Vital

Signs and other poems

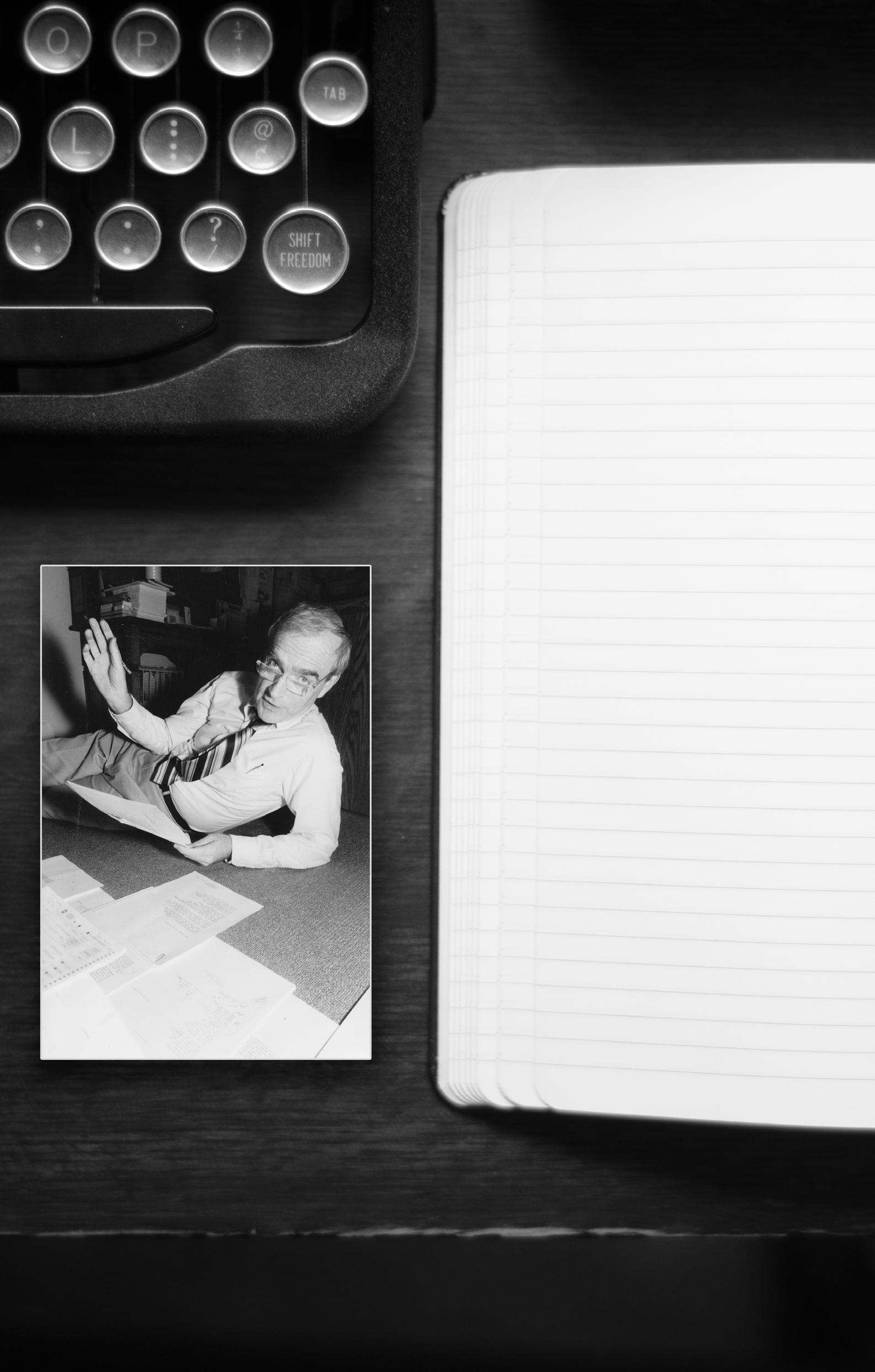

When I think about Dr. Dillon, the word that comes to mind is passion. While attending Flagler College from 1994-1998, on the fourth floor of Kenan Hall, in the corner classroom, I was privileged to be taught by one of Flagler’s greats. Dr. Dillon shared his love for literature with his students. Whether he was running up and down the steps or sprawled across the floor, whether he was discussing a trilobite or Milton, Dr. Dillon oozed passion. It was something his students could see every day in his classroom; indeed, it is something we can feel—even twenty years later.

During the course of our lives, we sometimes have the great fortune to meet those who inspire and bring out the best in us. Dr. Andrew Dillon was a college professor who truly inspired me my freshman year at Flagler College. He inspired me to read poetry and Shakespeare, something I had never done before. During my four years at Flagler, I took every course that he taught and ended up with an English Literature major, initially having planned to major in business. His courses also taught me to be a better writer, which has served me well during my career.

I recall days in his class when he would be discussing a scene in a Shakespeare play and suddenly jump up onto a desk and fight a battle with his imaginary sword quoting the character verbatim, completely engrossed in the moment. Or, days on a bright spring afternoon when he would announce, “It’s too nice to be inside!” and he would escort the class onto the grass lawn for our lessons in the great classics. And, this was well before Robin Williams starred in “Dead Poets Society.” I feel truly honored to have been taught by Dr. Dillon. He has been an inspiration to many, many other students like me, and I know we all are better to have him in our lives.

— Rachel Wootten Flagler College, Class of 1998 — Charles J. Tinlin, County Judge, St. Johns County, Florida Flagler College, Class of 1979I’ll never forget sitting for my first Dr. Dillon test in English Literature. I was a “good” student who never missed class and who did my reading, but as I uncomfortably squirmed and wriggled around in my seat hoping answers to these questions would present themselves to me, I distinctly remember his advice to us on how many times we should read the literature: Not once, not twice, but three times, to really understand what the author was trying to express. Now, as I literally sweated through this exam, that advice came roaring back to me. I learned the hard way on this one and never forgot it. I hadn’t been an English major, but soon I was another eager and willing sponge in the classes of Dr. Andrew Dillon, ready to soak up more of his witty and wonderful ways of bringing literature to life. Dr. Dillon opened my eyes and my mind to the challenges of Shakespeare (Yes! I can read, understand and enjoy this!) and to the fresh pen of Walt Whitman. His love of Whitman transcended the room for each of us! I still have my books and turn to them on occasion to relive the magic of those late morning classes on third floor Kenan Hall. I am there as I write this now. So “Of life immense in passion, pulse and power, cheerful, for freest action form’d under the laws divine, the Modern Man I sing.” Thank you, Dr. Dillon.

Andrew Dillon’s poems take readers on a journey through life, love, and facing one’s own mortality. Whether he is musing on King Lear while admiring a friend’s dedication to serving the homeless or lamenting a marriage that is eroding, Dillon’s poems are insights into the complexities of being human. Vital Signs is a collection of poems that are deeply personal and full of passion, joy, and sadness over the fleeting time we all have.

— Garrett Riggs, Writer and Editor Flagler College, Class of 1990In response to events, Andrew Dillon awakens dignity and feelings of happiness, wonder, and love—the poetry, the music of how the human heart works.

— Carl Horner, Professor Emeritus, Department of English, Flagler College, 1988-2011 — Beth Shaw Masters, Flagler College, Class of 1987To the one whose generous spirit, clear thinking, and warmth of response, always bring me to feel the cheer and the love that are life itself.

Fish will be leaping in the marina behind me with silver flashes like a leap out of everyday language, and for a link to true feeling, I’m off to flip out of dark waters where poems arise.

Andrew DillonJust yesterday in Publix, I asked an old guy before the huge wall of beers, if he remembered Rheingold beer. He did, and we began to sing the song from radio in the 50’s: “My beer is Rheingold, the dry beer; buy Rheingold whenever you buy beer;” —a moment of shared feeling for the long past.

I must be open somehow, because only a small bonk of metal on metal through my cargo shorts, saved me from dropping them in the washer and drowning my cell phone in hot water. Imagine the regret, the feeling of foolishness that would have flooded over me —a true loneliness of folly.

Yet no feeling I have is better than when you come in the front door, for our evening has begun, and often we sit out on the porch in the late light, and I enjoy the news of your day at the college, but there’s more to feeling than happiness, for its touch is my release, my panic, my art.

I get up at the five o’clock hour, unlock the front door for you to come in on your way to school, a vital sign as you enter, for I’m usually on my second cup of the frothed milk and coffee, you taught me to make, yet your talent is solving problems mine exaggeration.

I claimed to Darien on the phone that I can do a 15 minute King Lear, on his awakening to a sudden feeling for the poor on the rainy heath, those in “loop’d and windowed raggedness” who haunt the storm.

I’d like to get 15 minutes of a class on this topic of awakening to see if I can still pull it off. Does my style still work? I’d like to catch a wave like a surfer, an insouciant lad grown old, yet feeling is the prime breath of being.

You stop by from your place most mornings on the way to work, and I realize how much I care about your bright smile, your look of delight, for your psyche tends to say yes as if cheer were a part of your physical make-up; mine hesitates, or hides out in a no, yet we click, as if ready together to hope and to solve. Our mystery is harder to understand, yet love of you is the charm of my life—even if I need a cane to get out of the car, and use anti-anxiety pills of a low power to be able to sleep.

We learn at the cancer doctor’s that he may come to have a new immune-cell therapy test soon— I assume there’d be no more groadymaking chemo but a new idea in training the immune cells to spot cancer and go kill tumors, at last, so maybe I could become human again— perhaps die of something else— a curiously happy thought, for there’d be more time to be with you, Vivaldi’s music, and the great ease of love’s unexpected happiness.

In early October, wild geese are calling to each other constantly as they sweep by, dark bodies clear against the partly clouded sky.

Geese, October here is sweet— stop and stay awhile that I may hear the music of your honking: hoarse, a little anxious, persistent as love itself.

For twice a year is not enough to hear from high above the raucous words of creatures with no other question but “are you there my love?”

You were patient about the three e-mail copies of one poem I sent you, for I was lost in the ineptitude of not being able to get “sent” to show me the attachment as it would do only days ago— something has changed—a little window is shut. Of course, I can see the poem back in its own file, but the computer is always as unromantic as Amazon.com that hoists you into its digital world as pure and breathless as the stars.

When I last saw you, Darien, we were human— not a shimmer of e-mails—talking together at the college’s holiday party, where the Darien I know, perceptive, alert—luminous—told me of her decision to teach Gatsby in several different classes, for Gatsby’s essential illusion about Daisy yields waves of wonderful hope. He’s an entrepreneur of the heart, exchanging all time for a word— that American feeling. We both often return for a dip into the life between Gatsby and Daisy, for the shadow of fate can’t dim vitality’s glow

And our love of how words reach up from the page made us teachers, since the world needs to share what’s intense, healthy and true—if dangerous. Moreover, we’re briefly allowed an extra life, for Daisy and Gatsby sit on the couch of his mansion, even now, full of that “intense life”—an ache of happiness everyone needs. For teaching is such good fortune if you follow your heart, and even the students who don’t do the work find a true vision of life in the pure action of you being there, teaching.

The Dipper is balanced over the North Star, where the elegant handle and cup shake a prayer of being alive out of my heart, as it pours a nutrition of wonder on my defenseless head.

And I remember you— precise, and missing nothing, among the other students seated on the stair-like levels of 419 in Kenan Hall.

My essential truth was being in cahoots with students, for we were delighted together with the life-giving words of King Lear, when he stresses feeling as the emotion he lacks and spends the play learning, loose on the windy plains of great language.

However, such ideas are easy to pass over on a first reading; that’s why I was so noisy, since I had only one chance to climb the ramparts of Elsinore to find Hamlet work his witty way through a mesh of murderous events.

It all rises again as I think of you, for I was given a chance to live the passionate life of Shakespeare’s fresh genius of being, as it became us all, while we shared a class hour in Kenan Hall.

It’s fortunate the mail comes at eleven, because I always wonder what’s waiting in the box, for poems fade before the world’s raw power. How can I write with a property tax letter in my hand? But this time there’s a letter from a former student, saying, “poetry can be a balm like no other,” and her harmonious phrase opens a door to a song-like desire to get something said— that’s some sort of nutrition of words, calling up what’s hungry, ambitious, and true.

And I write my student back, since my energy didn’t fade at noon, and responding might clarify me, for surely yearning is at the heart’s root, and I was fortunate to spend my Shakespeare classes surfing on emotion for happy years, and my student knows all she needs about poetry’s power to animate, to heal, and round out the nervous work of the heart.

They’re like acrobats swinging from room to room; one-year-old Owen finds my cordless phone and gets a call through, for someone calls back to find out what’s happening.

Lucy begins to dance to the music of Swan Lake on her mother’s iPod, gliding to the sweeps of swans flying in, because she knows the haunting lake of the moment— leaving me aware that you must keep on learning, or there’s no dance to your life—no calls from the universe—at last— to find out who you are.

Before the house, looking at the stars, I feel the drive again to learn how to live, for I’m charmed by a video of my grandson using a chair to pull himself up on his own—how old can you be when you see young Owen stand for the first time?

When I’m in the shower, I hold myself safe by the two grab bars recently installed, holding on with one unsoapy hand to keep from falling. Owen, I saw you on a new video pushing a toy cart with wheels and a high handle across the carpet; you’re hooting in triumph because you’re in control—essentially walking— yet you fell easily and got up so fast.

When I’m on the floor, I’m stretching, or lifting little weights to see if I can stay from being wobbly when I go for a walk; everything planned—no spontaneity, but your first steps on the latest video show you walking like a sailor in snow across the living room floor to leap into your father’s arms with a look of delight at what you can do, and that look will come back some day when a big game is won, or when you first realize you are in love.

As I put back the milk, There’s Lucy on the ‘fridge door, sitting in her car seat with her hand on one side as tho’ paused from waving at the crowd— she has a benign smile, even mildly bemused, or is it merely the drive that pleases her?—

yet I think Lucy is charmed because she is charming, yielding me a true moment, between the brewing of my coffee and the drinking of it in the presence of her smile.

I imagine all the genes designing you, and suddenly I see a bird’s eye view of Manhattan in the 1850’s—it’s what your great, great grandfather saw as the boat from Ireland hoved into New York harbor. It was 1857, and he was only 12, so he must have been met, but all I know are the bare facts of his landing, his age, and his name, Richard O’Connor.

He was my mother’s father, but no photograph of him survives, except an echo—now expressed in your arrangement of genes, for he still figures as a life-link, who faced that day the glory of Manhattan, all 5-story buildings, no skyscrapers yet.

Some sunny day, Lucy, you can visit the tip of Manhattan, finding Wall Street and the run of Battery Park, for Richard O’Connor first walked Manhattan’s streets right here, where your genes may chime as mine have done at Trinity Church’s momentary cry of noon, where Wall meets Broadway, for time may be wordless, but it speaks a clear language of the flesh.

Now as an inner voice urges you to learn how to walk, one day you may find those streets where some of your genes have walked before, where segments of your body may once have been dazzled—for you’re a river of life, and your name is light!

Someday Owen’s dad will slip in the DVD that has the home movies of the family in the 1930’s, and Owen can see the first Dillon in America, long after he got here, laughing on a summer porch in Southhampton or maybe Easthampton.

It’s the only image of him that’s survived; no photos, no stories, except my aunt said he was always cheerful— a nice fragment to know—a happy, laughing king of DNA.

But when my copy of the new DVD of these home movies gets here, no Joseph Dillon on the summer porch in the Hamptons survives. He must have been in the movies I did not save, when we viewed them in Boston nearly 45 years ago, but he’s there with Owen on the settee of my imagination; it’s synapse to synapse, singing along in black and white memory.

Owen doesn’t care; he studies the cheerful old man with the same interest he studies me when I’m around, for Owen is a cheerful baby— responding to cheer—so far away—so near, for Joseph Dillon landed in New York Harbor in the 1870’s—a set of genes arriving in the land of success, and how charmed Joseph Dillon is at this sprig of the tree and his sister Lucy, who enters the scene doing twirls from ballet, and tossing flowers representing ambition and success, for off the boat is always America, the flourishing dream.

There he is holding two giant Lego-like segments with many prongs to fit together, designing the next bridge— suddenly, he’s a foxy youth of one year who has left his calm CEO babyhood behind, a fabricator of practical dreams.

There he is smiling and showing new teeth as I study the copy I made; I don’t know how I did it, but it printed anyway off e-mail, new to me, for I was inventing too in a tiny Owen mode, since we only get where we’re going by our genes, holding mutations of change through the generations.

So children with firm little teeth—like Owen smiling, have a certain determination—a cheerful power— even now, for his Lego is ready to build the causeway to something digital and gearless under the stars.

My dad was a great marcher like Orion to whom my liturgical hands would offer words in a spiritual dark to pray the world into life by seeing and feeling, yet I find the giant in the tiny success of opening the stuck refrigerator door by slamming it hard from being urged a little way open, thus freeing the vegetable bin to the applause of timeless generations.

We’re born into an egocentric mystery of wild longing for the world: the essence of the leaf is flinging its self, self, self into the sunlight, yet when my eleven-year-old shows me his report card with a nice sprinkle of B’s and C’s, on the opposite side there hangs a banner of S’s from September to May—

imagine a perfectly satisfactory child, imagine how he takes the slam out of death’s total wash, imagine hugging the real stars who don’t spell out answers just hum a little.

It would rip me out of the primitive pleasure of how the clock of the universe moves: too much stuff—too many exhaustive distances and amazing pictures of stars coming to be. My route is to delight in the obvious like the dime-sized spot of blood on the kitchen floor, an effusion that overwhelmed the Kleenex last night in the dark when my nosebleed was quicker than I was, yet it’s a little red star in memory now as I step out the back door for a last look at the Dipper poised over trees, because I like majesty— the simple arrangement of seven stars suggests a mysterious giving, a grace pouring out of a pure accident that I must imagine has a paradoxical purpose even as I do. My religion has become breathlessly spiritual—under what’s up, when I come out at five, yet my resolution is raising both hands under the stars.

After brushing my teeth, I look at my reddened face lit up by chemo’s retreating power, as if this were the moment I’d have before death to say whatever truth I know is what I know now, even tho’ I still feel there’s music for more— more blood on the floor.

Yet I live in a retirement community, where death is the usual harvest, but I don’t want to go, I want to teach on: Lear for feelings awakened—Paradise Lost for passion, for charm, for the terrible music of the fallen, yet who else can sing?

You called, and I walked to the quiet back of the house in the dark to hear of your day. Since you’ve had a big week at work, I wanted to take you to dinner on Saturday night, but you said it was the Georgia-Florida game, and the town would be flooded with visitors.

I offered to bring a good wine to suit the dinner you plan, and you suggest a bordeaux at the store on King Street, a wine that’ll offer a hillside of sunlight in the warmth of its taste, especially in the early dark of October.

Soon, I’ll be moving along on US 1, then down Malaga, with a right on King to the store’s parked line of cars to find that hillside’s inner glow to bring home to your place, for I’m not young any more, except when I forget the stiff back of years in the immediate cheer of your eyes.

We enjoy the gold light of late afternoon and let ripples of words carry us along to the country of being young; Vivaldi is on Pandora and opens a harmony we know well, for it’s as fresh as it was in New York, when we played The Seasons again and again on records I still have but never play alone.

I don’t even feel foolish in asking you to call me now on my cell phone (while in your living room) for I’ve lost calls by pressing the wrong little bar—so we talk on our phones since I’ve found the correct bar, and here we are accidentally enacting a distance between us, yet freeing me, for I long ago learned how to make calls; that’s me! For there’s no life without the drama of the love I remember, no vision, no vistas, no drive to embrace, leaving me open to an assault of feelings, as close to being happy as I get—but real.

How much I’d like to stay longer, feeling awkward although I feel good, for you plan a dinner of triggerfish next Saturday, and ask me back a little earlier, to avoid the early dark of fall.

Looking at you, with dawn’s light just showing, I imagine I could say something to heal us, breathless in search for the right words, for when I bring roses, you’re so pleased you get out three vases, so there’ll be some on the dinner table, some between us where we sit by the windows, and, once, one to go up to your bedroom at the top of the house.

Suddenly, the living room became as big as the world, and I stood there while you carried off that love-of-my-life rose as if there were a dimension—somewhere close— who knew who we were, always ready to take over.

I’m sorry—doubly sorry, I broke your heart, yet fractures heal, and I still hope, even as the long gold light of summer is eaten up by dusk— that when we go off to separate rooms, our regret includes somehow the residue of love.

At one point, on the South Tower stairs, Rick Rescorla phoned his wife, asked her to stop crying, and said “I have to get these people out safely. If something should happen to me, I want you to know I’ve never been happier. You made my life.” Later, he went back upstairs, and was lost in the collapse of the tower.

The welling of feeling I sense at reading “you made my life” is a moment of clarity so complete that the flooding of my eyes is what happens when we find how desperate love is to tell the truth.

It says what I feel about you long before I can think—a truth I can’t say when we’re out enjoying a dinner— no, it’s a truth of disaster, of cell phones, of crowded staircases, even when the sudden lurching of the building bodes only more danger, for, inside that last cavity of time, he could speak what forms my tears now, when I, too, breathe the searing wishes of love.

We listen to Vivaldi and Bach just as we did years ago, and I admit we talk through it but are aware of the sweet energy of Vivaldi’s constructs or Bach with his harmony of foreknowledge, as if the world were his instrument.

And, yes, we’re not playing Judy Collins any more but I can hear her from all the way back in New York—just fragments of Scarborough Fair, but real after all these years and, like love, resilient, for I love music with you but home I don’t play anything— maybe I’m working on a poem—that is writing until something real enters the room from the huge world inside,

but you put on music when I arrive, a flow of sensation like the charm of a glass of wine, for I’d ask for the Vivaldi selections you have, if you did not choose them yourself, and when I’m with you I feel music suggesting a happiness as real as it ever was, but when I’m away I don’t seem to care— yet with you every metaphor is high fiber, and has the zing of love’s paradox: that two may be one.

You drive home in your new car and call me on the way to practice with the phone that’s newly set on the car frame, which gives your voice an extra baffle of distance, yet you come in perfectly clear.

Later, the vividness of your voice rises in my mind, for I had imagined last Thursday calling you on your cell in the thick of a Board meeting, just to hear your voice.

In the hallway of my mind, you said, “I’m in the middle of a meeting, and it is tedious, but I love you, even if I can’t talk.” It was a true moment, even if only an invention, as if penning a poem to discover the wound of happiness could be healed by a residue of feeling—

but still I think of my driving in or your coming out to cook dinner, the whole politics of sorrow, yet it’s like your car phone to a lost country where I can always be found.

When I called last night your phone’s recording sounded a little tired—or was it some regret at the way we live now in different houses? Since your blood pressure’s gone mysteriously high and with the sudden arthritis in my back, we have warnings that time is pushing us along.

Our next meeting is a wine tasting, where you’ll try a little of each, but I’ll sneak back to the champagne— why not?—a free riff of that wine associated with happiness, with receptions in New York: like the time we were late to a wedding, and I meant to say Brick Presbyterian Church to the driver, but came out with Prick Chestpyterian Perch, and we laughed all the way up Park.

Recently, you mentioned the Oak Bar at the Plaza, where we once sat in the warm dark roar of the place, huge windows looking out on a blizzard over Central Park, and who would not trust that such charm was forever?— for we were deep in the oak-paneled room with the vital din of talk and the sounds of silver and ice around us—so sure of each other, beyond any storm.

Tonight, you call to thank me for a gift I’d left for our wedding anniversary: a bottle of champagne in its silver bag on the table inside your front door. I wanted to create a little sparkle, and you seem really delighted, as I sit where I’ve wandered with the phone, near the shine at the heart of the dark.

I’m led to a table by myself at a window that looks out on the garden in the ghost of the day. After ordering, I think of the sadness between us. Suddenly, I’m called into the hall to answer the phone, and I hear your voice, clear in the rustle of words from the rooms on both sides, for you call to find out how I am and when I’ll be home, and a quick, fresh sense of the beauty of the late light is like a release after rain.

Back at the table, there’s a glass of white wine, but I sit there to enjoy the expansion of talking with you, a harmony like finding my way when a poem lies hidden in its web of rewriting—only rescued by being spoken out loud to listen for what’s true in the buzz of variations, as your words reshape my feelings among the confusion of glasses and silver from tables nearby— almost a fresh ending it seems, as I take up my glass to taste that other intoxication of wine.

Sitting by a window, I order the wine. Thirty years ago, I’d be lighting up, leaning back in my young body, feeling good. Now smoking’s long gone and youth’s a recovery, not hindered by a glass of chablis.

This is one of those endless afternoons of summer, already 7:30 but plenty of light—like the Regis Roof once in the long blue and white reaches of the sky-bound bar, a ship rising through New York buildings towards the green of the park.

How different to meet at the other end, when it was supposed to be death that would part us, yet how sublime to be the petitioner again, loving you as I have always done, yet lessoned in how gray the dusk is when it comes on alone.

I thought Orion had gone, but you find him high over us, as we walk home in the chill of a freeze, where the thin shell of the sky is filled by stars we don’t know—except for the giant, dancing as if his heart had gotten an eternal frisson of joy— and he’d never suffered a wound during his life as a myth.

When we come in, dog greets us with leaps, which cease as you go out to your car by the back door—time for bed, not here in our house, but in yours, yet as you go you invite me to dinner at the end of the week—two days from now, as nice as the gentle clink of our glasses at the party where no one knows about us, or what we were toasting—and neither do we.

Needing space, I walk out to the back yard, and I have to wonder in the cold night how we will fare. Long ago, looped by love, we breathed an oxygen no one else knew, but at your condo north of town, like a movie star’s tiny castle, I’ll arrive on Friday with flowers— yet I stretch out my arms as if to learn how Orion pulled his tears together into stars.

I arrive at your place and come up the stairs to find you in one of the two big chairs by the windows, where the world of the marsh opens out with tidal pools stretching north, for your home is in a nook on a dry patch of land that delivery guys find too hard to locate and call you from the truck for directions.

So I bring roses myself, and there’s a pleasant time of finding vases, of putting the roses in different ones with you happy—without hesitation. And I hope I can cheer you, because there’s a place we get to—a living memory of when love was the medium between us, and it sometimes returns for a moment, since I never really know where I am until you smile.

Soon I’ll lunch on some left-overs and the Campbell Tomato Soup with a wisp of parmesan cheese that’s sold in 7-Elevens so truckers can use the microwave there, for the 1 minute and 15 second time (as I do) and then get out to their rigs from one stop in the snow—then back on the road, that’s turning white— (“Soup on the Go” says the label).

The French would gasp at the sight, and I can’t lose the memory of a wonderful potato soup I had at the Procope restaurant in Paris, where the place was so old they’d hung out black drapes over the window frames and door when Ben Franklin died— but my heart is with the truckers, and ease, speed, ok hot food, and no pompes funèbres for anyone.

The weather guy describes the snowstorm to come between Atlanta and New York tomorrow, when my daughter is flying to New York. I’m 77 and I can’t text her at work in Atlanta and suggest she drop the flight; she’s 41 and successful—and part of it has been trips in snow to Milwaukee and New York in earlier winters—so 77 must silence himself—must rise up at midnight go out the front door and slip a prayer through the clear stars in a brief exultation of hope to lift her flight safely through the whirling snow, by God’s grace.

She’s off to see clients for whom she executes trades in securities—a threatening job if the stock goes down after she buys it— glorious if it goes up. She studies the market, for she has skeptical guys buying stock in Lululemon athletic gear that she came in this house wearing two months ago, looking like a forester in a shape-tight, dark forest of dreams with white piping on the edges, a frisk around the butt, as she put it. I thought, you’re so near the lips of the latest, a rose in a thorn culture.

Tonight, she has a client to meet by the tall windows of the Four Seasons on Park. The place will be ablaze in light, and the talk will range from business to a good red wine, yet the immediate charm of the night will be enhanced by the varied swirl of the storm. No wonder clients call her from New York to have her do trades,

yet sometimes her world is shaken under the sweet whirl of bucks, for the market moves fast—a mixing of danger, beauty, and hope—like the snow.

I was tossing out a poem and dropped the clip on the carpet. I looked, saw nothing, and got down on my knees to search, because I heard the blip of its landing. No success— until later I reached down, and there it was in a fold of the weave of the carpet.

I felt I’d been given a tiny sign: that my need to shape and polish was going to go on, even if chemo slows me down, for on early mornings darkness and cold offer me the seven stars of the Dipper, a whole design of mystery, aching for words.

My friend goes out in his retirement to help the homeless, who live in the woods around St. Augustine, where some have sleeping bags donated by the local armory, if they are lucky; sometimes they’re in tents. This may be Florida, but winter brings rain and freezing nights, yet Bob is out there giving out sandwiches in a big empty lot.

It is his cheer in describing all this that has a true touch of the holy, while I sit in my chair in my nicely heated home, with English muffins ready to prepare— lots of butter topped off with honey, blurted out of a plastic container.

So, I’m almost guilty because I can’t see myself with my cane, handing out sandwiches in the rain as Bob has done. Yet I can imagine King Lear, in the storm scene, handing out sandwiches to his “loop’d and window’d” poor in his sudden awakening to being able to feel for those he’d never really seen before. How absurd I am, to drag in a recently homeless yet imaginary king, who suddenly cries out for his “naked wretches” yet don’t we all desire to do good?

I admire Bob’s patience, standing there handing out food, especially in what you could call the extra test of rain— in the ragged presence of the poor, people who know what winter is—without apps for the weather— or any way to go home.

Tonight, to give you relief from so much cooking, so you can enjoy being in your own place down the street, I’m going to make my dinner with an omelette, sliding it out of the pan onto the plate with an English muffin, laden with butter and shameless with honey, while I watch the empty night news.

I was on the 57th Street bus, going home, when I realized the magic of words, for Milton quotes from Revelation “and wipe the tears from his eyes” but he adds a “forever” to say, “to wipe the tears forever from his eyes” and changes the value of the line into the music of a curious longing— of release. Did I become a teacher at that enchanted moment? Was I then aimed at Flagler College’s Kenan Hall to preach that words were redemptive and could clear you of the flat and the banal; in fact, could wipe the tears forever from your eyes?

I come out of the hospital in pouring rain with no hat—that’s in the car, which I need to find as I move along as fast as I can, yelling King Lear’s wonderful words on the poor he has never thought about, as he says “Poor naked wretches, whereso’ere you are that bide the pelting of this pitiless storm.” And here I am in a real scene of this world, understanding that “loop’d and window’d raggedness” that brings Lear to a new self as he shambles across the moors.

He adds, “expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,” and in that moment embraces the compassion he needs so badly, while I’m being drenched, finding poetry a wild release out on the spattered macadam of the hospital’s parking lot while looking for my car.

Suddenly, I remember hand carrying my shoes and socks as I walked over flooded Valencia Street to get to class where I taught Lear barefoot, because teaching is a hill to climb without any protection. To say the lines forcefully is to become congruent with every word you remember, as in today’s wonderful wash of storm—shameless in parking lots in truth-telling rain.

I see you squatting in the plastic corner where the eggs have slid away. How pure they are; but you, sophisticated puff of characterless wheat, you are refined so well as to have no use at all— then browned and tinctured in a film of fat until you are a steamboat of disaster in my blood: oh, solid shape that holds like life itself—as true— one message: “Consume me and die.” I do. I do.

From Boston blue with a late snow in a gray pinstriped suit with laced shoes fishwhite I came to be propositioned by a thousand great-bosomed azaleas.

This means the cops came and took names— she was driven away so fast the second time that she doesn’t know if anyone got arrested— “but, Daddy, it isn’t a party if the police don’t come.”

I can’t give her the freedom to die, even as she fills the car with one sentence after another— all of which I believe as I skid in my anger at driving so late to get her outside a bar she’s so young she can’t fool.

slick with wet, as easily waste blood, I find in the swing of my words a fresh envy that it’s her turn to tear up the night under stars that pretend we never burn out.

In the movie, there again she stands a she has stood in reader’s minds for all the years of Ivanhoe we know her champion will come if we know art—he has to come and free her from the Templar’s sneer of death.

But darling life— my daughter at a curl of quilt all comfortable in colored dream of Ivanhoe—how can we know not who comes on horses white or black but who will free her from her mom and dad—what in all of time can take our ghosts out of her blood and leave the child to her own design?

She comes to my body in anger and says, “no love-making for you, if you sleep with prose, or leave me for such an easy encounter–that slut who works any hour.”

She goes back in my darkness alone in a rage to sleep on for weeks outside of reason, and wants none of that sweat brought back to her, or any persuasive excuse.

Poetry’s wild like the blood–blue with passion’s accuracy; just the idea of the clock-hearted whore–her phrase–gets her from bed to lock me out in the world.

Sometimes I see guys with boats hooked to the backs of their cars, but my boat is my car, lapped in traffic, outside of Dothan, zooming north for a little fix in Montgomery by presenting a paper— yet I got myself into this rainy delay, deep in Alabama before a light will let me go left on the great outer circle avoiding downtown.

Suddenly, I find a moment of clarity on this storm-dark morning as nearby lanes move, like gears shifting one after the other. Soon, I’ll blend with a living wafer of motion that whirls around the city in a glory of rain, before a congregation of dingy truck stops, flag-flapping used-car dealerships, and all the worn out motels.

I stop at a diner and look up from my coffee and doughnut, with an odd sense of arrival, for muddy cars with their meshing gears, their oiled lunging and flashes of light yield a mute and dirty communion, desperately rich in the poor world’s glamour, as though we were guests of a greater design than our own, a harmony that’s only a hint of how our true, particular grime masks a substance of grace, as we merge into the sparkling flood, when leaving one lane to turn to another.

You tell me of the deafness of the stars; I say they may not hear, but they do evoke speech, our only response to their glory— brief, synapsing explosions, a pure election of song, of knowing, of need, holy as any universe, for to seek without a template of faith— only its endless invention— is to bridge to the Architect, who lets worlds work themselves out, yet speaks in the pure terms of stars, psalms not beyond our reach— for He troubled the waters and came up with us.

As September here brings on its rains, you start again and wonder what it is you really teach—and how? They’ll give a faithful read, or two, but little more, so you abandon everything and try to walk the great unbalance of Hamlet’s

mesh with murderous events. Your questions seek to share his happiness at speaking well, as if the goal were to enchant deaf time

into that pause where life is faced alone, for the topic’s only one: the ghost, or Grendel—and the poor, brave young.

Susan and I are standing outside on the porch in early October with the sky becoming a shell of light in the first dark.

We compliment each other. It’s easy to praise Susan, and there’s the moon moving towards being full, coming through the palm fronds like a bent coin.

It’s a Florida postcard of the 30s, framed in an even greater nostalgia: the columns of this house, where men in gray walked by after surrendering on the river side of town. How useless to know, but true as the moon, the trees, or the party passing like a leaf.

Does sorrow have to live for us to feel our warmth of fortune? I turn to her (not playing my comic Rhett) and say, you are the realer for the ghosts tonight.

Yesterday, before the big lecture, the idea of afterlife was brushed away by the gifted speaker, leaving us cloud banks of deceased moms and dads, quite exploded, and all our frantic expiations forever undone. I felt like St. Paul knocked off the horse, but not on the ground—somehow uplifted, as if released from the burden of eternity.

But this morning as I stand at the door, I trust my artless prayer, accepting doubt like a ray of faith, for the freckled light through the trees forms a chapel of intensity where I can speak to the moment that is God.

I look deep in the throats of azalea blooms, as dark spots lead down to a magenta depth, and hold my breath—an awe, like one night at school when leaving late after grading exams—there was a moment at the door when the office disappeared with the hum of the lights, when I didn’t care whether God existed and didn’t even need to know, a paradise of tired detachment.

Yet now I find a bloom spelling his name in a speckled Hebrew of genes— for this flower is a last chalice, whose spots are as immediate as the full text that made us beyond all we know, akin to our own tumbling forth of words when only the unprompted seems true.

Suddenly I see a woman on the steep side of a hill, hanging out pale blue sheets. Her home’s surrounded by raw daffodils this February morning; they’ve blotched up through the irregular grass, as I watch her struggle in the wind to hang out her sheets like desperate flags.

North of Gadsden, I think there is no love for us, and the wet outcroppings of rock are clearly weeping something in the browns and blacks of the trees that form the woods Dante was in when he first knew he was lost.

Today, all the way to Huntsville

I’ve understood the word, “lost,” even as I sing it out for the woman, knowing what I’m seeing all the way from Opelika is just what God wants me to see.

Where can I take my vision of daffodils and the blue flags of a hard life?— for the whole world is holding on like a country graveyard where we weep out the truth at last over one terrible stone.

Nearly every one of your poems is gone, due to the exhaustive urges of Byzantine monks, who were promised a high time in paradise for destroying your works.

Later, I stand outside searching the stars for the oldest news, and I think of your lines about legs entwining, saved by quotation, and of one nearly whole poem, where your tongue is dumb and veins on fire, as it is found on the white bed of the Loeb edition, with the scrawny curlicues of the Greek on one side and naked English on the other.

Sappho, body dancing on your bright island, readers still leave libraries to enter the wine shops, soon to be released into the calligraphics of love on the innocent sheets of the body.

At the St. Francis House on a cold day I come in at the back of the lunch line, and stand there with our Christmas ham, not wanting to push my way through. Then, like an interloper, I pass beside a long line of needy, hard-luck guys, almost majestic in their defeat and kingly loneliness, faces lined with regret. They’re in the layered clothing they slept in, and I’m in my cargo shorts, running shoes, and a fresh flannel shirt.

One man at the head steps aside to let me through with a little wince of his hips as if in mockery, and I hand over the scented ham, redolent in its foil, to one of the food servers, who plops it on a stainless steel platter like the head of John the Baptist. Retreating, I find men seated on the edge of the curb who greet me like a good guy, rubbing their hands with the cold.

After my long walk this afternoon with the new freeze coming on, I’ll come in our house, strip off my clothes, and with a paperback of King Lear enter the warm sanity of the bath to read how the world’s greatest bum wanders far on the heath, crying about his people in “loop’d and window’d raggedness,” yet on this fierce night, in vacant lots behind the fish market, some will still find only the cruel little eyes of the stars.

It must be spring in Poland too with green coming back to promise, but I think in shame of the boy arrested on his graduation-party night, and, after being beaten in the police prison, driven to the hospital. The surgeons wept coming out of the operating room his intestines were so mangled.

Pines and maples surround me where I write, and as I walk out the undersides of leaves take on the sleepy shades of clouds, yet the sun makes each one an individual.

You want phrases like, “May God cry out over Poland,” you want them bad, but it is more true to look at the leaves to stretch out with them for the line of life is close to their veins.

I mourn Poland, the light, and what the light must see; we are not up to being alone.

I’m in my office at school and he’s sitting near the window quietly talking about writing, so full of a benign giving, yet soon he’s on his way, ever the prince of farewells, who goes out of the glass door of the department and turns to wave—a bird-wing wave, a salute, and he’s gone.

When I wake, I feel I won’t see him again, for this exchange between night and day suggests I must take my own route, and ends with that adios to the soul.

I’ve just come back from the empty slip where this sailboat was docked— a sad moment of standing there— no sunny green swells in the water but dark, cold looking, and deep as death for one who is coming off chemo to go it alone until the next stop before Hospice; I’m not depressed, for I get out of bed early each morning with the hope of a poem to outdo my others—a lifetime of tries with a few successes, but no naked genius like me now, suddenly swimming in the cold water: white thin limbs thrashing around, calling out “God of this world surely this is confession enough.”

If I were depressed, I would not leap out of bed or into this black water, yet I’d be no more slow to get my coffee and search the world for the boat of my hope, the empty pockets of my dreams.

College faculty in the fall of 1972. During his 33 years at the College, he taught courses in Shakespeare, Milton, Chaucer, and Renaissance Literature, as well as the Survey of English Literature and Creative Writing.

A native New Yorker, Dr. Dillon earned his Bachelor of Arts degree at City College of New York and his Master of Arts and Ph.D. degrees from New York University. Prior to coming to Flagler, Dr. Dillon taught at the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn and Northeastern University in Boston.

Twice recognized by the Student Government Association as an Outstanding Teacher, Dr. Dillon was known for his creative and dramatic interpretations of literary works that inspired in his students a life-long love of literature.

In addition to his keen interest in Shakespeare and other Renaissance authors, Dr. Dillon had a love for poetry and devoted much of his personal time to writing. Over 200 of his poems have been published in literary journals. Dr. Dillon also published critical essays and book reviews in professional publications.

Dr. Andrew Dillon joined the Flagler