6 minute read

The Unfinished Conversation Cat Dunn

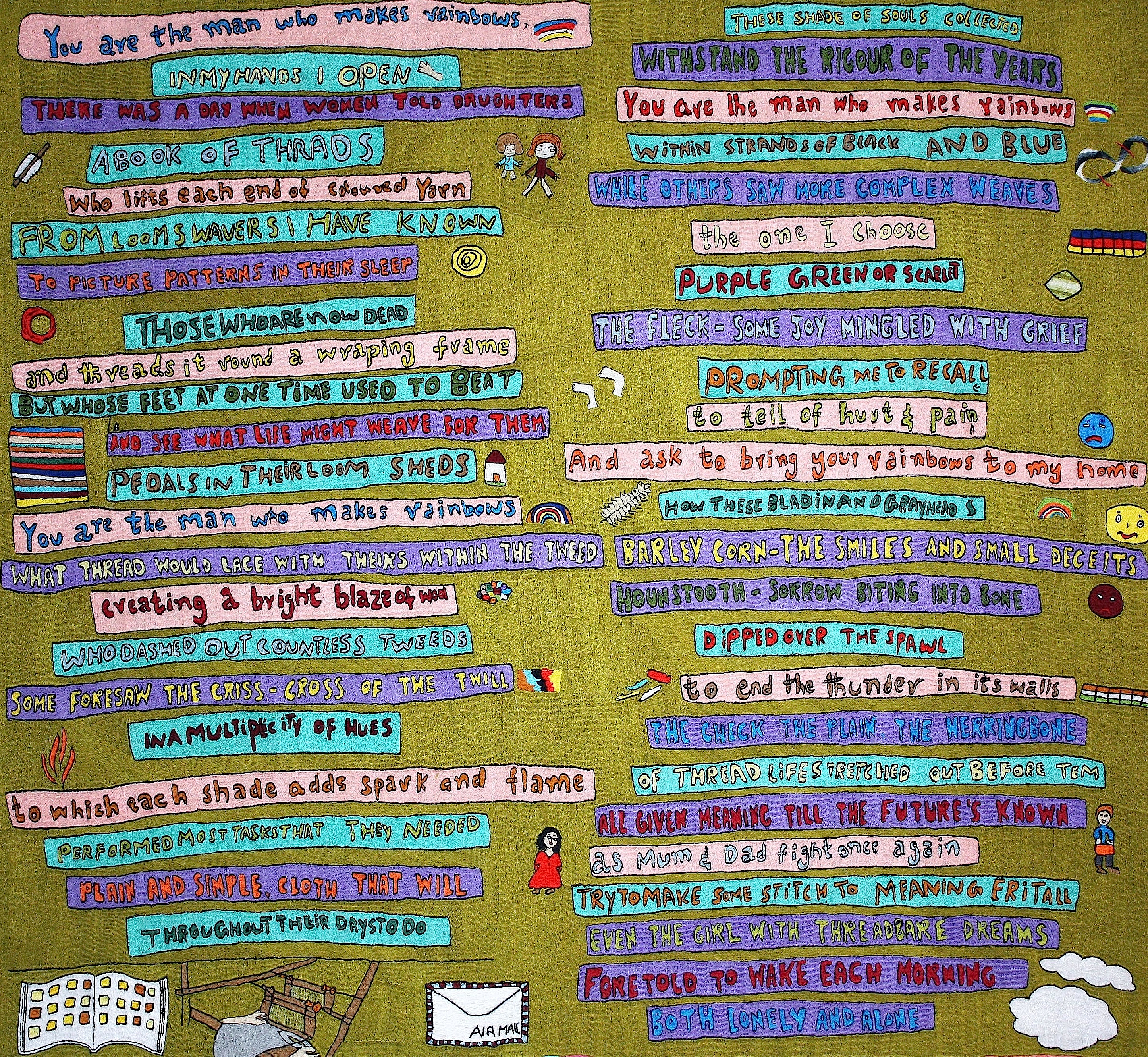

Crafted Selves: The Unfinished Conversation is a multi-layered, dynamic, mixed group exhibition held at St Andrews Museum and Kirkcaldy Galleries in 2023 and 2024. The show consists of the work of 13 artists, with artworks ranging in genre from paintings to installations, from ceramics to mirror work to textiles, from written pieces to moving image films. The artists range from experienced to early career, all incredibly talented.

The title is from the continuing discourse with the artists; what does it mean to have a Dual Identity, and how is this sense of self-reflection in work being made by Scottish craft artists today? With the artists based throughout Scotland, contemporary Scottish Identity will inevitably be a part of the conversation. From lived experiences and histories that are experienced as pain and anger, the process of making and creating can express this pain but also bring a sensation and expression of joy and celebration in claiming Dual Identity.

Craft is often seen as an activity, pursuit or occupation involving making things by hand.1 Historically, it is an action which requires a particular set of skills and knowledge of skilled work and is usually applied to people occupied in small-scale production of goods. Designing, creating, and hand-making a crafted object connects the maker profoundly and personally to that object. Each of the artists taking part in the exhibition uses layered and complex elements of craft to create compositions that offer a unique iconography and hybridisation of references. Elements of historical and contemporary diverse cultures merge and create anthropological and dreamlike spaces outside of the geographic location, through which an artist can question the generational and geographical codes that create their identity.

Each artist balances their different genealogical cultures, which is sometimes a struggle. Nevertheless, they seamlessly mesh when these elements come together in their artwork.

Having more than one home and a hybrid point of origin is no longer unusual. Social Identity shifts into a more nebulous network of geographical and geopolitical locations, feelings, memories, and oral histories in our increasingly globalised world.

Art does not have to be constrained to one medium. In the same way, artists can embrace their multiple cultures and identities. For example, Crafted Selves allow the artists to explore their identity through self-portraits and symbolism in works of art that relate to ancestry or culture. Crafting and art objects intersect all cultural domains: economic, social, political, and ritual. Craft goods are social objects that assume importance beyond household maintenance and reproduction. They signify and legitimise group membership and social roles and become reserves of wealth, storing intrinsically valuable materials and the labour invested in their manufacture. Specialised craft producers (artists) are involved in creating and maintaining social networks, wealth, and social legitimacy. Artisans and consumers must accept, create, or negotiate the social legitimacy of production and the conditions of production and distribution, usually defined in terms of Social Identity. The nature of that process defines the production organisation and the social relations that characterise the relationships between producers and consumers.

Without attention to artisan identity, our reconstructions of production systems and explanations for their form and dynamics are destined to be unidimensional and unidirectional, lacking in vital elements of social process and behaviour. Art can be seen as a stimulus for social transformation and political change. Identity in modern art is a broad and exciting theme, allowing viewers to gain new perspectives and understand other people’s lives. For the artists who draw inspiration from their identity, the work becomes a podium for exploration, expression, and connection.

Social Identity is the way we perceive and express ourselves. Factors and conditions an individual are born with — such as ethnic heritage, sex, or body — often define one’s identity. However, many aspects of a person’s identity change throughout life. For example, people’s experiences can alter how they see themselves or others perceive them. Conversely, their identities also influence their decisions: individuals choose their friends, adopt specific fashions, and align themselves with political beliefs based on their identities. Many artists use their work to express, explore, and question ideas about identity.

Of course, everyone has, in a way, multiple identities - you can be a wife, daughter, mother, sister, son, husband, uncle and so on. It is what the world sees and where society places you at a particular moment. Some individuals’ physical, social, and mental characteristics can define Social Identity. For example, social identities include race or ethnicity, gender, social class and socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, (dis) abilities, and religious beliefs. Dual Identity is defined as identification with both one’s ethnocultural minority in-group and one’s society of residence. 2 This class of identity recognises subgroups’ differences and creates an overarching category. For example, group members can conceive two distinctive groups (e.g., White, and Black) within a superordinate (i.e., American) social identity.3

Even if the term Dual Identity is a specific term related to ethnocultural background - we are exploring other dualities as well; and, as such within the exhibition there are artists who are transgendered and artists who define their disability as an identity.

We currently stand in a moment where Britain goes back and forth, arguing about immigrants and people of colour’s role in the identity of Britain. Yet, I feel that as a result, Britain can become a place of togetherness through shared histories.

Scotland itself is undergoing a cultural shift as it repositions itself in the wider world, with Scottish art at the centre of the current discourse about Scottish social identity. For example, in 2022, Scotland was represented at the Venice Biennale by Alberta Whittle, the first black woman artist who openly claims to have a Dual Identity belonging to both Barbados and Scotland equally.4

Art and craft can express aspirations, values, and national character.

Cat Dunn - 2023

An expanded version of this essay can be found at www.fcac.co.uk

1 Ratten, V., 2022. Defining craft making. In Entrepreneurship in Creative Crafts (pp. 29-38). Routledge.

2 Platt, L., 2016. Is there assimilation in minority groups’ national, ethnic and religious identity?. In Migrants and Their Children in Britain (pp. 46-70). Routledge.

3 Schaafsma, J., Nezlek, J.B., Krejtz, I. and Safron, M., 2010. Ethnocultural identification and naturally occurring interethnic social interactions: Muslim minorities in Europe. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(6), pp.10101028.

4 Wendt, S., 2023. All the World’s Histories: At The 59th Venice Biennale. Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, 52(1), pp.120-135.