4 minute read

Farmers Mutual Insurance Association

Because anti-black racism was not an adequate motivator in the northern U.S., the Klan of the 1920s targeted Catholics and Jews; and in the western part of the country, Japanese and Mexicans. The Klan said “Our Anglo-Saxon Protestant Christian civilization must be preserved.” The group contended America had been stolen from its rightful citizens, alleging that Catholics and Jews were conspiring to subvert American values, notably through immigration (which was from heavily Catholic nations in eastern and southern Europe at the time). Just as it did in other parts of the U.S., the KKK rose steadily in Iowa in the early 1920s and accelerated into a major movement in 1924. In some areas, the Klan succeeded at influencing local and state elections, including the U.S. Senate race in Iowa. Klan activities were reported heavily by local newspapers in 1924. Cross burnings were reported at Struble, Hawarden, Sheldon, Hull, Boyden and Rock Valley. The Ireton Ledger implied local support for the Klan in its report about a meeting there in May 1924: “Everyone present seemed well pleased and expressed hearty approval of the big plan adopted in the movement of Americanizing America.” The Ledger went on to publish the full “Klansman’s Creed.” While the creed was steeped in powerful language supporting American values, the Maurice Times was having none of it. The following week, the Maurice editor castigated the Ireton newspaper for publishing the creed and attacked the Klan for its opposition to particular nationalities and religions, noting that “Catholic boys, and Jews and negroes willingly gave their services and lives when America called for them to fight in the great world war. The Klan wishes to Americanize America, but the spirit of America should not be a spirit of class hatred but rather of brotherly love and mutual helpfulness between all races and creeds.” LOCAL | RELIABLE | SERVICE

This KKK uniform displayed at the Sheldon Prairie Museum belonged to an elementary school teacher who lived in Sheldon. Her father was the imperial wizard, according to museum director Millie Vos.

Advertisement

Other editors offered rebukes of the KKK and one civic organization made its opinion clear: The Kiwanis Club of Rock Rapids have openly declared that they are opposed to the organization of Ku Klux Klan in their town and at one of the their meetings recently they took a vote which was 46 to 1 against the Klan. The membership of the Kiwanis Club is made up of representatives of all churches, political parties, fraternal organizations and civic and social clubs. It was reported to the club that a Klan organizer was attempting to establish a Klan at Rock Rapids.” fmiahull.com | 712.439.1722

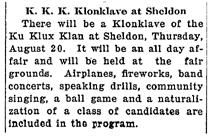

Several news reports noted Klan recruiters in the region were from Sheldon. And, in fact, Sheldon hosted the first state meeting of the Ku Klux Klan on June 21, 1924. Millie Vos, director of the Sheldon Prairie Museum, said there were 25,000 people were in attendance at the 1924 Klan gathering. A news clipping from the August 12, 1925, edition Another “Klonklave” of the Sanborn Pioneer. was hosted at Sheldon in August 1925 with attendees from northwest Iowa, Minnesota and South Dakota. Vos said a minister at First Reformed Church in Sheldon denounced the activities and behavior of the KKK. As a result, a number of people left the church and the most memorable confrontation was the burning of a cross on the church lawn. News reports about the KKK dropped dramatically in 1925 and virtually evaporated in the following years – paralleling the rapid decline of the Klan across the United States in the late 1920s. Membership was estimated to be 4-6 million in the mid-1920s, but had dropped to less than 100,000 by 1930. Some of the most hard-core believers joined pro-Nazi groups. The tide turned against the Ku Klux Klan as it was denounced by newspaper editors and opposed by groups such as the American Legion, Masons, Farm Bureau and NAACP. When the Great Depression hit, people made the decision not to spend their scarce dollars on membership in the Klan. In an exhibit at the Sheldon Prairie Museum, a former Klan member is quoted: “We met in open fields at night, tripping over our robes, sometimes shivering in the cold or rain. It was just a racket, absolutely crooked, that’s all it was. The dues were $24, which included our robe and hood. The whole thing blew up after about a year when the promoter, a tough-looking guy, disappeared with all the money, about $15,000. Everybody felt sheepish. That was the end of it.” The editor of the Sioux Center News bid good riddance to the Klan: What has time done to the Ku Klux Klan? It is a long time since I heard the subject discussed. Every man I remember as connected with that hangover of hate is very shy on the subject. Their memories will treat them with mercy and it won’t be long before time has erased it clean out of their minds … Can you imagine an old man saying to his grandchild, “Come to Grandpa. I will tell you about the time I wore a sheet over my head and went with my Klan to burn a cross at the Catholic Church corner. And that other time we whipped a big nigger.” Such bits do not pass into family lore.