3 minute read

A Brief History of Celebrating Independence Day

Among all the holidays, one stands out as preeminently American, reflecting the patriotism and national pride of its citizens. Independence Day, or the Fourth of July, is observed in every state in the nation as our distinctive national holiday, commemorating the date of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, the document that declared our country free from British Rule.

John Adams wrote a letter to his wife at the time of the adoption, sharing his feelings on the significance of the event. “I am apt to believe,” he wrote, “that this day will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forevermore.”

Though Adams was talking about July 2, the day the colonies resolved to separate from Britain, he accurately predicted public sentiment.

The first Independence Day celebration took place the following year, in 1777. The largest celebration that year took place in Philadelphia, and included an official dinner attended by the Continental Congress, a 13-gun salute, bell ringing, orations, and fireworks displays. The custom of commemorating American independence spread to other towns, both large and small, where the day was marked with processions, oratory, picnics, contests, games, military displays, decorations, and fireworks.

By the end of the War of 1812, observations throughout the nation became even more common. On June 28, 1870, Independence Day was established as an official federal holiday in the District of Columbia, and extended nationwide in 1885, codifying the celebrations practiced in many states since the late eighteenth century. The Fourth of July became a paid holiday for federal employees in 1941.

Independence Day celebration customs have changed little over the years, with the traditions of patriotic addresses, musical concerts, games, picnics, parades, and fireworks displays still popular. Nineteenth-century magazines, newspapers, and household manuals offered many suggestions for decorations, songs, and menus for the occasion, but also began to document the dangers associated with the festivities.

By the second half of the nineteenth century, concern had grown over the number of injuries and deaths associated with Independence Day celebrations, due to the unregulated and unsupervised use of fireworks, guns, and fires. American poet and author Julia Ward Howe, best known for writing the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” was invited to present her ideas on the proper celebration of the holiday in the 1912 publication Independence Day: Its Celebration, Spirit, and Significance as Related in Prose and Verse. In reaction to previous raucous and violent demonstrations, Howe relayed that during her lifetime, the “endless crackling of torpedoes, the explosion of firecrackers and the booming of cannon, made the day one of joyous confusion and fatigue … devoted to boyish pleasure and mischief.” “Going out of town to avoid the Fourth” became a common activity among city dwellers to escape the noise, crowds, and risk of injury.

Deaths and injuries caused by pistols (both real and toy), metal caps, fires, firecrackers, and exploding powders finally became such a problem that by the late 1890s, campaigns were started for “the safe and sane celebration of the Fourth of July.” Such campaigns lead to ordinances regulating fireworks and explosives across the United States. Newspaper accounts recounted the reduction in the number of Fourth of July fatalities over the previous few years. According to The New York Times, July 6, 1912, “The best kind of patriotism is controlled by intelligence, and there is surely no intelligent person left now who believes in the ‘good, old-fashioned Fourth of July’ with its long death roll and list of losses and insurance.”

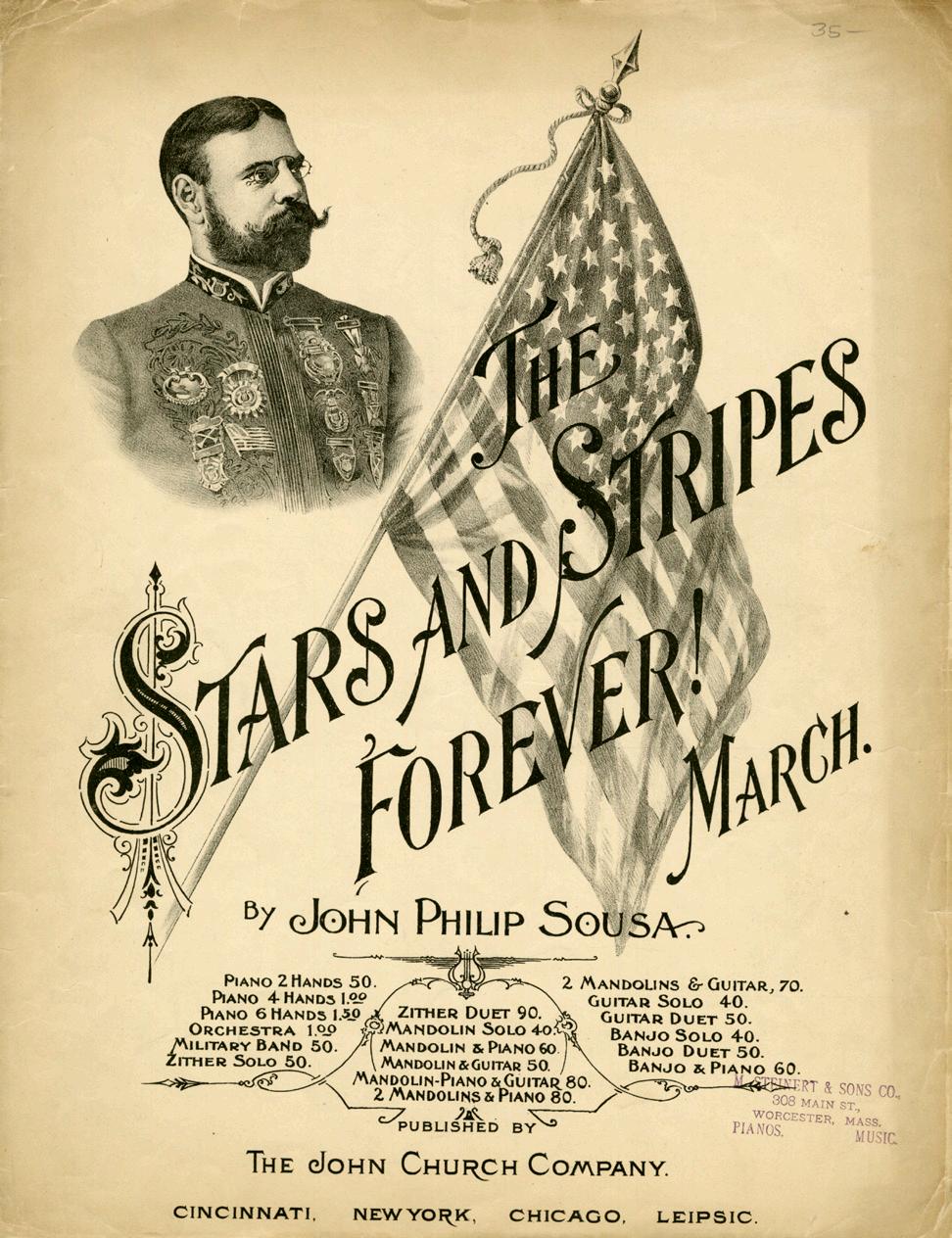

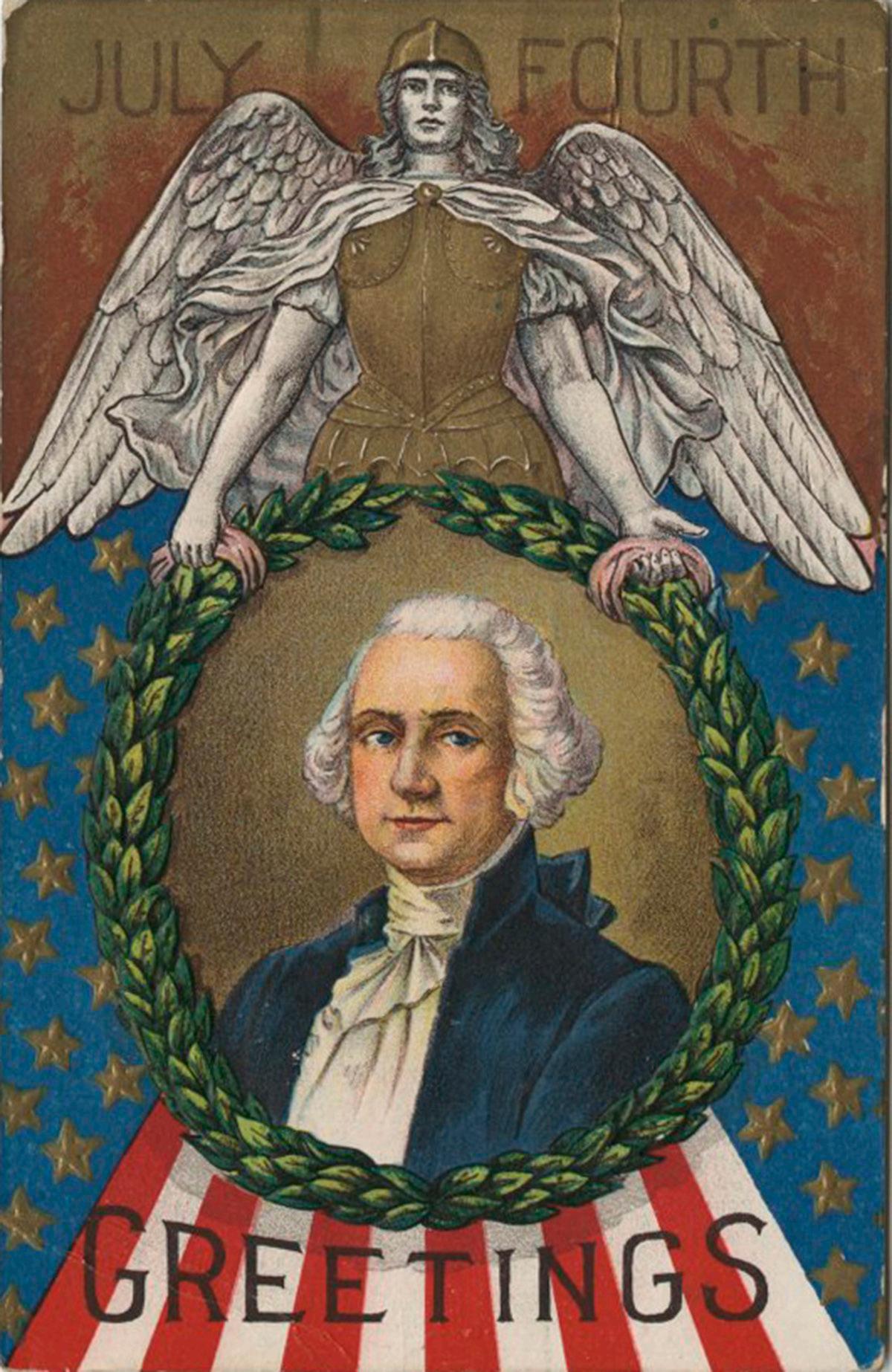

The Flagler Museum Archives houses many archival items that testify to the significance of the holiday in America and the patriotism of the period, including sheet music, postcards, menus, and rare books. Most of these objects feature popular motifs such as George Washington, Uncle Sam, the American Eagle, the flag, and fireworks, all of which are evoked today to symbolize American patriotism and pride.

The tradition of celebrating the Fourth of July in Gilded Age fashion continues each year at the Flagler Museum.