The Journal of the National Art Education Association September 2010 Volume 63, No. 5 $9.00

Special Double Issue

“I am moved by the proposition that education is a vehicle of social transformation.”

EDITOR: Flávia Bastos EDITORIAL ASSISTANT: Kelli Aquila Instructional Resources Coordinator: Rina Kundu EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD: Cynthia Bickley-Green, Melanie Buffington, Kelly Campbell-Busby, Sheng Kuan Chung, Nicole Crane, Melanie Davenport, Read Diket, Rick Garner, Mark Graham, Jay Hanes, Suzan Harris, Jay Heuman, Olga Hubard, Karen Hutzel, Themina Kader, Sharon Johnson, Lilly Lu, Marjorie Manifold, Anne Marquette, Elizabeth Reese, Priscilla Roggenkamp, Ryan Shin, Cathy Smilan, Kryssi Staikidis, Michelle Tillander, and Gina Wenger. NAEA BOARD: Barry Shauck, Bonnie Rushlow, F. Robert Sabol, Deborah Barten, Mark Coates, Kim Huyler Defibaugh, Patricia Franklin, Kathryn Hillyer, Mary Miller, Bob Reeker, Diane Scully, Lesley Wellman, John Howell White, and Deborah Reeve. NAEA Design and Production: Lynn Ezell NAEA Staff Editor: Clare Grosgebauer Art Education is the official journal of The National Art Education Association. Manuscripts are welcome at all times and on any aspect of art education. Please send one double-spaced copy and a CD with digital files, prepared in accordance with the 6th edition Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association to Dr. Christine Ballengee-Morris, Editor, Art Education Journal, Department of Art Education, 128 North Oval Mall, Columbus, OH 43210 To facilitate the process of anonymous review, the author’s name, title, affiliation, mailing address, and phone number should be on a separate sheet. Retain a copy of anything submitted. For guidelines, see Art Education under ‘Writing for NAEA’ at www.arteducators.org. Authors are encouraged to submit photographs with their manuscripts. Art Education is indexed in the Education Index, and available on microfilm from University Microfilms, Inc., 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. For quantity reprints of past articles, please e-mail lezell@arteducators.org for order forms. © National Art Education Association 2010. Allow up to 8 weeks to process new member and subscription publications. Art Education (ISSN 0004-3125) is published bimonthly: January, March, May, July, September, and November by The National Art Education Association, 1806 Robert Fulton Drive, Suite 300, Reston, VA 20191. Telephone 703-860-8000; fax 703-860-2960 Website: www.arteducators.org Membership dues include $25.00 for a member’s subscription to Art Education. Non-member subscription rates are: Domestic $50.00 per year; Canadian and Foreign $75.00 per year. Call for single copy prices. Periodicals postage is paid at Herndon, VA, and at additional mailing offices. Printed in the USA. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Art Education, National Art Education Association, 1806 Robert Fulton Drive, Suite 300, Reston, VA 20191.

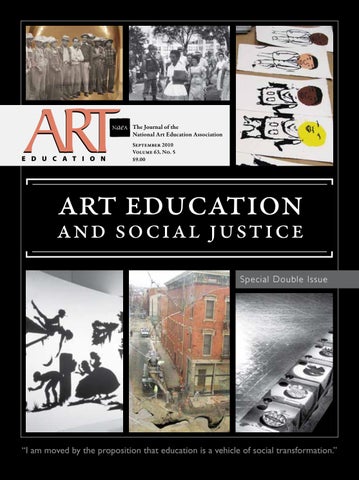

Cover (details from images, clockwise from top): Image from “Y Se Repite,” p. 57; image from “Art in Social Studies Assessments,” p. 31; image from “An Inevitable Question.” p. 6; image from “An Invitation to Social Change,” p. 36; image from New Voices program, Fall of 2009, high school program produced by Prairie, Inc. for SCPA students in Cincinatti, Ohio; image from “Art in Social Studies Assessments,” p. 33. Quote from Editorial, p. 3.

The Journal of the National Art Education Association

contents

September 2010 [Volume 63, No. 5]

Editorial

What Does Social Justice Art Education Look Like? [ Flรกvia Bastos ]

An Inevitable Question:

Exploring the Defining Features of Social Justice Art Education [ Marit Dewhurst N ]

Structuring Democratic Places of Learning: The Gulf Island Film and Television School [ Juan Carlos Castro N and Kit Grauer ]

The Challenge of New Colorblind Racism in Art Education [ Dipti Desai ]

Art in Social Studies Assessments:

An Untapped Resource for Social Justice Education [ Susan Zwirn and Andrea Libresco N ]

An Invitation to Social Change:

Fifteen Principles for Teaching Art [ Carrie Nordlund N , Peg Speirs N , and Marilyn Stewart N

Instructional Resources | Exploring Racism through Photography [ Cass Fey, Ryan Shin, Shana Cinquemani N , and Catherine Marino N ]

Your Art is Gay and Retarded:

Eliminating Discriminating Speech in the Secondary Arts Education Classroom [ Brian Payne N ]

2

6

14

22

30

36

44

52

Y Se Repite

56

Folk Art in the Urban Artroom

62

[ Adriana Katzew N ]

[ Donalyn Heise ]

A Cross-Cultural Collaboration:

Using Visual Culture for the Creation of a Socially Relevant Mural in Mexico [ Kathy Hubbard ]

Fundreds in Arkansas: An Interdisciplinary Collaboration [ Angela M. La Porte ]

The 2010 Lowenfeld Lecture | Creativity and Art Education: A Personal Journey in Four Acts [ Enid Zimmerman ]

68

78

84

figure 1 Photo by Eleanor Batista-Malat, grade 7, October 2009.

Editorial

what does social justice art education look like? Education for social justice is education for a society where the rights and privileges of democracy are available to all. Art education for social justice places art as a means through which these goals are achieved (Garber, 2004, p. 16). Social justice involves a negotiated vision, which can be surprising at times. The photograph above is from a community art program called Kid’s View: On Assignment, sponsored by Prairie, Inc. (http://www.cincinnatikidsview.com/), a Cincinnati art gallery with a strong mission of community engagement and social justice. In this program, 10 local middle-school age children participated in an after school photography class that introduced

them to four community agencies in the surrounding Northside neighborhood. One of these agencies, Visionaries and Voices (http://www.visionariesandvoices.com/content/vv-home/) provides art studio space, activities, and exhibitions for adults with developmental disabilities. Kid’s View students learned about the work of Visionaries and Voices’ artists, especially Nikki Martin, a fashion designer who created the garments modeled by other Visionary and Voices artists and staff in a fashion show. At face value, a traditional white-clad bride in the runway strikes as conventional (Figure 1). It is tempting to interpret any fashion show as a celebration of consumer culture, and the bridal figure as the embodiment of glamour, women’s wedding fantasies, and mainstream representations of marriage as a heterosexual union. However, under the surface, we find nuance. This fashion show was created and carried out by people often excluded from the creative side of the fashion industry, and, therefore, it

became empowering. Furthermore, the event took place just before the local election and had the goal of creating awareness about a levy issue supporting the city’s developmental disabilities services, which was ultimately sanctioned. The photograph demonstrates that Kid’s View students learned about photography, but more importantly, they also learned about the exciting affinity between art and activism, the importance of getting involved, and the possibility of making a difference. Transformative Education | I am moved by the proposition that education is a vehicle of social transformation. I am first generation college-educated, of a mixed-race background, non-American from a developing country, not a native speaker of English. I taught kids who did not have shoes, let alone textbooks, and kids who lived in gated communities and came to school in chauffeured import cars. Through my personal and teaching experiences with elementary grades in both private and public schools in Brazil, as well as my current academic work in the United States, I contemplated the breath of the social gap, and witnessed the transformative power of learning. This transformative work is personal, it is based on constant and evolving reflection about our own instances of oppression and privilege, as much as that of our students.

–Flávia M.C. Bastos, Editor

References Freire, P. (2006). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum. Gablik, S. (1993). The re-enchantment of art. New York: Thames and Hudson. Garber, E. (2004). Social justice and art education. Visual Art Research, 30(2) 4-22. Praire Gallery. Retrieved June 2, 2010 from http://www.cincinnatikidsview. com/onassignmentgallery.html Visionaries and Voices. Retrieved June 2, 2010 from http://www. visionariesandvoices.com/content/vv-home

Flávia M. C. Bastos is an Associate Professor of Art Education and Director of Graduate Studies, College of Design, Art, Architecture and Planning, University of Cincinnati. E-mail: flavia.bastos@uc.edu

Ar t E du cati on [ S eptemb er 20 10 ]

I am extremely grateful by the support of our organization in making this issue possible and I expect it will make an impression on you. It makes a powerful statement about or field’s engagement in relevant social justice work. It announces connections between creativity, art teaching, and transformation. It indicates that social justice is an important, perhaps essential, dimension of our profession. To my question of “what social justice art education looks like?” I offer this carefully crafted issue of the journal as a partial answer. Another fundamental aspect of doing social justice art education work is predicated on our ability to create and support a professional community who cares about these issues. Social justice art education can be surprising, personal, and multifaceted. Echoing the powerful shift from objects to relationships evidenced in postmodern art (Gablik, 1993), it invites a new type of professional engagement. This compelling Art Education issue enables us to contemplate facets of our work for change and inspires us to keep going.

3

Social Justice Issue | My enthusiasm for theme of past convention dovetails with a large contingent of the organization’s membership, as evidenced in the many quotes from conference attendees. An impressive line-up of contributors, working in the United States, Canada and Mexico, discusses several dimensions of social justice, including issues of race, social class, art world’s hierarchies, interdisciplinary connections, and creativity. They collaborate with activist artists, present their own artwork, and transform learning spaces around them, such as their own classrooms, museums, community centers, or the streets.

This special social justice issue expects to (1) provide written documentation of the convention’s theme by serving a postfacto proceedings of selected presentations and panels, (2) carry the ideas and concerns shaping the convention to the entirety of our membership, especially those unable to attend the conference, and (3) create opportunities for continued reflection about the conference’s theme.

23

This special issue of Art Education is shaped by a vision of the journal as a transformative educational vehicle that can further the education of our membership not to accomplish conformity, but to engage in “the practice of freedom, the means by which men and women deal critically and creatively with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world” (Freire, 2006, p. 53). This issue celebrates the unique role and potential of art in promoting a kind of critical awareness that generates understanding, discourse, and actions aimed at change. Freire affirms unequivocally that only humans “are able to achieve the complex operation of simultaneously transforming the world by their action and grasping and expressing the world’s reality in their creative language” (p. 68). It follows from this proposition that art education’s humanistic mission can better be fulfilled in the promotion of change, and the quest for social justice.

The special design pays homage to the distinguished 13 contributions that comprise this issue. Capitalizing on the graphic design expertise available at my home institution, and the background of my Editorial Assistant Kelli Aquila (see guest designer statement), designing this special issue also became an educational project as it was integrated into Ms. Aquila’s capstone experience in the Art Education Master’s Program.

comments from 2010 naea national convention attendees: [This conference gave me voice!] [The art teacher can, and perhaps should, assign content-driven problems (social, or otherwise) for the student to explore. However, the art teacher should not, overtly, influence the students to take up his or her pet social, political, or religious agendas.] [I thought the theme was almost tired, but it was not terrible.] [Loved the convention theme. Such an important and relevant topic!] [I would like to see some effort to bridge the gap between theory and practice for the practicing art teacher. When is the last time you had a primary or secondary art teacher speak at a general or super session?] [Bravo to the NAEA board, Division Directors, Regional Presidents, Maryland Host Committee, and staff for creating and facilitating the important, groundbreaking 50th Annual Convention Theme, Art Education and Social Justice!] [It is important that the topics apply to all students from the privileged to the at-risk.] [This was one of the best NAEA conventions I have attended. Perhaps it was the nature of the theme that lead to deep and intriguing connections for the arts.] [Social Justice theme was not appropriate for all levels. I did not find the workshops to be practical. There was very little that I was able to use in the classroom.] [The theme, Social Justice, was timely and well-explored. I wonder how it will make a difference to the way in which art is taught in our country?] [I thought convention was completely relevant to my teaching practice as a community artist and teacher.] [As an elementary art teacher I can hear someone say, ”social justice for elementary?” ‘You better believe it.’]

figures From New Voices program, Fall of 2009, high school program produced by Prairie, Inc. for SCPA students in Cincinatti, Ohio.

From the guest designer: I have described myself as many things: daughter, friend, student, artist, graphic designer, teacher. As editorial assistant of Art Education, I have been pushed to explore the ways in which these many roles intersect and overlap, framing a unique perspective. I learned that art, design, and education are not separate entities, but interdependent fields that inform and encourage one another.

Kelli M. Aquila is a Master of Art Education student at the University of Cincinnati and is excited to start teaching this fall at Hilliard Bradley High School in Hilliard, Ohio.

References Ballengee-Morris, C., & Stuhr, P. L. (2001). Multicultural art and visual cultural education in a changing world [Electronic version]. Art Education, 54(4), 6-13. Cranmer, J., & Zappaterra, Y. (2003). Conscientious objectives: Designing for an ethical message (p. 75). Mies, Switzerland: RotoVision SA. Samara, T. (2005). Publication design workbook: A real-world design guide (pp. 13-14). Beverly, MA: Rockport Publishers, Inc.

Ar t E du cati on [ S eptemb er 20 10 ]

As Guest Designer of this special issue, I was challenged to help our readership access, engage with, and find meaning in the ideas presented by our authors. Because the written word is meaningless if no one takes the time to read it, my goal was to create a professional, engaging layout to catch the readers’ eyes, pulling them into the work (Cranmer & Zappaterra, 2003).

– Kelli M. Aquila, Editorial Assistant & Guest Designer

5

A more democratic approach, whereby the disenfranchised are also given a voice in the art and visual culture education process and the disenfranchised, as well as the franchised, are sensitized to taken-for-granted assumptions implicit in personal, national, and global culture.

Thank you, NAEA board and staff, for supporting this special issue, especially Publications Manager Lynn Ezell for giving me this opportunity; thank you to Flavia Bástos for your constant guidance and encouragement as my professor, mentor, boss, and friend; and thank you to our readers for bearing with me—I am honored to have been a part of this issue and look forward to your response.

4

According to Timothy Samara (2005), the primary function of design is to give form to an idea or subject matter in a way that is relevant and accessible to a particular audience. The vast array of issues, ideas, and perspectives encompassing the theme of social justice make it an intimidating subject matter. BallengeeMorris and Stuhr (2001), provide a holistic look at “the dynamic complexity of factors that affect all human interaction: physical and mental ability, class, gender, age, politics, religion, geography, and ethnicity/race” (p. 10), and propose for art education,

To increase accessibility and value to our audience, I chose to: break the articles down from large blocks into smaller more digestible chunks, mimic the natural motion of reading from left to right, use large images at the top of many pages to draw readers in while maintaining the flow of reading, and form strong horizontal bands that create movement between spreads. The combination of typefaces Adobe Garamond and Gill Sans signifies the field’s ability to incorporate art’s historical past into meaningful discourse regarding contemporary ideas. This final design represents a true intersection of my roles as artist, designer, and art educator.

figure 1 This series of prints aims to draw attention to racial stereotypes in our society.

an inevitable question: Explor ing the Defining Features of Social Justice Ar t Education

By: Marit Dewhurst

“What do you really mean by social justice art education?” It is an inevitable question. In fact, I would be shocked if no one tentatively raised his or her

workshops in museums or graduatelevel education classes to earnestly ask, by social justice art education?” I am not surprised because this question constantly causes confusion among not only the students, but also the educators, researchers, and artists working at the intersection of art, education, and social justice. The labels for this work come in many shapes, among them, activist art (Felshin, 1995), community-based arts (Knight & Schwarzman, 2005), new public art (Lacy, 1995), art for social change (O’Brien & Little, 1990), and community cultural development (Adams & Goldbard, 2001). Despite these various names, this work often shares a commitment to create art that draws attention to, mobilizes action towards, or attempts to intervene in systems of inequality or injustice. And yet, in a field with growing numbers of social justice arts organizations

And so I am not startled each time a student hesitantly asks, with a hint of frustration or even exasperation, “What do you really mean by social justice art education?” In responding to this inevitable question, those of us engaged in this work must parse out exactly what it means to do social justice art education. If we fail to rise to this challenge we risk losing the clarity required to advocate for our work, to train future educators, and perhaps most importantly, to separate out art practices that truly impact injustice and those that may

Ar t E du cati on [ S eptemb er 20 10 ]

“Sorry, but just what do you really mean

7

education professional development

6

hand in any of my art and social justice

and the accompanying conferences, special journal issues, and edited books, the very definition of what is meant by social justice art education remains elusive. Some variation in nomenclature can be attributed to the multiple disciplinary lenses—from art history and anthropology to community development and public policy—that have been used to analyze this work. However, hidden in this tenuous terminology are competing visions about the very nature of social justice art education. Such differences appear to hinge on three main debates: (1) how strategic the artistic and activist decisions are in relation to their potential to effectively change policy; (2) what constitutes activism or social change; and (3) if emphasis is placed on the process or the product of artmaking. These big, often philosophical debates require us to unpack the purposes, expectations, and perspectives that compel us to mix art and social justice work.

figure 2 Paulina’s “Homeless in New York “ postcards sought to change audience perspectives about the prevalence of poverty.

If critical pedagogy is about learning to critically examine the world around us—to pull apart the structural factors that lead to injustice—then why stop at the obvious examples of inequality?

inadvertently perpetuate inequality under the name of good intentions. If everything can be contained under the term social justice art education, then we lose the opportunity to further research and develop the unique possibilities of this particular approach to learning in the arts.

critical pedagogy, a pedagogy of its own emerged. While this pedagogy of activist art1 is by no means conclusive, it raises several distinctions that hone our understanding of what really is social justice art education.

Observing, interviewing, and working alongside young people as they create works of art that critique, contest, and strive to affect conditions of injustice, I have witnessed the ways in which social justice artmaking begins to take on a certain shape. To explore that shape, I recently conducted a qualitative study that examined the educational processes that occur when young people create works of art to impact injustice (Dewhurst, 2009). Through interviews and observations of 14 teenagers participating in a free after-school activist art class, I investigated how they experienced and described the act of making a work of art to impact injustice. In analyzing the ways in which these young people approached their own social justice-driven artmaking, I noticed three main pedagogical activities— connecting, questioning, and translating—that comprised the practice of making a work of activist art. As I integrated these observations and experiences with the theoretical literature on

A Particular Practice Social justice education in the arts is a practice—an evolving, iterative process. As critical pedagogy scholars write, social justice education is a way of teaching that seeks liberation for all people (Horton, Kohl, & Kohl, 1998; Freire, 1970; hooks, 1994). As such, the means—as much as the end product—are integral to make a work of art “activist” or “social justice” in nature. While people often assume that social justice art education must be based on controversial or overtly political issues (i.e. race, violence, discrimination, etc.), this is not always the case. Rather, as long as the process of making art offers participants a way to construct knowledge, critically analyze an idea, and take action in the world, then they are engaged in a practice of social justice artmaking.

9 9 Christian’s experience offers a glimpse into the key pedagogical activities of a social justice art practice. A closer look at the processes and examples that emerged from the young artists participating in my research suggests that this practice has a particular shape. The following dimensions constitute a pedagogy of activist artmaking that sheds light on the educational significance of creating art for social justice. Connecting. Pulling from the language of social justice education, activist artists “start where they are.” To identify these connections, activist artists engage in critical reflection and attentive exploration of the ways injustice plays out in the world and in relation to the artist’s own life. These acts of naming and articulating are ways of learning about the nature of injustice. As 16-year-old Paulina described, seeing the issue of homelessness take on a life within her own everyday experiences grounded her even more within the issue: “And everywhere I went I actually became noticing homeless people [sic]…. starting to do the project it opened my eyes again and I was able to see them.” Questioning. Activist artists embark on a quest for a deeper understanding of the issues of injustice about which they will create art. These investigative and analytic questions lead to

Ar t E du cati on [ S eptemb er 20 10 ]

Christian,2 a young artist in a social justice photography class I taught, was adamantly committed to fashion photography. While other students gravitated to the topics I had anticipated—school reform, gender inequality, domestic violence—Christian’s choice of fashion seemed a far cry from the activist topics I had expected. Frustrated, I sat down as he arranged his photos in lines. I asked him questions about the choices he had made, about his love of fashion, about why it felt compelling. And then, why did it matter? To whom did it matter? What purpose did it fulfill? And as I asked these questions—drawing out some of the cultural, social, psychological, and economic factors embedded in the idea of fashion—our conversation grew more animated. We soon found ourselves questioning some of the murky cultural and economic significance of fashion. Suddenly, Christian was connecting fashion to a social pressure to conform to different class standards. And suddenly, I began to understand that perhaps the “social justice-ness” is not tied to specific subject matter. If critical pedagogy is about learning to critically examine the world around us—to pull apart the structural factors that lead to injustice—then why stop at the obvious examples of inequality? Why not engage in such a critical examination of technology, science, or, for that matter, fashion?

figure 3 Estela’s final project balanced activist intentions and aesthetic aims.

an unfolding and critical inquiry into the multiple social, cultural, political, and economic factors that contribute to their selected issue. In conducting research on their issue, artists experience varying levels of an increased critical consciousness about the meaning of their issue within the world. Through both posing and pursuing questions, activist artists are simultaneously learning and teaching about social issues in ways evocative of critical pedagogy’s collaborative problem-posing education (Freire, 1970). Seventeen-year-old Alejandra described her critical realization of the number of unrealistic images of women that exist in the magazines she often reads after examining them in light of her project on body image: “So just learning the statistics… you don’t realize, like how many bad images there are in magazines, so… it really helped me to look at, you know, magazines differently.” Translating. Activist art is created with an express intention to challenge and change conditions of inequality or injustice. This requires artists to move beyond surface illustrations of injustice to make tactical decisions about how best to affect structures of oppression—not just the symptoms. Art

made for social justice is not simply a meandering inquiry into the play of light or color across a page, but an inquiry motivated by a specific, purposeful desire to impact structures of injustice. In the act of translating, activist artists negotiate the concurrent goals of creating an aesthetic object and achieving their intended activist aims. Translating requires activist artists to critically reflect on the purposes of their artwork and to match those with appropriate artistic tools, materials, and techniques. Watching students negotiate the balance between intended impacts and aesthetic aims reveals the unique challenges of making art for social justice. Estela, a teen participant in a mixed media activist art class, was nearly finished with her final sculpture when she ran up against a problem. Estela began her project with a vision to use a singed American flag. “But,” she described, “I thought about it and I felt that, that it was too manufactured.” Estela worried that the inclusion of the American flag would not only be overpowering, but it would also hide the intricate collage of newspaper clippings she had carefully constructed. To cover these clippings would diminish her intention

Student-Driven Projects | Educators striving to encourage learners to direct their own projects should leave room for learners to identify and define their own artmaking. Prompts and assignments should offer multiple opportunities for interpretation and experimentation so students have control over the direction of the project. There should be many ways in which a student can make decisions to create their own version of the assignment. Students should be encouraged to articulate their intentions for their artwork and to share those with others. To this end, educators should allow learners to select their own topics for exploration and respond with activities and lessons that move students into a deeper analysis of their topics. Educators must trust that the processes of connecting, questioning, and translating will allow students to create final works of art that successfully achieve both their activist and aesthetic aims.

Despite the warning that social justice art education must be responsive to the specific people and place in which it takes place, the question remains: “How does one really do social justice art education?” For educators interested in the intersection of artmaking and social justice education, Art made for social justice the challenge of teaching in a is not simply a meandering way that encourages learners to identify, critique, and take inquiry into the play of light action to dismantle unjust or color across a page, but structures of power can be overwhelming and filled an inquiry motivated by a with uncertainty. However, the key pedagogical features specific, purposeful desire to articulated above suggest a impact structures of injustice. series of strategies for initiating social justice art education projects. Collaborative, Reciprocal, and Contextual Planning | Before proceeding with any set of practical tools, it is imperative that we understand that social justice art education involves teachers and learners building understanding and action together. Therefore, this approach to art education requires a fundamental shift in the relationship between students and teachers. Such co-constructed learning, what Lissa Soep (2006) refers to as “collegial pedagogy” is core to critical pedagogy and empowers all participants to act

Relevant Reflection | To encourage the process of connecting, educators should develop lesson plans and activities that encourage learners to reflect on their own identities, experiences, and interests to help them identify project topics that are meaningful and rooted in students’ own lives. They can then help students locate topic ideas within students’ own daily interactions, environments, and relationships by motivating them to attend to the ways in which their topic appears in their lives.

Ar t E du cati on [ S eptemb er 20 10 ]

Doing Social Justice Art Education

11

as agents, not subjects of their own practice. A commitment to collaboration and reciprocity allows participants to both direct the development of their intended artistic and social justice impacts towards their audience while also experiencing some of those impacts (increased awareness, critical consciousness) themselves. This shift in attitude has dramatic implications on curriculum planning. There is no formulaic script, no universal step-by-step curriculum. What works with one group of participants, in one community, in one particular institution may or may not work with another group. The practice must be iterative and evolving based on the people and contexts—in school, out-of-school, in a particular community, etc.—at play. Given this challenge, educators interested in planning for social justice art education may find the following practical characteristics useful in scaffolding their teaching.

11 10

to educate viewers about current civic rights violations. And yet, without the flag, the connection to American policies faded, weakening her desired impact to have viewers reflect on their rights as U.S. citizens. To add the vibrantly colored flag over the somber blacks and grays of her piece could impede the aesthetic success; to leave it out might render her intended impact invisible. At last, Estela reached a solution: she thinned the red and blue paint, resulting in a translucent veil of color over her collage—enough to convey the idea of a flag without losing the aesthetic appeal of the subdued colors or the critical details in the collaged clippings. Holding both aims throughout her process, Estela thoughtfully negotiated the balancing act between the drive for an aesthetically engaging work of art and one that would still result in her intended impact.

Critical Questions | Building on the web of connections laid out through the process of connecting, educators can shift to questioning as a tool to prompt learners to delve into a study of their topics. This process enables learners to gather the information and multiple perspectives necessary to create works of art that strategically aim to impact social justice. Through activities ranging from one-on-one questioning and collaborative informationgathering projects, to more conventional research techniques such as interviewing, literature analyses, and basic statistics, educators can support the unfolding inquiry that will result in richer understandings of the various structural (i.e. cultural, political, economic, etc.) factors contributing to injustice. Educators should encourage both investigative (What’s happening?) and analytic (Why is it happening?) questions that help students identify the possible tactics and tools to effect change. A Tactical Balance | Once students narrow in on the specific strategies they will use to create their works of art, they begin the process of translating their ideas into objects or actions that will affect injustice. In this phase, students should be encouraged to balance both their activist intentions and their aesthetic aims—sacrificing neither one for the other. This process requires both individual and group critiques that facilitate discussion about the possible reactions of the audience to help learners revise their work. Ideally, students would be encouraged to explore a range of media to select what materials and methods are most appropriate to alter the systems of injustice they identify. Public Audience | Art that is created to challenge or change injustices must be allowed to leave the confines of the room in which it was made in order to reach the intended impacts of the artist. While this step can open up students and educators to criticism and censorship, to lock it up is to prevent the work from actually influencing inequality and therefore really becoming activist art.

Conclusion In classrooms, community centers, museums, and alternative learning sites across the country, large numbers of young people are creating works of art—from murals and plays, to photographs and poetry—that question, challenge, and at times, impact existing conditions of inequality and injustice. As educators, researchers, and artists interested in understanding and supporting this work, we must continue to try to define the work we do, even if our answers are not quite complete. If the growing number of youth arts organizations and schools claiming to offer social justice art education is any indication, this field will continue to expand. With this expansion will come more complicated questions about the nature of social justice art education. Questions regarding an educator’s insider or outsider status within a community, or who is responsible when a project “fails” or whether or not the young people creating work should be paid may soon become the next critical questions we ask each other. As intriguing and necessary as these next questions are, we are ill-equipped to debate them until we have come to a stronger understanding of what we actually mean when we call something social justice art education. Only then, when we can answer the inevitable question about the very definition of social justice art education will we be able to truly advance the powerful possibilities of this work.

Endnotes 1

Throughout this work, while I usually refer to social justice artmaking I also occasionally employ the term activist art synonymously. I use the term social justice art not only because The National Art Education Association framed the 2010 Annual Convention and this issue of Art Education around this term, but also because many youth arts organizations employ the term in their program literature. I also use activist art, as it similarly captures the artist’s explicit desire to bend dominant systems of power towards justice and equality.

2

Names of youth participants have been changed for confidentiality.

Ar t E du cati on [ S eptemb er 20 10 ]

Marit Dewhurst is Director of Art Education and Visiting Assistant Professor at City College of New York, New York City. E-mail: marit_dewhurst@mail. harvard.edu

Knight, K., Schwarzman, M. & many others. (2005). Beginner’s guide to community-based arts: Ten graphic stories about artists, educators, and activists across the U.S. Oakland, CA: newvillagepress. Lacy, S. (1995). Mapping the terrain: New genre public art. Seattle, WA: Bay Press. McLaren, P. (2003). Critical pedagogy: A look at the major concepts. In A. Darder, M. Baltodano, & R. D. Torres (Ed.), The Critical Pedagogy Reader. New York: RoutledgeFalmer. O’Brien, M., & Little, C. (1990). Reimaging America: The arts of social change. Philadelphia, PA: New Society Publishers. Soep, E. (2006). Youth mediate democracy. National Civic Review, 95(1), 34-40. Shor, I. (1992). Empowering education: Critical teaching for social change. Chicago, IL:The University of Chicago Press.

13

figure 4 A student in an activist art class adds the finishing touches to his project.

13 12

References Adams, D., & Goldbard, A. (2001). Creative community: The art of cultural development. New York: Rockefeller Foundation Creativity & Culture Division. Darder, A. (2001). Reinventing Paulo Freire: A pedagogy of love. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Dewhurst, M. (2009). A pedagogy of activist art: Exploring the educational significance of creating art for social justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Graduate School of Education. Felshin, N. (Ed.) (1995). But is it art?: The spirit of art as activism. Seattle, WA: Bay Press. Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder. hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York: Routledge. Horton, M., Kohl, J., & Kohl, H. R. (1998). The long haul: An autobiography. New York: Teachers College Press.

structuring democratic places of learning: The Gulf Island Film and Television School

By: Juan Carlos Castro & Kit Grauer

It is Monday, halfway through the first day of the Youth Media Intensive week-long workshop during spring break at the Gulf Island Film and Television School (GIFTS). Peter Campbell, the mentor for the week, is asking 17 students: “What is your log line?”

Log lines are short, one- or two-sentence descriptions of an idea for a film. The scenario that Peter sets up reproduces what professional script writers would do in the film and television industry—pitch ideas back and forth, entertaining the interesting ones, picking them apart, and asking tough questions. This activity produces an intensive learning and professional creative environment with the group of 17 teens, ages 13 to 19. The curriculum and pedagogy of GIFTS seeks to create a place where the ideas of individuals become collective ideas. By Saturday the group of 17 divided into smaller groups; chose a log line to develop into a script for a 3- to 7-minute film; and learned basic video production including visual composition and storytelling, acting for the camera, sound recording, video and sound editing, and post-production techniques. GIFTS is a community-based new media school founded 15 years ago by a group of documentary and commercial filmmakers on the site of a former logging camp on the island of Galiano in British Columbia, Canada. This article presents insights derived from a component of a larger research project

investigating community-based new media education centers. Specifically, we address these two questions from our time spent investigating GIFTS: (1) What can we learn about art, and especially new media teaching and learning, from alternative sites like GIFTS?; and (2) What possibilities for a democratic and socially just arts curriculum and pedagogy can be learned from a place like GIFTS? It is not enough to merely teach ideas about democracy; they must be embodied in our art curricula and pedagogies. Places such as GIFTS offer insights into possibilities for structuring curricular and pedagogical experiences that use new media and foster democratic practice—communication, collaboration, and collective problem solving. Additionally, we argue that as new media practice, especially filmmaking and video arts, becomes more common in art classrooms (Szekely & Szekely, 2005), K-12 art educators can draw from the curricula and pedagogies from places like GIFTS.

image A ferry approaches the Sturdies Bay. Photograph by Juan Carlos Castro.

15 14 15

Occurring after school or during holidays, these communitybased new media programs have become increasingly common (Goldfarb, 2002; Goodman, 2003; Tyner, 1998). The varied media ecologies in which young people participate have been regarded as both compelling modes of entertainment and powerful means of education. Media ecologies are buttressing and interdependent media that support and integrate with each other dynamically, without canceling each other out (McLuhan, 2005). Community-based programs like GIFTS function largely outside of formal school settings and approach media education from a professional production focus that seeks to foster self-expression, creativity, critical analysis, and the development of identity and voice. As an alternate learning environment, GIFTS offers important pedagogical dimensions to evolving contemporary media ecologies. With teens regularly participating in and through participatory cultures in virtual worlds (Jenkins, Clinton, Purushotma, Robison, & Weigel, 2007), it is also apparent that embodied participation, or gathering

together in real time or space, to engage in new-media production can also be an important aspect of the expanding new media ecologies. Community-based programs provide spaces for meaningful face-to-face encounters to happen and foster democratic skills such as collaboration, communication, and collective problem-solving. Community-based programs can also be seen to occupy a “third arena� between school and family, where young people are afforded learning opportunities that are unavailable in either context (Kangisser, 1999). Richards (1998) has pointed to the more flexible and democratic structures of curriculum and pedagogy in community-based settings as a distinct advantage for youth engagement and learning. This democratic curriculum and pedagogy is embodied in the media workshops at GIFTS.

Structuring Democratic Curricula and Pedagogies There has been an increasing call for art educators to teach for democratic values and social justice in their classrooms (Carlson

Ar t E du cati on [ S eptemb er 20 10 ]

Community-Based Media Arts Centers

& Apple, 1998; Darts, 2004, 2006; Desai & Chalmers, 2007; Freire, 1997; GaztambideFernandez & Sears, 2004). As educators, we share the view that imparting such values seems to be of utmost importance. On one hand it is important to teach the values of democracy and of treating each other with respect and dignity. On the other, it is equally imperative that educators ensure that their teaching of such ideas is not undermined by a curricular structure and pedagogical approach that creates its own systems of oppression. In a typical week at GIFTS, during students’ spring break or in summer media-intensive courses, one usually would not hear the words “democracy” or “social justice” spoken. Yet under the pressure of having to work together to fully conceptualize, script, act, shoot, edit, and produce a short film, students are learning how to collaborate, compromise, and communicate. These are foundations of what it means to live in a democratic society. Far from experiencing a seamless process of collaboration, students are continually confronted with struggles, tension, and difference. It is in this third and transformational place that students learn what it means to believe in something together to be able to collaborate, compromise, and communicate around a shared project. Filmmaking differs from traditional media processes such as painting in that it is not a solitary task of creating. It often involves the clashing of egos, which creates tension and a

top Most of the social interaction occurs in the common courtyard area. The large building at the far end is the main classroom. To both sides are student dorm rooms for the in-residence camp.

bottom The entrance to GULFS, located on the site of a former logging camp on Galiano Island, British Columbia, Canada. Photographs by Juan Carlos Castro.

constant struggle to have one’s ideas heard. This is important for classroom art educators to pay attention to as creative practices shift through new media to more participatory activities (Jenkins et al., 2007).

Third pedagogical sites are distinguished by fluidity and permeability which allow the boundaries of the world of professional artmaking to blur with that of conventional schooling. GIFTS embodies these qualities: it is neither a traditional schooling environment nor a professional film set, but something in-between. It is a transformative place, not only for the students but also for the mentors themselves. Heath (2001) stated that the

Ar t E du cati on [ S eptemb er 20 10 ]

curriculum, pedagogy, and place enable a freedom that comes with considerable responsibility. From how the mentors and interns address students to how staff interact, there is a sense of shared responsibility to helping students not only make films, but make change. Students are expected to respect each other while also contributing to being part of a team, taking on multiple roles with the ultimate goal of making a film by the end of the week. This is a third site—one where students can enter, construct, and present an identity, not without constraints but with a

Creating a place for learning, one that is outside of the bounds of everyday schooling experiences and connects to the lives of our students, is a possibility that needs to be considered in discussions of K-12 art classrooms. Brent Wilson (2008) described a third pedagogical site as a “life-changing space where new forms of hybrid visual cultural artifacts, production, and meaning arise through informal contacts among kids and adults” (p. 120). Such productive informal contact is characteristic of GIFTS: although initially formal, boundaries between mentors, interns, technical assistants, and students at GIFTS is initially formal, those boundaries between their respective roles are fluid and ever-shifting throughout the week.

17

GIFTS was founded on principles of nonviolent communication and filmmaking: both the act of making films and of working together to be able to communicate and collaborate.

A Third Place for Learning 17 16

GIFTS was founded on principles of nonviolent communication and filmmaking: both the act of making films and of working together to be able to communicate and collaborate. The

purpose, to work together not only on making a film but on how to communicate, compromise, and collectively problem solve.

value of these places of learning is that they “enlist young people in meaningful planning, assumption of “real” roles in organization and management, and sustained focus on details critical to quality-level long-term production” (p. 10). The professional-like working environment, complete with professional expectations, identities, and histories, serves both as a support and as constraints that enable, thereby providing a transformational experience for students.

Transformational Places of Learning Places of learning, as described by Elisabeth Ellsworth (2005), are where and when “[e]verything we ‘know,’ everything that is ‘tellable,’ emerges out of the time and place of this embodied movement/sensation—which is also a time and place of self-dissolution” (p. 167). Dissolution means a moment when the binary of self/other are smudged. What places of learning do, according to Ellsworth, is create a place of dissolution in which the “I” reemerges, changed through the experience. The binary of self/other is transformed. When students walk off the ferry and are transported to the remote camp they are able both to take on a new role and also to have no preconceptions on building relationships with their fellow students. The self/other binary is blurred to become terms such as community, family, team, and film crew. There are no other distractions and no other reminders about who they were and the contexts they came from. It is a chance to perform themselves anew. The social bonding and transformation that occurs between participants is not without its own tensions and struggles while students work to remake their identities in communication and collaboration with each other. Tension erupts as ideas for films are negotiated and roles such as director, editor, and sound grip are traded, shifted, and cycled through during the week. Mentors constantly point to the constraint of time to remind students that it is the deadline they need to work against, not each other.

Communication and Collaboration Essential to making a place like GIFTS a successful learning environment is the teaching of communication tools used in filmmaking, which enables successful collaboration. These tools include scripts, storyboards, shot lists, and meetings. By the end of the week most students have lived and worked intimately together, shooting all day and editing through the night. Some decisions have been fought over and some agreed upon with a simple nod of the head. As a team they learn how to work together toward a common goal and use the tools of communication taught by the mentors in addition to those they have developed on their own. Students speak about the roles that they are assigned and how they adapt to their roles and negotiate new ones. They also speak about how their roles are fluid: each is encouraged to be a director, work on sound, or work the camera, and each can have a hand at trying out each other’s roles. As shooting begins, mentors are observed as they are getting involved, picking up a boom, wrapping cables, and even washing dishes after lunch

without being prompted or asked. It is the development of a “shorthand,” so that each individual can communicate effectively, that makes it possible to work together. Absent from GIFTS are titles like Teacher, Ms., or Mr. There is no one labeled as teacher at GIFTS. Instead, the title of mentor is assigned to the person who would traditionally be called a teacher. However, the mentors are not trained as teachers; they are usually professional filmmakers. Part of making GIFTS a third site of learning is stripping away the formalities of schooling. The goal is to make a film in a week; this liberates mentors to not dictate what ideas students explore, but to point towards possibilities to consider and pitfalls to avoid. The constraints of having to make a film in a week enable the possibility of taking on a decentralized role in the learning. The mentors treat students as professionals and teach them the vocabulary and practices of filmmaking. By the end of their experience, students understand that mentors are not like their teachers at school. Mentors at the beginning of the week are often seen and treated as teachers; as the week unfolds their identities shift as they become collaborators and eventually fade into the background. Mentors do not limit what students wish to attempt. Rather, they say things like: “Have you considered this? What’s your log line? How will you communicate this idea visually? How will you get that shot? With this much dialogue in your script, it might not be possible to find an actor on the island who can do this.” Because the mentors have the experience of making many films and seeing the process unfold over and over, they can ask questions, make statements, and offer prompts—not to shut down students or give them easy solutions, but rather to point toward possibilities and pitfalls of working in their contexts and with their ideas. What can we, as art teachers, learn from places like GIFTS? One of the goals of this study was to look at these third pedagogical places to find different ways of thinking about teaching and learning in public school art classrooms. Many things happen at GIFTS that are just not possible in art classrooms. However, a number of salient insights into how teens learn and what they respond to can be incorporated into our classroom for more democratic practice.

Constraints That Enable: Productive Tension We operate in the world under constraints. There are basic physical constraints such as gravity, financial constraints such as funding, and time constraints such as project deadlines. Without constraints in our lives there would be too many possibilities to choose from: limitless options leading to inaction. There are constraints that come from outside of our everyday lives and there are those that are part of the contexts we live in and engage with. At GIFTS, there is the meta-constraint of time: having to conceptualize, script, act, shoot, edit, and produce a film in a week. The constraint of time is always pointed at by the mentors as a reason to work through problems, tensions, and even fatigue. The responsibility is put on the students to

above Warren Arcan gives a student feedback about his script ideas.

below right Disembarking the ferry at Sturdies Bay, Galiano Island. Photographs by Juan Carlos Castro.

below center The video editing studios at GIFTS.

below left Group meetings are common throughout a Youth Media Intensive workshop.

19 18

Sense of Agency | It is through the constraints of time and of having their ideas subjected to a level of productive and supportive critical development that students at GIFTS gain a sense of agency. Agency is defined here as a freedom to act from an understanding that students are depended on and can have an effect not only on their peers, but the working environment, the mentors, and the final product. It is a sense that what they do matters, not only to them but to each other.

Teaching as Pointing Toward Possibilities and Pitfalls | The etymology of the word teach comes from the root taecan, meaning “to show,” “present,” and “point out.” Mentors often talk about not knowing what ideas students will want to explore in their films. They focus not on what they can do to prepare, but on how they can respond. Mentors draw from their vast and deep knowledge of working as filmmakers to ask those tough questions, to articulate the constraints they are working under, to point out the possibilities and pitfalls of how students might bring their ideas to the screen. The mentors at GIFTS improvise to meet needs of the individual and the collective, striking a delicate balance between making sure ideas are heard and valued while ensuring there is movement towards the group’s goals throughout this intense week. As art teachers, we can similarly shift the responsibility for the ideas explored to students while drawing from our own experiences of artistic inquiry.

Ar t E du cati on [ S eptemb er 20 10 ]

Classroom art teachers can point toward such productive constraints—such as a group exhibition, a scholarship, or a contest outside of the school—to move the why of making art from “because my art teacher wants it” toward “because we have a shared goal to meet.” Like the mentors at GIFTS, art teachers can move from the center—not bearing any less responsibility, but shifting the role of teacher as giving knowledge to that of pointing toward the possibilities and pitfalls ahead.

Art teachers will always have to work with a level of responsibility in the classroom, yet they do not have to be in the center of ideation, production, and exhibition. It is about creating a place where a shared project of inquiry in which every student feels they have a say and stake, whether it is working in a small group to make a film, or as an individual painter to contribute to a group exhibition. They are depended on to contribute.

19

meet the challenge of making a film in a week. GIFTS students’ collective stake in the final screening of their films is not the only constraint that enables them to care deeply about their films. It starts on the first day, when students are asked: “What’s your log line?” From that moment onward, it is about their goals and ideas. Students are not told what ideas to explore; they are asked tough questions about their ideas, and, through a looping process of idea-pitching, to question and rework to another pitch, students’ ideas are tested, questioned, and refined. In the end, it is their ideas brought to life on the screen.

Summary GIFTS students remark that mentors are not like their teachers at school. Anna C.,¹ a student and member of a documentary team, remarked that their mentor, Liam Walsh, “had his ideas and he didn’t force them on us.” When asked to elaborate, especially about how this could translate for teachers in schools, she said: have it a circle, don’t have the teacher as the main point of focus… don’t be pressing the gas and steering. Just put road signs out that say: if you want to do this, take this road… if you want to try it and you don’t like it, there’s always a u-turn, right? Don’t be stuck in your ideas and your thoughts and beliefs, because not everyone will have that and even… and you can’t force it on people, so don’t. (Anna C., GIFTS student, personal communication, August 22, 2008). Places like GIFTS are instructive for art teachers—not to, as Heath (2001) warns, “become the source of one more ‘to-do’ mandate for their classrooms” (p. 15). Rather, the value of such third pedagogical places of learning is in the lessons they offer for creating a democratic place where the curriculum and pedagogy foster communication, collaboration, and collective problem solving. It is the shared belief in the process of artistic inquiry, not just individually but collectively. Places like GIFTS stand as examples of the learning potential of structuring our curricula and pedagogy to be more democratic in its enactment.

Endnote ¹ Participants in our study were required to sign a consent form (for participants over 18 years old) or assent forms (for participants under the age of 18 years old). Participants under the age of 18 were required to have a signed parental consent. Due to the public nature of participants’ artistic productions they were given the option to have all of their videos, interviews, and images attributed to themselves. Anna and her parents assented and consented to having her identity attributed to her artistic productions, interviews and images. Her documentary group’s film on gaming can be accessed at http://www.youtube.com watch?v=SOyemamCXxU.

Authors’ Note We gratefully acknowledge financial support of this research through a Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Grant (Kit Grauer, principal investigator; Sandra Weber, co-investigator; and Anita Sinner, collaborator).

“Don’t be stuck in your ideas and your thoughts and beliefs, because not everyone will have that… and you can’t force it on people, so don’t.”

below The countdown clock which charts the flow of production in a typical GIFTS course. It is located outside of the main classroom in the common courtyard area. Photographs by Juan Carlos Castro.

left Liam Walsh works with students in the editing room.

20

Juan Carlos Castro is Assistant Professor of Art Education at Concordia University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. E-mail: juan@juancarloscastro.com Kit Grauer is Associate Professor of Art Education at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. E-mail: Kit.grauer@ubc.ca

Heath, S. B. (2001). Three’s not a crowd: Plans, roles, and focus in the arts. Educational Researcher, 30(7), 10-17. doi:10.3102/0013189X030007010 Kangisser, D. (1999). The third arena: After school youth literacy programs. New York: Robert Browne Foundation. Jenkins, H., Clinton, K., Purushotma, R., Robison, A. J., & Weigel, M. (2007). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st century. Retrieved from http://www.digitallearning.macfound.org/atf/ cf/%7B7E45C7E0-A3E0-4B89-AC9C-E807E1B0AE4E%7D/JENKINS_ WHITE_PAPER.PDF McLuhan, M. (2005). Understanding me: Lectures and interviews. S. McLuhan & D. Staines (Eds.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Richards, C. (1998). Beyond classroom culture. In D. Buckingham (Ed.). Teaching popular culture: Beyond radical pedagogy. London: UCL Press. Szekely, G., & Szekely, I. (2005). Video art for the classroom. National Art Education Association. Tyner, K. (1998). Literacy in a digital age: Teaching and learning in the age of information. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Wilson, B. (2008). Research at the margins of schooling: Biographical inquiry and third-site pedagogy. International Journal of Education through Art, 4(2), 119-130. doi:10.1386

Ar t E du cati on [ S eptemb er 20 10 ]

Carlson, D., & Apple, M. W. (1998). Power, knowledge, pedagogy: The meaning of democratic education in unsettling times. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Darts, D. (2004). Visual culture jam: Art, pedagogy and creative resistance [microform]. Vancouver: University of British Columbia. Darts, D. (2006). Art education for a change: Contemporary issues in the visual arts. Art Education, 59(5), 6-12. Desai, D., & Chalmers, F. G. (2007). Notes for a dialogue on art education in critical times. Art Education, 60(5), 6-11. Ellsworth, E. (2005). Places of learning: Media, architecture, pedagogy. New York: RoutledgeFalmer. Freire, P. (1997). Pedagogy of the oppressed (20th-anniversary ed.). New York: Continuum. Gaztambide-Fernandez, R. A., & Sears, J. T. (2004). Curriculum work as a public moral enterprise. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Goldfarb, B. (2002). Visual pedagogy: Media cultures in and beyond the classroom. Durham: Duke University Press. Goodman, S. (2003). Teaching youth media: A critical guide to literacy, video production, and social change. New York: Teachers College Press.

21

References

the challenge of new

colorblind racism in art education

By: Dipti Desai

The election of Barack Obama, the first African American President of the United States, is undoubtedly historic. Many of us, both people of color and White were deeply moved the night of the election. In New York City, where I live, and around the country and globe, celebrations broke out and people took to the streets reveling in the beginning of a new age. Immediately, news commentators and media pundits proclaimed that we had entered a post-racial era. This view that an Obama victory would signal the end of racial inequality was a major concern of several Black intellectuals and bloggers who supported Obama prior to the election. Lawrence Bobo, a Black sociologist, said “If Obama becomes the president, every remaining powerfully felt [B]lack grievance and every still deeply etched injustice will be cast out of the realm of polite discourse” (Swarns, 2008, p. 1). Mr. Obama was clearly aware that his candidacy or election would not solve the nation’s racial inequities. His March 2008 speech was the only one to address race directly. According to Glen Ford (2008), the Obama Campaign was “relentlessly sending out signals to [W]hite people that a vote for Barack Obama, an Obama presidency, would signal the beginning of the end of [B] lack-specific agitation, that it would take race discourse off of the table”(¶ 11). Perceptions and beliefs of racial inequality vary widely between Blacks and Whites (New York Times /CBS News poll, 2008).

As art educators who work with the next generation of teachers, we need to pay close attention to this disparity as it speaks to the racial divide that colors the experiences of students from public schools to universities. In public education today, we are faced with three interconnected realities: (1) the majority of teachers are white, middle class, and female; (2) our student body is racially diverse and the rapidly changing demographics point to an increase in students of color; and (3) students of color are more at risk of failing in our schools. This new reality suggests that art teacher education needs to directly address racial inequality. In this article, I examine the ways the colorblind ideology shapes our post-Civil Rights society, what is now being called the new racism. I look specifically at the ways colorblind ideology is produced and reinforced through multiculturalism and visual culture (media). I then look at how it shapes art teachers’ understanding of racism. Drawing on the work of several contemporary artists who challenge the colorblind ideology, I argue that through new representations of race/racism in the art-world, media, and classrooms we can shape anti-bias art education practices.

Racial Inequality in the Age of Obama We are not in a post-racial era. The gap between Whites and people of color continues to grow in education, health care, income, unemployment, and incarceration (see Figure 1). It is clear then that racism is still endemic to our society. As Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (2004) explains “Racism springs not from the heart of ‘racists’,” but from the fact that dominant actors in a racialized social system receive benefits at all levels (political, economic, social, and even psychological), whereas subordinate actors do not” (p. 558).

figure 1 Chart Based on National Urban League’s 2009 The Equality Index that is part of their report titled State of Black America and 2009 Bureau of Justice Statistics Report.

Median Household Income

Unemployment

Without Health Insurance

Incarcerations

Hispanics

$37, 913

12.1%

30.7%

2.4% Hispanic Males

Whites

$55, 530

8.5%

10.8%

0.8% White Males

Blacks

$34, 218

14.8%

19.1%

4.6% Black Males

Art educators who work in teacher education must examine the new colorblind racism that frames our understanding of difference in order to challenge racist practices in our schools and communities. This honest examination is required if we are to address what the playwright Anna Deavere Smith (1993)calls “our struggle to be together in our differences” (p. xii). Each year in my university classes, I witness the deep racial divide between students of color and White students. White students are annoyed when students of color challenge their colorblindness. These challenges inevitably lead to heated and emotional charged discussions about race and racism. Students of color, on the other hand, avoid confronting racist discourses and often remain quiet—perhaps something they learned to do from a very young age. Talking about racism is difficult, painful, and emotional. Vastly different lived experiences inform students’

Ar t E du cati on [ S eptemb er 20 10 ]

The dominant narrative of the post-Civil Rights era is the notion of color blindness, which is an important component of what sociologists are calling the new racism. Shaped by the liberal discourse of individualism, freedom and opportunity, contemporary racism is described as laissez faire racism (Bobo, Kuegel, & Smith, 1997) or colorblind racism (Bonilla-Silva, 2001). Despite differences in the terms used to describe our current racial condition, broadly speaking, the beliefs and views that frame contemporary discourses on race include the notions that (1) people of color should pull themselves up by their bootstraps,

Colorblind racism, according to Bonilla-Silva (2001, 2004), involves: (1) an increase in covert racial discourses and practices; (2) avoidance of racial terms and claims by Whites that they experience reverse racism; (3) language or “semantic moves” that avoid direct racial references in order to safely express racial views; and (4) invisibility regarding the mechanisms of racial inequality. To speak about new racism does not mean we have not made advances regarding race relations since the Civil Rights movement. We have. However, as a nation and certainly in our schools we tend to avoid meaningful discussion about racism.

23

Seeing Colorblindness

implying that they are unmotivated; (2) discrimination is not the cause of racial inequality; (3) government gives too much attention to race and gives too many opportunities to people of color and not to Whites; (4) people of color are to blame for the persistent gaps in socio-economic conditions and in education; (5) race is no longer an issue; (6) Whites face reverse racism; and (7) people of color tend to use the race card to their advantage.

23 22

For several years now I, among other art educators, have written about the ways the institutionalization of multiculturalism has perpetuated racism by reinforcing the idea of a colorblind society. It does this by focusing on culture, ethnicity, and the celebration of diversity (Colins & Sandell, 1992; Ballengee-Morris & Stuhr, 2001, Desai, 2008, 2005, 2000; Wasson, Stuhr, & Petrovich-Mwanki, 1990). Multiculturalism as enacted in a majority of elementary and high school art classrooms is about tolerating diversity, which has led to the marketing of difference in particular ways, rendering invisible the racialization of punishment, immigration, schooling, art practices, and media. The growth of multiculturalism (schools to corporations) implies that we have “‘overcome’ racism without necessarily shaking up the power structures that are expressed through and that constitute the social context of racism” (Davis, 1996, p. 43). The underlying assumption is that difference can be understood by acquiring knowledge about it and this knowledge will erase racial inequality. However, as Angela Davis (1996) states, “Policies of enlightenment by themselves do not necessarily lead to radical transformations of power structures” (p. 47).

understandings of racial inequality. For many of my White students, their experience of difference is experiential, as they grew up in White suburbs and attended K-12 schools where the majority of students were White. Even those White students who grew up in major cities experienced racial segregation. They typically attended city schools with a high percentage of White students. Many White students’ understandings of difference are based on popular culture and media images that promote racial inequality as a thing of the past. They grew up seeing images and often stereotypes of African Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans in the media and in advertisements on a daily basis. Our visual culture continues to reproduce colorblind racism by naturalizing and normalizing images of racial difference in the name of cultural diversity.

Visual Culture and Colorblind Racism Popular magazines and the media are important pedagogical spaces (Giroux, 2006) as they provide the first lessons on colorblind racism. I use both visual culture and contemporary art to start conversations about how race relations are part of our daily lives and how these experiences shape our values and beliefs about different racial groups. One project my students undertake is to analyze contemporary cultural products (TV shows, films, paintings, shoes, advertisements) that have stirred racial controversy. They explore the ways colorblind ideology is shaped or negated through the various discourses circulated about a cultural product. This then opens ways of understanding how discourses in our cultural landscapes are racialized. For example, the April 2008 Vogue magazine featured for the first time on its cover a photograph of an African American man, Lebron James, with top model Gisele Bündchen. This image sparked a major controversy exposing the fault-lines of race relations in the United States, as the cover portrays Lebron James in an ape-like stance, bearing his teeth while simultaneously clutching a petite white model, Gisele Bündchen, recalling images of King Kong. Similarly, Adidas introduced a new line of trainer shoes called the “Yellow Series” that represented a stereotypical cartoon image of an “Asian youth with bowl-cut hair, pig nose and buck teeth” (n.a. 2006, ¶ 1). This image offended many

Asian Americans, but Adidas contended that the artist Barry McGee created this image as an anti-racist commentary. Disney, one of the most powerful oligopolies in the world, is a cherished part of childhood experiences in the United States, shaping understandings of social relations as normative and given, rather than constructed. Disney images represent dominant ideas of race, gender, sexuality and social class (Tavin & Anderson, 2003). Naomi Klein (1999) writes that “Disney has achieved the ultimate goal of lifestyle branding: for the brand to become lifestyle itself ” (p. 155). Most Disney shows over-simplify the complexities of race/racism and neutralize it through colorblind ideologies. In February 2005, Disney Channel aired “True Color” the 53rd episode of its longest-running sitcom, That’s So Raven, which was nominated for an Emmy Award and praised for its portrayal of African Americans. The episode, despite its African American cast, stopped short of addressing the political landscape of race/racism that permeates our society by limiting the discussion of race to one episode, thereby relegating challenges to dominant culture to the margins (Tavin & Anderson, 2003). Another media example is the award-wining movie Crash, directed by Paul Haggis. This movie caught our culture’s imagination and has been hailed as a true post 9/11 representation of the complexity of race relation’s in our country. From high schools to universities, Crash is widely used in classrooms to address race-relations. “Crash is eminently pedagogical. It clearly attempts to teach the viewer something about race and racism” (Howard & Dei, 2008, p. 4). The teachings regarding race, however are ultimately about individuals and their prejudices across the racial spectrum, leaving one with the message that racism is an individual and not systemic issue. As the editors of the book Crash Politics and Antiracism: Interrogations of Liberal Race Discourse, Howard and Dei state, “What is interesting about this movie, however, is that while to many it purports to say something new, anti-racist and anti-colonial analyses reveal that it plays directly, with almost no deviations, into dominant oppressive, Eurocentric, and white supremacist discourses of race” (p. 4). Our students need to develop racial literacy to identify and critique racial discourse in popular culture, media and other sites of visual

figure 2 Shepard Fairey stickers on a date book.

The Obama campaign strategically used the colorblind ideology to gain support, especially in swing states: “Obama’s appeal among white Americans, its seems rests on his perceived ability to transcend race—that is, not to be a [B]lack candidate but simply an American one…” (Mazama, 2007, p. 3).

Similar to critical pedagogical practices, contemporary artists pose questions that prod us to examine taken-for-granted ideas about race, racism and whiteness. These questions allow us to begin the process of thinking critically about how our experiences are shaped by our social position, which is always informed by history. Much of the work done by contemporary artists of color who examine race, racism, and whiteness situate their work within a historical context—thereby challenging an a-historical analysis of policies, laws and institutions that is perpetuated by our educational system. Their work asks viewers to consider their social position in relation to our history. One of the main reasons for colorblind racism is the lack of knowledge and understanding about the history of race and racism in the United States. I often show my students two brief episodes of the PBS series Race: The Power of an Illusion in which Harris (1993) argues that “Whiteness” became property; one that holds tremendous value both materially and symbolically. The normalization of whiteness produces the colorblind ideology. Exploring the notion of colorblindness, Diggs (2009) created a public art project called “ Face” that was intended to open dialogue about race relations at Williams College, where in the spring of 2008 a major bias incident took place (see Figure 3). Students at Williams asked to focus on race relations for a

Ar t E du cati on [ S eptemb er 20 10 ]

A recent visual culture site that needs examination is the new genre of Obama art that is truly historic. Art scholar Steven Heller (2008) states, “Never, as far as I can tell, in the history of a presidential campaigns has such a huge out-pouring of independent posters been created for a single candidate” (¶ 1). Obama’s race as well as his message of hope and change were factors that inspired many artists. Yet, the majority of artists de-emphasized Obama’s race, rarely depicting his skin color. The most famous example of Obama art that captured the nation and world is the ubiquitous red, white, and blue posters of Obama inscripted with the words “hope” or “progress” and reprinted on buttons, stickers and T-shirts (see Figure 2).

Reframing Race through Contemporary Art

25

to reproduce colorblind racism by naturalizing and normalizing images of racial difference in the name of cultural diversity.

On the other hand, the work of African American graphic designer Ray Noland, the first artist to create and promote Obama art, did not appear to appeal to the masses. Noland represented Obama as part of an African American discourse both ideologically and aesthetically by consciously depicting him in variations of brown. In one poster he uses basketball imagery and in some other posters he is shown among bullhorns and a mass of protesters holding picket signs repudiating the Iraq war. 25 24