26 minute read

Dairying through the years

from Dairy Farmer February 2021

by AgriHQ

Seeing Canterbury dairy farming go from a handful of conversions to land-use dominant.

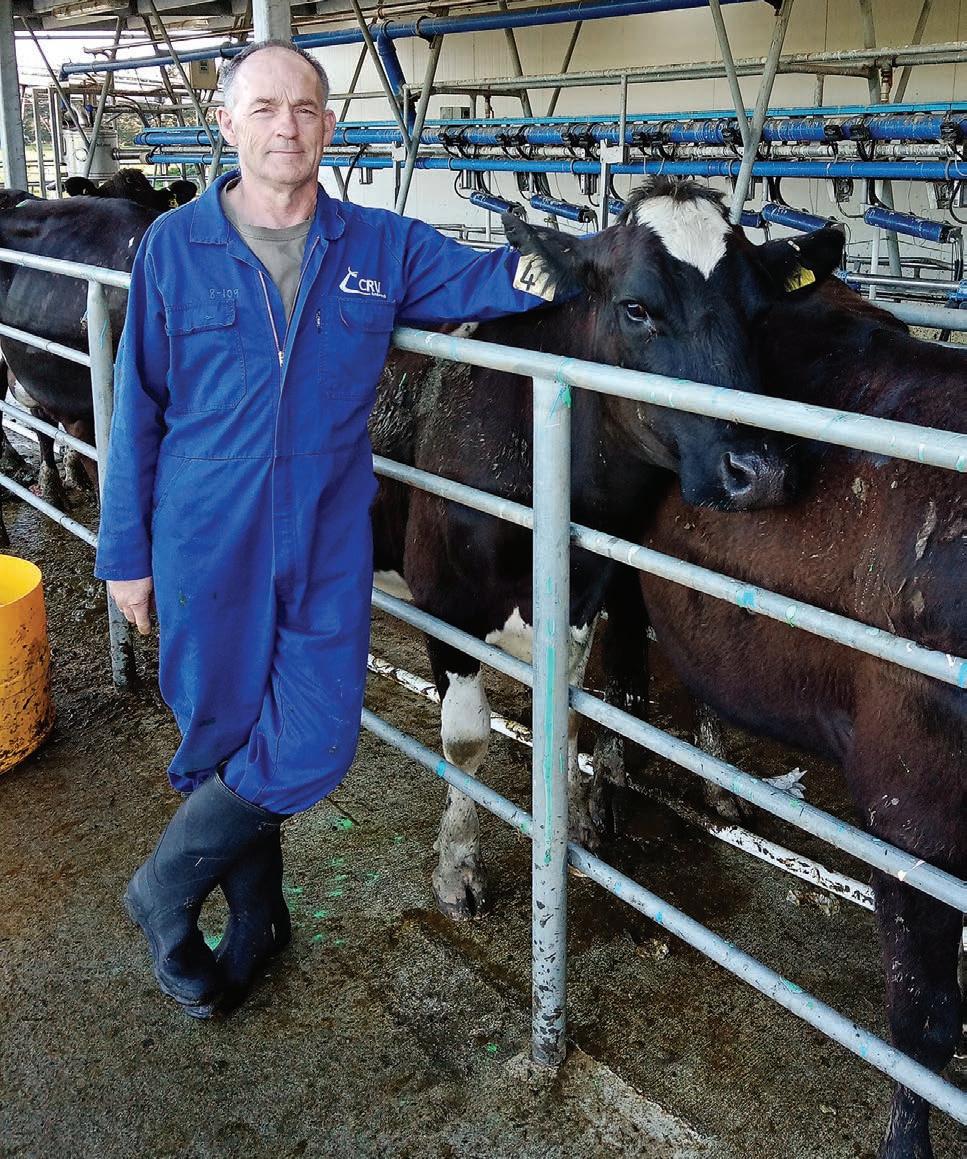

Coming from a long line of farmers, US-born and now Canterbury-based Marv Pangborn’s life did a complete 180 when he traded his office job to go sharemilking three decades ago, and got to witness first-hand how dairy farming boomed over the years.

When Marv Pangborn turned his back on a banking career in the US in favour of a sharemilking job in Canterbury in 1987, it was during a time where dairy farming in the region played second fiddle to sheep, beef and cropping. But, in his nearly 33 years here, he’s seen the farming focus shift sharply to dairying.

Today Oregon-born Marv and his Kiwi wife Jane live near Rakaia on one of the two dairy farms they converted on what had previously been undeveloped, dryland on the north side of Rakaia River. Their daughter Lauren and son-in-law Liam Kelly are 50:50 sharemilkers on one of the properties and contract milk the other.

Marv was born with dairy farming in his blood, descended from a line of farmers that goes back to the earliest days of European settlement of America.

“They can trace back my male line nine generations,” Marv says.

“The first guy got off the boat in 1664 in New York and we’ve all been farmers since but I ended up down here (in New Zealand).”

Marv got his first taste of Canterbury in 1975 when he took advantage of an exchange programme between Oregon State and Lincoln universities. He met Jane and after he returned home to finish his degree, she went to Oregon on exchange. They married two years later.

Marv worked for a bank as a rural lender for eight years and he and Jane had two children, but she missed home and he didn’t see a future in banking. Then out of the blue an offer came to go sharemilking in Canterbury. The timing was perfect.

A good friend, dairy farmer Jim Geddes, who Marv worked for when he was at Lincoln, recommended him to an investor who was having trouble finding a sharemilker.

“He’d bought two dairy farms that had been converted, some of the first conversions in Canterbury, with border dykes. He financed the first year at 12% (to buy the cows) when the banks wouldn’t even touch us,” Marv recalls.

By today’s standards, 12% interest sounds high but in the late 1980s that was half the going rate and gave them the opportunity to get into dairy farming, but, even so, with the payout at around $3.65/kg MS, there wasn’t much to come and go on.

They bought the herd on the farm for $400/cow and after sharemilking for a couple of years, the owner sold the farm to early Canterbury corporate farming enterprise Applefields, which turned out to be another opportunity for them as Applefields purchased the cows for $650.

The Pangborns bought 80ha of undeveloped dryland on lease from Environment Canterbury (ECan), built a house and he worked for Wrightsons and

Continued page 22

FARM FACTS

• Owner: Pangborn Family Trust • Location: Bankside, Canterbury • Farm Size: Farm 1: 190ha effective, farm 2: 145ha effective • Cows: Kiwi cross, Farm 1: peak milk 660, Farm 2: peak milk 520 • Production: 2019-20: Farm 1: 346,705 kg MS, Farm 2: 263,433 kg MS • Target: 2020-21 kg

MS similar to 2019-20

The 1180 Kiwicross cows on the two farms produced a total of 610,138 kilograms of milksolids in the 2019-20 season.

then US semen supplier Worldwide Sires for a couple of years, while Jane and the kids reared calves.

The farm did have a water right consent, but only limited irrigation was in place so in 1991 they border-dyked the rest of it and in 1993 converted the farm to milk cows. While the shed was still under construction, the farm next door came on the market. It was an opportunity too good to miss even if it meant borrowing what seemed like a huge amount of money.

“We had some money, but needed more,” Marv says, adding that their first application to borrow the money was turned down.

“They said there’s no future in dairy farming in Canterbury.”

The next bank he talked to had more foresight and lent them the $250,000 they needed.

“We bought 250ha, sold 100ha off to a developer who put it in five 20ha blocks and that meant we got our 150ha really cheap,” he says.

In their first season they milked 125 cows and increased the herd to 450 over the next four years. The 170ha farm was irrigated by border dyke and K-Line with water from the nearby Rakaia River, but in 1995 they put in a well to supplement their supply. The farm now runs 670 cows.

In 2005 they bought one of the last dryland undeveloped farms in their district and converted it in 2009, and today 510 cows are milked on the 140ha property.

In the 2019 season, the herd on Farm 1 produced 346,705 kilograms of milksolids and on Farm 2, produced 263,433 kg MS.

In addition to grass, the cows get 700-800kg supplementary feed during milking, comprising (depending on the price at the time) barley, PKE, silage, prolick and fodder beet.

The fodder beet is principally used near the end of the season and anything left over is fed in winter. Fodder beet is also used as a break crop in the regrassing programme.

In 2014 they bought a block in Southbridge to serve as a runoff. He is not convinced having the runoff adds up financially, but one advantage is that it makes their operation self-contained, which meant they were able to get through the M. bovis crisis without any trouble and can make most of their own supplementary feed.

About the time they were developing their second dairy farm, he had the first inkling that the restriction-free way dairy farming was booming in Canterbury, might not last.

“I was talking to a neighbour and he said, ‘Have you talked to ECan about nitrogen?’ and I said ‘What are you talking about?’, because I’d never heard about it being a problem,” he recalls.

But within a short time, new limits to protect the environment were signalled as alarm grew in the community about the effects of large parts of Canterbury being converted to dairy farming.

With inefficient border dyke irrigation on the farm, they needed plenty of water to keep their pastures growing but just how big a problem this was, didn’t really dawn on him until he took the time to think about the whole farming operation, its future and the issues it faced.

And he didn’t get time to do that until he got out of the shed and took on some sharemilkers.

“I was overweight and thought now that I don’t have to milk cows every day I’m going to get even heavier, I should do something, so I started walking. For the first time in 10 or 12 years I had time to actually think,” he says.

“I also started teaching farm management at Lincoln University, so I

The Pangborns converted and developed two drystock properties into dairy farms, milking a total of 1180 cows.

was exposed to many different ideas,” he says.

“While I walked I thought about farming and thought this isn’t going to last. We had this massive water right because we needed it because border dykes used so much water.

“We started by measuring how much we were using and learned we had a problem. “ECan was talking then about putting flowmeters in and once they did that, our border dykes wouldn’t work. It was a case of ‘eventually they’re going to wake up to this’.”

In the years since that realisation all the border dyke and K-Line irrigation has gradually been replaced by centre pivots backed up by soil moisture sensors to ensure only the required amount of water is applied.

Making the changes has cost nearly $2 million, comprising $1.5m for five centre pivots, fixed grid systems and a water storage dam, $33,000 for soil moisture monitors, $175,000 for effluent storage and spreading, and $180,000 for the removal of trees, new tracks and new fencing.

He believes the issue of water quantity has largely been addressed thanks to changes farmers like him have made, along with water metering and restrictions on how much can now be drawn from wells, but the issue of nitrogen leaching is far from being resolved.

“For a long time we denied environmental issues and I’m sure a lot of people would still deny it’s an issue,” he says.

“‘The river’s always been like that’, they say.

“The problem is even if we didn’t accept it, we had to deal with it. I’m not an environmentalist by any means but I am a business person and just like other businesses we have to face compliance whether it is environmental or other issues like health and safety.

“They (ECan) said, ‘You’re going to have to get consents to farm’, which we’ve never had before, ‘and prepare farm environment plans and those plans will have to be audited’.

“So, we moved into a whole new realm of things and I think even for me it was like the five stages of grief – denial, anger, bargaining, and depression until you get to the point where you just accept it.”

Under the Canterbury Water Management Strategy, the Selwyn Waihora catchment where the Pangborns live was the second of 10 zones in the region where committees comprising farmers, environmentalists,

Continued page 24

TALK TO THE EXPERTS FOR FARMING SUPPORT

07 858 4233

farmservices.nz

info@farmservices.nz

iwi representatives and other stakeholders hammered out policies and set environmental limits, which have since been put in place.

“I think the story of those of us in these areas is probably good for the rest of New Zealand because from the human psychological point of view, how do you deal with these things – there’s a bit of a story there,” he says.

Marv says there was grief – they’re taking away our way of life – and there was anger.

But he says through it all, most farmers worked their way through the stages and came up with plans that allowed most of them to meet the targets.

“We were partially into managing water quality due to the quantity thing. Quite frankly, the thing that improved nitrogen (N) leaching the most is infrastructure, efficient watering systems,” he says.

That development is continuing and today his daughter Lauren and her husband Liam are looking to further improve production, while confronting a new raft of environmental regulations and limits.

“Once I started owning my own herd and doing this stuff, that’s when the real passion kicked in,” says Liam.

“Prior to that when you’re managing you don’t understand because you don’t have that skin in the game.”

Born and bred on a dairy farm near Dannevirke, Liam worked for eight years on farms near home before coming to the South Island “for a look.” He met Lauren and the couple were considering taking a sharemilking job back in Hawke’s Bay.

“We were going to buy the herd so we said to Marv and Jane, ‘If we do this we’ll be here for a long time, so if you want us to come home, you’ve got to create that opportunity’.” Liam says.

“It turned out well,” Marv adds.

“Because he was coming, it drove a few things like building a new shed, which was good because it was needed and he pushed some of the development ahead.”

A new challenge for Liam is the rule capping N application at 190kg/ha.

“We can do 190kg but 150kg will be hard — 220kg would have been easier,” he says.

Along with greenhouse gases, the limits to N use have them both searching for answers. They are working to improve the genetic quality of their herd as well as regrassing with new species more often than they used to.

“Regrassing, despite the cost, is still cheaper than buying feed. We in NZ can grow grass better than anyone in the world, nobody else can do what we do,” Marv says.

They also soil test every paddock compared with the five or six they used to test and apply fertiliser accordingly. safety.”

The easiest way to reduce greenhouse gases is by reducing cow numbers, but they don’t want to reduce profitability, so they’re looking for genetic solutions.

Liam says to do that it’s crucial to be absolutely sure which calf came from which parents, but he believes NZ farmers get that wrong at least 30% of the time, either because of record-taking mistakes or cows which have mixed up their calves before they’re picked up.

“We want to get as close as we can to 100% so we DNA test to confirm Team member James Quinones hosing

down the yards after milking. which cow a calf has come out of and to confirm the sire,” Liam says.

He says they also now take both morning and afternoon samples when they do the four-times-a-year herd tests.

“I think we went from 65% to 95% reliability doing that,” he says.

It’s more accurate than the calculated Marv Pangborn estimate with morning testing, so now we’re dealing with the true facts.”

No bulls are used over the herds, which are all put to AI to produce valuable replacement calves.

“Liam has a really intensive mating programme and the calves arrive very quickly,” Marv says.

“He works really hard, makes sure the cows are in good condition and gets good results.”

Sharemilker Liam Kelly in the fodder beet paddock, which is fed towards the end of the season and in winter.

His six-week in-calf rate is 79% on Farm 1 and 77% on Farm 2, well above the national average.

For the past few years they’ve been using semen from LIC’s A2 genomic team bulls, which is cheaper than semen from older, proven bulls, which covers the cost of the DNA testing.

“The reliability is quite strong because nine out of 10 are pretty good,” Liam says.

“For us it’s all about being as close as we can get to 100% recording, but also real strong measurement of their performance and we have discussed weighing the animals to find the most efficient animals.

“You might have a big Friesian and then a crossbreed and one might be 550kg and one might be 500kg but it’s producing more milk. So, once we’ve weighed them and put that data against the cow you get more reliability with your BW and PW.”

They use sexed semen with some cows to help speed up genetic improvement and AB the heifers.

“The best genetic gain is to AB your heifers because they’re your youngest animals with generally the highest genetics,” Liam says.

“The heifers are coming through with really high BWs because of the most

current genetics and you can match that by using sexed semen with the best cows, so the genetic selection pressure he’s putting on is really high,” Marv adds.

Liam only breeds from their top 60% of cows and the rest are inseminated with Wagyu semen. The resulting calves are contracted to finishers with heifers and bulls fetching the same price.

“A lot of people have used beef bulls but some guys couldn’t get rid of their Herefords. I know a few friends who were selling them to lifestyle guys, but with the Wagyu it’s all contracted,” Liam says.

In his more than three decades of farming here, Marv has seen dairy farming in Canterbury go from a handful of conversions to become the dominant agricultural land use, at least on the flat land.

“I thought it was a better place for the kids to grow up than the US and it just happened – I’d always wanted to be a dairy farmer, I didn’t want to retire as a banker,” he says.

“We have been really lucky. It was the old story of ‘when you paint yourself into a corner, sometimes you get pretty innovative,’ and I painted myself into a corner quite frequently. Everything worked which is amazing.” n

Half a million babies

By Gerard Hutching

A Southland artificial breeding technician has notched up a milestone 500,000 inseminations in New Zealand and Holland.

Artificial Breeding (AB) technician Dirk van de Ven has an enviable lifestyle.

For about three months of the year the Winton, Southland, man works as an AB technician, earning enough to see him and wife Mieke through the year, albeit with odd jobs supplementing his main income.

“Then I do a little hoof trimming, gardening, walks, get firewood – it all keeps me fit. We work very hard for three months, then do a few little jobs,” Dirk says.

Now 60, Dirk hails from Holland, from where he shifted permanently in 2012. Over a 40-year career, he estimates he has inseminated half a million cows. He has been named the 2019 CRV Ambreed AB Technician of the Year for the Southland region.

The award recognises his commitment, competency and excellent cow return rates, meaning his success at ensuring cows are in calf.

In New Zealand, professionally trained AB technicians do the majority of inseminations. They are responsible for the handling and insemination of semen. CRV has more than 200 technicians across the country.

An AB technician must understand animal anatomy to ensure correct placement of semen in the cow’s reproductive tract. The job demands skillful handling to ensure the safety and Dirk van de Ven was named the 2019 CRV Ambreed AB Technician of the Year for wellbeing of both the animal and the the Southland region. In his 40-year career, he estimates he has inseminated half a inseminator. million cows.

Dirk describes the conditions and pay of the job as “very good.” In 2020 he managed to inseminate 11,000 cows, stressful, which it can do when you’re we went back to Holland where we did making what he describes as “a good working long hours during the peak of the same work, or at least I did, because income.” It was his busiest year ever. But the season.” Mieke was a nurse,” Dirk says. he cautions that he is not a one-man (or Before he and Mieke emigrated to NZ, In 2012 the couple decided to make the person) band as wife Mieke helps to load they used to travel from Holland every move a permanent one. Their three sons the pistolets, drives the car and does the October (starting in 2008) to work for were all pursuing successful professional administration. CRV during the NZ AB season, which careers – none related to farming –

He credits Mieke for his success, saying back then typically lasted six to eight and they felt NZ offered an attractive he couldn’t do his job without her. weeks. opportunity, both in work and lifestyle.

“She handles all the paperwork, she “I came for four years in a row from Dirk first trained with CRV’s drives me, she makes us food and she 2008 for the first time, starting the end predecessor company in Holland as a helps me cool my heels when it gets of October and ending December. Then 19-year-old. He grew up on the small

farm his parents owned where they ran chickens and cows, but it was too small to provide a satisfactory return. The exception was when they raised chickens for meat.

“In Holland when I realised I wouldn’t be taking over the family farm, I decided to do the next best thing and learn how to breed good cows.

“I learnt to do that with CRV and I have been with them ever since. I trained as a technician when I left school and I got a job and got into it.

In Holland an AB tech works every day of the year, whereas over here it’s seasonal, starting the end of October

Continued page 30

An AB technician must understand animal anatomy to ensure correct placement of semen in the cow’s reproductive tract. Dirk inseminating a herd on his Southland run.

See It. Believe It.

The CowManager RoadShow has been developed to provide dairy farmers, bank managers, vets and all industry related parties interested in the technology with an opportunity to speak with farmers using the CowManager monitoring system.

When: 4th March - 31st March

Where:

Starting in Northland & finishing in Southland

Register For Your Local On Farm Visit:

senztag.co.nz/cowmanager/roadshow or contact your local Senztag sales rep.

Field Event

Farm Visit Scan here for more information and/or to register for an on farm visit nearest to you.

Wife Mieke was a nurse in Holland, but now helps her husband on his AB run in Southland.

In 2020 Dirk van de Ven had his busiest AB season inseminating 11,000 cows. until Christmas, and even three weeks after,” he says.

However, he says the seasons are getting longer lasting 9-12 weeks as fewer farmers use bulls in the paddock over their herds.

“Over the last year we’ve been so busy, because the overseas AB technicians who may have flown into NZ to work during the season cannot travel because of border restrictions linked to covid-19,” he says.

Comparing the NZ system to the Dutch one, he says in Holland technicians have more opportunity to gain thorough knowledge and skill at the job because they do it day in and day out. That way they do not have a flood of animals to work with and the smaller daily number allows beginners to become experienced.

“In NZ you’re very busy for a few months, and it’s hard work for someone who lacks experience, so that’s one of the reasons why it’s hard to find good technicians,” he says.

“Still, there are good technicians in NZ but there’s more to the job than just the money – you need a connection with the animals and the land.”

He says the job requires patience, a sense of humour and most importantly, an interest in farming and an interest in caring for animals.

Dirk van de Ven runs a small hoof trimming business in the off-season from the couple’s base in Winton.

Now that he is growing older, he would like to take on an apprentice but there is an understandable reluctance from the younger generation to take up the career. If they live elsewhere and have a mortgage, they are rightly hesitant to up sticks and move to somewhere for two or three months. And if they have a partner it can be difficult for them to find a job for the rest of the year.

The size of NZ herds is a challenge for the dairy industry and the reason why the season is longer each year, with some herds in Southland having up to 1500 cows.

“So it is impossible to get them all in calf in time with natural breeding, you need AI technicians, so there is a future in the career,” he says.

“One of the answers could be more year-round calving but farmers here struggle to get good, reliable people to work 28 days a month, leaving their bed at 3.30 in the morning. How will farmers find these people when they go for yearround milking?

“Also, if you keep milking cows during winter you need to spend a lot of money on wintering barns, winter feed, machines, more cleaning and more lameness. I don’t know how you would do it in the European way.

“A farmer in Holland has about 100 dairy cows, which make him and his wife a pretty good living; they do all the work themselves from the time they’re 20 until they retire at 66. New Zealand doesn’t have the same system.”

He says he has been approached by other companies to work for them, but he prefers to stay with CRV, which he says has been a great company to work for.

“When I started 40 years ago there were a lot of small companies, now there is one large one – CRV, which came into existence in 1989. Why CRV? The people who work there work hard and like to do their job in a way that they can be proud of the company,” he says.

Dirk says he is unsure about the benefits of competition among AB companies. In Holland the job used to be much simpler when he had a limited distance to drive to local farms during a day, but today he might fill all his day with driving to farms further afield. There are now fewer farmers but several AB companies.

“Competition is also a big problem when it comes to diversity. Every company wants the best cows, best bulls and best production, and to get that done they follow the same bloodlines, which is very dangerous. You need crossbreeding because otherwise you’ll get inbreeding. There should be a law that every sire has 30 bloodlines.”

In the off-season Dirk also runs a small hoof trimming business from the couple’s base in Winton. He describes it as an uncommon practice in New Zealand, although he believes it should be carried out more often.

In fact when he applied to immigrate, he had to explain to immigration officials what the job entailed because they had never heard of it.

“They were in the North Island and called around to farmers to ask them what it meant. But in the north and in dry districts they don’t need to perform hoof trimming. However here in Southland, we have more rain.

“In Southland there are heaps of lame cows, it’s unbelievable. It’s hard to say what percentage because it differs month to month, but at an estimate about a fifth on an 800-cow farm became lame,” he says.

“Most of them you can help, but if you do nothing then the problem is solved also because a lot of the cows go to the works and that’s the end of the problem. It’s a very easy but very expensive solution – and produces poor cows.”

He says he does not carry out as much hoof trimming as he used to, partially because it is hard work, “and I’m not 25 anymore.” A Dutch trimmer has since taken over the job he used to do, although he continues to do some work. It is another job that he and Mieke are able to do together.

Does he think he might settle permanently in Holland or NZ? At the moment it looks like the latter. About 10 years ago the couple bought an inexpensive property on the outskirts of Winton and renovated it with double glazing and other improvements. It was very cheap compared to Holland – or Wellington and Auckland.

And once they can travel again, they will be able to enjoy two summers a year by dividing their time between NZ and Holland. n

Awards season frenzy

By Gerald Piddock

The New Zealand Dairy Industry Awards (NZDIA) has been swamped with entries for this year’s competition, with 366 entries received across the three award categories.

NZDIA general manager Robin Congdon says the entry numbers were more than last year and there were notably more share farmer entry numbers, which are traditionally harder to come by.

“Waikato came out on top with 66 entries across all three categories, then Canterbury/North Otago with 54 entries, followed by Southland/Otago achieving 39 entries,” Congdon says.

Awards spokesperson Anne-Marie Case-Miller says there was no single reason why entry levels had jumped this year.

Numbers tended to vary from year-toyear, with factors such as payout, weather and farm conditions playing a part.

“I do know that farmers recognise the integrity of the awards and we have got some fantastic people on the ground,” Case-Miller says.

“Our volunteers are all former entrants and winners and they’re able to say to entrants, ‘this is what entering the awards has done for us’.” Hawke’s Bay/ Wairarapa farmers Nick and Nicky Dawson won the 2020 Fonterra Responsible Dairying Award for their environmental work.

Nominations are also open for the Fonterra Responsible Dairying Award, recognising dairy farmers who demonstrate innovation and passion in their approach to sustainable dairying.

Congdon says it is important to showcase the good work farmers are doing within the industry as it does not always get the exposure it deserves.

“We have excellent, experienced dairy farmers creating and working on wonderful projects that have a positive effect on the environment,” she says.

“We want to hear about the people who are farming responsibly, both environmentally and socially, and showcasing excellence on a daily basis.

“This is a chance for people to nominate their neighbour, their employer or someone in their community.

“This award gives us the opportunity to recognise farmers that have progressed to ownership, demonstrate leadership in their farming practices and are a role model for our younger farmers coming through.” Hawke’s Bay/Wairarapa farmers Nick and Nicky Dawson won the 2020 Fonterra Responsible Dairying Award and received the John Wilson Memorial Trophy.

The Dawsons impressed the panel of judges with their genuine commitment and passion.

“We hear about succession being about family, however Nick and Nicky spoke about succession for the whole industry and dairy farming in NZ,” she said.

Nomination forms are available at dairyindustryawards.co.nz, with entries closing on March 20.

From those nominations, three finalists will be selected and interviewed by a panel of judges at the national final to be held in Hamilton next year with the winner announced at the Awards dinner

on May 15. n