Spring 2023

Section Editor

Trisha Khattar

Content & Copy Editors

Amariyah Lane-Volz

Gigi Clark

Purva Joshi

Kayleigh Morrissey

Staff Writers

Mariah Hernandez

Christine Barnfield

Amanda Mak

Selena Perez

Kate Barrios

Kaycee Stiemke

Section Editor

Kimia Faroughi

Content & Copy Editors

Shreya Kollipara

Isabela Murray

Aleea Evangelista

Valia Chin Staff Writers

Vanessa Diep

Anisha Girotra

Noor Hasan

Valeria Chavez Nunez

Tongtong Zhang

Sharanya Choudhury

Minnie Seo

Reya Hadaya

Daniela Lopez

Sophia Obregon

Section Editor

Kelsey Chan

Content & Copy Editors

Julianne Estur

Amanda La

Dev Dharani

Talia Way-Marcant

Bianca Badajos

Marie Olmedo

Lindsay Land

Staff Writers

Jamila Cummings

Amber Phung

Trisha Badjatia

Bella Garcia

Madeline Juarez

Gemma Greene

Lilah Eden Peck

Jessica Renee Thomas

Section Editor

Tessa Fier

Content & Copy Editors

Sarah Huang

Lauren Vuong

Maggie Christine Vorlop

Staff Writers

Camille Neira

Sristi Palimar

Siya Sharma

Maria Cecillia Smurr-Ferrer

Section Editor

Angela Patel

Content & Copy Editors

Eva Speiser

Sabrina Ellis

Jalyn Wu

Anouska Saraf

Najda Hadi-St John

Gwendolyn Hill

Staff Writers

Alexus Torres

Geneva Flores

Mira Getrost

Malvika Iyer

Finance Co-Heads

Abby Giardina

Zoë Collins

Finance Staff

Esther Cabello

Sydney Shane

Radio

Radio Head

Kelsey Ngante

Radio Producers

Amber Stevens

Marie Olmedo

Tiffany Peverilla

Muryam Hasan

Leah Hartwell

Emily Sophia Haddad

Elsa Servantez

Video Head

Cassidy Kohlenberger

Video Producers

Anna Ziser

Gia Blakey

Kailyn Barrera

Reina Cooper

Community Outreach Co-Heads

Cali Perez Chavez

Bobbie Sturge

Community Outreach Staff

Olivia Sieve

Dev Dharani

Madeleine Wang

Sarah Mousseau

Social Planning Head

Anna Mook

Social Planning Staff

Kristin Haegelin

Jessica Do

Kaylynn Pierce

Casey Rawlings

Cynthia Robles

Social Media Co-Heads

Reika Goto

Cassandra Sanchez

Social Media Staff

Mandy Tang

Alyssa Adriano

Aashna Sibal

Faith Forrest

Sanchita Pant

Design Co-Heads

Coral Utnehmer

Cassandra Sanchez

Design Staff

Katelynn Perez

Tia Barfield

Erin Choi

Katherine Mara

Eleanor Kinsella

Ashley Luong

Kate Paige Vedder

Bianca Badajos

FEM, UCLA’s feminist newsmagazine since 1973, is dedicated to the empowerment of all people, the recognition of gender diversity, the dismantling of systems of oppression, and the application of intersectional feminist ideology for the liberation of all peoples. FEM operates within an anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist, anti-racist framework. Our organization seeks to challenge oppression based on sexuality, gender, race, class, ability, religion, and other hegemonic power structures. We create a wide range of compassionate multimedia content that recenter narratives often rejected or ignored within mainstream media. Beyond journalism, FEM engages in actionable praxes by building coalitions with other campus and community members. As self-reflective feminists, we are committed to unlearning and relearning alongside our global audience as the sociopolitical landscape in which we are situated continues to transform.

FEM Newsmagazine is published and copyrighted by the ASUCLA Communications Board. All rights are reserved. Reprinting of any material in this publication without the written consent of the Communications Board is strictly prohibited. The ASUCLA Communications Board fully supports the University of California’s policy on nondiscrimination. The student media reserve the right to reject or modify advertising whose content discriminates on the basis of ancestry, color, national origin, race, religion, disability, age, sex or sexual orientation. The ASUCLA Communications Board has a media grievance procedure for resolving complaints against ant of its publications. For a copy of the complete procedure, contact the publications office at 118 Kerckhoff Hall, @ 310-825-9898

Youth encapsulates significant components of one’s life story. It is valued differently throughout space, time, culture, and environment. Childhood for me encompassed princesses, fresh fruit, monkey bars, and clashing outfit patterns. Youth holds power in its appreciation of energy and the little things.

In many cases, youth is associated with physical appearance, aesthetics, and beauty, with worries of aging instilled in us through media. From makeup and style trends to social activities, youth is valued by mainstream society and desired by many.

It’s believed that youth begins to dissolve during a coming of age in your teenage years. But some people have to grow up faster than others. With a few weeks left of my time at college, the real fears of adulting have set in and I feel as if I am losing some of my youth. However, I know that my inner child blooms within me and will guide me through this next chapter of my life.

Youth embodies so much more than just the transition between childhood and adulthood, or the shift from one version of yourself to the next. Youth represents dynamic and transformative collective power that spans generations. As the world continues to evolve, so do new alternative forms of survival, resistance, and support, to challenge the existing systems of oppression. Intersectional feminists of all ages have contributed to the lasting thread of community building and liberatory work for all marginalized peoples.

In this note, I would like to pass the title of Editor-in-Chief to Bella Garcia, who will continue to allow FEM to thrive. Bella, you will have full support from the FEM Community in leading our publication next year, and I am so excited to see FEM under your guidance from the sidelines.

Thank you to my amazing managing editor, Sophia Obregon, who has helped me make FEM’s accomplishments this year possible — we did it. Thank you to Senior Staff for your care and commitment to FEM’s mission. I am incredibly grateful to FEM staff and the FEM community for making my three years in this organization so special and a highlight of my university experience. The people in FEM have strengthened my feminist practice and provided me with immense support throughout my time as EIC, for which I am profoundly appreciative. I am truly so honored to be a part of the legacy of 50 Years of FEM Newsmagazine and am looking forward to the organization’s bright future.

I present you with our Youth Issue, proposed by FEM Member Sabrina Ellis. Our writers, designers, and creatives traverse the complexities of the youth experience, and the ways in which it informs identity, feminism, and more. Enjoy the Youth Issue!

With love, and signing off, Mar

Escusa Editor-in-Chief 2022-2023

Editor-in-Chief 2022-2023

By Jessica Renee Thomas

By Jessica Renee Thomas

As a 21-year-old junior in college, I can’t help but refl ect on my adolescence and ask myself what could have been. A lot of what has shaped my worldview is movies, and for as long as I can remember, I have been waiting for my big coming-of-age moment. A moment or period of time that would drastically alter my perspective on life and breathe renewed energy into said life. Consequently, this has led me down a road of harshly judging the stories that take precedence in female coming-of-age movies. The coming-of-age movies centered around female protagonists are often burdened with heavy realities that young girls face. It’s not uncommon to watch a coming-of-age movie with a female protagonist that deals with the topic of teen pregnancy, sexual abuse, etc. — think of movies like “Juno,” “Saved!” or even “The Virgin Suicides.” Young girls are thrust into the adult world before they can truly begin to have fun. Even when they experience the joys of being young, there’s this overwhelming burden that just one misstep will drastically alter their lives. In contrast, in male-centric coming-ofage movies like “Superbad” or “The Lost Boys,” the plots refl ect the never-ending youth men get to experience, as their issues revolve around nonconsequential sex or monsters. To put it simply, they get to have fun while girls have to reckon with the horrors of real life.

I desperately wished that more female coming-of-age movies would have the same carefree, nostalgic aura that male coming-of-age movies have. It was easy for me to write these drastic differences off as a byproduct of male Hollywood executives not being able to write stories that speak to the girlhood experience and, at the same time, provide the same type of fun present in these male-driven coming-of-age movies. And while in many cases this is very true, I now believe that these differences are much deeper, refl ecting the different realities men and women get to exist in. For girls, coming-of-age is a terrifying path towards self-discovery. Young girls don’t need to slay monsters because their monsters are all too real and pose very real threats to their lives. In reckoning with the fact that girls will never get the same coming-of-age movies as boys, I realized that it would be more worthwhile to celebrate the coming-of-age movies that are directed, written, and starring women that really speak to my own coming-of-age experience and the experiences of those closest to me. To mourn what could have been is pointless, especially when real stories that speak to the diverse experiences of girlhood are here and ready to be told.

I can’t say that my own teenage experience was burdened by the extreme societal pressures of the likes of teen pregnancy, but rather this overwhelming desire to “better” my situation. My entire life revolved around academics because I never really thought someone of my socioeconomic status could go to college, especially one like UCLA. Upon entering UCLA, I have come to realize that many of my peers do not have the same relationship with higher education as I do. When I was growing up, no one I knew in real life went to a prestigious four-year university. I didn’t even know what UCLA was until the fi fth grade when I wrote a report about FloJo, which inspired me to make attending UCLA my life’s goal. I now wonder if this one goal was really worth what I put myself through during my high school years. I was so determined to get into this prestigious school that I put myself in self-imposed isolation. I truly believe that growing up as a lower-income girl made me feel like the weight of the world was on my shoulders, as if my family’s future success and prosperity were riding on my high school academic career. Now being at UCLA for three years, I can’t help but feel disillusioned. Like I stunted my social growth and made myself incapable of being able to relate to people my own age. I have grave anxiety about the most minor things, like going out and having fun, which a young person like me should be doing. But most of all, I have this deep fear of growing up coupled with the feeling that I missed out on my key developmental years.

It wasn’t until I watched “Booksmart” that I really felt seen in the coming-of-age landscape. It was the story of two overachieving girls so caught up in their desire to attend prestigious Ivy League universities, they didn’t

realize the people that they pegged as “slackers” were moving onto the same schools as them. The only difference between them and these “slackers” was the fact that they made the most of their high school experience. This movie, while falling into the trappings of many white feminist tropes, does the greatest thing a movie about girl overachievers could possibly do — tell the audience that there’s absolutely no reward in devoting your entire life to the grind. Rather, you should actively have a life and identity outside of it.

While both of the main characters are interesting in their own right, I felt particularly drawn to the character of Molly, who used academic achievements to put herself on a pedestal above her classmates. It is apparent that scholarly achievements were really the only identity she had, so the bitter reality that everyone else was also doing well made her doubt everything she knew about herself. Realizing that her peers were able to balance an academic and personal life leads her down a road of self-discovery, as she devotes the night before graduation to going to her fi rst party and experiencing the debauchery that all her classmates got to.

The difference between Molly and me, however, is that I still feel that I never got this “coming-of-age” moment. It wasn’t until I actually got to college that I realized there was no reward in dedicating my entire life to professional pursuits. And, most of all, I wonder if it’s too late to get my moment of self-discovery. I have this overwhelming feeling that my youth — yes, at 21 years old — has passed me by and that for the rest of my life, I will have to reconcile with the fact that I grew up too prematurely.

While I heavily identify with a movie like “Booksmart,” which sees two female protagonists reckon with having an identity outside of academia, I can’t help but see my mother in a movie like “Just Another Girl on the I.R.T.” This fi lm presents an alternative perspective of coming-of-age, as it centers an ambitious, fl amboyant girl from New York who dreams about becoming a doctor despite her surroundings. Her goals and ambitions come to a halt when she becomes pregnant. No longer is she vibrant and outgoing, but instead riddled with fear over what a baby would mean for her future. This movie shows how all-encompassing a pregnancy, at any stage of life, is for a woman. A mother is made to feel that she is supposed to lose herself, as she is expected to give every bit of herself to her child. No longer can our protagonist, Chantel, dream about being a doctor, as her only future is being a mother. In a fucked up way, teen pregnancy can be thought of as zapping the youth out of the mother and transplanting it into her baby.

Selfi shly, I thought about how my mom might have had her own future mapped out in front of her prior to getting pregnant at 17 with my sister. I thought about how she might have dreamed about being a doctor or going to college. Most of all, I thought about how my siblings and I ruined her life and her chance at youth. Upon talking to my mother, however, I’m met with a completely different perspective. Before getting pregnant, my mother didn’t have a plan for herself and, by that point, had completely stopped going to school altogether. It wouldn’t be until much later in life that she had a moment of self-discovery. In her 30s, she decided to become a pharmacist technician, and in her own words, she did it purely for herself.

Similarly, Chantel, after giving birth and reckoning with the reality of being a new mother, refuses to give up on her goal of being a doctor and ultimately still pursues her education — a goal that is strictly for herself. While the world might want mothers to metaphorically give their youth to their children, women like Chantel and my mother prove to the world that motherhood isn’t the severing of youth. Rather, it is just another new chapter in their book. In this way, they both rewrite not only what motherhood looks like but also what youth looks like.

This brings me back to my fear of growing up and losing touch with my youth. This burden of feeling like my life is running away from me no longer feels as heavy as it once did. Refl ecting on my mother’s youth and refl ecting on the person she is today, in her early 40s, makes me feel like I can still catch up to mine. It even makes me wonder whether coming-of-age and being young are as interwoven as I once thought. Last August, my family and I went to Disneyland for the fi rst time, and I can’t get my mother’s huge bright smile out of my mind. It makes me less obsessed with waiting for my moment of self-discovery to happen because my mother proves that coming-of-age is a forever process and the metaphysical concept of “youth” never truly dies. When I’m with her, her silly jokes and childish demeanor make me feel 10 years old again and like the world is still at my fi ngertips.

Design by Tia Barfield

Design by Tia Barfield

In the couple of months following my fi rst tattoo (or rather, my fi rst tattoo that is publicly visible)

I saw myself as a changed woman — as corny as that is to admit. I had made a decisive change to my outward expression, to the way that people perceived and understood me. Whatever my personal identity may be, however I work my tattoo into that, it was from that point on literally inextricable from myself. Idle, contemplative moments were spent peering down at the little man on my arm. Brandishing his scythe proudly above his head, my red-cheeked gardener surrounded himself on all sides by fl owers — the fruits of his labor, I imagined. He, with the placid and contented smile on the puny, tic-tac sized face that rests in the soft fl esh of my left bicep, is a wel-

come companion. My f(arm) er is colorful and cute, storybook-like, even. I put him there, quite honestly, for no reason in particular. I knew I had no reason to welcome him onto my skin, or at least none in the vein that people are looking for when they ask, “so, what do your tattoos mean?” Frankly, I have no aspirations of fl ower-farming or scythe-wielding, nor does anyone else I know. That wasn’t what it was about, for me.

My impulse to get tattooed came from a place of playful joy: to happily romp and muck around in the unruliness of my fl eshy form. I have never been someone to keep my sneakers clean and crease-free, or have a phone too long before cracking it. I just can’t be bothered. I think of the little man on my arm in a similar way. You only get one go.

Still, I anticipated with angst and embarrassment the conversations that would surely come when tasked with communicating my lackadaisical connection to the blankness of my skin to friends, family, or passersby. I expected amusement and a fair share of appreciation, as well as veiled criticisms, and have received exactly that.

What shocks me, though, is what people say when I turn the question around on them, sloughing the spotlight away from my farmer, letting him fall back into place against my ribcage. “What about you?” I ask. “Would you ever get a tattoo?”

Practically without fail, the tattoo-averse justify their decision to remain un-inked with an unease and anxiety over the idea of growing old with a tattoo. “How will it look when I’m older?” they wonder, grimacing at the idea of a skin-bound fl ower whose petals are faded, wilted, wrinkled and sagging. “What if I regret it?” they contemplate, imagining being marked with lyrics to a song whose melody became rote and tired years ago.

How silly, I thought, to imagine yourself old and worn, inhabiting a body and a life that is so unlike the one you have now, in form and function, and cast judgment. How silly, I thought, to assume that 20 years from now, what will preoccupy your mind will be how the tattoo you got decades ago no longer looks the way it used to. In reality, aging entails experiencing changes and degradations to your body that will, in all likelihood, be painful and have pervasive and life-altering impacts. To be wrought in self-imposed shame over a tattoo, to add to the pain of going old in this completely unnecessary way, just seems cruel. When their worst fears come true and their tattoo from decades ago has morphed into a saggy, faded, blurry beautiful mess so too will another, bare arm be just as wrinkled, just as marred with the same signs of a life lived.

I don’t mean to proselytize the non-tattooed. I’m not here to convince anyone that to be tattooed is somehow right, more courageous, more feminist. The judgment that I felt towards the reservations these women voiced to me are callous and blind to the realities of the pressures of femininity. There is a genuine anxiety that underlies these doubts about tattooing, and the more I heard it voiced by these women in their decisions to adorn their bodies (or not), the more the root of this fear became apparent. The ideal form of femininity, societally prescribed and enforced, is clear and pervasive. Young women are called to understand and defi ne themselves in the context of their appearance, youth and purity. There is a feminine ideal — the force, pull and judgment of which we all feel — that is pure, beautiful, subservi-

ent, and constantly projected upon. To be a woman or femme, in the social world at large, is to an extent to be understood as an object of an external other’s gaze. Of course, this gaze is one that excludes both tattooed and aged skin from its feminine ideal. Tattooing is, by necessity, a highly personal practice. They are paradoxically external, consumed by all onlookers, yet private, entrenched in personal meaning and signifi cance. Others are invited to see a tattooed body and infer meaning from marks they know little about. Regardless of whether your tattoos bear a deep, personal symbolism, it is a vulnerable expression to wear so visibly and externally a self-defi ned beauty standard. Tattoos can be an externalized statement of identity and individuality. Women and femmes are acutely aware of the ways in which our bodies are read, consumed and gazed upon by others. Making this kind of a bodily statement, to offer up another part of oneself to be misunderstood, judged and misread, understandably carries weight. What this anxiety belies is an unfortunate discomfort with the reality of the degradation of our bodies as something we can enjoy. I don’t mean to make out the person who fears death and old age to be a fool. I don’t even think that is necessarily the type of fear that is at play in a young woman’s unease to bear on her skin an old, blown-out tattoo on her skin. The fear lies, I think, in the prospect of existing in a body that deviates from the standard of femininity in more ways than one.

There is a tension here, both a seizing and a forfeit of control. Tattoos are forms of art that are one with us as natural beings; they are, just as we are, in constant motion and fl ux. To get tattooed is an embodiment of the desire to shape and morph the body you inhabit, to create a beautiful and unique form of self through this bodily expression. There is an unmentioned understanding that while this change is permanent, it is only as permanent as we are. We offer our self expression up to the gaze of others and the degradative powers of time. No matter how blown out, how faded and warped a tattoo can become, there is always beauty in that motion.

One’s coming of age is marked by both big and small revelations. At ten, this was my big small revelation: I could wish to see two fi ctional characters kiss.

This was the year I was homeschooled. This was the year of pining for 1) friends and 2) for my bright pink bedroom to not be bright pink anymore.

The internet became my best friend, allowing me to discover anime music videos (AMVs) on YouTube. I was obsessed with “Pokemon: Diamond and Pearl” at the time, and was hungry for content outside of the show.

Then: the Revelation.

I stumbled across AMVs of Ash Ketchum and his female companion for that particular series, Dawn, who was my favorite character back then. There was one to “Kissin’ U” by Miranda Cosgrove, another one to “Good Time” by Owl City featuring Carly Rae Jepsen. And of course: “Everytime We Touch” by Cascada.

This was a fi eld day for the year I didn’t have a fi eld day.

I’d always thought they could be cute. Their signature thing in the show was a high-fi ve. So theoretically there were many times they could’ve been holding hands if one of them just made a move. Except “Pokemon” wasn’t focused on romance at all, so nothing happened. I fi gured there was no point in entertaining such a silly fantasy. I was shocked that this was a Thing, and that this Thing had a name, and that it involved content. Edits. Art. Fanfiction (!!).

What compelled me most was the act of shipping in itself, how it was pining for romantic possibility. I learned quickly that some ships had no chance of becoming canon. And yet, isn’t everything so much lovelier when you can fi nd love everywhere?

It’ll never happen, I read detractors on forum sites say.

Years later I would see this pessimism refl ected in the modern state of dating. I would have many conversations about how dating apps feel dystopian and how it makes me feel like everyone, including me, is a commodity on a shelf. I would see many comments mocking heartbroken people and scoffi ng at their vulnerability. I would cry many times because I just want to be cared for by someone else, and then cry even more (angrily) because I am supposed to be a Strong Independent Woman who doesn’t need anyone.

Eventually, a decade later, I will be able to admit it, if only to myself. It’ll never happen, the voice in my head says. But isn’t there something so pure about wanting, full stop? ten-year-old me says.

ash and dawn, since 2010 i have moved states. i’ve lost all my baby teeth and outgrown the clothes i wore when i was watching you. all of my stuffed animals are gone. sometimes i miss them. but you’ve never left me. when i got my heart broken, i came back to you. i cried in your lap while you stroked my hair and said it was going to be okay. it feels good to love you. even better to know that it’ll never change. how many things in life can we say will never change? we’ve got something special.

The fact that Blue and Green from the manga “Pokemon Adventures” interacted maybe three times didn’t stop my 15-year-old self. Half a decade into this shipping journey, I caught onto the fact that what was actually there didn’t matter as much as what could be there. Stoic and broody boy and fl irtatious and irritatingly clever girl? Sign me up.

It was more fun that there wasn’t much material to work with. Nothing made me happier than observing a detail in their individual backstories or reactions and thinking, “This is an area where they’d relate to each other if the author was smart enough to make them talk!”

And maybe it was a little self-indulgent because I had crushes on both of them and I liked the idea of seeing two hot people being hot together.

I had never dated anyone. No one had ever even liked me; I spent many nights with my growing pile of unrequited crushes and wondered if I was just unlovable. Some of my friends had already experienced romantic love and I was here, making up scenarios in my head about two fi ctional characters. Even as I thought about them, I still found myself sad because it was all just speculation. What was the real thing, and would I ever know it? I was grasping at straws both in real life and for this ship. But looking back, I can’t help but love the younger me for this, for magicking love out of thin air.

blue and green, nobody gets you like i do. no, really. i don’t have a lot of competition (there are only 100 fics on archiveofourown) but even if i had to fight a million people, i guarantee i would win. they say love is understanding. and i love you the most. as long as i’m alive you’ll always have someone on your side.

Akira Kurusu and Goro Akechi from the video game “Persona 5” carried me through the pandemic. I made an entire playlist of Taylor Swift songs retelling their storyline in chronological order, along with a fi ve-page document detailing why I chose each song. My private stories consisted of posts of me just rambling. This is the most unapologetic I had ever been.

I have a complicated relationship with their source material. Despite providing many female dating options for the teenage Akira, including his teacher, there are no options to date the male characters. Yet his relationship with Goro is central to the game; Goro plays the detective who is investigating The Phantom Thieves, the protagonists. Eventually, he joins. Even later, it turns out Goro is the person who has been committing murders to frame The Phantom Thieves. And to get even more nail-biting, it’s revealed that the god Yaldabaoth pit Akira and Goro against each other to see which side of humanity would win. Towards the end, Akira convinces Goro that there is a chance for redemption, and then Goro… dies. Killing him off instead of seeing his atonement through always felt like a cop-out to me.

I was hooked.

Some might think it’s depressing to love a ship that ends tragically. I disagree. To love them even knowing how it ended, and to still dream of a better ending, made me feel strong. “It’s better to have loved and lost than to not have loved at all” was a lesson everyone learned. I learned it from them.

People wrote fanfi ction where they do end up together, people wrote stories where Goro survived, healed, and became objectively a more complex and nuanced character than in the source material. Fans get disappointed because they often see the way things could be, whether that’s in terms of representation or something like a character arc. They reimagine the worlds of these pieces of media,

and through things like fanfi ction, they make it happen.

People tend to denigrate fanfi ction, and fandoms as a whole — these spaces are often queer and female-dominated.

“Fangirl” has always meant someone who was too obsessive, too loud, too annoying.

But me? I’m in awe. I want to be that full of hope. I want to never lose sight of the way things could be.

goro and akira, please stop breaking my heart. but there is no one else i’d rather have break my heart than you. something no one ever told me is that the only thing more devastating than a doomed romance is a romance that works out. i get weak in the knees thinking about it. i’ve always wanted you to be okay, and then more than okay. i swear i will love you into a happy ending. you can trust me. promise.

I was nineteen when my fi rst love and I broke up after 3.5 years. All the self-help websites talked about healing your inner child.

So I got back into “My Hero Academia.”

I was obsessed with the series from 2017-2019. Certain events in the manga I heard about on Twitter brought me back out of curiosity.

And well.

Hard launch: I am presently eight months deep into what is most defi nitely the most intense media obsession of my lifetime.

My love for “My Hero Academia” was deeply intertwined with my affection for the ship of Izuku Midoriya/Shouto Todoroki. They still feel like home to me. It’s strange — though they were the show’s most popular ship back then, the consensus nowadays is that they’re too “boring.” It’s a friends-tolovers ship, and to put it simply, there’s no drama. Nothing like the juicy and cosmically devastating angst my last ship obsession provided.

I should think they’re boring too. My breakup made me skeptical of the rose-colored idealism of fi rst loves, high school relationships, and so on. It felt too easy.

I’d describe their love as easy.

And yet this is the most I’ve ever been active in fandom. I’ve bonded with so many strangers on the internet by crying over them. There’s nothing else I’ve talked about more this year, probably. Like when you have a crush and all you wanna do is talk about it.

Nowadays when I feel like I’m losing faith I reread chapter 249 of the series.

“You’re an incredibly kind person,” is all Izuku says to him. But Shouto just looks at him like oh Oh, I think, softening, unfurling.

(Deep down, I want things to be easy.)

izuku and shouto, this year marks seven years since the first time we met. my friend makes fun of me for calling you izuku and shouto. “you’re on a first-name basis with them,” she said. but the funny thing is that she’s started calling you that too. she says i’m infectious. i just wanted to tell you that lately i’ve been walking with a bounce in my step. every song’s about you. i would like to write you a bad poem. when i look at you i feel tender in the heart. i like you more than i like anyone else. i do. i really really do.

The thing about love is that I don’t think anyone can put it into words. Not really. I could write a neat little thesis statement about how shipping is an inherently hopeful endeavor that has taught me to stay optimistic in all things, in the face of a world that gives us so many reasons to harden our hearts. I could tie it all up by saying that shipping has healed me in so many ways by allowing me to stop being “strong” for once so I can just yearn so hard for tenderness that I feel it in my chest. But I don’t think anything I can write would do it justice.

After all, how can you defi ne forever? The love I have for my favorite ships has been the most enduring and steadfast love in my life. People come and go. That’s life. People may hurt me. That’s life too. But I’ll always have this love, and what I fi nd so powerful about it is that no one can take it away from me because it comes from me. If shipping is an act of hope, then I have so much hope in me that I think I might be blissfully crushed by it.

I still have trouble being honest about the “wanting love” thing. Even as I write this I wonder if this is lame or corny.

So I’m not there yet. But I have hope that one day, I will.

I have an overly active imagination, so I can picture it now. I hope it’s the combined euphoria of myself, at every stage of life, witnessing every single one of my favorite ships’ moments. I hope it’s even better.

I think it will be.

to whoever comes next, we haven’t met yet. but i’ve loved you all my life.

Design by Katherine Mara

Onone quiet morning, in a political science class just barely fi lling two complete rows, I sat alongside a burnt-out group studying a dense workload when suddenly the entire class jolted, and our typically agile professor dropped his pen.

A loud and sharp bang came from the outside of the hallway and we froze. A few seconds passed, and the professor and I nervously held eye contact after a quarter of only polite small talk and friendly exchanges. He resumed the lesson. Until, again. Another loud slamming noise escaped the halls and seeped into the cracks of our classroom door. We all sat quiet, still, the professor visibly in distress, the students not so much as blinking.

The banging noise came from the doors outside the class shutting, doors made with aluminum closers intended to soften their slam. On that particular quiet morning, they had failed to do their softening job, and at that moment, we were not thinking about aluminum closers. Our worst imaginations ran free. In reality, there was no gunman skulking down the hall and there was no need for a desperate internal prayer monologue (God if you’re there I promise...). We were just a classroom full of tired and scared students.

I try to understand this collective fear as being a legacy of children and adults who endured a world of “Sandy Hook,” “Uvalde,” “Parkland,” and watched absolutely no gun-control policy come of it. Surely my 11 year-old self thought after my 2012 post-Sandy Hook gun drill that the trusty members of Congress would get together and protect me. That they would protect my friends and my teachers, and never fail again in the way the government failed the children and teachers of Sandy Hook Elementary just a few days before the school’s Christmas break.

But on the issue of guns, the members of the United States Congress and government are failures. A failure today, a failure yesterday, and a failure every single day legislation falls short of protecting against

the brutality of guns.This is best attributed to the legislative powers of the fi libuster. Powers that continue to be weaponized by the Senate’s Republican leadership and powers that continue to murder children. To understand why and how the fi libuster has been such an integral roadblock to passing any substantive means of gun control, it is important to analyze its history. The fi libuster’s key purpose is to allow for unlimited debate in order to delay a bill getting voted on. To end the period of debate over a bill, which would effectively end the momentary fi libuster, the Senate must reach a cloture vote, which takes 60 Senators (a 3/5 majority). With today’s Senate split almost evenly (Democrats nowhere near 60), it is clear why any meaningful gun control bill or assault weapons ban has not been achieved. The actual House of Representatives website itself calls the fi libuster’s process of blocking a bill, “talking it to death.”

The system of the fi libuster works collectively with the countless members of the Senate (House too but the Senate is really the key player) who receive campaign funding from the National Rifl e Association (NRA) to prevent gun control. As the central force behind the gun lobby, the NRA spends millions of dollars annually to support the campaigns of Republican Senators who further the Association’s “Second Amendment” agendas. The list of Senators on the NRA’s payroll is disturbingly long. With over a million dollars towards his campaign, notorious Kentucky Senator Mitch McConnell leads the party’s efforts to uphold the violent agendas of the NRA and organizations who fund Republican campaigns.This is the same person who, in 2010, promised Wall Street he would block bills that would hold them accountable for causing the Great Recession so long as they agreed to fund Republican campaigns. The Senate leadership guides the party, and if consolidating power in Congress means clutching the fi libuster and taking NRA blood money, then they will do just that.

The leverage of this money emboldens the gun lobby to act as the puppeteer of Republican leadership,

like McConnell, and severely impede any substantial means of change in doing so. Worth noting are the exceptions to what is (largely) an issue that falls along party lines. Henry Cuellar and Ron Kind (how kind are you Ron?) are two House Democrats that voted against the June 2022 bipartisan gun control bill. Unsurprisingly, both Cuellar and Kind have received gun lobby funding. Kind was endorsed by the NRA during his run for offi ce, and Cuellar not only received NRA funding, but an “A” rating from them as well. The Democratic Party’s traditional clutch towards status-quo politics continues to be an intrinsic fault hindering their minimal gains on gun control. If Democrats continue to use gun-control for their own campaign strategies then they must consistently demand change, become irritating in doing so, and not wait to capitalize upon word of a mass shooting to keep pushing forth legislative proposals. With the unwavering stagnation across party lines and powerful gun lobby, it is no wonder that effective gun control

legislation has been insatiable to the general public.

Despite the majority of Americans who support an automatic weapons ban, increased regulations, and universal background checks, congressional Republicans (and the few Democrats) choose stagnation – an autocratic choice. Their power has been so effective that there is almost a collective desensitization to news of shootings. There are more mass shootings than days of the year and guns are now the leading cause of death among children.These are all statistics and facts you know, you understand, and you grow numb to hearing. The fear of mass shootings has become a dystopian nightmare that neatly tucks itself into the minds of Americans. A human-made creation has become so unfettered and accessible, that it has single-handedly traumatized generations of youth even at the sound of a door shutting.

This unnatural aberration in the U.S. – that is, guns

becoming the leading cause of death amongst children – is ironically defended by the same party that promotes the “sanctity” of human life. The Republican party has effectively turned a “pro-life” stance into a central tenet of their ideology. The pro-life party sending only “thoughts and prayers” to the families of murdered school children instead of producing policies to prevent the tragedies from happening in the fi rst place is a paradoxical testament to the utter failure of American politics. After Uvalde, the actual Pope, Pope Francis, called for gun control and limiting access to brutal assault weapons. The Evangelical core of the GOP does not bat an eye however, because unlike the NRA, Pope Francis (who they deem as a direct line to God) is not cutting seven-fi gure checks to Mitch McConnell.

When tragedy has struck society, and especially when it targets the youngest and most vulnerable, the (modern) U.S. government has historically sought to eradicate the issue and preserve our youth. The Polio outbreak, for example, became one of the leading causes of death for children in the 1950s. When 60,000 children fell sick in the year 1952 alone, the U.S. government successfully implemented a series of vaccinations and strategies to combat the crisis. In 2023, however, where guns are the leading cause of children’s deaths, and AR-15s are massacring classrooms fi lled with 8-year-olds, Republicans instead pose with guns on their Christmas cards. The dystopian reality of guns is watching logic and reason vanish from the GOP’s minds and instead replaced with a thirst for power – and most importantly, maintaining that power. I want to argue however, that there is hope, and a stopping power. Corruption is no new phenomenon, and combating the autocratic leadership of the Republican party is feasible.

Consider Congress in 1964, when debate broke out for nearly 14 hours. Even when factions of both the Democratic and Republican Party joined in the fi libuster’s polarizing strength to kill the Civil Rights Bill, they failed. The vote for cloture was achieved and The Civil Rights Act passed, surviving the fate of being talked to death. After all, the fi libuster is merely a Senate rule, a rule that can be removed or evolved. In 1994 under President Bill Clinton, Congress passed groundbreaking legislation, and saw the most effective Assault Weapons Ban come to fruition. Today, grassroots pro-gun-control organizations like Brady, Everytown, Sandy Hook Promise, and Moms Demand Action only grow in their ferocity, their mobility, and most importantly, their funding and support. Finally, states are slowly becoming the wiser to pro-

viding gun manufacturers legal immunity through The Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act. In fact in 2019, the Supreme Court – under a Conservative majority – protected a lawsuit against Remington Arms Company. The plaintiffs of the case: families of Sandy Hook victims.

Discussing gun control is not a subject that should come with sugar-coating, dull promises, or meaningless thoughts and prayers from people who ironically ignore the wishes of the Pope. What is important and full of concrete, hopeful promise is the fi ghting political force that grows more angry as much as they grow weary of hearing news of mass shootings. If the failed Republican leadership continues to lay in bed with the NRA and hide behind the fi libuster, it is with the earnest hope that grassroots organizations, polls, and classrooms full of traumatized children will see to their political demise.

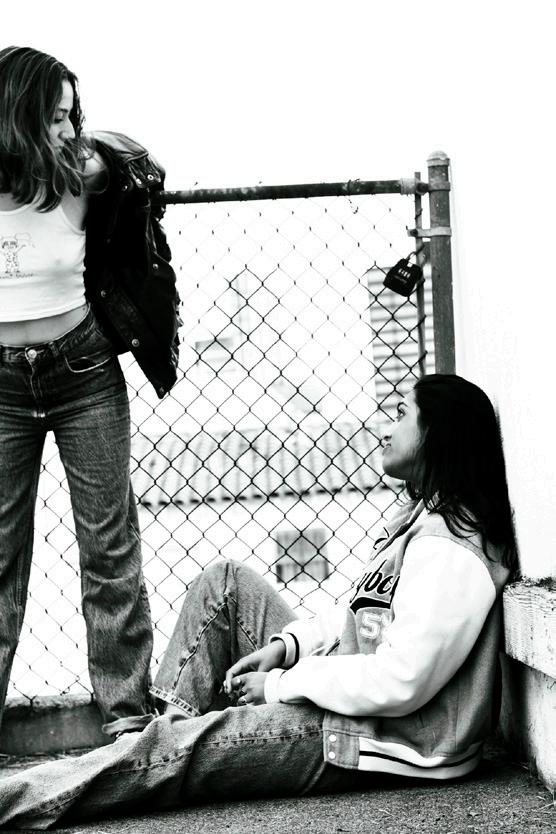

Models

Malvika Iyer

Bella Garcia

Makeup & Hair

Tia Barfield

Cali Perez Chavez

Stylist

Coral Utnehmer

Production & Props

Bella Garcia

Coral Utnehmer

Photographers

Cassandra Sanchez

Sophia Obregon

Coral Utnehmer

Creative Director

Coral Utnehmer

What is a child’s place? Many have asked and few have ever come up with a defi nite physical or even metaphorical place where children reside. The ambiguity of a child’s place arises because it can have multiple locations. Whether it be outside on a playground, listening to the radio, in front of a television screen, or scrolling on a tablet, children have found their place in play for centuries. Children’s view of the world is vastly different from adults, as they let their imaginations guide them into worlds unknown. As a kid you can pretend you are the king of the world at the top of the slide, or you can act out entire alternate universes with regular household objects. Children are visionaries who can take the ordinary and mundane and make it exciting.

At the turn of the 20th century with the invention of the television and the internet, a child’s place included watching morning and afterschool cartoons, and playing games on gaming consoles, apps, and websites. Regardless of its platform, a child’s place has always resided in their ability to escape the world around them through imagination.

A child’s place is not diffi cult to fi nd; however, it has become increasingly harder and harder to maintain with the introduction of new technology to what we think of as the typical kid’s space. The playground has now been transformed into various virtual playgrounds that do not abide by house rules. With virtual playgrounds being lawless we have turned what was once a safe space for children into a disorderly oasis. But the virtual playground has not always been this way. The jump from the physical playground to the virtual one was abrupt, but gradual.

Although the introduction of technology in children’s spaces is a relatively new phenomenon in human history, it is not as recent as most people would assume. The creation of the radio in 1895 brought a new interest in technology within American households. Looking at the Golden Age of Radio from the 1920s to 1930s, when on average 60-70 % of the American population owned at least one radio in their homes, there was already a substantial amount of airtime dedicated specifi cally to children’s programming. As found by The Guide to American Popular Culture, during the Golden Age, the time of 5 P.M. to 6 P.M. became known as the ‘children’s hour’ since kids would need to wind down for bed after coming home from school and playing outside. Sunday morning radio programs were often geared toward children because kids required entertainment in the morning before their families started their weekend plans. Both of these blocks of time featured storytelling that stretched across all ages and genres, from light-hearted moral fables for younger kids to thrilling action stories for older kids. As we can see from the radio, the introduction of a children’s space within adult technology is not as new as we are led to believe.

Similar to radio, television coincided with the implementation of a children’s space in the form of programming and games dedicated to younger audiences. The television, created in 1927, did not rise in popularity in the United States of America until the 1950s-1960s, post World War II. While only 9% of Americans owned televisions in 1950, that fi gure severely jumped to 80% by the 1960s. With this boom came the implementation of children’s programming blocks similar to those already on the radio. Television even adapted shows that were currently on the radio to be broadcastable to children, such as “Howdy Doody” on NBC in 1947. By the 1960s, there was offi cial children’s block programming for after school hours and weekend mornings on all three channels offered on television.

In the ‘80s, ‘90s, and the 2000s, television began to devote entire networks to kids full time. Instead of only kid’s hours and Saturday morning cartoons, now there was children’s programming 24/7, 365 days a year. Broadcast for the fi rst time in 1979 debuted a channel dedicated to airing children’s programming 24/7, Nickelodeon. The network saw its peak viewership from the 1980s-1990s. Disney Channel (1983) saw its peak

viewership in the 2000s. Cartoon Network (1992), focused on airing animated cartoons for children, saw peak viewership in the 1990s-2000s. Finally, PBS KIDS (1993) started as a children’s block (much like the “children’s blocks” mentioned previously) on the PBS channel, and then branched off into a separate channel in 2017. PBS KIDS saw its most popular shows produced in the late 90s to early 2000s.

The offi cial birthday of the internet is considered to be January 1, 1983. Similar to the progression of radio and television, we see children’s spaces being developed on the internet through the creation of the World Wide Web during the major boom of its popularity in the 1990s-2000s. While not exactly like its predecessors, children’s programming on the internet took form in many different ways. Whether it was television shows encouraging kids to go online to visit their sites to play games or to write electronic letters (now known as emails) to the stations to be featured on their programming, kids’ encouragement to investigate and explore the internet was forefronted by other media platforms. Child usage of the internet became so widespread in the United States that the federal government passed the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule (COPPA), which imposed restrictions on what age children could access internet websites without parental assistance or guidance.

In 1996, Adobe launched Adobe Flash, which assisted in playing videos and animating websites, allowing games for kids to start popping up all over the internet. In 1997, a website familiar to many kids who were in school during the early 2000s-2010s, coolmathgames.com, was established. Other gaming websites that were frequently visited by children in the U.S. were established in the early 2000s, such as kongregate.com in 2006 and miniclip.com in 2001.

The infl ux of child-dedicated space in the 1980s-2010 in overall larger adult spheres resulted in benefi ts to children and parents alike. Educational gaming websites like coolmathgames.com show strong positive correlation between the performance of children in reading and mathematical standardized testing and the volume of searches of the site. Additionally, coolmathgames.com was shown to be more frequently searched in low income households, suggesting the website provided enrichment learning to children in households that they may not have been able to afford elsewhere.

As we can see from the 1990s-2000s, there was no shortage of children’s places on mainstream television or the internet. These television stations and websites became a ‘home away from home’ for many kids growing up in the U.S. If you are anywhere between 20-30 years old like I am, you will probably remember staying up to catch the new episode of a show you really loved on Nickelodeon or Disney Channel. You might recall being sat in a computer lab with your classmates in the 5th grade and being told you can only visit a typing practice website or coolmathgames.com and thinking “who’s choosing the typing practice?” But if children’s spaces peaked in the 1990s-2000s, this suggests pivotal falls from the late 2010s until now

Technology has become a staple in our day to day lives. This century has witnessed the perfection of the smartphone, specifi cally the introduction of the iPhone in 2007. Following, screens that once kept people entertained in front of a television or a desktop became several times smaller. The smartphone’s appeal at the time was its ability to have everything you would need all at the tip of your fi ngers, with the simple reach into your pocket. The smartphone’s smaller screen produced a need for new media that didn’t have to be accessed through a web browser or a television, but through an application on a phone.

Social media existed long before the smartphone did; Six Degrees, which launched in 1996, is typically regarded as the fi rst social media site, though its perfection and standardization did not begin until the smartphone. Early social media sites that were curated for physical websites like Six Degrees, or MySpace, founded in 2003, required basic coding skills to change your profi le which drew out the average child away from the sites. This is a far cry from how we navigate social media apps today like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Tiktok; all changes are able to be made in the app with a simple press of a button. The switch from websites to applications on phones made social media increasingly accessible to the masses of people with smartphones. Advancements within social media technology allowed for social media to blossom — today, about ⅔ of the entire human population use some form of social media. Zooming in on that statistic shows that 90% of Americans use some sort of social media.

Social media is in its most accessible and popular age at the current moment. Like we have seen in trends within radio, television, and the internet, social media in its current boom has also become popular within

children’s spheres as well. A Pew research study shows that 97% of teens ages 13-17 in the U.S. report using social media sites like Facebook, Tiktok, and Snapchat. These statistics are not solely constrained to teens, as studies also fi nd that 65% of tweens, ages 8-12, hold an active presence on social media sites.

While there is no fully fl eshed-out empirical research on social media usage compared to television usage, we can see how the newer media is gradually starting to replace the old. TV News programming and channels used to be many people’s primary source for current events, but the Pew Research Center reports that 8 out of 10 adult Americans report getting their news often or sometimes from digital devices. Specifi cally, 48% of adult Americans report getting their news from social media websites or apps.

The switch to social media based entertainment like Instagram, Facebook, Tiktok, Twitter, and Youtube has provoked the social deaths of children’s spaces in other technological spheres. Overall viewership of television has seen declines since the late 2010s. For example, between 2017 to 2022, viewership for adult-driven programming like sport and news programs fell 19%, and unscripted television fell 34%. These numbers are shocking but they are nothing in comparison to children’s programming, which fell by 76% in viewership between 2017 and 2022. In 2021, Nickelodeon reported that it had dropped to 32% of its audience and it lost 71% of its viewership within the last four years (2017-2021). Disney Channel saw a similar trend in the year of 2021 with its viewership dropping 35%. Cartoon Network reports the same trends as it saw a 26% drop in viewership in 2021. As we can see, the children of today have begun to move out of the domains that dominated childhoods for the past 30 years and are turning to new forms of media like social media to keep them entertained. While there is dedicated kid space still on television, you will rarely fi nd a child in this child’s place.

Children’s internet is not faring much better. Adobe Flash was offi cially shut down in 2020. Unlike coolmathgames.com, which switched to HTML5 format to support its games, many such gaming websites shut down or went through extreme makeovers, leading them to look almost unrecognizable. Kongregate.com collaborated with museum conservationists to preserve its Flash games, but many familiar and iconic aspects of the website changed. The biggest loss to the Flash shut down comes at the hands of miniclip.com, which had to get rid of all their Flash games and now only have two games on the site: Agrio and 8 Ball Pool.

With television and online website gaming currently experiencing social death, there must be something that kids are turning to instead. If we follow the trend of new forms of children’s entertainment replacing the one that came before, a new phenomena is necessary to take the place of the television and the internet. The answer would be a resounding yes, but this new popular media might not be exactly “a child’s place.”

As previous trends have shown, with the popularity of social media comes children into these spaces, but unlike any previous technology, there were no spaces carved out for children. In all actuality, children were never supposed to have access to social media as these sites require business practices that would be illegal to carry out on children younger than 13. COPPA requires that websites not collect data for any persons under 13 years of age, but essentially all social media sites collect data from users. In response to COPPA, social networking sites and apps have never seriously considered the younger kids using their sites and have refused to create sites catered to that demographic. Although laws like COPPA exist, they are simply not enforced. Children as young as 8 are reported to use social media; even big hitters such as Facebook have called for greater expansions of their social media sites into tween audiences, illegality and all.

Additionally, in terms of what is considered a child it is clear that 13-17 year olds are still too young to occupy the same social space as adults. Children ages 13-17 are still developing their social brain and it is harmful to push them into the same domain as adults. However, since many kids have nowhere else to go for expression and entertainment they turn to social media.

So how are kids navigating this new media that both isn’t made for them and refuses to legally make space?

As we have seen, children as young as the babbling age all the way up to angsty awkward teens have a presence on social media sites. Many children have established their own spaces on social sites such as Youtube or Tiktok by posting kid related content like toy reviews or crafting videos. Unfortunately, some children are immersed into the adult space of their chosen site, either because of the lack of child-produced content or

because they have been recommended adult content. Most of the social networking sites currently run on an algorithm, or a set of rules and signals that automatically ranks content on a social platform based on how likely each social media user is to like it and interact with it. If your kid likes toy reviews they will most likely see toy reviews in their timeline. Algorithms also work based on what is currently popular on the site. This means that if something goes viral, like a music video, your kid will also get to see that too.

Considering how many kids falsely claim to be older than they are to receive access to media, it’s no wonder exposure to adult content is rising. Ofcom, the United Kingdom’s communication’s regulator, reports that 32% of children ages 8-17 pretend to be of age on social media to receive total access to the sites that would otherwise be restricted if they were underage. But even children who register using their real age are still subjected to being in adults’ spaces. For example, Meta, which owns both Facebook and Instagram, allows for children to have public accounts, meaning anyone can discover them on both these social media sites, and offers protection for minors only by restricting content that has been reported as adult content by other accounts.

The newest popular platform among children, Tiktok, has slightly stricter guidelines for minors’ accounts. Children with registered underage accounts are not able to appear on the For You Page, a random discovery timeline that works on a personalized algorithm allowing you to see videos from users you may not follow through accessing your likes (but also showing content that is popular on the site). People who register as younger than 18 cannot host livestreams, or, if younger than 16, cannot even send direct messages to other users. However, social networking regulations regularly fail at protecting children: in 2019 the Chartered Institute of Marketing found that 46% of kids ages 13-17 report seeing harmful content on social media.

In situations like the one we are currently facing, people love to point fi ngers at the very victims themselves. Discussions on whose fault it is that children are seeing adult content has risen in social media discourses. Some argue that it is the kid’s own fault for being in adult business and not staying in a child’s place which leads them to encounter content not suitable for children. Still, if we look at the situation closer, we can see how the infi ltrators are not children but adults.

The social media site known as Musical.ly, launched in 2014 and proposed originally as a child’s educational app saw its success in a child’s place. The education-turned-DIY-music-video-publishing-platform has always been for kids, as told by the creators. Even in its heyday, Musical.ly was known as the “kid social media.” Adults had Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. Children had Musical.ly, Vine, and Snapchat. Unfortunately, the child space that Musical.ly constructed was destroyed when the app was bought out by Bytedance in 2018 and used to create the powerful Tiktok we know today. Musical.ly was literally absorbed by Tiktok, transferring accounts and videos automatically to the new site. A site that was once known for catering to children was thrust into a social media platform that serves all demographics, thus virtually erasing what was a child’s space and forcing kids into a sphere of adult content.

While processes like the creation of Tiktok are not common in social networking spheres, the infi ltration of adults into a child’s place is not so rare. This is the case for “kidfl uencers,” children you see on YouTube, Tiktok, Facebook, and various other social media sites that produce content for other kids to enjoy. Just like other social media infl uencers, kidfl uencers work to not only make enjoyable content for their audience but also make money from their craft by marketing products to other children. Kidfl uencers are not a new phenomena; child stars have been around ever since the birth of the entertainment industry. What is particularly special about kidfl uencers today is their accessibility to their audiences.

Watching someone on YouTube does not invoke the starstruck feeling we get from celebrities in movies and television; instead, it feels like you are watching a friend or a family member, creating a sense of closeness. YouTube is a free service where you can see people create the content you enjoy unlimitedly. Kidfl uencers are marketed to kids and family audiences, but there is a dark side to the exploitation of children on the site. Content that was made for children and thought to be a child’s place is being infi ltrated by a slew of pedophiles. Typically, kidfl uencers across social media usually follow under two specifi c archetypes: family channel kidfl uencers and self-made kidfl uencers. Both are highly likely to be targeted by sexual predators because of their active presence on social media. Kidfl uencers who are a part of family vlogging content are typically forced to

appear on camera by their parents and used as cash cows to make money for their families. Family vlogging content raises many problems like child labor law and children’s right to privacy, and its biggest issue is its ability to expose children’s livelihoods to pedophiles. The other type of kidfl uencers are the self-made kidfl uencers, who occupy a bit more freedom in the content that they create, as they are not being forced by their parents to create content but do it because they want to. This form of kidfl uencing is susceptible to predators because the kidfl uencer accounts feature no adult supervision, so on regular bases these children are directly interacting with adults. Having to navigate the same social space as adults leads to pedophiles pushing the narrative that kidfl uencers are “mature for their age” and results in the sexualization, grooming, and harassment of children.

At alarming rates, we witness everyday stories of children’s media being sexualized by adults because of adults infi ltrating into a child’s place. Even popular content viewed by children, like crafting videos, is consumed by adults for sexual pleasure since it replicates a lot of fetish content.

YouTube, Tiktok, and other video publishing platforms have established a child’s place where kids are able to express themselves and use their imaginations to create content. However, because these sites are also places that do not solely cater to children, they have become unsafe environments for children to create and explore in. Unlike its predecessors like radio and television, there is no one curating what can be marketed towards children and who can occupy these spaces. YouTube falls in a weird ambiguous middle-ground of television and social media, as it is not really a social networking site, but it does produce a space where anyone can post videos watched by mass audiences. Although YouTube’s platform invokes confusion on its identity, YouTube clearly is able to reach child audiences. There is nothing bigger right now in the world of kid viewership on YouTube than family channels, slime making videos, and toy reviews. YouTube has become the main way children watch videos over any other streaming platform or television channel. Studies show that 53% of tweens and 59% of teens say they watch it the most out of all other entertainment options like television. A Pew Research study showed 81% of parents of children 11 or younger allow their children to watch Youtube content. But unlike television and radio that promised to solely provide children’s content, there is no guarantee that your child will stay in a child’s place on YouTube.

We are in a new age. Everything in our life has moved from televisions, desktops, or even laptops to phones and tablets. We have left children behind and unsafe. It is the adults’ responsibility, as it was years prior, to outline what a child’s place is — and they dropped the ball. When children begin to carve out their own spaces, entitlement results in adults forcefully taking over and occupying these spaces as well. Discourse around children in an “adult’s place” is emerging on multiple social networking sites. Many adults argue that it is not their personal responsibility to make sure that children do not see their content and that kids should stay in a child’s place. What they fail to recognize is that there is no child’s place because of historical adult interference. Whether it be the case of infi ltrating spaces, like we see with Tiktok’s absorption of Musical.ly or turning children’s spaces into sexual fantasies as we see across all platforms, adults of the internet age stay in children’s business. We judge kids for being on adult sides of platforms, when the way that the software works on these sites allows them to view the content we as adults can also see. While I agree that it is not our personal responsibility to make sure all children across the world are not viewing content that is inappropriate for their age, I do believe it is our responsibility to make sure that children have their own space to be creative and imaginative and entertained, just like adults have.

It is unfair that the children of this generation don’t have any safe spaces left. Instead of reprimanding kids for not staying in a child’s place, which adults have made essentially impossible, we as adults need to stay in an adult’s place. Instead of blaming kids for seeing adult content, we must push for more regulations on child cyber security laws and labor laws. Let’s start creating internet platforms that are made solely for children. Let’s start requiring that social media sites actually hold up their policies in regards to kids, and protect them in their social journeys. Let’s start caring about kids and a little less about ourselves. Let’s give children a child’s place again.

Few songs lyrically and sonically capture the vivid and fleeting sense of adolescence as perfectly as “Ribs” by Lorde. The rising synths that run through the track complement lines about “getting old” and laughing like children to encapsulate the fears and joys of growing up. I love how the song ages as we do too. When “Pure Heroine” came out in 2013, I was a precocious pretween whose version of “getting old” was training bra shopping and going to the mall unchaperoned, but now at 21 as a senior in college “getting old” is going to bars with my real ID and getting a Bachelor’s Degree. (Kelsey Ngante)

The Neighbourhood’s “Wiped Out”, Lorde’s “Pure Heroine”, Lana Del Rey’s “Ultraviolence”, and Arctic Monkeys’s “A.M.” are all distinctly early-mid 2010s alternative albums that capture the Tumblr era in its peak. All of these albums have black and white album covers, which harkens to a time when the peak of chic was posting a black and white filtered photo in a tennis skirt. “R.I.P. 2 My Youth” is just that brand of edgy, a 2010s pop song in alternative rock cosplay for burgeoning teenagers to mourn their lost youths.(Kelsey Ngante)

Hi, mommy issues! The wicked little lullaby that is Sonic Youth’s “Little Trouble Girl” captures what it is to be a girl becoming a woman. The performing, the expectations, the shame, the love, the lust, all of it. Sonic Youth, with The Pixies’ vocalist Kim Deal, tell the ever-familiar story of a girl struggling to reconcile the innocent femininity that is expected of her with “what she feels inside.” We’ve all been that titular “Little Trouble Girl”, caught between the pull to be good, to have that pleading, girlish innocence, and (Elsa Servantes)

4 5 6

Showcasing the inner turmoil of being 14, Alex G manages to encapsulate the experience of adolescence that is relevant to all genders. A very simple tune, the finger plucked guitar creates an atmosphere of nostalgia and longing, as Alex G, taking on the persona of Sandy, sings about the struggles of being a young teenager. The discussion of being taunted by peers and siblings is definitely relatable, and the repetition of many lines throughout the song represents feelings of perpetual longing that everyone has felt at the tail end of puberty. Being 14 isn’t easy, it is an age where you aren’t yet big but you aren’t young anymore either. The last verse of the song simply states “My name is Sandy; I’m 14 years old / My insides are changing / And right now, I just wanna grow up / I just wanna grow up / I just wanna grow up…” which so accurately represents complicated urge of just wanting to grow up; to feel at peace.

(Emily Haddad)

“Is anything as pretty as the past, though?” Fluorescent Adolescent asks this question as it teases the concept of aging out of sexual excitement. The song reminisces of a time when “all the boys were all electric,” uncaring and inconsequential youth, and empowerment through sexual frivolity, in contrast to an older age where “the best you ever had is just a memory.” The playfulness and glorification of spontaneous, youthful sex speaks to the way that aging is vilified and characterized as an unfortunate experience within popular contexts. Arctic Monkeys touch on how our adolescence appears fluorescent in our memory.

(Amber Stevens)Anyone born before 2005 has a video of themselves rapping “Super Bass” by Nicki Minaj somewhere in the photo booth archives. “Super Bass” has empowered people all over the world to step into one’s sassiness, illuminating the most playful versions of their personalities. No matter what was happening, singing “Super Bass” had the power to make everything feel alright, even if your parents were getting a divorce in the room over. (Izzi Fraser)

“Seven” tells the story of young friendship in the midst of strife, and escape from corruption through naive imagination. It depicts innocence hauntingly, as a commodity which protects against reality. The line, “before I learned civility / I used to scream ferociously” demonstrates that we lose the rawest part of our humanity when we trade our youth in for worldliness. Growing up demands a shift from perceiving the world as a shiny playground to perceiving it as a place where one must succumb, begetting the question, when we sacrifice the purity of novelty to time, “are there still beautiful things”?

(Selena Perez)

This song depicts the torment of an ambiguous relationship’s death. While it is not blatantly about youth, the song utilizes elements of youth as a vehicle for the idea of loss, making it inherently analogical to the theme of farewelling childhood. The artist mentioned in an interview that the song was intended to sonically mimic a lullaby or nursery rhyme. It provokes images of a rippage from the cradle of what once felt secure. The song holistically illustrates clawing desperately for scraps of the past’s bliss, just as adults long hopelessly for versions of themselves that knew no worldly damage. (Selena Perez)

This song is nostalgic both tonally and culturally. It was a coming-of-age backtrack for an entire generation, originating from Hannah Montana and maintaining significance in modern media. In it, a teenage girl fondles memories of a parent lovingly ushering her through a bedtime routine. Ironically this routine is being interrupted in the name of new beginnings, and the past is being laid tenderly to rest. The melancholic tune is timeless, and puts a tear in my eye at every stage of life. I chose this song ultimately for the way it showcases the metamorphic nature of girlhood, childhood, and caterpillarhood.

(Selena Perez)

10 11 12

This song encapsulates what it means to give away your “golden years” to someone who makes you feel all the emotions on the spectrum. This song can also be seen as giving your all in your youthful years to any sort of cause. We regard youth as a precious thing in society because it is time sensitive so giving it to someone signifies a big commitment. While youth is the happiest time of our lives it is the shortest. “My youth is yours,” while in the present tense, gives a nostalgic vibe as we look on our life experiences and encounter the highs and the lows of commitment and sacrifice in our “golden years.” (Alexus Torres)

This song describes the radical nature of teenagers and their ability to create change within the world. If you have ever been at a protest or if you have ever seen a hashtag trending on twitter you will know that youth are the main mobilizing efforts of social movements. This is not a new phenomena however because as long as social movements have existed there has been some teenager on the front line of the cause. As the song describes, adults’ categorization of teens leads them to undermine their abilities but youth has the ability to make things happen. Teenagers are scary because they are relentless in the fight. Keep scaring them kids! (Alexus Torres)

The warmth of a mother’s hug can heal all. Lauryn Hill’s cover of Frankie Valli’s “Can’t Take My Eyes Off You” reminds me of twirling in the kitchen with my mom after a hard day at elementary school. “Dance it off,” she’d say as we’d sing, “you’re just too good to be true, can’t take my eyes off of you.” This song has been a staple throughout my youth, getting me through the trials and tribulations of girlhood one twirl at a time.

(Izzi Fraser)

Anastasia Beverly Hills Luminous Foundation: I squeeze out the beige viscous liquid onto a fl uffy brush and start dabbing the product onto my skin. The shades don’t quite match, but it was the best I could fi nd at the beauty store. The color is somewhere between orange and tan, and while it does a decent job of smoothing out my complexion, I can’t pretend that I’m satisfi ed with how my skin looks. I am lucky to have begun wearing foundation when brands are attempting to be more inclusive in their shade range, yet fi nding products for my skin tone always presents itself as a Herculean task where even the professionals in large beauty stores struggle with matching my darker shade. I feel even more disheartened when the advertisements plastered on the large glass windows emphasize the allure of having “milky white” baby skin, soft and smooth, and the products that will help consumers achieve that goal. As I return home with a passable foundation shade, I spread a thick, even layer across my face, and sigh with disappointment as the fl aws and bumps are not quite erased as the advertisements claim, and the darker peach fuzz that covers my cheeks is even more obvious as it is now covered with this coat of paint. But instead of dismissing the foundation as being unsuitable for my skin, I know the failure is in my face, so marred with problems: texture, acne, facial hair…for these are the reasons why my skin doesn’t look like the models plastered on the glass windows of Sephora with their skin being so devoid of imperfections as if they retained the youthful glow of their childhood, a toddler’s supple skin. No. It is my skin, one whose problems not even full-coverage foundation can fi x. The problem is with me, and not with the product, because if models can have “milky white” baby skin, why can’t I?

Nars Creamy Caramel Concealer:

I apply a swipe under my dark circles, acne scars, stubbly chin, and hyperpigmentation. The fi rst makeup product I purchased was concealer, as it was absolutely crucial that I fi x my skin discolouration immediately. I refl ect on the very word, “conceal - er”, which suggests that there are parts of us that must be kept hidden from the outside, parts of us that are undesirable and require elimination. I’ve never thought of myself as getting old, but as I blend the product, I notice it settling into the creases around my eyes. Staring at myself in the mirror, I scrutinize the parts of me that I thought were just normal and now realize that the concealer is hiding signs of aging. The wrinkles on my forehead, fi ne lines around my mouth, hyperpigmentation on my cheeks, and acne scars that occur as we live. We are born with faces that resemble blank slates, and as we live we become marked: our hard work, adversities, and growing pains are all etched into our faces, marking the transition from youthful beginnings to adulthood. Stories are written in faces, in the wrinkles that surround an elderly woman’s eyes indicating she loved life and lived it with joy and smiles, or the dark circles around a student’s eyes, the result of long hours spent in libraries working to pass their exam. If these marks are proof of the living, proof of the trials and tribulations of life, why must I conceal them?