[A]MAZE

A collaborative showcase of ongoing individual interview projects by MRes Communication Design Pathway students at the Royal College of Art, London.

Acknowledgements

We express our deepest appreciation to all those who supported us in the journey to publish [A]MAZE and made it possible.

In particular, we would like to thank RCA Professor Teal Triggs, Dr Rosa Woolf Ainley, and Dr Laura Santamaria for their instructive and supportive insights on editorial details and proofreading. Additionally, we would like to thank Patrick Lucas, from the Pureprint Group, for his valuable printing suggestions.

[A]MAZE

ISBN 978-1-8381535-8-8

Designed by Yixin Zhang, Fan Zhang

Edited by Labna Fernandez, Zhiping (Sylvia) Xiao

Published by Royal College of Art Kensington Gore, South Kensington London

SW7 2EU UK

Typeface: Univers

Paper: G.F Smith

Printer: Pureprint Group

Printed in an edition of 150

February 2023

All images by individual authors, unless otherwise stated.

© Crown Copyright 2023 Street signage images are published and licenced under the Open Goverment Licence v3.0

© 2023 [A]MAZE, MRes RCA Communication Design Pathway, is licensed under [CC BY-NC 4.0]. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

This document was printed sustainably in the UK by Pureprint, a CarbonNeutral® company and certified to ISO 14001 environmental management system.

Group Statement

[A]MAZE is the exploratory journey of an interdisciplinary collaboration between eight non-native English speakers, communication designers and researchers. The multilanguage experiences of each one of us provide us with insights into communicating across cultures and disciplines. These experiences inform our curiosities in exploring communication processes to different degrees, individually and collectively.

We believe in the significance of mutual exchange of information and subjectivities in communication design research. We investigate this exchange through interviews as a method and through critical practice. We have chosen the interview to establish the bridge between knowing and understanding; to comprehend the dissimilarities and connections between individuals and groups. [A]MAZE addresses the arts and design academic community.

We share a set of five axes for our publication:

a) to be a medium that efficiently carries and conveys relevant information by stimulating and challenging the senses;

b) to blur the boundaries by revealing the unknown and subverting the familiar;

c) to express ourselves to reach out and connect with others;

d) to encourage deepening conversations that make the implicit observable and functional; and last but not least,

e) to discover unexplored paths, bringing pluralities together into one single coherent voice.

Co-authors

Labna Fernandez

Zihan Li

Zhiping (Sylvia) Xiao

Lifei Shan

Fan Zhang

Yixin Zhang

Zhenyi Wei

Zijing Zhong

Design Concept

The design of a book is somewhat similar to building an architectural space. The reading sequence and the structure of the book play an important role in the design process and could potentially influence how readers understand this publication. Arranging the order of eight individual projects was a challenge to the designer. The concept of structuring the book emerged from John Cage’s indeterminacy that segues with the title [A]MAZE.

This publication invites readers to start with an interactive game with the maze designed on the book cover before doing the actual reading. The technique of debossing creates a recessed relief image that mimics a threedimensional maze game. Readers of the book can use their fingers to touch and sense the texture of the cover while playing. This tactile experience allows the hand to interact with the book beyond the action of flipping.

Readers are also invited to use pen or pencils. The page numbers that correspond to each project are randomly printed on the maze, and the different pathway each reader

takes will eventually give them a unique reading sequence of our works. Random selections will produce new interpretations. This publication invites readers to participate in the final stage of making the book’s cover, as well as giving the control of the reading order to the reader themselves. There is a blank space in the biography page for the reader-participants to put their information down to address the idea of co-creation.

For any readers who choose not to play the game, they can always start with page 1. For those who joined this game with a pen or pencil, the book cover accumulates how many pathways and times they have engaged with – from being one edition of a mass-produced identical product, the book has become a unique edition in the world for the owner.

Generally, the maze has an implicated characteristic of trial-and-error, which reminds the readers of the uncertainty and meandering that we encountered in our research journeys.

Introduction

The aim of this publication is to showcase the in-progress individual interview projects carried out by the eight Masters of Research Communication Design Pathway students at the Royal College of Art from our term 1 studies. In many ways, [A]MAZE is the ‘tasting menu’ of our work and of our personal and professional development during the MRes programme.

[A]MAZE is, unironically, a maze. It is a shared space occupied by us, as researchers, as students, as designers. We have taken these exploratory journeys through the maze towards communication using the interview as method. The approaches to the interview are, as you will see, quite diverse and therefore, so are the paths and directions through the maze.

The publication is divided into three thematic sections, Translation, Futurism, and Perception. The first focuses on translation and interpretation. The second looks into relationships, space, speculative, and abstraction. The third, investigates the senses, experience, and cognition. These concepts, perhaps vague at the start, were the scaffolding that brought us all in tune. The collaborative processes have unravelled organically from the human relationships we have established and the gambits we have found to circumnavigate the maze we are immersed in.

We hope this journey and odyssey amaze you as much as it has amazed us!

• We believe in the significance of mutual exchange of information and subjectivities in communication design research.

• We investigate this exchange through interviews as a method and through critical practice.

• We have chosen the interview to establish the bridge between knowing and understanding; to comprehend the dissimilarities and connections between individuals and groups.

Purpose

• To be a medium that efficiently carries and conveys relevant information by stimulating and challenging the senses;

• To blur the boundaries by revealing the unknown and subverting the familiar;

• To express ourselves to reach out and connect with others;

• To encourage deepening conversations that make the implicit observable and functional;

• To discover unexplored paths, bringing pluralities together into one single coherent voice.

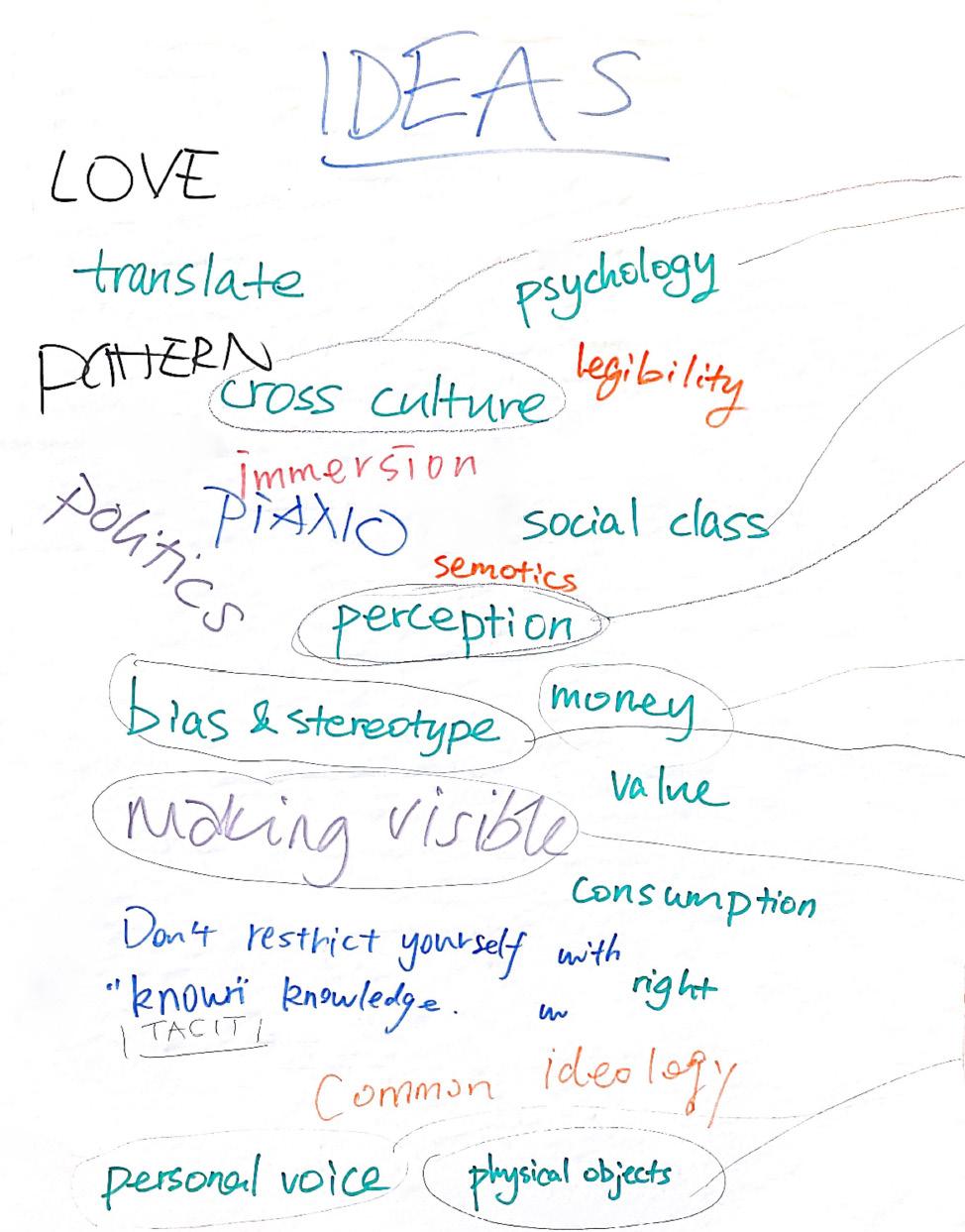

Group Discussion Translation Mind Map

Key Terms

Thematic

Individual Fan Zhang

Interview as Lifei

Collaborative

as a Method

Terms

Surrounding

Abstract Concept

Relationship

Storytelling

Translation

Language

Dialogue

Narrative

Analysis

Futurism

Perception

Shan

Zhang

Yixin Zhang

Zijing Zhong

Zhenyi Wei

Editorial

• Content

• Curation

• Layout

• Copy editing

• Cover binding

• Material

Task Arrangement

Working as Groups

Experiences

• Event Design

• Format

• Equipment

• Curating

• Documentation

• Photography

Publication+Event

Sharing

• Branding

• Campaigning

• Posters

• Dissemination

• Social Media

• Connections

The MRes Group will be holding an event of our actual projects shortly after publication in February 2023 as an extension of the book.

This event documents and showcases our research processes and allows audiences to interact and communicate with our works. We take this opportunity to propose questions and hope to get some feedback.

Questions

Statement Process

Answer Collection

Thematic Analysis

The question isn’t whether the Society’s narrative is biased, but which the bias mechanisms are. How does it impact the popular image of science? How does this steer girls and women away from scientific practice?

The Royal Society's motto, ‘Nullius in verba’, is translated as ‘take nobody's word for it’. This expresses the determination of the Fellows to verify all statements with experiments and to maintain their independence.

The Royal Society is the oldest scientific academy in continuous existence (RS, 2022), since 1660. Due to its influential membership and its near-total control of scientific communication, at least within Britain, it has dominated the development of western-world science. The narrative of scientific history has therefore been constructed primarily under the Society’s norms.

The public perception of science depends largely on the representational practices through which scientific culture and knowledge are presented to and absorbed by the public (T Burns, 2003). Science communication isn't just about transmitting truths but being able to convey risk and uncertainty (Jucan & Jucan, 2014), making facts understandable and accessible to its audience. Descriptions and depictions of nature, science’s object of study, serve purposes beyond representation, they are used to convey affective states on which the production of knowledge through sensory experience depends (Wragge-Morley, 2020).

The scientist conjured in the imaginary is male (Jardins, 2010). Gender stereotypes about who usually is, can be, or should be skilled or successful in STEM subjects underlie the conventional narrative of science and suggest that

men have innate abilities (McGuire, et al., 2020; Mascret & Cury, 2015). Even though not based on any real difference in performance or aptitude, such assumptions often lead to the social exclusion of girls and women from childhood to adulthood, thus contributing to the disparity in gender representation in STEM subjects. Members of the types (classification given to a group of entities with similar characteristics) are not indifferent to their representations, hence there is a causal influence cycle between representations and members of the type (Beeghly, 2015): greater representation affects the idea of who can succeed in STEM (McGuire, et al., 2020). This has widened the gap between the ‘great actors’ of history and the ‘passive and ignorant masses’ (Nieto-Galan, 2011), particularly for girls who do not see themselves represented in the scientific picture. For instance, in 2020 only 11 per cent of the living fellows and foreign members of the Royal Society were women. The lack of commonalities with role models depresses girls’ hopes and ambitions by representing unattainable goals (Laird, 2007).

Despite the presumption of an objective science, scientists and science communicators are socially involved epistemic subjects (McManus, 2016), so their discourse is always inevitably embedded in a social context that shapes what is studied (or ignored) and how (Schiebinger, 1987).

The idea of universal objectivity has reinforced the notion of epistemic institutionally endorsed authority of scientific knowledge, which has led to a phenomenon of epistemic injustice. Prejudices, structural or otherwise, in the economy of credibility and collective hermeneutical resources, along with predetermined masculine thinking, place the feminine as inferior.

Certainly feminism has changed science, but has it changed it enough? Presumptions made, questions asked, and ends sought must change so that the woman scientist ceases to be an oxymoron (Jardins, 2010).

I am in conversation with the Royal Society as a highly influential scientific institution to understand how the telling of its story has (re)shaped our understanding of the natural world, knowledge, and value. I have assembled a historical

reconstruction by mapping the traces of the Royal Society, looking closely at how the Society has publicised itself, its fellows, and its activities, from its foundation in 1660 to the present day. After this dialogical analysis, I will attempt to retrieve the forgotten and retell the Society’s history through the voices of those buried in the oblivion.

‘Nullius in verba’ implies the promise that fellows of the Society will be ruthlessly critical both with each other and the rest of the learned world (RS, 2022). But what about the readers, the outsiders, the audience? What about us? Are we not supposed to be ruthlessly critical of the statements made by the Society? Are we supposed to just take its word for it?

I say we don’t.

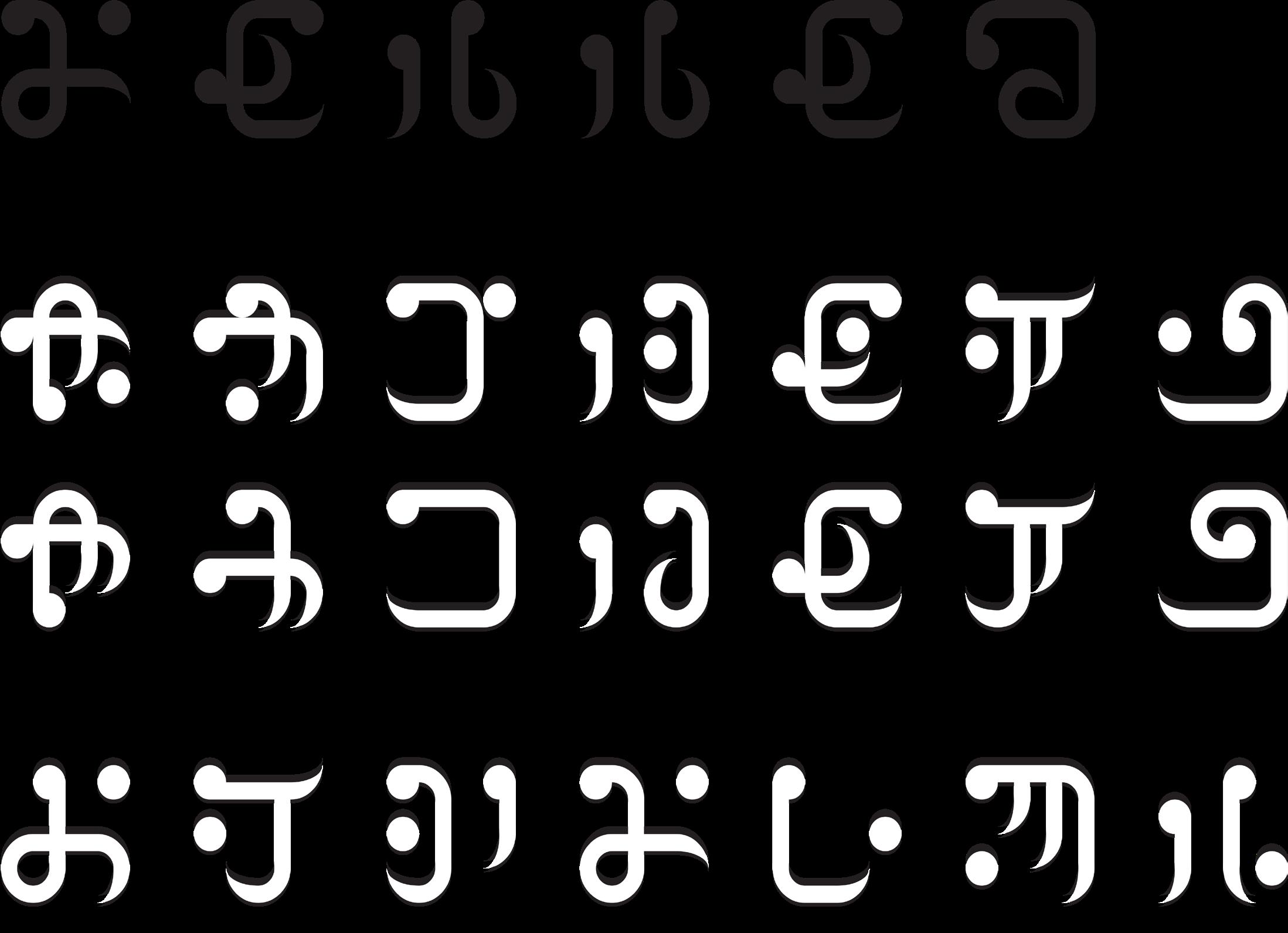

Zihan Li From Translation to Interpretation

Can we create a new contemporary graphic design style based on traditional Chinese elements in written language and typography?

How does culture affect its writing system, in both typography and visual communication?

How do the forms of letters and characters affect the function of languages?

In what ways do certain calligraphic strokes indicate the nationality of a typeface?

How can graphic design benefit from this hidden language, aside from written text that’s been typeset?

Languages can be seen as communication tools that have been sedimented through centuries. A written language, on the other hand, is a symbolic representation of communication. As someone who speaks both English and Chinese, I am capable of understanding their meanings without the need to translate from one to another. With this ability, I have explored questions relating to the relationship between language and culture, within the aspect of graphic design.

My research focuses on finding the deeper meanings behind the designed facade of written language, in practical methods that often experiment with legibility. How do the forms of letters and characters affect the function of languages? In what ways do certain calligraphic strokes indicate the nationality of a typeface? How can graphic design benefit from this hidden language, aside from written text that’s been typeset? With these questions in mind, I aim to uncover a new style of expression for contemporary design practice.

Toothbird is an experimental communication practice. The visual appearance resembles Fulu, a talisman about incarnations and symbols in Taoism, yet the symbolic and unreadable pictographs encourage an intuitive, open interpretation.

Kenneo: A type design using the Latin alphabet. Dots, lines, and tails are combined, on a pixel grid, to generate glyphs with a coherent graphic style. This produces a completely illegible, decorative typeface. With strong style and the resemblance of strokes, it creates a nonexistent language.

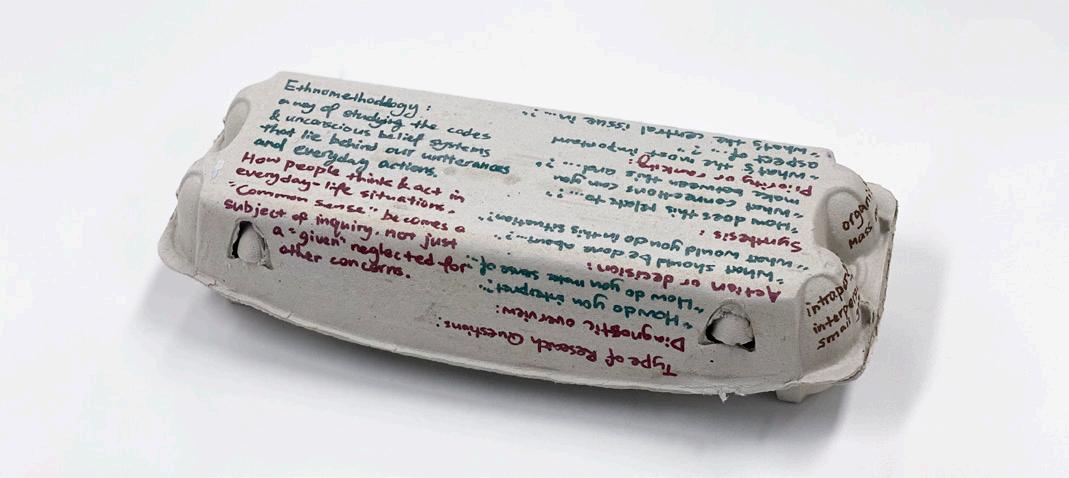

Zhiping (Sylvia) Xiao Form of Your Thoughts

What role might physical mind-mapping take in reconciling different viewpoints in order to reduce miscommunication?

Have you ever had the feeling of “how could he/she/they say that?” “How in the world could that person do that?” “How inhuman that person is!”

Yeah, why?

I am going to throw research on that.

The rough answer I’ve come up with so far is that people are similar to AI – trained by different databases. The databases of others stay unknown to us, which creates space for us to misinterpret others, leading to ‘errors’.

So, I wonder, could we unveil each one of our ‘databases’? How could we plot the contexts together so we can see each other and ourselves better in perspective?

What do your thoughts look like?

What’s in your mind? Fold and write down what’s in your mind.

And think: How are your thoughts related? What’s the context of each one of your thoughts? Pick one surface that you wrote context on; is there another surface whose stories caused the first thought? Is there any surface that can explain why you say this?

Does this format feel natural to you? What format would you feel more natural to you? What’s the shape of your thoughts?

If you can find another finished folding, try to place the two pieces in relation to each other. Are there any related thoughts?

You may add notes about your thoughts by attaching new material to the surfaces.

The form of my thought is three-dimensional. I found that writing on paper doesn’t feel natural to my way of thinking so I started to write on a box by my side and found that comfortable for me. Then I brought different shapes of boxes for my peers to choose and asked them to write what’s been on their mind recently on the box they pick.

While writing, my peers brought attention to how dynamic and flexibility of different surfaces affect reading sequence. For instance, the quality of privacy differences between insides and outside of the object (figure 1), how ‘breaking into’ the material enables carries a different type of energy for noting (figure 2), and opportunities of using notes as wearables and other display opportunities (figure 3).

After all the experiments with my peers, I also want to explore how my thoughts could connect with the form of the objects by myself.

Egg carriage has interesting typography (figure 6, 7). I can write in different orientations, across surfaces with the string of thoughts, and it makes the writing more interesting. It has a natural highlighting point which could also be used as a way to group thoughts. It also opens up a unique way to display notes.

Plastic bottle (figure 9) is transparent with complex surface transitions. It is like natural grids for me to write on. I can’t write on the inner side but it still creates interesting overlaying effects. Because there are so many orientation opportunities on a shape like a bottle, I could easily highlight things by changing the orientation (and with colour differences).

The sushi box (figure 10) has a bigger proportion of flat surface with natural grid on it for me to write something that’s visually formatted. I used it as a reminder. It’s also good for writing additional informations. The surface turnings create natural visual hierarchies. And I don’t feel anxious about approaching the margin when writing because each side can be continuous onto another side.

The earlier experiments mainly focused on how to plot each one of our thoughts onto different forms of surfaces, but how can different forms of thoughts speak to each other?

In my mind opinions come like arrows. They shoot toward the core of the topic from different directions and backgrounds. I first tried plotting out the discourse about my undergrad school (figure 13). Then I tried to plot out the different considerations of my current research question (figure 14). This model provides opportunites to reconcile different viewpoints. I am planning to explore more forms, spirals for example, as my next step to stitch together the form of your thoughts.

What unique information or emotions can be evoked by kinetic typography?

How can a symbol be designed to portray or envision London in the future using kinetic typography in immersive environments?

The immersive environment is a situation where the viewer is actually in the middle of an artificial world observing what is happening. The viewer uses all their senses to experience this virtual world. Immersive kinetic typography will be based on the visual representation of the text, combined with the technology and the wrap-around environment to create artworks that allow the viewer to interact emotionally and psychologically with the design and the surroundings. It is predominantly communicative, in comparison with media art which has the function of explicitly expressing art, humanities, and science.

From the 21st century, because of the development of the internet and various new media software, immersive interactive kinetic typography, as a new form of visual design expression, is finding the intersection of people’s communication and digital experience in a new environment. It is forming a new immersive and unique system of dynamic linguistic communication that refreshes the perception of communication. It creates a bridge that connects designers and audiences in a combination of different media and spaces. The viewer can become part of the artwork through their experience of the artistic process and can enhance the design concept and express profound connotations.

In order to broaden our understanding of this new language system and its impact, this project presents a study in which the author will create interactive kinetic typography in immersive environments, demonstrating that this can be used

to continuously convey the dynamic effects of information. I intend to create a research project that expresses a view of the characteristics of a future London environment, as well as a kinetic typography archive that expresses different messages about feelings.

I collected sound and video clips in London, and I found that the seven participants, my classmates, were largely consistent in their perceptive evaluation of the examples I provided. This ongoing project will analyse the audience’s desire for self-expression and emotional communication in kinetic typography by collecting their feedback on the work. It uses a combination of the meaning of the typeface itself and the expressive nature of typographic movement, and places it in a virtual immersive space. These different elements come together to form a unique project. The viewer can not only see with their eyes but can even feel the work with their senses and body, communicating with it in a way that can enhance the emotional quality of the viewer. The findings of this research provide design guidelines for the use of immersive environments to demonstrate the communication of information in kinetic typography.

This project was the starting point for my research on the direction of immersive kinetic typography. Last year, I explored the rhythmic movement of text in digital space using Chinese verbs as visual elements, and the project builds on how text can come alive with exaggerated movement as it changes shape and number. When my work was exhibited, the most frequently asked question was “Can your project interact with the audience?”. I realised that this topic can be carried on in further research studies.

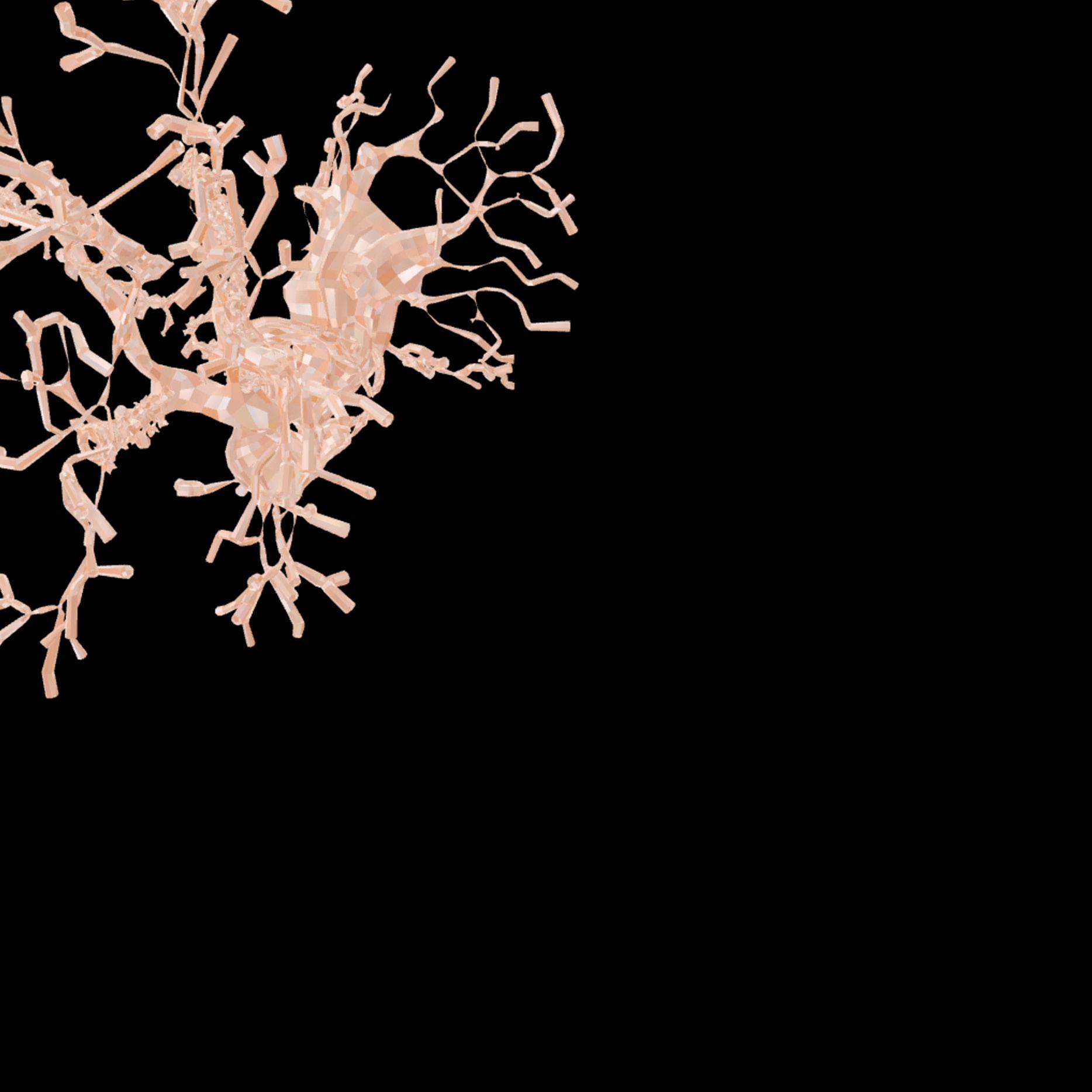

How can we become the body without organs in the anthropocene epoch? How do external sounds affect us?

Speculative design is a growing methodology raised by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby that objects to orthodox forecasting approaches, thus creating open debate about what kind of future people want. Speculative design could be a thought experiment and method to provide viable solutions and stimulate audiences to realise and discuss the ‘wicked problems’ – problems that are challenging or unattainable to solve (Dunne & Raby, 2013). Many speculative artworks deal with various techno-futures that reshape how people interact with resources and the environment – a task we may need to reset our imaginations in reaction to the Anthropocene, the latest historical era when human activities have significantly impacted the planet's environment and ecosystems. This phrase refers to an unofficial geologic time unit (National Geographic Society, 2022).

The research started with these keywords: speculative design, future, and interview and further expanded to the body without organs and applied sounds to investigate the complex interplay between Anthropocene and the future and the human body.

This practice-based research employs a standardised and open-ended interview method to participate in discussions about futures, bodies, and identities as the first step. Second, thematic analysis was utilised to gather data, analyse, and evaluate the results of the interviews. Thematic analysis is a helpful tool for resolving experiences, perspectives, or behaviours during data collection. The interview results led the investigation to a philosophical concept – the body without organs and Anthropocene. Raised by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, the body without organs means the body is uncontrolled and floating, opposing the dominant subject, and refusing to construct a central meaning. Sounds, especially experimental sounds, could be regarded as the body without organs since they are decentralised and fluid.

This research aims to provoke people to be aware of three major concerns in an artistic approach: what type of future people want, what the future might be, and how to react to it.

We as humans should examine ourselves under the context of the Anthropocene. We may need to rethink the consequences of our political and social structures on the earth (Anderson, 2015).

‘The Earth – the Deterritorialize, the Glacial, the giant Molecule – is a body without organs. This body without organs is permeated by unformed, unstable matters flow in all directions, free intensities or nomadic mad or transitory particles’ (Fast, 2018).

Deleuze and Guattari describe the earth as a body without organs, that the body is uncontrolled and floating, opposes the dominant subject, and refuses to construct a central meaning. At the same time, a body without organs is not a specific ‘body’; it can be anything that fulfils this requirement, such as a book that lacks a conventional narrative.

It is a response and backwash for the daily body under the current cultural system. Based upon this, the experimental sound can also be regarded as a body without organs since it has the following characteristics:

a) Sounds have the characteristic of vibration. Sound is a vibrating power that creates linkages between human and nonhuman bodies (Fast, 2018).

b) The hearer is fluid to the same degree as the sound object is fluid. The listener’s hearing, perspective, psychology, and culture shape the sound. Each person, community, and culture listen differently (Shank, 2020).

In some ways, we are as unpredictable and fluid as the body without organs. We as humans are endeavouring to figure out the position in nature, the relationship with technique, and the images of the other. However, in the physical world, we are restrained by the authority, power system and ‘the truth’, which means we are fettered. Likewise, capitalism and colonialism are closely correlated to the Anthropocene's consequences.

To break the centralisation system, we need to build a new ideology. Referring to the concept of ‘rhizomes’, raised by Deleuze, which means we need to create a diversified, mutability, irregularity, and fluid. When we believe we have touched freedom and unfettered metamorphosis, how can external voices affect us, whether we notice or not? Can we calmly confronted when the Anthropocene comes and be a

body without organs in a world supervised by systems and authority?

Ultimately, the artwork is an applied interview with the future body applied generative arts as a tool to explore the relationship between anthropocene, sounds and body (see below). A hybrid of a tree and a human backbone. The tree represents rhizomes – the metaphor and symbolism of the body without organs. The spine means human, both physically and spiritually. It moves, dances, and transforms vigorously or gently, affected by the random sounds of this world. This object seems to convert freely and uncontrollably, but it is controlled by the system, which is the code I put in. It moves based on the rhythm, pitch of the voice.

How does indeterminacy restructure our mechanisms of seeing the world, and how does randomness disempower the paradigms and ideologies that are imposed on us through visual lenses?

Communication is a set of tools that creates intermediary connections between humans and the world, but the mode of inputting and outputting information has already been formed by established rules according to the era. This project aims to renegotiate the order and sequence of a set structure through the lens of indeterminacy. By redesigning ways of seeing and communicating, it influences and reshapes the process of knowing.

How we understand/analyse human cognition is subject to certain conventions: most of us accept things that seem natural without awareness or questioning, we follow and then obey. How we perceive information is heavily influenced by the way we are taught to read and react. Roland Barthes talked about the power of representation in his book Mythologies, how objects and signs mean more than they seem. Barthes was concerned about how connotations (the implied aspect) become denotations, and he questioned how messages are understood through analysing social stereotypes.

John Cage incorporated chance composition in his music works. Certain elements in the composed work are left to be decided by the performer’s will, therefore the same work can be played in various versions. He defined it as ‘the ability of a piece to be performed in substantially different ways’ (Pritchett, 1993, p.108). Likewise, this ongoing project consists of a series of small experiments, and it starts with adapting randomness into an unconventional dialoguing. The experiments focus on

questioning and diverging on our common perception by employing an approach of selected choices.

Ulrich Baer once said, ‘blindness may offer an escape from the tyranny of the visual that overwhelms the poet’ (Baer, 2000, p.113) in his Remnants of Song. Similarly, we can understand blindness as directionless or indeterminacy – the blindness to authority, the blindness not as an inability to see but a refusal to look into the only direction that’s been given. The experiments in the project incorporate the idea of chance into the mechanism of seeing the world, they disarrange and rearrange the procedure of our interactions, which establishes new interpretations of already existing visual elements.

I am not designing an outcome, but instead a process that results in different outcomes. This project hopes to challenge common ideologies, and to subvert our ingrained conventions on absorbing and interpreting information, and to promote a change in behavioural habits.

Same set of stones are randomly arranged according to the lines on them therefore generate different outlines, shapes and patterns. Figure 1–3 belong to one group of stones and figure 4–8 belong to another.

There are two systems when playing this cube, the common one is with colours, but if player focuses on puzzling up the foreground letters, it naturally disrupts the rule from the regular system by the idea of indeterminacy.

In this mapping experiment, I am letting my music list guide me to a meandering path. The shuffle mode and length of the music will determine my route. I keep going straight until the song switches, then I make a turn at the upcoming intersection to the direction that is nearest to me, and I take a photo of that turning. Random selections bring new interpretations and perspectives.

What is the relationship between the language of light and expression of human emotions?

In this project my aim is to explore the relationship between the language of light and the expression of human emotions. My initial research was about the relationship between the human ideology of consumption and the added value of a product. In the course of my research, I interviewed and explored a product, in this case, a table lamp and found that my need for an object such as a table lamp is not only its lighting function but also its role as a listener to my stories half the time, which is an extra value given by my interpretation.

The objects in our surroundings are capable of carrying memories, feelings, and emotions, according to the approach of this research. At the same time, I am thinking about how a lamp responds or expresses its thoughts and emotions, how it becomes a storyteller or a responder to information. Talking to objects is a mode of emotional expression that people engage in to a greater or lesser extent, and even more so in people who live alone. In this process, I have tried to select a possible trajectory of light movement to describe the emotions the lamp might be trying to convey during the interview. This also includes an exploration of the rhythm of the light movement, the possibility of whether the colour of the light needs to be changed by the lamp or by its operator, and whether it should be accompanied by sound and other elements.

Light is an essential element for humans, and I think I will be looking more deeply into the relationship between light language and human emotions, possibly with experimental images or visualising the language of light. Light can present a very strong visual effect, and when the identity of light changes from being a listener to a storyteller, how do people reflect differently to such a strong visual language of light? The final presentation is intended to be an experiential design exhibition, where the language of light is experienced in a totally dark space, and I am also considering the healing effect of light in that total darkness, the different reflections of people and the rewards of people’s experiences in the space and atmosphere.

This is an experimental short film about an interview, in which I focus on exploring how does the lamp as an interviewee responds to my questions. It is a non-verbal exploration of what the language of objects looks like and is the beginning of my research interest. Here are some screenshots of the interview, where the lamp’s responses include flickering, shaking, focusing, scattering, and glitching.

Zijing Zhong The Journey is the Reward

How can graphic design be used to explore the model of story creations through texts and images?

The story is everything that people with different identities shaped in changing time and space. Their old and new identities, the inner world of the characters in stories, the psychological impact of experiences, and the fact that people with different identities will have diverse narratives. Centred on the story, related works in the subject areas of literature, painting, and film are valuable samples of those existing narratives as well as genre systems and representations. Furthermore, exploring people’s stories and discovering the philosophical or social meanings behind them that can be learned from the study of narrative.

It is vital to read the history and development of narrative, thinking about those appealing stories in literature, painting, and film, how all kinds of mediums were used by the storytellers, and finally looking at representations in contemporary times. Meanwhile, it is more important to discuss how people with different identities understand stories differently, and how the characters in stories can motivate people to understand themselves. Nothing is more fascinating than discovering people, especially the audiences, how they achieve communication between a character in the virtual world and their egos in the present through the stories in graphic design works.

The roots of different understandings of narrative could be family, education, age, gender, personal experience, and other possible factors. Therefore, the narratives may lead to the difference in many poeple’s understanding and impact. As an artist and designer, it is very worthwhile to establish connections between the audiences themselves and society through stories in graphic design works, and other developing artworks.

In addition, the story reflects on the relationship between itself and people’s worldviews through the lens of writer Robert McKee, provoking questions about whether genre systems and representations are a design language in graphic design, bringing this kind of design language to bear on the related creations of graphic design.

Finally, narrative has a great impact on people’s understanding of themselves. This may be a discoverable area related to the research questions on story. The project seeks to answer them by studying the stories, rewriting them, and creating new stories in the changing time and space, eventually using appropriate materials or mediums of narrative, in graphic design, finding philosophical connections.

L’Ingénu (figure 1), which is a fine art work created by Zijing, that has been moving forward at the RCA (figure 2). It continues to be relevant to the direction and keywords of Zijing’s research today. [A]MAZE has included its continued works, Bandages Experiments III: Tasting and Melting.

Between Worlds, an experimental graphic design work largely used texts and images that tells Zijing’s stories from his private social media (figure 3).

Can You See Her is an experimental work of text and image, made in collaboration with Garance Paule Querleu, it was shown by Zijing in a RCA MRes Across Pathway course (figure 4).

Get the Blossom I Have Ever Bleed (Huadao in Chinese), is a milestone of Zijing’s research and practice within graphic design (figure 5). His current research interests, such as texts and images, stories, and emotions, originated from this work.

Allium Cepa, a theoretical work centred on Zijing’s sketch book (figure 6).

Anderson, K., 2015. ‘Ethics, Ecology, and the Future: Art and Design Face the Anthropocene’. Leonardo, 48(4), pp. 338–347.

Auger, J., 2013. Speculative design: crafting the speculation, Digital Creativity, 24 (1), pp. 11–35.

Baer, U., 2000. Remnants of Song. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Barendregt, L. & Vaage, N. S., 2016. ‘Speculative Design as Thought Experiment’. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 7(3), pp. 374–402.

Beeghly, E., 2015. ‘What is a Stereotype? What is Stereotyping?’. Hypatia, 30 (4), pp. 675–691.

Berger, A. A., 2020. Media and Communication Research Methods: An Introduction to Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Braunmuller, A. R., 1997. ‘Macbeth’. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Burns, T. W., O’Connor, D. J. & Stocklmayer, S. M., 2003. ‘Science Communication: A Contemporary Definition’. Public Understanding of Science, 12, pp. 183–202.

Campbell, I., 2020. ‘Sound’s Matter: “Deleuzian Sound Studies” and the Problems of Sonic Materialism’. Contemporary Music Review, 39 (5), pp. 618–637.

Cox, C., 2020. How Do You Make Music a Body without Organs? Gilles Deleuze and Experimental Electronica [Excerpt]. [Online] Available at: https://www.heath.tw/nml-article/ christoph-cox-how-do-you-make-music-a-body-without-organs/?lang=en [Accessed 2022].

Des Jardins, J., 2010. The Madame Curie Complex: The Hidden History of Women in Science. New York: Feminist Press.

Dibley, B., 2014. ‘Nature is Us:’ the Anthropocene and species-being. Transformations Journal of Media & Culture, 21, pp. 1–23.

Dunne, A. & Raby, F., 2013. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction and Social Dreams Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Fast, H., Leppänen T. & Tiainen, M., 2018. Vibration. https://newmaterialism.eu/almanac/v/ vibration.html [Accessed 2022].

Hayles, K., 1999. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hoffman, D. D., 2016. ‘The Interface Theory of Perception’. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(3), pp. 157–161.

Jucan, M. S. & Jucan, C. N., 2014. The Power of Science Communication. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 149, pp. 461–466.

Kiger, M. E. & Varpio, L., 2020. ‘Thematic analysis of qualitative data’. Medical Teacher, 42(8).

Laird, P. W., 2007. Pull: Networking and Success since Benjamin Franklin. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Le Guin, U. K., 2004. The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination. s.l.: Shambhala Publications Inc.

Lees-Maffei, G., 2011. Writing Design: Words and Objects. London: Bloomsbury.

Leutrat, J. L., 2000. L'Année dernière à Marienbad. London: Bloomsbury.

Mascret, N. & Cury, F., 2015. ‘“I’m not scientifically gifted, I’m a girl”: implicit measures of gender-science stereotypes – preliminary evidence’. Educational studies, 41 (4), pp. 462–465.

McGuire, L., Mulvey, K. L., Goff, E., Irvin, M. J., Winterbottom, M., Fields, G. E., HartstoneRose, A., Rutland, A., 2020. STEM gender stereotypes from early childhood through adolescence at informal science centres. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 67, pp. 101–109.

McKee, R., 1997. ‘Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting’. Sivu: Structure and Genre, 4, pp. 79–88.

McManus, F. G., 2016. The genders of knowledge: analytic feminism, philosophy of science and scientific knowledge. Interdisciplina, 4 (8), pp. 59–87.

Mileck, J., 1981. Hermann Hesse: Life and Art. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Minick, S., & Jiao, P., 2010. Chinese graphic design in the Twentieth Century.London: Thames and Hudson.

Minsky, M., 1988. The Society of Mind. s.l.: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

Mithen, S., 2005. The Prehistory of the Mind: A Search for the Origins of Art, Religion and Science. London: Phoenix.

Müller, J., Rädle, R. & Reiterer H., 2016. ‘Virtual Objects as Spatial Cues in Collaborative Mixed Reality Environments’. Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 1245–1249.

Nakaya Pérez, M. I., 2021. ‘Between the natural and the constructed: an ontology of mental illness’. Mexico City: National Autonomous University of Mexico.

National Geographic Society, 2022. Anthropocene. [Online] Available at: https://education. nationalgeographic.org/resource/anthropocene [Accessed 15 October 2022].

Nichols, B., 1981. Ideology and the image: Social representation in the cinema and other media. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Nieto-Galan, A., 2011. ‘The audiences of science: experts and laymen through history’. Madrid: Fundación Jorge Juan Marcial Pons Historia.

Pauwels, L., 2006. ‘Introduction: the role of visual representation in the production of scientific reality’. Visual Cultures of Science: rethinking representational practices in knowledge building and science communication. Hanover: Dartmouth College Press, pp. vii–xix.

Pritchett, J., 1993. The Music of John Cage. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schiebinger, L., 1987. ‘ The History and Philosophy of Women in Science: A Review Essay’. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, pp. 305–332.

Shane, J., 2021. You Look like a Thing and I Love You: How Artificial Intelligence Works and Why It's Making the World a Weirder Place. s.l.: Brown and Company.

Shank, B. L., 2020. ‘Sound + Bodies in Community = Music’. JAAAS: Journal of the Austrian Association for American Studies, 1(2), pp. 177–189.

Smith, D., 2018. ‘What is the body without organs? Machine and organism in Deleuze and Guattari’. Continental Philosophy Review, 51(1), pp. 95–110 .

Spidell, K. et al., 2004. Baby Human. [Film] Canada: Ellis Entertainment.

Tang, A., 2018. Made in Japan awe-inspiring graphics from Japan Today. Hong Kong: Victionary.

The Royal Society (RS), 2022. The Royal Society. [Online] Available at: https://royalsociety. org [Accessed September 2022].

Turrell, J., 2023. Dark Spaces. [Online] Available at: https://jamesturrell.com/work/type/darkspace/ [Accessed January 2023].

Tynan, A., 2022. The Howl of the Earth: on ‘the geology of morals’, nihilism, and the Anthropocene. Angelaki, 27(5), pp. 3–16.

Valenzuela, D., & Shrivastava, P., 2002. Interview as a Method for Qualitative Research. [Online] Available at: https://www.public.asu.edu/~kroel/www500/Interview%20Fri.pdf [Accessed 2022].

Van Der Pol, J., & Laganier, V., 2011. ‘Light and Emotions: Exploring Lighting Cultures’. Conversations with Lighting Designers. Basilea: Birkhäuser.

Voegelin, S., 2010. Listening to Noise and Silence: Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art. New York: Continuum.

Wragge-Morley, A., 2020. Aesthetic Science: Representing Nature in the Royal Society of London, 1650–1720. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Xu, B., 1987-1991. Book from the sky. [Art].

Xu, B., 1987-1991. Square Word Calligraphy. [Art].

Labna Fernandez is a Mexican biologist, who graduated from Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico in 2022 with a final project about molecular microbiology. She is interested in the history of how science has been publicly communicated. She has presented several science communication projects both nationally (in Mexico City and Durango) and internationally (in Luxembourg). Labna has a strong social commitment, which informs her research. Her current research interests are in the gender bias in how scientific narratives are constructed and the effects of this on female representation in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) subjects. For her master’s degree, the Royal Society is her research focus and involves exploring how it has publicised itself and uncovering its bias mechanisms.

A practising graphic designer, Zihan Li grew up in China and took professional graphic design training at the University of Utah in the United States. His cross-cultural experience has shaped his identity, in the forms of both verbal and visual languages. He is deeply interested in the historically rich Chinese culture, yet appreciates the contemporary artistic styles commonly seen in the western world.

His research focuses on visual communication and culture, especially in typography and symbolism. Currently, his research goal is to discover a new style of expression in graphic design based on traditional Chinese elements.

Sylvia (Zhiping) Xiao wonders about the world. She wonders how the world functions in general. She wonders about how things come to exist and why they don’t. Specifically, she is interested in how we misunderstand each other. To understand how people make decisions and what creates our daily physical life, Sylvia studied Product Design and graduated as the valedictorian at Art Center College of Design in California for her bachelor’s degree. With all her making and designing skills, as well as an overview of the industrial product world that she acquired there, Sylvia is now expanding into a more abstract and theoretical realm.

Lifei Shan is a graphic designer, and her study project focuses on the impact of kinetic typography design on audiences at RCA. Between 2018–21, Lifei was a postgraduate student at Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts, with a research focus on the theory and research of font design. During this period, she participated in a National Teaching Research Project – Zhihuishu Mooc-Font Design in 2019. She also created an animated text design on Chinese verbs, focusing on rhythm, and wrote an article, ‘The Visual Rhythm of Animated Text’ (Tianjin, 2021) based on the project. She is currently creating kinetic typography and working on the topic of the emotional communication of interactive kinetic typography on audiences in immersive environments.

Yixin Zhang is an observer and a designer who previously studied social sciences, fine arts, and art histories during her undergraduate period in Canada, and is currently practising in design. This diverse academic background has naturally led her to an interdisciplinary making journey, and she is working across visual communication design, photography, sculpture, installation, and video.

The enduring questions in the field of communication design fascinate her. In particular, the curiosity of how communication as a tool shapes and is shaped by humans, has informed her research interest in the exploration of how to overthrow the conventions structured through the means of visual persuasion.

Fan Zhang is an artist, designer and researcher who was born in China in 2000, currently based in London. Before she joined the RCA MRes Communication Design, Fan Zhang completed her foundation and the first year of her bachelor's degree at Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, Australia, in 2018. She then moved to London and completed her bachelor’s degree in Graphic and Media Design at the London College of Communication, University of the Arts London, in 2022. During this time, she became increasingly curious about speculative design, sounds, philosophy, and generative arts, which provided her with considerable inspiration for creation. Multicultural shocks and life experiences in foreign countries enliven her investigation of communication by using interdisciplinary methods.

Zhenyi Wei is a communication designer who graduated from Jiangnan University in China with her undergraduate studies in visual communication design as her main field of study. Based on her interest in communication design, she researches into the ways that humans express and respond to emotions, as well as the psychological healing effects of the language of light on people. Her current research focuses on light and its effect on the psychic level of people; in other words, how light interacts with people and the resulting expressions by the light, tentatively defined as the ‘language of light’. In her master’s programme, she continues to explore the possibilities of the language of light and how it functions, how it can help people living alone in particular to express and release their emotions and the role changes of light can play in the narrative process in forms of experimental film.

Zijing Zhong currently is an artist and designer. Born and raised in China, Zijing discovered a passion for art and design while living in Hangzhou, a city which is considered to be an art paradise in China. Here he appreciates the stunning views of West Lake, studied art at the China Academy of Art (CAA), and gained unlimited power of creating things. He used to explore industrial design, then took himself on a long journey from graphic design to narrative research. He believes in the significance of the stories behind all kinds of works, such as the Tetrad in 2022, and in the works designed for the World Earth Day every year since 2016. Prior to those works, he was welcomed in designing University of Nottingham Ningbo China (UNNC)’s products for new students in 2019 and updated his designs in 2020. He also worked as a collaborative artist at Bilibili and was invited to create Bilibili’s visual art works and daily updates. Zijing has also held other roles including lyricist, composer, arranger, electronic music artist, studio founder, photographer, and Apple developer.