10 minute read

Men on the Mat

from FLUX 2018

How teachers in Eugene and Springfield are making yoga more accessible

STORY ANNA GLAVASH | PHOTOS MIRANDA DAVIDUK & DANA SPARKS

Advertisement

In a neighborhood gym near the University of Oregon campus, a midday yoga class is in session. Four men and six women bend and stretch to Moby and Bon Iver on jewel-tone mats. Instructor Jess Donohue, 47, is all about encouraging her students. “Let yourself be amazed at what your body can do for you,” she says. “Make it your 100 percent, not your neighbor’s 100 percent. What will make YOU proud?”

The class is called “Broga.” Donohue says her classes are “for the bro in us all.” Yes, it’s branding, but it’s also an approach designed to make yoga more approachable and inclusive when at times it’s anything but.

Yoga is an ancient practice created in India by men, for men. The asanas, or physical poses intended to prepare the body to meditate have become popular in the Western world as a form of exercise. Nearly 30 percent of Americans have tried yoga, according to a 2016 survey of yoga in the United States conducted on behalf of Yoga Alliance. But step into a modern yoga class in Eugene or anywhere in the U.S. and you’ll see a room of mostly women. While the number of men practicing is growing, the survey showed that 72 percent of yoga students identify as female.

Despite these odds, those identifying as men are showing up on yoga mats more and more. Male yoga student ranks grew by 47 percent from 2012 to 2016, from around 19 percent to 28 percent of all students. To encourage this growth, studios and teachers are attempting to remove barriers to entry, such as an exclusive feeling, a spiritual overtone or a focus on flexibility, which affect all genders but can disproportionately affect men.

Broga founder Robert Sidoti says too often men leave class with similar feelings toward yoga: “It’s not for me. It’s for chicks.”

He says men can have different reasons for going to yoga. Picture: “A typical 25-yearold woman offering a yoga class to a group that’s predominantly men in their 40s and 50s, and they’re aching and stressed. She’s talking about the chakras aligning and the heart space opening—these aren’t things that a man wants to hear in that moment. He wants to hear ‘this pose is helping your back feel better. If you keep practicing this, this breathing technique is going to help you manage stress and anxiety.’”

Sidoti came up with Broga 15 years ago in California to cater to men’s needs. In Broga’s curriculum, he relies on “functional movements” and doesn’t teach postures that have no everyday application, which means many of the traditional yoga asanas are thrown away. He says it’s purpose is to “teach and serve yoga up in a way— whether it’s postures, language, purpose or intention—that men can show up for, be open to, digest and process.”

Beyond what benefits are offered in the class, many yoga poses demand a level of flexibility that doesn’t come easily, especially to some men. Jess Donohue is also a massage therapist who’s studied anatomy. Generally, she says male bodies tend to be less flexible than female ones, due to their narrower hips and larger muscles. Teachers don’t always accommodate these differences, making it easy for men to feel like underachievers in a yoga class.

The perceived inaccessibility of Western yoga has been influenced by media representations. On Instagram, yogis tend to model advanced versions of a pose and look serene while doing it. Additionally, men, non-binary people, people of color, older people and a variety of body types have been underrepresented in the media. A campaign called #whatayogilookslike is working toward a more inclusive image. The hashtag has been used more than 19,000 times.

For purists, yoga can be a spiritual practice. But for some of Donohue’s students, it’s nothing beyond a workout. Broga student Larry Lewin, 68, says he’s “a-spiritual,” and that’s exactly who Broga is designed for. Donohue says it’s “accessible to people who would walk away from a room full of Hindu statues and lotus flowers.”

New Broga student Kurt Krueger, 61, says his masculine perspective is what kept him from trying yoga, which he perceived as weird, exotic and foreign. “For an old white guy, it’s hard to get into something generated in a different country and culture, with no specific connection to me. It’s unfamiliar,” says Krueger of yoga’s lineage.

When a gym staffer suggested he try the Broga class, Krueger said “Yoga? Come on, man…” But he says his generation’s oldschool male perspective is changing, and Broga is helping shift it for him. Unlike the team sports he grew up playing, Broga isn’t achievement-oriented. He can go at his own pace.

Other students are finding Broga to be a game-changer. Lewin says he’s tried yoga classes at different stages of his life, but they never “worked” for him. This was partly because he compared his ability to other students’ and tried to copy their poses.

From left to right, Larry Lewin, Jesse Springer and Quinn Aikens during a weekly Broga class at In Shape Athletic Club. Despite the name, the class draws a mix of men and women.

Standing in the front of the room on a small platform, Jess Donohue, 47, leads her weekly mid-day Broga class at local gym In Shape Athletic Club.

JESS DONOHUE

“I don’t know what I’m doing so I make the classic mistake of looking at people near me who are much more flexible, and end up pulling a muscle and thinking I’m never going to do yoga again,” Lewin says of his past experiences.

Now, he says he walks out of Broga class feeling proud. “I did it again. I’m getting stronger.” These are Lewin’s mantras for his practice today.

Another student, Jesse Springer, 49, says Broga class makes him feel like he accomplished something. “Jess is somehow able to really challenge us to push hard, but at the same time give us permission to accept where we are. I don’t know how she does that, but it’s pretty cool,” he says.

And Donohue says her students get the same physical and mental benefits from coming to class, whether they think they’re exercising or engaging in spiritual practice.

“You go in thinking, ‘I just want a good workout,’ but you get the yoga anyway,” Donohue says.

Sidoti’s biggest critics have been the people most deeply involved in yoga, who feel Broga is disrespectful to yoga’s tradition and lineage. Though yoga teaches acceptance, Sidoti says “they’re the most judgmental and harsh.” He stopped listening to critics early on, choosing to focus on Broga’s mission of accessibility.

Sidoti views Broga as “a big wide open door and on-ramp into the world of yoga.” In his classes, he’s incorporated familiar exercise moves like pushups into a format that also includes contemplative sections at the beginning and end of class.

He offers the variety because “the physical stuff is a little bit easier.” Sidoti says it becomes harder when he asks students to examine their relationship with themselves. “People don’t always necessarily want to do that,” Sidoti says.

But yoga’s core goals are steady breath, a focused mind, and emotional non-attachment to the outcome of your actions—the same goals as meditation, its sister practice. Sidoti’s hope is that people will come for the exercise and stay for the meditation, and over time they’ll be ready to explore the mindful side of yoga more comfortably.

ARRIVING ON THE MAT

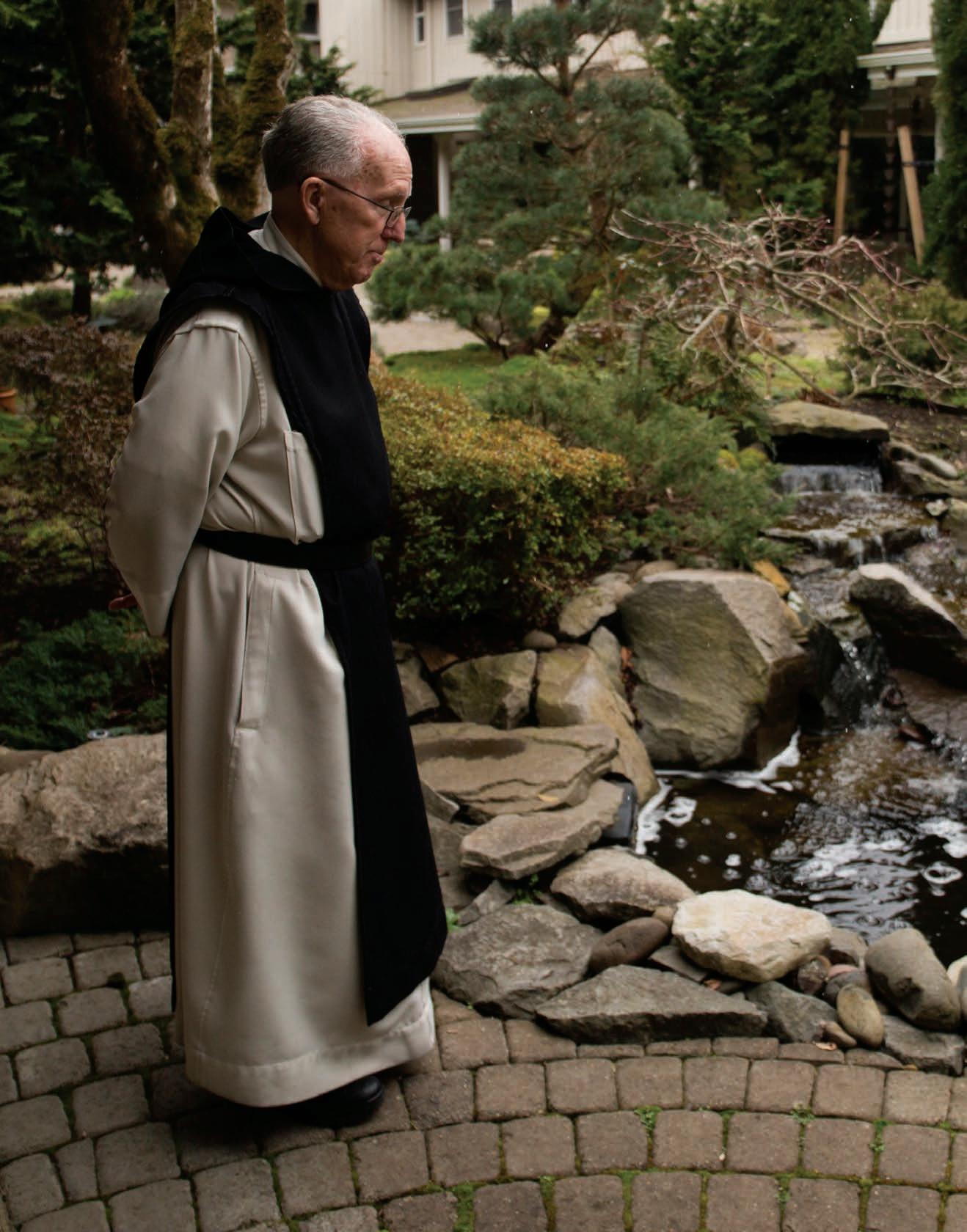

Across the Willamette River in Springfield, studio owner Benjamin Wilkinson is also teaching a hybrid style of yoga he’s calling Common Core. Like the Broga teachers, Wilkinson has experienced the various barriers to getting any student, male or female, onto the mat.

He says the intersection between Broga and his brand is that both try to “take away those standard barriers to entry that have plagued men and just humans especially, in approaching mindful-oriented fitness-based classes.” His goal is to figure out what’s holding back each potential student.

In Wilkinson’s experience, a good approach is to offer his students familiar answers to the question “Why am I here?” He allows them to believe a story they’re comfortable with. He offers pop-up classes in non-traditional settings that focus on the functional workout aspect or include a mimosa or beer. Similar to Sidoti, Wilkinson sees this as a “gateway” approach.

His first yoga experience was all about the workout. “Honestly, I liked it because it kicked my ass. That was the first appeal,” Wilkinson says. As a guy now seeking a mindful yoga practice, Wilkinson has had to remind himself that growth can be difficult. Speaking for men, Wilkinson says “as soon as we open that crack of vulnerability in the yoga world, shit’s gonna come up,” referring to suppressed feelings.

“For me, coming out of camel pose crying? That’s not a cool place to be for a guy,” Wilkinson says. Sometimes, extreme stretching such as in camel pose, which is a backbend or “heart opener,” can release deeply held emotions. Tears on the mat can happen—not from pain, but from the release of tension.

Wilkinson acknowledges that despite his barriers, as a man he benefits from privilege.

“I’m very aware of the fact that as a white, male American I’ve been gifted too much. All I can choose to do, in addition to being active socially and politically, is listen, be humble, and be quiet, and be vulnerable.”

On his journey from yoga student to teacher to studio owner, Wilkinson has made peace with some pretenses of yoga he previously rejected. Assimilating into yoga’s culture was part of evolving “as a male who now will call himself a yogi—who, years ago, laughed at that term. I don’t know at what point I checked my concern and just became a yoga person,” he says of his experience.

Ten years ago, you wouldn’t have caught him saying namaste, either. “I said ‘peace.’ Because if I say ‘Namaste,’ I might be cultconverted into something I’ve not agreed to,” says Wilkinson. Namaste is a Sanskrit word collectively uttered at the end of yoga classes, meaning “the light in me honors the light in you.”

Now that he’s accepted some of yoga’s traditions, he’s here to break others. Wilkinson recently opened Common Bond, a “human yoga studio”. By this, he means it’s unpretentious.

“We have cracks and sawdust and a weird ceiling and concrete. It’s not a pristine environment; it’s not a space that you can control. It’s like life,” Wilkinson says of the studio’s “grandpa-chic” aesthetic. He’s got a set of GI Joe army figurines in yoga poses and a row of upcycled gym lockers in the lounge.

His self-declared strengths are “casual, conversational, relational teaching.” This goes against a more formal, one-directional approach in traditional yoga.

Donohue also pushes back against formalities. She won’t say namaste. She explains why: “It’s not my religion, not my language. It feels like I’d be pretending to be something I’m not,” Donohue says.

So how does she end class? “Sometimes I say, ‘May the force be with you.’ And people laugh. That’s another thing too: life is so serious. It doesn’t have to be serious on the mat too. So, if I can throw a little humor in there and have people have a sense of humor about themselves...Hooray.”

BENJAMIN WILKINSON

UO alum Jesse Donohue, 43, periodically yelled out, “Fish sauce!” triggering laughter from the Broga class. Instructor Jess Donohue, his wife, explained that sometimes a tough workout is like fish sauce—it stinks but you just have to grin and bear it.

Del Hawkins relaxes in Savasana, also known as corpse pose, at the end of Broga class. This is typically the final pose in yoga classes and offers a few minutes of relaxation before class ends.