13 minute read

Bold dreams built on past

| Brenda Tahi, chief executive of Manawa Honey, with her mokopuna outside the Manawa office in Ruatāhuna. Photo: Scott Sinton

Two Farmlands shareholders are part of a growing group of Māori-led businesses making their mark in agriculture. Both place tradition and values at their heart, even as they look to the future and beyond Aotearoa for growth.

People were dubious a decade ago when Tūhoe beekeepers refused to accept low honey prices and resolved to strike out on their own. Despite the eye-rolling from exporters and fellow beekeepers, the landowners established Manawa Honey to market the sweet substance that is harvested from 9,000 hectares of whenua at the heart of Te Urewera.

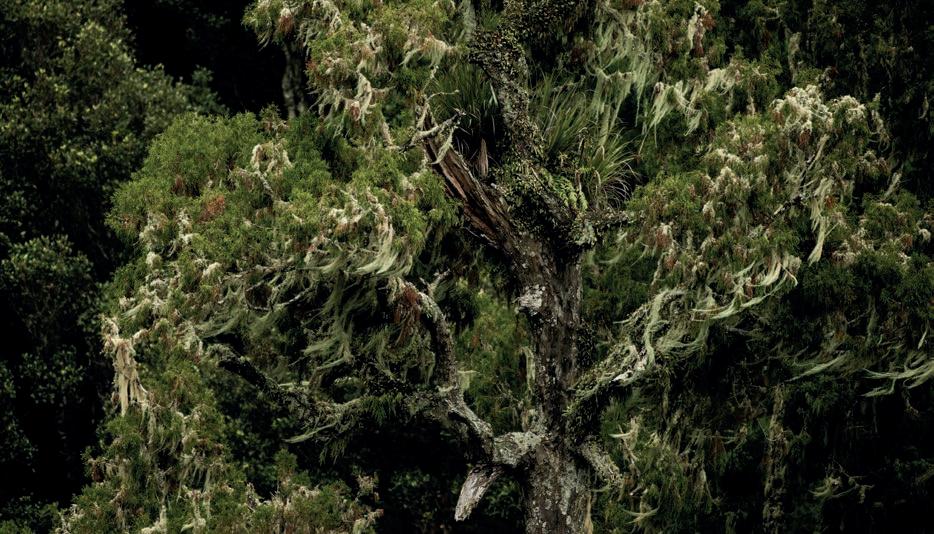

| Photos: Strike Photography; Scott Sinton

The punt paid off publicly last year when the honey company won a prestigious international competition and scooped a ‘world’s best-tasting honey’ title. Likewise, the owners of Miraka’s geothermally powered dairy factory were labelled crazy when they conjured an audacious plan to build the plant on Māori-owned land and ship their products around the globe. The factory in the tiny settlement of Mokai, near Taupō, turned a profit within 12 months. The two businesses, both Farmlands shareholders, operate on vastly differing scales. Manawa Honey will process 30 tonnes of honey this year and currently operates from a humble converted house in the village of Ruatāhuna. Miraka, meanwhile, collects 300 million litres of milk a year from almost 100 farmers and the high-tech factory employs 140 people to create goods that are exported to 14 countries. The entities have much in common, though. Both aim to help their people prosper while prioritising kaitiakitanga (guardianship and care) of their landholdings. And both place tikanga – Māori traditions and values – firmly at the heart of their business, even as they look to the future and beyond Aotearoa for better ideas or technology or new markets. They are also part of a rapidly ascending class of Māori landowner with bold, far-sighted dreams. “I don’t think many people comprehend the magnitude of Māori balance sheets,” Miraka chief executive Karl Gradon says. “Or the number employed by the Māori economy and their growth aspirations. These are big businesses, run exceptionally well and they are growing faster than most traditional business models in New Zealand.” Manawa Honey chief executive Brenda Tahi says the international honey award was a thrilling, gratifying, unexpected win and one that has opened up new sales opportunities. However, she expects the company she heads to be judged on other criteria. Entering the American honey contest was a strategic marketing decision, part of a plan to cleverly, sustainably use land held by Tūhoe Tuawhenua Trust. The trust is clear about its goal to create opportunities for whānau and hapū while protecting and enriching the surrounding forest. So the honey company is designed to create better jobs and more of them, to fund better housing and education for Ruatāhuna’s 350 or so residents. “A lot of what we do is crafted to help the development of our people,” Brenda says. “We don’t exist for the honey business. It exists for the people and the land, it’s a means to an end. Though we do love honey.” Manawa Honey has seven employees and imminent expansion plans that will bring at least another 10 jobs to the village. One

Brenda Tahi, Manawa Honey

local has learned to extract honey and a young woman has stepped into a digital marketing job straight from school. A locally born academic conducts research for the company and prospective beekeepers are shoulder-tapped to learn the ropes. “It would be easier just to advertise for a beekeeper. Instead, we find people who we think have got the right attitude, then train them from scratch. “They graduate in the work they do for us and they have a career path. We’ve been looking for decades, trying to find ways to bring people home again or stop them having to go to town to survive.” Brenda, who is Ngati Porou, arrived in Ruatāhuna as a young mum before embarking on a management career in Wellington. She returned to the village to raise children and has stayed on. It was Brenda who supplied the small house that is Manawa Honey’s head office, though a new office block and honey production plant is under construction. The trust’s land ranges over rugged country that is subject to a multitude of regulations relating to soil, land and forestry protection. Feasibility studies determined it too steep for modern farming methods and concluded it would be too difficult to do anything proactive or progressive with the land. Brenda and her trust colleagues refused to believe these findings. “We don’t expect anyone else to understand. We’re mountain people and we know the old people used to live in those mountains and were productive. Not on the scale of farming in New Zealand now, where you’ve got to clear a whole lot of land, put up a lot of fences and have a lot of animals, or a monoculture. As Aotearoa prepares to celebrate its first Matariki public holiday on June 24, Manawa Honey has rebooted a traditional trading practice. It has also added a contemporary fundraising twist to the celebratory event that honours ancestors and signals future plans. This year, the company will trade its honey for goods grown and gathered by neighbouring iwi, coastal tribes and whānau from outside the district. “Part of the ritual and celebration is to have a feast and it should have food from under the ground, in the sea, the rivers and what grows above ground in gardens, on fruit trees or in the forest. But our climate is too cold to grow kumara and we have no sea here. “As the old people traded their surplus preserved kereru and kākā – all delicacies in those days and lots in Ruatāhuna – we are trading our special food for the things we need for Matariki feast hampers.” Proceeds from the hampers will help establish a fund for the restoration and enrichment of Tuawhenua Forest. “So those who want to be part of this will be part of a network we are creating for celebrating Matariki now and into the future that connects to our land, our forests, the sea, our rivers, sustenance, fertility – actually life itself.” Further west, Miraka’s leadership team will prepare a hangi to share a meal with staff and their families to celebrate the mid-winter event. They will hold waiata and haka practices, embark on community tree-planting days and host discussions about Matariki. And in Wellington, when dignitaries gather for this year’s Tohunga Tūmau Puanga Matariki dinner, they will tuck into dishes that use Manawa honey and Miraka dairy products.

MARKING MATARIKI

“We just got named the best-tasting honey in the world. This is what this forest can produce, that taste. The complexity of the ecosystems, the mauri – life force – some of these things come through as taste. You can’t produce that if you do monocultural stuff.” In earlier centuries, Tūhoe people did not grow large-scale crops in the way of neighbouring iwi. “But they still did cultivate and produce and they were integrated into their forest.” Wild honey gathering – te nanao mīere – was incorporated into this tradition following the introduction of honey bees into New Zealand in the 1830s. The honey was considered a taonga (treasure) until varroa mite exterminated the bee population in 2000. It made sense to bring bees back to Te Urewera, Brenda says. Within 10 years of the winged insects’ departure, clover crops were starting to disappear from farmland and residents noticed their heritage home orchards were no longer fruiting. “The forest has been supported by wild honey bees for nearly 200 years and all of a sudden they were gone out of the ecosystem.” Tūhoe Tuawhenua Trust decided to take up beekeeping, reasoning it would restore this imbalance, provide employment and encourage increasingly urbanised residents to venture back into the bush. Brenda pinpoints the genesis of Manawa Honey to the day Ruatāhuna beekeepers were offered a shockingly low price for their honey, all of it harvested from Urewera bush and imbued with the distinctive flavour of māhoe tree nectar. Yet payment terms were worse than those for common clover honey. “[Aside from manuka] the industry had no way of valuing honey with provenance, no attachment of value for its taste. I just couldn’t sell for that price. “So we decided to go straight to marketing. Other exporters and brand owners laughed at us because we were so small. Most people have 50 tonne before they establish a brand but strategically, that was the thing to do.” The trust is continually seeking diversification options for its whenua and is unafraid to look outside the square and overseas. Trust representatives have visited mountain villages in northern Thailand and southern China to find out how other mountain-dwelling people use their land. They saw tea and coffee, rice, herbs, peppers and much more grown in forests. Brenda says while the crop specifics may differ, the farming concepts and methods are potentially relevant to Tūhoe people. She describes indigenous tribes using cyclical crop rotation and permaculture-style planting, with small areas of forest burned off to create regeneration over decades. The trust is also looking for answers closer to home, drawing on Western science as well as traditional Māori practices. During COVID-19 lockdown, Manawa Honey delivered koha – a gift of honey – to every Ruatāhuna home. Each local marae receives a bucket of honey annually. Karakia are uttered before each meeting and each time their beekeepers travel out of the district to check hives. Work is under way to align other practices such as honey harvesting or planning meetings with the maramataka (Māori lunar calendar), to maximise chances of success. A series of Landcare Research studies, spanning almost 20 years, have examined everything from traditional mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) through to environmental DNA analysis and carbon dating on their land. “We’ve got an eye to the past but we’re in the present. And we’re embracing new technologies to take us into the future. We don’t have all the answers but our old people didn’t just stay with old knowledge, they embraced new things. “We know our forest has been modified by moa, fire, lightning, our people. So it’s not just about preserving forests, you’re working with a complex ecosystem. And our responsibility is not just for the land, it’s for the people. We’ll consider everything available to help us understand.” On Karl Gradon’s first day in the top job at Miraka, he was welcomed with a goosebump-inducing haka performed by every factory worker and manager. During the performance, a tall Korean stood shoulder to shoulder with the Māori haka leader, surrounded by 18 other nationalities. A guitar lives in the operations room of the multimillion-dollar company for just this kind of occasion and morning toolbox meetings begin with a karakia and usually incorporate some te reo practice. When one farm is nominated to receive help with its riparian planting programme later this year, Karl will don his Red Bands to plant trees alongside everyone else. A month into his new role, the Pakeha chief executive is still a little incredulous at the practical, daily demonstrations of what the company calls Te Ara Miraka – the Miraka way. “It is exceptionally different,” he says, comparing the company culture with that of his previous dairy industry workplaces in Aotearoa and Ireland. “And it is only for the better.

| Miraka's business plan stretches forward a century.

| Miraka’s geothermally powered dairy factory at Mokai.

Karl Gradon, Miraka

“Tikanga is not something that’s easy to define but the Miraka way embeds it to the nth degree. We are uniquely and proudly Māori. It instils a lot of pride in the reo, the culture and the way we operate in our community. The tikanga principles are what bind us together.” Whereas most organisations he has worked for operate a 5-year business plan, Miraka’s stretches forward an entire century. “It’s interesting. At Miraka, you can have a couple of speed bumps today but that won’t alter the course. You can take a longterm perspective of where we’re heading. And all the profits end up back in our community, which is not something you can say for multinationals or private family dairy companies.” What’s more, the dairy processor boasts a carbon footprint that is 94 per cent lower than its global competitors thanks to the company’s reliance on renewable geothermal power rather than coal. The entity was formed in 2010 when several Māori trusts joined to build an environmentally and economically sustainable dairy factory. Karl shakes his head at the visionary audacity of those early proponents of the concept. “They had this great vision that you could sustainably farm dairy and produce a product for the global market with kaitiakitanga at its absolute heart. “Some thought they were crazy. If you look back 15 years, when the idea really began, there were more climate change deniers, in some of our markets, than believers. Since then, you could say the global consumer has caught up.” He says overseas buyers are seeking out sustainably grown and produced food with a known provenance. They are demanding carbon neutrality and paying a premium for it. About 30 per cent of the farms that supply milk to Miraka have Māori owners. The rest willingly sign up to the same lofty standards in animal welfare, sustainable land management, people management, milk quality and well-being. All suppliers receive a financial incentive on top of the milk price, for meeting these standards. Karl says the company attracts suppliers with similar values, including adaptability and forward-thinking. He says this is particularly noticeable in the face of increasingly stringent environmental or animal welfare regulations. “So instead of reacting to legislative changes – and legislation is always improving and tightening, as it should – they’re adapting well beforehand. They’re already 4 or 5 years ahead in their thinking.”