FEATURING...

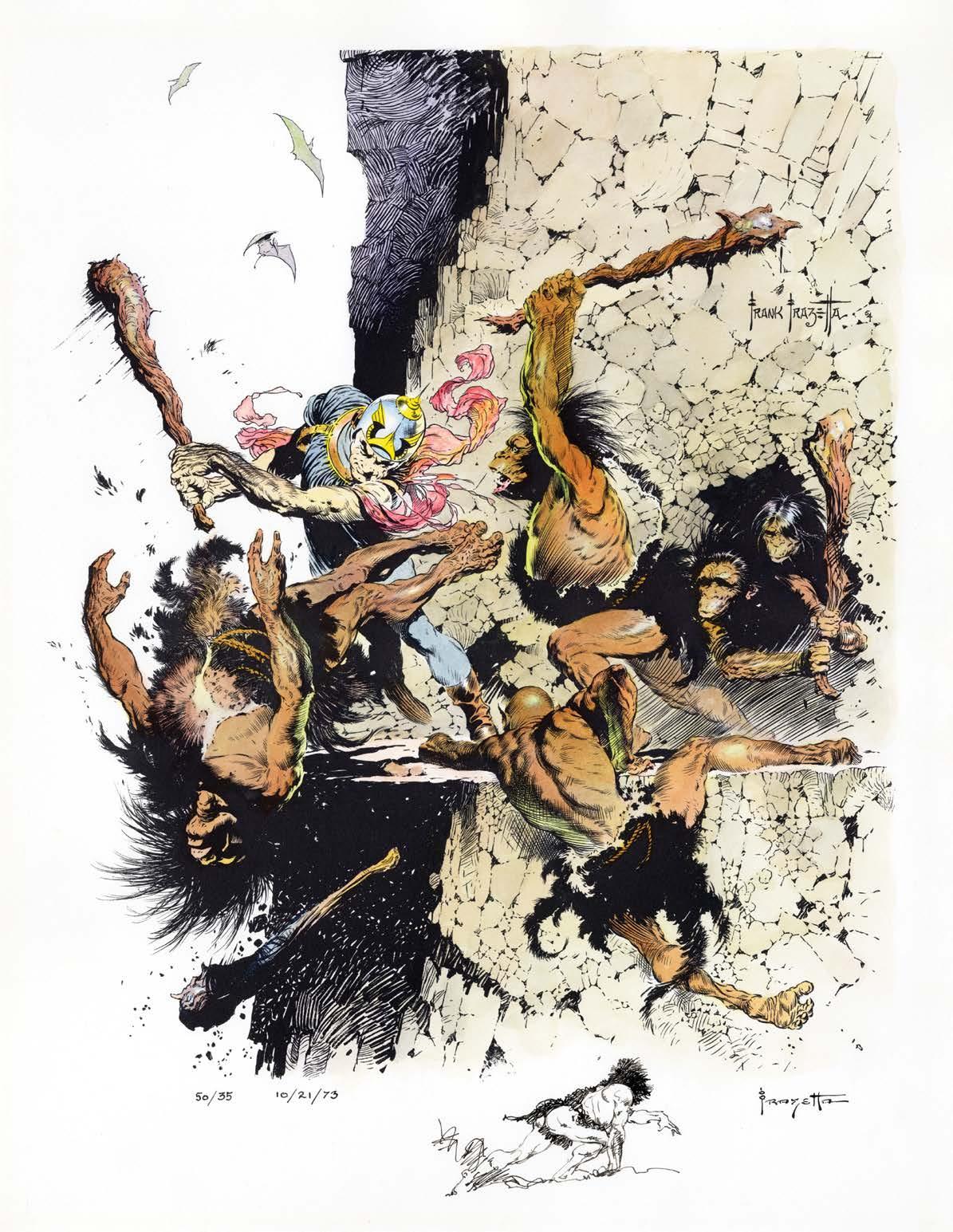

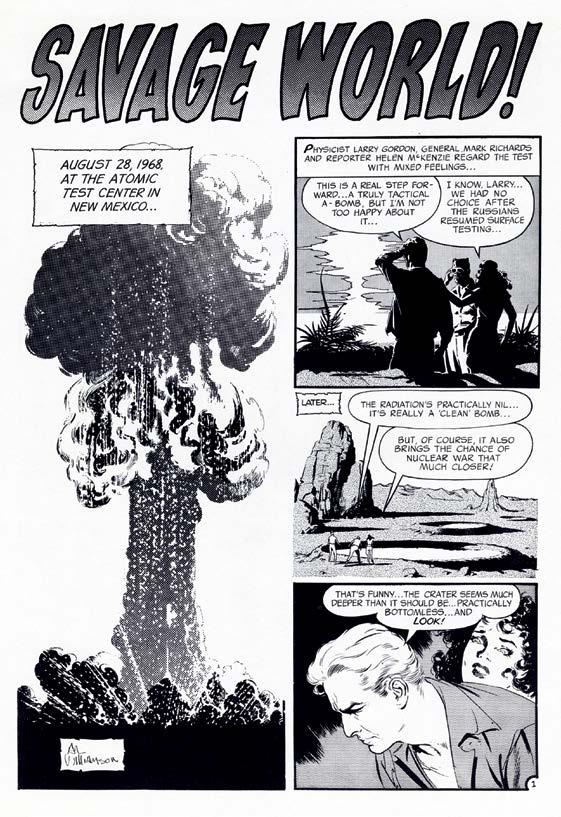

In EC Fan-Addict Fanzine No. 2 (December 2012) my article “The Savage World of Buster Crabbe” revealed information about a very muddy-looking, hand-colored silverprint discovered in the flat files of artist Al Williamson during a visit by Mark Schultz and myself in 2008. This startling revelation was a surprise to Mark and I, as it was other Fleagle collectors after we published the image for the first time. The cover tied in with an eight-page story titled “Savage World,” which for many years also laid in Al Williamson’s flat files, unpublished. Fans first became aware of it in 1966 when Wally Wood published it in Witzend No. 1. Though Wood offered no explanation as to the origin of the story, historians eventually learned the job was produced in 1954 by Al Williamson, Angelo Torres, Roy Krenkel and Frank Frazetta for a Lev Gleason comic book titled The Amazing Adventures of Buster Crabbe. Eastern Color/Famous Funnies had been responsible for publishing the first Buster Crabbe comic book, consisting of 12 issues dated between November of 1951 to September of 1953. Some of the artwork on that title was supplied by Frazetta, Krenkel, Williamson, George Evans and others. After being cancelled, the comic was picked-up by Lev Gleason with a title change to The Amazing Adventures of Buster Crabbe, starting over with a first issue dated December 1953, and trumpeting Buster Crabbe as “The All American Hero” on every cover. For the four issues published between December, 1953 to June, 1954, artists such as Alex Toth, George Tuska, Mike Peppe, Mort Leav, Pete Morisi, Rocky Mastroserio, and Vic Carrabotta were utilized.

Al Williamson became involved with this title sometime in early 1954. One wonders how and why Williamson got involved with the project at such a late date, although it’s likely that Al, being the huge Buster Crabbe fan he was, had followed the Lev Gleason title, and was not happy with the way it was being handled. As Williamson recalled in an interview conducted by James Van Hise in his 1983 book The Art of Al Williamson:

“That was for another outfit that started doing Buster Crabbe comics, and as far as I recall, the first issue they did was by Alex Toth. Anyway, I went up and got a sciencefiction Buster Crabbe story to do that was eight pages long. But they went out of business before they actually printed the book, and there I was without any money and without the originals. Four of us worked on that: Angelo, Roy, Frank, and I. I remember that I had the money and I remember that I was able to pay Roy and I was able to pay Frank for the work that they did on it, but Angelo and I did the bulk of it and I didn’t have the money to pay him. We got a letter from the company saying please meet us at such-and-such office where we will discuss what we owe you and so forth. We went over there with a bunch of other artists. I think George Tuska was there, and we waited around and I said to Ange, ‘You know, I’d rather have the originals back than the money, because they’re not going to give us the full payment of $30 a page; they’ll give us a token amount and that’s it.’ And he agreed that we should

by Roger Hill

get the originals back. So when we were called in to get the money, I just said, ‘Well listen, we’d just as soon have the originals back. You don’t have to pay us.’ And those businessmen all looked at each other like we were nuts. Businessmen just don’t understand. They have no souls, those people. And they said, sure, we could get them back, but it took three or four weeks to get them back.”

Williamson had held onto the original art to the story for many years and eventually let Wood rename it as “Savage World,” when Wood published it. The original title may be lost to the ages at this point. He had never mentioned that a cover silverprint, color prelim,

Above: Future juvenile delinquents reading crime and horror comics in this cartoon from the January 18, 1955 issue of the Christian Science Monitor

Wertham: You can’t distinguish it. When you see a child who tells me all these fantastic stories it’s difficult to tell whether he got it from a comic book or television show.

Burke: Alright young man, your name please?

Marvin Wolfman: Marvin Wolfman. I happen to be a comic fan right now. I have been reading comic books since I was five. I’m 21 right now. I’m going to college, and I also happen to publish a fan magazine on comic books. My main question, among others, is that in your book Seduction of the Innocent, which was written, I believe, in 1954. I read it twice, I didn’t believe it the first time! You happen to be interviewing constantly many children and going through their backgrounds, and in every case, they have either been from broken homes, are not mentally well, or the family structure is poor. From there, you show the fact that they happen to read comics. At the same time, you mention that their reading level was low and usually it’s five or six years behind the supposedly normal reading level. Yet you are basing these findings on the fact that these children were from deprived homes. And from this, you judge that because they read comic books, they are like they are. They’re juvenile delinquents because they read comic books, rather than

the fact that you met them because they were juvenile delinquents. You don’t speak of anyone in your book that came from a normal household. I would like to find out how you can base your reasoning on only meeting one type of person, or only one segment of the population?

Wertham: You are completely wrong in what you say. You’d better read my book once more. First of all, I don’t only see children who come from deprived homes, not at all. I work in clinics, I see them privately. I’ve done research on whole schools. I’ve taken whole school classes and then there’s no question of broken homes at all. Secondly, I never said that reading a comic book makes one delinquent. You see, I’m a doctor. I have to take into account all things that cause things. When I see someone in trouble, I have to take up all different factors that enter into that. I found out that there were comic books that no one paid attention to. It depends on the individual which factor is more important and which is less important. That’s sometimes very difficult to decide. Anything may throw somebody off so it isn’t that I see a special class of people. I’ve never said it causes it. I’ve always carefully said that it’s a contributing factor to many children’s troubles. And this is one

Marie Severin was the colorist for the lion’s share of E.C.’s New Trend output, having joined the E.C. staff in 1951 at the recommendation of her brother John. Gaines and Feldstein affectionately referred to her as “E.C.’s conscience,” because if she thought a particular panel was too gory, she would color it entirely in a single color, like blue or yellow, in an effort to tone down the gore. Feldstein said that “She was a top-notch colorist. You have to give Marie Severin credit for selling a lot of the covers that were done in black and white, but were really brought to life by her color.” When E.C. stopped publishing comics at the end of 1955 (the final E.C. comic was Incredible Science Fiction No. 33, cover-dated January–February 1956, but on the newsstands about two months before that), Marie found work with Stan Lee at Atlas (later called Marvel). After the infamous “Atlas implosion” in 1957, which resulted in many artists and staff being let go, Marie went to work for the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. While there, she drew various educational illustrations for them. In an interview with Katherine

Keller at 2001 San Diego Comic Con (published online in Sequential Tart, May 2002), Marie said “I then worked for the Federal Reserve Bank. A friend of mine had a job there. I did a little bit of everything for them. I did television graphics on economics, which was a real challenge. I did a lot of drawing. I did a comic book that my brother did the finished art on. It was about checks, you know when they were beginning the little numbers on the bottom of them, for when they ran it through the machines.” (This collaboration with John Severin was called The Story of Checks, and was first printed in September 1958. It went through a number of printings, remaining in print at least through 1987.)

Through her association with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Marie illustrated a number of programs for the Financial Follies, which were a series of yearly events then held at the Hotel Astor for the New York Financial Writers’ Association. Apart from a lovely dinner, the festivities would include humorous musical revues written and performed by financial writers for such august