plate (rather than dissolved away).

Drypoint: An intaglio technique, frequently combined with etching, in which the artist scratched the bare, unprotected surface of the plate. When the plate was inked, the resulting burrs would hold on to much more ink than the etched line alone, producing a softer, richer line in the printed image.

Engraving: An intaglio printmaking process in which the artist used a burin to incise lines into a metal plate (usually copper). The plate would be balanced on a cushioned surface and carefully rotated, as the engraver held his hand steady.

Etching: An intaglio printmaking process that relied on acid to dissolve metal, as opposed to removing it by physical effort through engraving. Using a sharp needle-like tool, the artist scratched his or her design on a copper plate prepared with a thin layer of acid-resistant wax, called ground. The plate’s surface would then be exposed to acid, and only areas where the protective ground had been removed by the needle would be affected, with the acid “biting” the lines of the design into the metal.

Impression: An individual piece of paper bearing an artist’s design. The number of impressions that could be produced before the block or plate deteriorated varied depending on the process used. The most fragile with drypoint plates, which might produce only 100 impressions before the burr began to wear away.

Intaglio: From the Italian intagliare (“to carve”), a range of printmaking processes that incise lines into a metal surface. In printing, ink would be applied to the plate and then carefully wiped away until ink remained only in the engraved or etched lines. Specialized intaglio presses had to exert enough pressure to transfer the inked lines onto a sheet of dampened paper.

Mezzotint: An intaglio technique in which the artist used a tool called a rocker to work over an area of the plate until it was completely roughened and would print uniformly dark. Then, he selectively burnished areas to create lighter and lighter tones. While this dark-to-light method required a significant amount of labor, it was highly effective for reproducing painterly and atmospheric effects.

Relief: Any printmaking process, such as woodcut, in which the lines of the design are raised above the surface of the block.

Reproductive print: A print made after a pre-existing artwork, often one by another artist. The early print historian Adam Bartsch (1757-1821) coined the term peintre-graveur, or “painter-engraver” to privilege those artists who designed their own original prints while signaling the perceived lower status of reproductive printmakers – a division more recent scholarship has tried to avoid.

State: Refers to all impressions produced within an identifiable stage of a print’s development. Artists might print a set of trial proofs before returning to the copper plate to make further alterations, producing an additional state. Some artists, like Rembrandt, frequently produced multiple states.

Woodcut: A relief printmaking process in which a carver removed all of the wood from a block except for the lines of the artist’s design. Ink applied to the surface with a brush would only cling to the raised lines.

Bartrum, Giulia, British Museum, British Museum, and Trustees. German Renaissance Prints 1490-1550. London: Published for the Trustees of the British Museum by British Museum Press, 1995.

Dackerman, Susan. Painted Prints: The Revelation of Color in Northern Renaissance & Baroque Engravings, Etchings & Woodcuts . University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2002.

Griffiths, Antony. Prints and Printmaking: An Introduction to the History and Techniques . 2nd ed. London: British Museum Press, 1996.

Hults, Linda C. The Print in the Western World: An Introductory History. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996.

Landau, David, and Peter Parshall. The Renaissance Print: 1470-1550. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994.

Lincoln, Evelyn. The Invention of the Italian Renaissance Printmaker. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

Mayor, A. Hyatt. Prints and People: A Social History of Printed Pictures. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013.

Pon, Lisa. Raphael, Dürer, and Marcantonio Raimondi: Copying and the Italian Renaissance Print . New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn. Rembrandt: Painter as Printmaker. Denver, Co.: Denver Art Museum, 2018.

Witcombe, Christopher. Copyright in the Renaissance: Prints and the Privilegio in Sixteenth-Century Venice and Rome . Boston: Brill, 2004.

Zorach, Rebecca, and Elizabeth Rodini. Paper Museums: The Reproductive Print in Europe, 1500-1800. Chicago: David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, 2005.

All artworks are part of the Wetmore Collection unless otherwise indicated, and are courtesy of Connecticut College.

1. Adriaen Collaert (Flemish, ca. 1560-1618)

after Hans Bol (Netherlandish, 1534-1593)

Eduard van Hoeswinckel (South Netherlandish, d. 1583), publisher

The Good Samaritan , 1584

Engraving

5 ½ x 8 ⅜ inches (image)

5 ¾ x 8 ½ inches (sheet)

2. Adriaen Collaert (Flemish, ca. 1560-1618)

after Marten de Vos (Flemish, 1532-1603)

The Crucifixion , 1598-1618

Engraving

6 ½ x 8 ½ inches (image)

7 ¼ x 8 ½ inches (sheet)

3. Johann Theodor de Bry (Franco-Flemish, 1561-1623)

after Titian (Italian, ca. 1488-1576)

The Triumph of Christ , ca. 1600

Engraving

3 ⅛ x 15 inches (sheet)

4. Michael Wolgemut (German, 1432/1437-1519) or Wilhelm Pleydenwurff (German, ca. 1460-ca. 1494)

Martyrdom of Matthew, from the Nuremberg Chronicle , ca. 1493

Woodcut

5 ⅛ x 4 ¼ inches (sheet)

5. Lucas Cranach the Elder (German, 1472-1553)

Christ before Caiaphas , ca. 1509

Hand-colored woodcut

7 ¾ x 9 ¾ inches (sheet)

6. Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471-1528)

Saint Christopher, 1503-4

Woodcut

8 ⅝ x 5 ⅞ inches (sheet)

7. Lucas Cranach the Elder (German, 1472-1553)

Saint Christopher, 1509

Chiaroscuro woodcut

10 ½ x 7 ⅝ inches (sheet)

8. Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471-1528)

Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse , 1496-1498

Woodcut

15 ½ x 10 ⅞ inches (image)

15 ¾ x 11 ¼ inches (sheet)

9. Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471-1528)

Adam and Eve , 1504

Engraving

10 x 7 ½ inches (sheet)

10. Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471-1528)

Saint Jerome in His Study , 1514

Engraving

9 ½ x 7 ½ inches (sheet)

11. Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471-1528)

Saint Jerome in the Wilderness , 1496

Engraving

12 ¾ x 8 ⅞ inches (sheet)

12. Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471-1528)

The Coronation of the Virgin , 1510

Woodcut

15 ¼ x 11 inches (sheet)

13. Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471-1528)

The Holy Trinity , 1511

Woodcut

15 ¼ x 11 inches

14. Lucas van Leyden (Netherlandish, ca. 1494-1533)

Saint John the Baptist , 1513

Engraving

3 ⅜ x 4 ⅜ inches (sheet)

15. Lucas van Leyden (Netherlandish, ca. 1494-1533)

Saint Peter and Saint Paul , 1527

Engraving

4 x 5 ½ inches (sheet)

16. Lambert Suavius, also called Lambert Zuttman (Netherlandish, 1510-1574/6)

Saint Philip (?), ca. 1545

Engraving

7 ⅜ x 3 ¼ inches (sheet)

17. Marcantonio Raimondi (Italian, ca. 1470/82-ca. 1527/34)

after Raphael (Italian, 1483-1520)

Virgin and Child Seated on Clouds , ca. 1511-1515

Engraving

7 x 5 ⅛ inches (sheet)

Black Collection, Connecticut College

18. Giovanni Jacopo Caraglio (Italian, ca. 1500/05-1565)

School of an Ancient Philosopher, ca. 1525

Engraving

5 ½ x 6 inches (sheet)

19. Giuseppe Porta, called il Salviati (Italian, ca. 1520-1575)

Academy of Arts and Sciences , ca. 1540

Engraving on wood

9 ⅜ x 7 ¾ inches (sheet)

20. Marcantonio Raimondi (Italian, ca. 1470/82-ca. 1527/34)

after Raphael (Italian, 1483-1520)

Massacre of the Innocents , ca. 1511-14

Engraving

10 ½ x 16 ¾ inches (sheet)

Black Collection, Connecticut College

21. Giorgio Ghisi (Italian, 1520-1582)

after Francesco Salviati (Italian, 1510-1563)

The Visitation , ca. 1540s

Engraving

19 ¾ x 12 ½ inches (sheet)

22. Giulio Bonasone (Italian, ca. 1510-after 1576) after Michelangelo (Italian, 1475-1564)

Antonio Salamanca (Spanish, ca. 1500-1562), publisher

The Last Judgment , ca. 1546-1550

Engraving

17 ⅝ x 23 inches (sheet)

23. Ugo da Carpi (Italian, active 1502-1532)

after Raphael (Italian, 1483-1520)

Ananias Struck Dead , 1518

Chiaroscuro woodcut

9 ¾ x 15 inches (sheet)

Black Collection, Connecticut College

24. Niccolò Vicentino (Italian, active ca. 15401550) after Raphael (Italian, 1483-1520)

Andrea Andreani (Italian, 1558/9-1629),

publisher

The Miraculous Draught of Fishes , 1609

Chiaroscuro woodcut

9 ⅛ x 13 ¼ inches (sheet)

25. Guido Reni (Italian, 1575-1642)

Holy Family , ca. 1590-1610

Etching

9 ⅞ x 7 ⅝ inches (image)

10 ⅛ x 8 ¼ inches (sheet)

26. Jacques Callot (French, 1592-1635)

The Assumption of the Virgin , ca. 1620s

Etching

3 ⅝ x 2 ⅝ inches (sheet)

27. Federico Barocci (Italian, 1528-1612)

Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata , ca. 1581

Etching and engraving

8 ⅞ x 5 ¾ inches (sheet)

28. Willem Pietersz Buytewech (Dutch, 1591/1592-1624)

after Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577-1640)

Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata , ca. 1613-1614

Etching

5 ⅝ x 4 inches (image)

5 ⅞ x 4 ½ inches (sheet)

29. Schelte Bolswert (Dutch, ca. 1586-1659)

after Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577-1640)

Martinus van Enden (Flemish, active 17th c.),

publisher

The Resurrection of Christ , ca. 1630-1645

Engraving

15 ¾ x 11 ½ inches (image)

16 ½ x 11 ¾ inches (sheet)

30. Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669)

Saint Jerome Kneeling in Prayer, 1635

Etching

4 ½ x 3 ¼ inches (sheet)

31. Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669)

Saint Jerome in a Dark Chamber, 1642

Etching and drypoint

6 x 6 ⅞ inches (sheet)

32. Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669)

Self-Portrait in Slant Fur Cap , 1631

Etching

2 ¼ x 2 ⅛ inches (sheet)

33. Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669)

Three Trees , 1643

Etching, drypoint, and burin

8 ¼ x 10 ⅞ inches (image)

8 ½ x 11 ¼ inches (sheet)

34. Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669)

Christ Preaching (La petite Tombe), ca. 1652

Etching, drypoint, and burin

6 ⅛ x 8 ⅛ inches (sheet)

35. Capt. William Baillie (English, 1723-1792)

after Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669)

Hundred Guilder Print , 1775-1800

Etching, drypoint, and burin

Upper left: 2 x 3 inches (image); 2 ½ x 3 ⅜ inches (sheet)

Lower left: 5 ½ x 3 inches (image); 6 x 3 ½ inches (sheet)

Center: 11 x 7 ½ inches (image); 11 ½ x 8 inches (sheet)

Right: 7 ½ x 4 ⅞ inches (image);

8 ⅜ x 5 ⅞ inches (sheet)

36. Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669)

Self-Portrait Etching at a Window, 1648

Etching, drypoint, and burin

6 ⅛ x 5 ⅛ inches (image)

6 ⅜ x 5 ¼ inches (sheet)

37. Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669)

Woman Lying Down , 1658

Etching, drypoint, and burin

3 ⅜ x 6 ¼ inches (sheet)

38. Salvator Rosa (Italian, 1615-1673)

Jason and the Dragon , ca. 1663-64

Etching and drypoint

13 ⅜ x 8 ⅝ inches (sheet)

39. Nicolaes Berchem (Dutch, 1620-1683)

Group of Horses , ca. 1640-83

Etching

6 ⅞ x 4 ¾ inches (sheet)

40. Simon de Vlieger (Dutch, 1601-1653)

Four Turkeys , 17th century

Etching

5 x 6 ⅛ inches (image)

5 ⅜ x 6 ⅝ inches (sheet)

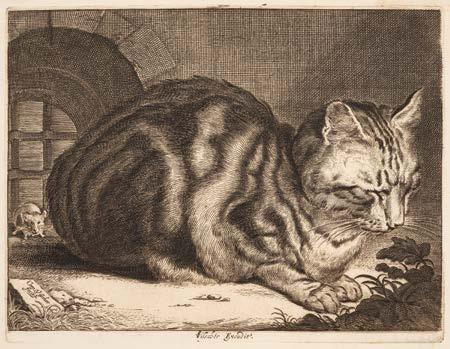

41. Cornelis de Visscher (Dutch, ca. 1629-1658)

Sleeping Cat , 1657

Engraving

5 ¼ x 7 ⅛ inches (image)

6 ½ x 8 ⅛ inches (sheet)

42. John Simon (English, ca.1675-1751)

after Francis Barlow (English, 1622-1704)

Birds: jay, woodpecker, wood-pigeons, woodcock, curlew, bittern , ca. 18th century

Engraving

5 ⅞ x 8 ⅝ inches (image)

9 ⅝ x 11 ⅞ inches (sheet)

43. Maria Katharina Prestel (German, 1747-1794) after Jacopo Ligozzi (Italian, 1547-1627)

The Triumph of Truth over Envy , 1780

Etching and aquatint in brown and ochre ink, touched with gold leaf

12 x 9 inches (sheet)

44. Angelica Kauffmann (Swiss, 1741-1807)

John Boydell (English, 1720-1804), publisher

Girl Reading , 1770, printed 1781

Etching

6 ¼ x 4 ⅝ inches (image)

6 ⅝ x 4 ⅞ inches (sheet)

45. John Boydell (English, 1720-1804)

[Landscape with bridge and figures], ca. 18th century

Etching

5 ⅞ x 10 ⅛ inches (image)

6 ⅝ x 11 inches (sheet)

46. Richard Earlom (English, 1743-1822) after Claude Lorrain (French, 1604-1682)

John Boydell (English, 1720-1804), publisher

Saul Anointing David , 1774

Etching and mezzotint

7 ½ x 10 ⅛ inches (image)

10 ¾ x 15 ⅞ inches (sheet)

47. Claude Lorrain (French, 1604-1682)

Europa , 1634

Etching

7 ¾ x 10 ⅛ inches (image)

8 ⅝ x 11 ⅛ inches (sheet)

48. Claude Lorrain (French, 1604-1682)

Time, Apollo and the Seasons , 1662

Etching

7 ¼ x 10 inches (image)

7 ⅝ x 10 ¼ inches (sheet)

49. Claude Lorrain (French, 1604-1682)

The Landscape Painter, ca. 1638-41

Etching

4 ⅞ x 7 inches (image)

5 ⅝ x 7 ⅜ inches (sheet)

50. Giovanni Antonio Canal, called Canaletto (Italian, 1697-1768)

Market on the Molo , ca. 1735-1746

Etching

5 ⅝ x 8 ¼ inches (sheet)

51. Giovanni Antonio Canal, called Canaletto (Italian, 1697-1768)

Imaginary View of S. Giacomo di Rialto , ca. 1735-1746

Etching

5 ⅝ x 8 ⅜ inches (sheet)

52. Giovanni Antonio Canal, called Canaletto (Italian, 1697-1768)

Portico with a Lantern , ca. 1735-1746

Etching

11 ¾ x 17 inches (image)

12 ¾ x 17 ¾ inches (sheet)

53. Giovanni Antonio Canal, called Canaletto (Italian, 1697-1768)

View of Mestre , ca. 1735-1746

Etching

11 ⅝ x 16 ⅝ inches (image)

12 ¼ x 17 ¼ inches (sheet)

54. Giovanni Antonio Canal, called Canaletto (Italian, 1697-1768)

Imaginary View of Padua , ca. 1735-1746

Etching

11 ⅝ x 17 inches (image)

Sheet: 12 x 17 ¼ inches (sheet)

55. Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo (Italian, 1727-1804) after Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (Italian, 1696-1770)

Old Man Seen from the Front , 1770

Etching

5 x 4 inches (image)

8 x 6 ⅛ inches (sheet)

Events listed below with a location are live, in-person programs. When possible, those events will also be streamed on thequicklive.com and the recordings posted to the Museum’s YouTube channel. Register at: fuam.eventbrite.com

Thursday, September 19, Noon in-person, 1 p.m. streaming on thequicklive.com

Art in Focus: Albrecht Dürer, Adam and Eve , 1504, engraving

Bellarmine Hall, Bellarmine Hall Galleries

Thursday, September 26, 5 p.m.

Opening Night Lecture: Michelle DiMarzo, PhD, Exhibition Curator

Bellarmine Hall, Diffley Board Room and streaming on thequicklive.com

Thursday, September 26, 6-8 p.m.

Opening Reception

Bellarmine Hall, Bellarmine Hall Galleries and Great Hall

Thursday, October 10, Noon in-person, 1 p.m. streaming on thequicklive.com

Art in Focus: Marcantonio Raimondi and Raphael, Massacre of the Innocents , ca. 1511-1514, engraving

Bellarmine Hall, Bellarmine Hall Galleries and streaming on thequicklive.com

Tuesday, October 22, 5 p.m.

Lecture: Shirley M. Mueller, MD, author of Inside the Head of a Collector (2019)

Barone Campus Center, Dogwood Room and streaming on Vimeo

Presented in partnership with the Arts Institute and the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences

Thursday, November 14, Noon in-person, 1 p.m. streaming on thequicklive.com

Art in Focus: Rembrandt, Three Trees , 1643, etching, drypoint, and burin

Bellarmine Hall, Bellarmine Hall Galleries and streaming on thequicklive.com

Tuesday, November 19, 5 p.m.

Lecture: Rare and Everywhere: Making and Selling Prints in the Age of Rembrandt

Nadine Orenstein, PhD, Drue Heinz Curator in Charge of the Department of Drawings and Prints, Metropolitan Museum of Art Barone Campus Center, Dogwood Room, and streaming on thequicklive.com

Part of the Edwin L. Weisl, Jr. Lectureships in Art History, funded by the Robert Lehman Foundation

Thursday, December 12, Noon in-person, 1 p.m. streaming on thequicklive.com

Art in Focus: Maria Katharina Prestel, The Triumph of Truth Over Envy, 1780, etching and aquatint in brown and ochre ink, touched with gold leaf

Bellarmine Hall, Bellarmine Hall Galleries and streaming on thequicklive.com

Tuesday, December 17, 6:30 p.m.

Concert: Sacred Music a cappella

Connecticut Chamber Choir, led by Michael Ciavaglia DMA

Bellarmine Hall, Bellarmine Lobby and Great Hall

Space is limited and registration is required.

Printmaking Gallery Demonstrations

One-hour demonstration and discussion of materials and techniques with Master Printer Chris Shore (Center for Contemporary Printmaking). Space is limited and registration is required. Bellarmine Hall Galleries

• Thursday, October 10 Woodcut, 4 p.m. and 6:30p.m.

• Tuesday, October 29

Etching and Engraving, 4 p.m. and 6:30 p.m.

Printmaking Hands-on Workshops

Three-hour workshops led by Master Printer Chris Shore (Center for Contemporary Printmaking).

Supplies provided. Space is limited and registration is required.

• Thursday, November 7 Making Relief Prints, 5:30-8:30 p.m.

• Thursday, November 14 Making Engraved Prints, 5:30-8:30 p.m.

fairfield.edu/museum/ink-and-time

All events and programs are free and open,to the public, but registration is requested. Register at fuam.evenbrite.com or fairfield.edu/museum.

The Fairfield University Art Museum is deeply grateful to the following corporations, foundations, and government agencies for their generous support of this year’s exhibitions and programs. We also acknowledge the generosity of the Museum’s 2010 Society members, together with the many individual donors who are keeping our excellent exhibitions and programs free and accessible to all and who support our efforts to build and diversify our permanent collection.