Welcome to the fourth edition of Adland, the magazine which explores what we can learn from the history of advertising about its present and future, taking in everything from Mascots to Mad Men, Typefaces to Television, Politics to Pandemics. It was produced by first-year students on the BA(Hons) Creative Advertising degree at Falmouth University.

Falmouth Advertising @falmouthadvertising on Instagram

Editor and Art Director Munro Black @m0b.adv on Instagram

Cover Luka Kolesnykova The Adland team Amelie Alcorn, Sissy Anderson, Amelia Belam, Munro Black, Eleri Blayney, Ellianna Braddick, Tara Brewster, Kai Brown, Koby Davies, Alice Deeks, George Denney, Issie Dexter, Gwendolen Franklin, Daisy Hawker, Abi Hinton, Hannah Hustwayte, Archie James, Courtney Jones, Luka Kolesnykova, Gracie Lawrence, Theo Martin, Ella McCa erty, Becca Mortimer, Harry Nash, Rose Perrin, Ivy Samuel, Kai Savage, Sam Shackleton, Rianna Storoszczuk, Kent Sturgis, Ed Talling, Rosie Whyte, Tilly Wilson

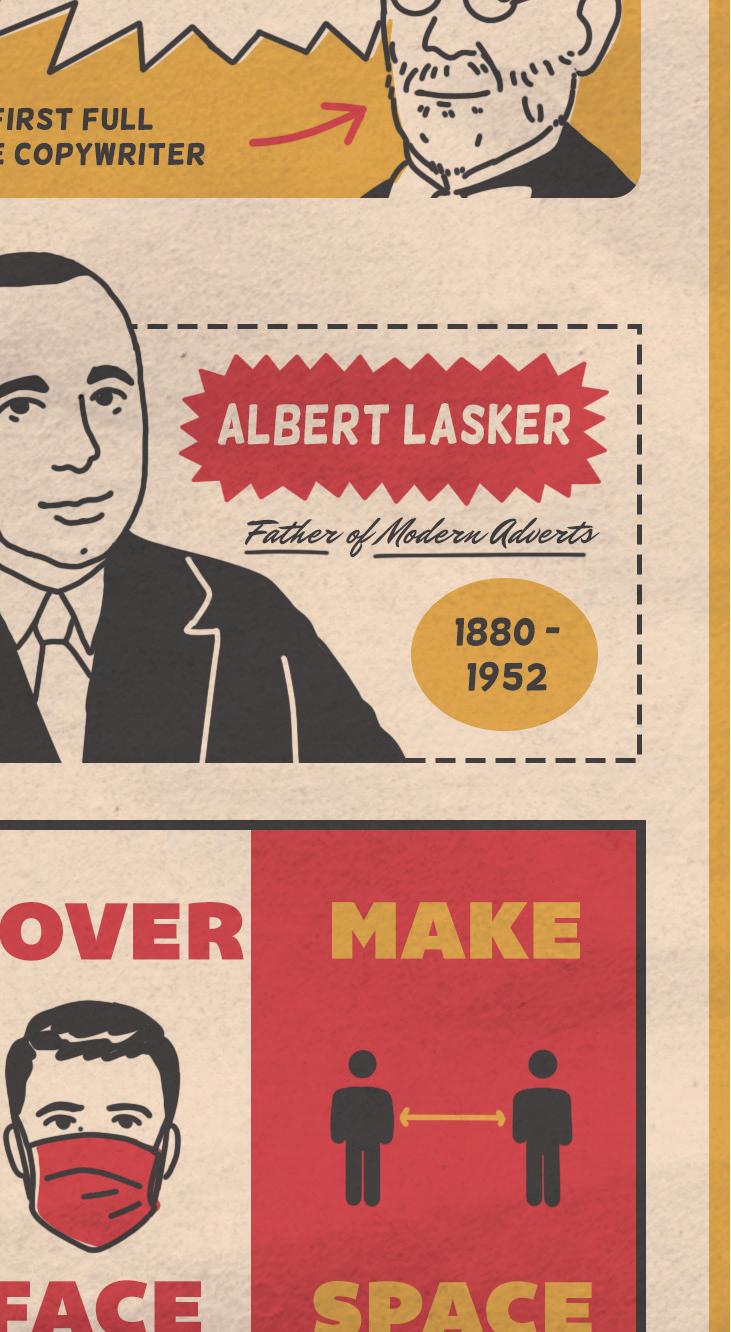

From ever-changing messages to three-pronged slogans, public service announcements have been hard to miss. But how should governments communicate in times of crisis? Ivy Samuel identifies some key takeaways from the UK’s response to the COVID-19 crisis

Back in the eighties, deep into the Thatcher years when rumours were spreading and panic was becoming endemic, the government of the day was facing a pandemic: HIV/AIDS, a virus that threatened death for anyone who caught it.

There are many ways to curb the spread of a virus. You’ve got the science: lockdowns, vaccines, developing treatments. And then you’ve got the communication strategy.

To tackle the rising Aids pandemic, 1987 saw the launch of one of the largest health campaigns this country has ever seen. The Don’t Die of Ignorance campaign, created by the agency TBWA, sought to raise awareness of the disease. In an article for The Guardian (2017), former designer Malcom Gaskin said: “It was like an alien plague.”

For people to protect themselves and those around them, they needed to get their facts straight. Consequently, the campaign took a deliberately dark and moody theme. The aim: scare people enough so they read the leaflets posted to every household, but so much as to cause widespread hysteria.

Prompting behaviour change is the main reason why any government bothers investing time and resources into creating a public information campaign. In the same way that commercial businesses try to persuade consumers to buy their products, governments try to persuade the public to follow their laws or advice on how to behave.

Fast forward to 2020. As the COVID-19 pandemic was beginning to take hold, we saw governments around the world using communication as a key tool in their arsenal.

Now, four years later, it’s important we look back at some of the British Government’s communication choices and reflect on those that worked and those that weren’t so effective.

On March 23, 2020, with the country gathered around TV screens, Prime Minister Boris Johnson

gave a widely anticipated announcement. The nation was entering lockdown. Johnson ended with the line: “Stay at home, protect our NHS, and save lives.” This became the main slogan used in the early days of the pandemic.

The Stay at Home, Save Lives campaign, as it was later shortened to, took a multifaceted approach. The adverts were featured on radio, digital, print and outof-home, all centred around the same message. It was a campaign that people were responsive to, according to the Cabinet Office, achieving an awareness rate of 92%.

Weiss and Tschirhart (1994) highlight the importance of delivering a trustworthy message that people are able to grasp: “Campaigns should deliver messages that are clear, credible, and easy to understand.” Regardless of how interested the public are in the issue, if it’s not communicated correctly its essence will be lost in translation. This became evident with the change in messaging that came later on.

As restrictions were beginning to ease and people were no longer required to stay at home, the previous government line was no longer relevant. So, a fresh slogan, “Stay alert, control the virus, save lives”, was

‘By trying to communicate nuanced changes to the rules succincinctly through the use of a line very similar to its predecessor, the government soon realised ‘Stay alert’ just didn’t have the same impact as ‘Stay at home’

rolled out. And with it came a barrage of confusion. Sixty-five per cent of the public were either “not very clear” or “not clear at all” on the government’s message, according to a YouGov poll.

By trying to communicate nuanced changes to the rules succinctly through the use of a line very similar to its predecessor, the government soon realised that “Stay alert” just didn’t have the same impact as the former “Stay at home”.

Despite the shift in message, a similar level of simplicity was expected from the public. People are willing to do the right thing but it’s up to governments to communicate in a way that is both digestible and easy to understand.

After a summer of “eating out to help out” and the virus beginning to feel further away, the country unfortunately saw a new wave in the pandemic. By September, shortly after the introduction of the

“rule of six”, where the public could only gather in groups of up to six, we were greeted with the launch of the Hands Face Space campaign created for the government by agency MullenLowe London.

In the TV advert we see people telling us why they wash their hands, why they wear a face covering and why they make space. It emphasised the importance of doing what you could to protect the ones around you, using a technique known as “triggering norms”.

Weiss and Tschirhart say that triggering norms is when a campaign aims to link individual behaviour to much wider social repercussions. It’s a strategy used by numerous public information campaigns around the world and has been a successful way to instigate behaviour change.

The Hands Face Space campaign attempted to make the pandemic, a global problem, feel personal. By mentioning family, friends and even co-workers, it allowed members of the public to visualise the potential impact their choices could have on those they care about, making it more likely it was something they would adhere to. As Weiss and Tschirhart put it: “Triggering norms can work as a strategy of influence, however, only if the norm that is evoked is powerful for the target audience and successfully connected with the target beliefs or behaviour.”

However, the slogan which accompanied the campaign was less effective. Despite the hashtag receiving a large amount of traction across social media, an Independent Sage report (2020) found that generally people viewed the messaging as vague. If you didn’t see the TV ad or the print campaign, the words

‘People were uncomfortable with this campaign as it felt like the government was using blatant guilt-tripping techniques to strongarm the public into changing their ways

“hands face space” in isolation, though memorable, simply had little meaning so wouldn’t lead to the desired changes in behaviour.

When we thought the pandemic might be behind us, and as 2020 came to a close, we found ourselves in another lockdown and saw the return of the familiar “Stay at home, protect the NHS, save lives” message but this time under the guise of a new campaign.

The Look Them in the Eyes initiative, also created by MullenLowe and released in January 2021, sought to adopt a whole new tone. This far more emotionally-charged approach included a video with real footage from Basingstoke and North Hampshire Hospital, featuring staff and patients. It aimed to confront people with the reality of their choices and forced them to take personal responsibility with the line: “Look them in the eyes and tell them you are doing all you can to stop the spread of COVID-19.”

It took making the pandemic “feel personal” to a whole new level. Journalists such as Rachel Cuncliffe in The New Statesman argued that it was in fact the government who should be taking the responsibility for failures in the pandemic and not ordinary people. This argument was reinforced by the Downing Street parties exposed later in the year.

People were uncomfortable with this campaign as it felt like the government was using blatant guilttripping techniques to strongarm the public into changing their ways. Though the use of emotion can be helpful in allowing a message to cut through, too much and a government seems desperate. This risks losing the public - an outcome you don’t want in the middle of a pandemic.

Whether the enemy is Aids, the Coronavirus or another health threat, effective public information campaigns are imperative. During a crisis, such as a worldwide pandemic, where people are filled with fear and misinformation spreads faster than the virus itself, the public looks to those in charge to inform the choices they make.

Guidance needs to be clear, messaging must feel personal, and above all trust is paramount. From Dominic Cummings’ eye-test at Barnard Castle to ‘partygate’, a lot of what dented the government’s own progress during the recent pandemic were

contradictions of its own making. If people don’t believe what they are being told is important, then why would they choose to obey?

As we look to the future, with all that we faced in the throes of COVID-19 now behind us, it might seem as though we’re out of the woods. But the risk of a new large-scale crisis that future governments will have to face is very real.

So, with this comes the hope that whoever is next can learn from what has come before and put together a communication strategy capable of steering the public in a crisis.

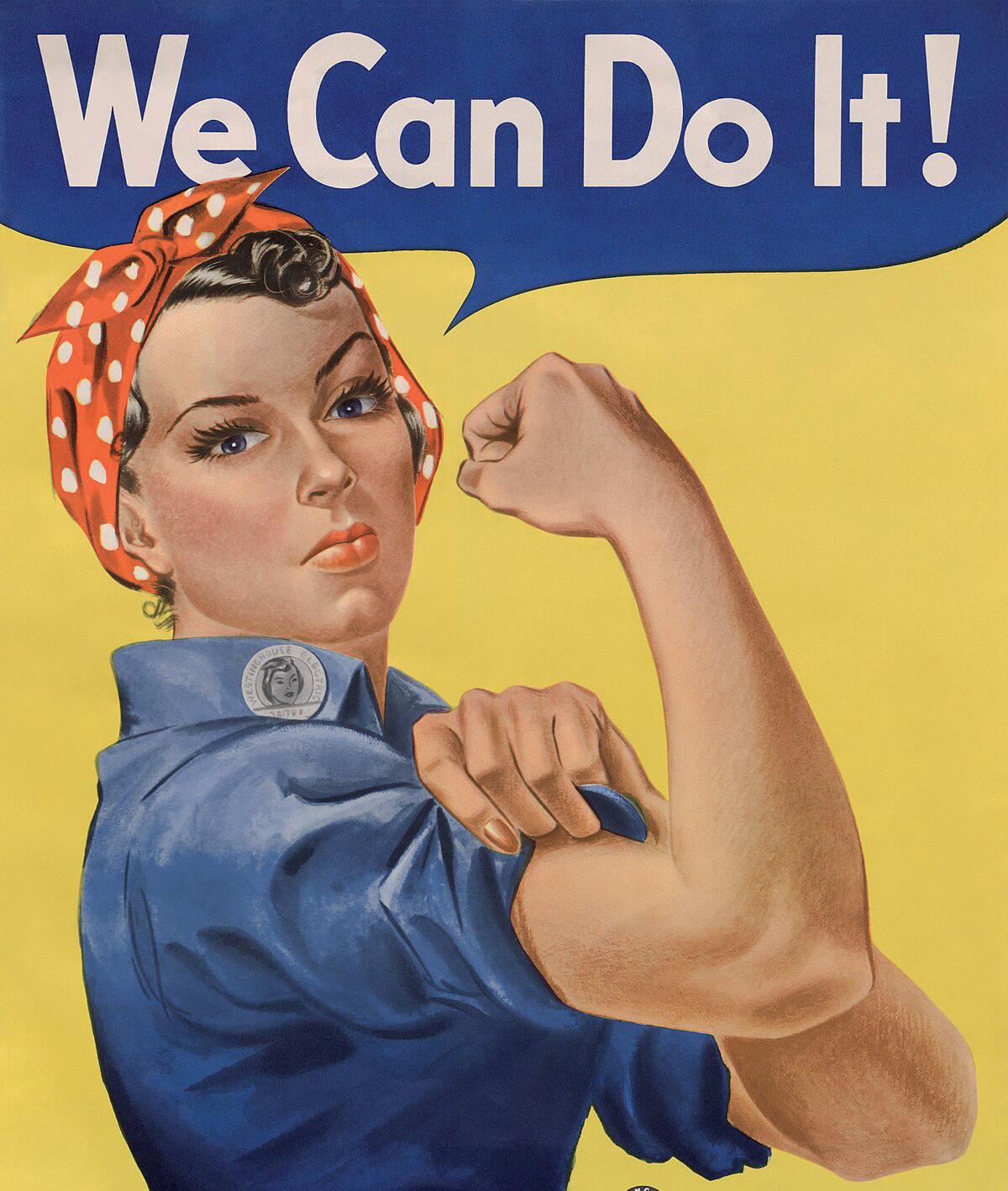

The Second World War was a transformative event in history, and it greatly impacted how advertising is today. Prior to the war, advertising relied heavily on newspapers and magazines. However, with the war on the horizon, the entire advertising landscape changed. The world saw a new form of advertising that used propaganda to appeal to emotions rather than being fact-based. As we continue to develop modern-day advertising, we can look back to the pre-war era, the use of propaganda, and product advertising from the wars to learn how effective advertisements should appeal to audiences. This article will delve into these aspects of WWII advertising, examining how they are still relevant to modern advertising.

Before the war, print media was the primary method of advertising, and ads were typically text-heavy with little imagery. According to The Outlook newspaper from the early 20th century: “Ads should be written so that they will appear to be news items rather than advertising.” Advertisements were meant to blend in with the news rather than stand out.

Advertising was focused on presenting the unique selling proposition (USP) of a product to consumers, rather than using attention-grabbing tactics. Advertisements were not seen how they are today, as a form of entertainment or art, but principally as a way to convey information about a product or service to the consumer.

During World War II, advertising played a key role in the UK’s propaganda efforts. Adverts were used as a tool to rally support, boost morale, and promote a sense of unity and purpose among the people of Britain. Campaigns encouraged the purchase of war bonds and emphasised the importance of rationing and conservation. The Lord Kitchener Wants You campaign, for example, urged people to sign up for the war and was a notorious recruitment tactic. As the war progressed, advertising became increasingly sophisticated and targeted.

Among its many challenges, World War II required innovative solutions to keep spirits high and the economy afloat, including the development of many advertising techniques that we still use today, writes Abi Hinton

Government propaganda also involved the use of cartoons, such as Pip, Squeak and Wilfred, which featured anthropomorphic animals who served as symbols of British fortitude and unity. The characters appeared in various forms of media, including comic strips, toys, and even in advertising for products such as cigarettes and chocolate. This was the start

Some key takeaways from propaganda advertising would be the use of fear and repetition. Fear can be seen in campaigns on health or political issues

of more sophisticated targeted advertising. What’s more, for the first time in advertising history, radio and television were used extensively. In the USA, as Cynthia Meyers wrote in A Word from our Sponsor: “The advertising industry and commercial radio became closely associated with the federal war effort. Despite the war economy, both industries grew and thrived.”

Some key takeaways from propaganda advertising would be the use of fear and repetition. Fear can be seen in campaigns that are trying to raise awareness for certain diseases or political issues such as the

posters by Cancer Research UK which explain how to stop early signs of the disease.

Repetition is used a lot in modern-day advertising to help drill in the brand’s message, like when NIKE released their Just Do It campaign in 1988 which was made by the Wieden+Kennedy agency. The slogan was plastered onto every advert they created and was so successful it is still being used over 30 years later.

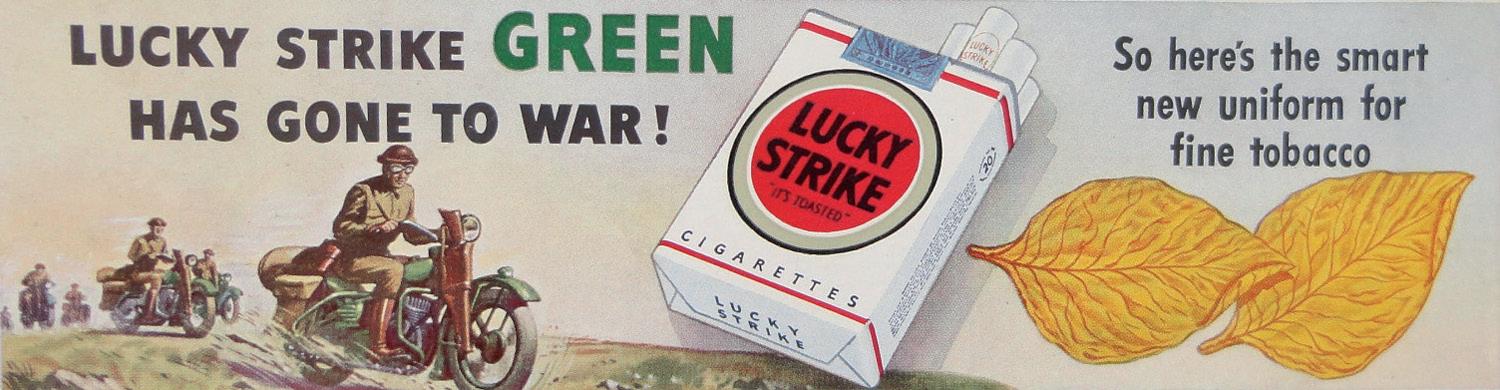

According to a report published by the American Cancer Society, during World War II the tobacco industry spent approximately $130 million on advertising. This included adverts in newspapers and magazines, as well as posters and other formats made to be sent overseas.

One of the most iconic cigarette advertising campaigns of the war was for the brand Lucky Strike. The brand was heavily marketed to soldiers, with slogans such as “Lucky Strike Green has gone to war”. These ads emphasised the idea that smoking was a way for soldiers to relax and relieve stress and that Lucky Strike was the best brand for the job. In modern times, promoting smoking is heavily restricted but the legacy of cigarette advertising during World War II has become a reminder of the power that advertising holds in influencing our attitudes and behaviours. Moreover, it can teach us how the ever-changing supply and demand of products can impact the production of campaigns and marketing as a whole.

After the war, the supply and demand changed dramatically as factories had been mass-producing military supplies and other war-related products for over four years. Now, there was a surplus of these items. Manufacturers had to think of a new way to entice domestic buyers into purchasing more products so they teamed up with psychology experts to gain some key insights.

They found that subconscious decisions were more effective than conscious ones and from Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, they realised that humans have a large need for feeling respected and confident. This was a key turning point in the history of advertising as these experts realised they needed to switch to more visual and emotion-based selling.

People have since researched into colour theory and further into human psychology which is why you

see so many examples of emotion-based marketing in modern-day advertising. An example of this is an advert for Apple’s iMac in 1998 with the slogan “Chic not geek”, drilling into people’s subconscious that you would be cool if you owned their product, further exploiting that innate human need to be accepted.

So the Second World War created a huge shift in the way adverts are created. From propaganda to using psychological strategies, we can still apply all of these techniques to adverts and campaigns today. The power of marketing and advertising to shape public opinion and behaviour is still as important today as it was during World War II. Just because there isn’t a world war happening right now doesn’t mean fear tactics and propaganda don’t exist. Advertising would not be the way it is today if it

wasn’t for all those companies stepping up and trying to engage the public into doing their bit for their countries.

In the years that followed the war, advertisers adopted many of these techniques and shifted their focus from promoting products to promoting brands. The rise of technology has further changed the way that advertisers reach consumers, with new tools such as social media, virtual reality, and artificial intelligence transforming the advertising landscape.

As we look to the future, it is clear that advertising will continue to evolve and adapt to new technologies and consumer behaviours. However, the lessons learned from the propaganda campaigns of WWII will continue to inform and inspire the world of advertising for years to come.

‘

Just because there isn’t a world war happening right now doesn’t mean fear tactics and propaganda don’t exist. Advertising would not be the way it is today if it wasn’t for all those companies stepping up and trying to engage the public

The tobacco advertisement industry was one of the largest sectors in the 20th century. But then governments began to put public health before private profit. Kent Sturgis reflects on the rise and fall of the cigarette giants

During the tobacco industry’s long reign, there were many concerning ways that they promoted their products to the masses. In the 1940s, it was not uncommon to find the words “Just what the doctor ordered” plastered across a packet of cigarettes. Companies would hire doctors and dentists to recommend their products to reduce the major health concerns that surrounded the use of tobacco.

“More doctors smoke Camels” was a slogan used by Camel Tobacco to mislead the population and steer them towards smoking, and to show that cigarettes were, if anything, good for them.

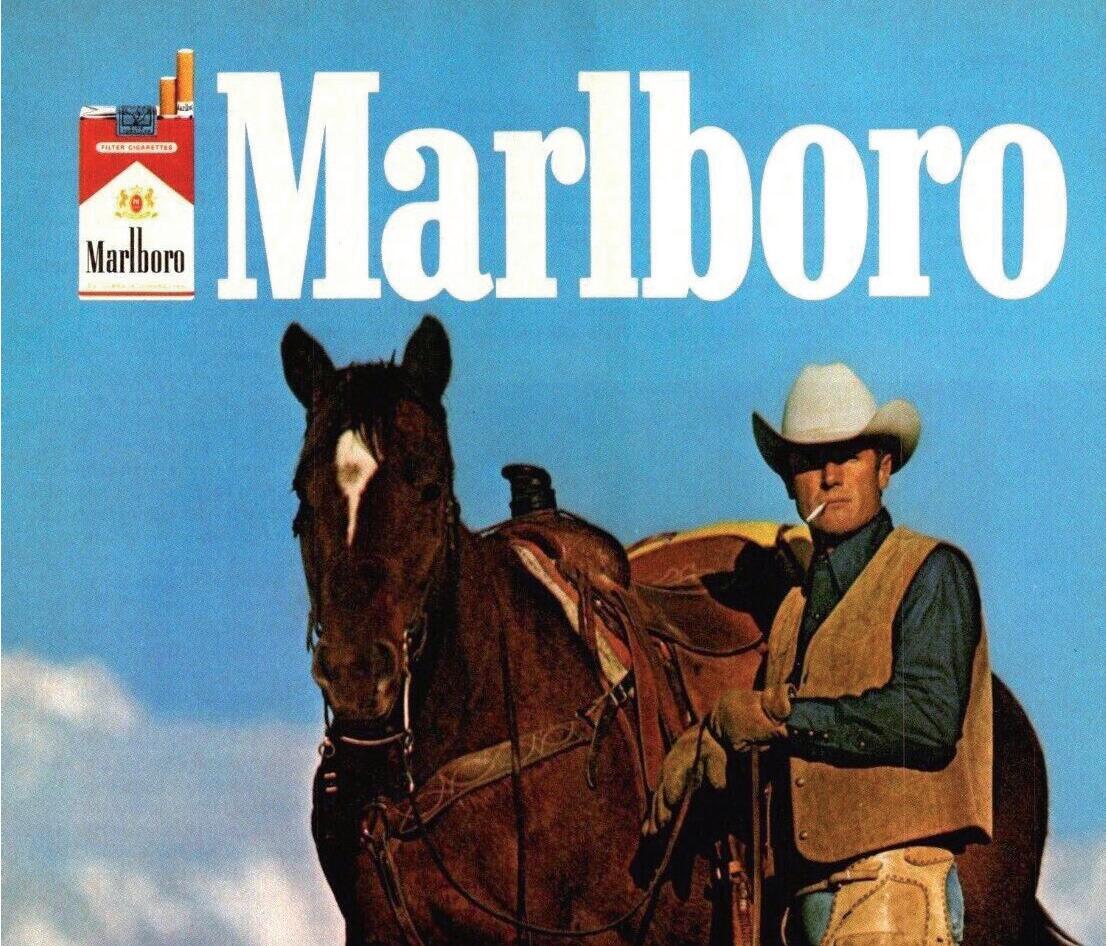

This radical method of promoting a product with negative side effects was built on in the late ’50s and ’60s with celebrity endorsement. Tobacco advertisements appeared regularly in television and at the cinema, with celebrities fronting their campaigns

to recommend their products to fans. This period gave birth to icons like the Marlboro Man, a rugged cowboy from Texas depicted on horseback covered in dust, smoking a Marlboro cigarette. Although unconventional for the farmer lifestyle (which was in favour of chewing tobacco) he arguably became one of the most successful campaign characters in history, selling the ‘spirit of the cowboy’ to the American nation, along with many many packets of fags.

Within a year of the Marlboro Man’s debut, the company went from holding only one per cent market share to being the fourth bestselling brand of tobacco in the USA, with sales today of over $23 billion. Before the icon was created, the company’s product was seen as feminine and considered a ‘woman’s cigarette’. It wasn’t until the introduction of the macho cowboy in the 60’s that the brand underwent a “sex change”, according to Stanford studies. Part of Marlboro’s campaign was to convince the male audience that filtered tobacco was no less masculine. Part of Marlboro’s campaign was to convince the male audience that filtered tobacco was no less masculine.

Within a year of the Marlboro Man’s debut, the company went from holding only 1% market share to being the fourth bestselling brand of tobacco

This clearly demonstrates how one campaign can completely rebrand a company in the eyes of the public.

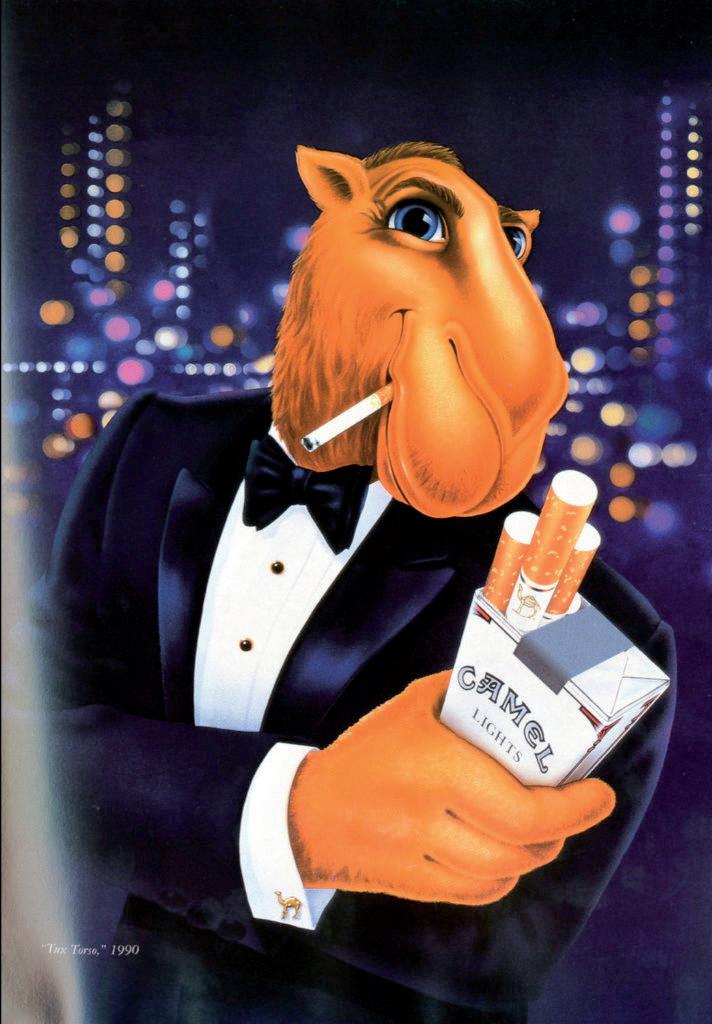

This use of celebrities in advertisements was followed by a more daring strategy, with kid-friendly characters littering the tobacco ads. In the 1990s cartoon characters were introduced such as Joe the Camel. This was a character created by R.J. Reynolds, the second-largest US cigarette manufacturer. First stepping into the world of icons in December 1991, his introduction caused the Camel brand market amongst teens to grow from 0.5 per cent to a staggering 33 per cent within three years. His cool style with leather jackets, motorbikes and attention from females was enough to dazzle the young audience and bring him to stardom.

Questions had always been raised around the ethics and legality of the advertisement and promotion of tobacco-based products, due to the health risks

and influence many advertisements had on children. Towards the end of the 20th century cigarette brands in the UK found themselves working against increasingly strict advertising restrictions.

Some of the earliest government-implemented legislation came in 1965 in the form of the Television Act which restricted the advertisement of cigarettes on television. Other laws around this period restricted people from being shown in tobacco advertisements as it could suggest enjoyment, and healthy environments couldn’t be implied.

However, this did not see the end of all cigarette advertisements. Benson & Hedges created a series of surrealist billboard adverts inspired by painter René Magritte. The campaign was utterly random; the

images individually were nonsense. They were just aesthetic pictures with a pack of Benson & Hedges cigarettes situated in the frame, meaning the ASA couldn’t reject the advert. It was in this campaign that the iconic pyramid advert was born. It was so successful that a cinema ad was commissioned, which was just as bizarre. It was known as ‘The Swimming Pool’. Again, the advert had no real story or logic,

consisting of rattlesnakes, helicopters, a swimming pool and an oversized pack of cigarettes with a canopener. The elements, although confusing, worked together and were attention-grabbing and memorable.

The visual campaign shot in the Arizona heat was wonderful and is frequently hailed as being one of the most revolutionary and inspired campaigns that have ever been produced. The creatives behind it had been forced to change their strategy and thinking, and from this adversity emerged some memorable and effective ideas.

Further limits were imposed on the advertisement of tobacco in 1990. The Broadcasting Act was passed which restricted the advertisement of loose tobacco on TV and all tobacco products on the radio. This heavily affected the advertisement markets, as in the prior year the tobacco industry had spent $4.6 billion on advertisement, or more than $12.6 million a day. It was this legislation that saw the end of icons such as Joe the Camel. However, this did not herald the end of all cigarette advertisements. Some of the

most recognisable and iconic adverts were created during this period of heavy restrictions and political arguments. Many ad agencies began to explore the surrealist style pioneered by Benson & Hedges. One of the most recognisable of these was done by Saatchi and Saatchi for Silk Cut. The campaign was as simple. It featured ‘silk’ that had been ‘cut’. The campaign not only mirrored the brand’s name but attracted the target audience using expensive and sophisticated silk material. The striking and innovative series of ads was so successful that even now the shade of purple they used for the material is still associated with the Silk Cut brand.

The advertisement of tobacco was unarguably still very effective up to the very end of the 20th century. However, by 2009 it had almost disappeared completely, after a new onslaught from lawmakers. The first was the Tobacco Advertisement and Promotion Act of 2002. This finally banned the press and billboard advertisement of all tobacco products, as well as direct marketing.

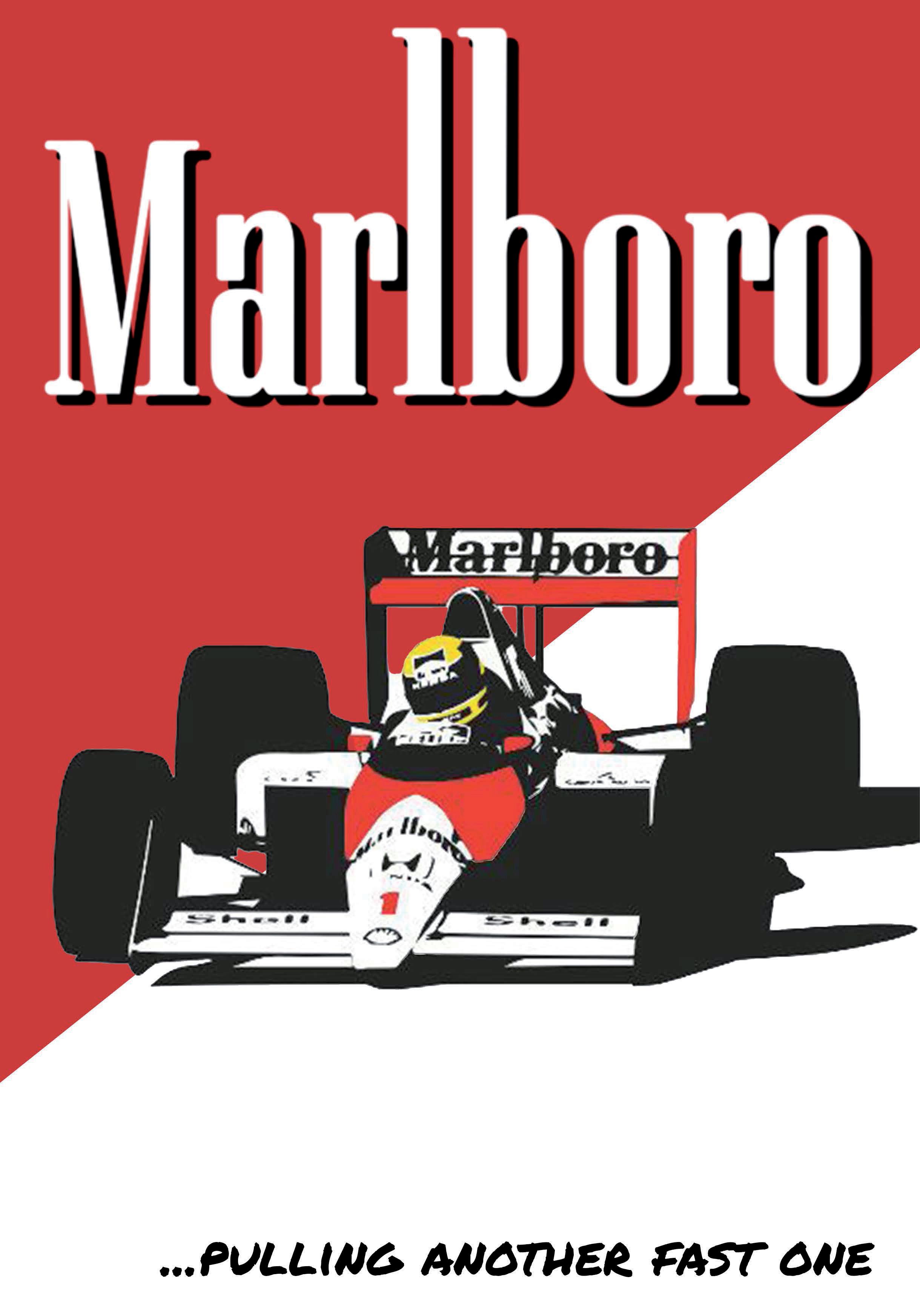

However, there were always going to be loopholes. Tobacco companies had a strong hold on the sponsorships of many televised sporting events to subconsciously associate their products with healthy and active lifestyles. Companies used sports like Formula 1 to connect with the glamour the sport thrived on and its drivers. Tobacco advertisement in Formula 1 races dates back to 1968 when Gold Leaf cigarettes became the first ever sponsor of a team in F1, sponsoring team Lotus and decorating their cars in red white and gold, the colours of the tobacco brand.

Tobacco brands were seen on almost every car racing in F1 with teams profiting from the sponsorship of a tobacco company. Marlboro proudly sponsored McLaren for over 20 yearsfrom 1980. This loophole was shut in 2005 with a second Tobacco Advertising and Promotion Act banning sponsorship in all sporting events. As expected, tobacco companies did their best to bypass the law. Marlboro logos were still used on Ferrari cars in races outside Europe, for example.

However, these attempts were short-lived. The relationship between many F1 teams and tobacco companies has surprisingly not been destroyed despite Marlboro still paying $100 million per year for the sponsorship of Ferrari cars. In countries that still allow advertisement images on tobacco packets it is not uncommon to find a Ferrari Formula 1 car situated beneath the name Marlboro.

Mass media cigarette advertising is undoubtedly a thing of the past in many countries, including the UK. However, the innovation and creativity that was put into this sector of advertising do not need to go to waste as much can be learnt about the adverts made in the face of strict legislation and implemented in other sectors. It is even possible that one day, anti-smoking ads will be created by health organisations globally that may use inspiration from adverts like the B&H Swimming Pool or Silk Cuts campaigns. In addition, other sectors may soon have to adapt their own selling strategies in the face of fresh restrictions.

Products like sugar and vapes with high health risks are likely to be affected and may have to turn to more surreal or bizarre ways of advertising. Campaigns that promote gambling will most likely be targeted by legislation to prevent the promotion of gambling to a younger audience, like that of tobacco in the 1980s.

The tobacco industry was not the first to work under large legal restrictions and most definitely won’t be the last. But currently, it is the most famous, and has created some of the most memorable adverts in creative advertising history.

Some of the biggest and best adverts aren’t trying to sell you car insurance or promote a chilled carbonated beverage. They’re altering human behaviour and raising awareness of issues. But what do governments and advertisers have in common? Ed Talling offers some answers (overleaf...)

In the UK, HM government dominated the top ten of UK advertisers in 2020 after splurging £164m in its ad department, surpassing Unilever and Sky in the process (Glenday, 2021). But why does the government advertise at all?

The government has different aims from regular advertisers: it wants to initiate positive behaviour, reduce negative behaviour, encourage law-abiding behaviour or recruit for tough service jobs (Lannon, 2008).

At first glance you may think these targets are simple but altering human behaviour and societal beliefs is very tricky. “The public service challenge is often one of creating new behaviours rather than displacing a brand one normally buys… changing habits requires a strategy that confronts, and challenges entrenched attitudes.”

‘Their direct, plain and colloquial style made the posters easy to understand and instantly recognisable, aiding their effectiveness in recruiting men to fight for Britain

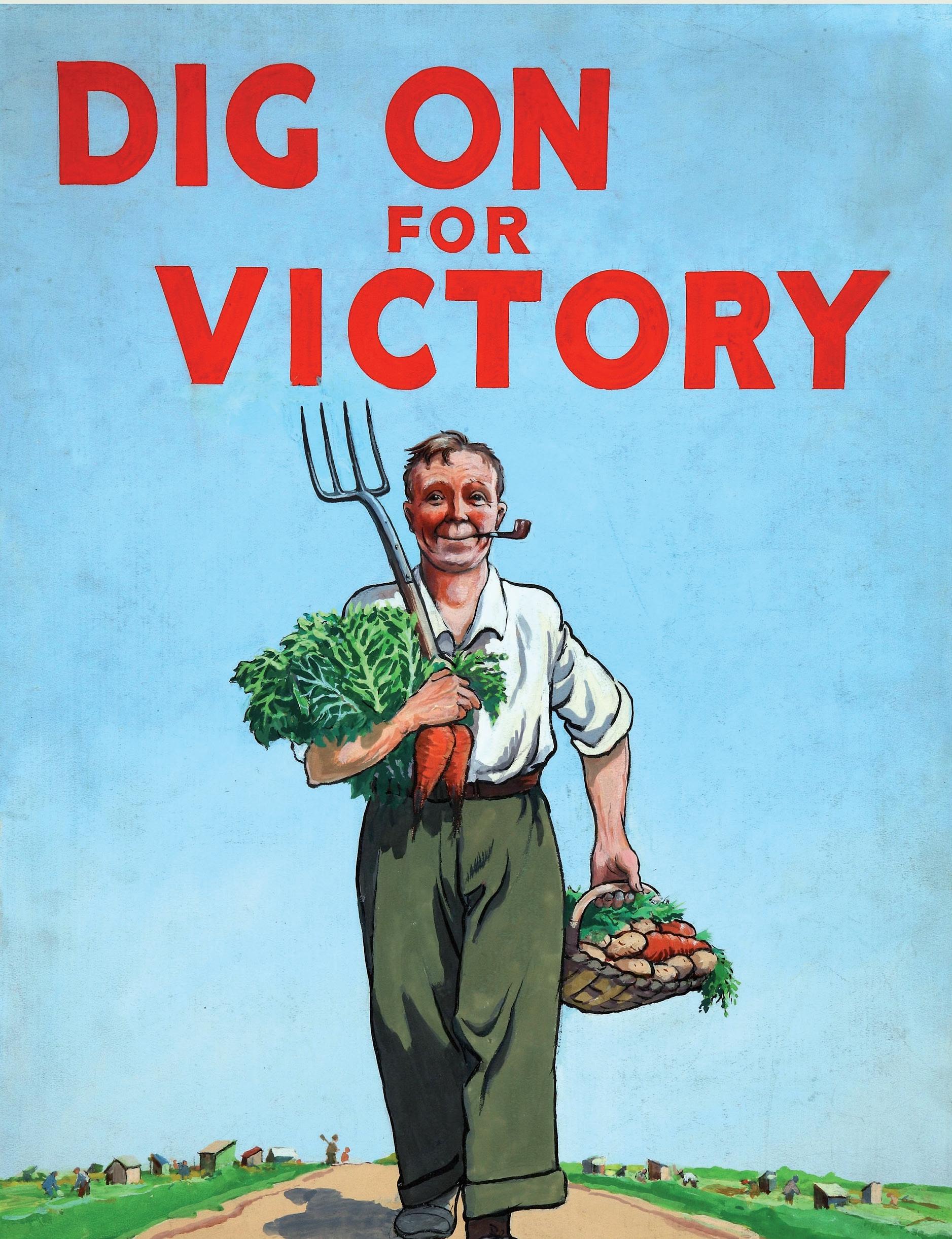

Despite the tragedy of World War One, it paved a new way for governments to speak to the public. Led by the Minister of War, Lord Kitchener, the Wants You posters were produced from 1914, and became a significant recruitment technique for the nation’s army. It depicted Lord Kitchener pointing out to the reader, calling on men to “join your country’s army” in bold, sans serif type; guilt tripping the reader into taking action for the good of the country. Other campaigns during wartime Britain included ‘Dig for Victory’ which encouraged civilians to grow their own fruit and vegetables due to food rationing and ‘Careless Talk Costs Lives’ which warned people to be mindful of not talking too freely as the enemy may be listening. Their direct, plain, and colloquial style made the posters easy to understand and instantly recognisable, aiding their effectiveness in recruiting men to fight for Britain.

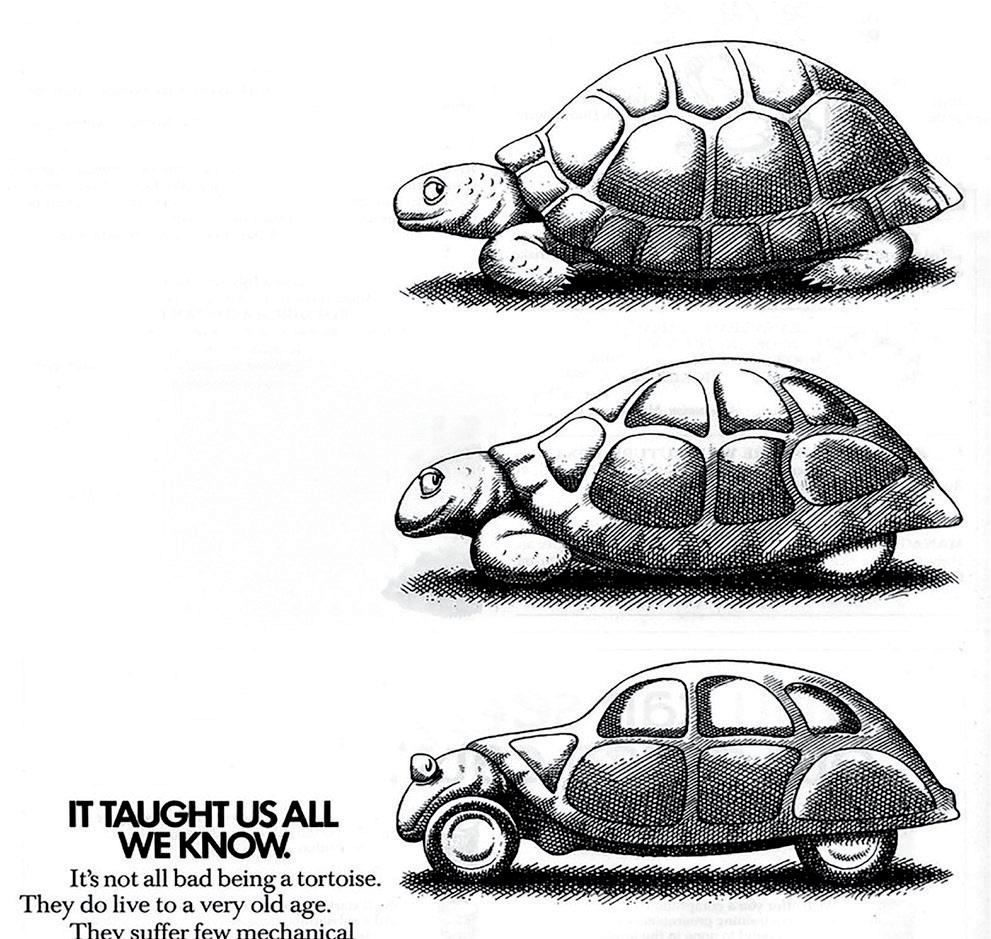

These techniques matter in advertising as sometimes simplicity is the key to a successful campaign, evident in Citroën’s posters for the 2CV. Citroën subverted typical features of car adverts, instead of selling the amazing new features and luxury touches. Its advert series admitted how the 2CV is small, slow and has very few creature comforts such as not having cruise control, remote-control door mirrors, a rev counter or cigarette lighter. But these didn’t matter to the average consumer. Instead, they focused on the points that really mattered such as easy manoeuvrability, superb reliability and all-round visibility - as well as the low price. These simple yet sophisticated adverts helped aid the production of 5,114,969 units between 1949 and 1990 (Stellantis, 2023).

Moving through the 20th century we saw a growth in the topics covered by governments, becoming more varied in their messaging and increasing the scope of target audiences. Road safety adverts are a good example. These often featured more shocking graphic images such as people flying through car windscreens covered in blood as a result of not wearing their seatbelt or hitting a child due to the effects of alcohol on people’s driving abilities.

In 2014, Northern Ireland’s Department of Environment produced an advert which showed a car losing control on the road, flying through a wall, and rolling over a group of young schoolchildren, killing them instantly. This advert was banned from

appearing pre-watershed as many complaints were raised over its gruesome and vile imagery. This and many other adverts would have stood out to the audience, as up until then, many road safety adverts were aimed towards children to be safe and caution when on or near roads, evident in the Tufty the Squirrel which was conceived by Elsie Mills MBE in 1953 to introduce road safety message you kids (ROSPA, 2024). These new but occasionally graphic ways of showing the very real impacts of unsafe driving may have been more impactful as the viewer can see what could happen to them, from injury to death of themselves or others. These somewhat emotionally-challenging campaigns show how there is sometimes a need for more intensive forms of advertising.

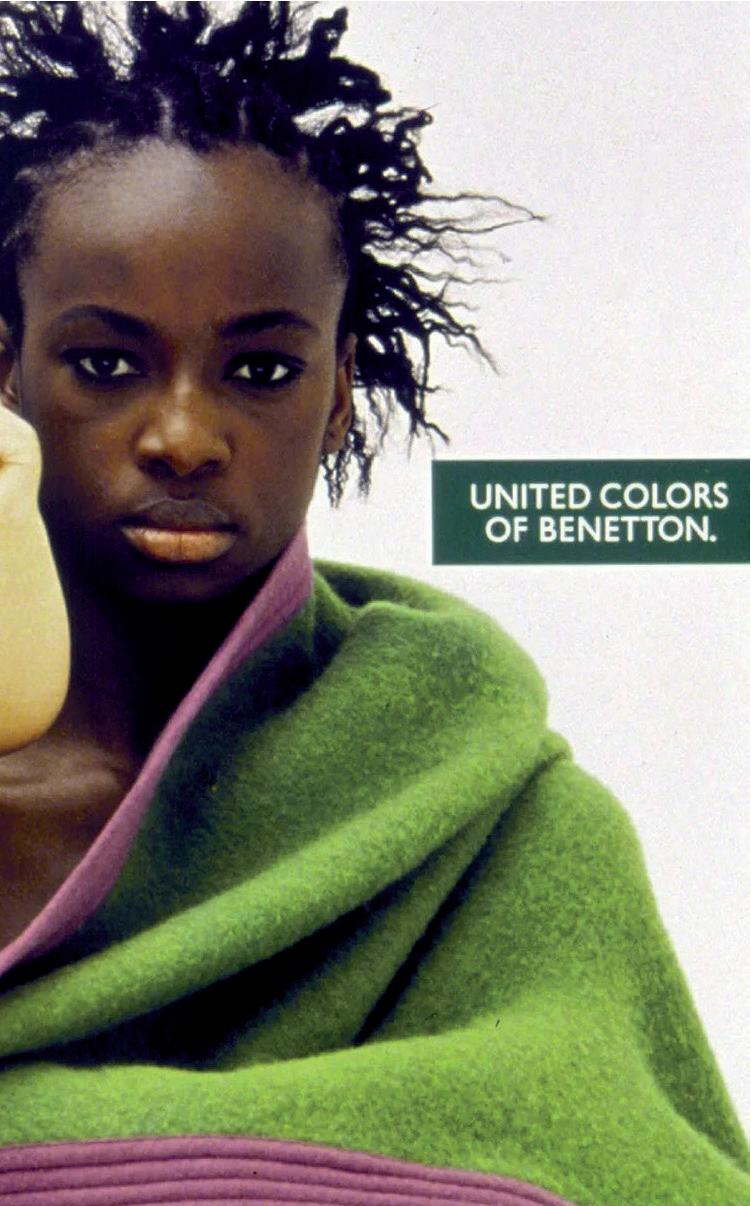

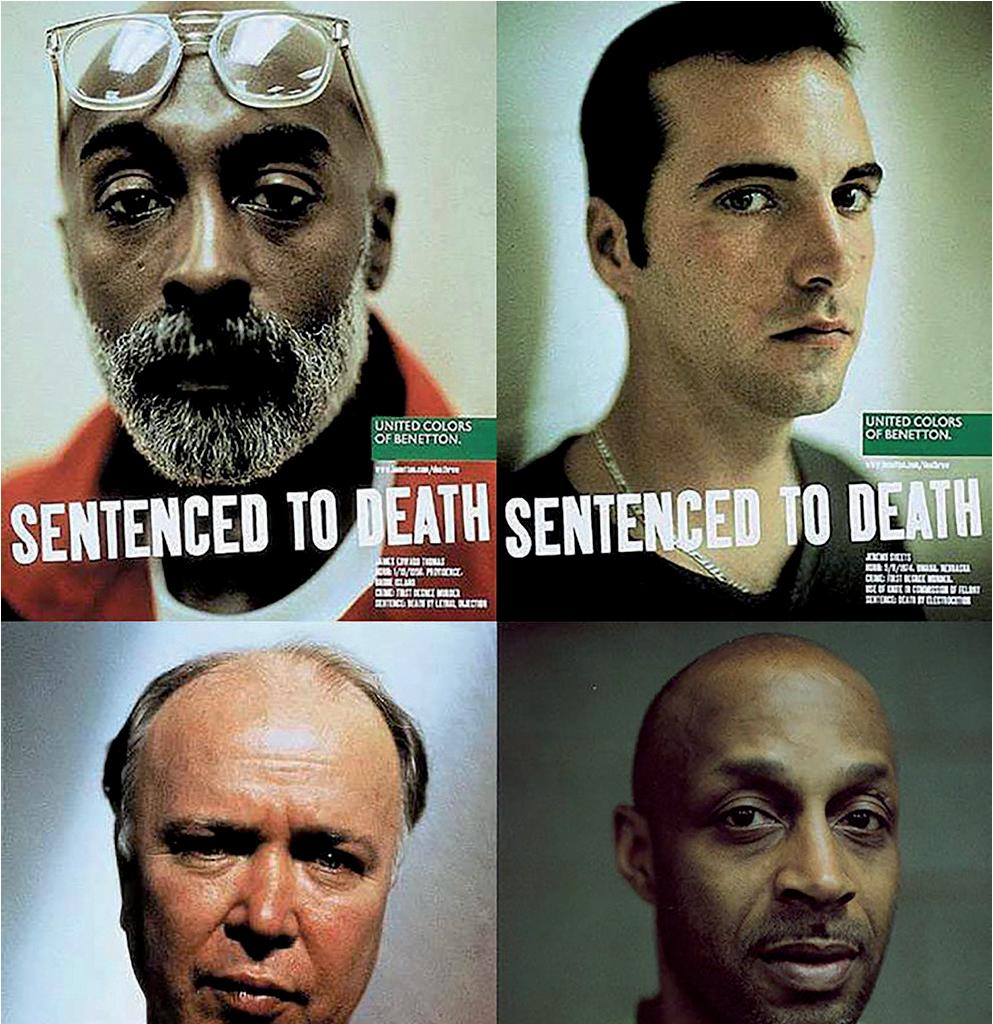

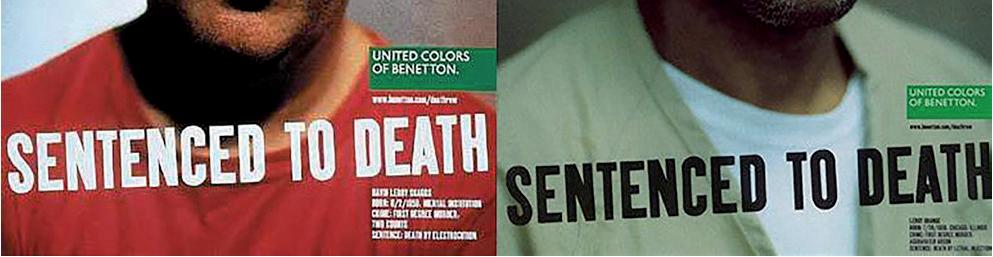

Benetton, a global fashion brand, could have picked up on this; but may not have succeeded with the

execution quite as well as the government did, evident in its ‘United by Colours’ campaign during the 1990s. These contained controversial images to essentially increase profit. Featured were an interracial, homosexual family; an AIDS patient on his death bed; multicoloured condoms; an army uniform covered in blood, world leaders kissing and death row inmates (Eilidh Nuala Duffy, 2017). All these images relate to a topical news story or societal beliefs, when emotions surrounding such subjects would be very sensitive and raw. Many of these adverts received major backlash and negative comments. Nonetheless, the campaigns were impactful, gaining traction and using shock tactics will have impacts for the audience, whether for good reasons or bad.

Governments need to be very aware of who they are targeting when developing a new campaign; if done wrong it can result in a lack of interest from the

viewer and reduce the effectiveness of the message. Having a clear audience in mind is apparent in the Smokefree campaigns regarding tobacco. These adverts highlight the dangers that smoking has for your health but also others around you. The obvious target audience are smokers, which is fairly broad as many people of all demographics smoke, but often the audience is narrowed down even further, as seen in the UK Health Security Agency advert from 2013, targeting smoking parents who have young children.

This highlighted how much of the smoke from cigarettes is invisible, and no matter how safe you try to be, your children will still be impacted by your smoking. The aim was to encourage parents to be more careful when smoking near their children or give up smoking entirely as they wouldn’t want to do anything that could cause harm to their children. For context, cigarette and tobacco advertising in the UK was seriously restricted in 1965 and banned in the press, on billboards and via direct marketing in 2003. Tobacco companies were banned from sponsoring Formula 1 teams and sporting events in 2006 and the sale of cigarettes from vending machines and the adverts appearing on them was prohibited in 2011 (Ash, 2019). After decades of smoking-related adverts, the government needed to identify the exact audience to target.

Marmite also has a very distinctive audience in mind, which gave birth to their slogan: “You either loveit or hate it.” Much of their advertising targets people that fear or dislike their product. The Marmite Neglect advert plays on how some people may buy the product but never use it as they end up hating it and banishing it to the back of the cupboard. By contrasting the distinct divide between the lovers and haters of Marmite, it highlights how they are very aware of their audience, whether it be for good reasons or bad, but also has helped generate a memelike culture surrounding their product.

We can see how, over the past 100 years, the government has altered its techniques to convey different messages to various audiences. This may be due to changing trends, different demographics, or maybe people just aren’t listening to regular adverts

and creatives need to produce something new and impactful. Simplicity, new communication strategies and audience awareness are all key parts of advertising but can carry huge risk factors when used by the government; if an advert fails in its aims it can lead to an incredible disconnect to its population.

“Advertising is the art of convincing people to spend money they don’t have for something they don’t need,” according to Will Rogers, cited in Advertising and Society by Carol Pardun. Advertisers can learn a great deal from how the government uses their advertising resources and techniques to help deliver impactful and meaningful adverts with depth as seen with Citroën, Benneton, and Marmite.

‘We can see how the government has altered its techniques to convey different messages to various audiences. This may be due to changing trends, different demographics, or maybe people just aren’t listening to regular adverts

Being gay was not legalised until the 1960s (Burston, 2017). For centuries, queer people have found subtle ways of sharing their identities without catching the attention of an unaccepting society (Fanucci, 2023). Due to this, many ads showcasing queer identities were coded. Advertising has been one of the main communication tools throughout history and could be subtly used to communicate with minorities, like LGBTQ+ people. Looking back at certain ads, it’s clear that they were winking at queer people. It was a lovely form of secret activism that was not obvious to the heterosexual eye.

For example, the All-American Man (Fast Company, 2023) was an ultra-masculine man stereotyped in most early 1900s advertisements. You know him: he’s preppy, broad-chested and plays golf. He was created by gay illustrator and advertising genius J.C. Leyendecker. Leyendecker painted the figure to sell everything from cigarettes to socks to underwear to razors. He was a household name that held the standard for the modern-day man and brought homoeroticism to the masses. His works featured a lot of men glancing at each other, usually in intimate conversation or exchanging lustfully charged looks. Sometimes, the figures were holding sexually suggestive items like golf clubs or canes. One of Leyendecker’s popular works that showcases this is the And it floats! campaign for P&G (99-44/100% Pure… It Floats, 1882), mostly featuring men bathing with homoerotic connotations in its copy and imagery.

The first endeavours corporations made to attract queer consumers followed the 1969 Stonewall uprising and the first Pride march in 1970. These events shifted the visibility of LGBTQ+ people and the nascent stages of the modern gay rights movement. However, catering to queer customers still posed a risk in the early 1980s as LGBTQ+ individuals were highly discriminated against due to the AIDS epidemic. Even though there was a shortage of insights into LGBTQ+ people’s tastes and spending habits, there were a few advertising trailblazers that successfully targeted queer consumers and help catalyze the confirmation of their existence in society.

Due to LGBTQ+ individuals’ presence in bars and nightclubs, alcohol companies were one of the first to target queer consumers.

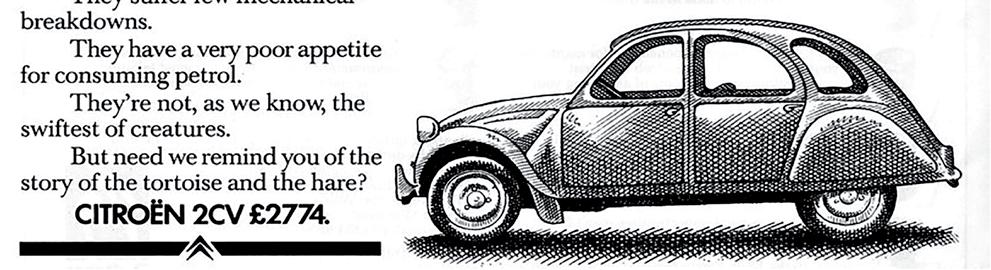

Absolut Vodka’s creative Michael Roux committed as early as 1981 to court gay and lesbian consumers, believing they were trendsetters (The New York Times, 2019). Keeping a close eye on the community has bred a lot of inspiration for Absolut; creating their famous ad with Andy Warhol, a wellknown queer artist who skyrocketed Absolut’s’ image (Absolut Warhol, 1988).

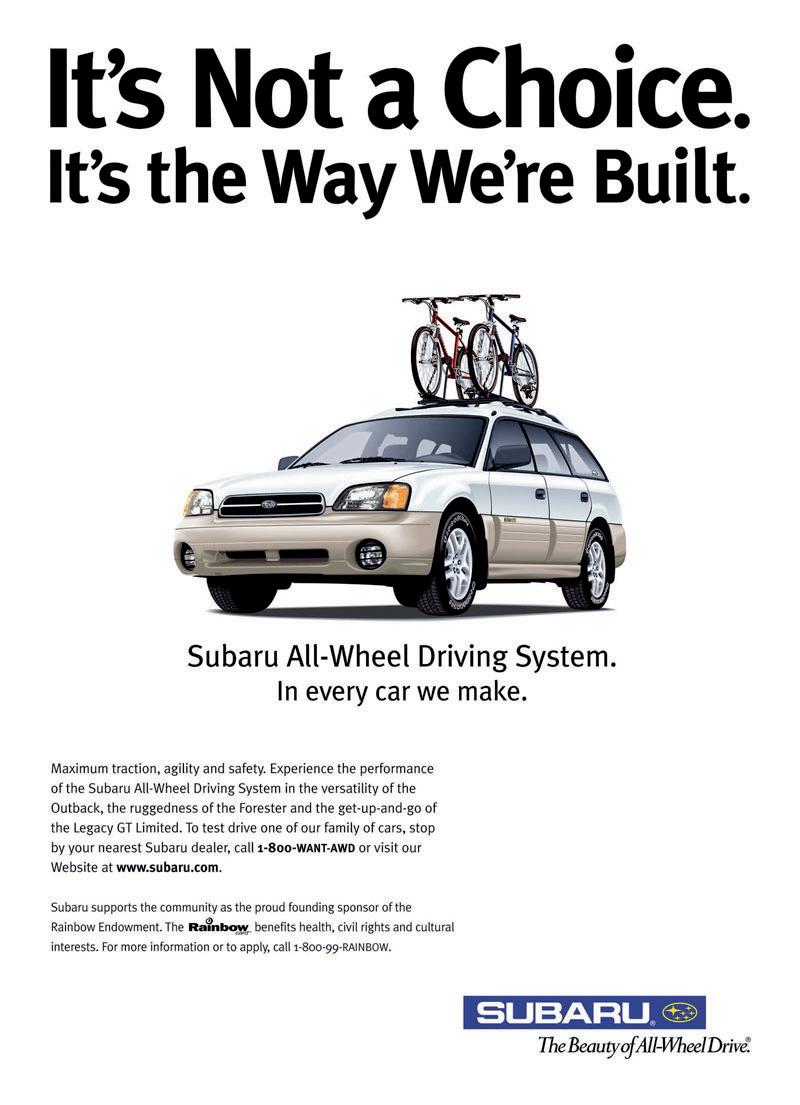

“Gay vague” is a term that describes the desire to target queer consumers while avoiding public blowback. A series of print ads by the Japanese car company Subaru illustrates this well. It leaned into its queer customer base after research showed that

The first ad to showcase a queer couple resulted in a bomb threat. Today, inclusive ads have gone from revolutionary to middle-of-the-road and back to controversial again.

Amelia Belam dives into the history of LGBTQ+ ads

lesbians were their ideal target audience. Lesbians liked Subaru’s dependability and size, and were four times more likely than the average consumer to buy a Subaru (Priceonomics, 2016). Their mid-90s vaguely gay ads consisted of taglines with double meanings such as “Get Out. And Stay Out” which could refer to

either exploring the outdoors in a Subaru - or coming out as gay.

Another typical “gay vague” commercial was from Volkswagen. It aired around the same time as the coming-out episode of the TV show Ellen in 1997, a pivotal gay moment. The ad featured two men

driving in a neighbourhood and salvaging a discarded armchair. Volkswagen didn’t intend the ad to depict a gay couple but Michael Wilke, founder of AdRespect, said that “they didn’t mind if people read it that way”, adding: “That was a real switch for advertisers.”

The first openly gay ad was IKEA’s 1994 Dining Room Table, a TV commercial made by the Deutsch Inc. advertising agency. It aired on local television stations in NYC, Philadelphia and Washington DC at night. The ad centres around Steve and Mitch, a gay couple in search of a dining room table. It cuts between the couple searching the IKEA store, joking about each other’s taste and sharing some anecdotal moments of their relationship. It’s sweet and comical, and they feel like an authentic couple.

Companies began to go after the market as research on queer populations and their spending grew

The ad was subject to a significant backlash. It caused protests by conservative and Catholic groups expressing their outrage. Some IKEA stores on the west coast of the USA had their phone lines inundated by protesters expressing their anger at the announcement. The most intense reaction was a bomb threat which caused an IKEA store in Hicksville, NY, to have to evacuate its staff and customers.

Fast forward to the late 1990s and LGBTQ+ individuals were gaining more rights. Companies began to go after the market as research on queer populations and their spending grew. Political events such as President Bill Clinton declaring June as “Gay and Lesbian Pride Month” in 1999, the corporate Equality Index (policies to create a safer workplace for LGBTQ+) in 2002 and Massachusetts becoming the first to legalise same-sex marriage in 2003, aided a new era of queer marketing.

Corporations such as Nike, Boeing and Microsoft expressed their approval for same-sex marriage and Pride celebrations began attracting sponsorships. Due to this, LGBTQ+ representation began showing up; for example, an ad in 2013 for Amazon’s

Kindle Paperwhite, was among the first to use the word“husband” rather than “boyfriend” about a gay couple.

In recent years Pride sponsorships and queer representation have risen significantly. Through a combination of the changing political climate, a rise of social media and a new generation responding well to diverse and inclusive marketing, it’s no surprise corporations loudly signal their support of queer communities during Pride month.

However, not all marketing moves for LGBTQ+ people have gone smoothly. A recent partnership between Bud Light and trans influencer Dylan Mulvaney catapulted the trans community towards a lot of hate. The sponsored Instagram video involved Mulvaney showing off the beer cans to commemorate a year of her transition to womanhood. Conservative consumers were outraged and reacted by dumping cans of Bud Light, calling for a boycott.

This sparked controversy but nonetheless, great PR and attention for Bud Light. It left Mulvaney in immense danger. She said: “The Bud Light ad had opened her up to more bullying and transphobia than she’d ever experienced” (The Washington Post, 2023). Bud Light made no effort to protect the influencer and has yet to reach out to her, despite all the abuse that has been caused as a result of the sponsorship.

Looking at the past, we can see advertising’s impact on our culture and power of belief.

For many years, the queer community was ignored by society and therefore by ads. Nowadays, companies use queer identities to promote themselves.

Advertising should and has been used to give voices to those who are misunderstood and underrepresented. When representing the queer community, quality representation, good intention and collaboration with the queer community is necessary. The queer identity being represented should be just as important as the corperation or product being promoted.

We should learn from queer advertising history and understand how advertising can be used as a form of activism. But when done poorly, it can perpetuate negative public views of minority groups, in this case, LGBTQ+ people.

The pursuit of profit can lead to a disregard for ethics, honesty and safety. From false claims to bad campaigns, scandals have eroded public trust. Amelie Alcorn uncovers....

First on my list, one of the earlier scandals in advertising dating back to the late 1920s, when Lucky Strike cigarettes were marketed as a means to achieve thinness for women. Its highly successful campaign featured the catchy slogan “Reach for a Lucky instead of a Sweet,”positioning cigarettes as a healthier alternative to sweets. The irony, right?

This promotion of unhealthy behaviour not only dealt a blow to the sweet industry but also, as highlighted by Stanford research on Tobacco Advertising, “preyed on female insecurities about weight and diet”. This led to a wave of marketing campaigns specifically targeted at women. These used mainstream beauty and fashion standards to entice women to present smoking as a feminine activity.

The impact of this campaign was significant, with sales of Lucky Strikes soaring by over 300 per cent in the first year, establishing it as the top cigarette brand nationwide.

However, the campaign later faced deserved scrutiny from health advocates and government officials and was eventually derailed by the threat of litigation from the sweet industry. Ultimately, Lucky Strike dropped it, but not before it attracted both loyal customers and fervent critics.

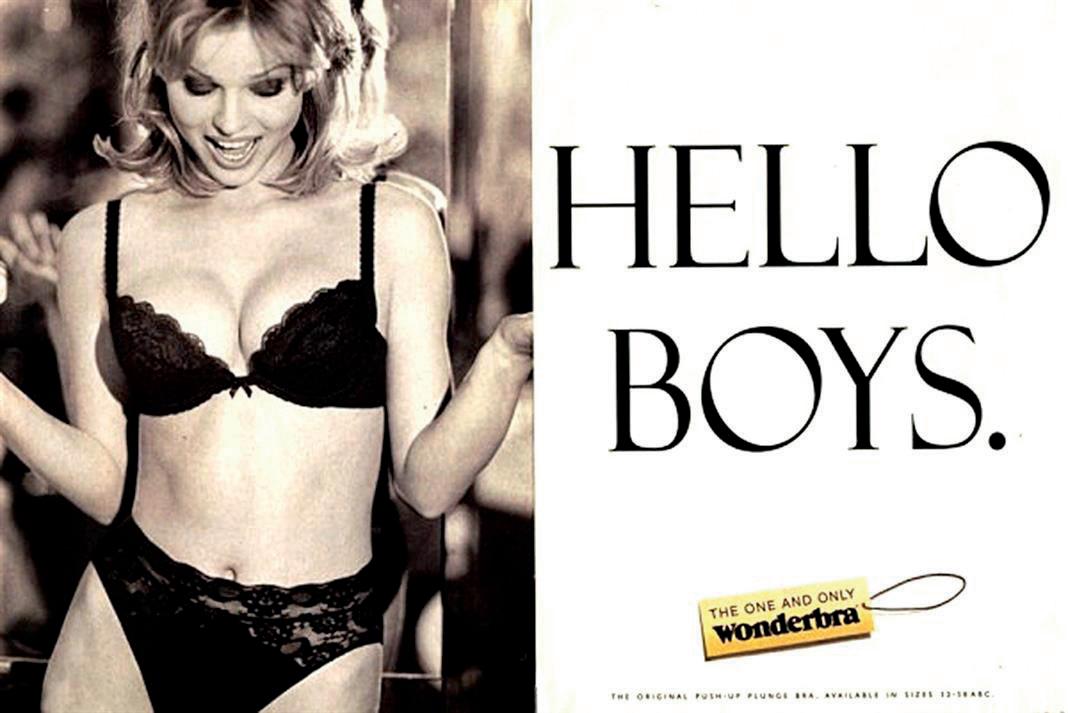

But the exploitation of women and their insecurities ceretainly doesn’t end at cigarette campaigns. Take Wonderbra’s famous Hello Boys advert, the 1994 billboard that reportedly stopped traffic. The ad features a Czech model, Eva Herzigova, dressed only in Wonderbra underwear, gazing down at her assets and remarking “Hello Boys!” Is she addressing her bust or any male onlookers? Of course, the copy was intended to be equivocal, but if the rumour is to be believed then the billboards proved to be so distracting to male motorists that the ad caused many traffic accidents. However, this wasn’t the only controversy attached to the brand. Wonderbra has been dogging accusations of sexism for years with the creative

Bodies as

...or how women have been objectified by adverts for everything from cigarettes to bras 1

teams behind the campaigns being predominantly male. But why should women’s underwear be advertised so that it appeals to men?

As of today, Wonderbra continues to generate controversy. The previous slogan has been replaced with “Hello me!”, a caption aimed at promoting female self-empowerment. However, feminists argue that the campaign is simply a case of “same nonsense, different era”. Julie Bindel, co-founder of the legal reform group Justice for Women, strongly criticized the company, stating that women in this era will not be deceived into considering the posters as empowering.

She remarked, “We are being fed the guff that the new slogan is less about appealing to sleazy men and more about targeting ‘empowered, liberated women’. If you ask me, [this] is the same nonsense, different era”. Despite ongoing efforts to address these issues, the advertising industry continues to grapple with deep-rooted problems of sexism and objectification. Carl’s Jr.’s highly sexualized burger advertisements, promoting their “all-natural” beef burgers, serve as a prominent example. Linsey Davis, a vocal advocate for Diversity and Inclusion, has rightly highlighted the fact that in one of their commercials, featuring a model dressed in revealing attire, it takes a significant 28 seconds out of a 42-second video to realize that it is, in fact, an advertisement for a fast-food company. Adweek editor Lisa Granatstein openly acknowledged in an interview with ABC News’ Good Morning America that these ads intentionally target men, disregarding potential controversies and emphasizing that more controversy ends up benefitting them.

Consistently reducing women to mere objects of desire or eye candy perpetuates harmful gender stereotypes, which ultimately contribute to gender inequality and discrimination. It is disheartening that even in 2023, we must still call out these offensive and outdated tactics. One can only hope that these brands will learn from their past mistakes and genuinely embrace a more inclusive and respectful approach in the future.

...or how Pepsi proved we still don’t learn from the past

...or when advertising goes seriously wrong

Issues of diversity and representation have plagued the industry for decades. While these scandals have gained more attention in recent years, the presence of stereotypical and discriminatory ads has a long history.

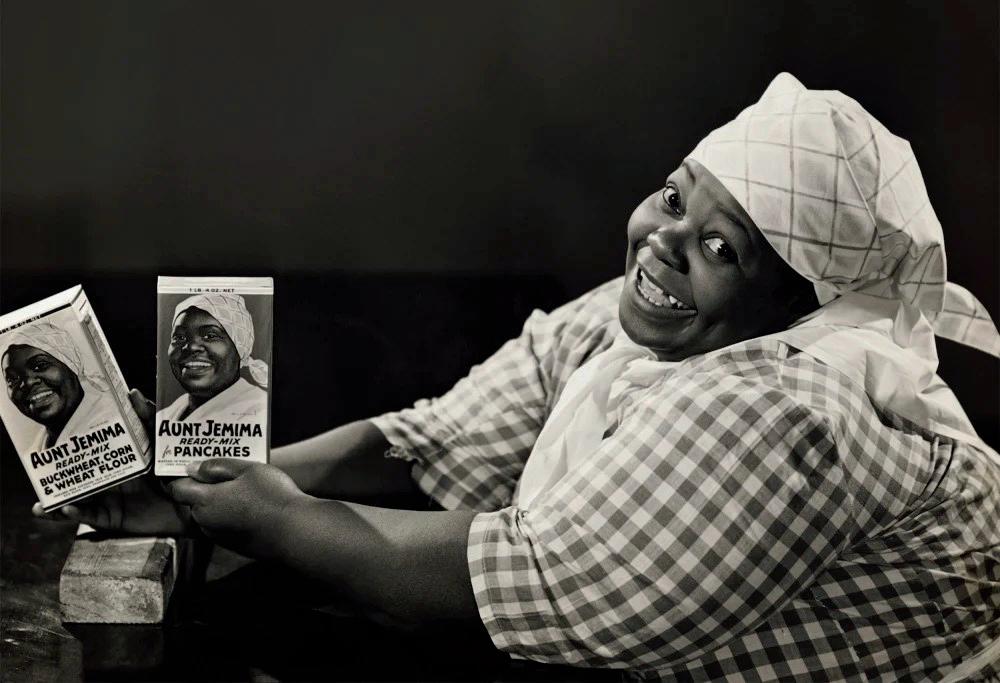

Take Aunt Jemima, an American breakfast brand for pancake mix in the late 1800s that depicted a Black woman in a subservient “mammy figure” role. Similarly, Uncle Ben’s Rice, owned by Mars Inc, featured a racist “happy black cook” figurehead. Even toothpaste ads in the 1950s portrayed a Black man who, after using the product, magically lightened his skin and gained acceptance from white people. This was uncannily similar to the more recent Dove advert which depicted a black woman turning into a white woman after supposedly using its body lotion. Dove’s marketing team should have known better and apologised swiftly. Nevertheless, these few examples highlight the persistence of harmful stereotypes and discriminatory practices in advertising.

As Kristen Rogers, an Associate Writer for CNN Health pointed out, there is a subtle and insidious form of racist stereotyping that can be challenging to identify. Even celebrities with significant social influence have, without supposedly realising, taken part in this discrimination. The 2017 Pepsi ad featuring Kendall Jenner exemplifies this. It depicted Jenner leaving a photoshoot to join a protest where activists from

Lesson No1

The cornerstone of effective advertising lies in understanding your audience. Countless brands have faced failures due to a fundamental lack of comprehension regarding the individuals they sought to captivate. To leave a lasting impression, marketers must immerse themselves in the complexity of their target market, peering into the depths of their interests, values and needs.

diverse ethnic backgrounds carried signs of peace and love. As Rogers observed, the scene reminded viewers of past instances of excessive force and violence against activists during protests. However, the ad took a problematic turn when Jenner handed a can of Pepsi to a police officer as a peace offering, seemingly resolving the tension.

Critics took to social media to express their disapproval. Entertainment Weekly labelled the ad “tone-deaf,” accusing the company of attempting to exploit a political movement for commercial gain. On platforms like Twitter, numerous users voiced their concern and disgust, highlighting how the ad trivialized real-life protests in which lives were lost while fighting for genuine causes, one user commented “the worst thing about that Pepsi ad, beyond the blatant disrespect and disregard, is the amount of people who greenlit that advertisement”. Many individuals expressed their disdain for Pepsi positioning itself as a solution to deep-rooted social problems, finding such a portrayal distasteful and inappropriate. Kendall Jenner publicly apologised, expressing regret for her involvement.

Despite the lessons learned from the past century, it is disheartening to witness the repetition of these mistakes in the 21st. The harm caused by such ads cannot be overlooked, and it is crucial to acknowledge and rectify the negative impact they have on marginalized communities.

Lesson No2

Adherence to the ever-evolving tapestry of cultural and societal norms is paramount. The consequences of offending or alienating consumers are dire, spelling swift relegation to the archives of irrelevance. Staying attuned to current trends and remaining with the zeitgeist is essential for maintaining a firm foothold in the limelight.

Lesson No3

Honesty serves as the bedrock of an enduring advertising campaign. The perils of disseminating misleading or deceptive ads cannot be overstated. Such practices can erode credibility and tarnish the hard-earned reputation of brands. Embracing transparency and integrity safeguards the coveted position within the advertising realm.

One of the highest-profile scandals in recent years revolved around Facebook and Cambridge Analytica. In 2018, it came to light that the political consulting firm had surreptitiously obtained raw data from million Facebook users worldwide, without their consent.

The data had been collected through a quiz app developed by Cambridge researcher Aleksandr Kogan who then sold it to Cambridge Analytica. This data included users’ personal information, such as names, locations, likes, and even the data of users’ friends.

The repercussions were far-reaching, as the harvested info was exploited to influence major political events such as the 2016 US presidential elections and the Brexit referendum. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg vowed to make sure it would never happen again.

The failure to safeguard users’ information resulted in a $5 billion fine imposed by the US Federal Trade Commission. It sparked widespread calls for stringent regulation of the tech industry and ignited a broader debate on the ethical use of personal data in advertising and marketing.

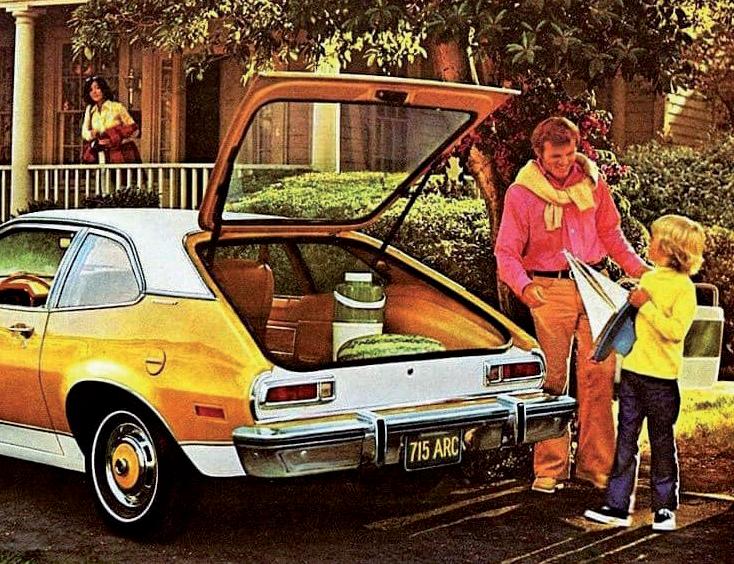

In the realm of corporate wrongdoing, one particular incident stands as a stark reminder of the dire consequences when ethics take a backseat. The Ford Motor Company disaster unfolded in the 1970s, with the introduction of the Pinto (pictured) , a cheap and compact car that was marketed as “The Little Carefree Car”. However, behind the enticing advertisements lay some grim facts. Rushed into production, the car was a ‘death trap’ and Ford knew it, but deliberate decisions not to modify the design were made to protect corporate profits.

Tragically, the defective design resulted in the loss of 27 lives including a 13-year-old. However, when the case reached the courtroom, a not-guilty verdict was delivered due to a lack of concrete evidence—a glaring miscarriage of justice.

Ford’s actions were not only cynical but also complicit in the perpetuation of an advertising campaign that concealed the grim reality. A multimillion-dollar ad spend extolled the virtues of the Pinto while disregarding the potential harm it could inflict on unsuspecting consumers. This was a

While referencing other media texts, such as movies or books, in an ad can be considered clever and creative, it might just be a lazy way of appealing to a large, unrelated market. Theo Martin dissects two high-profile examples of intertextuality in advertising

American snack brand ‘PopCorners’ aired an advert relying heavily on intertextuality at Super Bowl LVII, February 2023. The advert, Breaking Good, is a parody, based on the extremely successful AMC television show Breaking Bad (BB), featuring characters Walter White (Bryan Cranston), Jesse Pinkman (Aaron Paul) and Tuco Salamanca (Raymond Cruz). The advert spoofs BB, replacing the manufacture of methamphetamine with the creation of PopCorners snacks.

Several references to the show are made, including the iconic recreational vehicle meth lab and lines such as“Yo, these are the bomb!” and “Say their name!”, amongst others.

According to Illumin, Breaking Good was the 10th most watched ad of the 2023 Super Bowl, racking up 37,434,115 views. The 30-second slot was likely to have cost around $7 million.

It is hard to argue with the impact of such a high-profile advert from the commercial point of view, but creatively I would argue this advert uses intertextuality in a lazy way. The relationship between a meth-based drama and the snack is tenuous and irrelevant. In this advert, PopCorners is obviously trying to promote its product to the masses by aligning itself with IMDb’s third highest-rated TV show of all time

The context of the advert only emphasises the laziness of the creative strategy. Cranston and Paul’s last appearances as White and Pinkman were in one episode of the BB spin-off series Better Call Saul in August 2022, and it had been a full ten years since the final season of BB ended. So any sort of reference to the show, in any media would highly likely generate a wild amount of publicity across social media.

This shows how heavy-handed intertextuality is often a sign of a risk-averse marketing strategy. It is much safer to use a popular show with a pre-engaged audience than earn your own fans.

Instead of trying something new and original, the creative team have decided to simply spoof an already iconic programme.

However, according to Benjamin Hiorns, writing on Creativepool: “Parody ads may seem lazy on the

ABOVE: A still from the advert spoof of AMC drama Breaking Bad for PopCorners, 2023

surface but dig deeper and you’ll find they require a certain degree of creativity, wit, and technical proficiency.” This is a relevant point as the jokes and references in the advert do show a level of cleverness.

But the fact that BB has very little to do with crisp-like snacks far outweighs the wit of the script. Hiorns does concede in the same article: “The key to a good parody is in the depth of appreciation for the source material.”

In the PopCorners ad, the source material, BB, is being appreciated but not applied in any relevant context and, therefore, the effectiveness of the comedic writing is undermined by the mostly irrelevant product placement.

‘Heavy-handed intertextuality s often a sign of a risk-averse marketing strategy. It is much safer to use a popular show with a preengaged audience than earn your own fans

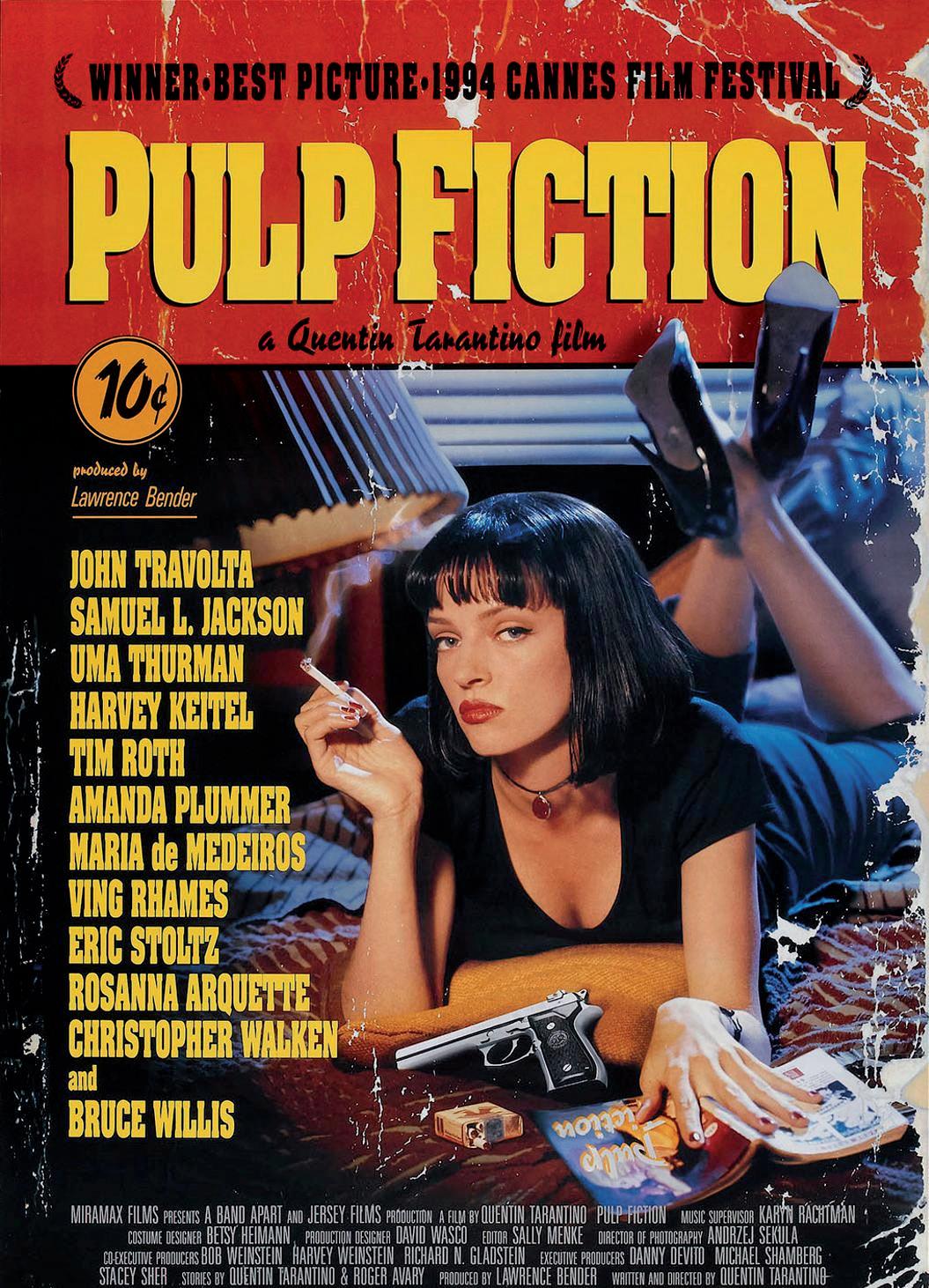

In 2015, UK-based insurance company Direct Line released a series of adverts featuring Harvey Keitel as the infamous Winston ‘the Wolf’ Wolfe, from Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction. In the film, Winston Wolfe is a gangster and ‘fixer’ who aids hitmen in cleaning up their victims’ remains after a killing. Saatchi & Saatchi, the agency behind the Direct Line adverts, took the idea of Wolfe’s role as an efficient and competent problem-solver, and compared this to Direct Line’s quick and simple service. The adverts depict the average Direct Line customer facing a stressful insurance-related problem, such as a crashed car or an electrical fire at home, with Wolfe explaining how Direct Line can help them in this situation.

The tone of these adverts differs greatly to PopCorners: Breaking Good. It is a much more creative use of intertextuality as the character of Wolfe is comparable to the benefits of investing in insurance. While PopCorners are only using the BB brand to attract new consumers, Direct Line are familiarising themselves with potential customers and offering stronger justification for the appearance of such an iconic character.

The intertextuality fits - it is an essential part of the original idea. If you were to change the name of Winston Wolfe in the Direct Line adverts, you would still have a narrative, call to action, and benefits of the service. If the recognisable characters, dialogue, settings, and narrative were removed from the PopCorners advert the only content left would be a pack shot. The Direct Line adverts are clearly more creative as the narrative and themes of the adverts are all original compared to the PopCorners’ narrative taken wholesale from BB.

Equally, the film that the characteromes from is itself an incredibly intertextual film. Pulp Fiction is rife with references to celebrities, products, music, TV shows and other films, and even Tarantino’s own films. Multitudes of fans and movie critics alike have dedicated themselves to finding each individual reference and at the time of writing they have counted a whopping 182 instances. The fact that Winston Wolfe is being used intertextually could be an (albeit rather farfetched) intertextual reference in itself.

RIGHT: Poster of Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, 1994, which features Havey Keitel as Winston Wolfe who was adopted by Direct Line in 2015, inset

Is using intertextuality in advertising creative or lazy? In most cases, I would argue that intertextuality is still a valuable creative tool that can be employed to create meaning and single out new markets.

But deciding on appropriate media texts to refer to requires thought and skill. A weak reference can lead to audiences feeling alienated, but a strong reference can create persuasive, precisely targeted advertising. An intertextual reference becomes lazy when the referred to text has nothing to do with the product or service, and is there simply to bait fans via association with their favourite media product.

Another lazy use of intertextuality is where an advert relies too heavily on the narratives, characters, settings, and dialogue of the referenced text. Every aspect of the advert is borrowed - there is nothing original, as seen in the PopCorners advert.

There is a fine line between lazy and creative when incorporating existing work into new adverts. It is a risky strategy insfar as the reference might not ‘land’ with the intended market.

But it is also risk-averse: there is a guaranteed market for the advert, should the reference be properly executed.

Most importantly, an advert that uses intertextuality, if it aspires to be creative rather than lazy, must be able to stand without the referenced text.

The intertextuality fits - it is an essential part of the original idea. If you were to change the name of Winston Wolfe in the Direct Line adverts, you would still have a narrative, call to action, and benefits of the service

On the 20th of May, 1873, blue jeans were born. On this day, Levi Strauss and Jacob Davis obtained a US patent for putting rivets in men’s work pants for the first time. Blue jeans, as we know them today, were not produced until the 1920s. At that time, they were mainly used as work pants in the American West. It wasn’t until the 1950s that blue jeans became popular among young Americans for their style, comfort and durability. Their jeans were cool, but not sexy.

Calvin Klein changed that. It’s brand identity has been built by provocative ad campaigns that have captured audiences and sparked conversations over the years.

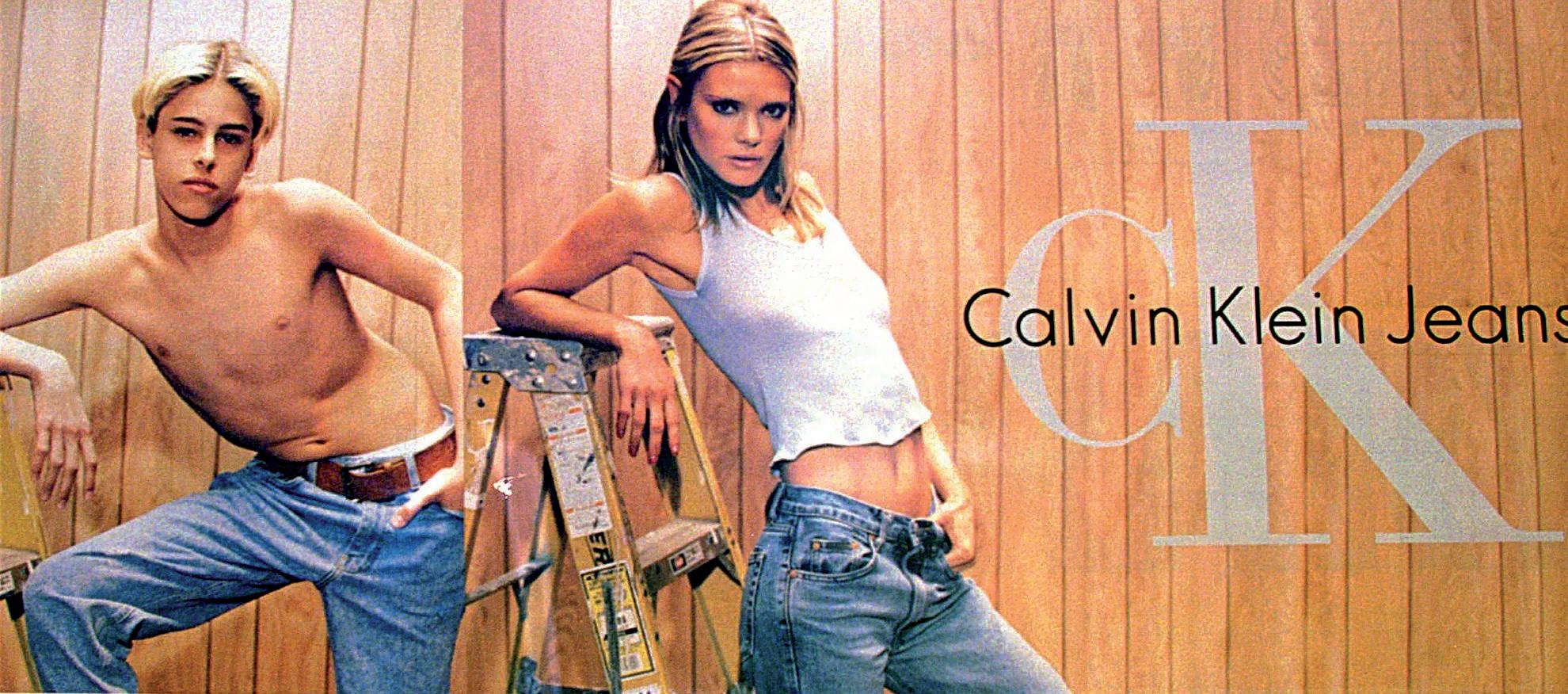

Klein seems to thrive on controversy. In 1980, two campaigns caused an uproar. One was The Feminist with the seemingly suggestive tagline “Nothing Comes Between Me, and My Calvins” featuring 15-year-old Brooke Shields. The other was The Teenager with Klein yet again choosing seductive wordplay: “If My Jeans Could Talk, I’d Be Ruined.”

Some TV stations banned these commercials after viewers’ complaints. Klein was not discouraged. He believed that “jeans are about sex” and continued to sell his products using this approach. “I didn’t set out thinking how to be controversial,” Klein told WWD in 1994. “With Brooke Shields years ago, I thought it was a hoot, but all these people went crazy. We need newness and excitement in fashion. That’s what it’s about - that’s what puts the fun in fashion... We’re always questioning people’s values. How much can you provoke? How much are they willing to show? Is it decent? Is it exciting? Is it valid? Is it over the top? It’s a whole process, but it’s not about trying to be controversial or trendy.”

These advertisements pushed the limits of societal norms, creating controversy and intrigue around the brand. Despite Klein’s controversial tactics, his 1995 campaign, featuring childlike models such as 17-yearold Kate Moss, sparked significant outrage and was

We’re always questioning people’s values. How much can you provoke? How much are they willing to show? Is it decent? Is it exciting? Is it valid? It’s a whole process but it’s not about trying to be controversial

By daring to be different, Calvin Klein has made jeans sexy. Issie Dexter explores Klein’s marketing journey, questioning its ethics and examining its controversial path to success

considered one of the most controversial campaigns in American history. The CK 1995 ad angered parents and child welfare authorities, as they believed it resembled child pornography. These objections led to an FBI investigation into Klein and his in-house agency, CRK, for violating child pornography laws.

Although no evidence of wrongdoing was found, Klein pulled the campaign. This started Klein’s career of generating free publicity through shock tactics. He understood that creating a small amount of the right noise could result in millions of dollars worth of free media coverage.

The use of celebrity sex appeal is still in CK marketing. On January 4th 2024, Calvin Klein released My Calvins or Nothing, featuring heartthrob actor Jeremy Allen White. It initially caused an online frenzy among fans. After the actor’s half-naked photos appeared on Calvin Klein’s famous billboard in the centre of New York’s SoHo area, the frenzy only became stronger. And when a video featuring a dozen doves shooting into the sky and a ripped Jeremy AllenWhite sprawled out on a couch wearing nothing but his underwear and trainers was released, the campaign became a full-blown media sensation.

It was a classic Calvin Klein move to stick the heartthrob in a pair of jeans and strip them down until little is left for the imagination. What else would we expect from a brand that built itself with alluring conversation-starting campaigns since the 80s?

Calvin Klein’s advertising campaign began with Whites ad, but it didn’t end there—of course, there was going to be something to provoke backlash…

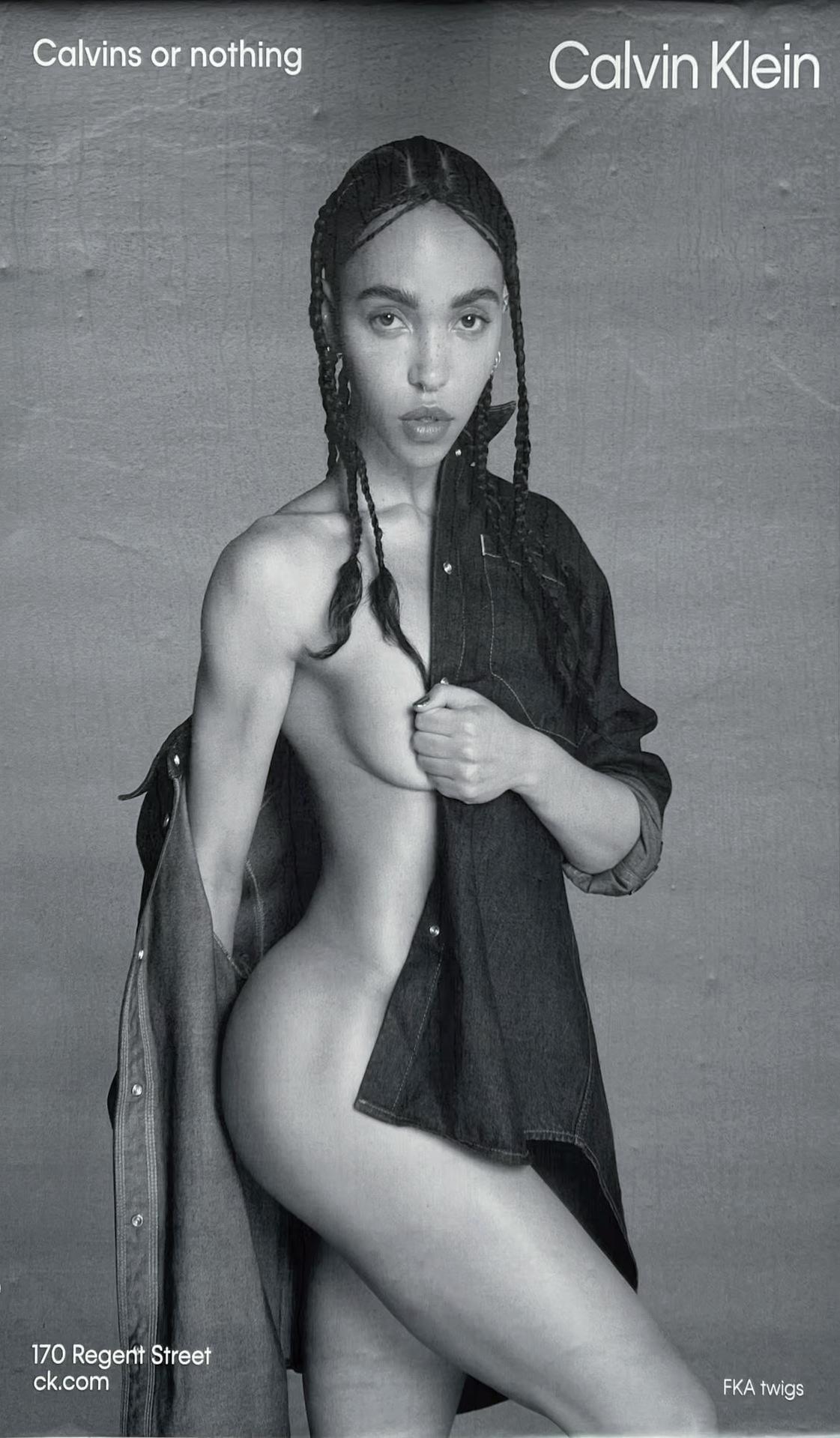

Singer and actress FKA Twigs joined the campaign, appearing on billboards with a portion of her breast and the side of her buttocks exposed while wearing a shirt bearing the “Calvins or nothing” slogan. On January 10th, the UK’s Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) banned the advert, based on the notion that the images focused on her “physical features rather than the clothing, to the extent that it presented her as a stereotypical sexual object.”

In the original ruling, the authority deemed the ads were unlikely to offend based on objectification. However, ASA has now reversed its decision, stating that the image is “overtly sexual” and that the billboards should be banned so that those under 16

The ASA is right to be cautious about overly sexualised messaging, but we should apply the same scrutiny to ads featuring men. Banning her campaign while not taking action against his smacks of gender bias

could not see them in an “untargeted medium”.

FKA Twigs highlighted the double standards in the industry. Alongside a copy of the banned image, she wrote on social media: “I do not see the ‘stereotypical sexual object’ that they have labelled me. I see a beautiful, strong woman of colour whose incredible body has overcome more pain than you can imagine.”

You would think that in 2024 we would be more careful not to place women in awkward circumstances or treat them differently than men. Of course, we shouldn’t return to the days of advertising when women’s bodies were objectified without question. The ASA is right to be cautious about overly sexualised messaging, but we should apply the same scrutiny to ads featuring men. Banning her campaign while not taking action against White’s campaign smacks of gender bias.

Klein has still managed to ruffle the ASA’s feathers with its audacious imagery, capturing the public’s attention and raising serious conversations about the use of female bodies in advertising.

Calvin Klein effectively positioned itself as a brand that challenged conventions and captured consumers’ attention. By stoking controversy and pushing the boundaries of societal norms, it became a go-to choice for those who looked for an edgier and more provocative fashion choice, cementing the brand’s image as daring and fashion-forward.

How did the company achieve this? Klein saw an opportunity in the market. Jeans were functional, casual and youthful, but not sexy. He took this and ran with it, advertising with a seductive tone to change the narrative of what jeans could be.

However, Klein’s seductive voice wasn’t the only element contributing to his success. He used celebrity endorsements, strategically choosing popular figures in the public eye, such as Brooke Shields, Kate Moss, and Mark Wahlberg. By doing so, it could reach its target audience effectively. As most young people wanted to be these celebrities, this strategy worked well.

But the history of their campaigns should also remind us to take care when using provocative imagery and always to question the ethics of our creative choices. Are the models too young? Are you objectifying certain groups in society? Is the use of this imagery necessary to sell your product?

In conclusion, Calvin Klein’s controversial strategy has taught us that celebrity endorsement is everything, that we should be a part of cultural conversations, and that we should not be afraid to push the boundaries of social norms and take risks. There will always be an audience that wants to rebel against society’s rules. Last but not least, advertise with the tone of voice you want your product to be perceived as. For example, are you bored of jeans being sold as functional and casual? Change the narrative, make them sexy, and seduce your audience.

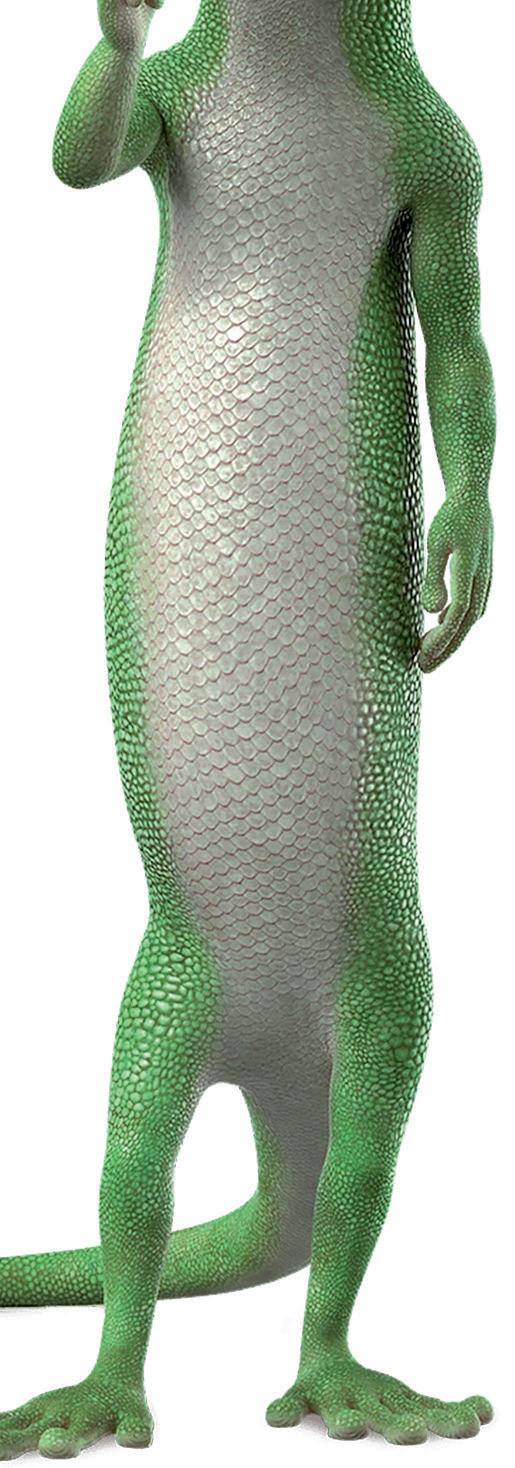

Becca Mortimer explores the weird and wonderful animals of insurance: geckos, ducks, bulldogs and meerkats. Why are these fun characters paired with such a dull industry and how have they left their lasting paw print in wider pop culture?

Insurance policies: tedious, complicated and boring It’s just another tick in the box you have to complete for a supposed peace of mind. Time seems to drain away as you scroll through the endless options: fees, premiums and compensations – all big words no one really understands. In the end you sign your life away to a company which apparently has the best ‘financial protection’ (whatever that means).

For a long time, the marketing was similarly dull. Corporate logos and droning voiceovers, with an undertone of fearmongering. But then this bland, and let’s be honest, somewhat intimidating subject transformed into a haven of laughs, catchy jingles and most bizarrely... a breeding ground for talking animals.

Advertisers at the Martin Agency recognised the negative relationship consumers had developed with insurance and saw a gecko-shaped gap in the market. American insurance company, GEICO, first introduced their cockney-speaking gecko mascot over 20 years ago.

The green reptile, despite his slim stature, had a huge impact, raising the business’s ranking to second in the US industry.

With GEICO’S wild success, another American insurance company, Aflac, felt added pressure to come up with an innovative campaign to win over the reptilian-loving public. Many people, including Aflac employees, struggled to remember the generic name.

The Martin Agency recognised the negative relationship consumers had developed with insurance and saw a gecko-shaped gap in the market

Repeating it again and again in the office was the only way to get it to stick in their heads. “It’s Aflac – Aflac – Aflac – Aflac – Aflac”. Someone said it sounded like a duck, and long story short, a duck mascot has been quacking the company’s name ever since.

However, the duck idea was not accepted with open wings straight away. When agency Kaplan Thaler was initially pitching the duck idea, the CEO of Aflac said: “The response was always the same: a silent stare.” But creatives knew that Aflac’s biggest issue was the easily forgettable name – and a duck seemed the obvious solution. After a lot of persuading and many studies on the duck’s memorability, they managed to convince the company management to embrace it. It proved to be worth the risk, with Aflac’s name recognition up to 67 per cent after just two years of running commercials featuring the duck.

The duck quickly became a beloved household character, and requests came flooding in for a cuddly toy version of the bird. Insurance had never seemed even remotely interesting to children, but Aflac had quacked the code. Just like insurance ads, children are pushy, repetitive and annoying; they became a constant reminder of the brand as parents across the States were being begged for the “Aflac duck plush”.

The insurance company decided early on that all proceeds from the branded stuffed animals would be donated to Aflac Cancer Centre. Within a few months, $75k had been given to the charity. My Special Aflac Duck ™ is a special robot version, which is given to children with cancer and blood disorders, free of

charge. It even includes an interactive mobile app with calming visuals and sounds.

These charitable intentions created a positive reputation and an emotional connection with its consumers. The President of Aflac commented: “Our purpose is deeply rooted in being there for our policyholders. My Special Aflac Duck stands as a tangible symbol of that dedication.”

Across the pond in the UK, Churchill Insurance decided they wanted to join the animal mascot bandwagon. They adopted a bulldog, a traditional symbol of British identity. It developed into a nodding

dog called Churchie, and within a year of his ‘birth’ they began selling models of him. Voiced by famous Yorkshire comedian, Bob Mortimer, the dog’s slogan “Oh yes” became synonymous with the brand.

Churchill recently underwent a rebrand, by the agency Engine Creative. Creative Director Paul Jordan commented: “Brand love can slip into overfamiliarity if you’re not careful.” They decided to remove the anthropomorphic aspect of their mascot, and replaced the original with a CGI equivalent, in the hopes that they could reach a younger, contemporary audience. Despite the new campaign urging busy consumers to “Church… Chill”, people were certainly not chill about this change. Many did not approve of the modernisation of the classic branding.

The insurance company received further backlash when animal rights group PETA claimed that Churchie was boosting the popularity of flat-faced breeds. British bulldogs are more perceptible to health

issues, including breathing problems and ulcers in their skin folds. This is an example of an unintended controversy. Businesses should think carefully about what they’re representing before producing any form of advertising, especially longterm brand mascots.

Another British insurance company with mascots is Compare the Market, who introduced their iconic meerkats in 2009. The idea was derived from the similarity in the words “Market” and “Meerkat”. Somebody presumably had to present this to the client with a straight face at some point, praying that they wouldn’t get fired for being completely ridiculous.

Their main mascot, Aleksandr Orlov, has become something of a national ad break celebrity. His aristocratic attire and Russian accent are now part of the tapestry of British pop culture. Orlov’s catchphrase “Simples” became so widespread it was added to the Oxford Dictionary, and there is now a whole family of meerkats.

Compare the Market is known for the wide range of rewards and extras included in its service, such as

‘

This is a prime example of silly excellence in advertising. What started as a very ‘simples’ concept had space to grow and develop over time, becoming a long-lasting brand identity

Meerkat Meals and Meerkat Movies offers. Much alike Aflac, it also also offers toy versions of its mascots. They have become collectables, with some fans investing in the insurance purely to get the dolls. The most ‘desirable’, special edition meerkats are now going for over £100 on eBay.

This is a prime example of silly excellence in advertising. What started as a very ‘simples’ concept had space to grow and develop over time, becoming a long-lasting brand identity. We can learn from Compare the Market’s bold and creative move that risky ideas sometimes pay off bigtime.

To conclude, the silliness of talking animal insurance mascots has taught us valuable lessons for creating memorable, long-term advertising campaigns. Stripping it back to the plain and obvious – like saying the company name again and again until something forms. A basic concept can blossom into something truly wonderful, and from there everything else falls into place.

That’s not to say it doesn’t take time to develop; becoming a national sensation does not happen overnight. You can ask Mr Aflac Duck himself. It took at least a couple of months for our feathered friend to establish himself in the audience’s hearts and minds.

What’s more, it is not easy to be an animal mascot in today’s society. Being at the forefront of a serious business comes with a lot of responsibility. Companies must be cautious to avoid scandals and being cancelled.

Insurance companies deliberately target children and younger audiences with their anthropomorphic counterparts. Their fun and playful characters stick in kids’ brains. When paired with benefits of free toys, it becomes the children who pester and remind the adult consumers to look into these services.

Oh yes! Maybe it does seem ridiculous at first but there is method behind the madness of these strange creatures of insurance advertising, and it’s all thanks to a lime green gecko from East London.

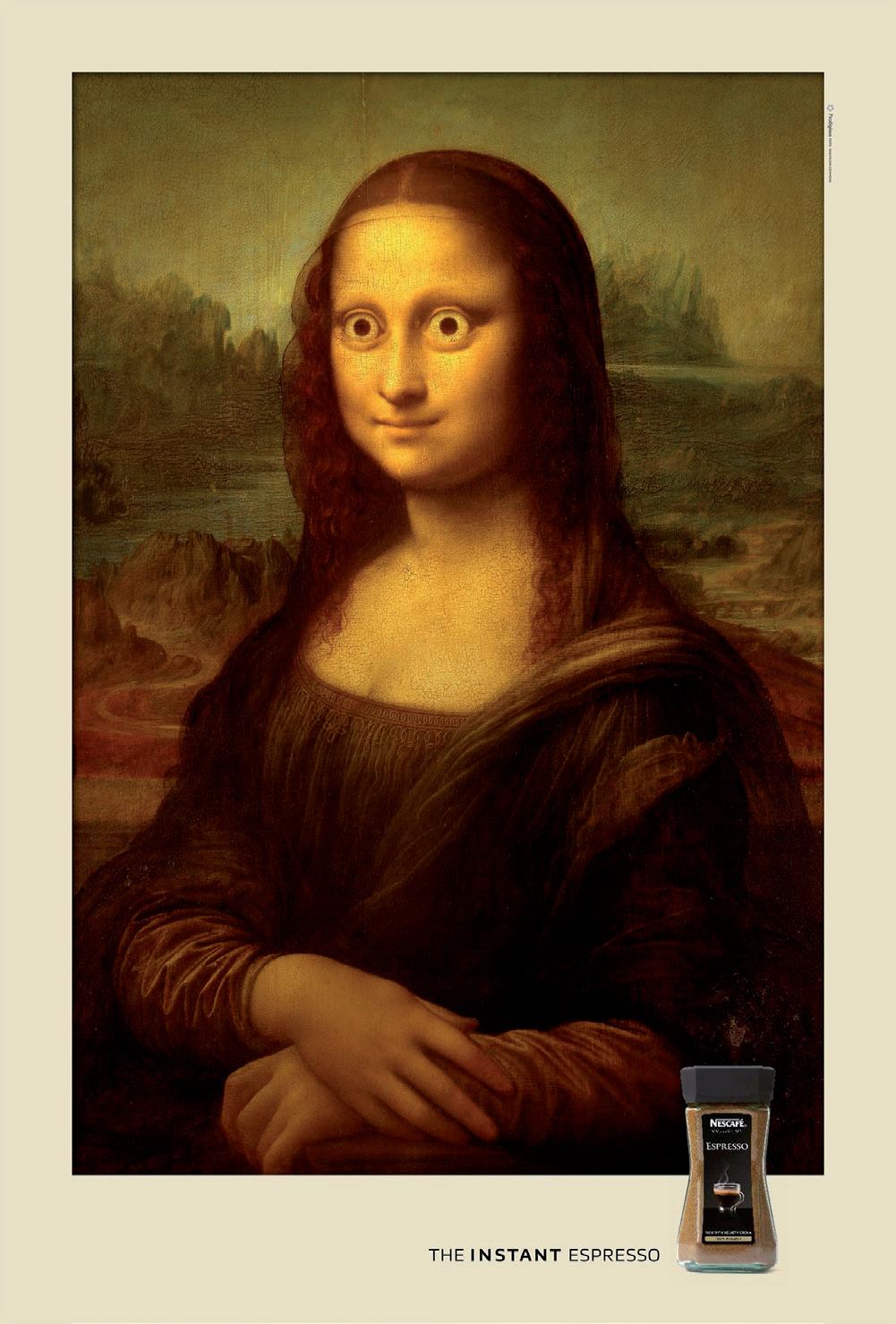

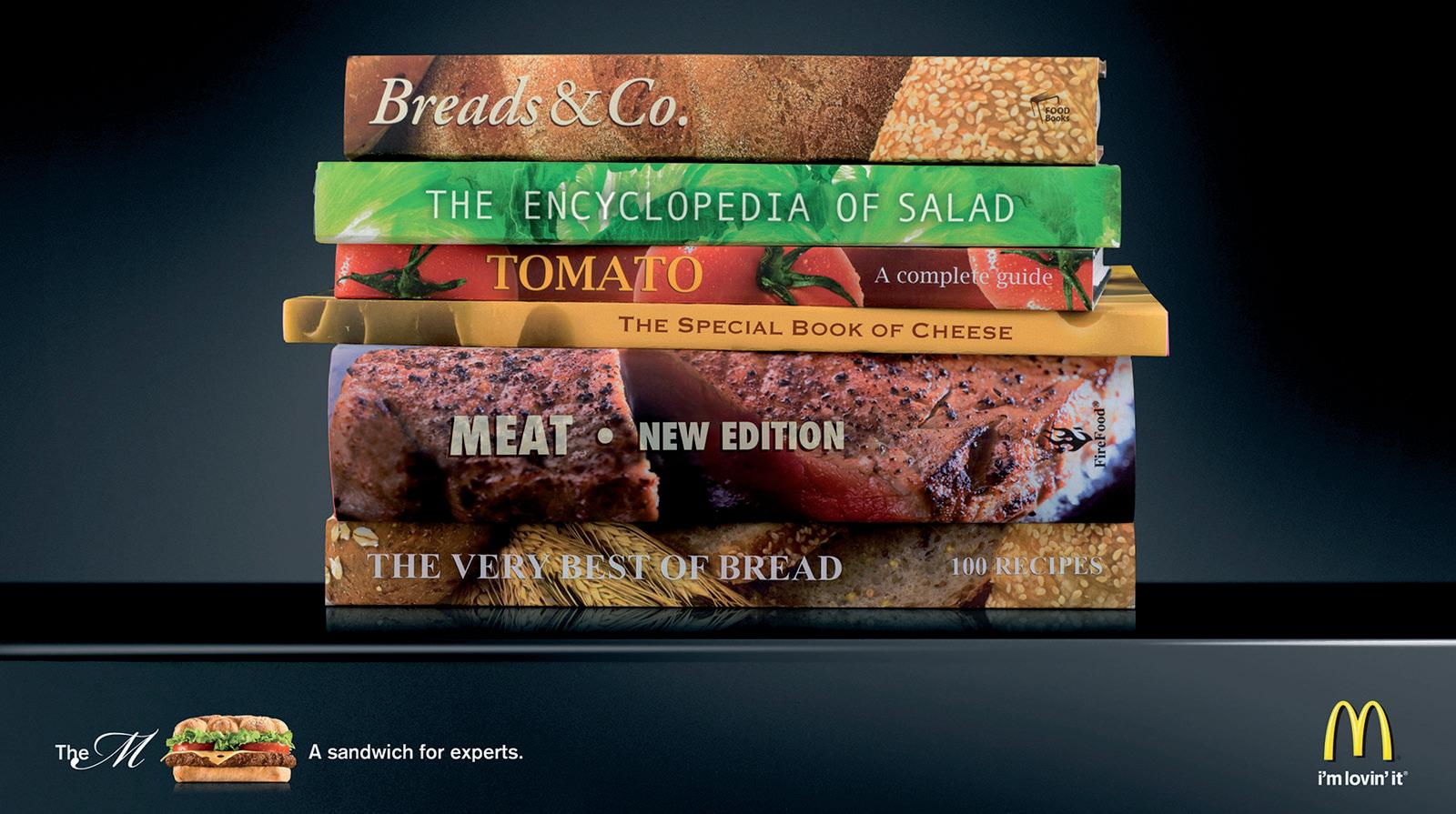

Advertisers have been using art for centuries to flog everything from schizophrenia medication to chewing gum. But is it lazy? Is it ethical? Daisy Hawker explores...

Artvertising is a term referring to the use of art as advertising to persuade potential consumers to engage with a brand. The origin of the term is unknown - it’s likely that it was a naming convention used casually and then spread by people in the marketing industry. Ranging from iconic historical fine art pieces used in ads, to art commissioned for use in adverts, to adverts from the past now seen as art, “artvertising” can be seen everywhere.

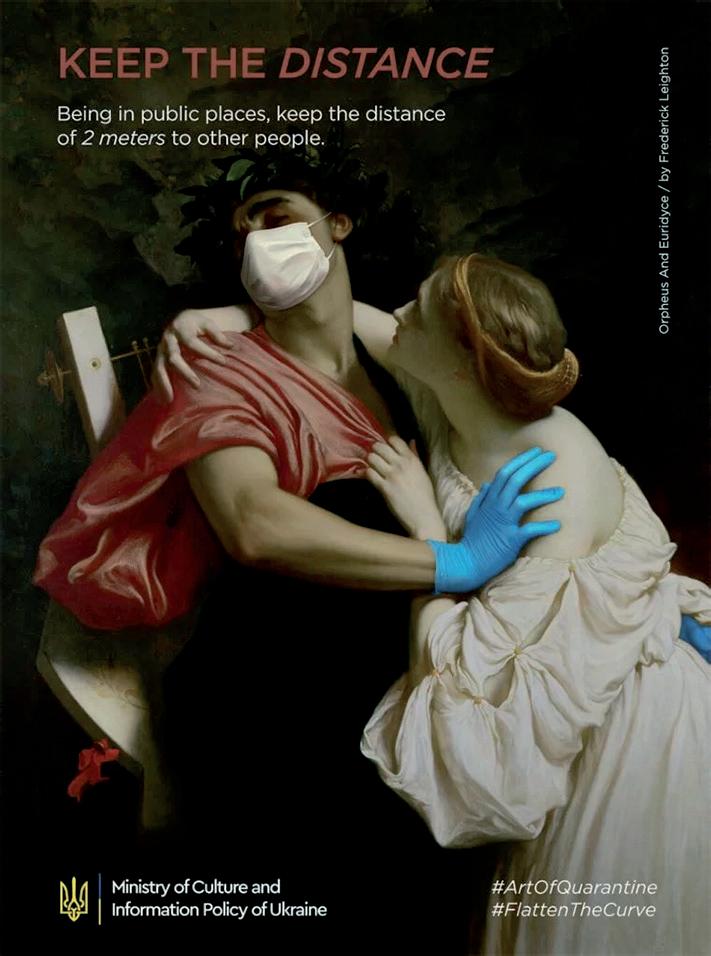

Fine art featured in print ads can make even the most monotonous work eye-catching and memorable. For example, the Ministry of Culture and Information in Ukraine created a COVID-19 informational ad featuring Frederic Leighton’s iconic painting Orpheus and Eurydice (shown right). The aim was to reinforce the concept of social distancing and the painting fits in perfectly with this as Orpheus (the person on the left) pushes away Eurydice and there is a COVID-19 mask covering his face, protecting him. The ad stands out from typical pandemic informational ads and grabs your attention.

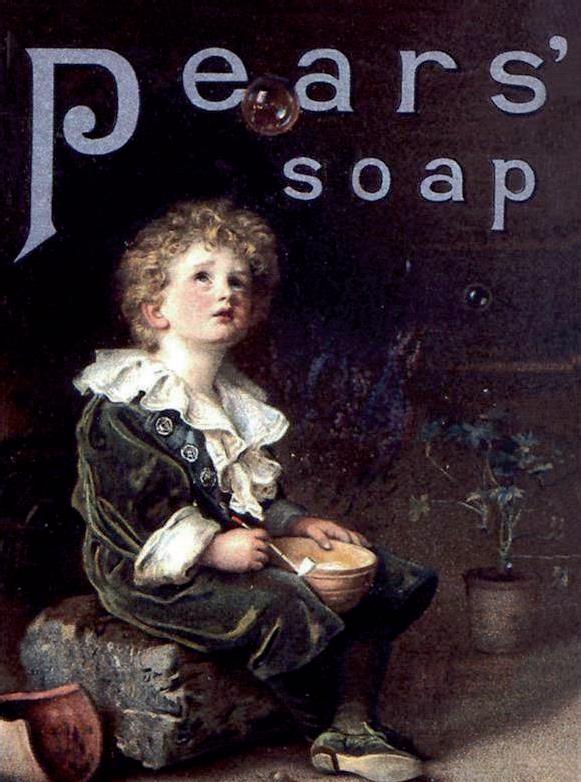

Some would argue that Pears was the pioneer of the artvertising movement. In a time when advertising wasn’t really a thing, Thomas J Barrett, the chairman of Pears, decided to use art to get the word out about Pears soap, creating an advert known as Bubbles. In his book Adland, Mark Tungate explains: “Barrett convinced the popular artist Sir John Everett Millais to sell him a painting of a young boy gazing at rising soap bubbles. Not only that, but he persuaded Millais to add a bar of Pears’ soap to the scene. Queasily sentimental, Bubbles became one of the earliest advertising icons, and set the tone for a highly successful campaign.”

The public were able to purchase prints of the ad, and they were displayed on walls in homes around the world. Bubbles has become a widely recognised, famous advertising symbol and was undoubtedly a success.

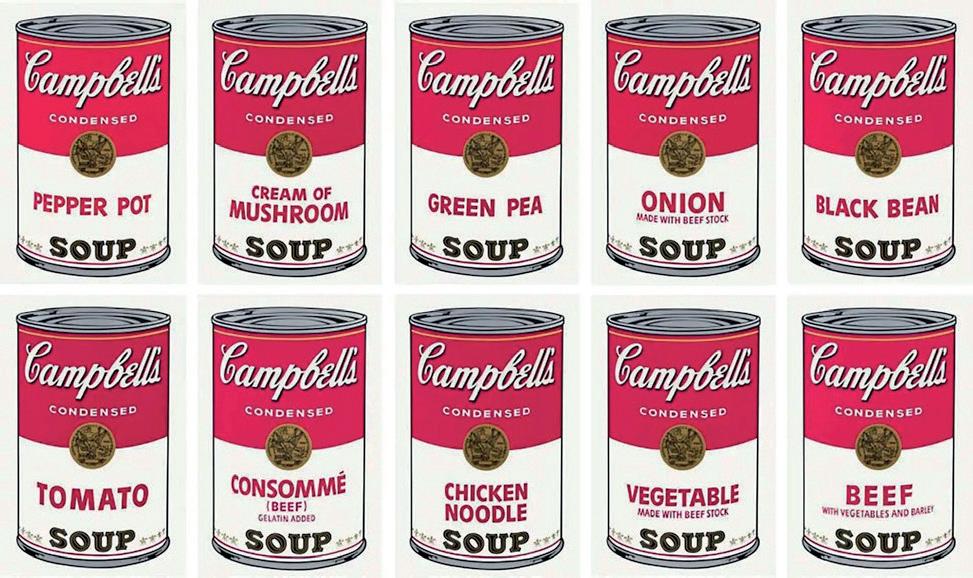

Andy Warhol, the American artist, producer and director, famously painted Campbell’s Black Bean soup cans in 1962, however this was not initially in collaboration with the food giant. In fact, the brand

considered suing Warhol until they recognised the amazing brand awareness the artwork generated. In 1964 Campbell’s sent Warhol a letter of gratitude and crates of soup, then later that year commissioned him to do a painting of their tomato soup can as a gift for its retiring board chairman.

In 1985, Campbell’s commissioned him again to create a series of paintings of their dry-mix soups, creating the iconic Chicken Noodle soup painting. As Ed Carolan, the Vice President of Campbell North America explained, Warhol’s art did more than shift cans of soup: “Campbell’s Condensed soup is [seen

Thanks to Andy Warhhol’s inspired paintings, Campbell’s Soup will always be linked to the Pop Art movement ‘