19 minute read

Lockdown locals

FLYING ADVENTURE

The no land-away restriction of being in Tier 3 at the end of 2020 didn’t put off Paul Kiddell, who limited his coffee intake before he took to flying some three-hour ‘extended locals’…

Advertisement

As the country exited the second national lockdown on 2 December 2020, Northumberland found itself in Tier 3. For the leisure pilot, DfT Tier 3 guidance advised limiting flying with family / bubble members only with no land-aways. While on first glance that may appear restrictive, I saw it as an ideal opportunity for some epic locals. I love winter flying and, historically, December provides excellent flying opportunities over the North East coast – as well as the many impressive inland hill ranges from the Pennines to the Cheviots and Scottish Uplands. Of course, we are very lucky to have two hard runways at Eshott, with 550m and 610m resurfaced portions of two of the original three wartime runways which once hosted the Spitfires of 57 Operational Training Unit.

Our Eshott-based 80hp Rotax 912 Evektor EuroStar has a 65 litre tank, so a good five hours at 12L/hr at 100mph. Of course, being a gentleman of ‘a certain age’ (56), I have other considerations, but I find by limiting my coffee intake that I can manage three hours away from the little boys’ room… comfortably. During December I flew 17 hours on six great extended locals. Here are just two…

Saturday 5 December – Kielder, Spadeadam and North Pennines

On Saturday 5 December, west looked best, with heavy showers forecast for the east coast, so I set off from Eshott at 0930 sharp. Above Rothbury, both of Nelly’s Moss Lakes appeared to be frozen solid.

The lakes were built by Victorian industrialist and arms manufacturer, Lord William Armstrong, to power the beautiful Cragside House, the first in the world to be lit by hydro-electric power. The house is now operated by the National Trust and is definitely worth a visit.

Also on the moors above Rothbury are some of the finest surviving examples of WWI training trenches. In 1915, Northumberland Fusiliers came to Rothbury to train for the battlefields of France and dug a series of trench systems, which show up really well in the low winter sun. The Fusiliers went on to fight in the 1916 Somme offensive, so seeing the trenches is a sobering reminder of those brave young men.

Leaving Rothbury takes me low over the craggy Simonside Hills, which rise to 1447ft at the wonderfully named Tosson Hill. Flying low in the vicinity of hills and mountains requires caution as well as a decent working knowledge of the significant hazards posed, especially by winds aloft.

But today is very calm up to 3,000ft, which makes for a wonderful day to be out playing in the hills at low level. The Eurostar is a great platform for such, with exceptional visibility and great performance, while flying at a sedate 95mph means plenty of time for decision making.

Operating at around 500ft AGL (within the bounds of rule five, either laterally and vertically) isn’t for everyone (or every type), but I feel very comfortable, especially in areas I know well. Having said that, when operating in remote areas I do ensure that I have suitable clothing and a PLB as I’m regularly out of line-of-sight of any ATC unit or D&D. In Rotax we trust!

Continuing south-west, I route around D512B, the Otterburn Range, which is the oldest and largest live firing range in the UK. This is one to avoid as it accommodates the largest weapons in the British Army such as the AS-90 155mm self-propelled gun which, on a quiet night, we can hear firing from our house some 25 miles away. It is active 24/7, 365 days a year, extending up to 18,000ft (ocnl 25,000ft by Notam), and unfortunately, there is no Danger Area Crossing Service (DACS) available.

Patchy fog over Hadrian’s Wall

RAF Spadeadam dummy airfield with Cold War jets, former East German Sukhoi SU-22 and French Air Force Mystere IVs

WWI training trenches at Rothbury

Rothbury

Blue Streak missile test pads at Spadeadam, which was founded in the 1950s

Approaching Rookhope

Next up is Kielder Water, which is the UK’s largest capacity man-made reservoir (Rutland is larger by area) and was completed in 1981, consuming a number of farms and a school in the process. The water, with some 27.5 miles of shoreline, is surrounded by the 250 square miles of the largest working forest in England. Remote Kielder also boasts the largest area of dark sky in Europe and hosts an observatory which is a popular tourist destination.

Encroaching Kielder to the south is another expansive range complex, D510 which contains RAF Spadeadam, the RAF’s Electronic Warfare Tactics Range (EWTR). Here UK and NATO allies come to learn the ‘dark art’ of electronic warfare and how to counter a variety of missile and radar guided anti-aircraft artillery threats.

While the EWTR D510A and D510B are generally only active on weekdays, a small enclave D510C is often active at weekends. D510C is used by civilian company DNV GL to test the effects of explosions by blowing stuff up, often in spectacular style! This informs improvements in safety from the offshore industry to military applications.

Fortunately, today all areas are Notamed inactive, which means I am able to fully explore. Spadeadam was founded in the 1950s as the Spadeadam Rocket Establishment to test the UK’s Blue Streak Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile.

Improvements in Soviet Air Defences led to concern that the RAF V bomber force wouldn’t get through, and so Blue Streak was designed to deliver a one megaton nuclear warhead to Moscow and beyond. Two huge missile stands were built at Spadeadam’s Greymare Hill, and although the missile programme was cancelled in 1960, the structures still exist and, as I circle above, are a most impressive sight.

A few miles to the east of the missile test stands is a dummy target airfield that houses an eclectic range of Cold War jets. Former Belgian Air Force Lockheed T-33s, French Mystere IVs and a solitary former East German Sukhoi SU-22 Fitter. Needless to say, I destroyed them all in an imagined strafing attack before continuing south to Hadrian’s Wall…

Hadrian’s Wall marks the southern boundary of the Spadeadam complex and runs some 73 miles from Wallsend in Newcastle to the Solway Firth. What strikes you from the air is the sheer scale of this feat of Roman engineering, and I feel that many of the forts, such as Housesteads, are best appreciated from above.

I fly over scenic Sycamore Gap, a dip in the wall which funnily enough features a lone sycamore tree, and is known for appearing in Kevin Costner’s 1991 film Robin Hood, Prince of Thieves. In 1983 the tree narrowly escaped when a Jetranger crashed about 30m away while filming it. Fortunately, the pilot and film crew escaped without injury as did TV presenter Alan Titchmarsh on the ground who managed to jump clear as the spinning G-BAML crashed just yards away.

But no such drama today as I pass over the Tyne Valley and climb up into the North Pennines. Above 1,000ft there has been a good snowfall, and with calm winds, I wander low above many picturesque former mining villages such as Rookhope and Allenheads, which even has a ski-lift. Pushing further up onto the remote hilltop moorland devoid of people, vehicles or cables, I indulge in some great flying, playing with my shadow on the deep snow – exceptional fun! I circle Derwent Reservoir (not to be confused with Derwent Valley in the Peak District where the Dambusters trained), which supplies water to the Tyne and Wear metropolitan area.

Heading west, I fly along the ridge containing the three highest mountains in the Pennines – Great Dun Fell, Little Dun Fell and Cross Fell, which at 2,930ft is the highest mountain in England outside of the Lake District. Sitting atop Great Dun Fell is the radome housing the NATS long-range surveillance radar of the same name, and at 2,782ft it looks like Ice Station Zebra covered in deep snow. The road to the site is exceptionally popular with cyclists, offering a steep 4.5 mile climb with very little chance of meeting traffic.

Further west across the valley, the Lake District snow-capped peaks shine in the sun, and while I’ve got fuel to make it, I’ve already been out two hours and ‘personal capacity’ is an issue. So I satisfy myself with reducing power and launching myself off the edge of Cross Fell towards the valley floor far below. It’s easy to get to the 146mph VNe in the Eurostar and I’m cautious, settling on a descent of 118mph, VNo – the max structural cruising speed. What a buzz!

I fly briefly north along the valley before again hopping over the hills to pass over the famous Hartside café at 1,904ft. It is a favourite with bikers and coast-to-coast cyclists, although it has recently been operating out of a container since the building burned down in 2018.

IFR (I Follow Roads) in the North Pennines

Uswayford spruce forest, which is a designated red squirrel reserve

Sam Woodgate enjoying his groupowned classic Evans VP-1

Cheviot foothills

Milfield Airfield, home of Borders Gliding Club and important RAF base in the run up to D-Day

The Potts’ family strip at Stanton

The 13th century Ford Castle near the River Tweed

I’d normally give Carlisle Airport a courtesy call but sadly the airfield has been closed to visitors for most of 2020 and the bulk of the staff, including ATC, remain furloughed. So much has happened since January 2020, when we would fly in to park next to Loganair Saab 340s operating new services to Dublin, Belfast and Southend while enjoying the new café, all for a very reasonable £10 landing fee. In July 2020, Loganair announced it had no plans to resume services after the pandemic. It is, of course, a very challenging time for the industry – good luck to all my chums at Carlisle.

The last 30 minutes of my flight home were spent dodging heavy east coast showers which were increasingly encroaching further inland and I finished off my trip by buzzing the Potts’ family strip at Stanton near Morpeth. Stanton is a steep one-way in and one-way out hillside strip with about 100ft difference from the bottom to the top of the runway, so it is great fun. Chester, who flies a taildragger Escapade and is rebuilding a Europa, is outside and gives me a hearty wave.

After a wonderfully diverse and enjoyable 3.2 hour flight I am back at Eshott. One of the airfield operators, Sam Woodgate, is starting his syndicate’s classic Evans VP-1 G-BDUL. What a fun machine and proves that cheap, grassroots flying is available – it’s £500 to join Sam’s six-member group and £45/month and £7/hr dry. It’s great to hear the Volkswagen engine chattering away as Sam gets airborne, a great end to a great day.

Sunday 27 December – Cheviots, Scottish Uplands and Northumberland Coast

Late December saw some good snowfall on higher ground in the Northumberland Cheviots and Scottish Uplands and so I set off in bright sunshine and freezing temperatures to blow away the Christmas cobwebs. Heading for the Cheviots just 15 miles north-west of Eshott, I pass over the RAF Air Defence radar at Brizlee Wood high above Alnwick, before descending to one of the more unusual sights in Northumberland.

On a farm at Battle Bridge is Manners Combines, the largest breaker of combine harvesters for spares in the UK. Nearly 400 colourful machines are organised in four neat rows. From above, the odd red combine is mixed in with the green and yellow ones and I can’t help but want to reorganise them…

The Cheviot Hills are covered in snow and look spectacular. Despite the depth of snow, you can still see the circular outlines of the many Iron Age Hillforts that litter the area. The man-made forests of spruce not only provide a nice contrast with the snow but are also red squirrel reserves and it’s still common to see them in Northumberland.

Once again, the 3,000ft winds are very light so I enjoy a relaxed, low level flight all the way to the trig point on the very flat 2,674ft summit of the Cheviot, which some 380 million years ago was an active volcano. Trig points only started to appear in 1935 when the Ordnance Surveys’ re-triangulation of Britain project began in an effort to improve the standard of UK maps. The project was finally completed in 1962 by which time around 6,500 trig points had been built.

To the east of Cheviot, the Borders Glider Club field at Milfield looks empty and with no sign of activity on Pilot Aware OGN-R and no response on the radio, I fly over for a closer look. RAF Milfield played a really important part in D-Day and beyond, training RAF and USAAF squadrons in ground attack. RAF Spitfires, Hurricanes and rocket-firing Typhoons along with USAAF P-47 Thunderbolts, P-51 Mustangs and P-38 Lightnings would visit to practise strafing, dive bombing and rocket firing on the nearby Goswick Sands (live) firing range which had a huge variety of targets, including over 50 vehicles and tanks and a section of railway. Although the range closed in 1945, so much ordnance had been dropped that the RAF had a permanent bomb disposal presence until 2011, and as recently as 2009 was still discovering live 500lb bombs.

Heading north across the flat plains in an area far away from any sort of controlled airspace, I orbit beautiful Ford Castle before flying over the 1513 Battle of Flodden memorial. Amid many battles between the English and the Scots, Flodden was the bloodiest and claimed the life of James IV of Scotland, the last British Monarch to be killed in battle, and more than 10,000 of his men.

Fortunately, things are much friendlier these days and crossing the Tweed, I enter Scotland at Coldstream, birthplace of the famous Guards Regiment. During these Covid times I can’t land, so I do low fly-bys at a couple of friends’ Border strips – Gary Burn’s 350m strip at Eccles Newton and Ewan Brewis’ large 600m strip at Lempitlaw. While Gary’s strip is predominantly for microlights/STOL types, Ewan’s immaculate grass strip hosts many SEP visitors and I once parked next to a Cirrus whose owners were taking their dog to a show in nearby Kelso.

Coldstream, birthplace of the Guards, on the River Tweed

The Border area is full of historic memorials and curiosities. At Ancrum, I orbit the 150ft high Waterloo Monument which was completed in 1824 after the first collapsed. Nearby, there is the bizarre sight of a huge domed mausoleum in the middle of nowhere. It is the final resting place of a certain General Thomas Monteath Douglas who, for 40 years in the early 19th century, served in the Bengal Lancers, clearing the Khyber Pass and capturing Kabul. Of course, it all turned into a bit of a drama and on his return, the General, influenced by his time in India, had a mausoleum built where he was laid to rest in 1864. Having served with the RAF in Afghanistan, I was pleased to give him a dip of the wing during a fly-by. As an aside, you can sign keys out to both monuments from Lothian Estates.

Continuing north, the frosty plains give way to the snow-covered Scottish Upland hills. The attractive triple-peak Eildon Hill at Melrose once housed a Roman Army signal station which used fire and smoke to warn, I suppose, of the Scottish hordes heading south…

Entering the Upland Hills at Galashiels in smooth air, I fly over the frozen hills for 20 miles or so circling around Megget Reservoir before returning south. I have good comms with the ever-friendly Scottish Information, which always provides great flight following and is a real comfort when operating in remote areas.

For the last part of my flight in this winter wonderland, I inform Scottish that I’ll be going low level down in the valley floor and will lose comms before descending down to follow the River Ettrick.

This really is a lovely run and I follow the winding river passing farms and the historic 1535 Aikwood Tower, a Peel tower, that was restored by the former Liberal Party leader David Steele in the early 1990s as the family home. Peel towers are small fortified tower houses and are very common in the Northumberland and the Scottish borders due to the extensive Anglo-Scottish wars as well as the activities of the Border Reivers, bandits from both sides of the border who would pillage local communities. Our 11th century village church in Longhoughton has a Peel tower that was actively used as a defended refuge for villagers for some five centuries.

I finally pop out of the Upland hills at Selkirk adjacent to the incredibly scenic 300-year-old Bowhill House. Comms re-established with Scottish, I pass the two huge television and radio masts east of Selkirk which are both over 1,800ft amsl (nearly 800ft agl) before picking up the River Tweed at St Boswells.

For the next 30 miles I follow the scenic Tweed all the way to the sea at Berwick. It’s a delightful journey, full of history, with castles in various states of repair, historic towns like Kelso, Coldstream and Norham, and grand country houses. Of all the interesting bridges, my favourite is the Union Chain Bridge between Horncliffe in England and Fishwick in Scotland. When opened in 1820 it was the longest wrought iron suspension bridge in the world with a span of 449ft. Despite the pandemic, a £10m restoration project is well underway and the bridge will reopen to traffic in 2022.

General Thomas Monteath Douglas mausoleum near Ancrum

Early 18th century Floors Castle at Kelso

A wintry Old Bewick Iron Age double Hillfort

Berwick bridges

Arriving at Berwick, there is a further treat for any bridge aficionados, with three wonderful bridges spanning the Tweed just before it drains into the North Sea – the Old Bridge built from sandstone dates back to 1620, the single-span 1925 Royal Tweed Bridge and the magnificent 1850 Royal Border Bridge, a 28-arch viaduct designed by Robert Stephenson that carries the East Coast mainline. During the Anglo-Scottish wars, Berwick changed hands many times but the border is now 2.5 miles north of the town at Marshall Meadows, England’s most northerly village. Due to the south-west/north-east nature of the border, here we are as far north as the southern part of Glasgow and further north than Bute airstrip.

I exit Berwick over the Elizabethan town walls and head south down the coast. Huge CBs and heavy showers are visible offshore, as I do a 500ft clearing pass of the aforementioned former range at Goswick Sands. Once I’ve checked the remote sands for walkers, horse riders and importantly, flocks of migratory birds, I descend to 10ft or so and enjoy an exciting pass along the shoreline before climbing in good time back to 500ft to pass over Holy Island and its tidal causeway. The water is calm and acts like a huge mirror for the CBs offshore… marvellous!

The imposing Bamburgh Castle is my favourite of the 75 castles in Northumberland. Still owned by the Armstrong family, Bamburgh saw many bloody sieges and also has an excellent aviation archaeology display. The display contains a lot of artefacts and engines of many aircraft that crashed on the Cheviot Hills as well as Luftwaffe aircraft which were shot down in WWII.

On 15 August 1940, the Battle of Britain arrived in Northumberland when the Luftwaffe launched a huge daylight raid from bases in Norway and Denmark. Believing the RAF was fully committed in the South, the Messerschmitt Me-110 escort fighters even left behind their rear-gunners to carry additional fuel. Alerted by the Chain Home radar at Ottercops Moss, 11 Spitfires from 72 Sqn Acklington intercepted a force of some 65 Heinkel He-111s and 34 Me-110s off the Farne Islands just east of Bamburgh. As the attackers bravely continued towards their RAF airfield targets, they were relentlessly harried by an increasing number of RAF Hurricanes and Spitfires from Drem, Acklington, Usworth and Catterick. Despite the RAF inflated claims, the Luftwaffe still lost eight He-111 and seven Me-110s in this raid, which was a disaster. Across the UK, the Luftwaffe lost 75 aircraft that day and it became known to them as ‘Black Thursday’. Importantly, the Luftwaffe never again attempted large daylight raids across the North Sea. The raid is portrayed in the Battle of Britain film and you can see the route to Bamburgh marked on a He-111 pilot’s map.

Holy Island reflections

Lempitlaw strip near Kelso

Galashiels

Megget Reservoir Southern Uplands

Budle Bay looking towards Bamburgh, with heavy showers offshore

Bamburgh Castle with the Farne Islands beyond where Sptifires intercepted a force of 100 Luftwaffe aircraft on 15 August 1940

Just south of Bamburgh, on the sandy coast, is Beadnell Bay which also has an interesting aviation link. On 25 August 1913, 24-year-old Harry Hawker set off from Southampton in a Sopwith Seaplane powered by a 100hp six-cylinder, inline, water-cooled engine. Accompanied by Sopwith’s foreman of works, Harry Kauper, they were attempting 1,540mile Daily Mail ‘Circuit of Britain’ challenge spurred on by a £5,000 prize. They were the only one of the four entrants to set off, sadly British Aviation pioneer Sam Cody had been killed testing his floatplane entry at Farnborough just two weeks prior.

After four stops, Hawker arrived at Beadnell at 1930, having covered 495 miles in a day in nine hours and 18 minutes, a world record at the time. Their unscheduled arrival (due to loss of coolant) caused a sensation as many people had never seen an aeroplane. One local lad was recorded as shouting, “Lookee yonder, there’s a muckle gate coming over Point End!”

After a night as guests of Colonel Craster, they again set off and made Oban the following night. On day three, the expedition ended as they crashed on approach to land near Dublin, Hawker was unhurt although Kauper broke his arm. While they did not complete the challenge, the Daily Mail awarded them £1,000 for completing around 1,043 miles of the 1,540-mile course.

Hawker went on to be test pilot for Sopwith and played a key role in the development of the Pup and the Camel. In 1920 he formed the HG Hawker Engineering company with Tommy Sopwith but sadly died soon after, aged just 32, in a Nieuport Goshawk while practising for the 1921 Hendon Air Pageant.

Having been airborne for three hours, my own personal endurance challenge was about over and I returned to nearby Eshott.

Despite all the challenges of 2020, I enjoyed a fabulous flying year, visiting 83 different fields with great friends in 145 hours aloft. But with an aeroplane and a bit of imagination, you really don’t have to go far to enjoy a brilliant adventure.

Looking beyond the current surge, I’m full of optimism, really looking forward to getting the jab – and see you on the other side…

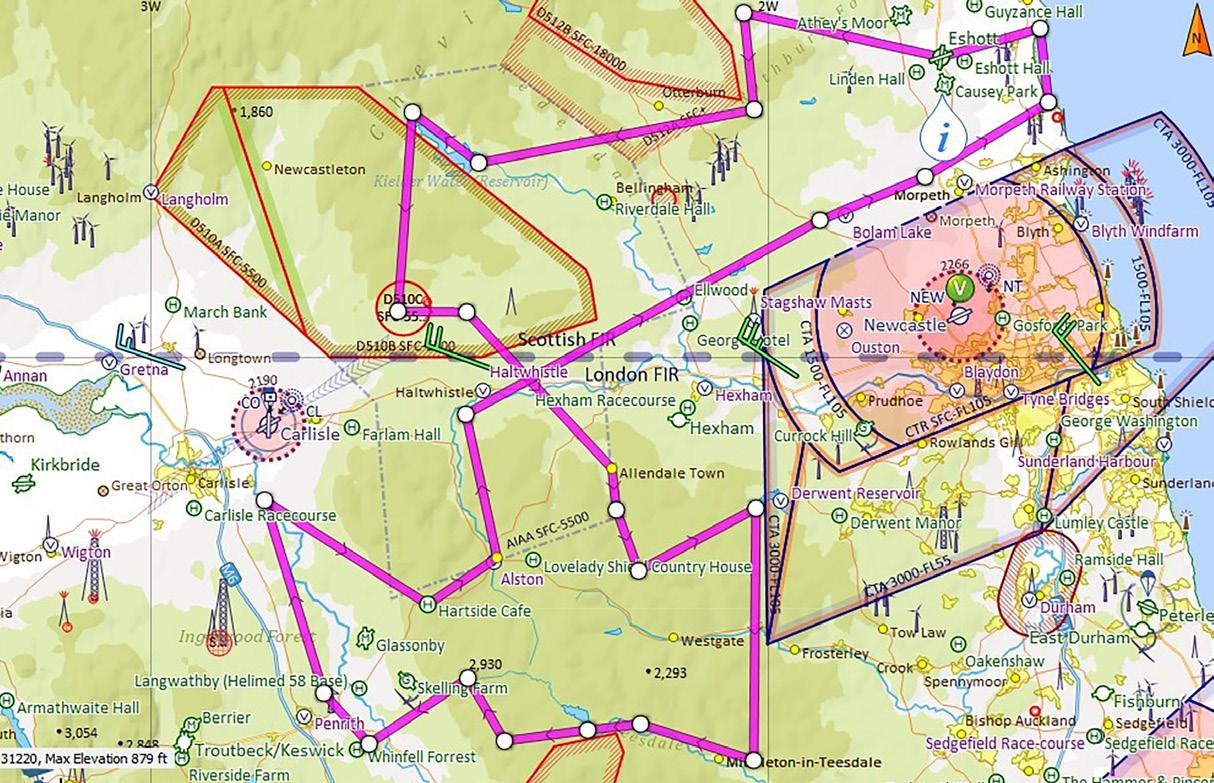

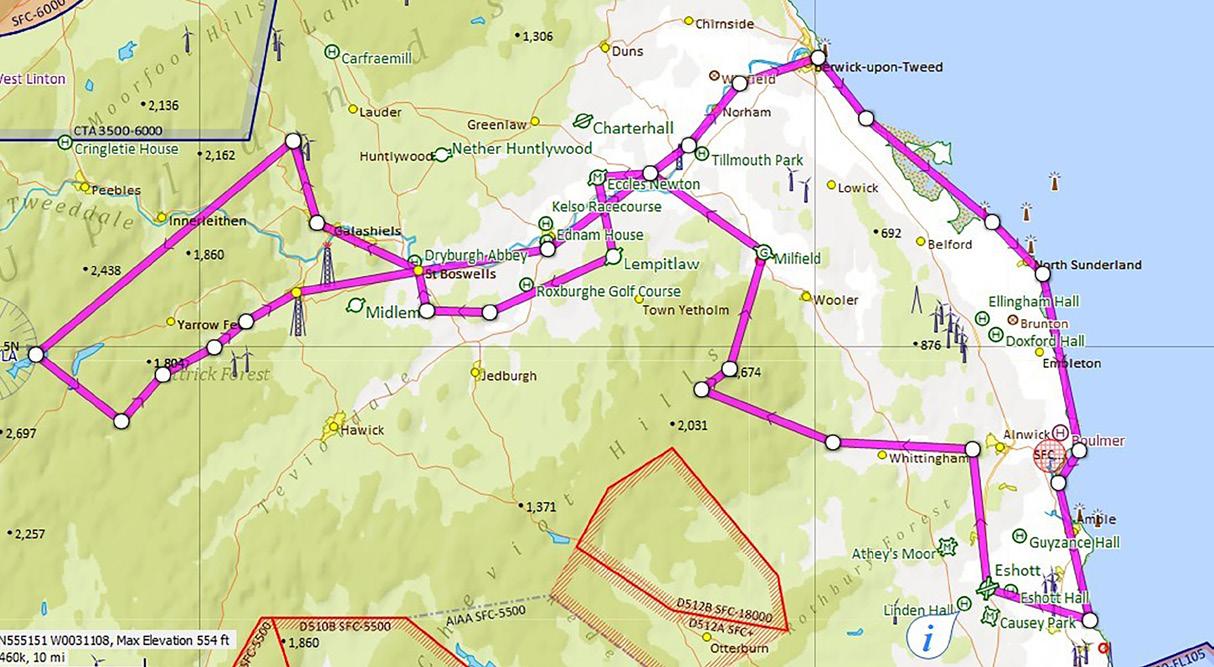

Route Map

Flight 1 Kielder, Spadeadam and North Pennines

Flight 2 Cheviots, Scottish Uplands and Northumberland Coast