11 minute read

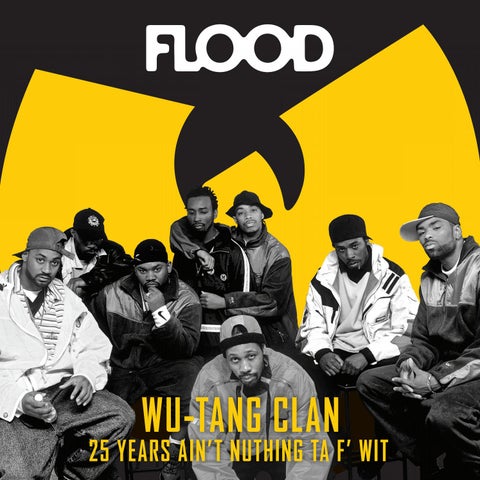

Wu-Tang Clan: Twenty-Five Years Ain't Nuthing Ta F' Wit

A quarter-century after 36 Chambers, Wu-Tang has become one of rap’s most surprising and enduring success stories. Here, RZA, Method Man, U-God, Masta Killa, and Inspectah Deck guide us through the life of Wu, and give an account of how failure, focus, and perseverance helped earn them a religious following.

BY SOREN BAKER

GZA

By Michael Wong

RZA

By Michael Wong

GZA and RZA responded to their early musical setbacks differently.

In 1991, rap was largely raucous, ribald, and raw. N.W.A, Ice Cube, Public Enemy, Geto Boys, DJ Quik, Cypress Hill, and Ice-T dominated the landscape with brutal, politically minded, and salacious tales of the streets, of a corrupt America, of unending violence. But the initial forays into music from future Wu-Tang Clan members GZA and RZA were anything but raucous, ribald, or raw.

GZA’s debut album, 1991’s Words from the Genius, floundered after its intended crossover single “Come Do Me” failed to connect with audiences. Although the fifteen-cut collection from Cold Chillin’ Records (then home of rap stars Biz Markie and Big Daddy Kane) became an underground favorite of sorts—thanks to GZA’s street-based narratives on such songs as “Life of a Drug Dealer” and “Drama”—The Genius, as GZA was then known, grew discouraged, got a job as a bike messenger, and virtually stopped recording.

For his part, RZA (then going as Prince Rakeem) endured a similar fate with “Ooh I Love You Rakeem,” a popish 1991 single on Tommy Boy Records that didn’t reflect RZA’s personality.

“Tommy Boy didn’t see in me what I saw in me at that time,” RZA says today. “They saw maybe what I saw when I was nine years old—more of a certain kind of kid. But I was not that guy then. I was strictly Timberland, rough, chop your head off—that was my personality, my energy. And maybe because the Will Smiths were the strength and the power of the hip-hop industry, they felt I could fit in that field as some kind of cute guy.”

It didn’t work. After GZA and RZA’s material was released, they abandoned their respective labels with little fanfare.

But for the members of what would become the Wu-Tang Clan, GZA and RZA had broken through. “For us, it was success because they came from the block we came from,” Inspectah Deck says. “While Kool G Rap’s ‘Road to the Riches’ got big, we had ‘Life of a Drug Dealer.’ So they were famous and big-time in our eyes regardless, because it was like Staten Island’s own.”

“I was RZA and GZA’s biggest fan,” U-God adds of the pre–Wu-Tang Clan era. “We still saluted them and thought they were the illest. That’s just how it was. That was our Rakim, our Biz Markie. They were our shining lights, our examples.”

This was also long before the Internet became ubiquitous and social media rose to prominence. Thus, when Masta Killa met GZA, he didn’t know he was a recording artist.

But where GZA had largely retreated from the music industry, RZA used his experience to pave the way for what the Wu-Tang Clan would become. He learned from his one-time manager Melquan Smith, as well as Melquan’s father James Smith, how to run an independent label— Yamak-Ka Records in their case—which released material from the rap group Divine Force. From Tommy Boy, RZA learned the importance of networking and being business-minded at all times.

“It was Mr. [James] Smith’s knowledge that gave me the idea of forming my own record company, forming Wu-Tang Productions, making my own records, spending my own money, doing it, and selling it right out of my house,” RZA says. “Tommy Boy provided me [the opportunity] to travel, to get to see other emcees work. Getting to see that industry thing gave me the chance to develop that business personality.”

He continues: “I had enough consciousness and relationships to know that as my own businessman, like Mr. Smith was, I should be able to guide my own path. Experience can be the best teacher, even the experience of failure.”

Ghostface Killah

By Bob Berg

Ol' Dirty Bastard

By Bob Berg

Method Man

By Bob Berg

Inspectah Deck

By Michael Wong

Masta Killa

By Michael Wong

Raekwon

By Michael Wong

U-God

By Michael Wong

When GZA and Masta Killa were developing their friendship in Brooklyn, they bonded over chess and the Nation of Gods and Earths, a mystic movement espousing the belief that only a small portion of the population knows the truth of existence. More of a reggae fan at the time, Masta Killa had rebuffed GZA’s invitations to go with him to the studio. Then GZA played Masta Killa some music from his crew, which was based in Staten Island.

“He put the tape on, and it wasn’t even completed yet, but it was ‘Protect Ya Neck,’” Masta Killa remembers. “When I heard ‘I smoke on the mic like Smokin’ Joe Frazier, the hell-raiser,’ I was like, ‘What the fuck?’ He was like, ‘Yeah. This is what I do. That’s why I was telling you to come. These are my Shaolin Brothers.’ I was like, ‘Oh, shit. Now I get it.’”

Now in the fold, Masta Killa joined RZA, GZA, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, Method Man, Inspectah Deck, U-God, Raekwon, and Ghostface Killah to form the Wu-Tang Clan. As they worked on Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), the group’s now-famous blend of martial arts, the teachings of the Nation of Gods and Earths, larger-thanlife personalities, grimy soundscapes, and witty wordplay created a mystery of sorts surrounding them. Even the members themselves didn’t know quite what was developing.

“Going into making that album, it didn’t feel like we was making an album,” Method Man says. “We didn’t get to hear it until it was actually done done. We didn’t get an advance copy, none of that shit. RZA was very tight with everything. He didn’t want shit to get stolen because all kinds of shit was going on. When I heard it, the way he put that shit together, it didn’t sound like anything else I had heard before. Anything. Up to that point, most of the albums I was getting, they would have one or two songs on there that were great. The rest of them were just filler. That was a rap album to me. This had song after song. Even the songs I didn’t like, the fans liked. It just boggled the mind.”

Early on, it was clear that the Wu-Tang Clan was about more than music. It was a movement—a brotherhood— that was slowly revealed as the group independently released “Protect Ya Neck” and then Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) on Loud Records in 1993. The group took the unusual step of not showing their faces on the LP’s cover art.

“It just showed that we weren’t looking for fame,” Inspectah Deck says. “It wasn’t like, ‘Yo, I need my face seen ’cause I’m cool and I want everybody at school to know it’s me.’ Nah. It helped to create that mystique of who these dudes was. Nobody knew who we was, but they heard the music. They heard ‘Protect Ya Neck’ and these karate chops. They were like, ‘Yo, these mothafuckas go hard on the mic, but they sound different from everybody else.’ It made you want to check. You can’t see those faces. You don’t know who’s who.”

The video for “Protect Ya Neck” was striking in its simplicity, even for the time. A gritty compilation of shots of the group in and around the Park Hill Projects in Staten Island, the clip also features group members brandishing swords, and RZA holding a Bible during his verse. Several of the group’s disparate influences were immediately on display: the streets, religion, and martial arts.

At the same time, the song and video were a lot to digest in less than five minutes, with eight rappers delivering hard-hitting verses. (Only Masta Killa, who wasn’t yet in the group, did not appear on the song.) Method Man likens the early fascination with the group to what he calls “The Five Deadly Venoms/Magnificent Seven/Seven Samurai Effect”—the way fans rally around a group of people fighting for a common cause. Wu-Tang Clan had, in effect, created its own society of sorts, complete with its own culture and language. The phenomenon quickly built on and sustained itself.

“It started off with, ‘Do you know who the members are?’” Method Man says. “OK. That’s the mystery off top right there. ‘How many members do they got?’ Then when you start hearing the names, it’s like, ‘Oh shit. These dudes is colorful.’ Then it was like, ‘Do you know about the philosophy—the thirty-six chambers and where that comes from?’” [Editor’s note: Nine members = nine hearts. Four chambers to each heart = thirty-six chambers.] “Then there was the whole infatuation with the Nation of Gods and Earths. If you were up on Wu-Tang, it was like an inside joke, and you were in on the joke.”

As 36 Chambers singles “Da Mystery of Chessboxin’,” “Can It Be All So Simple,” “C.R.E.A.M.,” and “Method Man” were released, the group’s mystery was balanced by its inclusionary tactics. On “Wu-Tang Clan Ain’t Nuthing ta F’ Wit,” for instance, RZA concluded the song by shouting out cities, regions, and HBCUs. “RZA was naming all those places, and people took that for real, like, ‘He’s shouting us out. We’re Wu-Tang Killa Bees, too,’” Inspectah Deck says. “We allow people to feel like it ain’t just us. There’s Wu-Tang Killa Bees in Russia.”

By Michael Lavine

Today, the Wu-Tang Clan and its members have released scores of solo and side projects, collectively selling more than forty million albums. (Sadly, Ol’ Dirty Bastard died in 2004 from drug complications.) Its protégés and associates number in the dozens, while its influence is evident in the careers of Drake, A$AP Rocky, Nicki Minaj, Joey Bada$$, Donald Glover, SZA, and Joey Purp, among others.

“That’s where rap started for me, so it was an honor to have them on my shit,” says Joey Purp, who featured RZA on “Godbody – Pt. 2” and GZA on “In the Morning” on his latest album, QUARTERTHING. “It was the world that they created. They were coming with different styles, coming from different places, creating different worlds, and dropping that science, but putting the medicine in that candy while keeping it funky.”

By Michael Lavine

“It was just slapping,” says JPEGMAFIA, who first came across the Staten Island crew and its “Protect Ya Neck” video while watching a music program on television in the early 2000s. “It was ferocious. At the time, it was like the most demonic thing I’ve ever seen in my life. It was so hard to me. I was like, ‘What the fuck is this?’ It just didn’t make any sense.”

Once he started researching Wu-Tang, JPEGMAFIA quickly became mesmerized. “It felt like rap to me,” he says. “I didn’t know that that’s what that feeling was. Now I know what I was feeling at the time. It was just like, ‘This is it. This is what I see everyday. I love this. This is dirty.’ At the time, I associated groups with *NSYNC, so I was just like, ‘Yo, this is nine niggas and they’re just spitting.’ It was like a reverse boy band.”

“They created this whole universe of this Shaolin style,” says $uicideboy$’s Ruby da Cherry. “Bringing the whole kung fu and martial arts imagery to rap was so fire. I think so many people use that style to this day.”

“I owe them a lot,” Purp adds. “I feel like we all do.”

The Wu-Tang Clan has also remained a collective associated with and influencing much more than music, of course. RZA has emerged as a prominent film and television actor/producer/director/composer. GZA has spoken at Harvard. Raekwon has a wine line ready to debut.

In addition to appearing in the HBO series The Deuce and the Jennifer Garner film Peppermint, Method Man hosts the popular TBS celebrity rap-battle show Drop the Mic with Hailey Baldwin. He believes that the latter, in particular, is helping spread hip-hop culture.

“People that wouldn’t normally even listen to hip-hop records are going back and listening now,” Method Man says. “Molly Ringwald was on the show spittin’, son.”

Inspectah Deck has also enjoyed a robust career and found a different type of musical outlet beyond the Wu-Tang Clan. In addition to his production work, he is one-third of the acclaimed rap group Czarface with 7L and Esoteric.

“Czarface allows me to do everything that I can’t do with Wu-Tang,” Inspectah Deck says. “I can say, ‘Catch me slow dancing with Scarlett Johansson’ with Czarface [on ‘Talk That Talk’]. All the lyrics that I can say in Czarface are pop-culture references. With Wu-Tang, we touch on Knowledge of Self, educating yourself, speaking on world facts. It’s raw hip-hop, straight, uncut. With Czarface, I realize that Esoteric can’t rhyme about the streets and slapping niggas and all that crazy shit that I might and can say.”

U-God found a similarly rewarding way to express himself: by writing a book. His Raw: My Journey Into the Wu-Tang was released in February to favorable reviews. “That book took me two and a half years to write,” he says. “That takes focus—continuous focus. It’s like going in the ring, getting knocked down, and then getting back up. You have no idea how many pages I tore up, how much I had to hide names and move shit around just to preserve certain things. There’s no easy way to do it when you’re creating something. You have to really sit there and take your time to do something and master your craft.”

Twenty-five years after the release of 36 Chambers, the Wu-Tang Clan is one of rap’s most durable groups, a global brand that has penetrated the worlds of music, film, television, and fashion.

“Enter the Wu-Tang, it’s like a flag post,” RZA says. “It’s the measurement of, ‘things were this way before it, and things became this way after it.’ On a music level of hip-hop, and what that movement created, it’s just as important as Obama being the first black president, in my opinion. I say that because it changed so many things after it. With 36 Chambers, it took a whole community and brought it to the surface. We didn’t bring one emcee, or two emcees. With us, it was, ‘Here they are. Here’s your whole fuckin’ neighborhood right in front of you.’”

Soren Baker’s new book The History of Gangster Rap is in stores now.

By Kyle Christy